Abstract

In Nepal, the effects of the low social status of women and lack of access to health care and family planning have resulted in a maternal mortality ratio that is among the highest in South Asia. By the mid-1990s, the contribution of unsafe abortions to maternal deaths and morbidity was acknowledged by key individuals in the Ministry of Health and Department of Health Services. Advocacy for abortion law reform over several decades culminated in the passage of a new law on abortion in 2002. The parliamentary process took almost four years from the tabling of the bill. Almost two years elapsed between the passage of the bill and approval of the Procedural Order for implementing it. This paper describes the development of policy and programme strategies for implementing the new law, led by the government in collaboration with NGOs, donors and other stakeholders. During that time, documents required for implementation were prepared, training of service providers was begun and a model service delivery and training site was established in Kathmandu Maternity Hospital. Simple systems to enable rapid expansion of services and a women-friendly approach were devised, promoting universal availability of affordable services provided by physicians and eventually nurses, the latter particularly in remote and rural areas, where 88% of the population live.

Résumé

Au Népal, le statut social peu élevé des femmes et leur manque d’accès aux soins de santé etàla planification familiale expliquent le taux de mortalité maternelle parmi les plus hauts d’Asie du Sud. A la moitié des années 90, des fonctionnaires clés du Ministère de la santé et du Département des services de santé ont reconnu l’impact des avortements non médicalisés sur la mortalité et la morbidité maternelles. Le plaidoyer pour une réforme de la loi sur l’avortement a culminé dans l’adoption d’une nouvelle législation en 2002. Le processus parlementaire a pris quatre ans depuis le dépÁt du projet de loi. Deux autres années se sont écoulées avant la publication du décret d’application. L’article décrit la préparation de politiques et de stratégies pour mettre en æuvre la nouvelle loi, sous la direction du gouvernement avec des ONG, des donateurs et d’autres acteurs. Pendant cette période, les autorités ont rédigé les documents d’application, commencéàformer les prestataires de services et créé un site pilote de formation et de servicesàla Maternité de Katmandou. Des systèmes simples qui permettent une expansion rapide des services et une approche conviviale ont été conus, favorisant une disponibilité généralisée de services abordables assurés par des médecins ou, dans les zones rurales isolées où réside 88% de la population, par des infirmières.

Resumen

En Nepal, el bajo nivel social de las mujeres y la falta de acceso a los servicios de salud y de planificación familiar ocasionan uno de los más altos ándices de mortalidad materna en Asia meridional. Para mediados de los noventa, funcionarios clave del Ministerio de Salud y el Departamento de Servicios de Salud reconocieron el aporte del aborto inseguro a la morbimortalidad materna. La defensa de reformas en la ley de aborto culminó en la aprobación de una nueva ley en 2002. El proceso parlamentario duró casi cuatro años desde la presentación del proyecto de ley. Casi dos años mas transcurrieron antes de la aprobación de la Orden Procesal para aplicarla. Este artáculo describe la formulación de estrategias de poláticas y programas para dar cumplimiento a la nueva ley, dirigidos por el gobierno en colaboración con las ONG, los donantes y otras partes interesadas. Durante ese tiempo, se prepararon los documentos necesarios para su cumplimiento, se inició la capacitación de los profesionales de la salud y se estableció un lugar modelo para la prestación de servicios y la capacitación en el Hospital de Maternidad de Katmandú. Se idearon sistemas sencillos para permitir la rápida ampliación de los servicios y un enfoque centrado en la mujer, lo cual promovió la disponibilidad universal de los servicios a precios asequibles prestados por médicos y, con el tiempo, por enfermeras, estas últimas particularmente en las zonas remotas y rurales donde reside el 88% de la población.

Unsafe abortions have contributed significantly to the high maternal mortality ratio in Nepal, which the government has been committed to reducing since 1991 under the National Health Policy and more recently as part of the Millennium Development Goals. Legislative change that would meet the needs of all women and promote rapid and effective implementation of “women-friendly” services based on choice, access and quality of care, was perceived as a necessary part of this process.

The 11th amendment of the Legal Code of Nepal (Muluki Ain) legalised abortion for a broad range of conditions in March 2002 and received Royal Assent in September that year. In December 2003 the Procedural Order for implementation of the new legislation was passed, enabling the provision of services to begin. In the interim, the focus of activities moved from advocacy for legal change to the development of strategies and plans for implementing services.

