Abstract

In 2002 Nepal’s parliament passed a liberal abortion law, after nearly three decades of reform efforts. This paper reviews the history of the movement for reform and the combination of factors that contributed to its success. These include sustained advocacy for reform; the dissemination of knowledge, information and evidence; adoption of the reform agenda by the public sector and its leadership in involving other stakeholders; the existence of work for safe motherhood as the context in which the initiative could gain support; an active women’s rights movement and support from international and multilateral organisations; sustained involvement of local NGOs, civil society and professional organisations; the involvement of journalists and the media; the absence of significant opposition; courageous government officials and an enabling democratic political system. The overriding rationale for reforming the abortion law in Nepal has been to ensure safe motherhood and women’s rights. The first government abortion services officially began in March 2004 at the Maternity Hospital in Kathmandu; services will be expanded gradually to other public and private hospitals and private clinics in the coming years.

Résumé

En 2002, le Parlement népalais a adopté une législation libérale sur l’avortement, après presque 30 ans d’efforts. Cet article retrace l’histoire du mouvement de réforme et répertorie les facteurs qui ont contribuéàson succès : un plaidoyer soutenu pour la réforme ; la diffusion de connaissances et d’informations ; l’adoption du calendrier de réforme par le secteur public qui a dirigé les activités pour recruter d’autres partenaires ; l’existence de projets pour une maternité sans risque comme contexte dans lequel l’initiative a pu gagner des appuis ; un mouvement actif pour les droits des femmes, et le soutien d’organisations internationales et multilatérales ; la participation d’ONG locales, de la société civile et d’organisations professionnelles ; le concours de journalistes et des médias ; l’absence d’opposition notable; de courageux fonctionnaires et un système politique démocratique autorisant le changement. La justification de la réforme était de garantir une maternité sans risque et de protéger les droits des femmes. Les premiers services publics d’avortement ont officiellement ouvert en mars 2004àla Maternité de Katmandou et ils seront progressivement étendus ces prochaines annéesàd’autres hÁpitaux publics et privés etàdes dispensaires privés.

Resumen

En el 2002, el parlamento de Nepal aprobó una ley de aborto liberal, después de casi tres décadas de esfuerzos para lograr reformas. En este artáculo se revisa la historia del movimiento de reforma y la combinación de factores que contribuyeron a su éxito. Entre estos figuran: la continua gestoráa y defensa de la reforma; la difusión de conocimientos, información y pruebas; la adopción de la agenda de reforma por parte del sector público y su liderazgo para hacer partácipe a otras partes interesadas; las actividades promotoras de la maternidad sin riesgos como el contexto en que la iniciativa podráa ganar apoyo; un movimiento activo de los derechos de las mujeres y el apoyo de organizaciones internacionales y multilaterales; la participación sostenida de las ONG locales, la sociedad civil y las organizaciones profesionales; la participación de los periodistas y los medios de comunicación; la ausencia de una oposición significativa; funcionarios gubernamentales valientes y un sistema polático democrático favorable. La justificación principal para reformar la ley de aborto en Nepal ha sido el garantizar la maternidad sin riesgos y los derechos de las mujeres. Los primeros servicios gubernamentales de aborto se iniciaron oficialmente en marzo de 2004 en el Hospital de Maternidad de Katmandú y, en los próximos años, éstos se ampliarán gradualmente a otros hospitales, públicos y privados, y a clánicas privadas.

On 14 March 2002, the national parliament of Nepal passed a bill (Muluki Ain 11th Amendment Bill) which amended various sections of the Muluki Ain (national Legal Code) of 1963, effectively liberalising the very strict, decades-old abortion law. Subsequently, in 2004, the bill became law. The road to reform of the abortion law was a long one, characterised by periods of both low and high intensity of effort in both the public and private spheres. This article reviews the history of the reform process and the synergistic combination of factors that contributed to the reform.

Nepal’s abortion law before 2002

Until this latest reform, abortion in Nepal was prohibited by the Muluki Ain. Citation1, Citation2 Based on ancient Hindu scriptures, traditions and practices,Citation3 the Muluki Ain was first introduced in 1854, then amended several times and extensively revised in 1963. It did not permit the termination of pregnancies even if they were the result of rape or incest or threatened the woman’s life. In effect, it equated abortion with infanticide, and infanticide with other kinds of murder or homicide, and did not recognise any mitigating factors or exceptional circumstances under which abortion was not a crime of murder. Physicians and other medical practitioners were prohibited from recommending or performing abortion without exception.

