Abstract

In Mexico, recent political events have drawn increased public attention to the subject of abortion. In 2000, using a national probability sample, we surveyed 3,000 Mexicans aged 15—65 about their knowledge and opinions on abortion. Forty-five per cent knew that abortion was sometimes legal in their state, and 79% felt that abortion should be legal in some circumstances. A majority of participants believed that abortion should be legal when a woman’s life is at risk (82%), a woman’s health is in danger (76%), pregnancy results from rape (64%) or there is a risk of fetal impairment (53%). Far fewer respondents supported legal abortion when a woman is a minor (21%), for economic reasons (17%), when a woman is single (11%) or because of contraceptive failure (11%). In spite of the influence of the Church, most Mexican Catholics believed the Church and legislators’ personal religious beliefs should not factor into abortion legislation, and most supported provision of abortions in public health services in cases when abortion is legal. To improve safe, legal abortion access in Mexico, efforts should focus on increasing public knowledge of legal abortion, decreasing the Church’s political influence on abortion legislation, reducing the social stigma associated with sexuality and abortion, and training health care providers to offer safe, legal abortions.

Résumé

Au Mexique, de récents événements ont mis l’avortement au centre de l’attention publique. En 2000,àpartir d’un échantillon aléatoire national, nous avons interrogé 3000 Mexicains âgés de 15à65 ansàpropos de leurs connaissances et leurs opinions sur l’avortement. Ils étaient 45%àsavoir que l’avortement est parfois légal dans leur Átat et 79% pensaient qu’il devait l’Átre dans certaines circonstances. Une majorité de répondants estimaient que l’avortement doit Átre autorisé si la vie (82%) ou la santé (76%) de la femme est en danger, si la grossesse résulte d’un viol (64%) ou si le Fatus présente des anomalies physiques ou mentales (53%). Nettement moins de personnes approuvaient l’avortement légal pour une mineure (21%), pour des motifs financiers (17%), si la femme est célibataire (11%) ou en raison d’un échec de la contraception (11%). Malgré le pouvoir de l’Áglise, la plupart des catholiques jugeaient que l’Áglise et les convictions des législateurs ne devaient pas peser sur la législation, et la plupart approuvaient la pratique d’avortements par les services de santé publics dans les cas autorisés par la loi. Pour améliorer l’accèsàl’avortement légal et médicalisé au Mexique, il faut informer la population, diminuer l’influence politique de l’Áglise sur la législation relativeàl’avortement, atténuer la stigmatisation associéeàla sexualité etàl’avortement, et former les prestataires de soins de santéàproposer des avortements légaux et médicalisés.

Resumen

En México, los últimos sucesos poláticos originaron una atención amplia del público hacia el tema del aborto. En el 2000, mediante una muestra de probabilidad nacional, encuestamos a 3,000 mexicanos entre los 15 y 65 años acerca de sus conocimientos y opiniones sobre el aborto. El 45% sabáa que el aborto a veces es legal en su estado, y el 79% estimaba que el aborto debe ser legal en algunos casos. La mayoráa estimó que el aborto debe ser legal cuando la vida de la mujer está en riesgo (82%), la salud de la mujer está en peligro (76%), el embarazo es producto de una violación (64%) o el feto tiene defectos mentales o fásicos (53%). Un número mucho menor de respondedores apoyaron la interrupción legal del embarazo cuando la mujer es menor de edad (21%), por motivos económicos (17%), cuando la mujer es soltera (11%) o debido a falla anticonceptiva (11%). A pesar de la influencia de la Iglesia, la mayoráa de los mexicanos católicos estiman que la Iglesia y las creencias religiosas de los legisladores no deberáan incidir en la legislación sobre el aborto, y la mayoráa apoyó la prestación de servicios por la salud pública en casos en los que éste es legal. A fin de mejorar el acceso al aborto seguro y legal en México, los esfuerzos deben centrarse en crear mayor conciencia entre el público respecto al aborto legal, disminuir la influencia polática de la Iglesia sobre la legislación de aborto, reducir el estigma social asociado con la sexualidad y el aborto, y capacitar a los profesionales de la salud para que provean abortos seguros y legales.

