Abstract

Access to abortion services is not difficult in India, even in remote areas. Providers of abortion range from traditional birth attendants to auxiliary nurse midwives and pharmacists, unqualified and qualified private doctors, to gynaecologists. Despite a well-defined law, there is a lack of regulation of abortion services or providers, and the cost to women is determined by supply side economics. The state is not a leading provider of abortions; services remain predominantly in the private sector. Abortions in the public sector are free only if the woman accepts some form of contraception; other fees may also be charged. The cost of abortion varies considerably, depending on the number of weeks of pregnancy, the woman’s marital status, the method used, type of anaesthesia, whether it is a sex-selective abortion, whether diagnostic tests are carried out, whether the provider is registered and whether hospitalisation is required. A review of existing studies indicates that abortions cost a substantial amount — first trimester abortion averages Rs.500—1000 and second trimester abortion Rs.2000—3000. Given the number of unqualified providers and with 15-20% of maternal deaths due to unsafe abortions, the costs of unsafe abortions must also be counted. It is imperative for the state to regulate the abortion economy in India, both to rationalise costs and assure safe abortions for women.

Résumé

L’accès aux services d’avortement n’est pas difficile en Inde, mÁme dans les régions reculées. Les avortements sont pratiqués par des accoucheuses traditionnelles, des infirmières accoucheuses assistantes et des pharmaciens, des médecins privés qualifiés ou non qualifiés et des gynécologues. Malgré une législation précise, une réglementation des services d’avortement ou de l’habilitation des praticiens fait défaut, et le co t de l’avortement est déterminé par l’offre. L’Átat n’est pas un prestataire majeur ; les services relèvent en majorité du secteur privé. Dans le secteur public, l’avortement n’est gratuit que si la femme accepte une contraception ; d’autres frais peuvent Átre facturés. Le prix de l’avortement varie considérablement, selon le nombre de semaines de grossesse, l’état civil de la femme, la méthode et l’anesthésie utilisées, s’il s’agit d’un avortement pour sélectionner le sexe de l’enfant, si des tests de diagnostic sont pratiqués, si le praticien est enregistré ou si une hospitalisation est nécessaire. Les études disponibles indiquent que les avortements sont chers — pendant le premier trimestre en moyenne Re 500—1000 et Re 2000—3000 au deuxième trimestre. Átant donné le nombre de praticiens non qualifiés et avec 15—20% de décès maternels dusàdes avortements non médicalisés, il faut aussi tenir compte du co t des avortementsàrisque. Il faut que l’Átat régule le secteur de l’avortement en Inde, pour rationaliser les co ts et garantir des avortements s rs.

Resumen

En la India no es difácil tener acceso a los servicios de aborto, aun en las zonas remotas. Los prestadores de servicios de aborto son desde parteras, enfermeras-obstetrices auxiliares y farmacéuticos, hasta médicos privados, calificados o no, y ginecólogos. A pesar de existir una ley bien definida, no se regulan los servicios de aborto o los prestadores de éstos, y el costo para las mujeres es determinado por la economáa de la oferta. El estado no es un prestador principal de servicios de aborto, los cuales presta predominantemente el sector privado. Los abortos en el sector público son gratuitos sólo si la mujer acepta algún tipo de anticoncepción; es posible que le cobren otras tarifas. El costo del aborto varáa considerablemente, conforme a la edad gestacional, estado civil de la mujer, método utilizado, tipo de anestesia, si es un aborto por selección del sexo, si se efectúan pruebas diagnósticas, si el prestador está inscrito y si se requiere hospitalización. Una revisión de los estudios disponibles indica que el aborto tiene un costo considerable: el valor promedio de un aborto en el primer trimestre es de Rs.500—1000 y en el segundo trimestre de Rs.2000—3000. Dado el número de prestadores no calificados y que del 15 al 20% de las muertes maternas se atribuyen al aborto inseguro, también se deben contar sus costos. Es imperativo que el estado regule la economáa del aborto en la India, tanto para racionalizar los costos como para garantizar la prestación de servicios de abortos seguros a las pacientes.