In this environment, women who sought abortions and providers who provided abortion necessarily did so clandestinely. Most of the abortions that took place were unsafe according to the WHO definition.Citation4 Only a very small proportion of women, mostly those living in urban or semi-urban areas and able to afford the cost, had access to trained medical practitioners and safe procedures.Citation5

The harsh provisions of the old law contributed to a recurring situation in which an induced abortion, and sometimes even a spontaneous abortion, would be deliberately misclassified as a crime of infanticide, willful killing or murder, in order to have a woman convicted and incarcerated, so that she would lose her rights to any family property. A number of studies of women imprisoned for abortion Citation6 Citation7 Citation8 have shown that police and prosecutors pressed charges for murder, homicide or willful killing because they carried a much stiffer penalty — as high as life imprisonment. In these cases, the law did not clearly distinguish between abortion and murder. Often, these injustices were perpetrated by greedy in-laws working in collusion with litigators and others connected with the courts, so that the family would not have to share land or other property with the hapless woman. Indeed, many women prosecuted under the old law were still behind barsCitation6 until November 2004, when the King of Nepal granted the first amnesty.

Abortion as part of fertility control

Efforts to liberalise the abortion law in Nepal began in the 1970s. An early catalytic event was a high-level conference in 1974, organised by the Family Planning Association of Nepal (FPAN), an affiliate of the International Planned Parenthood Federation and the largest non-governmental organisation (NGO) in the health sector. The conference brought together programme managers, providers and policymakers representing the public and private sectors to discuss the medical rationale and relevance of making abortion legally accessible and available to women with unwanted pregnancies. This was followed in the same year by a regional seminar, jointly organised by the FPAN and the Transnational Family Research Program of the American Institutes for Research, which reviewed the current status of abortion and related research in the region and discussed the implications for Nepal. These meetings underscored the fact that the law was too restrictive and that some liberalisation was desirable in the interest of women’s health and well-being. These meetings served as the springboard for subsequent reform-oriented activities.

Still other initiatives by the Nepal Law Commission,Citation9 a government body responsible for reviewing and recommending timely changes in existing laws, and the Institute of Law,Citation10 the national university’s school of law, led the Law Reform CommissionCitation11 to recommend that existing abortion-related law be reformed and liberalised. The 1970s was also a time when the government of Nepal, with assistance from the US, initiated two national level, consensus-building conferences on the need to regulate population growth through maternal and child health programmes. Central to this was the implementation of a national family planning programme, which had already been set up by the FPAN. Citation12, Citation13 In both conferences, the role of abortion as an effective method of regulating fertility was also discussed. Later, the National Commission on Population recommended to the government that abortion be made legal for pregnancies resulting from contraceptive failure.Citation11 Thus, in the 1970s abortion was discussed largely as a means to control fertility and not as a matter of maternal health or rights, as would become the case in subsequent decades.

Activities to develop a broader consensus for reform continued in the ensuing years. In the mid-1980s, prominent justices, judicial administrators, legal and administrative authorities, law professionals, social workers and social scientists addressed the abortion issue in a national forum organised by the Nepal Women’s Organization (NWO), the only officially-recognised women’s organisation prior to 1990. Subsequently, NWO convened a meeting of prominent jurists to examine the legal status of abortion and make concrete recommendations for reform. Citation14 The consensus from both these forums was that abortion should be made legal and available in cases of pregnancy resulting from rape or incest or where the woman’s life may be at risk. However, none of the recommendations were taken up by the national legislature, probably because the issue was considered too sensitive and the movement did not yet have the momentum or popular support to push the legislature into action.

A contributing factor to this situation was the change in the mid-1980s in US policy on abortion, when the Mexico City Policy (the first Global Gag RuleFootnote*) was first implemented.Citation15 The Nepal government may have been discouraged from supporting the reform movement, given that the US government was a key donor to Nepal’s health and family planning programmes.