In 2000, an estimated 68,000 women lose their lives globally due to complications of unsafe abortions,Citation1 the great majority in countries with highly restrictive abortion laws.Citation2 Citation3 Citation4 Not only do these laws create a subculture of clandestine, unsafe abortion, they also reinforce an environment in which abortion is socially shameful and unacceptable.Citation5, Citation6 In Mexico, although accurate data on the number of abortions practised is unavailable, complications from unsafe abortions are estimated to be the third or fourth leading cause of maternal mortality,Citation7, Citation8 and legal access to abortion is highly restricted. Each Mexican state decides its own abortion laws. Currently, the only circumstance for which abortion is permissible in all 31 states and in Mexico City is when a pregnancy results from rape. Abortion is also permissible when performed to save a woman’s life in Mexico City and all but two Mexican states. Only the state of Yucatan allows for legal abortion in the case of economic hardship.Citation9 Citation10 Citation11 Citation12

Over the past five to ten years, several key political and legislative events have drawn increased public attention to the topic of abortion in Mexico. In 1997, when the Democratic Revolutionary Party (PRD) came to power in Mexico City, its platform included the decriminalisation of abortion. More recently in 1999, the notorious “Paulina case” in which high-ranking hospital officials coerced a 13-year-old Mexican rape victim and her mother into retracting their request for a legal abortion, drew unprecedented press coverage to the abortion debate.Citation13 Citation14 Citation15

In August 2000, the Mexico City government expanded the grounds on which abortion is legal to include when a woman’s health is at risk and when a fetus has severe congenital malformations.Citation16, Citation17 The law previously only allowed abortion when a pregnancy resulted from rape or when the woman’s life was at risk. The same year, after two public opinion polls conducted in Guanajuato state demonstrated support for legal abortion in certain circumstances, the state governor vetoed a bill that would have made abortion in the case of rape a punishable crime.Citation18 Since 2000, although there have been few legislative “victories” directly related to abortion, in January 2002 the Mexican Supreme Court defended the constitutionality of liberal amendments to the Mexico City abortion laws. The state of Morelos subsequently followed suit, and also liberalised its laws. In January 2004, after years of debate, emergency contraception was finally recognised as a family planning method in Mexico’s official health norms, although many anti-choice groups had opposed it, claiming it created an opening for legalising abortion. In addition, several Mexican NGOs have recently mounted public information campaigns on access to legal abortion and the number of public sector hospitals providing legal abortion services nationwide is rising.

Recent attention to abortion has occurred during a unique political period in Mexican history. In 2000, with the presidential election of Vicente Fox, the 71-year single-party congressional and presidential rule of the Institutional Revolutionary Party (PRI) was ended.Citation18, Citation19 This gave citizens clear evidence of their voting power and more motivation to use it, and has increased legislators’ accountability to the public.Citation19 In this context, the public’s views regarding abortion law could potentially play a greater role in creating change in Mexico.

Previous public opinion surveys in Mexico

Prior to 2000, the most recent national-level abortion opinion polls were carried out seven to ten years earlier.Citation20 Other more recent surveys of abortion public opinion have been conducted in Mexico City and the state of Guanajuato, but these results are not generalisable to Mexico as a whole.Citation21, Citation22

Some of these previous polls suffered methodological problems. Research on survey techniques demonstrates that the measurement of public opinion on abortion is greatly affected by the design, wording and order of questions of surveys and can be manipulated to elicit skewed answers toward a more anti-choice or pro-choice stance.Citation23 Citation24 Citation25 Although quite helpful as advocacy tools, previous surveys in Mexico included the use of non-specific questions, yielding vague answers, as well as “leading” questions eliciting particular responses.Citation26, Citation27

For these reasons, we decided to carry out a national-level study of Mexicans’ knowledge and opinions on abortion.

