Abstract

In Kenya in 1999, an estimated 6.9% of women nationally said they had exchanged sex for money, gifts or favours in the previous year. In 2000 and 2001, in collaboration with sex workers who had formed a network of self-help groups, we conducted an exploratory survey among 475 sex workers in four rural towns and three Nairobi townships, regarding where they worked, the number of clients they had and the risks they were exposed to. Participants were identified by a network of social contacts in the seven centres. Most of the women (88%) worked from bars, hotels, bus stages and discos; 57% lived with a stable partner and almost 90% had dependent children. In the previous month, 17% had been assaulted and 35% raped by clients. Unwanted pregnancy was common; 86% had had at least one abortion. Compared with women in rural towns, township sex workers were younger (median age 22 vs. 26), saw more clients (median 9 vs. 4 per week) and earned more from sex work (up to €63–90 vs. €12 per week). Issues of alternative sources of income, safety for sex workers and the conditions which create the necessity for sex work are vital to address. The question of number of clients and the nature of sex work have obvious implications for HIV/STI prevention policy.

Résumé

Au Kenya en 1999, on estimait que 6,9% des femmes avaient eu des relations sexuelles contre de l'argent, des cadeaux ou des faveurs pendant l'année précédente. En 2000 et 2001, en collaboration avec des prostituées qui avaient formé un réseau de groupes d'auto-assistance, nous avons mené une enquête auprès de 475 prostituées dans quatre villes rurales et trois bidonvilles de Nairobi, afin de déterminer pourquoi elles se prostituaient, le nombre de leurs clients et les risques auxquels elles étaient exposées. Les participantes ont été identifiées par un réseau de contacts sociaux dans les sept centres. La plupart des femmes (88%) travaillaient dans des bars, des hôtels, des gares d'autobus et des discothèques ; 57% vivaient avec un partenaire stable et presque 90% avaient des enfants à charge. Le mois précédant l'enquête, 17% avaient été battues et 35% violées par des clients. Les grossesses non désirées étaient fréquentes ; 86% avaient avorté au moins une fois. Comparées avec les prostituées rurales, celles des bidonvilles étaient plus jeunes (âge médian 22 contre 26), voyaient davantage de clients (valeur médiane 9 contre 4 par semaine) et leur activité rapportait davantage (jusqu'à 63-90€ contre 12€ par semaine). Il est vital d'étudier des questions comme les sources alternatives de revenus, la sécurité des prostituées et les conditions qui rendent la prostitution nécessaire. Le nombre de clients et la nature du travail sexuel ont des conséquences évidentes sur la politique de prévention du VIH/SIDA.

Resumen

En 1999, aproximadamente el 6.9% de las mujeres en Kenia informaron de haber intercambiado sexo por dinero, regalos o favores durante el año anterior. En 2000 y 2001, en colaboración con trabajadoras sexuales que habı́an formado una red de grupos de autoayuda, realizamos una encuesta exploratoria entre 475 trabajadoras sexuales en cuatro pueblos rurales y tres municipios de Nairobi, respecto al lugar donde trabajaban, el número de clientes que tenı́an y los riesgos a los que se exponı́an. Las participantes fueron seleccionadas por una red de contactos sociales en los siete centros. La mayorı́a de las mujeres (el 88%) trabajaban en bares, hoteles, estaciones de autobús y discotecas; el 57% vivı́a con una pareja estable y casi un 90% tenı́a hijos dependientes. En el mes anterior, el 17% habı́a sido asaltada y el 35% violada por sus clientes. El embarazo no deseado era común; el 86% habı́a tenido por lo menos un aborto. Comparadas con las mujeres en los pueblos rurales, las trabajadoras sexuales de los municipios eran más jóvenes (edad promedio de 22 frente a 26), veı́an más clientes (promedio de 9 frente a 4 por semana) y ganaban más dinero realizando trabajo sexual (hasta €63–90 frente a €12 por semana). Es vital abordar las cuestiones relacionadas con otras fuentes de ingreso, la seguridad de las trabajadoras sexuales y las condiciones que crean la necesidad de realizar trabajo sexual. La interrogante del número de clientes y la naturaleza del trabajo sexual tienen obvias implicaciones para las polı́ticas de prevención de las ITS/VIH.

