Abstract

This study measured the contribution of abortion-related deaths to overall maternal mortality and calculated the underestimation of maternal mortality using verbal autopsy and clinical record review where available. We reviewed 807 death certificates of women aged 12—50 who died in 2001 in two sites of about 1.5 million inhabitants each in the state of Morelos (primarily rural) and the municipality of Nezahualcóyotl (primarily urban) in the state of Mexico. Deaths were classified as definite, possible or non-maternal deaths. Finally, we identified abortion-related deaths and calculated the underestimation of maternal mortality. Among 326 possible maternal deaths, we encountered five misclassified cases: one spontaneous abortion and four non-abortion maternal deaths. Among 32 registered maternal deaths, we found four misclassified cases that were actually second trimester, abortion-related deaths. There were no officially registered abortion-related deaths in either Morelos or Nezahualcóyotl, making the overall underestimation of abortion mortality 100%. Abortion contributed 13.5% of all maternal deaths. The overall underestimation of maternal mortality was 13.5%, higher in Morelos (21.7%). There were no unregistered maternal deaths in Nezahualcóyotl. Unsafe abortion continues to be an important cause of maternal mortality, though first trimester deaths appear to be decreasing. We identified domestic violence as an important cause of death among pregnant and post-partum women, and two abortion-related suicides, and believe these should be reconsidered as indirect maternal deaths. The misclassification of second trimester abortion deaths as maternal deaths from other causes is an obstacle to preventing them.

Résumé

Cette étude a mesuré la proportion des décès par avortement dans la mortalité maternelle globale et a calculé la sous-estimation de la mortalité maternelle. Nous avons examiné 807 certificats de décès de femmes âgées de 12à50 ans mortes en 2001 dans deux sites d’environ 1,5 million d’habitants chacun dans l’Átat de Morelos (surtout rural) et la municipalité de Nezahualcóyotl (principalement urbaine) dans l’Átat de Mexico. Les décès ont été classés comme formels, possibles et non maternels. Enfin, nous avons identifié les décès par avortement et calculé la sous-estimation de la mortalité maternelle. Sur 326 décès maternels possibles, 5 cas étaient mal classés : un fausse couche et quatre décès maternels non imputablesàl’avortement. Sur les 32 décès maternels enregistrés, quatre cas étaient mal classés, se rapportant en faitàdes avortements du deuxième trimestre. Aucun décès par avortement n’avait été enregistré officiellementàMorelos niàNezahualcóyotl, portantà100% la sous-estimation globale de la mortalité par avortement. Les avortements ont provoqué 13,5% des décès maternels. La sous-estimation de la mortalité maternelle était de 13,5%, supérieureàMorelos (21,7%). Il n’y avait pas de décès maternels non enregistrésàNezahualcóyotl. L’avortement non médicalisé demeure une cause importante de mortalité maternelle, mÁme si les décès pendant le premier trimestre semblent diminuer. Nous avons identifié la violence familiale comme responsable de nombreux décès de femmes enceintes et de jeunes mères, et deux suicides liésàl’avortement, et nous pensons qu’ils devraient Átre reconsidérés comme décès maternels indirects. La classification erronée des décès par avortement au deuxième trimestre comme décès maternels dusàd’autres causes entrave leur prévention.

