Abstract

Despite 30 years of liberal legislation, the majority of women in India still lack access to safe abortion care. This paper critically reviews the history of abortion law and policy in India since the 1960s and research on abortion service delivery. Amendments in 2002 and 2003 to the 1971 Medical Termination of Pregnancy Act, including devolution of regulation of abortion services to the district level, punitive measures to deter provision of unsafe abortions, rationalisation of physical requirements for facilities to provide early abortion, and approval of medical abortion, have all aimed to expand safe services. Proposed amendments to the MTP Act to prevent sex-selective abortions would have been unethical and violated confidentiality, and were not taken forward. Continuing problems include poor regulation of both public and private sector services, a physician-only policy that excludes mid-level providers and low registration of rural compared to urban clinics; all restrict access. Poor awareness of the law, unnecessary spousal consent requirements, contraceptive targets linked to abortion, and informal and high fees also serve as barriers. Training more providers, simplifying registration procedures, de-linking clinic and provider approval, and linking policy with up-to-date technology, research and good clinical practice are some immediate measures needed to improve women’s access to safe abortion care.

Résumé

Après 30 ans de législation libérale, la majorité des Indiennes n’a toujours pas accèsàdes avortements s rs. L’article retrace l’histoire de la loi et la politique sur l’avortement en Inde depuis les années 60 et la recherche sur ces services. Des amendements en 2002 et 2003àla Loi de 1971 sur l’interruption médicale de grossesse — notamment le transfert aux districts de la réglementation des services, des mesures punitives pour décourager les avortements clandestins, la rationalisation des équipements pour pratiquer des avortements précoces, et l’homologation de l’avortement médical — visaientàrendre les services plus s rs. Des amendements pour prévenir les avortements sélectifs selon le sexe du fætus, contrairesàl’éthique etàla confidentialité, n’ont pas été adoptés. Des problèmes chroniques restreignent l’accès, par exemple l’insuffisante réglementation des services publics et privés, une politique du « tout médical », qui exclut les prestataires intermédiaires, et le faible niveau d’homologation des dispensaires ruraux par rapport aux dispensaires urbains. D’autres freins sont l’ignorance de la loi, l’obligation superflue d’obtenir le consentement du conjoint, des objectifs contraceptifs liésàl’avortement et les co ts élevés. Pour élargir l’accèsàdes soins s rs, il faut former davantage de prestataires, simplifier les procédures d’enregistrement, séparer l’homologation des dispensaires et des prestataires, et associer la politique avec une technologie moderne, des recherches et une bonne pratique clinique.

Resumen

Pese a 30 años de legislación liberal, la mayoráa de mujeres en la India aún carecen de acceso a servicios de aborto seguro. En este artáculo se revisa la historia de la ley de aborto y las poláticas pertinentes desde los sesenta, y las investigaciones sobre la prestación de servicios de aborto. Las enmiendas del 2002 y 2003 a la Ley de Interrupción Médica del Embarazo de 1971, incluida la devolución de la regulación de los servicios al nivel distrital, las medidas punitivas para obstaculizar la práctica de abortos inseguros, la racionalización de los requisitos fásicos para que se practiquen abortos en etapas iniciales, y la aprobación del aborto farmacológico, han procurado ampliar los servicios. Las enmiendas propuestas a la ley contra el aborto por selección del sexo no hubiesen sido éticas y hubieran violado la confidencialidad; por tanto, no se llevaron a cabo. Entre los problemas constantes figuran la regulación deficiente de servicios en los sectores público y privado, la polática “sólo médicos” que excluye a los profesionales de la salud de nivel intermedio, y un bajo registro de las clánicas rurales en comparación con las urbanas; han limitado el acceso. Otras barreras son: poco conocimiento de la ley, requisitos innecesarios de consentimiento del cónyuge, blancos anticonceptivos vinculados al aborto y tarifas altas extraoficiales. El capacitar más proveedores, simplificar el registro, desvincular a la clánica de la aprobación del proveedor y vincular las poláticas con tecnologáa actualizada, la investigación y las buenas prácticas clánicas son algunas medidas inmediatas necesarias para mejorar el acceso de las mujeres a los servicios de aborto seguro.