Women who engage in commercial sex in sub-Saharan Africa are at high personal risk of physical and sexual violence, unwanted pregnancy, and sexually transmitted infections (STIs). In Kenya, where an estimated 6.9% of women nationally said they had exchanged sex for money, gifts or favours over the previous year, according to the 1999 Demographic and Health Survey,Citation1 there is a need for better understanding of the extent of these problems. Kenya is experiencing a serious epidemic of sexually transmitted infections, including HIV, and unprotected heterosexual sex is the most common method of spread of HIV.Citation2 Women involved in sex work are seen as both the most vulnerable group to HIV infection and the most effective partners in the fight against HIV. Community interventions to prevent sexually transmitted infections in sex workers have been taking place in Kenya in small groups since 1982.Citation3 Condom use 100% of the time, treatment of sexually transmitted infections and reduction in the number of partners are all recommended to slow the spread of HIV.

Policy on HIV prevention has long made sex workers a priority target, based on estimates of high numbers of client partners combined with unprotected sex.Citation4 Some peer groups in Kenya have been effective at raising the prevalence of condom use to 80% within targeted intervention groups.Citation5 However, despite the evident effectiveness of peer interventions with sex workers, such programmes have not been scaled up to national level and most Kenyan sex workers are still at grave risk for the virus.

Sex workers are frequently stigmatised in ways that predispose them to economically marginal living conditions and that make continued sex work necessary in order to maintain household income. When they have no alternative source of income, they are less likely to refuse clients who obviously have a sexually transmitted infection or insist on condom use.

In Kenya, our experience in supporting women's self-help and income generation groups since 1987 revealed that such groups often tended to exclude sex workers. ICROSS has therefore helped sex workers to set up and register self-help groups aimed at generating alternative sources of income. These programmes have ranged from the small-scale manufacture of clothing and tourist souvenirs to street photography. In collaboration with the women in these self-help groups, from June 2000 to March 2001 we conducted an exploratory survey of sex workers in seven areas to ascertain the nature of sex work and risks they were exposed to, to gain a better understanding of the characteristics and risk of abuse and sexually transmitted infections that the women encountered. The impetus to conduct this survey came from the women themselves and they were actively involved as interviewers.

Methodology and participants

Of the seven study areas in which ICROSS had projects for sex workers, four areas–Bondo, Kiisi, Migori and Siaya–are provincial towns with relatively stable and settled, ethnically homogeneous populations. The remaining three–Dagoretti Market, Ngando and Ngong Town–are township areas on the outskirts of Nairobi, whose populations are more mobile, ethnically mixed and economically deprived than those in the provincial towns. Interviewers were recruited from among women sex workers themselves. All had previous experience of survey interviewing through participation in other ICROSS programme planning and evaluation surveys. They were chosen on the basis of their personal knowledge of sex workers in the study areas, in order to maximise the survey coverage and response rate. The interviewers helped to draft the questionnaire, advised on the suitability and acceptability of questions and on appropriate response categories. They also translated the questions into the different languages in which interviews took place. Translations were cross-checked by having a second person translate the questionnaire back into English.

There were two interviewers in each area except in Dagoretti, where there were three. Interviewers were responsible for explaining the purpose of the survey to potential respondents and arranging a suitable interview time. Most interviews were conducted in the participant's home; all were conducted in privacy. Respondents were informed that their participation was anonymous and voluntary. In the provincial towns, all but four sex workers were Luo-speaking and the four were Luyhia speakers, while in the township areas interviews were carried out in Sheng (a Kenyan dialect of Kiswahili), Kikuyu, Kamba and Somali.

