Abstract

In Brazil, abortion is legally restricted but highly prevalent. The objective of this study was to obtain data on the opinions of obstetrician—gynaecologists regarding abortion and to verify whether there is consistency between their personal opinion with respect to abortion and their private decision when confronted personally with an unwanted pregnancy or with a request for abortion from a patient or relative. A structured questionnaire was sent to obstetrician—gynaecologists, members of the Brazilian Federation of Gynaecological and Obstetrical Societies (FEBRASGO). A total of 4,261 physicians responded, a 30% response rate. Almost a quarter of female physicians and a third of male physicians had had an unwanted pregnancy, and 80% of these were aborted. Even among those for whom religion was very important, almost 70% chose abortion when personally faced with an unwanted pregnancy. Twice as many respondents accepted abortion as a solution for themselves or their partners as for their patients. The difference was much smaller only if the physician had personally experienced abortion. Thus, the closer physicians are to the problem of abortion, the greater their understanding that there are circumstances under which abortion is the best or only alternative. We expect the publication of these data to contribute towards liberalisation of the abortion law in Brazil.

Résumé

Au Brésil, l’avortement est limité par la loi, mais très fréquent. Cette étude souhaitait recueillir l’avis des gynécologues-obstétriciens sur l’avortement et déterminer si leurs opinions personnelles étaient cohérentes avec leurs décisions privées quand ils ont été confrontés personnellementàune grossesse non désirée ouàla demande d’avortement d’une patiente ou parente. Un questionnaire structuré a été adressé aux adhérents de la Fédération brésilienne des sociétés de gynécologie et d’obstétrique (FEBRASGO). Au total, 4261 médecins ont répondu, soit 30%. Près d’un quart des femmes médecins et un tiers des hommes médecins avaient été confrontésàdes grossesses non désirées, et 80% s’étaient terminées par un avortement. MÁme parmi ceux pour qui la religion était très importante, près de 70% avaient choisi l’avortement. Deux fois plus de répondants acceptaient l’avortement comme solution pour eux-mÁmes ou leurs partenaires que pour leurs patientes. La différence était beaucoup plus faible seulement si le médecin avait connu personnellement un avortement. Ainsi, plus les médecins étaient proches du problème de l’avortement, mieux ils comprenaient qu’il existe des circonstances dans lesquelles l’avortement est la meilleure ou la seule solution. Nous pensons que la publication de ces données contribueraàla libéralisation de la législation sur l’avortement au Brésil.

Resumen

En Brasil, el aborto es legalmente restringido pero muy frecuente. Este estudio procura obtener datos sobre las opiniones de los gineco-obstetras respecto al aborto y determinar si éstas son consecuentes con sus decisiones privadas cuando enfrentan personalmente un embarazo no deseado o una solicitud de aborto de una paciente o pariente. Se envió un cuestionario estructurado a los gineco-obstetras afiliados a la Federación Brasileña de Sociedades de Ginecologáa y Obstetricia (FEBRASGO). Un total de 4,261 médicos respondieron, con un ándice de respuesta del 30%. Casi una cuarta parte de las médicas y una tercera parte de los médicos habáan enfrentado un caso de embarazo no deseado, y el 80% de éstos fueron abortados. Aun entre aquéllas para quienes la religión es muy importante, casi el 70% optó por interrumpir un embarazo no deseado. El doble de los respondedores aceptó el aborto como una solución tanto para ellos mismos o sus parejas como para sus pacientes. La diferencia fue mucho menor sólo si el médico habáa experimentado un aborto personalmente. Por tanto, mientras más se acercaban los médicos al problema del aborto, mayor era su entendimiento de que existen circunstancias en las que el aborto es la mejor o única opción. Esperamos que la publicación de estos datos contribuya hacia la liberalización de la ley de aborto en Brasil.

In most Latin American countries, abortion is legally restricted but highly prevalent, with an abortion rate per 100 women of reproductive age 3—10 times higher than that of Western European countries, where abortion is legally permitted and accessible.Citation1, Citation2 Because abortion is also condemned by the Catholic Church, access to safe abortion in the circumstances permitted by law is denied to the great majority of women.

