Abstract

Greece has one of the highest rates of abortions in Europe and a very low prevalence of contraceptive use apart from withdrawal and condoms. Based on limited data from the past 30 years, this paper describes the context in which Greek women make reproductive decisions, and the history of family planning and abortion policies and services in Greece. It shows that in spite of the persistence of the traditional importance placed on marriage and motherhood, the fertility rate in Greece is very low. Sex education is still not included in the school curriculum, and the lack of accurate information on contraception and the prevention of unwanted pregnancy, especially in adolescence, still have critical repercussions for women’s life choices. Although the public sector has been required to provide family planning services since 1980, only 2% of women of reproductive age were accessing these services in 1990, based mainly in urban centres. In 2001, one in four women of reproductive age had had at least one unwanted pregnancy ending in abortion; the rate was one in ten in the 16—24 age group and one in three in the 35—45 age group. With an almost complete lack of preventive policies in Greece, women continue to have to rely on abortion to control births.

Résumé

La Grèce connaît l’un des taux les plus élevés d’avortement en Europe et un niveau très bas d’utilisation de la contraception,àl’exception du retrait et des préservatifs. Se fondant sur des données limitées portant sur les 30 dernières années, l’article décrit le contexte dans lequel les Grecques prennent leurs décisions en matière de reproduction, et retrace l’histoire des politiques et des services de planification familiale et d’avortement dans le pays. Malgré l’importance traditionnellement accordée au mariage etàla maternité, le taux de fécondité est très faible en Grèce. L’éducation sexuelle ne figure pas dans les programmes scolaires et le manque d’information sur la contraception et la prévention des grossesses non désirées, particulièrementàl’adolescence, ont encore de graves répercussions sur les choix des femmes. Bien que le secteur public soit tenu d’assurer des services de planification familiale depuis 1980, 2% seulement des femmes en âge de procréer y avaient accès en 1990, principalement dans les centres urbains. En 2001, une femme en âge de procréer sur quatre avait subi une interruption de grossesse non désirée ; ce taux était d’une femme sur dix dans le groupe des 16—24 ans et d’une sur trois dans le groupe des 35—45 ans. Avec une absence presque totale de politiques de prévention, les Grecques continuent d’avoir recoursàl’avortement pour limiter les naissances.

Resumen

Grecia cuenta con una de las tasas de aborto más altas de Europa y un ándice muy bajo de uso de anticonceptivos, aparte del coitus interruptus y los condones. Basándose en datos limitados de los últimos 30 años, este artáculo describe el contexto en que las mujeres griegas toman decisiones reproductivas, asá como la historia de la planificación familiar y de las poláticas y los servicios de aborto en Grecia. Muestra que, pese a la persistencia de la importancia tradicional otorgada al matrimonio y a la maternidad, la tasa de fertilidad en Grecia es muy baja. Aún no se incluye la educación sexual en el curráculo escolar, y la falta de información exacta sobre la anticoncepción y la prevención de embarazos no deseados, especialmente durante la adolescencia, continúan incidiendo en las decisiones de las mujeres. A pesar de que, desde 1980, se ha exigido al sector público que preste servicios de planificación familiar, en 1990, sólo el 2% de las mujeres en edad reproductiva, de los centros urbanos principalmente, tenáan acceso a éstos. En 2001, una de cada cuatro mujeres en edad fértil habáa tenido por lo menos un embarazo no deseado terminado en aborto; la tasa fue de una de cada diez en el grupo de mujeres de 16 a 24 años de edad, y una de cada tres en el de 35 a 45 años. Debido a la falta casi total de poláticas de prevención en Grecia, las mujeres continúan necesitando recurrir al aborto para controlar la natalidad.

Two major events took place in Greece in the 1980s which could have caused a considerable shift in women’s ability to control their fertility: the development of family planning clinics in 1980 and the legalisation of abortion in 1986. Yet today, 25 years later, Greece is one of the countries with the highest number of abortions and the lowest prevalence of modern contraceptive use in Europe.