Under the previous legislation, abortion was only allowed to save the life of the woman, certified by the signature of two physicians. Nepal was among the few countries in the world where the law was being enforced, and women sent to prison for having an abortion. The sentence could be three years or more, depending on the circumstances,Citation1 with a possible pardon after completion of half the sentence. If the crime was deemed to be infanticide, the sentence could be up to 20 years.Citation2 In practice, the law did not clearly distinguish between abortion and infanticide, and many poor and illiterate women received long prison sentences in court proceedings of which they had no understanding. Across the country, women — especially the poorest — were languishing in jail, often having been reported by their own relatives, sometimes even after a spontaneous abortion. In 1997 a nationwide survey estimated that 20% of the women in Nepali jails had been convicted on charges of abortion or infanticide.Citation1 In April 2004, after legalisation of abortion, 31 women were still held in prisons across the country on charges of infanticide. By November 2004, 18 of them had been released (Personal communication, Binda Magar, Forum for Women, Law and Development, November 2004). Mostly poor and illiterate, they were kept in miserable conditions, unable to afford legal assistance or even to understand what had happened to them. Significantly, only women were imprisoned, their male partners and the abortion providers were not held accountable. By contrast, middle- and upper-class women were able to access services from private practitioners, paying for both medical and legal safety. Many better-off women also travelled across the border to India for services (Personal communication, Jyotsna Tamang, Centre for Research on Environment, Health and Population Activities, October 2004).

In contrast, the new law represents a huge step forward. Abortion is allowed up to 12 weeks for any woman with her consent; up to 18 weeks if the pregnancy is the result of rape or incest, and at any time during the pregnancy on the advice of a medical practitioner if the life, or physical or mental health of the woman are at risk, or the fetus is deformed or has a condition incompatible with life. The consent of the husband or guardian is not required for women over 16 years of age, and for those under 16, the “guardian” can include any adult friend or family member.

This paper describes the development of policy and programme strategies for implementing the new abortion law in the context of a poor, mostly rural, country with limited health care resources, which took place during the almost two years between the passage of the bill and approval of the Procedural Order for implementing it.

Women’s health and status in Nepal

Public health services in Nepal are constrained by resource and staff shortages, particularly in rural areas, where 88% of the population live, and 44% of households subsist below the poverty line.Citation3 In many remote areas government health services are virtually non-existent, with health posts infrequently staffed and medicines unavailable or out of date. In such circumstances, people continue to use traditional healers and remedies, and many do not have access to or knowledge about modern family planning. Thus, despite 40 years of family planning initiatives, only an estimated 59% of the demand is being met, and contraceptive use among married women of reproductive age is only 39%.Citation4

The position of women in traditional communities is physically and socially harsh, with girl children systematically discriminated against, receiving less food,Citation5 doing more work from an earlier age and less likely to attend school than their brothers. The average literacy rate for women (35%) is only half that of men.Citation4 A daughter will be married at the earliest opportunity, frequently in her early teens. Living with her husband’s family, she will occupy the lowest position, her treatment directly related to her ability to produce sons and work hard.Citation6 Any decisions related to her life and health will be taken by her husband and his family. Thus, although women carry all the social responsibility for producing and bringing up a healthy family with more sons, they have no decision-making power. They are blamed for unwanted pregnancy — whether from rape or incest or just too many children. Without the permission of their husband and family, however, they are unable to use family planning. Women in rural areas suffer most, as traditions are more closely adhered to, and in desperation they are often forced into the hands of unscrupulous local “quacks”, who use a variety of unsafe methods to induce abortion. When complications arise, women are usually afraid to seek medical help until it is too late. In urban areas, private practitioners have offered abortion services for many years, using the loophole provided by the wording of the law, which allowed abortion on health grounds with the signature of two physicians. However, the cost is beyond the reach of most poor women, and the cheaper options carry greater risks, so that the poorest women are the most vulnerable.