Potentially eligible participants were identified using peer networks. Sex workers were defined as women currently exchanging sexual services for money. Women were eligible to participate in the study if they were aged over 15 and had had at least one client in the week prior to interview. The age of 15 was used because the legal situation regarding interviewing under-aged sex workers was not clear, and might have been used as a pretext to arrest the interviewers. As it happened, although no charges were brought, two interviewers in Nairobi were arrested and imprisoned for the duration of the study. Women were excluded from the study if they had not been active in sex work for part of the week prior to interview, to remove this as a source of bias in estimating client numbers. For quality control, 50 interviews were repeated by a second interviewer within 48 hours. None of the repeat interviews revealed any important discrepancies.

Findings

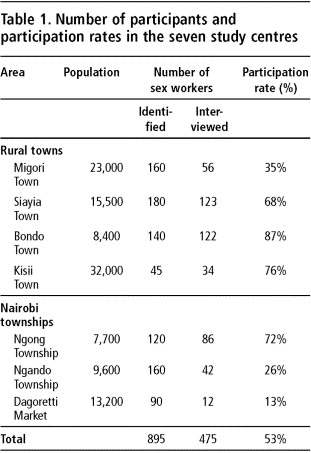

A total of 475 women were interviewed, of whom 336 were in rural population centres and 139 in townships . A further 14 interviews were abandoned, in 12 cases because the woman decided not to participate and in two cases because the interviewer realised that the respondent was a minor. The women who conducted the surveys were asked to count the number of sex workers known to them or to other women who could potentially have taken part in the study. While these estimates fall well short of being a census of sex workers, they give some indication of the study participation rates in the different centres. The smallest social network of sex workers was in Kisii Town, where the self-help group had been formed less than three months prior to the date of the survey. The lowest participation rates were in Migori Town, Ngando Township and Dagoretti Market. The two latter townships are economically very deprived, and social networks among sex workers would be weaker than in other centres. One provincial town, Migori, also had a low response rate, probably a reflection of the intolerance for sex work which characterises a number of the religions of the area.

Most of the women interviewed (88%) worked from bars, hotels, bus stages and discos, and tended to move back and forth between these venues (data not shown). Such women generally know each other and have a regular “territory”. Only 27 worked in brothels, which are usually run by a group of women as a business. Nineteen worked as “loners” outside the networks which operate in hotels and bars, and 13 worked exclusively with tourist clients.

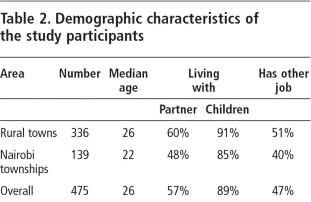

More than half (57%) lived with a stable partner and almost 90% had dependent children. Sex workers in the Nairobi townships were significantly younger ; half were aged 22 or under, while half the women in the rural towns were aged 26 or younger (p<0.0001, Wilcoxon rank sum test). Nairobi township women were also less likely to be living with a stable partner. However, this difference was not statistically significant when corrected for age. There was no significant difference between township and rural town women in respect of the numbers with children. Overall, roughly half the women had at least one other job as a source of income in the week of the survey. We examined differences between the women who worked in bars, hotels, bus stages and discos and those who worked in other settings; no significant differences emerged in any of the variables; however, the small numbers available give these comparisons low statistical power.

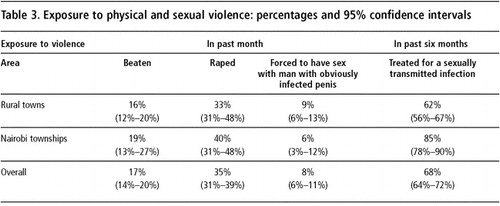

There was a significant incidence of both physical and sexual violence at the hands of clients and other men encountered in the course of sex work , with 35% of the women reporting rape, that is, being forced to have sex unpaid with a client because of threat of or actual use of physical violence in the previous month, and 17% reporting being physically assaulted by a client.

Unwanted pregnancy and abortion were common, with 86.1% of the women reporting at least one lifetime abortion (95% CI 83.0% to 89.2%), and 50% reporting two or more (95% CI 45.4% 54.4%). There was no difference between township and rural town sex workers in the prevalence of abortion.