Unsafe abortion is a serious public health problem and one of the major causes of preventable maternal deaths.Citation3, Citation4 The ICPD and UN women’s conferences in the 1990s recommended that where abortion is legal, it should be made safe and accessible to women.Citation5, Citation6 These recommendations have rarely been put into practice in Latin America. One reason is that physicians are afraid of the legal and social repercussions of practising abortion, even within the law. On the other hand, they are members of societies in which abortion is broadly practised, and on more than one occasion, physicians may find themselves faced with a situation in which abortion is needed. They may even have to terminate their own unwanted pregnancy or that of a partner, close relative or friend.

Brazilian law permits a physician to perform abortion only if the pregnancy is a result of rape or if there is no other way of saving the woman’s life.Citation7 In all other circumstances, abortion is illegal, and prison sentences can range from 1—10 years for the woman and the provider.Citation8 However, prosecution of a woman is a very rare event and we are unaware of any woman in Brazil who has been sentenced to prison for having had an abortion. In spite of the law, it is estimated that 940,660 illegal abortions were carried out in Brazil in 1998.Citation9 In addition, although sexual violence is highly prevalent, legal abortion in cases of rape is rarely performed in public hospitals. This means that a large number of women who should have access to safe abortion in a hospital environment are risking their lives by being forced to resort to clandestine abortions.

The need to provide abortions for women who are legally entitled to seek them has been raised by women’s organisations and a few obstetrician—gynaecologists since the early 1980s. In 1987 and 1988, the cities of Rio de Janeiro and São Paulo established specific services for women requesting legal abortion. Considering the population of 170 million Brazilians, only two hospitals in São Paulo, one in Rio de Janeiro and one in Campinas had carried out abortions up to 1995 for women victims of rape. No more than 20—30 women rape victims per year have actually succeeded in obtaining a legal abortion.

Since 1996, Cemicamp, an NGO working in reproductive health and rights, has joined forces with women’s groups and with the Brazilian Federation of Obstetrical and Gynaecological Societies (FEBRASGO) to promote the provision of legal abortion services in public hospitals. In 1997, FEBRASGO created the National Scientific Commission on Sexual Violence and Legally Approved Abortion. The seal of approval that FEBRASGO gave to this initiative was highly significant for Brazilian obstetrician—gynaecologists. Cemicamp and the FEBRASGO Committee worked together to motivate obstetrician—gynaecologists and health authorities to establish clear procedures for implementing the existing abortion law, particularly for women victims of rape. The Ministry of Health officially sanctioned such procedures in 1998, and since then has joined forces with Cemicamp, FEBRASGO and the women’s rights movement in an effort to provide women access to legal abortion.Citation10 The number of public hospitals providing legal abortion services increased from four in 1995 to around 30 by December 2003. The key reason for this progress was the alliance formed between the medical establishment, the women’s rights movement and the political leadership of the federal government.

Several surveys have been carried out to collect information on the opinions of the Brazilian population with respect to the legal status of abortion. A recent poll that included a representative sample of the adult population (male and female) found that while over 50% agreed with the current law, 24% thought that abortion should be totally prohibited and only 10% were in favour of liberalising the law.Citation11 Several other studies with smaller, more local samples, but with more in-depth questions, found that most women and men were in favour of implementing current legislation to make abortion more easily accessible. In addition, most also favoured easier access to abortion in cases of severe fetal malformation, which is not permitted under the current law.Citation12, Citation13 A common finding of all studies was that the higher the level of education, the more liberal the opinion of Brazilians was with respect to abortion.Citation12 Citation13 Citation14

More recently, a number of women’s organisations launched an initiative called “Journey towards the Legalisation of Abortion” with the aim of making abortion legal. These organisations recognise the importance of strong social support with obstetrician—gynaecologists as allies.

In order to gather more information on the opinions and practice of these physicians with respect to abortion, we carried out a study of the knowledge, attitudes and practices of members of FEBRASGO to find out whether there is consistency between their public stance and their private decisions when they are confronted with an unwanted pregnancy at a personal level. This paper presents the data collected from this survey and discusses what we have learned.