The combined effect of the low social status of women and lack of access to health care and family planning resulted in a maternal mortality ratio that is among the highest in South Asia, at 539 to 100,000 live births.Citation7 Complications from unsafe abortions have contributed significantly to this. It has been estimated that 53.7% of gynaecological and obstetric hospital admissions were due to induced abortion complications,Citation8 and 20% of the maternal deaths in health facilities.Citation9 This does not account for the many women dying at home, either because they were too far from a hospital or afraid to risk going to a public institution because of the illegal status of abortion. One community study in 1994 estimated the total abortion rate to be 117 per 1,000 women of reproductive age per year.Citation10

The financial implications were also serious. The estimated cost of managing abortion complications ranges from US$20—133,Citation10 depending on severity, technique used and socio-economic factors. Post-abortion care services were introduced in 1995 and are now available in 45 of the 72 major public hospitals across the country (records from the Department of Health Services), with a number of development programmes, mainly funded through USAID, providing support for upgrading of facilities and training of physicians and nurses.Footnote*

Although the availability of post-abortion care represented a major step forward, saving the lives of many women and helping them to access family planning services, it did not address the fundamental problem of complications and deaths stemming from the illegal status of abortion.

Small beginnings: a perceived need for change

From small beginnings in the 1980s, and increasingly throughout the 1990s, a number of influences were simultaneously working towards change, based on a public health perspective (with a focus on maternal mortality), legal and human rights issues (women in prison), and international influences (including the experiences of neighbouring countries). In different ways, each of these began to affect public awareness and opinion, gradually wearing away entrenched, traditional views about abortion. A critical factor was the presence of strong advocates in key positions, who were able to move things forward and to forge links between the different stakeholders.

Around 1980 an obstetrician—gynaecologist working at the Maternity Hospital in Kathmandu noted the number of women suffering and dying from the medical and social consequences of abortion-related complications. His observations convinced him that abortion should be legalised, and he submitted articles to a number of daily newspapers outlining his views. This generated national discussion, eventually resulting in an interview aired on BBC Sri Lanka and BBC UK, giving the issue international attention.Citation11 In 1990, the same physician took part in a public debate on legalisation of abortion on Nepal Television and challenged anti-abortion views, stating that he intended to perform abortions. In 1992 he began working with the Family Planning Association of Nepal, performing mini-laparotomy sterilisations and menstrual regulation.

While touring the country’s jails in 1993—95, the Secretary of the Home Ministry noted the number of women imprisoned on abortion charges and their poor conditions and lack of rights, and determined to address the issue. Working with the Chairman of the Family Planning Association of Nepal, also a member of the Upper House of Parliament, he drafted abortion legislation for submission to the Upper House as a private bill in 1996. Despite the support of a number of parliamentarians it was rejected, and failed again in 1997, when presented as part of the Women’s Property Rights Bill. At this stage the issue did not have a high national profile, as the energies of women’s reform groups concentrated on women’s property rights rather than abortion.

By the end of the 1990s, the contribution of unsafe abortions to the high levels of maternal mortality and morbidity, highlighted by the National Maternal Mortality and Morbidity Study,Citation8 was widely acknowledged, with key individuals within the Ministry of Health and the Department of Health Services recognising the need for change.

NGO-led advocacy efforts

During the mid-1990s, the Center for Research on Environment, Health and Population Activities (CREHPA), a non-governmental organisation (NGO) specialising in research and advocacy, became involved in the abortion issue, carrying out a number of studies on the effects of the illegal status of abortion on women’s rights and welfare, particularly poor women. These studies complemented a World Health Organization (WHO) funded longitudinal study carried out in 1992—94Citation12 on the types of abortions women were undergoing in Nepal, and the resulting deaths and costs of the post-abortion treatment provided at three large Kathmandu hospitals. In 1996, CREHPA conducted an opinion poll on abortionCitation13 to ascertain public views on abortion and its legalisation, which indicated that most sectors of Nepali society were broadly in favour of legalisation.

In 1995, the Forum for Women, Law and Development (FWLD), a national NGO advocating legal reform and human rights, began working with women imprisoned on abortion-related charges. They published a number of newspaper articIes on their work, claiming that the illegal status of abortion constituted a violation of human rights, and in 2003 produced an updated study on women in prison.Citation14

From the mid-1990s, advocacy work by individuals and organisations stimulated the interest of activist women’s groups, and the issue gained national profile and momentum. CREHPA made extensive use of the press, stressing the public health consequences of maternal deaths and the burden on public hospitals caused by admissions for abortion complications. Meanwhile, FWLD concentrated on lobbying key decision-makers and members of parliament, building coalitions with women’s groups and other NGOs, focusing on legal issues related to women in prison and the lack of differentiation between induced and spontaneous abortion.