This paper describes the socio-cultural context in which many Greek women make reproductive decisions, especially those living outside the major urban areas, and of the policies and services for family planning and abortion in Greece. It draws mainly on research carried out in the 1990s by the Department of Sociology at the National School of Public Health in Athens. Additional information on the past and contemporary context of contraceptive use and abortion came from information gathered by the National Social Research Centre, which has been studying these issues since the early 1970s, articles by gynaecologists, and articles that have appeared in the media, mainly in the last 2—3 years. In order to describe the establishment of family planning services in Greece, an interview was carried out with key informant Dr. Margaritidou, who is the president of the NGO Women and Health Initiative and one of the founding volunteer members of the Greek Family Planning Association, where she has worked for more than 25 years.

Demographic data on Greece

The fertility rate in Greece is among the lowest in Europe, which has fallen from 2.4 in the 1960s to 2.21 in the 1980s and 1.29 in 1999. The infant mortality rate is also low at 6.15 deaths per 1,000 live births. The decline in the fertility rate is related to the increasingly later age at which women have been getting married (from 22.3 years of age in the 1980s to 25.9 in 1998) and the later age at which they are having their first child (from 23.3 years of age in the 1980s to 28.6 in 1998). The great majority of births in Greece occur within the context of marriage. Although the percentage of births outside marriage has risen in the last four decades (from 1.5% between 1956 and 1980 to 3.8% in 1998) the rate is still one of the lowest in Europe.

In 1999 international research on fertility, co-ordinated by the United Nations, was carried out in 30 countries. In Greece, the research included a representative sample of 4,074 men and women aged 18—49 and indicated that although women consider two as the desirable number of children, 34.5% of those who had only one child were not planning to have another one. At the same time, 19% of women in the age group 30—34 had no children at all. The main reasons that couples gave for not reaching their desired number of children were financial and also related to the lack of availability of state family support facilities and services.Citation1

The socio-cultural context of having children: tradition vs. change

Greek society, basically patriarchal within the Mediterranean model, continues to uphold traditional values while at the same time sharing characteristics of a modern and post-modern society. At the current time, the Greek family and gender roles are gradually altering and following the Western European model, though at a slow pace.Citation2 Citation3 Citation4 Citation5 In both urban and rural settings one can find the traditional family with the distinct separation of roles between men and women, with the man responsible for the social sphere and the woman restricted to the domestic sphere. In the semi-traditional familial situation, the man still dominates in the social sphere but the woman is working outside the home and at the same time is responsible for the domestic work and raising of children. In the last 25 years, among younger couples with higher education, a new type of family formation has also occurred, the so-called double career family, in which both partners work and share domestic tasks and the raising of children equally. These changes have occurred in the past two decades at a variable pace for different social and class groups and between urban and rural areas in Greece. Thus, more individualistic choices and life styles are available in urban centres and more often among the middle class and more educated couples than among rural, poor, less educated groups.Citation6

In Greece, the institution of the family remains a core value and has a strong and direct influence on the life-decisions of its members, including in relation to sexuality and marriage.Citation6 Traditionally, there has always been strict control of women’s sexuality, especially in the countryside, with the men of the family responsible for keeping an eye on their daughters and sisters so they do not have sexual relations before or outside marriage. Although this control has diminished to a great extent, it has certainly not disappeared, especially in the countryside. In recent qualitative research in a semi-urban area of northern Greece in 1999,Citation7 married women in the age group 30—45 were asked to talk about their lives (childhood, adulthood, married life, education and work) and to comment on the important turning points. In this context, many of them referred to their entrance into adulthood and mentioned familial control of their behaviour.Citation8 The following quotation from a 43-year-old woman is representative of the situation that many women faced as single girls:

“I didn’t have any love relationships in high school… Our society was so ‘closed’, so strict on women’s lives that we couldn’t do what young people do in the capital or in big cities… We couldn’t go to the cinema, to a café. My father didn’t let me go to the disco or to parties…” Citation7

Marriage is still considered the highest obligation and duty in Greek culture and even today, young people still consider marriage as an important goal in their lives. In a qualitative research study on unemployment among young university graduates in seven European countries in 1999, this attitude was obvious in the narratives of the Greek respondents. Both the men and the women seemed anxious to find work in order to be able to start a family rather than to have a career, which was the reason for anxiety among the young people from northern European countries.Citation9

At the same time, motherhood constitutes an essential part of women’s gender identity in Greece. A survey carried out in 1997 by the National Centre for Social Research among 507 married women aged 15—45 in Athens, on family roles and spousal household practices,Citation4 found a decrease in the number of women aged 25—29 in the labour market and a tendency to re-enter the labour market at the age of 35, clearly a sign that women withdrew from work in order to bring up their children. Bringing up children and housework are still considered women’s tasks by the majority of both men and women. This pattern is slowly changing as the younger and more educated couples appear to be sharing household duties more.

