Abstract

This study in rural Tamil Nadu, India, explored the reasons why many married women in India undergo induced abortions rather than use reversible contraception to space or limit births in terms of women's sexual and reproductive rights within marriage, and in the context of gender relations between couples more generally. It is based on in-depth interviews with two generations of ever-married women, some of whom had had abortions and others who had not, from 98 rural hamlets. The respondents were 66 women and 44 of their husbands. Non-consensual sex, sexual violence and women's inability to refuse their husband's sexual demands appeared to underlie the need for abortion in both younger and older women. Many men seemed to believe that sex within marriage was their right, and that women had no say in the matter. The findings raise questions about the presumed association between legal abortion and the enjoyment of reproductive and sexual rights. A large number of women who had abortions in this study were denied their sexual rights but were permitted, even forced, to terminate their pregnancies for reasons unrelated to their right to choose abortion. The study brings home the need for activism to promote women's sexual rights and a campaign against sexual violence in marriage.

Résumé

En Inde, de nombreuses femmes mariées avortent au lieu d'utiliser une contraception réversible pour espacer ou limiter les naissances. Une étude au Tamil Nadu rural a examiné les raisons de ce phénomène du point de vue des droits génésiques des femmes dans le mariage, et plus généralement dans le contexte des relations de couple. Elle est fondée sur des entretiens avec deux générations d'épouses, dont certaines ont avorté et d'autres non, originaires de 98 hameaux ruraux. L'étude a interrogé 66 femmes et 44 de leurs maris. Le recours à l'avortement par les femmes, tous âges confondus, s'expliquait par les rapports sexuels non consensuels, la violence sexuelle et l'incapacité des femmes de refuser les exigences sexuelles de leur mari. Beaucoup d'hommes semblaient penser que les relations sexuelles dans le mariage étaient un dû, et que les femmes n'avaient pas leur mot à dire. Les conclusions remettent en question l'association présumée entre droit à l'avortement et jouissance des droits génésiques. De nombreuses femmes ayant avorté se voyaient refuser leurs droits génésiques, mais on les autorisait–les forçait même–à interrompre leur grossesse pour des raisons sans rapport avec leur droit à l'avortement. L'étude montre qu'il faut militer pour promouvoir les droits génésiques des femmes et faire campagne contre la violence sexuelle dans le mariage.

Resumen

En este estudio, realizado en rural Tamil Nadu, se exploraron los motivos por los que muchas mujeres casadas en la India recurren al aborto en vez de utilizar anticoncepción reversible para espaciar o limitar los partos, con relación a los derechos sexuales y reproductivos de las mujeres dentro del matrimonio y, de manera más general, al contexto de las relaciones de género. El estudio se basa en entrevistas a fondo con dos generaciones de mujeres alguna vez casadas, algunas de las que habı́an tenido abortos y otras que no, provenientes de 98 áreas rurales. Los respondedores fueron 66 mujeres y 44 de sus maridos. Al parecer, el acto sexual sin consenso, la violencia sexual y la incapacidad de la mujer de rechazar las exigencias sexuales de su esposo eran las causas de recurrir al aborto entre las mujeres de cualquier edad. Muchos hombres pensaban que las relaciones sexuales dentro del matrimonio son su derecho, y que las mujeres no tienen opinión al respecto. Los resultados plantearon preguntas respecto a la asociación entre la interrupción legal del embarazo y el goce de los derechos sexuales y reproductivos. A muchas de las mujeres que abortaron se les negaron sus derechos sexuales pero se les permitió, incluso fueron forzadas a, interrumpir sus embarazos por razones no relacionadas con su derecho de tener un aborto. El estudio demuestra la necesidad del activismo para promover los derechos sexuales de las mujeres y una campaña contra la violencia sexual dentro del matrimonio.

Since abortion was legalised in India in 1971, a number of studies have been published on the incidence of abortions within and outside approved medical facilities; on the characteristics of women seeking abortion services; the nature, distribution and quality of abortion services; and on abortion-related morbidity and mortality.Citation1, Citation2 Only a small number of studies have ventured into other areas. Some of these have examined the decision-making process to terminate pregnancy among married women, in regard to spacing births or preventing an additional birth. Citation3 Citation4 Citation5 Citation6 Many of the women in these studies who did not want any more children underwent sterilisation following abortion, while those who had terminated a mistimed pregnancy rarely accepted a reversible method of contraception after the abortion.