Safe abortion as part of safe motherhood

The movement to reform the abortion law took on a different dimension in the early 1990s, when Nepal became involved in the international Safe Motherhood initiative launched by WHO in 1987. In 1993, the Family Health Division, Nepalese Ministry of Health, took responsibility for developing a Safe Motherhood policy and plan of action, as an integral part of the National Health Policy, with technical support primarily from WHO.Citation16 This involved compiling and reviewing evidence, bringing together key providers, international and national organisations, raising awareness and eventually preparing a framework for a programme plan for 1994—97. Citation17, Citation18 The 1994 International Conference on Population and Development (ICPD) and the 1995 Beijing Conference on Women, where Nepal was a co-signatory to both declarations, also provided international impetus and greater legitimacy to the women’s rights movement that was beginning to gain momentum in Nepal. Availability of and access to safe abortion services increasingly began to be understood in the context of women’s rights.

On the service delivery side, in mid-1995 a new, safer and relatively inexpensive technology, manual vacuum aspiration (MVA), was introduced in Nepal’s largest maternity hospital in Kathmandu for treating incomplete abortions. Citation19, Citation20 This initiative is still being expanded to other hospitals in and outside the Kathmandu Valley, to reduce morbidity from clandestine and unsafe abortion. The introduction and expansion of MVA use helped to bring abortion-related issues to the forefront of maternal health service delivery in the country.

An important advance was the formation of the Safe Motherhood Network in early 1997. Its main purpose was to provide continued momentum to Safe Motherhood-related issues by involving the government, NGOs and other private sector organisations. Today it has established a presence in most districts, and currently has over 160 local organisations throughout the country. The Network is managed by a private consulting group, SAMANATA. It organises awareness-raising and advocacy activities at the community level, facilitates media coverage of Safe Motherhood issues and promotes dialogue among policymakers, service providers and journalists, thereby contributing to the reform momentum.

The mid-1990s also saw the implementation of a fairly large-scale government programme focusing exclusively on Safe Motherhood in several districts,Citation21 which has been expanded to 10 districts of the country with funding from the UK. Citation22 However, the actual reduction in mortality due to this intervention remains unknown. A related activity, whose impact also remains unknown, was an undertaking by the Ministry of Health in the mid-1990s to develop guidelines for maternal health care services, with the objective of helping to improve quality of care.Citation23

Up to this point, the Ministry of Health had not been actively involved in any effort to reform the existing law. Its involvement in Safe Motherhood work led the Ministry to help to build consensus and political commitment around the reform effort, and bring on board other relevant government entities, such as the Law Reform Commission and the Ministry of Education. Furthermore, it helped galvanise the support of other civil society institutions working in law and health, by involving them in meetings and workshops and receiving their inputs verbally or in writing. Eventually, a paper outlining a Safe Motherhood policy and work plan was prepared and adopted by the Ministry.Citation24, Citation25 An important element in it was the liberalisation of the existing abortion law, to reduce the high levels of maternal mortality and morbidity from unsafe abortions in the country. Thus, reform was placed in the larger context of saving women’s lives and helping to reduce maternal deaths and morbidity as part of an international movement. Second, and very importantly, long-standing reform efforts in the form of awareness-raising meetings and conferences and recommendations emanating mainly from the NGO sector had found a legitimising partner in the government sector.

Alongside the Safe Motherhood policy were efforts to educate legislators and other stakeholders regarding the plight of Nepalese women and the feasibility and necessity of improving their status and conditions through policy, legislative and programmatic interventions. In this connection, several workshops were organised for policymakers, legislators, international and national NGOs engaged in the health sector, citizens groups, physicians, nurses and the media. A relatively recent example of this was a symposium jointly organised in January 1996 by the Population and Social Committee of the National Parliament, Nepal Medical Association, Nepal Society of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (NESOG) and the FPAN. The participants endorsed the view that “while unrestricted abortion was neither desirable nor right for Nepal, abortion for first trimester pregnancies should be made legal, if performed by registered and trained medical practitioners”.Citation26

Democratic changes in national governance

Another important development around this time was the change in the political system of the country. Monarchical rule gave way to a constitutional monarchy in 1990. Citation27, Citation28 By the following year, the country had a democratically elected government. Political reform paved the way for a larger role for many stakeholders in the nation’s well-being, giving them a stronger voice in the legislative system and in governance. People developed new enthusiasm and expectations. Without this, it is doubtful that the level and quality of leadership shown by the government and its ability to effect change would have taken place. In 1993 the US discarded the Mexico City Policy, thereby contributing to a more liberal and enabling policy environment in Nepal, which also affected the abortion law reform movement.