Sampling methodology and participants

Sampling and field research

The Population Council’s Institutional Review Board reviewed and approved our protocol and instruments. In September and October of 2000, we contracted a market research firm, Grupo Investigación de Mercado (Grupo IDM) to interview a random probability sample of 3,000 Mexicans, aged 15—65, in their households regarding their knowledge and opinions on abortion. We chose our sample using national household data from the National Institute of Statistics, Geography and Information (INEGI), similar to that used for the Mexican census.Citation28 With a sample of 3,000, our survey margin of error was ±1.82%, with 95% confidence, for national level point estimates.

We sampled our study population proportional to the distribution of the Mexican population, living 75% in urban and 25% in rural areas, and residing in six geographical regions (Pacific North 9%, North Central Gulf 18%, Bajio 17%, Central 18%, Metropolitan Mexico City 19% and the Southeast 20%).Footnote* We drew a random sample of municipalities and towns from all states in each region; seven of the 31 states plus Mexico City were not represented in our sample.Footnote* While we can obtain reliable point estimates at the national and regional levels, we do not have representative data at the state level.

Teams of five trained interviewers and one field leader travelled to selected municipalities and towns to conduct fieldwork. The leader selected random blocks and households using INEGI neighbourhood dwelling maps. After determining a random starting point, interviewers chose one eligible participant between the ages of 15 and 65 at each selected household using a table of random numbers. They asked each person selected for their informed consent to participate in a brief, 30-minute survey on a topic related to health.

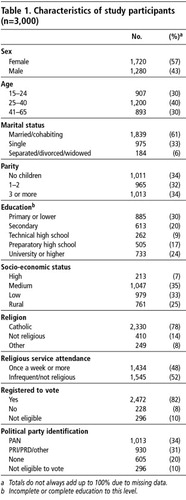

Of 3,061 potential participants, 61 (2%) declined to participate due to: no time (75%), illness (8%), not liking surveys (7%), being against abortion or not wishing to participate in a survey on abortion (4%) and other reasons (6%). Participant characteristics are presented in .

Questionnaire design

We reviewed many questionnaires from previous abortion opinion surveys prior to designing our instrument.Citation20 Citation22 Citation26 We circulated a full draft to several Latin American and US colleagues, including social scientists with expertise in abortion research; directors of Mexican NGOs supportive of women’s reproductive and sexual rights; Population Council colleagues, including demographers, physicians, epidemiologists and statisticians; and a handful of colleagues at survey market research firms.

In designing our survey, we aimed to build questions that avoided some of the common problems in previous surveys. For example, rather than ask, “Who should decide about having an abortion?” we asked, “When a woman is faced with the decision to have an abortion or not to have an abortion, who do you think would be the most appropriate person to help advise her?” We reframed the question to reflect more accurately a woman’s initial role in decision-making, and explicitly noted that a woman’s decision may be not to have an abortion. To avoid questions that would elicit skewed responses, we presented all possible agreement options in the question, tried to provide adequate ranges to multiple-agreement questions, included responses reflecting both pro-choice and anti-choice views, and had interviewers systematically rotate possible responses, since a tendency exists for respondents to choose the first option they hear.

The draft instrument underwent eight revisions prior to pilot testing, with two subsequent revisions and an observation of six women and men who responded to the questionnaire with an interviewer through a one-way window.

Data analysis

All data were entered, organised, and coded using Excel 9.0 and were imported into Stata (8.0, College Station, TX) to conduct statistical analyses. We used multivariate logistic regression to model factors associated with having accurate general information about abortion laws, and with having “pro-choice” or “anti-choice” views on abortion law.

The outcome variable in our logistic regression model exploring factors associated with having accurate information about abortion laws was an indicator of whether participants knew that in their state abortion was legal under certain circumstances. Since Mexican abortion laws vary by state, we chose this general indicator of information rather than asking about the specific circumstances in which abortion is legal. A limitation of this measure is that participants might have had correct general information about the laws, but incorrect information about those specific to their state.

Our analysis of opinions on abortion law was based on a question asking participants which of the following three statements most accurately reflected their views on abortion: “By law, a woman should have the right to an abortion when she so chooses”; “By law, abortion should be permitted only under certain circumstances”; or “By law, abortion should be prohibited in all cases”. We classified participants who indicated that a woman should have access to abortion whenever she chooses as “pro-choice”, those who indicated that abortion should always be prohibited as “anti-choice”, and those who thought that abortion should be allowed only under some circumstances as having an “intermediate” view. We carried out two multiple logistic regression analyses to explore the variables associated with having either an anti-choice or pro-choice view. Our first model compared those who were anti-choice to everyone else in the sample and our second model compared those who were pro-choice to everyone else in the sample.