The Indian Penal Code 1862 and the Code of Criminal Procedure 1898, with their origins in the British Offences against the Person Act 1861, made abortion a crime punishable for both the woman and the abortionist except to save the life of the woman. The 1960s and 70s saw liberalisation of abortion laws across Europe and the Americas which continued in many other parts of the world through the 1980s.Citation1, Citation2 The liberalisation of abortion law in India began in 1964 in the context of high maternal mortality due to unsafe abortion. Doctors frequently came across gravely ill or dying women who had taken recourse to unsafe abortions carried out by unskilled practitioners. They realised that the majority of women seeking abortions were married and under no socio-cultural pressure to conceal their pregnancies and that decriminalising abortion would encourage women to seek abortion services in legal and safe settings.Citation3

The Shah Committee, appointed by the Government of India, carried out a comprehensive review of socio-cultural, legal and medical aspects of abortion, and in 1966 recommended legalising abortion to prevent wastage of women’s health and lives on both compassionate and medical grounds.Citation4 Although some States looked upon the proposed legislation as a strategy for reducing population growth,Citation5 the Shah Committee specifically denied that this was its purpose. The term “Medical Termination of Pregnancy” (MTP) was used to reduce opposition from socio-religious groups averse to liberalisation of abortion law. The MTP Act, passed by Parliament in 1971, legalised abortion in all of India except the states of Jammu and Kashmir.

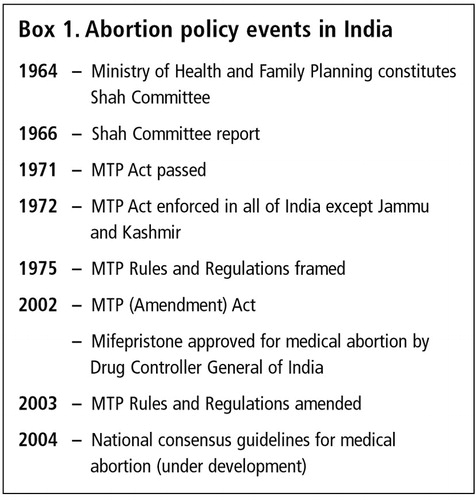

Despite more than 30 years of liberal legislation, however, the majority of women in India still lack access to safe abortion care. This paper critically reviews the history of abortion law and policy reform in India (Box 1), and epidemiological and quality of care studies since the 1960s. It identifies barriers to good practice and recommends policy and programme changes necessary to improve access to safe abortion care.

The Medical Termination of Pregnancy Act 1971 and Regulations 1975

The MTP Act (No.34 of 1971)Citation6 confers full protection to a registered allopathic medical practitioner against any legal or criminal proceedings for any injury caused to a woman seeking abortion, provided that the abortion was done in good faith under the terms of the Act. The Act allows an unwanted pregnancy to be terminated up to 20 weeks of pregnancy, and requires a second doctor’s approval if the pregnancy is beyond 12 weeks. The grounds include grave risk to the physical or mental health of the woman in her actual or foreseeable environment, as when pregnancy results from contraceptive failure, or on humanitarian grounds, or if pregnancy results from a sex crime such as rape or intercourse with a mentally-challenged woman, or on eugenic grounds, where there is reason to suspect substantial risk that the child, if born, would suffer from deformity or disease. The law allows any hospital maintained by the Government to perform abortions, but requires approval or certification of any facility in the private sector.

In the event of abortion to save a woman’s life, the law makes exceptions: the doctor need not have the stipulated experience or training but still needs to be a registered allopathic medical practitioner, a second opinion is not necessary for abortions beyond 12 weeks and the facility need not have prior certification.

The Medical Termination of Pregnancy Rules and Regulations 1975Citation7 define the criteria and procedures for approval of an abortion facility, procedures for consent, keeping records and reports, and ensuring confidentiality. Any termination of pregnancy done at a hospital or other facility without prior approval of the Government is deemed illegal and the onus is on the hospital to obtain prior approval.