One question that has not been asked in the Indian context is why women undergo induced abortions rather than use contraception to space or limit births. The answer may have to do with women's lack of adequate knowledge about the safety of reversible contraceptives, or the limited availability of methods or information through government family planning services, or both. Another could be that they discontinued use of a reversible method due to adverse side effects, became pregnant and then relied on induced abortion for spacing. Or again, they may have been using ineffective methods, or using effective methods incorrectly, leading to contraceptive failure. However, the reasons may in fact have less to do with contraceptive use than is usually supposed. They have not been studied in terms of women's sexual and reproductive rights within marriage.

It could be that induced abortion is not always an indicator of women's exercise of their sexual and reproductive rights, but rather signifies women's lack of those rights. This would certainly be the case where women are not allowed to use contraception or cannot say no to sexual intercourse.

The Rural Women's Social Education Centre (RUWSEC) is a grassroots women's organisation in Tamil Nadu that has been working on women's reproductive health and rights issues since 1981. In the past two decades, a considerable number of women in the communities covered by RUWSEC's activities have continued to use induced abortion for regulating or limiting their number of children, despite significant changes in levels of female education, women's assertiveness and their greater access to information through the media. What is more, the decrease in the number of children desired may even be contributing to a greater demand for abortion services.

Tamil Nadu is among those states in India that has had close to replacement level fertility since the mid-1990s.Citation7 According to estimates based on National Family Health Survey-I data (1992–93), Tamil Nadu had the highest rate of abortions (spontaneous and induced) among Indian states.Citation8 If, as is believed, a large proportion of induced abortions are reported as spontaneous, the induced abortion rate is even higher.Citation9 The widespread use of abortion as a method of birth spacing was also evident from a 1997 study on fertility transition in Tamil Nadu.Citation10

Data from a statewide reproductive health survey in 1998-99 for Chengalpattu district (of which Kanchipuram district is a part) show that 95% of the rural population receive full antenatal coverage, with little variation by caste or level of education. Among rural women, 81% have knowledge of all modern methods of contraception, falling to 74% among women who are non-literate. The high levels of information notwithstanding, at 54.4%, the district ranks tenth among the 23 districts in Tamil Nadu in terms of contraceptive prevalence. Of those using contraception, 49.3% were sterilised (0.3% of whom were men). Only 3.5% of the women were using modern, reversible methods—IUD (2.6%), pills (0.3%) or condoms (0.5%).Citation11

One of RUWSEC's activities is to promote contraceptive choice. The finding that even as recently as 2002 the use of reversible methods of contraception was still below 7% in the area in which RUWSEC works posed a considerable challenge to the organisation. This is despite RUWSEC's workshops giving information on reversible methods of contraception for both women and men, and dissemination of information through printed material. The organisation also distributes condoms in the community and has made a concerted effort to promote condom use among men. Oral pills and intra-uterine devices (IUDs) are also available at RUWSEC's clinic at no cost.

This research was undertaken by RUWSEC in 2002. Its aim was to explore the extent to which induced abortions in rural Tamil Nadu are a result of women's lack of power to control sexual and reproductive decisions within marriage, and of gender power dynamics between couples more generally. In the light of a dramatic decline in fertility levels and widespread social acceptance of contraception in the last two decades, the study also aimed to examine any changes that may have taken place in women's ability to prevent unwanted and mistimed pregnancies.

The long-term goal of the study was to design community-based interventions to prevent unwanted pregnancies, based on a more in-depth understanding of the processes leading to married women's use of abortion to space births. The main research question was: What role do gender power relations play within marital relationships to influence the choice of induced abortion to space births? Has this role changed during the course of a generation in a context of major social, economic and demographic changes?

Study participants and methodology

The study covered 98 hamlets in Kanchipuram district, Tamil Nadu, the project area served by RUWSEC. This was a qualitative study based on in-depth interviews.

Two generations of married couples were invited to participate, in order to identify any changes in the role of gender power relations in the use of induced abortion. The study sample was therefore drawn from two age groups. The older group were ever-married women above 35 years of age who had completed childbearing (either menopausal or having been sterilised) and who had children over 18 years of age; and the husbands of women in this group who consented to their husbands being interviewed. The younger group were ever-married women under 35, who had not yet undergone sterilisation, and the husbands of those who consented to their husbands being interviewed.