Since one of our key interests was to evaluate how beliefs about abortion law are associated with opinions, we included two variables reflecting beliefs in our analyses. The first was an indicator of whether participants knew that abortion was legal in their state under some circumstances. The second was a variable measuring whether participants believed maternal mortality would increase, decrease or stay at the same level if Mexico’s abortion laws were liberalised. The other variables we considered in our analyses were age, region, religion, education, religiosity, residence, political party affiliation, marital status, parity, knowing someone who had had an abortion and socio-economic status.

We used forward selection to build our logistic regression models. Once we found all significant predictors of our outcomes, we systematically checked that the variables excluded from our models were not confounders. We also checked for effect modification of sex, rural/urban status, and frequency attending religious services by religion. We evaluated the fit of our models using the Hosmer-Lemeshow goodness-of-fit test,Citation29 and concluded that all of our models adequately fit the data. Our tables show odds ratios and 95% confidence intervals for all variables achieving statistical significance at an alpha level of 0.05.

Knowledge about abortion laws

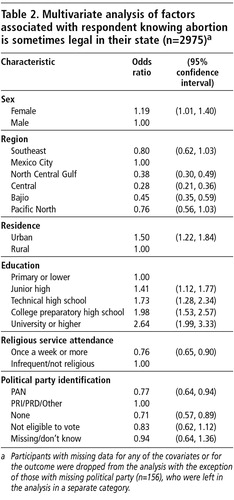

We found that less than half of the respondents (45%) knew that in their state of residence, abortion is legal under certain circumstances. Of those with incorrect information, 79% believed that abortion was illegal in all circumstances. Results from our multivariate model indicated that correctly knowing that abortion is legal under certain circumstances varied by region, education, sex, political party affiliation, frequency attending religious services and residence ( ).

The generally low level of knowledge about Mexican abortion laws likely reflects the true inaccessibility of legal abortion. That is, many Mexicans may believe abortion is illegal in all circumstances because they have not had any prior experience, direct or indirect, with obtaining a legal abortion or because their information sources about legal abortion are unreliable.Citation6

General attitudes towards abortion

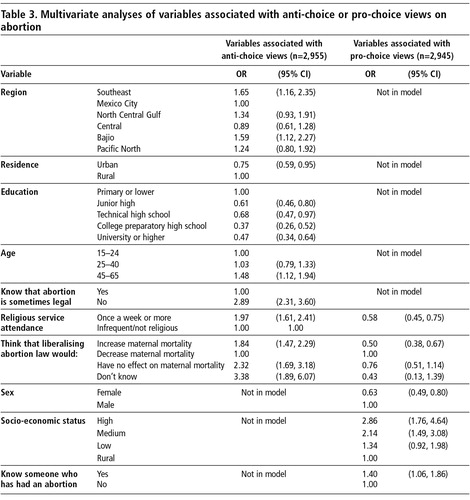

Of the respondents, 69% felt that abortion should be permitted under certain circumstances, 10% that abortion should be available when a woman so chooses, and 21% that abortion should always be prohibited. In , we present our multivariate analyses of variables associated with having an anti-choice or a pro-choice view. Rural residence, living in the Bajio region or the Southeast as compared to Mexico City, having low education, frequently attending religious services, and being aged 41—65 as opposed to age 15—24, were all associated with a higher odds of being anti-choice. Our two variables measuring beliefs about abortion law were also strongly associated with anti-choice views. Respondents who did not know that abortion was sometimes legal in their state had nearly three times the odds of being anti-choice compared to those who did know. Those who thought that liberalising abortion law would lead to an increase in maternal mortality had an 84% higher odds of being anti-choice than those who thought that liberalising the law would decrease maternal mortality.