Resumen

Este estudio midió la contribución de las muertes relacionadas con el aborto a la cifra general de mortalidad materna y calculó la subestimación de la mortalidad materna mediante la autopsia verbal y la revisión de expedientes clinicos, cuando fue posible. Revisamos 807 certificados de defunción de mujeres entre los 12 y 50 años, quienes murieron en el 2001 en dos Estados, de aproximadamente 1.5 millones de habitantes, en el estado de Morelos (principalmente rural) y en el Municipio de Nezahualcóyotl (principalmente urbano) en el estado de México. Las muertes se clasificaron como muertes maternas definitivas, posibles o no maternas. Finalmente, identificamos las muertes atribuibles al aborto y calculamos la subestimación de la mortalidad materna. Entre 326 posibles muertes maternas, encontramos cinco casos mal clasificados: un aborto espontáneo y cuatro muertes maternas no atribuibles al aborto. Entre 32 muertes maternas registradas, encontramos cuatro casos mal clasificados, que fueron muertes en el segundo trimestre relacionadas con aborto. Ni en Morelos ni en Nezahualcóyotl se registraron oficialmente muertes relacionadas con el aborto, lo cual da una subestimación general de un 100% de la mortalidad por aborto. El 13.5% de todas las muertes maternas se atribuyó al aborto. La subestimación general de la mortalidad materna fue de 13.5%, más alta en Morelos (21.7%). En Nezahualcóyotl se registraron todas las muertes maternas. El aborto inseguro continúa siendo una causa importante de mortalidad materna, aunque el número de muertes en el primer trimestre parece estar disminuyendo. Identificamos la violencia intrafamiliar como una causa importante de defunción entre las mujeres embarazadas y en postparto, y dos suicidios relacionados con el aborto, y creemos que éstas deben reconsiderarse como muertes maternas indirectas. La clasificación errónea de las muertes atribuibles al aborto en el segundo trimestre como muertes maternas por otras causas obstaculiza su prevención.

Maternal mortality is a health indicator that clearly reflects socio-economic conditions.Citation1 In Mexico, although economic indicators have improved steadily for almost a decade,Citation2 maternal mortality has not seen a corresponding decrease during the 1990s, and remains higher than in other countries in the region with similar economic indicators.Citation3 In Mexico, maternal mortality is higher in the poorest states and deaths are concentrated among women from poor socio-economic strata.Citation4 More than 80% of maternal deaths are attributed to direct causes, with abortion the fourth leading cause (5—8%).Citation1 Citation2 Citation5 Citation6 Citation7

Abortion is legally restricted and culturally stigmatised in Mexico, and unsafe abortion is prevalent, with estimates ranging from 100,000—1,600,000 unsafe abortions per year.Citation8 Citation9 Citation10 More accurate data on the contribution of unsafe abortion to maternal mortality remains a paramount methodological challenge. Verbal autopsy, i.e. interviewing family members or close friends of a deceased person, can supplement government statistics as a means to obtain more accurate data. Citation11 It aims to reconstruct the biomedical and social circumstances which led to the death by using a guided interview, and has been used effectively in studies of maternal and infant mortality.Citation12 Citation13 Citation14 Citation15 This is the first study we know of using verbal autopsy to identify abortion-related maternal deaths.

Maternal mortality refers to deaths resulting from pregnancy or childbirth, or within 42 days of termination of pregnancy, from any cause related to, or aggravated by, the pregnancy or its management in a given population.Citation16 Although the overall underestimation of maternal mortality has been documented in Mexico, no study has specifically focused on abortion-related deaths.Citation12 Citation17 Citation18 Citation19 For this study, we evaluated only registered deaths, or those with a death certificate. Therefore, any newly identified maternal or abortion-related deaths in this study correspond to errors in classification rather than errors in registration. Misclassification occurs when a maternal death is registered with a non-maternal cause of death or, alternatively, when an abortion death is registered as a death due to an obstetric cause other than abortion. Underestimation of maternal mortality refers to the difference between total maternal deaths (discovered and confirmed by verbal autopsy) and officially registered maternal deaths. Underestimation of abortion mortality is measured similarly.

Our objective was to estimate the contribution of abortion to maternal mortality using verbal autopsy in two regions in Mexico. We aimed to identify abortion-related deaths that were registered as non-maternal deaths, and abortion-related deaths that were registered correctly as maternal deaths but from other causes. In so doing, we measured the underestimation both of abortion-related deaths and overall maternal mortality.

Materials and methods

We collected data from June 2001—May 2002 in the state of Morelos (primarily rural) and in the municipality of Nezahualcóyotl (primarily urban), in the state of Mexico. These sites were selected because, 1) they have similar and high maternal mortality ratios,Footnote* 2) they have similarly sized populations of 1.5 million inhabitants, although highly concentrated in Nezahualcóyotl and more widely dispersed in Morelos and 3) they were conveniently located for fieldwork.