Within each group, we selected equal numbers of women who were “ever-users” and “never-users” of abortion, the latter being women who had never had, nor attempted to have, an induced abortion. Since RUWSEC has a fairly comprehensive database on its project villages, it was used to select a systematic, random sample of women who had never reported an abortion to RUWSEC staff during routine surveillance. Because we were aware that some women may not have reported their induced abortions to RUWSEC, the pregnancy history of never-users was checked during the interviews. Those women classified as never-users who reported having had an abortion were reclassified. None of the never-users reported having attempted an abortion unsuccessfully.

Ever-users of abortion identified as such in RUWSEC's database were asked if they were willing to be interviewed by RUWSEC's village health workers, and some consented. The village health workers also suggested names of others who were willing to be interviewed. We had intended to interview 60 women and 40 of their husbands in all. Fewer men than women were included in the sample to allow for the possibility that not all women would agree that their husbands be interviewed; others might not have husbands currently living with them.

The field investigators were senior community health workers of RUWSEC with considerable experience carrying out workshops and training on gender and reproductive health and rights issues within the study area.

Interview guides included questions related to gender power relations within marriage—defined to include the nature of communication between couples. They asked whether the marital relationship was a sharing, friendly one, or one where the husband was the “superior” partner; the extent of women's freedom of movement; women's role in making everyday decisions related to running the household; the extent of freedom women have in deciding whether and when to have sexual relations, the number and spacing of pregnancies and the use of contraception; and the extent of violence or the threat of violence.

For those who had undergone induced abortions, questions were asked about the reasons for choice of abortion, the decision-making process and the abortion experience. Questions were asked not only about the current period of time but also about experiences starting from the time of marriage and leading up to their present situation. Thus, the analysis is not cross-sectional, but covers the reproductive life span of the women interviewed.

Ethical considerations

A number of steps were taken to ensure that the collection and management of information did not inadvertently violate ethical norms. The study team did not ask anyone to identify those who had undergone abortions until the willingness of such persons to participate in the study was ascertained. Informed consent was obtained from all study participants, and participants had the option of withdrawing at any stage. The identity of respondents was protected through the use of codes in place of their names. No person or village was named in the transcripts, so that no person other than the interviewer knew their identity. Data entered into the computer was similarly protected. Moreover, interviewers were assigned to villages other than their own to minimise the possibility of them divulging any names after the completion of the study. The place and time of interviews was fixed in consultation with the interviewee. Most women chose to be interviewed at home, but specified a time for the interview when they were assured of privacy. Lastly, husbands were interviewed only after obtaining the consent of their wives. Women were interviewed at different places and times from their husbands, the women by female investigators and the men by male investigators. Thus, there was no possibility of the information given by one partner being inadvertently communicated to the other.

Characteristics of study participants

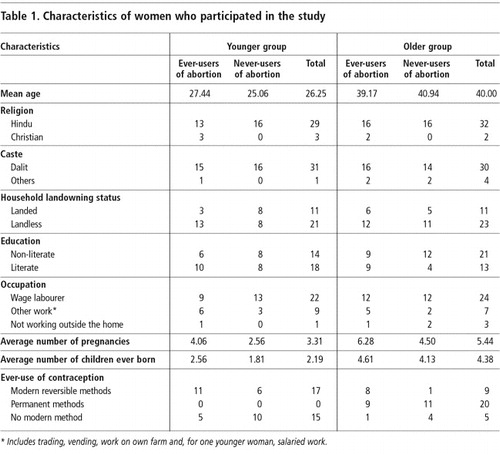

The final sample consisted of 66 women and 44 men; 22 women did not want their husbands to be interviewed. The 66 women included 32 younger women (mean age 26.3) and 34 older women (mean age 40).

All 44 men were husbands of women interviewed; 23 were husbands of ever-users and 21 husbands of never-users of abortion. As regards age, 23 men belonged to the younger age group and 21 to the older age group.

The majority of study participants (93%) were Hindu and belonged to the dalit community. Ninety-four per cent of the women were employed outside their homes, predominantly as agricultural wage labourers (70%). Among the men, 60% worked as day labourers in casual employment; the rest were self-employed as farmers, traders or vendors. The ever-users and never-users of abortion were similar in terms of socio-economic characteristics, except in terms of land-owning status . A significantly greater proportion of abortion users were from landless households compared to never-users of abortion. However, this may not signify a major difference between the two groups since the extent of land owned by most households was very small. Among the older women, a significantly higher proportion of abortion-users were literate compared to never-users of abortion.