Subjects and methods

The study was carried out in 2003 among obstetrician—gynaecologists affiliated to FEBRASGO. A structured questionnaire containing questions with coded answers for self-response was used. The questionnaire was pre-tested with four male and six female physicians in their first year of residency at the Women’s Hospital, State University of Campinas in São Paulo.

The questionnaire was sent to all 14,320 obstetrician—gynaecologists affiliated with FEBRASGO. We have no way of knowing how many of them actually received the questionnaire. The envelope contained: 1) the questionnaire, 2) a letter inviting them to participate in the study, with instructions on how to complete the questionnaire and send it back, 3) a code number to participate in a raffle of six palm-top computers and 4) a pre-paid envelope in which to return the questionnaire to the researchers.

The raffle was a small, additional incentive to participate. The code number identified the returned questionnaire but was detached immediately upon receipt and kept in a box until the raffle was drawn. The respondents kept a copy of the code number in order to claim the prize. However, there was no way for us to identify individual respondents and their anonymity was ensured.

Participation in the study was voluntary and anonymous. The letter inviting the physicians to participate explained the study, and contained information required by the Brazilian Ministry of Health.Citation17 By answering and returning the questionnaire, respondents understood they were consenting to participate. The research protocol was evaluated by the Ethical Committee on Research of the School of Medicine, State University of Campinas.

The envelope was inserted in the November/December 2002 issue of the Jornal da FEBRASGO, a monthly publication distributed to all FEBRASGO affiliates, which was circulated in late January 2003. It was included again in the January/February 2003 issue, distributed in late February, with instructions to discard it if the recipient had already completed and returned the questionnaire.

Questions included the age, sex and marital status of respondents, how many living children they had; the region in which they lived; the type of service in which they practised; the importance of their religious beliefs to their answers and their opinion regarding Brazil’s abortion law. A list of circumstances under which abortion could be legally permitted was provided, including the two situations approved by current legislation, and respondents were asked if they were in agreement with each one. Answers were classified according to the number of circumstances under which the respondents agreed abortion should be permitted. Physicians were also asked what they did when confronted with the unwanted pregnancy of a patient or a close relative, their own unwanted pregnancy (in the case of women) or that of their partner (in the case of men). The questions were phrased as follows:

| 1. | Consider the following situation: A patient of yours arrives at your office and tells you that she is pregnant and that she does not want to have the baby. Abortion is not legally permitted in her case. Even after you have counseled her to continue with the pregnancy, she still insists on having an abortion. What do you do? a) Help her have an abortion — send her to a physician who carries out abortions, teach her how to use misoprostol herself or carry out the abortion yourself or b) refuse to help her. | ||||

| 2. | Consider the following situation: a female member of your family arrives at your office and tells you that she is pregnant and that she doesn’t want to have the baby. Abortion is not legally permitted in her case. Even after you have counselled her to continue with the pregnancy, she still insists on having an abortion. What do you do? a) Help her have an abortion — send her to a physician who carries out abortions, teach her how to use misoprostol herself or carry out the abortion yourself or b) refuse to help her. | ||||

| 3. | If you are a woman: Have you ever had an absolutely unwanted pregnancy and felt that an abortion was necessary? What did you do? a) I have never had an unwanted pregnancy; b) I did have an unwanted pregnancy and had an abortion; c) I had an unwanted pregnancy but I did not have an abortion. | ||||

| 4. | If you are a man: Has a partner of yours ever had an absolutely unwanted pregnancy and felt that an abortion was necessary? What did she do? a) None of my partners has ever had an unwanted pregnancy; b) My partner had an unwanted pregnancy and had an abortion; c) My partner had an unwanted pregnancy but she did not have an abortion. | ||||

Between 10 February and 23 June 2003, 4,270 questionnaires were received, nine of them totally blank. This represented a 30% response rate. The questionnaires were numbered, reviewed and filed. Data entry was carried out in two separate data banks by two different people in order to check for consistency. SPSS softwareCitation15 was used to carry out data entry, to verify consistency and to analyse the answers. The chi-square test was used in all contingency tables,Citation16 and the significance level was set at 0.05.