After obtaining permission to access files for the sole purposes of this investigation, death certificates were obtained directly from the local Civil Registry for both sites. These certificates were then double-checked with the Central Department of Epidemiology in Mexico City, who confirmed that they corresponded to all deaths of women of childbearing age (12—50) in 2001 in both sites. The Department of Epidemiology receives death certificate information on a month-by-month basis from all municipalities. In Nezahualcóyotl we included death certificates of women who lived there and died in either Nezahualcóyotl or Mexico City. In Morelos we included death certificates only if women both lived and died in Morelos. This was necessary because some women who died in either Morelos or Nezahuacóyotl had a registered address in a distant state, making it impossible for us to contact the family for a verbal autopsy. This criterion meant that some registered deaths in either Morelos or Nezahualcóyotl were not included in the analysis because an outside residency was listed and that some deaths were not included because the women had died elsewhere.

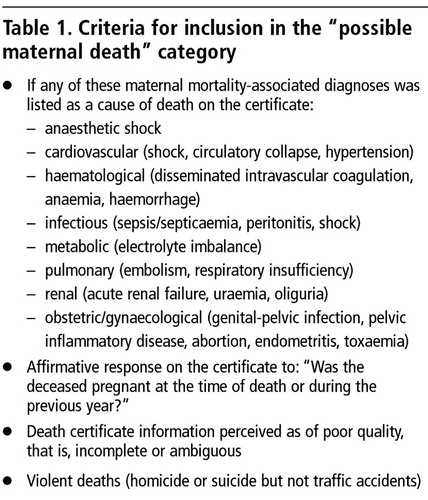

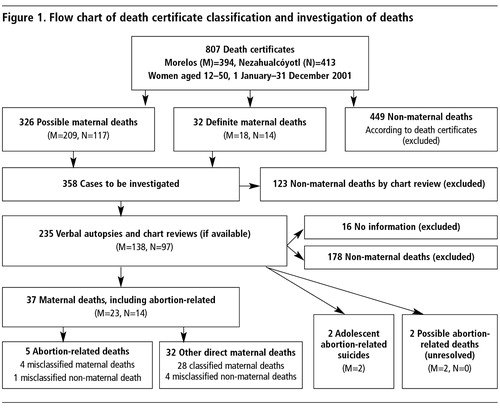

Two physicians classified the death certificates as (Figure 1 ): definite maternal deaths, clearly indicated by cause of death codes on the certificate, or possible maternal deaths, those with at least one of the suspicious diagnoses listed in , or non-maternal deaths (all other certificates). Citation16 Citation17 Citation21 Citation22

Next, we conducted chart reviews and/or verbal autopsy interviews for all definite maternal deaths, to identify abortion deaths misclassified as another type of maternal death, and for possible maternal deaths, to identify maternal and abortion deaths misclassified as non-maternal deaths. For deaths occurring in a hospital or clinic, we began with an evaluation of the medical chart, when available, and in so doing were able to identify cases that were clearly non-maternal (excluded) or clearly maternal and not abortion-related. Verbal autopsy interviews were conducted for all remaining cases of definite maternal deaths and possible maternal deaths (Figure 1).

All interviewers underwent a three-day training in all aspects of verbal autopsy technique. Interviewers were women who had previous training in social sciences and had participated in fieldwork for other studies at the Instituto Nacional de Salud Pública (INSP, National Public Health Institute). The training, conducted by the authors at the INSP, included study objectives, general concepts of the verbal autopsy, mock interviews with constructive critique and pilot interviews in the field.Citation12 For each of the selected cases, the address of the deceased woman was identified from the death certificate. A member of the project staff made a trip to the home to identify possible informants (husbands, mothers, other family members, neighbours or friends), explain the study, obtain informed consent and conduct the interview if the informant was willing. Otherwise, arrangements were made for a convenient date and time to conduct the interview or to locate a more appropriate informant. When the information from one informant was either incomplete or inconsistent, a second, or sometimes third informant was sought. These additional informants were also relatives, friends or neighbours of the deceased. In cases of violent deaths, we were careful to include an informant other than the husband or partner. In cases of suspicious adolescent deaths, we made a special effort to interview a close friend in addition to the relative.