Pregnancy and induced abortion history

The comparison of pregnancy and induced abortion history between older and younger women is used as a proxy for changes over time. Although some older women had had abortions during the same time period as the younger women, their numbers were small enough (two of 18) not to affect the overall observations.

On average, the older women had had two more pregnancies and births (average 5.44) than the younger ones (average 3.31). Similarly, the average number of children ever born to the older women was 4.43 and to the younger women 2.19 .

Thirty-four of the 66 women had had one or more induced abortions in their lifetime (ever-users). Of the 34 ever-users, 16 were younger women and 18 were older. Abortions in the older women had happened 5-15 years before, while abortions in the younger women had been 0-7 years before. Nearly two-thirds of the 34 women (22) had had one abortion, eight women had had two abortions, and two had had three and four abortions respectively, making a total of 52 abortions.Footnote* There were no differences between the younger and older women in the distribution of number of abortions per woman.

Three younger women and one older woman had attempted abortion in a previous or subsequent pregnancy to their abortion, but the method used had not been effective and the pregnancy had been carried to term.

The number of weeks of pregnancy when abortion took place were similar in the older and younger age groups. Most of the abortions (36 of 52) were terminated in the first trimester, and a further seven within the first 20 weeks, the legally permitted period. Thirteen women had had abortions at 20–24 weeks (ten women) and three at 24–28 weeks of pregnancy.

About a third of the pregnancies terminated were of lower order—three or below—and one-fourth were of order six and above. There was a shift towards abortion in lower-order pregnancies among younger women. Of the 18 who terminated a pregnancy of order three or below, only three were older women. Of the 13 women who terminated higher order pregnancies, only two were younger women.

Rural medical practitioners, paramedical personnel with no formal training, had performed most of the abortions (40/52). Younger as well as older women frequented these providers, who were all men usually assisted by their wives. Ease of access was an important factor mentioned for choosing these providers. Four of 52 abortions were done by traditional providers, all in older women.

Decision-making on abortion

In 34 of the 52 abortions, the decision to terminate the pregnancy had been taken by the woman concerned. The woman then tried to convince her husband to agree to the abortion. In a little less than half these instances (15/34), although the woman was unable to get her husband's support, she went ahead anyway. Instances of women going for abortion without their husband's consent were far more common among the older women (11/27) than the younger ones (4/25). One reason for this may be that the older women were terminating higher-order pregnancies after repeated attempts to prevent unwanted births, and were desperate enough to go ahead despite opposition from their husbands.

“Already I had five sons and my husband was not co-operating with me… I decided to abort and informed him of my decision. He didn't agree, so I went to my mother's and had the abortion. My parents paid for all the expenses.” (Older woman, ever-user of abortion, no.14)

There may have been relatively less resistance to abortion among younger husbands. This is suggested by the fact that younger women seeking abortions had been accompanied by their husbands to the abortion clinic in most cases (21/25 abortions) compared to older women (8/27 abortions).

In 11 cases, the decision was a joint one and the support of mothers or mothers-in-law was also often sought. In two instances, the pregnancy was terminated on medical advice. Five women were compelled by their husbands and/or in-laws to have an abortion, in some cases because it was believed that the particular pregnancy was inauspicious, and in some because the pregnancy came at a time when the family could not afford for the woman to be “confined”.

“My abortions—I had two— were for economic reasons. When I told him of my pregnancy he said, ‘You have become pregnant in the high season for business, what can we do?’ We run a shop and both of us have to work. So he decided that we should terminate the pregnancy because I would not be able to stand all day in the shop if I was pregnant and that would affect the sales and our income. He asked me to do it and I did it.” (Older woman, ever-user of abortion, no.18)

According to one young man who had to “convince” his wife to have an abortion because of adverse economic circumstances:

“I decided she should abort the pregnancy and she didn't agree… She wept a lot… Then I explained to her the family situation. It took some days to convince her.” (Younger man, ever-user of abortion, no.1)

Reasons given by women for having an abortion

There was a range of reasons given by women for terminating a pregnancy, although the most common ones, predictably, were to limit family size, either because they had achieved their desired family size or for economic reasons, or to lengthen the interval between births. There were differences in the reasons given by older and younger women.