With the restoration of democracy in 1990, literally hundreds of NGOs seeking a role in the social change process had sprung up across the country. The 1990s also witnessed intensified campaigns in the international arena for women’s rights, including reproductive rights, and for the elimination of discrimination against women, epitomised in the 1994 ICPD and the 1995 Beijing conferences.

Before 1990, the government strictly controlled NGOs and the mass media. In this new environment, many women’s rights groups emerged and could network with national and international organisations with similar goals. Lobbying groups were organised and the women of Nepal began making their voices heard in meetings, conferences, delegations, demonstrations and the media. Over time, the women’s groups grew stronger and more effective in putting pressure on the government to protect and promote many rights for women.Citation29

Reproductive rights, including the right to safe abortion, and human rights together provided yet another dimension to the rationale for reform of the abortion law. Given these developments, the government established in 1995 the Ministry of Women and Social Welfare (subsequently renamed Ministry of Women, Children and Social Welfare).

It should be noted that the absence of any significant opposition to the movement for abortion law reform was as important as overt support. In fact, there was never much organised opposition to the reform movement, either from the public or the private sector, even though, at the same time, there was no strong, consistent or massive support in its favour. One reason for the lack of opposition may have been limited resources, external or internal, for campaigning against what was a slow but gradual movement toward reform. Another reason may be that abortion had become relatively acceptable in Nepal because it had already been legalised for many years in neighbouring India, the world’s largest democracy and undoubtedly a major source of influence for Nepal — culturally, politically and otherwise. Arguably, had abortion not already been accepted in India, where as in Nepal a huge segment of the population is Hindu, advocates may have found the going tougher and been forced to be more cautious in pressing for change.

Evidence of the public health consequences of unsafe abortion

An important factor in promoting reform was empirical evidence from well-conducted studies, which was synthesised and disseminated to stakeholder groups. Much of the Nepal-specific information had remained largely unknown or undisseminated until the early 1980s, when the situation began to change. In 1984 a benchmark study was carried out in five hospitals in and around Kathmandu, the capital.Citation30, Citation31 The study examined all cases of women hospitalised due to complications of induced abortion over a period of one year. The study confirmed what had already been suspected, that even in urban areas many abortion service providers were untrained and unaware of the unsafe and sometimes fatal manner in which they practised. The study found that as high as 50% of all maternal deaths in the study hospitals were due to abortion-related complications.

Another study, in 1985 in seven rural districts of Nepal, Citation32, Citation33 included data from community-based surveillance, providers of abortion services and hospitals. Information on induced and possibly induced abortions was obtained on a total of 13,229 women of reproductive age (15—49) in these communities. The study found that most women seeking abortion and the providers of abortion were aware that abortion was illegal and carried heavy penalties. The primary reason for seeking abortion reported by the majority of women in this study, just as in the urban study the year before, was economic hardship, largely due to too many children. Traditional birth attendants (TBAs) were reported to be the primary source of abortion services for a significant proportion of women in the rural communities.

In 1992—94, a six-month prospective studyCitation34 was carried out in four public hospitals and one private clinic in Kathmandu. This study confirmed many of the findings of the first urban-based study ten years before, that although post-abortion contraceptive use was high, many women sought repeat abortions due to method failure and other factors.

Studies of women in prison published in 1982 and 1989, Citation8, Citation14 and others in 2000 and 2002, Citation6, Citation7 showed that at least one-fifth of women in prison had been convicted for illegal abortion and others were serving jail sentences for crimes they had not committed, while many had been charged with murder. These findings added human rights, welfare, social justice and equal-treatment-under-the-law dimensions to the arguments for abortion law reform. Thus, the rationale for reform ceased to rest solely on health or medical grounds. With the more recent case studies, the reform movement began to attract the attention and support not only of law professionals and women’s groups but also human rights activists and social justice groups, among others.