Informed consent was obtained from the interviewee prior to the interview. Other individuals were asked to leave the home so the interview could be conducted in private. The verbal autopsy began with a series of filter questions to assess whether the respondent was well informed about the circumstances surrounding the death. We asked about partners, contraception, the possibility of pregnancy and about specific symptoms shortly prior to death that may have been attributable to abortion (vaginal bleeding, foul-smelling discharge, cramping) or pregnancy (headache, swelling, high blood pressure, seizures). We also asked about ultrasound reports, visits to doctors, recent uterine aspiration or dilatation and curettage (D&C). Finally, we asked the respondent to tell us in their own words how the death occurred. This was done for all cases of possible abortion-related deaths as well as for the definite maternal deaths, in order to clarify the cause of death.

If it was possible that the woman had been pregnant, the verbal autopsy continued with more in-depth questioning, during which we asked about the circumstances of the possible or confirmed pregnancy, and whether it had been desired or planned. In cases of possible first or second trimester abortion, we asked directly whether the interviewee believed an induced abortion might have occurred. We also asked about the physical and emotional state of the deceased, and about sexual partners and violence. The instrument was designed and implemented according to published recommendations for verbal autopsy studies and those addressing the issue of violence.Citation11 Citation22 Citation23 Citation24 Citation25 Citation26

All questionnaires were identified by number with no identifiers in order to maintain confidentiality. Interviewees were offered psychological support arranged through the local public health clinic, when necessary. Interviewers also participated in group therapy sessions throughout the course of the study. This became necessary to ease the emotional burden that came from learning about the content and conditions of the deaths they were investigating.Citation27 The study received ethical approval from the INSP Committee on Human Research and the Population Council Institutional Review Board.

Using primarily verbal autopsy information, we reviewed each case and classified it as a maternal death or non-maternal death. Maternal deaths were further sub-classified as abortion deaths or other maternal deaths (Figure 1). We compared our numbers to selected official figures reported by the Ministry of HealthCitation28 corresponding to our study sites. Government statisticians coded the causes of deaths according to the International Classification of Diseases, 10th Review (ICD-10).Citation16 For each case, we double-checked multiple variables to confirm which deaths we categorised as maternal and abortion-related maternal deaths that had not been reported by the Department of Epidemiology (DGE).

Results

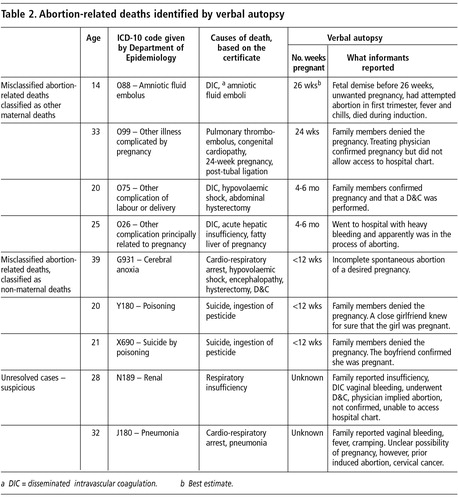

We reviewed a total of 807 death certificates (Morelos (M)=394, Nezahualcóyotl (N)=413) (Figure 1). These certificates were classified as 32 definite maternal deaths (M=18, N=14), 326 possible maternal deaths (M=209, N=117), and 449 non-maternal deaths. Thus, we had 358 definite and possible maternal deaths to investigate, of which we excluded 123 cases by chart review alone as not being abortion-related. Using verbal autopsy alone or with chart review, we classified the remaining 235 cases. For the majority of the cases (94%) only one verbal autopsy was necessary. For the remaining cases we conducted two (5% of cases) or three verbal autopies (1% of cases). Sixteen cases were excluded for failure to obtain reliable information (no adequate informant was identified). We identified 37 confirmed maternal deaths (5 abortion deaths and 32 other direct maternal deaths) 2 abortion-related suicides and 2 cases that remained unresolved.