In our model of pro-choice opinions, we found that being male, of higher socio-economic status and knowing someone who has had an abortion were all associated with an increased odds of being pro-choice. Frequently attending religious services was associated with a decreased odds of being pro-choice. People who thought liberalising abortion law would increase maternal mortality had a 50% lower odds of being pro-choice than people who thought that liberalising the law would decrease maternal mortality.

Support for specific grounds for abortion

Support for legalisation of abortion on specific grounds varied greatly (data not shown). A majority of participants believed that abortion should be legal when the woman’s life is at risk (82%), the woman’s health is at risk (76%), the pregnancy results from rape (64%) or there is a risk of fetal impairment (53%). Far fewer respondents supported legal abortion when the woman is a minor (21%), for economic reasons (17%), when the woman is single (11%) or when pregnancy occurs because of contraceptive failure (11%). Of note is that a large percentage expressed support for abortion when asked about specific circumstances, even among those who, when asked initially for a general opinion, said abortion should be illegal in all circumstances. For example, 42% of those with an initial anti-choice stance supported legal abortion when the woman’s life is at risk when probed by circumstance. Similarly, 36% with initial anti-choice views subsequently supported legal abortion when the woman’s health is in danger.

Respondents appeared to support legal abortion more in circumstances which they perceived as outside a woman’s control (i.e. when the health or life of the woman is at risk) versus circumstances that arguably are within the woman’s control (i.e. contraceptive failure). These findings may reflect not only beliefs about abortion law but also prevailing views on women’s sexuality. When asked in a closed-ended, multiple-choice question what they felt was the main reason Mexican women seek abortions, the highest percentage of respondents (33%) answered that women “lacked responsibility”. According to a leading Mexican anthropologist, it is precisely this type of judgmental stance that implicitly blames women for becoming pregnant, reinforces a culture of clandestine abortion, contributes to the mental anguish some women experience when seeking abortions and keeps abortion largely illegal.Citation30

Our results generally agree with those of previous surveys.Citation31 Nationally representative surveys from the early 1990s found Mexican women more conservative than men and people in the lowest socio-economic categories more conservative than those in the highest.Citation20 Earlier surveys also found greater support for abortion in circumstances such as risk to the health or life of the woman than for socio-economic reasons or contraceptive failure.Citation20

Public provision versus private condemnation

The predominant religion in Mexico is Roman Catholicism. As shown in and , Mexicans who attended religious services at least once a week had a lower odds of having correct information about abortion laws and were more likely to hold anti-choice views than less religious or non-religious people. These results may be explained, in part, by the Church’s unequivocal anti-choice stance and its role as a major influence in many people’s lives. The Church not only proclaims its stance in church services but has actively participated in public debate on abortion, with the intention of influencing Mexican politics, public opinion and legislation.Citation18, Citation32, Citation33

Despite fervent efforts by the Catholic church, 79% of people who identified as Catholic felt that abortion should be legal in some cases. In addition, 80% of Catholics believed that all public health institutions and hospitals should have the capacity to provide legal abortions, and 80% of all respondents were opposed to Mexican legislators voting on abortion laws based on their personal religious beliefs.

At the same time, less than half (45%) agreed either totally or partially with the statement: “At times, an induced abortion is the best option in a difficult situation.” Similarly, in response to an open-ended question, less than a third (31%) said they would advise “a close family member who became pregnant as a result of rape and who did not want to continue the pregnancy” to seek a legal abortion.

The apparent conflict between these opinions may reflect two prominent but conflicting forces in Mexican culture and society. Mexicans have been socialised to believe in the legal separation of church and state, despite the power of the Church,Citation34 and they also support free or low-cost government health services. Thus, while most participants supported structures to provide government-funded abortions in cases when abortion is legal, some still rejected abortion socially and personally, even in cases of rape.

Implications

Since our data are cross-sectional, we cannot determine the causal relationships between the variables in our analysis; however, the associations uncovered may be helpful in shaping the strategies of pro-choice advocates in Mexico.