Access to abortion services of a wide-ranging variety is not difficult in India, even in the remotest areas of the country. The assortment of providers of abortion services ranges from dais (traditional birth attendants) and herbalists to government paramedics such as auxiliary nurse midwives, pharmacists and other health workers, unqualified private providers, qualified but uncertified doctors to gynaecologists.Footnote* This is despite the fact that the practice of abortion has been legal since 1971 when carried out only by those certified under the Medical Termination of Pregnancy Act. With certification available under the Act to all allopathic doctors who meet the requirements and with no dearth of providers who can be certified, even so, unregistered and illegal abortions continue to take place in overwhelmingly large numbers. Why?

The answer lies in the political economy of modern health care in India and specifically abortion care. Traditionally, birth attendance and abortion were very much in the domain of the local dai or an equivalent practitioner, such as a herbalist. Usually a woman, this provider was part of the jajmani Footnote* relations and provided services to all within the community she lived in. Not much has been published about abortion in pre-colonial India, but there is no evidence of abortion being illegal, notwithstanding Kautilya’s Arthashastra, which specified severe punishment for aborting a slave woman.Citation1 In fact, the code of ethics as per Charaka Samhita does not mention abortion, unlike in the Hippocratic oath (“I will not give a pessary to a woman to produce abortion”).Citation2

Role of the state in India’s abortion law and provision

A ban on abortion came into effect only with the establishment of the Indian Medical Service in 1763 (initially as the Bengal Medical Service) under the British.Citation3 This was codified in the Indian Penal Code of 1860 and criminalisation was maintained in the code of ethics of the Indian Medical Council, established in 1956 (“I will maintain the utmost respect for human life from the time of conception”). Criminalisation threatened traditional dispensation; however, given that regulation of medical practice was grossly wanting, abortion services continued to thrive during this period.

Hence, it was not a priority for feminists and women’s organisations to struggle for legal abortion, as elsewhere in the world. The Indian government, in its tenacious pursuit of population control, adopted abortion as one more method of fertility control and legalised abortion under the Medical Termination of Pregnancy (MTP) Act, 1971. Legalisation potentially provided the medical profession with a monopoly over abortion and a means to medicalise it. Legal abortion services began to expand but did not significantly threaten traditional abortion providers. On the contrary, abortion was seen as a growing business and many medical practitioners, unqualified and untrained in abortion, entered the fray. Since regulation of medical practice remained weak, this put a damper on the expansion of legal services.

The state has not become a leading provider of abortions, as it did with family planning services, especially sterilisation. Instead, abortion services have remained predominantly in the private sector. The state has played a more subtle role, keeping abortion within the family planning context by providing subsidies to select private abortion providers if they make abortion provision dependent on acceptance of sterilisation or an IUD. Organisations like the Family Planning Association of India (FPAI) and many other NGOs get grants for doing sterilisations and inserting IUDs, including money to give to women as an incentive, and often this is linked to abortion services, which are provided free to acceptors of contraception. For instance, the records of FPAI reveal that 97% of abortions in 2001—02 in Delhi were associated with sterilisation or an IUD.Citation4 The state pushed hard for this programmatic result, but the consequence was that women turned away from the limited public health facilities for abortion.

An unmet demand for public abortion services and the lack of any effective regulatory mechanisms further opened the floodgates for all sorts of private providers, unqualified persons, non-allopathic doctors and paramedics. In the 1980s, there were huge advertising campaigns by private providers selling abortion services “for Rs.70 only”. This gave a clear message on the part of the state that abortion could be practised freely irrespective of the restrictions in the MTP Act, adding to the number of illegal and unsafe abortion providers. The first major study on illegal abortions in rural areas by the Indian Council for Medical Research (ICMR), published in 1989, showed that 68.5% of all induced abortions were illegal. This study of 44,731 pregnancy outcomes, conducted in five states, found an induced abortion ratio of 21 per 1,000 live births. Induced abortions constituted 1.98% of all pregnancy outcomes.Citation5

At the same time, medicalisation has meant that traditional abortion methods have been marginalised and traditional providers, if they have not stopped practising altogether, have either adopted more modern methods or become agents of modern abortion providers by referring cases to them. Sterilisation has also gained wide acceptance in the rural areas and is being done at increasingly lower ages (mean age in 2004 was 28 years in contrast to just under 35 years a decade before).Citation6 Thus, the demand for abortion was partially affected, affecting traditional providers in turn, who only survive in remote pockets, adivasi (tribal) areas and other underserved areas.