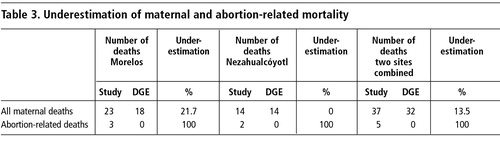

Among all possible maternal deaths (326) we identified five maternal deaths that were not registered as such. All five of these deaths occurred in Morelos, where we confirmed a total of 23 maternal deaths (five more than the official figure of 18), resulting in an overall maternal death underestimation of 21.7%. These five deaths consisted of one spontaneous abortion-related death and four other direct maternal deaths. There were two additional cases of abortion-related suicides and two unresolved cases (abortion possible) that we excluded from the calculation of underestimation ( ). Although we are confident that the two suicides occurred in connection with an unplanned pregnancy, they are not by definition considered direct maternal deaths, and therefore could not be included in the calculation of underestimation. There were no misclassified maternal deaths in Nezahualcóyotl and therefore no underestimation of maternal mortality there. If we combine data for both sites, with a total of 37 maternal deaths, the underestimationFootnote* is 13.5% ( ).

Through verbal autopsy, we identified four abortion-related deaths (2 in each site) that were misclassified as deaths due to obstetric causes. Combining abortion deaths from the two categories above, we arrived at a total of five abortion deaths. Since the DGE reported no abortion deaths in either site, the underestimation is 100% ().

Misclassified abortion-related deaths

In Morelos, the first case was a 14-year-old girl with a late second trimester intrauterine fetal death. The family was unable to report a clear cause of death. The deceased’s mother knew of the pregnancy, and reported that her daughter had tried to abort during the first trimester. She could not confirm another attempt to abort later in the pregnancy. The mother reported that her daughter had had fever and chills and died during an induction of labour. The death certificate reports amniotic fluid emboli and the DGE assigned the corresponding ICD-10 code O88. Therefore, this death was officially classified as an obstetric death due to an amniotic fluid emboli.

The second case was a 33-year-old woman with a known congenital heart problem. Family members denied the pregnancy. The treating physician confirmed a 24-week pregnancy that “was lost” and death caused by complications occurring during tubal ligation. The death certificate reports a 24-week pregnancy and tubal ligation. The ICD-10 code was O99 corresponding to “other illness complicated by pregnancy”. We were not allowed to review the medical record. Because we were able to confirm with the family that the woman had a serious congenital heart defect that could be complicated by pregnancy and the physician confirmed she had been pregnant at the time of death, we suspect that she may have died from cardiac complications occurring during an attempted late abortion. The physician was uncooperative, and we were unable to confirm this, however.

In Nezahualcóyotl, the first case was a 39-year-old woman, for whom the certificate lists hypovolaemic shock and disseminated intravascular coagulation as causes of death and the ICD-10 code O75, “other complications of labour and delivery, not otherwise specified”. Family members confirmed a 4—6 month pregnancy, and that the patient underwent a D&C (or a dilatation and evacuation procedure) in the hospital shortly before her death, which occurred in hospital. Again, there was no documentation of an unsafe abortion procedure, and we were unable to locate the medical record or a physician who was involved in the case.

The last misclassified abortion death occurred in a 25-year-old woman, for whom the death certificate reported disseminated intravascular coagulation, acute hepatic insufficiency and fatty liver of pregnancy. The ICD-10 code given was O26, “other complications principally related to the pregnancy”. The woman had a confirmed five-month pregnancy and family members reported that she bled heavily and underwent a dilatation and evacuation procedure in the hospital prior to her death.

There was one abortion-related death reported as a death from non-maternal causes. This woman had a spontaneous abortion of a desired pregnancy. She was initially sent away from the hospital when she first presented with vaginal bleeding. She returned later with continued heavy bleeding and underwent a D&C, then a hysterectomy, and according to her family, died from blood loss. The death certificate reports hysterectomy and D&C, but the ICD-10 code given was G931— cerebral anoxia.

There were also two suicides that occurred in adolescents that we listed as abortion-related because of their social context. In both cases, the girls lived with their parents. Interviewed family members, including the mothers, had no knowledge of or denied the pregnancies, reported no previous episodes of depression or mental instability, and could not identify any reason for the suicide. But informants outside the families (a close friend or boyfriend) confirmed the pregnancies and the desperation these young women felt. These deaths both occurred during the first trimester by ingesting pesticides. No informant, however, could tell us whether these adolescents had made comments about aborting or dying. We listed these deaths as abortion-suicides, but to be consistent with ICD-10 we excluded them from the final tally of maternal deaths. Both death certificates reported suicide by ingestion of pesticides.