First, greater efforts need to be made to ensure that all Mexicans know that they have a legal right to abortion in some circumstances, and that they know the procedures necessary for obtaining a legal abortion if required. Conveying this information is important in itself, but given that those who knew abortion is sometimes legal in their state tended to have more liberal views suggests that knowing that abortion is legal might also help to make it more acceptable. Second, part of the reason some people are against liberalising abortion law may be because they think it will increase maternal mortality. Hence, informing the public that abortions are much safer if they are legal might be another key strategy to liberalise public opinion and pave the road to an expanded range of circumstances in which abortions are legally available. However, it is important to recognise that Mexico’s current abortion laws only allow for legal abortions in limited circumstances, and these are not the circumstances for which most Mexican women seek abortions.

Social and cultural factors continue to shape public opinion. Thus, there was an unwillingness to state a personal acceptance of abortion, since this goes against social norms. However, sociologists have argued that growing support for secularisation is reflected in public opinion.Citation35 Since most of our Catholic-identified respondents believed that the Church and personal religious beliefs of legislators should not factor into abortion legislation, and most Mexicans reject (at least, in theory) the right of the Church to participate in politics, supporters of legal abortion should highlight the Church’s continual and blatant breach of this separation in order to rally public opposition to such activities.

Our results also suggest the presence of judgmental social views of women who seek abortions, legal or otherwise, as “irresponsible” sexually and a Catholic morality of sin and shame in relation to women’s sexuality and abortion.Citation30 To improve access to abortion in Mexico, pro-choice advocates will need to use a variety of strategies that acknowledge the beliefs of the Mexican population and at the same time, seek to reduce the stigma associated with sexuality and therefore of women’s need for abortion.

Finally, because a majority of Mexicans favour government-provided health services, the Mexican public is more likely to champion women’s access to abortion if they view it as a legal right and a right to public services, as witnessed by the response to the Paulina case. Efforts to increase access to safe, legal abortions in Mexico might frame the issue by informing the public that although abortion is legal in certain circumstances, a difficult process prevents women’s access to these services,Citation11 and call for training of more health care providers to offer safe and accessible abortion services.

Acknowledgements

We wish to thank Grupo IDM in Mexico City for its assistance in carrying out fieldwork and data entry, as well as the many women and men who participated in our survey. We are also grateful to several Mexican, Latin American and US colleagues for their helpful comments on the study instruments and methodology. This project was supported by the John D and Catherine T MacArthur Foundation and David and Lucille Packard Foundation.

Notes

* Regions reflect the areas used in Nielsen media ratings research in Mexico.

* The seven states not included in the sample were Baja California Sur, Campeche, Chihuahua, Colima, Durango, Morelos and Quintana Roo.

References

- World Health Organization. Unsafe Abortion: Global and Regional Estimates of the Incidence of Unsafe Abortion and Associated Mortality in 2000. 4th ed, 2004; WHO: Geneva.

- OA Ladipo. Preventing and managing complications of induced abortion in Third World countries International Journal of Gynecology and Obstetrics. 3(Suppl.): 1989; 21–28.

- J Paxman, A Rizo, L Brown. The clandestine epidemic: the practice of unsafe abortion in Latin America Studies in Family Planning. 24(4): 1993; 205–226.

- E Áhman, I Shah. Unsafe abortion: worldwide estimates for 2000 Reproductive Health Matters. 10(19): 2002; 13–17.

- B Ganatra, HB Johnston. Reducing abortion-related mortality in South Asia: a review of constraints and a road map for change Journal of American Medical Women’s Association. 57(3): 2002; 159–164.

- M Berer. Making abortions safe: a matter of good public health policy and practice Reproductive Health Matters. 10(19): 2002; 31–44.

- CONAPO. Cuadernos de salud reproductiva — República Mexicana. 2000; CONAPO: México DF.

- WHO. Abortion: A Tabulation of Available Data on the Frequency and Mortality of Maternal Health and Unsafe Abortion. 1994; WHO: Geneva.

- Grupo de Información en Reproducción Elegida (GIRE). Miradas sobre el Aborto. 2000; METIS, Productos Culturales, S.A. de CV: México DF.

- A Rahman, L Katzive, SK Henshaw. A global review of laws on induced abortion, 1985—1997 International Family Planning Perspectives. 24(2): 1999; 56–64.