The most common reasons for abortion among the older women were to limit family size (11 abortions) and pregnancy too soon after a previous birth (ten abortions). The six women who had had repeat abortions had terminated their last two, three or four pregnancies to limit family size.

In contrast, the most common reasons given by younger women were economic circumstances and poverty (nine abortions), and not having anyone to support them during or after the pregnancy (six abortions). Except in two instances, these were also the reasons for repeat abortions.

“I aborted three pregnancies, my third, fourth and fifth ones. My family's economic situation was very bad at the time, and I was also not keeping well. He knew about the pregnancies and didn't say anything. I decided. Only I knew the pain and the worries [of having another child].” (Young woman, ever-user of abortion, no.5)

“I aborted my first pregnancy because of my family's economic crisis. We were in a nuclear family and very poor. We took the decision with a heavy heart. There was no way we could manage to have this child because we had no money and no family support.” (Young woman, ever-user of abortion, no.18)

There were only two instances (one younger and one older woman) when abortion was used to avoid the birth of a girl. Neither woman had had a sex-determination test. Both had had several girl children previously and aborted for fear that they might have another daughter. Two women were advised to abort for health reasons. In two cases, pregnancy was terminated because the unborn child was thought to be inauspicious.

“When I became pregnant for the second time, my husband met with an accident and injured his leg. He consulted an astrologer to predict the future and to know the reason for his accident. The astrologer said maybe the reason was that the [unborn] child was inauspicious and suggested that we terminate the pregnancy. My in-laws and husband compelled me. They shouted at me, saying, ‘Is your unknown baby's life worth more than your husband's?’” (Young woman, ever-user of abortion, no.2)

In one instance, a woman who had had two previous caesarean sections had been advised to avoid getting pregnant for the next few years. She did get pregnant, but the couple terminated four consecutive pregnancies because they feared that she would die if she had carried any of them to term.

History of abortion and gender power relations within marriage

To examine whether there were differences between ever-users and never-users of abortion in significant aspects of gender power relations within marriage, the following indicators were used to compare the two groups. Answers were classified as “more equal”, “less equal” or “unequal”:

| • | whether the marriage was by mutual consent or the woman was forced into it; | ||||

| • | whether the woman's expectations from marriage had been fulfilled; | ||||

| • | joint decision-making between the couple, some decisions by the woman, no decisions by the woman; | ||||

| • | extent of the woman's freedom of movement and freedom to act independently; | ||||

| • | absence of non-consensual sex, sexual violence and any other intimate partner violence; and | ||||

| • | husbands' co-operation in pregnancy prevention. | ||||

We asked ever-users of abortion about their perceptions of the role of gender power relations in their exposure to the risk of unwanted pregnancy. We followed this with an analysis of other possible factors that may have contributed to making women abortion ever-users vs. never-users. Overall, there did not seem to be any major differences between abortion ever-users and never-users, either in terms of consent to marriage or satisfaction with marriage.

Women had limited decision-making power within the household, even in the younger age group; men controlled most of the decisions. In fact no clear differences could be discerned between the ever-users and never-users of abortion except that more women in the ever-users vs. never-users group (10/23 vs. 5/21) reported the stereotypical, traditional division of men taking decisions on money matters and women on household matters, such as buying food and perhaps some small extras, like flowers.

As regards freedom of movement, we asked women whether they needed their husband's permission to go out at all or to visit their natal homes, and whether they had to be accompanied. The majority of ever-users of abortion (22/34) needed their husband's permission to go anywhere at all and to go to their natal home. The corresponding figure for non-users of abortion was 15/32.

Visiting the natal home seems to be a particularly sensitive issue. Several women, especially in the younger age group, were only permitted to visit their parents if accompanied by their husbands, were not allowed to go very frequently nor allowed to spend the night. Regular contact with the natal home was viewed by the women as empowering for them, whereas husbands viewed it as a threat to their authority.

Women may have had physical mobility, but only for specifically approved purposes, such as taking a child to a health facility or to go to the market. Nor could they participate in any public activity without their husband's prior permission. In this respect, there was not much difference between the younger and older women.

However, the differences between the two groups were because of differences in the degree of freedom among the older women. In the older age group, the numbers needing permission to go anywhere and to their natal home were 11/18 among ever-users of abortion and 5/16 among never-users. In the younger age group, the corresponding numbers were 11/16 and 10/16 respectively. Among older women who had never had an abortion, the extent of freedom enjoyed clearly increased with age. This pattern did not seem to hold in the group of women who had ever had an abortion, however.