Abortion in India 1970—2000

The initial years from 1972 to 1986 after legalisation of abortion showed only a marginal increase (8—10%) in the number of approved abortion facilities and the number of abortions reported by those facilities. In contrast, the late 1980s and 90s showed a declining trend in the number of abortions reported in approved facilities.Citation6 In 1997, some two-thirds of approved facilities were urban-based clinics, reflecting ongoing serious inequity in urban vs. rural access to approved abortion facilities in a still predominantly rural country.Citation8 In the mid-1990s, less than 10% of the estimated total number of abortions were reported to the government.Citation9 Citation10 Citation11 Data on abortions occurring outside approved facilities are rare and unreliable. Estimates dating from the beginning of the 1990s to more recent years are largely speculative and have ranged from 2—11 illegal abortions performed for every legal abortion.Citation3, Citation12, Citation13

Thus, although it may not be the case that abortions in unapproved facilities are all unsafe, it can still be assumed that safe abortion care is still not widely available. In most states, less than 20% of primary health centres provide abortion services.Citation14, Citation15 Even where they do so, women prefer to seek abortion in the private sector, leading to under-utilisation of public facilities. Further, the quality of abortion services in both the public and private sectors is often poor in terms of technique used, counselling, privacy and confidentiality. The majority of doctors still prefer dilatation and curettage (D&C) for early abortion, with less than a quarter of providers reportedly using vacuum aspiration.Citation8, Citation16 Awareness of the legality of abortion is low and misconceptions about the law among women and providers are prevalent. Citation17 Citation18 Citation19 Citation20 Citation21

Abortion law reform since 2000

India has committed itself to safeguarding human and reproductive rights articulated in various international forums.Citation22 Citation23 Citation24 Citation25 After a long consultative process involving various governmental and non-governmental agencies, professional bodies and activists, the Indian Parliament enacted the Medical Termination of Pregnancy (Amendment) Act 2002 and amended Rules and Regulations 2003.Citation26, Citation27

In an effort to reduce the bureaucracy for obtaining approval of facilities, the new Act decentralised regulation of abortion facilities from the State level to District Committees that are empowered to approve and regulate abortion facilities. It also provides punitive measures of 2—7 years imprisonment for individual providers and owners of facilities not approved by or maintained by the Government. To reduce administrative delays, the amended MTP RulesCitation27 define a time frame for registration and mandate the District Committee to inspect a facility within two months of receiving an application for registration and process the approval within the next two months if no deficiencies are found, or within two months after rectification of any noted deficiency. However, the amended MTP Rules do not specify measures to be taken if approval procedures are still not completed in the stipulated time frame.

While physical standards for a facility providing second trimester abortions remain the same (operating table, abdominal or gynaecological surgery equipment, Boyle’s apparatus for general anaesthesia, autoclave, drugs and supplies for emergency resuscitation) the amended MTP Rules rationalise the physical standards required for first trimester abortions. Facilities are no longer required to have on-site capability of managing emergency complications. However, every facility needs to have personnel trained to recognise complications and provide or be able to refer women to facilities capable of emergency care.

The amended MTP Rules also recognise medical abortion methods and allow a registered medical practitioner (e.g. the family physician) to provide mifepristone + misoprostol in a clinic setting to terminate a pregnancy up to seven weeks, provided that the doctor has either on-site capability or access to a facility capable of performing surgical abortion in the event of a failed or incomplete medical abortion. However, the Drug Controller of India has approved mifepristone provision only by a gynaecologist, thus effectively restricting access to women in urban areas. National consensus guidelines and protocolsCitation28 for medical abortion are currently being developed.

Current law and policy: what is still missing?

A major criticism of the MTP Act is its strong medical bias. The “physicians only” policy for providers excludes mid-level health providers and practitioners of alternative systems of medicine. The requirement of a second medical opinion for a second trimester abortion further restricts access, especially in rural areas.

The MTP Act mandates the State to provide abortion services at all public hospitals. However, the lack of required approval for public health facilities exempts the public sector from the same regulatory processes that apply to the private sector. The assumption that a health institution by virtue of being in the public sector is accountable to the public, and has well-functioning regulatory processes that do not need explication in law and policy, is not correct. Often, any such regulations tend to be defunct or lack transparency. In the context of poor quality abortion care in the public sector,Citation8, Citation29 the same exacting standards should be applied as in the private sector and subject to the same audit procedures that are expected of the private sector. Ironically, however, the private sector in India also remains vastly unregulated and often lacks the self-discipline necessary to adhere to the quality standards specified in the law.