Characteristics of the respondents

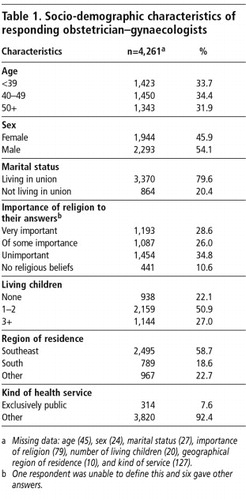

About a third of the 4,261 respondents were under 40 years of age, about 30% were 40—49 and the rest were over 49. There were slightly more men than women, and almost 80% were living in a stable relationship. About half had one or two living children, 27% had three or more children and just over 22% had no children ( ).

Almost 30% of respondents said their religious beliefs had had a very strong influence on their answers to the questionnaire, and most of them said that their religion did not approve of abortion. Around 60% were from the southeast of Brazil, less than 20% from the south and just over 20% from other regions, which is proportionally representative of the numbers of FEBRASGO members in each of these regions (58%, 15% and 27%, respectively). Less than 8% of the respondents were working exclusively in the public health service ().

Physician’s behaviour when confronted with an unwanted pregnancy

When a patient with an unwanted pregnancy requested help, 40.5% of the respondents said they helped the woman one way or another. The percentage of respondents who said they had helped the woman rose to 48.5% when the person requesting their help was a family member. The majority of those who helped a patient or family member did so by giving them the name or address of a colleague who was willing to carry out abortions (27.7% and 32.1%, respectively), a smaller proportion taught the woman how to use misoprostol (15.8% and 18.7%). Just 1.6% and 2.3% said they had carried out the abortion themselves.

Almost a quarter (22.6%) of the female physicians said they themselves had had at least one unwanted pregnancy and almost a third (31.8%) of the male physicians said one of their partners had done so. Almost 80% of these unwanted pregnancies were aborted, 77.6% among the female physicians and 79.9% among the partners of the male physicians (data not shown).

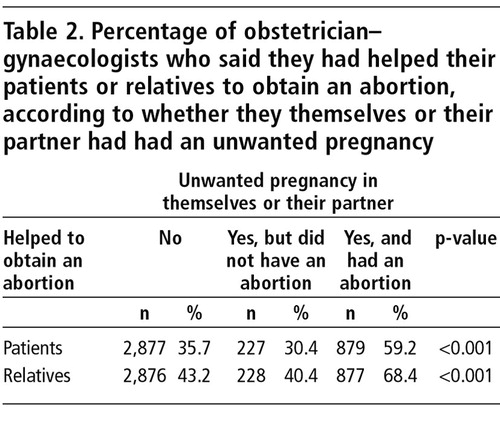

Around one third of physicians who had never experienced an unwanted pregnancy (35.7%) or who had experienced one but chose not to abort (30.4%) said they had helped a patient abort, and 40% and 43%, respectively, had helped a relative have an abortion. In contrast, among those physicians who had experienced an unwanted pregnancy that was aborted, almost 60% had helped a patient abort and 68% had helped relatives ( ).

Physician characteristics and behaviour when faced with an unwanted pregnancy

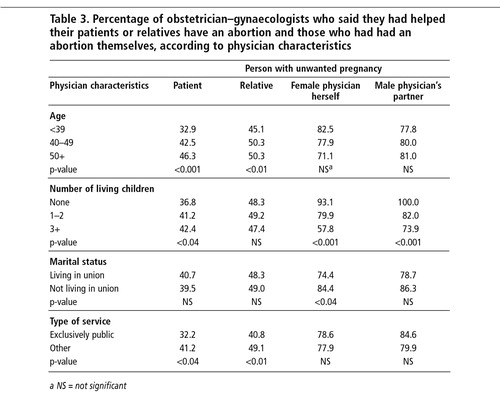

Younger respondents reported more conservative behaviour when confronted with the unwanted pregnancy of a patient or relative, but there were no significant differences according to age in the proportion who had had an abortion themselves (in the case of women) or whose partners had had an abortion (in the case of men) ( ).