Experience of non-consensual sex, sexual violence and other forms of violence

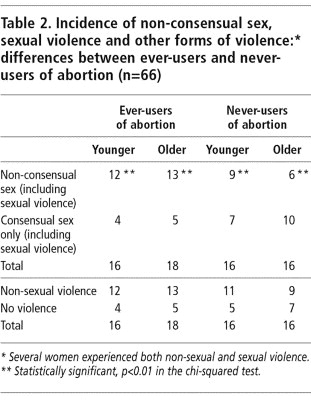

Non-consensual sex was widely prevalent among study participants. Sixty per cent of the women (40/66) stated that they could not refuse if their husbands desired to have sex. Sexual violence was embedded within marriage in a wider context of the use or threat of physical violence to keep women submissive, however. Five women reported intimate partner violence of a non-sexual nature in addition to the 40 who reported sexual violence.

In its mildest form, non-consensual sex made the woman feel humiliated but resigned to her fate. Several women reported that they “would lie like an inanimate object, like a piece of wood, while he went ahead”. Women were also pressured into having sex by their husband's threats to seek sexual pleasure elsewhere. Nine of the 44 men said they had one or more sexual partners besides their wives.

Several of the wives who reported sexual coercion had husbands who reported being considerate and always engaging in consensual sex. Indeed, few men admitted sexual coercion; only nine said they were unable to take “no” for an answer when it came to sexual matters.

“She doesn't object to sex usually, and I have it as I wish. If she objects when she is not well or when she is menstruating, I accept it. But if she objects for other reasons I don't accept it and will have it by compulsion without her desire. I beat her in two types of situations. One is when I am drunk and other is when she says no to sex.” (Young man, ever-user of abortion, no.2)

“Many times my wife expressed reluctance because she was afraid of getting pregnant. I didn't accept her refusal because I was unable to control my feelings. I would force her into sex saying: ‘What is wrong if you conceive again?’ Mostly, I was under the influence of alcohol and that affected my judgement, and I would feel bad in the morning for my harsh behaviour.” (Older man, ever-user of abortion, no.7)

Of all the aspects of gender-power relations examined, non-consensual sex was the single, most important indicator distinguishing the women who had had induced abortions from those who had not . While the presence of violence generally was more common in the ever-user group, the difference was not significant. However, there was a statistically significant difference in the extent of non-consensual sex and sexual violence between the ever-users and never-users of abortion.Footnote*

Table 2 Incidence of non-consensual sex, sexual violence and other forms of violence: Footnote†differences between ever-users and never-users of abortion (n=66)

Six younger and 15 older women considered unwanted pregnancy and abortion to be a direct consequence of non-consensual sex, often accompanied by violence when the women resisted. This was expressed by women as “lack of co-operation” or “carelessness and irresponsible behaviour” on the part of husbands, who “would not leave them alone”.

“When I express reluctance for sex saying that I am worried about getting pregnant, he says, ‘I will take care if it happens.’ If I object strongly he shouts: ‘Are you sleeping with someone else?’ After my first childbirth, he called me for sex within a month. When I objected, he beat me. This is a regular happening in my life.” (Younger woman, ever-user of abortion, no.2)

An older woman who, when we interviewed her, was pregnant for the fifth time, said:

“He works outside the village and comes home once in two or three days. In that situation, I am unable to say no, even if it is during the day. If I object, he shouts: ‘When I am not at home, who comes here?’ He often beats me.” (Older woman, ever-user of abortion, no.17)

Women described numerous unsuccessful attempts to avoid unwanted pregnancy that had ended either in abortions or unwanted births. The men, on the other hand, tended to blame their wives for getting pregnant frequently: “She gets pregnant with a single touch.”

“I have aborted two pregnancies—the second and the fourth. Fear and embarrassment in asking for spacing methods and his compulsion for sex have led to three unwanted pregnancies and two abortions. Even though men are responsible for pregnancy, people generally say it is the woman's fault. They say: ‘Men are good, but women are foolish, emotional and looking for bodily pleasure.’” (Young woman, ever-user of abortion, no.6)

Some women reported that their husbands compelled them to have sex by saying they would pay for the abortion if they got pregnant.