Sex education in schools: limited knowledge, limited life choices

Sex education is still not included in the school curriculum, and only sporadic information is given as part of the lessons in subjects such as health education, and even that is not offered in every school. Health education is a subject that students can select if they are interested, without credits, and it depends entirely on the staff in each school as to whether they include it in the curriculum at all. Many parents are still not convinced of the necessity of such information in schools, and a number of them believe that they should be the ones to discuss sexuality with their children.Citation10 However, this view conflicts with the views of many children, who state that they rarely discuss these issues with their parents and prefer to ask their peers or watch television to get the necessary information.Citation11

The lack of accurate and scientifically-based information on contraception and especially on the prevention of unwanted pregnancy, especially in adolescence, has continued to have critical repercussions for women’s life choices. This was evident in the qualitative research carried out in 1999 in the semi-urban area of northern Greece mentioned aboveCitation7 where women appeared to have limited choices. Women who managed to escape from parental control had no knowledge about contraceptive methods, and in many cases ended up in unwanted pregnancies that often occurred at critical moments in their careers or education. This research brought to light important information about the effects of ignorance on women’s life-course and provided significant information based on the narratives of women. The findings indicated that due to low levels of knowledge about modern contraception, they continued to rely on traditional methods of birth control (withdrawal or the rhythm method) and on abortion. In many cases, marriage was the only possible solution to an unplanned pregnancy, and the family obligations that followed limited the women’s choices in every aspect of their lives. The following comments from women aged 39—44 are typical:

“They [girlfriends] told me that two days before your period comes you can’t get pregnant, so I didn’t need to be afraid. I wasn’t sure and I was a bit scared but they insisted that they were certain and I needn’t be hesitant…So I said OK, let me try…I did it and I got pregnant…At that moment we didn’t want to have a child but since it came we got married…” (Aphrodite, factory worker, 44)

“First I got pregnant and then I was informed about contraception. The very first time I made love, I got pregnant.” (Christina, teacher, 39)

“In high school I met my future husband and the moment we made love I got pregnant. At that time I didn’t want a child… No way…so I had my first abortion. After a year I got pregnant again and then we got married, we didn’t want to have another abortion… After my first child I got pregnant after a short period of time and then I had my second abortion… I regret my decision to get married so young… I didn’t have the opportunity to continue my studies or get an education.” (Maria, housewife, 40)

In the same research,Citation7 young girls aged 16—18 who took part in a focus group discussion discussed issues of sexuality and knowledge of contraceptive methods. Although the situation had changed and parents did not exercise the same control as the older women had experienced, the younger girls appeared to be anxious about what the “right” age was to start sexual relations and talked about the consequences for a woman who starts “too early”, both physically and morally. Real facts and stereotypes seemed to be floating around the axes of what was moral and immoral. At the same time lack of accurate information on contraceptive methods had resulted in fears and doubts about their use. Some indicative comments of young girls were the following:

“It is not good to make love at 17 because later on you will have gynaecological problems….” (Antigone, 17, student, 11th grade)

“The pill is good because they say you don’t get pregnant if you take it… but I have heard that in the future you will not be able to have children…” (Sofia, 16, student, 10th grade)

Limited family planning services within primary health care: some history

Family planning only became a subject for public discussion in Greece in the 1960s, and the original orientation of these discussions was more about eugenics than the provision of family planning services as a human right.Citation12 In the 1970s, women’s organisations became active in matters of abortion and contraception. A big discussion started on the estimated 300,000 illegal abortions performed each year at that time.Citation12 Information on contraception was virtually non-existent, with abortion being the only way to resolve an unwanted pregnancy. The women’s movement had a highly dynamic presence in the fight to sensitise the state and organised protest marches and speeches throughout the country, producing informational material, releasing statements and bringing pressure upon the government.Citation13 During this period, a number of volunteers set up the Greek Family Planning Association (GFPA), specifically Dr. Kintis, an independent gynaecologist, who proposed the founding of this NGO to a Greek congresswoman, Mrs. Tsouderou. Seven volunteers, including Dr. Kintis, Mrs. Tsouderou, several health professionals, a sociologist and the president of the Association of Greek Housewives, launched the organisation in 1976. A small family planning clinic was set up in central Athens, run by volunteers, and seminars aiming at the sensitisation of health professionals and the public concerning modern contraceptive methods were organised (Dr. V. Margaritidou, personal communication, March 2004).