In 1999, CREHPA began working with others to design an advocacy strategy, developing posters about the prevention of unsafe abortion. In 1999 and 2000 they submitted two policy memoranda to Parliament, explaining the case for legalisation of abortion, and in 2001 they worked with the Family Health Division of the Department of Health Services on an advocacy paper. FWLD also worked closely with the Centre for Reproductive Law and Policy in New York to draft legislation amending all gender discriminatory laws in the Legal Code, including the prohibition of abortion. They continued to document the plight of women in prison on abortion-related crimes, publishing a paper in 2002.Citation2 The movement for change was growing, as advocacy to reduce unsafe abortion was also a major item on the agenda of the 1999 Cairo+5 conference, and many other positive changes internationally.

Around 2000, various influencing factors gathered momentum; of particular importance was the growing support of the Ministry of Health and Department of Health Services, which played leading roles in the later stages of the process of changing the law.

During the mid- 1990s, the Director of the Family Health Division, through his position as Vice-Chairman of the Family Planning Association of Nepal, arranged discussions with different influential groups, including women parliamentarians, the Nepal Medical Association, lawyers and youth groups. In November 2000, as Family Health Division Director, he raised the issue at a national level Reproductive Health Steering Committee meeting, at which the Secretaries of seven key Ministries were present. With the support of donor agency representatives, he succeeded in persuading these influential Secretaries to support the submission of a proposal to amend the abortion law to parliament, based on the high priority accorded by the health sector to reducing the national maternal mortality ratio. The proposal was accepted, and the Ministry of Health requested Family Health Division to draft an abortion section for inclusion in the 11th amendment to the Legal Code, scheduled for parliamentary debate. This amendment also included reforms in other areas of women’s rights, particularly property rights.Citation15

Meanwhile, with the help of CREHPA and FWLD, leaflets were developed on the prevention of unsafe abortion and distributed to all parliamentarians and Ministry Secretaries. The Secretary of the Ministry for Women and Social Welfare presented the 11th amendment to Parliament, and the debate focused mainly on the ethical, religious and social aspects of accessible legal abortion. After several months of discussion, the principle of safe abortion was agreed upon, and in March 2002 the amendment was passed.

Government-led preparations for implementing the new law

In February 2002, when passage of the amendment appeared imminent, the Family Health Division formed an Abortion Task Force to draft the Procedural Order for implementation of the amendment and the Policy and Strategy documents. Royal Assent was given in September 2002, and the Procedural Order submitted to the Cabinet. However, changes in the government delayed approval until December 2003, almost two years after the new law was passed, creating a frustrating grey period during which abortion was technically no longer illegal, but public services could not be provided.

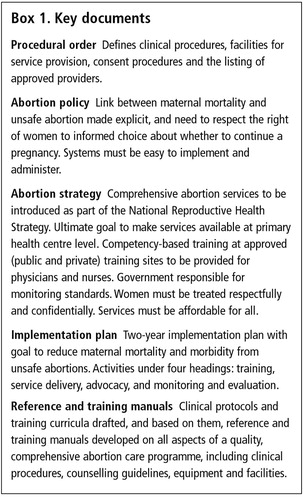

The Abortion Task Force was chaired by Family Health Division, with membership drawn from the Nepal Society for Obstetricians and Gynecologists, the Nepal Safer Motherhood Project (funded by DFID UK), German Technical Assistance (GTZ) Health Sector Support Programme and CREHPA. GTZ, DFID and Ipas provided technical and financial support. Much of its work was centred on developing key documents (Box 1).

The international literature was reviewed to learn from the experiences of other countries where abortion had been legalised. These countries included India, where many barriers had arisen as a result of complex regulations and lack of health service infrastructure in rural areas, South Africa and Guyana, both of which had sought through their laws, with varying success, to minimise barriers.Citation16 Many of the recommendations contained in the WHO guidance,Citation17 available in draft at the time, were also incorporated. Based on global lessons learned, the amended law, policies and procedures developed were very liberal, in order to make implementation as widespread and straightforward as possible and to minimise barriers to women needing services.