“If I reject his desire to have sex, he says: ‘It is me who will be meeting the expenses. If you conceive you can go for an abortion.’ But he doesn't realise the problems associated with abortions.” (Young woman, ever-user of abortion, no.17)

Contraceptive use

If women are so keen to avoid pregnancy, why do they not use a method of contraception? Comparing contraceptive use among ever-users and never-users of abortion, we found that women who had had an abortion had also tried to use contraception at some time. Eleven of 16 younger women who had had an abortion had used one or more reversible methods of contraception, while six of the 16 never-users of abortion in the same age group had done so . In the older age group (many of whom had subsequently had a sterilisation) eight of 18 ever-users of abortion had used a reversible method of contraception compared to only one of 16 “never-users” of abortion. This trend is corroborated by data from National Family Health Surveys, which show an association between a current, unwanted pregnancy and ever-use of reversible methods of contraception.Citation7, Citation8

The unwanted pregnancies appear to have resulted not only from non-use of reversible methods but also from an inability to use reversible methods consistently, despite the women trying to do so. The most commonly used reversible method was condoms. The men discontinued or used them irregularly for reasons such as non-availability of regular supplies, interference with sexual satisfaction and cost. Reasons for discontinuing the pill and IUD were usually related to side effects. Husbands' opposition to the use of a method of contraception was more common among the older women, although some of the younger women also mentioned it.

Another important difference between ever-users and never-users of abortion was in the average number of pregnancies. The average number of pregnancies among ever-users of abortion was 5.23 (4.06 among younger and 6.28 among older women) while the average number of pregnancies among never-users of abortion was only 3.53 (2.56 among younger and 4.5 among older groups respectively).

Association between non-consensual sex and abortion

How can these apparently contradictory findings be reconciled, that never-users of abortion are less exposed to pregnancy than ever-users, despite being less likely to use a modern reversible method of contraception? The answer appears to lie in the dependence of many women in this study population on abstinence rather than on modern contraception for spacing births, in the interval between the last desired birth and sterilisation, or to avoid future births when sterilisation is contra-indicated. Women who had the co-operation of their husbands in avoiding sex succeeded in preventing unwanted or mistimed pregnancies.

Women who experienced non-consensual sex tried to avoid unwanted pregnancies by using modern reversible methods. When they experienced difficulties in using reversible methods and discontinued use, many were exposed to pregnancy. For women in this group who were contra-indicated for sterilisation, repeat abortions became the only means of limiting family size.

“My body is not suitable for the operation and so I fear getting pregnant. I want to avoid sex. It is good if he leaves me free.” (Young woman, ever-user, no.6)

Many women held their husband's non-cooperation in matters related to sex and contraception to be directly responsible for their abortions and expressed anger towards them.

“He alone is responsible for the abortion, because first he prevented me from having the operation and then he beat me when I was reluctant to have sex. So again it led to an unwanted pregnancy and abortion.” (Older woman, ever-user of abortion, no.2)

“I am pregnant now. I had decided to abort this one also, whether I live or not. But he and my father convinced me to have this child and then have the operation. [After the previous abortion] the doctors did not say anything about preventive methods [contraceptives]. When I asked my husband to find out whether there is anything to avoid getting pregnant, he said: ‘Am I having sex with a prostitute that I have to ask about preventing pregnancy?’” (Young woman, ever-user of abortion, no.6)

Conclusions

Non-consensual sex and sexual violence appear to underlie the need for abortions among many of the women in this study, both younger and older. Although they are well aware of their sexual rights and believe that men ought to take responsibility for preventing pregnancy, the reality the women had to contend with was going through one pregnancy after another, terminating them when they could and carrying them to term when not.

There are differences between the younger and older couples who had used abortion. Older women often had to make the decision by themselves; many had little support from their husbands and had to get the help of their mothers, sisters and neighbours. They also had to seek abortion from places that were affordable, including traditional abortion providers. The decision to have an abortion was more often supported by the husbands of the younger women, who accompanied them to the abortion clinic and paid for the services. This is despite the fact that the pregnancy might well have been the consequence of sexual coercion on the husband's part.

Some women's reports indicate that men may be taking abortion very lightly–as something they can pay for and be done with. The frequent mention in the younger age group of poverty and economic considerations as a reason for abortion and of the women being compelled to terminate their pregnancies, are rather disconcerting developments, neither of which were reported to the same extent by the older women.