In addition, 8% of the women reported that during the previous month they had at least one client who had an obviously infected penis but with whom they were nevertheless obliged to have sex through economic necessity and/or fear of physical violence if they objected. Two-thirds of the women had been treated for a sexually transmitted infections in the previous six months. Township women had a higher risk of reporting treatment for a sexually transmitted infections (risk ratio 1.4, 95% CI 1.2 to 1.5). None of the indices of sexual violence differed significantly between township and rural women.

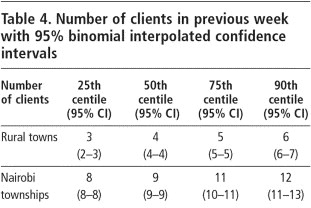

The median number of clients in the previous week was nine among the Nairobi township women and four among the rural town women . A quarter of township women had eight clients a week or fewer, and three-quarters had 11 or fewer. Only 10% of township women had more than 12 clients in the previous week (the highest number of clients reported in the previous week was 19). Rural town women reported fewer clients, with three-quarters reporting five or fewer in the previous week and only 10% reporting more than six clients (with the highest number of clients reported in the previous week being nine). The difference in client levels between rural town and Nairobi township women is highly significant (p<0.0001, Wilcoxon rank sum test).

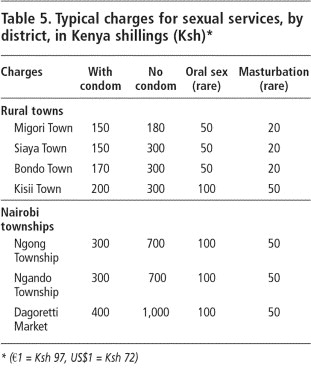

In order to assess the economic significance of sex work, we established the current costs of commercial sex using local informants (, data collected January 2004).

The typical charges for sexual services did not vary significantly within districts. Charges were higher for all forms of sex in the Nairobi townships, frequently by a factor of two. Translated into economic terms, the difference between sex work in the townships and rural towns is thereby accentuated. With the median number of clients, a woman in a rural town would earn up to Ksh 1,200 (just over €12) in a week, while a woman in a township would earn between Ksh 6,300 and Ksh 9,000 (€65–93).

Discussion

Sex workers in Kenya have been doubly disadvantaged in the recent past. Not only do they run serious risks of physical and sexual violence, but they have also been stigmatised as carrying the main responsibility for spreading HIV. This targeting received a powerful imprimatur with the publication of the World Bank report Confronting AIDS. Moses and others had estimated that raising condom use in 500 sex workers to 80% would avert 10,000 HIV infections per year, whereas a similar level of condom use among 500 low-income men would avert only 88 infections.Citation4 These calculations were based on a rate of four paying partners per day, a figure derived from the Nairobi Prostitutes Study, a long-term study of urban sex workers in Nairobi. This, combined with the characterisation of prostitutes as “a major reservoir of sexually transmitted disease”,Citation6 has resulted in prostitution being seen as the cause of disease rather than the consequence of economic marginalisation. Inevitably, it has also helped to draw attention away from male sexual behaviour, and put the onus of disease prevention on the women.

While much of the literature has focused on the potential of sex workers to infect others with HIV, little has been written about the need to protect sex workers from abuse and disease. The intense focus on sex workers as “disease carriers” is readily visible in the literature. In a PubMed search we retrieved 25 citations from 2001 and 2002 that contained the words “sex worker” or “prostitute” in the title which described empirical research in an African setting. Of these, 24 were concerned with sexually transmitted infections. The only apparent exception, which examined the use of health services by sex workers, was in fact about the prevalence of sexually transmitted infections and patterns of condom use.Citation7

Before discussing our findings, we should draw attention to the methods used both to identify respondents and to collect data in the present study. By their very nature, sex workers are resistant to random or other representative sampling methods. By using peer networks to identify potential participants, we aimed to increase representativeness. Nonetheless, this may have biased our findings. It is likely that the data under-represent women who see few clients or who spend only a limited proportion of the year engaged in sex work. The data also, in all likelihood, over-represent women who work in settings such as hostels and bars, where several sex workers tend to be active. Taken together, these factors may bias the number of clients upwards in our sample. Any effect on exposure to sexual violence is not clear.