A major gap in abortion policy in India is the lack of explicit policy on good clinical practice and research. National technical guidelines published in 2001Citation30 do not conform with WHO’s international guidanceCitation31 and fail to ensure good clinical practice even at approved abortion facilities. Consequently, sharp curettage by 39—79% of providers Citation8 and continued use of general anaesthesia in 8—15% of reported abortion facilities are still prevalent.Citation32 India has simply not found a way to ensure the use of improved and safer abortion practices brought about through research and continuously evolving reproductive technology.

Abortion law and policy: potential and actual abuse

In the 1960s, abortion discourse was influenced largely by medical and demographic concerns. The human and reproductive rights agenda took centre stage post-ICPD. The National Population Policy of India 2000Citation33 encourages the promotion of family planning services to prevent unwanted pregnancies, but also recognises the importance of provision of safe abortion services which are affordable, accessible and acceptable for women who need to terminate an unwanted pregnancy. In India, though abortion is legally permissible under a wide range of situations, the doctor has the final say. A woman has to justify that her pregnancy occurred despite her having tried to prevent it or that it had been intended but circumstances changed or made it unwanted later. The reality may be that the pregnancy was unwanted from the start, but to justify abortion within the legal framework, the woman may feel she has to say it was contraceptive failure, creating an environment of falsehood.

Abortion law is always open to differing interpretations and though the present socio-political environment allows a more liberal interpretation in most cases, there is always the theoretical danger of more restrictive interpretations under different socio-political and demographic compulsions, without a single word of the text of the law being altered.Citation34 Even today, although Section 3 of the 1971 Act does not deny abortion care to unmarried or separated women or widows, the use of the phrase “Where any pregnancy occurs as a result of failure of any device or method used by any ”married’ woman or her husband for the purpose of limiting the number of children…” may be misconstrued to deny abortion services to unmarried women or require a married woman’s husband’s consent. Though activists have argued for replacing “married woman” with “all women”, this recommendation has not yet been taken up by the Government, as it would imply tacit recognition and sanction of sexual relations among those who are unmarried or were previously married.

Another area of potential abuse of woman’s reproductive rights is the mandatory reporting of post-abortion contraceptive use required by MTP regulations (Form 2), which the State may use to compel abortion providers to achieve family planning targets. Such monitoring often results in a form of coercion of women seeking abortion, especially in the public sector.Citation17

Barriers in abortion service delivery

Abortion care, as with much of health care in India, remains neglected, especially in the public sector. Poor quality of care and a poor work ethos in the public health sector compounded by ineffectual legislation (or failure to implement it) have resulted in an unregulated growth of private sector services which is often exploitative in nature. Although India’s abortion policy and law are progressive, effective translation into improved access to safe abortion care is often impeded by misguided and unnecessary practices.

The law empowers state governments to regulate abortion services. Though states have adapted these rules and regulations, they differ in their interpretation and implementation. With the intent of ensuring safety and preventing unsafe abortions, some States have added layers of non-essential procedures and created administrative delays in the regulatory process and unnecessary controls. Maharashtra, for example, requires there to be a blood bank within 5 km of any abortion facility, a requirement that is both impractical and unnecessary. Some States — Delhi and Haryana — require the floor area and architectural plans of the hospital and details of provision of car parking to be submitted for registration.Citation35 The overall mindset of these States is to control rather than facilitate abortion services. The discriminatory nature of such overzealous regulation becomes apparent when these requirements are applied only to the private sector and not the public sector.