The association between number of living children and how physicians responded when confronted with an unwanted pregnancy was significantly different depending on whose pregnancy it was. When the pregnancy was a patient’s, the physicians with more children were more favourable towards abortion than those with fewer children. There was no such association when the unwanted pregnancy was a relative’s. Yet, when the unwanted pregnancy was the physician’s or his partner’s, those with fewer children were more favourable towards abortion than those with more children ().

The physician’s marital status did not affect his/her behaviour when confronted with the unwanted pregnancy of a patient or relative. There was a higher incidence of abortion among the unmarried female physicians and the partners of the unmarried male physicians, although this difference did not reach statistical significance in the latter group ().

Physicians who worked exclusively in the public health service had a more conservative attitude when confronted with the undesired pregnancy of a patient or family member but there was no statistically significant difference between those in public service and those working in the private sector if they themselves or a partner had had an abortion ().

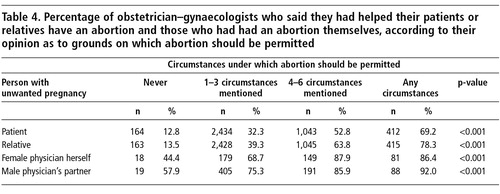

There was a very clear correlation between physicians’ opinions with respect to the grounds on which abortion should be permitted in Brazil and their declared behaviour when confronted with the unwanted pregnancy of a patient, a relative or their own unwanted pregnancy. The majority of physicians agreed that abortion should be permitted in cases of rape (76.6%) and risk to the woman’s life (79.3%), as per current legislation, and should be legal in cases of fetal malformation (77.0%). No other reason was approved by more than 20% of respondents (data not shown) However, even among those who believed abortion should not be permitted under any circumstances, about half said they or their partners had had an abortion when confronted with an unwanted pregnancy, although the number of respondents to whom this applied was small ( ).

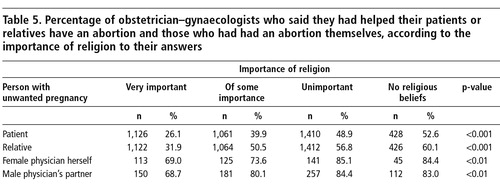

There was also a very clear correlation between the importance of religion to the respondents and their declared behaviour when confronted with an unwanted pregnancy, but this difference was much greater when it was a patient or relative who had an unwanted pregnancy. The proportion of physicians who helped patients or relatives abort was twice as high among those with no religious beliefs as among those for whom religion was very important. In contrast, when it was the physician herself or the physician’s partner with an unwanted pregnancy, the proportion who had an abortion reached almost 70% among those for whom religion was very important. Moreover, the proportion of physicians whose partner aborted an unwanted pregnancy was almost the same among those for whom religion was “of some importance” and those who had no religious beliefs (80% vs. 83%) ( ).

Discussion

The obstetrician—gynaecologists who responded to the questionnaire showed a progressive acceptance of the need for abortion the closer they were to the person with the unwanted pregnancy. Twice as many accepted that abortion was necessary when the unwanted pregnancy was their own or their partner’s as when it was a patient’s. Our findings suggest that physicians’ attitudes changed when the dilemma of undesired pregnancy affected them directly. However, even in the group of physicians who had personal experience of abortion, the proportion that helped patients or relatives to have an abortion was still below 60% and 70%, respectively.

Opposition to abortion weakens when the dilemma of an unwanted pregnancy affects the physician involved directly, probably because the physician realises there is no alternative. Even if they were strongly opposed to abortion, they may end up seeing the situation as “exceptional”. Sometimes, however, even after going through the experience personally, physicians may still remain firmly opposed to abortion.Citation18, Citation19 What they may not realise is that for each woman who has an abortion, the circumstances are exceptional, and only the woman herself can know how undesired a particular pregnancy is.

The results of this study seem to indicate that those who have been through the experience of terminating an unwanted pregnancy are more capable of understanding that the circumstances of others who want an abortion are also sufficiently exceptional as to justify helping them. On the other hand, those physicians who said they had had an unwanted pregnancy that was not aborted were more reluctant to help a patient or relative to obtain an abortion than physicians who had never experienced an unwanted pregnancy of their own or their partner’s. Even though they may have had strong religious or moral reasons for rejecting abortion, 30% of this group helped a patient, however, and 40% helped a relative obtain an abortion.