The use of peer interviewers was done to increase a sense of ownership of the research by both interviewers and participants, and to ensure that the interviews were carried out in as non-judgemental a way as possible, minimising social acceptability bias. Interviewers were also familiar with sex work and consequently less likely to accept implausible answers without attempting to get clarification. Finally, sex workers are often non-indigenous, and so interviews may need to be translated into the languages of the participants. Ensuring that terms and expressions in the interview were those which the women themselves would have used was intended to make the interviews as valid as possible. We believe it provided a wider coverage of the population of sex workers than might otherwise have been possible, and increased the validity of the interview data. However, the results may not be directly comparable to data collected using other sampling and interviewing methods.

One striking feature of our findings is client levels, which fall far below those which formed the basis of policy in the World Bank report.Citation5 While high sex client numbers may characterise urban brothels in Nairobi, a very different picture emerges from women working in Nairobi townships and in rural towns. Women in rural towns rarely see even one client per day (90% see six a week or fewer) and even in the townships surveyed, 90% of women see fewer than two clients a day.

Our data are broadly similar to those reported in a small survey also carried out in rural Kenya by GathiqiCitation8 but not subsequently published, both in terms of the demographic characteristics of the women and the typical level of clients. HawkenCitation7 studied women sex workers in Mombasa, Kenya, who supplemented their income with sex work, and found typical client levels of less than three per week. Pickering, in a lengthy study of sex workers in the Gambia, reported average client levels of 9.5 per month.Citation9 In another study, Pickering reported on a cohort of Ugandan sex workers among whom the average level of clients was 15.9 per month.Citation10 The only published study which shows relatively high client levels was one done of sex workers in bars in Harare in 1989, where Wilson et al reported average rates of 10.1 clients per week.Citation11 We have been unable to find any other published reports of sex workers with a client turnover of four per day as found in the Nairobi Prostitutes Study.Citation5 We should underline the fact that the townships in our study are on the outskirts of Nairobi; the furthest, Ngong Town, is hardly 30 minutes from the centre of Nairobi by public transport.

Although the available data are limited, the much lower client turnover reported here and elsewhere suggests that the original rationale for targeting sex workers on the grounds of very high client frequencies, and failing to target others at the same time who are equally at risk, may be flawed. Certainly it would be instructive to recalculate the original World Bank projections using the lower client rates reported, and to examine the consequences for policy.

The reasons for the discrepancy between the reported frequency of clients in our sample and those derived from the Nairobi study require some comment. The Nairobi study is a long-term study of sex workers who have regular contact with the study centre and who have been sex workers over a period of years. By contrast, this cross-sectional study includes many women for whom sex work is only one of their sources of income. Such women, in sub-Saharan Africa, will typically move into and out of sex work, depending on the availability of other sources of income.Citation12, Citation13 The question of whether high numbers of clients or the low numbers found here and in other small studies are more representative of sex workers as a whole remains an important but unanswered question, with obvious implications for HIV/STI prevention policy.

Research into sex work in sub-Saharan Africa has been criticised for applying European and American assumptions about the nature of sex work, and assuming sex workers to be full-time and long-term (see, for example, the South African Law Commission's issue paper on adult prostitutionCitation14). There has been a naive attempt to make a sharp separation between commercial sex and “legitimate” sex rather than acknowledging that there is a continuum between them.Citation15 This is especially important in sub-Saharan Africa, where in township and rural settings sex may be exchanged for commodities as well as money, and where the women involved may not define what they are doing as prostitution.Citation16

The results of this study do not so much describe the conditions of sex work in Kenya as reveal how little has been documented about them. The level of sexual and physical violence against sex workers underlines the need to address safety for sex workers, which is caught up with issues of legality and stigma. Likewise, the economic and social conditions which create the necessity for sex work have been neglected, but are vital to address if women are to have other viable options to support themselves and their children. In the present instance, combining data on frequency of clients and charges for sexual services reveals that the economic significance of sex work is very different in rural towns, where it typically provides only in the region of €12 a week of income, and in townships, where the amount may be €60–90. This would argue that different approaches for creating alternative sources of income are required in the two settings.