We also found evidence that pregnancy-related domestic violence was an important but neglected component of maternal deaths. In Morelos, four deaths were from the consequences of domestic violence during pregnancy or the puerperium. We found that this reproductive event was the direct trigger for the homicide and suicides. Because of that, we recommend that violent deaths related to pregnancy should be consider as indirect obstetric deaths.Citation30

Unresolved cases: possible abortion-related deaths

There were two cases in Morelos that we labelled as possible abortion-related deaths because after verbal autopsy and/or chart review there remained doubt as to whether or not the women had been pregnant at the time of death. The causes of death were suspicious and occurred in one woman with cervical cancer and another with renal insufficiency. For both cases, there was significant doubt in at least one informant that the woman may have been pregnant and/or tried to abort at or near the time of death. Therefore, we classified these cases as possible abortion-related deaths. For all other maternal deaths, there was at least one informant who was absolutely certain that the woman had definitely been pregnant.

Discussion

This study highlights the need to interpret death certificate data related to maternal deaths with caution. The ICD-10 coding, in cases of abortion, neither corresponded with the diagnoses listed on the certificate nor with the verbal autopsy. For other cases of maternal deaths, this discrepancy was not specifically reported or evaluated, although we did find cases of misclassification of other causes of maternal death as well.

For our combined sites, the overall underestimate of maternal mortality was 13.5% (5/37) although this was higher in Morelos (21.7%, 5/23) and there were no additional maternal deaths identified in Nezahualcóyotl. Other Mexican verbal autopsy studies have reported underestimates of 8% in Querétaro (1995), 22% in San Luis Potosá (1995), and 27% in Guerrero (1995).Citation12 An older study from Mexico City in 1989 reported a 39.7% underestimate and one in Morelos in 1990 reported a 37.5% underestimate.Citation18, Citation29 Based on the latter figure, the underestimation of maternal mortality in Morelos has decreased. The fact that we encountered no new maternal deaths in Nezahualcóyotl is significant and discussed below.

Although the underestimation of maternal mortality seems to be decreasing, the same may not be true for abortion mortality. In our study, we found that abortion-related deaths were underestimated (in fact, there were no officially listed abortion-related deaths) primarily because of misclassification rather than under-reporting. However, this underestimation of abortion deaths only minimally affected the estimate of overall maternal mortality because all but one of the abortion deaths was already classified as maternal, with another cause. The contribution of abortion to overall maternal mortality was underestimated accordingly.

Officially, each year, unsafe abortion contributes 5—8% of maternal deaths in Mexico. In our study, we estimate that abortion complications accounted for 13.5% of maternal deaths when officially, there were no abortion deaths listed at either site.Citation5 Citation6 Citation7 If we were to add the abortion-related suicides, the contribution of abortion to overall maternal mortality would increase to 18.9% combining both study sites, and 21.7% for Morelos alone. In reviewing the second trimester deaths, it is apparent that haemorrhage, hysterectomy and disseminated intravascular coagulation (a condition in which clotting factors and platelets are consumed, often due to infection, hypoxia or uncontrolled haemorrhage) were common themes. Each of these second trimester deaths occurred in a hospital or private clinic, and in each case an obstetric or gynaecological intervention was attempted. They did not occur at home or without benefit of medical treatment. Clearly, these deaths highlight the need for further training, greater resources and improved awareness of complications of second trimester terminations.

We investigated fewer deaths in Nezahualcóyotl than in Morelos. The death certificate information in Morelos was, in general, of poor quality or absent, and primarily for this reason, we classified 28% more certificates as possible maternal deaths in Morelos than in Nezahualcóyotl. Factors contributing to the differences in maternal deaths and misclassification in the two sites deserve further investigation. Although the study was not designed with this in mind, and contrary to what we expected, more selected deaths occurred in the home in Nezahualcóyotl (60%) compared to Morelos (40%) and a similar number of selected certificates were completed by the treating physician in each location (Nezahualcóyotl 24%, Morelos 27%). This does not explain why fewer certificates were selected in Nezahualcóyotl. It may simply be greater training and supervision for those completing the certificates in the more urban Nezahualcóyotl.