In 1980 the Minister of Health, Welfare and Social Insurance, Mr. Doxiadis, established family planning in the public sector by law,Citation14 with the opening of up to ten family planning centres in selected major urban hospitals. According to Dr. Margaritidou, this was achieved mainly by the personal intervention of Mrs. Tsouderou.

In 1983 the Greek National Health System was establishedCitation15 and in Article 15, it incorporated information and education on family planning issues and provision of family planning methods among its targets. The intention was to open a family planning centre within each provincial hospital and for all health centres to be able to provide family planning services.Citation16 Health centres are located in urban and semi-urban areas and family planning was meant to be an integral part of the primary health care services they offered.

During the 1980s, with the support of the national government, more family planning centres were set up around the country. In 1990, the Ministry of Health, Welfare and Social InsuranceFootnote* listed 46 such family planning centres (FPCs) as functioning.Citation12 The main services offered were counselling, contraception and health education. In addition, services concerned with gynaecological pathology were also available, such as breast examination and Pap smear tests. The centres in the central hospitals were staffed by an obstetrician, a midwife, a visiting nurse and a social worker. The role of the doctor — and of the midwife who, in many cases, often replaced the absent doctor — was to do antenatal check-ups, take Pap smears, insert IUDs and carry out breast examinations. The visiting nurse was responsible for providing sex education to the community, including in schools, to produce informational material and to determine the target group for interventions relevant to local needs, e.g. for young people, migrants, sex workers and so on.

In 1990, the Greek Family Planning Association (GFPA) undertook an evaluation of the 46 FPCs, which was financed by the IPPF Europe Region and the General Secretariat of Equality in Greece.Citation12 The aim of the study was to evaluate the effectiveness and coverage of the centres. The findings are all we have today, as there has never been another attempt since then to evaluate the operation of these centres.

Questionnaires were sent to 164 staff listed as working in 46 of the FPCs (not all of them were adequately staffed). Questionnaires were received from 44 staff members at 20 of the FPCs, including eight FPCs operating in the two major cities and 12 in small towns. These included 19 midwives, 13 doctors, 8 health visitors and 4 social workers.

Of the 52 prefectures into which Greece is divided, only 23 had FPCs. Twenty-five of the functioning FPCs were located within acute care hospitals, not in primary health care clinics. Only ten were in primary health care clinics, run in co-operation with local authorities, with the remaining three run as extension services of three of these. All of the clinics were open in the morning but only two in the afternoon, and most of them reported being understaffed.

The conclusion of the evaluation was that the FPCs were responding to the needs only of a very limited section of the population.Citation12 Only about 2% of women of reproductive age (15—44) were using the services. The prefectures and areas either without an FPC or with inadequately functioning centres were predominantly the more rural and remote ones, with associated lower-than-average income levels.

There appeared to be no unified policy or practice in the orientation of the services provided by these FPCs.Citation12 One in three of them appeared to be almost entirely concerned with gynaecological problems, and the distinction between them and the gynaecological departments of the hospitals to which they were attached was not clear.

No records were being kept on the age of clinic users but staff estimated that women aged 26—40 used the FPCs most frequently and those aged 18—25 frequently, but those under 18 only rarely. Staff reported that the attendance of couples or men on their own was very rare, given the tendency of the FPCs to focus on gynaecological pathology. While all FPCs had printed informational material available, the majority of the leaflets were about Pap smears and breast self-examination. Only six centres had adequate printed information on the range of contraceptive methods.

In 2003, the Ministry of Health and Welfare provided the authors with a list of 41 FPCs functioning in Greece. Twelve of these were operating within hospitals in the greater metropolitan area of Athens and Piraeus. Three were in Thessaloniki and 22 in hospitals on the mainland; Crete was the only island with any coverage, with four FPCs.