Of concern, in terms of safe abortion services, are the growing number of non-traditional but unqualified practitioners on the one hand, and the lack of ethics and self-regulation among qualified professionals and their associations on the other.

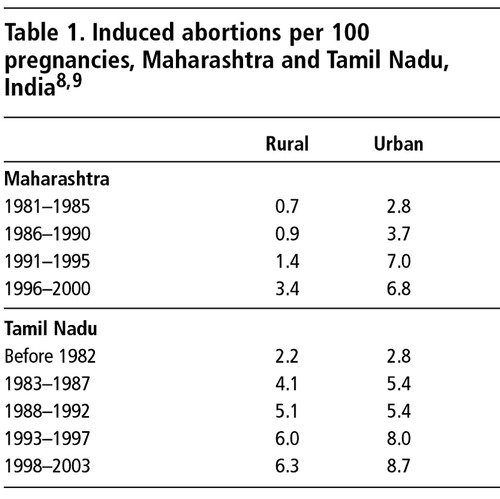

Today, sex-selection and sex-determination possibilities have catapulted the abortion business to new heights, and many unscrupulous players have entered the scene. Abortion rates have seen an upswing in the last decade. Since abortion data are not easy to come by, most of the evidence is anecdotal and comes from states which have seen a major decline in child sex ratios during the inter-census periods 1981—1991 and 1991—2001.Citation7 A recent study in Maharashtra and Tamil Nadu, under the aegis of the Abortion Assessment Project — India, which collected data on pregnancy outcomes from a large random sample spread across all districts of the respective states, provides more direct evidence of increased rates of induced abortion in both urban and rural areas from 1981 onwards, in a period which saw the promotion of the two-child population policy, increased acceptance of family planning as a legitimate practice and at the same time, an increase in sex selection (See ).Citation8, Citation9 The massive decline in child sex ratios awakened the state to the need to put some regulations in place. The Pre-Natal Diagnostic Techniques Act (effective 1996) has been strengthened to control sex selection. Then, in 2002, the MTP Act was also amended to make the process of certification of abortion providers and registration of abortion clinics simpler and less bureaucratic in the hope that the proportion of legal abortions would increase substantially.

Cost of abortion from studies of clinic charges

In India, data on charges for abortion are not available except in small studies of providers and household-based studies researching health care utilisation patterns. A review of existing studies indicates that first trimester abortion is mostly available for Rs.500—1000 and second trimester abortion for Rs.2000—3000.

A study of abortion providers in Delhi in 2002 found that the cost of abortions varied considerably, depending on the number of weeks of pregnancy, the abortion method used, the woman’s marital status, type of anaesthesia, whether acceptance of contraception was involved, whether it was a sex-selective abortion, whether any diagnostic tests (e.g. pregnancy test, sonography, laboratory tests) were carried out, medications given, location of the clinic, whether the provider was certified and the clinic registered, whether hospitalisation was required, and the nature of the competition. Thus, private nursing homes and clinics that charged a married women Rs.400—600 for a first trimester abortion were charging Rs.1200 if the woman was unmarried or even higher if anaesthesia was used. In cases where anaesthesia was used, the cost was two to three times higher for general anaesthesia than local. Second trimester abortions cost up to 3—4 times more than first trimester.Citation4 The following factors were shown in other studies to influence the amount.

Lack of government regulation

In the absence of regulation of India’s health care system, and since health insurance in India does not normally cover abortions, the pricing of abortion services remains unregulated. For all these reasons, and given the stigma and secrecy that often accompany abortions, the cost to women is likely to be determined by supply side economics. Only social insurance programmes that do cover abortions, such as the Employees State Insurance Scheme, Central Government Health Scheme, Mines and Plantations Acts and Maternity Benefit Act, have fixed rates which are reimbursed for the small population with such cover.Citation4

Public vs. private sector

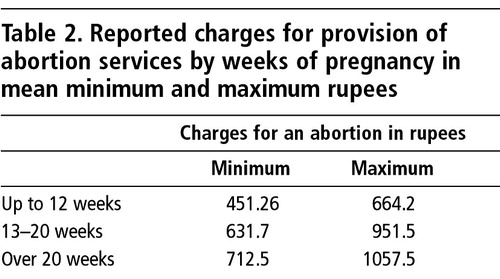

Recently, a multicentre study in six states in India in 2001—2002 attempted to obtain charges from private and public providers of abortion services. The providers were asked to report the minimum and maximum amounts they charged their patients at different stages of pregnancy. These data are summarised in , and show the expected trajectory of increasing charges as pregnancy progresses.Citation10