Principles and priorities for implementing the new law

In June 2002, a policy support paper submitted to the Family Health Division,Citation18 based on the literature review, highlighted three cross-cutting principles which apply to successful implementation of abortion law reform:

| • | Advocacy does not end with the passage of a liberal law. In other countries, continued advocacy has been needed to ensure anti-abortion forces do not overturn or curtail hard-won legal reforms, that health care providers are on board and willing to provide safe services and that women are aware of their rights and able to access services. | ||||

| • | A progressive law that cannot be fully implemented is not enough of an improvement, although it may prevent women being harassed and imprisoned. In addition, policies and procedural guidelines must be sufficiently flexible to allow rapid implementation of services with limited resources, without compromising safety or standards. | ||||

| • | Strengthened family planning services must become an integral part of comprehensive abortion care, in order to reduce unwanted pregnancy and achieve a significant reduction in maternal mortality. | ||||

Based on these three principles, 35 detailed recommendations were made, grouped under ten major headings, which included: the need for changes in social attitudes towards abortion, meeting women’s needs, policy and standards, health system barriers, funding, health policy framework, cross-sector linkages and partnerships, and monitoring and evaluation.

The priorities for meeting women’s needs were summarised as the five Cs:

| • | Convenience and accessibility of services. | ||||

| • | Confidentiality — relating to both the physical layout of facilities and service providers’ attitudes. | ||||

| • | Caring and comfort — including service providers’ attitudes and pain control techniques. | ||||

| • | Cost — ensuring that no woman is denied services because of inability to pay. | ||||

| • | Contraception — effective counselling and availability of appropriate methods. | ||||

In the resource-poor context of Nepal, serving the needs of all women, including the poor and illiterate, poses a major challenge. Two key decisions were, first, to train nurse providers, as that would facilitate the availability of services at small district hospitals and primary health care centres, and second to focus on certification of service providers after satisfactory completion of competency-based training, keeping criteria for approved facilities to the minimum compatible with safe services. Manual vacuum aspiration (MVA) was chosen as the recommended abortion method, using the experience gained from post-abortion care services, for which MVA is the accepted technique, and so that nurses could also be trained as service providers.

A two-day workshopCitation19 was held in November 2002, to begin the process of developing an implementation plan. Representatives attended from all the major stakeholders, including the government, donors, national and international NGOs. The objectives were to reach a common understanding of what comprehensive abortion services involved, reach consensus on the goals and purpose of the national safe abortion plan, and formulate a two-year plan for the introduction of services.

As it had completed its tasks,Citation19 the Abortion Task Force was dissolved. A new body, the Technical Committee for the Implementation of Comprehensive Abortion Services (TCIC), was formed to assist the government with planning and implementation of the law and new terms of reference were drafted. The four working groups remained, continuing the work they had begun under the Task Force.

The TCIC has a clinical coordinator, an administrator, and input from a consultant technical advisor, with funding and technical support provided by DFID, Ipas and PATH. The full committee, around 30 representatives from national and international NGOs and government departments, meets approximately four times a year. A core group, consisting of representatives from Family Health Division, DFID, GTZ and the secretariat, meet more often, as required. The working groups meet separately, reporting back to the core group and the main committee.

Abortion services are coordinated by the Department of Health Services Reproductive Health Coordination Committee, with central responsibility for listing of service providers resting with the Department. At local level, District Health Offices are responsible for implementation and supervision of services, including listing of service providers and facilities. The process associated with listing has successfully been kept simple.

Training and service delivery

To facilitate rapid implementation of services across the country, a cascade approach was used and both the public and private sector involved. Activities began with a three-day orientation for senior gynaecologists, including an update on clinical procedures, infection prevention and counselling. In view of their experience, this was considered sufficient for their being listed as competent practitioners. The second stage has been training of trainers. As of June 2004, 20 participants from zonal public hospitals across the country, medical colleges (to promote inclusion of abortion in pre-service training), and private institutions had received training. Ultimately these facilities will be developed as training sites. The nine-day course includes clinical skills, counselling, infection prevention, orientation on the law and training skills. The third stage, training of service providers, has begun in Kathmandu and will later be extended to training sites at zonal hospitals outside the capital. As of December 2004, 99 physician service providers had been trained and 53 nurse counsellors/assistants. There are plans to begin training nurses as service providers within the next year.

The first service and training site was developed as a model centre at the Maternity Hospital in Kathmandu, with excellent facilities to cater for a high caseload. At smaller hospitals and health centres it is anticipated that, where possible, training and services will be integrated into existing facilities, or modest renovations will be undertaken to provide space. Basic equipment such as MVA and sterilisation equipment and specula will be distributed to service providers on completion of their training. The guidelines also allow for private hospitals and NGOs to serve as training centres, once trainers and facilities receive government approval.