It is a healthy sign that the impetus to conduct this survey came from the women themselves. The findings highlight the need to move beyond the stereotype of sex workers simply as “reservoirs of infection”. While sex workers are at risk both of getting HIV/STIs and transmitting them, not least because of low levels of condom use with clients and other partners, they are also young women who are working in an occupation which is physically and psychologically dangerous, and are in this position as a result of economic marginalisation.

It is more than a decade since Carovano called on those involved in HIV and AIDS prevention to abandon an almost exclusive focus on women as either “mothers or whores”.Citation17 There has not been a lot of progress.

Acknowledgements

We gratefully acknowledge the members of the self-help groups who participated in this study, and especially those who helped to draft and carry out the interviews. We are very grateful for the advice and expertise of Dr. Bridgit Stirling of Icross, Canada, in the preparation of the manuscript. The research was supported as an integral part of the self-help group programme by ICROSS Canada, ICROSS Ireland, Elizabeth Taylor AIDS Foundation and Mercury Trust, to whom we are very grateful.

References

- Demographic and Health Survey, Kenya. 1999; National Council for Population and Development, MEASURE: Nairobi.

- National AIDS Control Council. Kenya National HIV/AIDS Strategic Plan 2000–2005. 2000; NACC: Nairobi.

- A Ronald, F Plummer, E Ngugi. The Nairobi STD program. An international partnership. Infectious Disease Clinic of North America. 5: 1991; 337–352.

- World Bank. Confronting AIDS: Public Priorities in a Global Epidemic. 1997; Oxford University Press: Oxford.

- B Stirling. Cost-effectiveness analysis of three HIV prevention interventions in Kenya: a mathematical modelling approach. PhD thesis. 2003; University of Manitoba: Toronto.

- LJ D'Costa, FA Plummer, I Bowmer. Prostitutes are a major reservoir of sexually transmitted diseases in Nairobi, Kenya. Sexually Transmitted Diseases. 12: 1985; 64–67.

- MP Hawken, RD Melis, DT Ngombo. Part time female sex workers in a suburban community in Kenya: a vulnerable hidden population. Sexually Transmitted Infections. 78: 2002; 271–273.

- Gathiqi HW, Bwayo J, Karuga PM, et al. The socio-economic status of prostitutes at a truck drivers' stop and their interaction with male clients. International Conference on AIDS. 6–11 June 1993, Abstract No. PO-D09-3672.

- H Pickering, M Quigley, RJ Hayes. Determinants of condom use in 24,000 prostitute/client contacts in The Gambia. AIDS. 7(8): 1993; 1093–1098.

- H Pickering, M Okongo, B Nnalusiba. Sexual networks in Uganda: casual and commercial sex in a trading town. AIDS Care. 9(2): 1997; 199–207.

- D Wilson, P Chiroro, S Lavelle. Sex worker, client sex behaviour and condom use in Harare, Zimbabwe. AIDS Care. 1: 1989; 269–280.

- J Swart-Kruger, LM Richter. AIDS-related knowledge, attitudes and behaviour among South African street youth: reflections on power, sexuality and the autonomous self. Social Science and Medicine. 45: 1997; 957–966.

- M Gysels, R Pool, B Nnalusiba. Women who sell sex in a Ugandan trading town: life histories, survival strategies and risk. Social Science and Medicine. 54: 2002; 179–192.

- South African Law Commission. Adult prostitution. In: Project 107: Sexual Offences. Issue Paper 19, Chapter 4. Johannesburg: South African Law Commission, 2002.

- L Dirasse. The Commoditization of Female Sexuality: Prostitution and Socio-economic Relations in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. 1991; NYAMS Press: New York.

- T Leggett. The least formal sector: women in sex work. Crime and Conflict. 1998; 13.

- K Carovano. More than mothers and whores: redefining the AIDS prevention needs of women. International Journal of Health Services. 21: 1991; 131–142.