Another important factor responsible for misclassifying the abortion-related deaths in both sites was that on most of the certificates the length of pregnancy was not indicated. As a result, abortion-related maternal deaths were incorrectly classified as third trimester maternal deaths rather than as second trimester abortion-related deaths.

Women in Morelos tend to have less access to care or get lower quality of care than those in Nezahualcóyotl, just on the border of Mexico City. For instance, more rural government clinics are staffed by less experienced physicians than urban clinics. In Morelos, in general, there is less confidence in public medical services and more reliance on traditional birth attendants or other unskilled care in cases of gynaecological emergency or acute complications. Additionally, the women who died in Morelos were less educated and poorer than those in Nezahualcóyotl. A case—control study of maternal deaths conducted in three other states of Mexico identified educational attainment as the only protective factor.Citation12

The limitations of our study are related to the difficulties of investigating abortion, a very sensitive topic, as well as some operational challenges. Although verbal autopsy allowed us to identify several pieces of conclusive information about abortion procedures and adjust the maternal mortality figures, none of our informants was able to confirm, with total certainty, that an induced abortion had occurred. Abortion is particular in the sense that a misclassification is probably less due to an error of diagnosis and more due to a desire to hide the true cause of death. This is not surprising given the legal status of abortion in Mexico.

In general, we found that women relatives and friends were more valuable informants than men. However, although we consistently attempted to speak first with a female relative, as other verbal autopsy studies suggest, this approach was not always the most effective, and these relatives were sometimes not the most reliable informants.Citation12 Furthermore, for abortion-related deaths, and especially for suicides and other violent cases, family members were often neither the most reliable nor the most consistent informants. Specifically, in the case of adolescent suicide, the mother was not the best informant and it was important to reconsider who might be the most reliable informant.

Regretfully, because of the strict ICD-10 definition of maternal death, it is impossible to assess the extent to which abortion-related suicides contribute to abortion deaths, particularly among adolescents, as they tend to be classified only as suicides. In addition to these suicides, we identified domestic violence as an important cause of death among pregnant and post-partum women, and believe that these should both be reconsidered as indirect causes of maternal death.

Another operational difficulty we experienced was in accessing some medical records, particularly from private clinics. Although in general, medical charts were available and provided valuable supplemental information, this was not always the case. This was both because some records could not be located and because we were not allowed to see some records. This is important in countries like Mexico, where private practice is unregulated and where quality of care is often poor. Another limitation was due to study design. Due to limited resources we could only contact family members or neighbours who lived in the study sites. This meant we were not able to consider deaths that had occurred in the study sites of women who had lived in other locations (although there were few such deaths in either site). However, because published government statistics on maternal mortality include all deaths occurring in a given location, regardless of residence, we had to compare our findings to selected official figures when calculating the underestimation.

Finally, despite using an exhaustive list of death certificate diagnoses to select cases, we might have missed cases that were classified as a totally unrelated cause. To overcome this, the only solution would have been, albeit extremely expensive and logistically impossible, to conduct verbal autopsies for all deaths of reproductive age women as suggested by the RAMOS (Reproductive Age Mortality Survey) methodology.Citation31 However, it is unlikely this would have made a significant difference in the overall underestimation for two reasons. First, our study used wider inclusion criteria and found a smaller underestimation of maternal mortality than previous studies.Citation12, Citation18, Citation29 Second, we found no underestimation of maternal mortality in Nezahualcóyotl, which indicates improvements in the quality of death certificate classification and coding.

Overall, it is significant that we found suspicious second trimester abortion deaths and no definitive case of death due to unsafe first trimester induced abortion. Although this might have resulted from limitations in verbal autopsy techniques, it may also reflect a shift in the safety of first trimester pregnancy termination methods. There has been some discussion recently regarding the impact of misoprostol on maternal morbidity and mortality in Latin America. A study of women treated for post-abortion complications in Brazil found fewer post-abortion complications in women who said they had induced the abortion with misoprostol.Citation32 Focus groups with gynaecologists in Brazil confirm doctors’ perception that use of the drug was reducing abortion complications.Citation33 Misoprostol is available and used for abortion in Mexico but so far there are no published reports regarding its prevalence.Citation34 It is also possible that contemporary Mexican abortion providers are more trained than those in the past and are using safer, first trimester surgical abortion techniques as well, thereby decreasing the number of abortion-related deaths. Another reason might be the impact of almost 20 years of post-abortion care programmes in Mexico, whose aim has been precisely to treat unsafe abortion complications to decrease deaths.Citation35