Younger respondents have had less time to be personally exposed to unwanted pregnancy, and this may be one reason why they were less willing than their older colleagues to help patients and relatives obtain an abortion.

It was interesting that a much higher proportion of physicians with no children had terminated an unwanted pregnancy than those with one or two children. This difference was even more pronounced when those with no children were compared to those with three children or more. It appears that those with no children had a stronger desire to control their reproductive capacity while, inversely, those with children were more willing to accept an additional child.

Differences according to marital status were not great, reaching statistical significance only with respect to a higher proportion of abortions among female physicians who were single than among those living in union. However, we do not know when the married female physicians had an abortion; it may have been when they were still single, thus limiting our ability to interpret these results.

A relatively small proportion of the respondents worked exclusively in the public sector. It is possible that poorer communication between physicians and patients in the public sector could be one explanation for the smaller percentage willing to help patients terminate an unwanted pregnancy compared to those in private practice. In addition, physicians in public service may be reluctant to trust patients to keep the matter confidential and may fear being accused of assisting an illegal act. That risk is much lower in private practice where the patient—physician relationship tends to be closer.

Better physician—patient communication may mean greater exposure of the physician to women’s personal histories of unwanted pregnancy. This may give them a better understanding of women’s dilemmas and help explain the greater willingness of physicians in private practice to help their relatives in this situation. The lack of a statistically significant difference between the percentage of physicians in public service and those in private practice who terminated their own unwanted pregnancy or their partner’s seems to indicate that personal experience in this situation is more important than any other factor.

The high correlation between the physicians’ stated opinions about the circumstances under which abortion should be permitted and the percentage of physicians who helped patients and relatives terminate a pregnancy is not surprising and reinforces the validity of these data. The percentage of respondents who helped patients and relatives abort was five to six-fold greater among those who believed that abortion should be permitted under any circumstances as compared to those who believed it should never be permitted. Differences were not that great, however, when comparing the percentage that terminated their partners’ or their own unwanted pregnancies. Indeed, almost 60% of those who declared that abortion should never be permitted under any circumstances had accepted the termination of an unwanted pregnancy by their partners, showing a clear discrepancy between their public stance against abortion and their behaviour when the problem was personal.

The difference in attitude to abortion according to the importance given to religion was not as large as expected. The percentage of physicians who helped a patient or relative terminate an unwanted pregnancy was about twice as high among physicians with no religious beliefs as among those for whom religion was of great importance. Moreover, even in the group of physicians for whom religion was of great importance, almost 70% of them or their partners had had an abortion, a mere 15 percentage points fewer than those physicians with no religious beliefs or for whom religion was not important.

The analysis of the data presented here supports the concept that understanding the dilemma of an unwanted pregnancy and accepting abortion as a legitimate solution to that dilemma is related to the proximity of the physician in question to the problem. The closer we are to the problem, the greater our ability and willingness to understand that there are circumstances under which abortion is the best acceptable alternative and that only the person most affected can judge whether it is the correct thing to do.

The limited proportion of FEBRASGO members who responded to the questionnaire, around 30%, limits the validity of the conclusions, as this sample may or may not be representative of the group as a whole. For example, those opposed to abortion may have been less likely to respond. The basic point raised by this study, however, is that willingness to accept abortion increases with the proximity of the physician to the problem, a correlation that was found regardless of the characteristics of the physicians who answered. If the physicians who did not answer were mostly those who are more influenced by religion, the difference in the proportion who have helped patients and relatives with an unwanted pregnancy or who themselves had an unwanted pregnancy and aborted will be even more pronounced than among those who gave less importance to religion.