The time and effort needed to procure certification of an abortion facility also reflects the States’ attitude and approach towards abortion. In spite of the new time frame specified for the certification process, mismanagement, bureaucratic hurdles, lack of response and corruption are commonly encountered.Citation29 A nationwide study in 1999 of 118 abortion facilities revealed certification delays ranging from 1—7 years.Citation36 However, a recent survey of facilities in six States surprisingly indicated something quite different. Of the 285 private providers surveyed, those who were certified (25%) had been able to do so within a month. Among those not certified, a third had tried and given up or were still awaiting certification. The remaining two-thirds had not even tried to apply, reflecting either indifference or a casual attitude towards certification, or a general dislike of record-keeping and reporting of post-abortion complications to the State, rather than cumbersome procedures as their reason for not seeking certification.Citation37 Low awareness and misconceptions about the law (e.g. that doctors need not seek certification if they work in small clinics, or only do an occasional abortion, or provide abortions for married women only) are other factors that result in low certification levels of some facilities.Citation38

At times, it is neither law nor policy but providers themselves who creates barriers to access. Though the law does not require spousal or any third party consent for a termination except in the case of a minor, in reality, abortion providers often insist on such consent based on “common belief of the law”. Reasons often cited for provider insistence on spousal consent include the need to safeguard themselves against social and legal problems arising from abortion complications or death, and the low social status of women and their dependence on their husbands.

Lastly, so-called informal fees charged by providers in the public sector or exorbitant charges in the private sector that exploit women’s vulnerability and low awareness of the law, especially in circumstances where the unwanted pregnancy is not socially acceptable, also add barriers to access.Citation39

Abortion and sex determination: different issues

The Prenatal Diagnostic Techniques (Regulation and Prevention of Misuse) Act (PNDT Act) 1994Citation40 which was later amended by the Pre-Conception and Pre-Natal Sex Selection and Determination (Prohibition and Regulation) Act 2002Citation41 prohibits the misuse of antenatal diagnostic tests for the purpose of sex determination which may lead to the abortion of female fetuses. These Acts also prohibit advertising of such use of these tests; require all facilities using them to be registered and prohibit persons conducting such tests to reveal the sex of the fetus.

Though the purposes of the PNDT laws (prohibiting sex determination) and the MTP Act (ensuring safe abortion) are distinct, they were almost inappropriately linked. Following a Public Interest Litigation suit filed in the Supreme Court by Dr Sabu George and the NGOs CEHAT and MASUM in 2000 against the Government of India for failure to implement the PNDT Act, a policy review meeting discussed modifying the MTP Act to prevent sex-selective abortion following sex determination.Citation42 One suggestion was to allow abortion only up to 12 weeks of pregnancy, to prevent sex-selective abortions following amniocentesis or sonography in the second trimester of pregnancy, which can identify fetal sex. Other suggestions included reporting the identity of any woman seeking abortion as well as the sex of the aborted fetus. However, experts resolved that there was no need to amend the MTP Act, as strict implementation of the PNDT Act was what was required. Reporting the woman’s identity would have been a violation of confidentiality. Restricting legal abortion to 12 weeks of pregnancy would have forced women over 12 weeks to seek illegal abortion services, no matter what their reasons for abortion, with obvious health consequences. Recording the sex of the aborted fetus would not only have been unethical but also would have made abortions carried out for other reasons suspect, and might indirectly have made access to safe abortion services more difficult overall.

Abortion law and policy: the way ahead

Recent law and policy reforms, though not radical, still represent a step forward towards ensuring a woman’s right to safe abortion care. It is only in recent years that several national-level consultative effortsCitation43 Citation44 Citation45 Citation46 involving policymakers, professionals bodies like the Federation of Obstetrics and Gynaecology Societies of India (FOGSI) and the Indian Medical Association (IMA), NGOs (notably Parivar Seva Sanstha, CEHAT, Health Watch and the Family Planning Association of India) and health activists, have championed the improvement of access to safe and legal abortion services in India. Many of their recommendations are in line with the objectives and the strategies outlined in the Action Plan of India’s National Population Policy, 2000. They include:

| • | increasing availability and access to safe abortion services, | ||||

| • | creating more qualified providers (including mid-level providers) and facilities, especially in rural areas | ||||

| • | simplifying the certification process, | ||||

| • | de-linking clinic and provider certification, | ||||

| • | linking policy with technology and research and good clinical practice, | ||||

| • | applying uniform standards for both the private and public sectors, and | ||||

| • | ensuring quality of abortion care. | ||||

For these policies to be implemented effectively, they need to be backed by political will and commitment in terms of adequate resource allocation, training and infrastructure support, accompanied by social inputs based on women’s needs. Advocacy and action at both central and state level are required to put the operational strategies relevant to abortion, as detailed in the National Population Policy, 2000 into effect.