Low contraceptive use

There are no official data on the use of contraceptive methods or the percentage of the population that are using a method in Greece. The available data derive either from research studies Citation1 Citation7 Citation17 Citation18 Citation19 Citation20 or from the records of some of the family planning and gynaecological clinics.Citation21 Citation22 Citation23

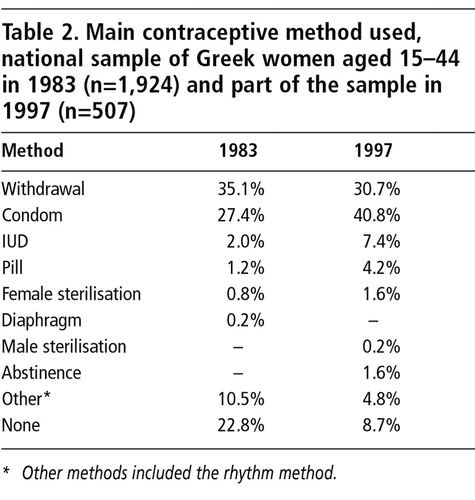

Greek society has not fully adopted the use of modern methods of contraception, even though they were first introduced in the late 1970s, and the country appears to have one of the lowest rates of modern contraceptive use in Europe. Only 2—3% of women of reproductive age use the pill (compared to 30—40% in Western Europe) and 4—10% the IUD. The use of condoms was introduced through AIDS prevention campaigns not long after other modern contraceptive methods were introduced and was widely adopted. Indeed, condom use and coitus interruptus were and still are the two most familiar and commonly used methods, according to research data.Citation17 In addition, induced abortion is widely used, and women mostly appear to be using it as a primary method of birth control rather than as a back-up in cases of contraceptive failure.Citation21 Citation22 Citation23

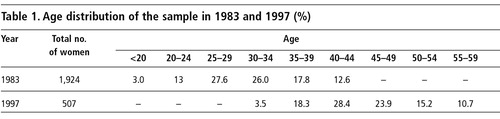

In 1983, the National Centre for Social Research (EKKE)Citation18 carried out a study on the desired versus the actual number of children being born into Greek families, through a representative national sample of 1,924 women from different age groups from 15 to 44. The study included questions on contraceptive methods and abortion. In a follow-up study 15 years later, in 1997, the researchers managed to locate 507 of the same women, who were aged 30—59. In , the age distribution of the sample is presented, and in the main contraceptive methods used. As many women in the sample had entered the menopause by 1997, they were asked about contraceptive methods used after 1983, so as not to skew the results.

The decrease in the use of no method is statistically significant and there was a slight increase in the use of the pill and condom (the latter mainly as a result of AIDS education campaigns). However, the overall low use of the most efficacious contraceptive methods has led to high numbers of abortions. The percentage of women who had never had an abortion decreased from 64% in 1983 to 54% in 1997, while the percentage of women with three or more abortions doubled from 9% in 1983 to 18% in 1997.Citation18 This study indicates that the high number of abortions is a significant factor in the reduction in births and fertility rates in Greece, along with other socio-economic characteristics and with the increase in women’s employment.Citation18

The most recent national survey on contraceptive use was carried out in 2001 by the Institute of Social and Preventive Medicine among a representative sample of 1,500 individuals (1,422 sexually active, 744 women and 678 men) aged 16—45. Among this sample, 50% said they were using condoms, 21.7% withdrawal, 4.8% the pill and 3.6% the IUD. One in four women had had at least one lifetime unwanted pregnancy that ended in induced abortion. Significantly, 54.3% of the sample believed the man was the one who must decide on and use a contraceptive method, and this percentage was higher (64.3%) among the younger age group, 19—24.Citation19

High rates of abortion

The first published data on induced abortion go back to 1965, in a study carried out by Valaoras et alCitation20 among a national sample of 6,513 married women, aged 20—50. They found a 1:1 ratio between abortions and births among the women interviewed.

Indicative of the wide acceptance of abortion among Greek couples are the results of a comparative study of young couples carried out in 1972 in the metropolitan area of Athens by the National Social Research CentreCitation24 and in Louvain, Belgium, co-ordinated by Professor of Sociology Dr. Presvelou there. A representative sample of 366 young couples in the Athens area who were under the age of 32, had been married less than ten years and had had at least one child born in 1967 or 1968 were interviewed. Both the men and the women were asked, separately, if they agreed that an unwanted pregnancy might end in abortion. The large majority of men and women (54.6%) in Greece agreed with the statement, while in Belgium 39.5% of men agreed and 28.8% of women. The researchers interpreted this positive attitude of both men and women towards abortion as one of the effects of the lack of sex education in schools.