In the public sector, abortion services are usually free, but in recent years some states have introduced user fees or have allowed private practice by public providers. Hence, such charges were being reported in the six-state study. Further, in some states, even if abortion services per se are free, there is a policy of charging for the abortion if a family planning method is not also accepted by the woman. Overall in the six states, the average charges for an induced abortion were Rs.615. This is equivalent to more than three weeks of average per capita income for all-India. The overall charges in the public sector averaged Rs.115 (or four days of per capita income) and in the private sector Rs.801 (or 30 days of per capita income). Public providers were the least expensive, and among the private providers, the certified ones were charging substantially higher fees than the uncertified ones.31

A number of other studies in the last few years have also looked at what clinics charge or what women pay for abortion services. The Centre for Operations Research and Training conducted studies of providers in rural Uttar Pradesh, Maharashtra, Gujarat and Tamil Nadu between 1995 and 1997. The clinic charges for an abortion ranged from Rs.135—534 (average Rs.370) for public providers and Rs.394—649 (average Rs.497) for private providers. Of these, the doctors got an average of 42% and 21% was spent on medicines, the rest being for hospital charges like operating theatre and bed charges.Citation11 A similar study in Maharashtra in 1999 computed the average cost of abortion at Rs.991,Citation12 and another in Uttar Pradesh and Rajasthan in 1998 found the average cost was Rs.200—500 in a public facility, Rs.700—800 in private hospitals and Rs.1000 or more in the Marie Stopes clinics.Citation13

Abortion method and reason for abortion

Vacuum aspiration cost much less than dilatation and curettage (D&C), since the latter uses general anaesthesia, which adds to the cost. Manual vacuum aspiration (MVA) use is still very low in India but all the evidence from other developing countries supports an expansion in the use of MVA, not only because it is less costlyCitation14 but also because it is safer and can be done by trained paramedics, and would encourage earlier abortions.Citation15

Another reason for cost variation is related to sex-selective abortions, presumably because sex determination tests are illegal. A qualitative study of women who had had abortions in Maharashtra showed that while most abortions cost Rs.100—1200, depending on whether it was a public or private facility, the cost went up to Rs.5000 for a sex-selective abortion in a private facility.Citation16

Cost of abortion from household studies

Some data on out-of-pocket expenditure have been collected at the household level from women who have had abortions; however, national level studies like the National Family Health Survey, Reproductive and Child Health survey and the health surveys of the National Sample Survey Organisation have failed to collect such data when recording pregnancy outcomes, and only a few small studies exist. In public budgets, abortion-related expenditure is not a budget line or indicated separately, except when there is a specific scheme for upgrading of services or other such provision. For instance, in the Maharashtra health budget of 2001—02, the sum of Rs.2.23 million was allocated under the Maternal & Child Health Programme for expansion of abortion services, and in 2003—04, the amount was Rs.2.5 million.Citation17

An early study on health expenditures in 1987, which included abortion, found that the mean expenditure for an induced abortion was Rs.300, of which 41% went to the doctor and hospital and as much as 36% for medicines and tonics. The share of abortion expenditure in total out-of-pocket household health expenditure was 0.21%.Citation18

A similar study in 1990 found that the mean expenditure for induced abortion was Rs.1,258, which was 0.54% of total out-of-pocket household health expenditure.Citation19 More recently, two studies on women’s reproductive health by the Centre for Enquiry into Health and Allied Themes recorded mean expenditure for a public sector induced abortion as Rs.640Citation20 and private as Rs. 989.Citation21 In these two studies the share of abortion in total out-of-pocket household health expenditure was 0.16% in 2000 and 0.28% in 2001, respectively.