References

- M Berer. Making abortions safe: a matter of good public health policy and practice Bulletin of World Health Organization. 78: 2000; 580–592.

- A Rahman, L Katzive, S Henshaw. A global review of laws on induced abortion, 1985—1997 International Family Planning Perspectives. 24: 1998; 56–64.

- R Chhabra, SC Nuna. Abortion in India: An Overview. 1994; Veerendra Printers: New Delhi.

- Government of India. Report of the Shah Committee to study the question of legalization of abortion. 1966; Ministry of Health and Family Planning: New Delhi.

- S Phadke. Pro-choice or population control: a study of the Medical Termination of Pregnancy Act, Government of India, 1971. 1998. At: www.hsph.harvard.edu/Organizations/healthnet/SAsia/repro/MTPact.html

- Government of India. The Medical Termination of Pregnancy Act [Act No. 34, 1971]. 1971; Ministry of Health and Family Planning: New Delhi.

- Government of India. The Medical Termination of Pregnancy Rules and Regulations. Vide GSR 2543. 1975; Gazette of India: New Delhi.

- S Barge. Situation analysis of medical termination of pregnancy in Gujarat, Maharashtra, Tamil Nadu and Uttar Pradesh. Paper presented at MTP workshop, Ford Foundation, 20 May 1997. S Bandewar, R Ramani, A Asharaf. Health Panorama No.2. 2001; CEHAT: Mumbai, 25–34.

- R Chhabra. Abortion in India: an overview Demography India. 25(1): 1996; 83–92.

- Government of India. Family Welfare Programme in India: Year Book 1994—95. 1996; Ministry of Health and Family Welfare: New Delhi.

- S Henshaw, S Singh, T Haas. The incidence of abortion worldwide International Family Planning Perspectives. 25(Suppl.): 1999; S30–S38.

- Indian Council of Medical Research. Illegal Abortion in Rural Areas: A Task Force Study. 1989; ICMR: New Delhi.

- M Karkal. Abortion laws and the abortion situation in India Issues in Reproductive and Genetic Engineering. 4(3): 1991; 223–230.

- Indian Council of Medical Research. Evaluation of the quality of family welfare services at the primary health centre level: an ICMR task force study. 1991; ICMR: New Delhi.

- ME Khan, S Barge, N Kumar. Availability and Access to Abortion Services in India: Myth and Realities. 2001; Center for Operations Research and Training: Baroda.

- K Iyengar, S Iyengar. Elective abortion as a primary health service in rural India: experience with manual vacuum aspiration Reproductive Health Matters. 10(19): 2002; 54–63.

- B Ganatra, S Hirve, S Walawalkar. Induced abortions in a rural community in Western Maharashtra: prevalence and patterns. Working Paper Series. 1998; Ford Foundation: New Delhi.

- M Gupte, S Bandewar, H Pisal. Abortion needs of women in India: a case study of rural Maharashtra Reproductive Health Matters. 5(9): 1997; 77–86.

- B Ganatra, S Hirve, VN Rao. Sex selective abortions: evidence from a community based study in Western India Asia Pacific Population Journal. 16(2): 2001; 109–124.

- B Ganatra, S Hirve. Induced abortions among adolescent women in rural Maharashtra, India Reproductive Health Matters. 10(19): 2002; 76–85.

- A Malhotra, L Nyblade, S Parasuraman. Realizing Reproductive Choice and Rights: Abortion and Contraception in India. 2003; International Center for Research on Women: Washington DC.

- United Nations. Report of the International Conference on Population and Development, Cairo, 5—13 September 1994. 1995; UN: New York.

- United Nations. Report of the Fourth World Conference on Women, Beijing, 4—15 September 1995. 1996; UN: New York.

- United Nations. Key Actions for the Further Implementation of the Programme of Action of the International Conference on Population and Development. 1999; UN: New York.