From the early 1990s, collecting data on maternal deaths became a priority of the Ministry of Health. The oft-cited maternal mortality ratio of 539 per 100,000 live births, the average for the 1990—96 period, was based on the 1996 national Demographic and Health Survey.Citation35 Another study on maternal morbidity and mortality was carried out in 1996—97 in three districts of the country, Citation36 but the number of abortion-related deaths was not reported. Even so, these studies helped to paint a picture over the years of the extent and consequences of unsafe abortion. The results and their implications for policy and programming were disseminated in user-friendly forms by the Ministry of Health, NGOs and researchers in various forums, such as the annual meetings of the Nepal Medical Association, NESOG and FPAN and published in local newspapers and magazines.

The role of the media

The role of the media, planned and unanticipated, in the process of ushering in reform should not be underestimated. In the wake of the new constitution,Citation37 the 1990s saw rapid development and change in Nepal’s media,Citation38, Citation39 including an increasing role for the private and commercial sectors in broadening access to information of all kinds, including via the Internet for those in urban centres. Commercial FM radio stations were established, something unthinkable in prior years. Soon there were several dozen, mostly foreign, television channels and cinemas, which until 1990 had been under strict state control and were deregulated. Furthermore, there were no longer restrictions on the use of personal dish antennas to receive domestic or foreign television broadcasts. The number of newspapers in Nepal almost doubled during the first half of the 1990s — from 528 in 1990—91 to 1,006 in 1995—96.

Freedom of the press and deregulation allowed the media to play a critical role in the diffusion of information on women’s rights and abortion among many other issues. Journalists were centrally involved in these tasks.

Introduction of two bills on abortion in the Parliament

The democratisation of the political system in Nepal made it possible for members of Parliament to introduce private bills. The President of the FPAN, who was also a member of the National Assembly, the upper house of Parliament, introduced a private bill in its 1996 Spring (10th) Session. Although the bill was about liberalisation of the abortion law, it was called the “Pregnancy Protection Bill” and its aim was described as protecting wanted pregnancies.Citation40 This reflects the climate of ambivalence and uncertainty in which the bill was put forward.

This first bill was debated several times by the National Assembly’s Special Committee over a one-year period, but it did not make much headway toward a final vote due to the expiration of the term of office of the bill’s sponsor. As a result, it was rendered null and void. If it accomplished nothing else, however, it helped to direct the attention of legislators to the issue of abortion and increased the impetus to put forward a government-sponsored reform bill several months later.

The then director of the Ministry of Health’s Family Health Division, who had also spearheaded the government’s Safe Motherhood programme, was a charismatic and committed person. Similarly, the Secretary of the Law Reform Commission was an influential member of the Technical Committee of the Safe Motherhood programme whose input to the drafting of the bill proved essential to its viability. Technical guidance and commitment on the part of senior officials within the Ministry of Health also proved to be essential in the overall process, along with international evidence on “best practices”.Citation41

The Ministry of Law, Justice and Parliamentary Affairs brought before Parliament the Muluki Ain 11th Amendment Bill, 1997 which included extensive amendments to the Legal Code in the section on abortion and a number of other amendments aimed at removing gender-based discrimination in provisions on inheritance of property, citizenship, divorce and marriage, and increasing the punishments for rape, particularly for rape of minors, pregnant and disabled women. Citation42 Many components of the Bill were hotly debated on many occasions both inside and outside Parliament. One such debate, a seminar in March 2000, revealed a serious lack of consensus on several of the amendments among the lawmakers, women’s rights activists and other legal experts who participated, even among lawmakers in the same political party.Citation43 The lack of consensus was stronger with regard to property rights than any other aspects of the Bill, however, including abortion.

The all-or-nothing strategy of achieving a comprehensive change in the Legal Code through a single Bill proved to be successful in the end, although it was not without serious risks and disadvantages. One such disadvantage was that the entire Bill remained bogged down in controversy on some of the more sensitive provisions, which arguably warranted constitutional amendments. The Bill was initially approved by the House of Representatives in October 2001, but rejected by the National Assembly due to continuing disagreements over women’s property rights. There was a deadlock and zero progress for a period of time but supporters knew that its passage meant the passage of all of the amendments proposed, including on abortion.