In 1992 the Non-Aligned Women’s Movement launched a campaign for “legal and safe abortions”. The aim was to spread information on safe contraception and on the need to render these health services more accessible. They argued that despite the fact that abortions in Greece were legal and covered by insurance funds, some women were being treated in a hostile way by doctors and social workers in the public hospitals.Citation13

In 1998, at the 4th International Gynaecological Conference in Athens, Dr. Kreatsas of the Obstetric and Gynaecology Clinic of Areteio Hospital in Athens, where one of the biggest family planning centres operates, presented data from the clinic’s records for the years 1975—96, which showed that the proportion of abortions among adolescent girls aged 14—19 had risen from 28.8% in 1975 to 35% in 1996.Citation25

In the 17th Medical Conference of Northern Greece in 2002, Professor of Gynaecology and Obstetrics I. Bontis said that from 1980—99 there had been a decline in fertility in Greece of 41%. Although there may be many reasons for this decline, Bontis argued that it was a consequence of unsafe abortions because the 150,000 Greek women who suffer from infertility have a history of at least one abortion.Citation26 The same argument has been made by Dr. Tarlatzis, who argues that women’s infertility in Greece is caused by gynaecological problems resulting from unsafe abortions.Citation23

The country report in 2000 for the European Women’s Health NetworkCitation13 Footnote* states that in the past, when abortions were illegal, the state turned a blind eye to the problem and women had abortions in private clinics and doctors’ surgeries. The report claims that this often resulted in women having post-abortion complications with repercussions for their health and fertility. There are unfortunately no official data available on the total number of abortions or to show whether or not abortions are safer today.

The data held by the National Statistical Service of Greece refer only to abortions taking place in National Hospitals, which do not represent the whole picture. According to the National Report of the General Secretariat of Equality in Greece (2000),Citation16 the total number of abortions registered in national hospitals is 100,000—120,000 per year. This is equal to the number of births per year and makes the abortion rate one of the highest in Europe at 100—120 per 1,000 women per year, compared to 20—30 in Austria and 25 in the Netherlands.Citation27

Gynaecologists present different figures. The representatives of the Greek Family Planning Association, at the 2nd National Conference on Reproductive and Sexual Health: Trends and Possibilities in the New Century, in 2000, reported that although the number of registered abortions is at least 100,000 per year, unregistered abortions are estimated to reach 300,000.Citation28

The Institute of Social and Preventive Medicine, in the 2001 survey mentioned earlier,Citation19 found that one in four women of reproductive age had had at least one unwanted pregnancy ending in abortion in their lifetime. The rate was one in ten in the age group 16—24 and as high as one in three in the age group 35—45.

In contrast, the General Secretariat of Equality Report (2000) states that the rate of abortions has declined in recent years, and that the higher figures refer in great part to abortions among migrant women, mainly from the former Soviet countries, who have constituted a considerable proportion of the population in the past decade and who also have a history of dependence on abortion. The Report further argues that the legalisation of abortion in 1986 and the development of the FPCs in the 1990s have contributed to this reduction.Citation16 In the absence of accurate data in this regard, the opposite view can still also be considered, however, especially since the FPCs are serving such a low proportion of the population, and that legalisation by itself has not appeared to change the situation for abortion very much in the past 20+ years.

Discussion

The lack of official data on contraceptive use and number of abortions makes it impossible to investigate these issues in any depth. Public hospital-based gynaecology clinics collect data (e.g. age, marital status, rate of repeat abortions) but the records of private sector providers are not easily available for investigation.

In the Greek National Health System, abortions are carried out free of charge. The costs are covered by health insurance, which includes the right to three days’ leave on full pay. For young women under 18, parental consent is necessary. However, most women continue to use the private sector for abortions,Citation29 where an abortion today costs about 1,000 Euros, an amount that is generally considered cheap. Even in 1994, Tseperi and MestheneosCitation30 discussed the paradox of Greek women who are unwilling to use the public family planning and abortion services, even though they are free, and prefer to pay for a private abortion. They argue that this is because private abortions are usually performed immediately, in contrast to public hospitals, where bureaucratic procedures cause delays. Another reason might be the hostility women experience in the public hospitals.