- United Nations Further Actions and Initiatives to Implement the Beijing Declaration and Platform for Action. 2000; UN: New YorkA/S-23/10/Rev1 (Suppl.3). At: www.un.org/womenwatch/confer/beijing5/

- Government of India. Medical Termination of Pregnancy (Amendment) Act [No.64 of 2002]. 2002; Ministry of Health and Family Welfare: New Delhi.

- Government of India. Medical Termination of Pregnancy Rules and Regulations. Vide GSR 485(E) and 486(E). 2003; Gazette of India: New Delhi.

- Government of India. Consortium for National Consensus for Medical Abortion in India: Proceedings and Recommendations. March 2003. All India Institute of Medical Sciences, and Ministry of Health and Family Welfare: New Delhi.

- S Bandewar. Quality of Abortion Care: A Reality. From Medical, Legal and Women’s Perspective. 2002; CEHAT: Pune.

- Government of India. Guidelines for medical officers for medical termination of pregnancy up to eight weeks using manual vacuum aspiration technique. 2001; Maternal Health Division, Department of Family Welfare, Ministry of Health and Family Welfare: New Delhi.

- World Health Organization. Safe Abortion: Technical and Policy Guidance for Health Systems. 2003; WHO: Geneva.

- Kalpagam B. PSS experience of early abortion services. Paper presented at National Conference on Making Early Abortion Safe and Accessible. Parivar Seva Sanstha. Agra, 11—13 October 2000.

- Government of India. National Population Policy, 2000. 2000; Department of Family Welfare, Ministry of Health and Family Welfare: New Delhi.

- A Jesani, A Iyer. Women and abortion Economic & Political Weekly. 27: 1993; 2591–2594.

- S Hirve. Abortion Policy in India: Lacunae and Future Challenges. Abortion Assessment Project, India. 2003; CEHAT, Health Watch: Mumbai.

- Sheriar N. Manual vacuum aspiration decentralizing early abortion services. Paper presented at: National Conference on Making Early Abortion Safe and Accessible. Parivar Seva Sanstha. Agra, 11—13 October 2000.

- Duggal R, Barge S. Synthesis of multicentric facility survey: a summary. Abortion Assessment Project India. Presented at Dissemination Meeting, New Delhi, 25—26 November 2003.

- Federation of Obstetrics and Gynaecological Societies of India. Safe abortions save lives: understanding the MTP Act. Mumbai: MTP Committee, Medico-Legal Committee FOGSI; New Delhi: Ipas India, 2002.

- Banerjee A. Rapid assessment of abortion clients: a qualitative case study in selected districts of Orissa. Paper presented at Orissa State-level Workshop on Making Abortion Safe and Accessible. Parivar Seva Sanstha. Bhubhaneshwar, 15—17 October 2001.

- Government of India. The Prenatal Diagnostic Techniques (Regulation and Prevention of misuse) Act, 1994. 1996; Gazette of India: New Delhi.

- Government of India. The Pre-Conception and Pre-Natal Sex Selection/Determination (Prohibition and Regulation) Act, 2002. 2003; Gazette of India: New Delhi.

- Government of India. Minutes of Expert Group Meeting to review MTP Act in the context of PNDT Act. 17 April 2002; Chaired by Jt. Secretary, RCH, Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, New Delhi. No.M.12015/15/98-MCH.

- Parivar Seva Sanstha. Workshop on service delivery system in induced abortion. Parivar Seva Sanstha, New Delhi, 21—22 February 1994.

- Family Planning Association of India. Report of a national consultative meeting for improving access to safe abortion services in India. Mumbai, 30 September—1 October 2002.

- Center for Enquiry into Health and Allied Themes. Access to safe and legal abortion — issues and concerns: state-level consultation, Pune, 7 June 1998. S Bandewar, R Ramani, A Asharaf. Health Panorama No.2. 2001; CEHAT: Mumbai, 49–51.

- Government of India, Parivar Seva Sanstha, Ipas. National Conference on making early abortion safe and accessible. Agra, 11—13 October 2000; New Delhi: Ministry of Health and Family Welfare.

- S Hirve. Abortion: policy and practice Seminar. 532(Dec): 2003; 14–19.