It is relevant to recall that we are referring here to abortions that were all carried out clandestinely. As long as physicians believe that the majority of their colleagues oppose legislative changes, few will be willing to publicly give their support to the movement to reform the law. Knowing that the great majority of those who have been confronted with an unwanted pregnancy chose abortion shows that most physicians do accept abortion as a valid solution. This should weaken active opposition among obstetrician—gynaecologists to the legalisation of abortion in Brazil, but whether it will, remains to be seen. This study shows that obstetrician—gynaecologists who are in favour of making abortion legal are not a small minority, although they may not yet be ready to express their opinions publicly for fear of discrimination from their colleagues. Knowing than even those more influenced by religion personally resorted to abortion when confronted with an unwanted pregnancy provides strong moral support for others to openly express a favourable opinion regarding the legalisation of abortion. It is therefore our expectation that the presentation of these data will contribute towards the liberalisation of the currently restrictive abortion law in Brazil.

Acknowledgements

This research was partially financed by the Fundação de AmparoàPesquisa do Estado de São Paulo (FAPESP); Fundo de Apoio Ao Ensino e Pesquisa (FAEP) da Fundação para o Desenvolvimento da UNICAMP (FUNCAMP) and Ipas, USA. The authors translated the survey questions from the Portuguese.

References

- Alan Guttmacher Institute. Sharing Responsibility: Women, Society and Abortion Worldwide. 1999; AGI: New York.

- S Singh, D Wulf. Estimated levels of abortion in six Latin American countries International Family Planning Perspectives. 20: 1994; 4–13.

- D Gillespie. Making abortion rare and safe Lancet. 363: 2004; 74.

- VD Tsu. New and underused technologies to reduce maternal mortality Lancet. 363: 2004; 74.

- Organização das Nações Unidas. Relatório da ConferÁncia Internacional sobre População e Desenvolvimento. Cairo, 5—13 de setembro 1994.

- Organização das Nações Unidas. Plataforma de Ação da IV ConferÁncia Mundial da Mulher. Beijing, 4—15 de setembro 1995.

- Brasil Código Penal: decreto lei n0 2848 de 7/12/1940. 34a ed, 1996; Saraiva: São Paulo.

- JHR Torres. Aspectos legais do abortamento Jornal da Rede Saúde. 18: 1999; 7–9. At: http://www.redesaude.org.br/jornal/html/body_jr18-aspleg.html

- MIB da Rocha, J Andalaft Neto. A questão do aborto: aspectos clánicos, legislativos e politicos. E Berquó. Sexo & Vida — Panorama da Saúde Reprodutiva no Brasil. 2003; Editora da Unicamp: Campinas, 257–298.

- A Faúndes, E Leocádio, J Andalaft. Making legal abortion accessible in Brazil Reproductive Health Matters. 10(19): 2002; 120–127.

- IBOPE. Pesquisa de Opinião Pública sobre o Aborto. Brasil. Junho de 2003 OPP 075.

- MJD Osis, E Hardy, A Faúndes. Opinião das mulheres sobre as circunstâncias em que os hospitais deveriam fazer aborto Cadernos de Saúde Pública. 10: 1994; 320–330.

- GA Duarte, AT Alvarenga, MJD Osis. Perspectiva masculina acerca do aborto provocado Revista de Saúde Pública. 36(3): 2002; 271–277.

- JÁ César, G Gomes, BL Horta. Opinião de mulheres sobre a legalização do aborto em municápio de porte médio no Sul do Brasil Revista de Saúde Pública. 31(6): 1997; 566–571.

- SPSS for Windows: release 11.5. 2002; SPSS Inc: Chicago.

- DG Altman. Practical Statistics for Medical Research. 1991; Chapman & Hall/CRC: Boca Raton.

- Brasil Ministério da Saúde. Resolução 196/96 do Conselho Nacional de Saúde Informações Epidemiológicas do SUS. 5(2): 1996.

- M Bengtsson Agostino, V Wahlberg. Interruption of pregnancy: motives, attitudes and contraceptive use. Interviews before abortion at a family planning clinic, Rome Gynecologic and Obstetric Investigation. 32: 1991; 139–143.

- L Alvarez, CT Garcia, S Catasus. Abortion practice in a municipality of Havana, Cuba. AI Mundigo, C Indriso. Abortion in the Developing World. 1999; Vistar Publications: New Delhi, 117–130.