The question that still needs to be answered is why women and especially young women today continue to rely on abortion? There are different factors that need to be taken into consideration. Those related to the personal and socio-cultural aspects of the subject cannot be discussed here, due to the absence of data on the sexual and reproductive behaviour of women and men in contemporary Greece, which does not permit us to go deeper into these issues. In 1991, Naziri attempted to give a psychological explanation for this phenomenon and linked the practice of abortion to resistance to the symbolic and actual meaning of modern contraception because of the traditional importance of the mothering role. According to her, “the unwanted pregnancy reveals the profound and unconscious need of both men and women to prove their fertility, upon which modern contraception might cast doubt, even if temporarily.Citation31 Presvelou and Teperoglou in 1976 examined this phenomenon sociologically and concluded: “In the Greek context, abortion is an element of everyday routine and experience. It is not related to financial factors nor to modern ideas and it is not related to gender differences.Citation24

It is interesting that apart from these studies, there has been no other research on this issue. The only data related to abortion come from individual gynaecologists in presentations at conferences. At the same time, women’s organisations in recent years appear to be focusing on other topics such as trafficking, HIV/AIDS, cancer and drugs, but not on abortion.Citation13 There seems to be no interest in investigating this issue further on the part of the state or private bodies who are involved either. Hence, it is not easy for social researchers such as myself to find the financial resources necessary to conduct longitudinal, qualitative research on these matters, for which speculation is possible today.

It is evident, however, that there has been a failure on the part of the government and the health system to provide comprehensive family planning services, despite the prioritisation of primary health care services by the Ministry of Health and Social Solidarity. The reasons are easily identifiable: absence of sex education in schools, lack of health promotion campaigns on modern contraceptive methods, and the limited number of FPCs, especially outside of urban centres. In short, there is an almost complete lack of preventive policies in relation to abortion. At the same time, the government appears to have difficulties in separating the demographic problems of Greece, including the ageing population and low fertility rate, from the right to family planning services. This might be yet another reason why there is little emphasis on improving the functioning of FPCs as family planning providers in more than name only.

Moreover, there is a lack of public demand for sex education, information on contraception or the development of comprehensive family planning services. Many gynaecologists fail to inform and educate their patients about the existence and benefits of different contraceptive methods, as they make a good profit out of abortions. In 2003, a newspaper article estimated that the money Greek women spend on abortions had reached 150 million Euros annually.Citation29 The article argues that gynaecologists must take tremendous responsibility for not informing their patients about modern contraceptive methods because the financial gain from abortions is so high.

As the younger generation continues to rely on abortion and has not adopted any other form of contraception, emergency contraception might become a method used in greater numbers in future. The NGO Women and Health Initiative has set up an open telephone information line and promotes emergency contraception, including through a campaign on television. According to Dr.Margaritidou, the pharmaceutical company PN Gerolymatos, SA, which distributes these pills in the Greek market, reported that 100,000 sets of emergency contraception pills were sold by Greek pharmacists in 2002, rising to 80,000 up to September 2003. This, it is estimated, could lead to a decline in the number of abortions in the future though it is too early to make any assessments at this stage (Dr. V. Margaritidou, personal communication, March 2004).

In order to pave the way for a change in attitude towards abortions, the following interventions should be considered:

| • | Sex education in every school in the country. | ||||

| • | Systematic and thorough planning, provision and evaluation of family planning services. | ||||

| • | Systematic collection of data on contraceptive use and abortion in the public and private sectors by the Ministry of Health and Social Solidarity. | ||||

| • | Sociological research to study the family planning behaviour of the younger compared to the older generation. | ||||

| • | A gender approach integrated into the policy framework regarding sexual and reproductive health care and other health policies and services. | ||||

Notes

* The Greek Ministry of Health has changed its name several times, first from the Ministry of Health, Welfare and Social Insurance to the Ministry of Health and Welfare; then the last government changed the name to the Ministry of Health and Social Solidarity.

* The European Women’s Health Network (EWHNET) is a project in the 4th Medium-Term Community Action Programme on Equal Opportunities for Women and Men (1996—2001) and is supported financially by the Federal Ministry of Family Affairs, Seniors, Women and Youth (BMFSFJ).

References

- H Symeonidou. Fertility. A Mouriki, M Naoumi, G Papapetrou. The Sociala Profile of Greece 2001. National Center of Social Research, Institute of Social Policy. 2002; EKKE Athens. 27–31.

- L Alibranti-Maratou, R Fakiolas. The lonely path of migrant women in Greece. E Alipranti-Maratou, L Tatsoglou. Gender and International Migration: Focus on Greece. 2003; EKKE Athens. 165–188.