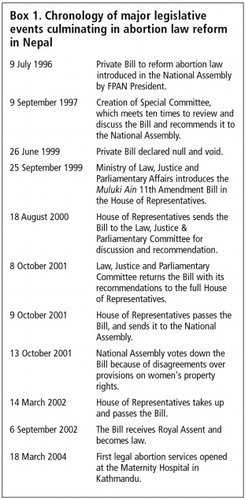

In March 2002 the 21st session of the 205-member House of Representatives reconsidered the Bill and passed it. The vote in favour was 147 of the 148 members in attendance. This was a profound victory for the women of Nepal and for the various public and private NGOs and other stakeholders actively involved in the reform movement. Publicly, it was viewed as evidence of the sensitivity and responsiveness of the popularly elected government towards issues of gender equity and equality and women’s property rights. Box 1 summarises the major parliamentary events leading to the success of the reform.

The new abortion law provisions

As amended the Legal Code grants the right to termination of pregnancy to all women without regard to their past or present marital status, on the following grounds and with one important exception:Citation42

| • | The right to terminate a pregnancy of up to 12 weeks voluntarily. | ||||

| • | The right to terminate a pregnancy of up to 18 weeks if the pregnancy is due to rape or incest. | ||||

| • | The right to seek abortion upon the advice of a medical practitioner at any time during a pregnancy if the pregnancy poses a danger to the woman’s life or her physical or mental health, or in cases of fetal abnormality or impairment. | ||||

| • | Abortion on the basis of sex selection is prohibited. Amniocentesis is prohibited for purposes of sex determination for abortion. Anyone found guilty of conducting or causing to be conducted such an amniocentesis test is to be punished with imprisonment of 3—6 months. Anyone found guilty of performing or causing to be performed an abortion on the basis of sex selection is to be punished with one additional year of imprisonment. | ||||

In September 2002, the Bill was given the Royal Assent by the King, and the Ministries of Health and Justice, Law and Parliamentary Affairs took the leadership in preparing rules and regulations for implementation of the law.Citation44 The task included definition and specifications of providers, techniques and procedures; assurance of minimum quality of services; and a legal framework for service delivery. One of the main underlying premises that was recognised in this process was that any barriers to women’s access to safe abortion services would drive women to have unsafe procedures.

The regulations specify that for pregnancy up to 12 weeks MVA can be used, while beyond 12 weeks, MVA and dilatation and evacuation (D&E) can be used.Citation44 Citation45 Citation46 A health care institution or provider wishing to provide abortion needs to be registered with the Ministry of Health’s Department of Health Services. A provider is defined as a trained medical practitioner or health worker. They are permitted to charge for the cost of pregnancy termination, but are required to maintain transparency about price.

A comprehensive abortion service was planned, to be implemented in two stages.Citation46 In the first stage, only physicians would be trained to provide services. In the second stage, staff nurses would be trained to provide abortions up to six weeks of pregnancy without the presence of a trained physician. The referral network with regard to the public health system is presumed to exist and be functioning. Private clinics providing services are expected to show evidence of referral links with private hospitals able to offer appropriate care. The overall goal is “to reduce maternal morbidity and mortality due to unsafe abortions”, Citation47 consistent with the Safe Motherhood policy and programme developed in the 1990s.

The first government abortion services officially began on 18 March 2004 at the Maternity Hospital in Kathmandu.

Conclusion

The parliamentary process in the Parliament from introduction to final passage of the Muluki Ain 11th Amendment Bill and the assent of the King took about four years. The development of operational policies, regulations and guidelines took another six months. Nepal’s experience suggests that the process of bringing about abortion law reform can be complex and lengthy. Overall, the road to abortion law reform in Nepal turned out to be nearly three decades long.

The overriding rationale for reforming the abortion law in Nepal has been to ensure safe motherhood and women’s rights. In this context, high quality family planning servicesCitation48, Citation49 should go hand-in-hand with safe abortion services.

Reforming the law was an important and necessary step, and implementing the law effectively is an equally important next step. In the case of Nepal, indications are that the Ministry of Health, which has the primary responsibility, is proceeding systematically. It will take some years for the provisions of the amended abortion law to become widely known and fully implemented, especially for women in rural and remote areas of the country. Moreover, the social and legal systems, the customs and practices that have evolved over a long time under the old law, will take time to change too. Although some women have received an amnesty, it also remains to be seen whether the remaining women languishing in Nepalese jails on charges to do with abortion will all be released and not be replaced by others. The plight of the women in prison should not be allowed to be overshadowed by the success of the reform, even if the new law is not retroactive.

Note

The views expressed are solely those of the author. No financial or institutional support was received.