A study in West Bengal in 1998 calculated median expenditures by women for each induced abortion as follows: in private hospitals and nursing homes Rs.1000; private clinics Rs.500; government hospitals Rs.356; primary health centres Rs.335; rural medical practitioners (unqualified) Rs.400; and traditional healers Rs.200.Citation22

In Rajasthan a large study in 1998—99 using the national health accounts framework estimated expenditures on abortion state-wide for both public and private health sectors.Citation23 This study found that mean out-of-pocket household expenditure for an abortion was Rs.925, with a small public—private variation — for government services Rs.873 and for private services Rs.977. This study estimated the value of the entire health economy of Rajasthan at Rs.30,034 million in 1998—99 with the public sector share being 29% (Rs.8,673 million). The health expenditure thus amounted to 5.95% of the state domestic product, with the private sector accounting for 4.23% of state domestic product. Of this the Reproductive and Child Health Programme expenditure (maternity, immunisations, antenatal and post-natal care, abortions, contraception, etc) was Rs.6,424 million, and of the latter abortion was Rs.160 million. Thus, the share of abortion worked out to 0.53% of total health expenditure. Out of the total abortion expenditure, 82.5% (Rs.132 million) was out-of-pocket expenditure and the rest was spent by the public health sector. In the public sector the share of abortion in total health expenditure worked out to 0.32% and in the private sector 0.62%.

As part of the Abortion Assessment Project — India, household level studies were carried out in Maharashtra and Tamil Nadu which suggest that during 1996/97-2001/02 the median expenditure incurred by women was Rs.1,220 in MaharashtraCitation8 and Rs.950 in Tamil Nadu.Citation9

Cost of medical abortion: pharmaceutical estimates

In recent years, medical abortion (mifepristone + misoprostol, or misoprostol alone) has begun to be used widely across the world. Its use in India was approved in February 2002 by the Drugs Controller. An article in IMS Health, August 2003, estimated that mifepristone sales in India were about Rs.174 million over the previous 12 months (at Rs.320 per abortion this translates into 540,000 medical abortions).This is likely to be an underestimate because there has been a grey market for several years now, and the drugs are available over the counter in many places.

Discussion

Abortion economics in India thus has specific peculiarities. Despite early legalisation of abortion the problem of illegal providers and unsafe abortion looms large. This translates into a political economy of abortion which is controlled by providers, with those who are unqualified and unregistered exploiting the vulnerability of women seeking abortion and contributing to widespread post-abortion problems and mortality. This does not imply that those qualified and certified do not exploit women as well, but at least the latter are open to monitoring by the authorities.

The responsibility for this mismanaged political economy falls squarely on both the state agencies and qualified medical professionals. The former because they have failed miserably in public provision of safe abortion services and have not regulated private abortion providers. For example, all primary health centres (PHCs) and rural hospitals (one facility per 20,000 population) are registered automatically to provide abortion services. Yet according to the government’s own study,Citation24 the Reproductive and Child Health Facility Survey Phase I, only 13% of PHCs and 28% of rural hospitals had health personnel certified to do abortions. The medical professionals are equally to blame because they lack ethical medical practice and have failed to self-regulate professional conduct. When viewed in conjunction with the social dynamics leading to unwanted pregnancies and the social restrictions in access which women face,Citation16 India has a political economy of abortion that thrives on the vulnerabilities of those who are the source of providers’ income and survival.

Analysis of expenditure data shows that women have to spend substantial amounts to access both private and public abortion services. Public abortion services until recently were free of charge even though women reported out-of-pocket expenses (usually non-medical expenses like travel or prescription drugs). At present, abortion services in the public sector are free only if the woman or her husband accepts some form of contraception, usually sterilisation or an IUD, after the abortion. This conditionality existed even prior to user fees being introduced in 2000 and was the main reason why women stopped coming to public health facilities for abortions. The addition of user fees made access to public abortion services even more remote. In the private sector, the cost of an abortion represents a substantial expense for the poor and even for lower middle-class women.

Given that a large number of providers are unqualified to do abortions, the cost of unsafe abortions must also be factored in. Post-abortion costs due to botched abortions and complications could be high. This is an unexplored area in abortion economics even though about 13% of maternal deaths are due to unsafe abortions. Another dimension in abortion economics, especially related to the private sector, relates to the methods used for abortion. The insistence on curettage even for very early abortion, and so-called check curettage after vacuum aspiration, is widespread amongst both certified and non-certified providers, adding to the cost as well the risk of post-abortion infections and other problems. This is evident from recent studies undertaken under the aegis of the Abortion Assessment Project — India.Citation10

This review shows that it is imperative for the state to regulate the abortion economy in India, both services and the medical profession, in order to rationalise costs and assure safe abortions for women. It would make good sense to expand the base of certified and registered abortion providers to include nurses, midwives and auxiliary nurse—midwives to provide early abortion services, as it would eliminate many of the quacks. This is more easily said than done because it will involve large-scale investment in training, strong resistance from the medical profession, require strengthening of support systems in public health services and a change in the state’s perspectives on abortion. However, such an option in terms of financing would be cost-effective and simultaneously could help to increase the credibility of the public health system and rebuild women’s willingness to use public abortion services.