- H Katakis. The Three Identities of the Greek Family. 1984; Kedros Athens.

- L Alibranti-Maratou. Family in Athens: Family Patterns and Spouses’ Practices. 1999; EKKE Athens.

- L Mousourou. Sociology of the Modern Family. 1989; Gutenberg Athens.

- E Mestheneos, E Ioannidi-Kapolou. Gender and family in the development of Greek state and society. P Chamberlayne, M Rustin, T Wengraf. Biography and Social Exclusion in Europe: Experiences and Life Journeys. 2002; Policy Press London. 175–192.

- D Agrafiotis, E Ioannidi. Ch Tselepi Sexual health of women in adolescence and reproductive age in the area of Serres. INTERREG II, Research Monograph No.21. 2000; Department of Sociology, National School of Public Health Athens.

- J Dubisch. Gender and Power in Rural Greece. 1986; Princeton University Press Princeton.

- E Mestheneos, E Ioannidi. Cocooned or trapped? Unemployed Graduates, Social Strategies in Risk Societies. SOSTRIS, Working Paper 7. 1999; Centre for Biography in Social Policy, Sociology Department, University of East London London.

- E Ioannidi-Kapolou. Attitudes of Greek parents towards sexual education Choices, Sexual Health and Family Planning in Europe. 28(1): 2000; 14–18.

- E Ioannidi, D Agrafiotis, A Douma. AIDS: Knowledge, attitudes, beliefs and practices of young people for STDs and sexual practices Hellenic Dermato-Venereological Review. 1(Suppl.): 1990; 399–401.

- V Margaritidou, E Mestheneos. Evaluation of the family planning services. 1991; Greek Family Planning Association Athens.

- Women’s Health Network. State of Affairs, Concepts, Approaches, Organisations in the Women’s Health Movement. Country Report. Greece. September, 2000.

- Government Newspaper Issue (FEK), Law 1036/80. 1980; Ministry of Health, Welfare and Social Insurance Athens.

- Government Newspaper Issue (FEK), Law 1323/83, Article 15. 1983; Ministry of Health, Welfare and Social Insurance Athens.

- General Secretariat for Equality. 4th and 5th National Report of Greece (1994—2000) to CEDAW. Athens, 2000.

- E Ioannidi, I Mitropoulos, D Agrafiotis. Sexual behaviour and risks of HIV infection in Europe: the case of Greece. Hellenic Archives of AIDS. 8(2): 2000; 105–111.

- Ch Simeonidou. Desired and Real Size of Family. Events of a Life Cycle. A Longitudinal Approach: 1983—1997. 2000; EKKE Athens.

- Institute of Social and Preventive Medicine. National survey on contraception. 2001; Metron Analysis Athens.

- B Valaoras, A Polychronopoulos. Control of family size in Greece: the results of a field survey. Population Studies. 18: 1965

- G Kintis. Socio-medical dimensions of abortions. A Roumeliotou, E Kornarou, M Gitona. Health and Women. 1996; Department of Epidemiology, National School of Public Health Athens.

- V Tarlatzis. Contraception and reproductive health. New Health. 34: 2001; 6.

- D Triantafyllou. Panhellenic research on contraception. New Health. 34: 2001; 8–9.

- K Presvelou, A Teperoglou. Sociological analysis of the phenomenon of abortion in the Greek context. Greek Review of Social Research. 28: 1976; 275–286.

- Ta NEA (Athens). 18 November 1998. p.15.

- Greece international champion: abortions responsible for 150,000 infertile couples. Eleftherotypia. 13 April 2002.

- I Garcia-Sanchez, S Prinzon-Pulido, L van Mens. Situation analysis: European overview. L van Mens. Prevention of HIV and STIs among Women in Europe, PHASE. 2002; Plantijn Casparie Utrecht. 13–24.

- Kreatsas G. Sad first place in abortions. Apogeymatini. 16 February 2000.

- We spend 50 billion drs. for abortions. Investors World (Athens). 30 March 2003.

- P Tseperi, E Mestheneos. Paradoxes in the costs of family planning in Greece. Planned Parenthood in Europe. 23(1): 1994; 14.

- D Naziri. The triviality of abortion in Greece. Planned Parenthood in Europe. 20(2): 1991; 12–14.