Notes

* This policy restricted non-US NGOs that receive US family planning funds from using any funds to provide legal abortion services, lobby their own governments for abortion law reform, or provide counselling or referrals for abortion.

References

- Ministry of Law and Justice. Muluki Ain, 2020 (Legal Code, 1963). 1963; Ministry of Law and Justice: Kathmandu.

- GB Shrestha. Muluki Ain: Yek Tippani (Muluki Ain: A Commentary). 7th edition, 2002; Pairavi Prakashan: Kathmandu.

- A Hoefer. The Caste Hierarchy and the State in Nepal: A Study of the Muluki Ain of 1854. 1979; Universitatsverslag Wagner: Innsbruck.

- World Health Organization. Prevention and Management of Unsafe Abortion: Report of a Technical Working Group. 1993; WHO: Geneva.

- S Thapa, S Padhye. Induced abortion in urban Nepal International Family Planning Perspectives. 27: 2001; 144–147.

- Center for Reproductive Law and Policy and Forum for Women, Law and Development. Abortion in Nepal: Women Imprisoned. 2002; CRLP: New York.

- Center for Research on Environment and Population Activities. Women in Prison in Nepal for Abortion: A Study on Implications of Restrictive Abortion Law on Women’s Social Status and Health. 2000; CREHPA: Kathmandu.

- Integrated Development Systems. Women in Prison: Case Studies. Study Report. 1982; IDS: Kathmandu.

- Nepal Law Commission. Nepal Law Commission Report, 1973. 1973; Nepal Law Commission: Kathmandu.

- Institute of Law. Report on Law and Population Growth in Nepal. 1979; Institute of Law: Kathmandu.

- Law Reform Commission. Law Reform Commission Report, 1982. 1982; Law Reform Commission: Kathmandu.

- Conference on the Implementation of Population Policies. A collection of papers presented at the conference sponsored by the Population Policies Coordination Board, Nepal, Ministry of Health, Nepal, and University of California, Berkeley, FP/MCH Project in Nepal, 3—6 August 1976. 1976; FP/MCH Project: Kathmandu.

- Workshop-Conference on Population, Family Planning, and Development in Nepal. A collection of papers presented at the conference sponsored by HIS Majesty’s Government of Nepal; Family Planning/Maternal and Child Health Project, Nepal; University of California Family Planning/Maternal and Child Health Project, Berkeley, 24—29 August 1975. 1975; FP/MCH Project: Kathmandu.

- Nepal Women’s Organization. [Female Inmates in the Prisons of Nepal: A Report on the Study of Status and Problems of Women Prisoners]. 1989; Nepal Women’s Organization: Kathmandu(In Nepali)

- Population Action International. What You Need to Know about the Global Gag Rule Restrictions: An Unofficial Guide. 2001; PAI: Washington DC.

- Ministry of Health. National Health Policy. 1991; Ministry of Health: Kathmandu.

- Ministry of Health. Safe Motherhood Program in Nepal: A National Plan of Action, 1994—1997. 1993; Department of Health Services, Family Health Division, Ministry of Health: Kathmandu.

- Ministry of Health. National Safe Motherhood Plan, July 2002—July 2017. Final Draft. 2002; Department of Health Services, Family Health Division, Ministry of Health: Kathmandu.

- K Malla, S Kishore, S Padhye. Establishing Postabortion Care Services in Nepal. JHPIEGO Technical Report. 1996; JHPIEGO: Baltimore.

- Thapa S, Poudel J, Padhye S. Triaging patients with postabortion complications: a prospective study in Nepal, Paper presented at 129th Annual Meeting of American Public Health Association. Atlanta, 21—25 October 2001.

- C Lenton, J Fortney, C Vickery. Safe motherhood at the district hospital: Report of an identification mission. 1995; Options: London.

- Department for International Development. Activity to output monitoring and comments on inception phase progress. 1997; Nepal Safer Motherhood Project; Ministry of Health: Kathmandu.

- Ministry of Health, Family Health Division and UNICEF. National Maternity Care Guidelines, Nepal. 1996; MOH and UNICEF: Kathmandu.

- Safe motherhood policy of His Majesty’s Government of Nepal Journal of Nepal Medical Association 34: 1996; 162–164.