Information dissemination

Plans for disseminating information are still at the planning stage, since it would be irresponsible to create demand before services can meet it. Energies have initially focused on disseminating information about the legal changes to law enforcement authorities, to make them aware that women should no longer be arrested or imprisoned on abortion charges. However, despite these efforts arrests of women have continued.Citation14 Advocacy NGOs have been carrying out district-level awareness-raising and orientation on the new law, and using the media to disseminate information at national level. At the same time, the government and NGOs have begun developing messages about the new law, availability of services and avoidance of unsafe abortions, for dissemination through the media. Representatives from Family Health Division have begun visiting districts where the first service providers have been trained, to orientate hospital staff, the District Health Office and local officials about the details of the law. With technical assistance from PATH, work has also begun on drafting a broader Behaviour Change Communication Strategy, to address current attitudes and practices related to abortion, based on formative research carried out by CREHPA.

Monitoring and evaluation of services will be the responsibility of District Health Offices and Family Health Division, and tools for this purpose, including registration and listing forms, have been drafted. Evaluation of training is the responsibility of the TCIC, including follow-up to assess the competency of trained providers and provide advice on the establishment of services.

Challenges for the future

Much has been achieved of which the country can be proud, although many challenges remain on the road to universal availability of safe, accessible abortion services for women in Nepal. Not least among the challenges is the prevailing social stigma, which associates abortion with “loose, immoral behaviour”. The status of women remains low, particularly in rural areas, making it difficult for them to access information and make decisions about obtaining services at a sufficiently early stage to remain within the law (which only permits abortion up to 12 weeks under normal circumstances). Although the government is proceeding with training of service providers and listing of service sites as rapidly as possible, there are still many areas where services and information are not yet available. Even where they are available, many women are not familiar with the concept of gestation dates, and thus are presenting at clinics when they are already beyond the legally specified limit of 12 weeks (Personal communication, Sabitri Kishore, Maternity Hospital, Kathmandu, October 2004).

Of immediate importance is the need to ensure that information about the changes in the law is fully disseminated, and to get local authorities to stop imprisoning women on abortion charges, particularly in remote rural areas. The 13 women remaining in prison must also be released at the earliest possible date.

A key issue will be ensuring that safe abortion services are combined with increased access to effective family planning services, and strengthening links with the health care system, so that women are able to avoid repeat abortions.

The geographical and resource constraints of Nepal pose a major challenge to country-wide implementation of programme plans, with poor roads and communications, and staff shortages making it difficult to maintain high standards. The situation is further exacerbated by the current armed conflict and harassment of local people, which is widely affecting travel in rural areas, causing fear, including among health workers, and making planning difficult. For this reason, a key issue will be the training of nurses to provide safe services where doctors are often not available, and to reach poor women in remote areas, who are most at risk from unsafe abortions.

As safe abortion becomes more available, the need for post-abortion care for dealing with complications will be reduced. However, certain donor countries only allow the use of government funding for post-abortion care, not for safe abortions. Since post-abortion care will still be needed for women suffering from incomplete spontaneous abortions, the government is not in a position to compromise this funding, and so the natural combination of the two services is unlikely to happen in the near future.

Conclusions

The changes in the law were largely based on the need to address the high maternal mortality ratio from unsafe abortions, treating the needs and rights of women as paramount. Despite the traditionally conservative social attitudes of the country, those in authority became convinced that legalisation of abortion and the provision of safe, accessible services would prevent complications and deaths. Interestingly, despite the strongly religious nature of Nepali society, there have been no major public objections to the reforms. The delay of almost two years between the passing of the reform bill and the Procedural Order approving the new law created a grey period during which abortion was no longer illegal, but public services could not be provided. Perseverance was needed to keep up the momentum for change and to plan for immediate action when approval was achieved.

Services began at the Maternity Hospital in Kathmandu in March 2004, with demand building quickly. As of December 2004, around 2,000 women had had legal abortions there. A further 22 sites (public and private) have also begun providing services, although the caseload has been slower to build up. Forty-three sites (26 public and 17 private) across the country have completed the listing process and are ready to begin services. There are now trained physician service providers in 30 of the 75 districts of the country. Plans for a second training site outside Kathmandu are underway.

The central lessons learnt are that from the early stages of the process, key members of the government have played a leading role in facilitating change and guiding policy development, and that effective collaboration and partnerships with a wide and diverse group of stakeholders to support the government in achieving the required changes have been essential.