As regards gender power relations within marriage, our data on contraceptive use suggest that never-users of abortion were as exposed to the risk of unwanted pregnancy as ever-users, perhaps more so, other things being equal. One feature that distinguished the two groups was that among the never-users, more husbands “co-operated” in preventing unwanted pregnancies by conceding to their wives' requests to avoid sex. This would explain the lower average number of pregnancies in the never-users group, and also the lower reports of non-consensual sex and sexual violence.

The most noticeable distinction between ever-users and never-users of abortion was the preponderance of non-consensual sex and sexual violence among the former. Although the evidence is not conclusive, there is a strong possibility that many unwanted pregnancies may have been the consequence of unwanted sex and women's inability to refuse their husband's sexual demands. Many men seemed to believe that sex within marriage was their right, and that the women had no say in the matter.

This study raises a number of uncomfortable questions on the presumed association between women's ability to have an induced abortion and their enjoyment of reproductive and sexual rights. A large number of women who have had abortions in this study have been denied their sexual rights but were permitted–sometimes even forced–to terminate their pregnancies for reasons unrelated to their right to choose abortion. It would be worthwhile examining whether the same is true in other settings where women's use of induced abortion is relatively high compared to their use of contraception.

For RUWSEC as an organisation, this study brought home the need to address the issue of sexual violence in marriage within interventions to prevent unwanted pregnancy, rather than focus exclusively on improving access to contraceptive information and services. RUWSEC has held sexuality and reproductive health education workshops for newly married couples in the past. These workshops were welcomed by young men and women not only as an opportunity to learn about sexuality and reproduction, but as a forum to clarify and understand better women's and men's differing perspectives on these matters. It seems important to continue with these workshops on a regular basis and, within them, to address the need for induced abortion as an issue of non-consensual sex.

RUWSEC is also considering how to campaign on the unacceptability of sexual coercion in marriage, in hopes of encouraging a change in the attitudes and behaviour in the younger generations now and in future.

Acknowledgements

Health Watch Trust, India supported the research on which this paper is based as part of the Abortion Assessment Project–India. Technical as well as editing support was provided by the Health Watch Trust for the final report, of which this paper is a shortened version.

Notes

* There were three instances, all among older women, where the number of abortions reported by the woman differed from that reported by her husband. Where either spouse reported an abortion, we have counted it as such.

* A woman was counted as having experienced (sexual) violence or non-consensual sex if these were reported as taking place on an ongoing basis in the course of their reproductive lives.

* Several women experienced both non-sexual and sexual violence.

References

- HB Johnston. Abortion and post-abortion care in India: a review of literature, Draft 3. 1999; Ipas: Chapel Hill NC.

- S Agarwal. Annotated Bibliography on Abortion in India. 2000; Health Watch Trust: New Delhi.

- KP Singh, R Singh. A study of psychosocial aspects of MTP. 1991; Population Research Centre, Department of Sociology, Punjab University: Chandigarh. (Unpublished).

- Seva Sanstha Parivar. A Study on Abortion in Varanasi, Uttar Pradesh. 1999; Parivar Seva Sanstha: New Delhi.

- Sinha R, Khan ME, Patel BC, et al. Decision-making and acceptance in seeking abortions of unwanted pregnancies. Paper presented at International Workshop on Abortion Facilities and Post-Abortion Care in the context of the Reproductive and Child Health Programme. Baroda: Centre for Operations Research and Training, 1998.

- M Gupte, S Bandewar, H Pisal. Women's Role in Decision-Making on Abortion: Profiles from Rural Maharashtra. 1997; CEHAT: Pune.

- International Institute for Population Sciences, ORC Macro. National Family Health Survey (NFHS-2), 1998–99: India. Mumbai: IIPS, 2000.

- International Institute for Population Sciences. National Family Health Survey-I, 1992–93: India. Mumbai, IIPS, 1993.

- US Mishra, M Ramanathan, SI Rajan. Induced abortion potential among Indian women. Social Biology. 45(3–4): 1998; 278–288.

- TKS Ravindran. Women's status and fertility transition in Tamil Nadu: an inquiry into the inter-linkages. UNDP Project on Human Development in India. 1997; Centre for Development Studies: Trivandrum. (Unpublished).

- Population Research Centre, Gandhigram Institute of Rural Health and Family Welfare Trust, Indian Institute of Population Studies. Tamil Nadu: Reproductive and Child Health Project. Rapid Household Survey 1998–99. 2001; Gandhigram Institute of Rural Health and Family Welfare Trust: Gandhigram. (Unpublished).