Acknowledgements

This is a modified version of a paper entitled “Abortion economics”, originally published in Seminar 2003;532(December):47—52, and published here with kind permission of Seminar.

Notes

* The term “qualified” refers to practitioners who have a medical qualification recognised under law; the term “certified” refers to having a license to practice abortion under the MTP Act; the term “registered” refers to abortion centres that have been given a license to operate under the MTP Act and to abortions at such centres.

* The jajmani system was a set of economic inter-relations across caste groups in the local community which had social sanction and was linked to mandatory social obligations. This also kept intact the economic basis of the caste system. Today it is largely destroyed but may be found in pockets in most states, especially the Hindi heartland.

References

- O Jaggi. Indian System of Medicine. 1981; Atma Ram and Sons: Delhi.

- O Jaggi. Western Medicine in India: Social Impact. 1980; Atma Ram and Sons: Delhi.

- D Crawford. A History of Indian Medical Service 1600-1913. 1914; W Thacker and Co: Calcutta.

- R Sundar. Abortion Costs and Financing: A Review. 2003; CEHAT and Healthwatch: Mumbai.

- Indian Council of Medical Research. Illegal Abortions in Rural Areas. 1989; ICMR: New Delhi.

- Government of India. Family Welfare Year Book 2001. 2003; Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, GOI: New Delhi.

- Government of India. Census 2001 Final Population Totals. 2002; Census Commissioner: New Delhi.

- S Saha, R Duggal, M Mishra. Abortion in Maharashtra: Incidence, Care and Cost. 2004; CEHAT: Mumbai.

- S Krishnamoorthy, N Thenmozhi, J Sheela. Pregnancy Outcome in Tamil Nadu. 2004; Bharatihar University: Coimbatore.

- R Duggal, S Barge. Abortion Services in India: Report of a Multicentric Enquiry. Abortion Assessment Project — India. 2004; CEHAT and HealthWatch: Mumbai.

- Khan ME, Rajagopal S, Barge S, et al. Situational analysis of medical termination of pregnancy services in Gujarat, Maharashtra, Tamil Nadu and Uttar Pradesh. Paper presented at International Workshop on Abortion Facilities and Post-Abortion Care and Operations Research. New York, 19—21 January 1998.

- S Bandewar, M Sumant. Quality of Abortion Care: A Reality. 2002; CEHAT: Pune.

- Parivar Seva Sanstha. Abortion Research Phase II Final Report. 2002; PSS: New Delhi.

- M Jowett. Safe motherhood intervention in low income countries: an economic justification and evidence of cost effectiveness Health Policy. 53(3): 2000.

- B Klugman, D Budlender. Advocating for Abortion Access. 2000; University of Witwatersrand: Johannesburg.

- M Gupte. Abortion needs of women in India: a case study of rural Maharashtra Reproductive Health Matters. 5(9): 1997.

- Government of Maharashtra. Civil Budget 2003—04 - Public Health Department. 2003; GOM: Mumbai.

- R Duggal, S Amin. Cost of Health Care. 1989; Foundation for Research in Community Health: Mumbai.

- A George. A Study of Household Health Expenditure in Madhya Pradesh. 1992; FRCH: Mumbai.

- N Madhiwala. Health Households and Women’s Lives. 2000; CEHAT: Mumbai.

- S Nandraj. Women and Healthcare in Mumbai. 2001; CEHAT: Mumbai.

- Mathai S. Study on prevalence of abortion in West Bengal. (Unpublished)

- Indian Institute of Health Management and Research. Financing Reproductive and Child Health Care in Rajasthan. 2000; IIHMR: Jaipur.

- Government of India. Reproductive and Child Health Facility Survey. 2002; International Institute of Population Sciences: Mumbai.