Acknowledgements

Special recognition goes to Dr Yashovardhan Pradhan (Department of Health Services, Nepal), Ms Anne Erpelding (GTZ Cambodia), Ms Susan Clapham (DFID Nepal), Ms Mary Luke (Ipas USA) and Ms Bela Ganatra (Ipas India) for their technical advice and support. We would also like to acknowledge Dr Laxmi Raj Pathak (MoH Nepal), Mr Anand Tamang (CREHPA Nepal), Dr Bhola Rijal (Ob—Gyn), and Ms Binda Magar (FWLD Nepal) who played significant roles in the abortion law reform process and gave invaluable input to this paper.

Notes

* No research updating this figure could be found. However, the charge for post-abortion care services at public hospitals is currently Rs.500 (US$7) plus the cost of any additional drugs needed. In cases of severe infection, the total cost can be as high as Rs.1,500 (US$21), which is borne by the woman unless she is very poor, in which case the hospital might subsidise her. The establishment of post-abortion care services has made care of women with complications less expensive, so we consider the estimate from 1994 still valid for the purposes of this paper.

References

- AK Tamang, M Puri, B Nepal. Women in Prison in Nepal for Abortion. 2000; Centre for Reproductive Law and Policy and CREHPA: Kathmandu.

- Centre for Research on Environment, Health and Population Activities and Forum for Women Law and Development. Abortion in Nepal: Women Imprisoned. 2002; CREPHA and FWLD: Kathmandu.

- Central Bureau of Statistics, Nepal Living Standard Survey. 1996; CBS: Kathmandu.

- Family Health Division, Ministry of Health Nepal, New Era and ORC Macro. Demographic and Health Survey 2001. 2001; ORC Macro: Calverton MD.

- J Gittelsohn. Opening the box: intra-household food allocation in rural Nepal Social Science and Medicine. 33(10): 1991; 1141–1154.

- J Gittelsohn, M Thapa, LT Landman. Cultural factors, caloric intake and micronutrient sufficiency in rural Nepali households Social Science and Medicine. 44(11): 1997; 1739–1749.

- UNICEF. The State of the World’s Children 2004. Table 6: Demographic Indicators. At: http://www.unicef.org/sowc04/sowc04_tables.html. Accessed 24 December 2003

- Ministry of Health Nepal. National Maternal Mortality and Morbidity Study. 1998; MoH: Kathmandu.

- His Majesty’s Government Nepal and UNICEF. Needs Assessment on the Availability of Emergency Obstetric Care Services. 2000; HMG Nepal/UNICEF: Kathmandu.

- S Thapa, PJ Thapa, N Shrestha. Abortion in Nepal: emerging insights Journal of Nepal Medical Association. 32: 1994; 175–190.

- Forum for Women Law and Development and Planned Parenthood Global Partners. Struggles to Legalise Abortion in Nepal and Challenges Ahead. No. 70. 2003; FWLD: Kathmandu.

- AK Tamang, N Shrestha, K Sharma. Determinants of abortion and subsequent reproductive behaviour among women of three urban districts of Nepal. Al Mundigo, C Infriso. Abortion in the Developing World. 1999; Vistaar Publications: New Delhi, 167–190.

- Centre for Research on Environment, Health and Population Activities. Opinion Poll Survey on Abortion Rights for Women. August 1996

- Forum for Women, Law and Development, Center for Reproductive Rights, Ipas. According to the findings of the district prison visit by FWLD, CRLP and Ipas, June 2003. (Unpublished report).

- Forum for Women, Law and Development. Country Code Eleventh Amendment Bill and Woman’s Rights. No.45. 2001; FWLD: Kathmandu.

- Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, Government of India. Report on a National Conference on Making Early Abortion Safe and Accessible. Agra, India. 11—13 October 2000.

- World Health Organization. Safe Abortion: Technical and Policy Guidance for Health Systems. 2003; WHO: Geneva.

- McCall M. Policy Support Paper: A Review of Global Lessons Learned and Recommendations to His Majesty’s Government of Nepal on the Implementation of Abortion Services. Kathmandu, 2002. (Unpublished report)

- Ministry of Health, Department of Health Services, Family Health Division. National Implementation Plan for Comprehensive Abortion Services: Workshop Report. Kathmandu, 2002.