- D Lara, S Garcia, J Strickler. El acceso al aborto legal de las mujeres embarazadas por violación en la ciudad de México Gaceta Médica de México. 139(S1): 2003; S77–S90.

- E Barraza. Aborto y Pena en México. 2003; Instituto Nacional de Ciencias Penales: México DF.

- E Poniatowska. Las mil y una… (la herida de Paulina). 2000; Plaza Janés Editores, SA: Barcelona.

- GIRE. Paulina: In the name of the law. 2001; GIRE: México DF.

- R Taracena. Social actors and discourse on abortion in the Mexican press: the Paulina case Reproductive Health Matters. 10(19): 2002; 103–110.

- Magally S. En vigor, las reformas al Código Penal en el DF sobre aborto. Comunicación e información de la mujer (CIMAC). 2000 Sep 25. At: http://www.cimac.org.mx/noticias/00sep/00092501.html. Accessed 14 April 2003.

- Asamblea Legislativa del Distrito Federal. Decreto por el que se reforman y adicionan diversas disposiciones del código de procedimientos penales para el Distrito Federal Gaceta Oficial del Distrito Federal, México 148: 2000; 2–3.

- M Lamas, BS Bissell. Abortion and politics in Mexico: “Context is all” Reproductive Health Matters. 8(16): 2000; 10–23.

- J Klesner. Democratic transition? The 1997 Mexican elections Political Science and Politics. 30(4): 1997; 703–711.

- S Pick de Weiss. Resultado de tres encuestas nacionales de opinión sobre el aborto, México 1991—1993 Encuentro de Investigadores sobre Aborto Inducido en América Latina y el Caribe, parte 2. 1994; Universidad Externado de Colombia: Bogotá, 85–103.

- GIRE. Análysis de Resultados de Comunicación y de Opinión Pública. Estudio de opinión pública sobre aborto en el Distrito Federal. Apr. 1999

- Estadástica Aplicada. Estudio de Opinión sobre el Aborto en el Estado de Guanajuato. Aug. 2000

- LL Bumpass. The measurement of public opinion on abortion: the effects of survey design Family Planning Perspectives. 29(4): 1997; 177–180.

- Cook EA, Jelen TG, Wilcox C. Measuring public attitudes on abortion: methodological and substantive considerations. Family Planning Perspectives. 1993; 25 (3): 118.—21, 145.

- JM Converse, S Presser. Survey questions: handcrafting the standardized questionnaire Quantitative Applications in the Social Sciences. 1986; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA.

- Centro de Estudios de Opinión, Universidad de Guadalajara. Estudio para conocer la percepción de la población del Estado de Guanajuato sobre la penalización de la práctica del aborto. Aug 2000

- M Diego. Preguntas inducidas, en el sondeo sobre el aborto en Guanajuato La Jornada. 2000 Aug 22 Sect. Polática:15

- Conteo de Población y Vivienda, INEGI, 1995.

- DW Hosmer, S Lemeshow. Applied Logistic Regression. 1989; John Wiley and Sons: New York.

- A Amuchástegui Herrera, M Rivas Zivy. Clandestine abortion in Mexico: a question of mental as well as physical health Reproductive Health Matters. 10(19): 2002; 95–102.

- S Cohen. Encuestas de opinión pública sobre el aborto en México. A Ortiz Ortega. Razones y Pasiones en Torno al Aborto. 1994; Population Council: Mexico City, 112–115.

- Culler TA. Paper justice. Conscience 2000; 21(2): 16.—18, 27.

- Mexican authorities warn Roman Catholic priests to avoid political involvement following complaint by abortion-rights supporting party Kaiser Reports. 2003 Aug 20 At: http://www.kaisernetwork.org/daily_reports/rep_index.cfm?hint=2&DR_ID=19446. Accessed 10 September 2003

- RA Camp. The cross in the polling booth: religion, politics, and the laity in Mexico Latin American Research Review. 29(3): 1994; 69–100.

- R Blancarte. El Papel de la Religión en México. Un informe de Religion Counts. 2003; Park Ridge Center: Washington, DC.