- Ministry of Health. Safe Motherhood Policy. 1998; Family Health Division, Ministry of Health: Kathmandu.

- RK Adhikari. Towards liberalizing abortion law in Nepal Journal of Nepal Medical Association. 34: 1996; 177–179.

- M Hoftun, W Raeper, J Whelpton. People, Politics and Ideology: Democracy and Social Change in Nepal. 1999; Mandala Book Point: Kathmandu.

- K Ogura. Kathmandu Spring: The People’s Movement of 1990. 1990; Himal Books: Kathmandu.

- LK Manandhar, K Bhattachan. Gender and Democracy in Nepal. 2001; Women’s Studies Program and Friedrich Ebert Stiftung: Kathmandu.

- Integrated Development Systems. Hospital based study of abortion in Nepal. Project Report. 1985; IDS: Kathmandu.

- PJ Thapa, S Thapa, N Shrestha. A hospital-based study of abortion in Nepal Studies in Family Planning. 23(5): 1992; 311–318.

- Integrated Development Systems. A study of rural-based abortion in Nepal. Project Report. 1986; IDS: Kathmandu.

- S Thapa, PJ Thapa, N Shrestha. Abortion in Nepal: emerging insights. LJ Severy. Advances in Population: Psychosocial Perspectives. Vol.2: 1994; Jessica Kingsley Publishers: London, 253–270.

- AK Tamang, N Shrestha, K Sharma. Determinants of induced abortions and subsequent reproductive behavior among women in three urban districts of Nepal. AI Mundigo, C Indriso. Abortion in the Developing World. 1999; Vistaar Publications: New Delhi, 167–190.

- Ministry of Health. Family Health Survey 1996. Kathmandu: Ministry of Health, New ERA; Calverton: Macro International Inc, 1997.

- LR Pathak, DS Malla, A Pradhan. Maternal Mortality and Morbidity Study. 1998; Ministry of Health: Kathmandu.

- Ministry of Law, Justice, and Parliamentary Affairs. The Constitution of the Kingdom of Nepal, 2047 (1991). 1991; Ministry of Law, Justice and Parliamentary Affairs: Kathmandu.

- Institute for Integrated Development Studies. Mass Media and Democratization. 1996; IIDS: Kathmandu.

- P Kharel. Media Nepal 2000. 2001; Nepal Press Institute: Kathmandu.

- A Bill Framed to Provide Protection of Pregnancy. 1997; Family Planning Association of Nepal: Kathmandu.

- World Health Organization. Complications of Abortion: Technical and Managerial Guidelines for Prevention and Treatment. 1995; WHO: Geneva.

- Ministry of Law, Justice and Parliamentary Affairs. New Recommendations on Muluki Ain 11th Amendment Bill, approved by the House of Representatives. 1997; Ministry of Law, Justice, and Parliamentary Affairs: Kathmandu.

- S Pradhan-Malla. Report of a conference-workshop on existing legal codes and provisions relating to women’s rights and necessary amendments on them. Conference jointly organized by the National Assembly Social Justice Committee, Mainstreaming Gender Equity Program, and United Nations Development Programme, Godavari, 25—26 March 2000. (In Nepali). 2000; Forum for Women, Law and Development: Kathmandu (Draft report)

- Richoi Associates. Safe Pregnancy Termination Service Order, 2059. 2002; Ministry of Health, Health Services Department, Family Health Division: Kathmandu.

- Ministry of Health. National Safe Abortion Policy and Strategy. 2002; Ministry of Health, Department of Health Services, Family Health Division: Kathmandu (Draft)

- Ministry of Health. Safe Abortion Service Procedure. Draft. 2003; Ministry of Health, Department of Health Services, Family Health Division: Kathmandu.

- Abortion Task Force. Workshop Report — National Implementation Plan for Abortion Services. 18-19 November 2002. Ministry of Health, Department of Health Services, Family Health Division: Kathmandu.

- Ministry of Health. National Medical Standard for Reproductive Health: Vol. I, Contraceptive Services. 2001; Ministry of Health, Department of Health Services, Family Health Division: Kathmandu.

- Thapa S. Unmet need for family planning in Nepal. Paper presented at a meeting organized by Department of Health Services, Ministry of Health, and Office of Health and Family Planning, US Agency for International Development. Kathmandu: 20 March 2002.