Promoting objective and ongoing public debate about abortion and its consequences may lower social prejudice. However, health workers in charge of treating, reporting and coding the causes of deaths must correctly classify abortion deaths as such. The reluctance of hospital personnel to provide access to charts and the reluctance of physicians to discuss these cases, especially of second trimester abortion-related deaths, underscores their discomfort in acknowledging and therefore classifying these deaths accurately.

Health workers need to be better trained in dilatation and evacuation procedures and management of second trimester abortion, particularly in rural settings. A campaign should be considered to sensitise physicians and registry officials in how to correctly complete death certificates, paying more careful attention to number of weeks of pregnancy when classifying maternal deaths. Until abortion deaths are fully acknowledged, further reduction in maternal mortality is made more difficult because the authorities will not have accurate data on which to base the allocation of resources and training appropriately.

Acknowledgements

This study was a joint collaboration between the Mexican Instituto Nacional de Salud Pública, Ministry of Health Department of Epidemiology (DGE) and the Population Council Regional Office for Latin America and the Caribbean. This study was supported by the David and Lucile Packard Foundation grant No. 2000-11203 to the Population Council. We would like to thank the health authorities from the states of Mexico, Morelos and Mexico City. In particular, from the state of Mexico: Gregorio Escamilla, Chief of Sanitation in Nezahualcóyotl; Agustán Mendoza Becerril, Sub-Director of Forensic Services, Nezahualcóyotl; and Fernando Jiménez, Director of Epidemiology. From Mexico City: Jorge Lara, Department of Statistics, Ministry of Health; José Ramón Fernandez, Director of Forensic Services, Ministry of Health; Juan Manuel Castro, Director of Health Services, Ministry of Health; and Carlos lvarez Lucas, General Director of Epidemiology, Ministry of Health. We thank also the authorities from the Instituto Mexicano del Seguro Social for the states of Mexico and Morelos and would like to acknowledge the support of Minerva Romero and Isela Aquino.

Notes

* In 1998, the maternal mortality ratio in the state of Mexico was 75 to 100,000 live births and in Morelos 79 to 100,000.Citation20

* Underestimation = (number of confirmed deaths) minus (number of reported deaths) 100, divided by (number of confirmed deaths).

References

- WHO /UNFPA/UNICEF/World Bank Statement. Reduction of maternal mortality. 1999; WHO: Geneva.

- World Bank Group. World Development Indicators. Data Query for 2001. At: http://devdata.worldbank.org/data-query. Accessed 1 October 2003

- World Health Organization. Revised 1990 Estimates of Maternal Mortality: A New Approach by WHO and UNICEF. 1996; WHO: Geneva.

- R Lozano, B Hernández, A Langer. Factores sociales y económicos de la mortalidad materna en México. MC Elu, A Langer. Maternidad sin Riesgos en México. 1994; IMES: México DF, 43–52.

- Secretaráa de Salud, Dirección General de Salud Reproductiva. Mortalidad Materna de los Estados Unidos Mexicanos 1980—1999. 2001; INEGI/SSA: México DF.

- M Lezana. Evolución de las tasas de mortalidad materna en México. M Elu, E Pruneda. Una nueva mirada a la mortalidad materna en México. 1999; Comité Promotor por una Maternidad sin Riesgo en México: Mexico DF, 53–70.

- Estadásticas de mortalidad relacionada con la salud reproductiva, México, 2002. Salud Pública de México 2004;46(1):75—88.

- J Paxman, A Rizo, L Brown. The clandestine epidemic: the practice of unsafe abortion in Latin America Studies in Family Planning. 24(4): 1993; 205–226.

- Alan Guttmacher Institute. Aborto Clandestino: Una Realidad Latinoamericana. 1994; Alan Guttmacher Institute: New York.

- Consejo Nacional de Población. Ejecución del Programa de Acción de la Conferencia Internacional sobre la Población y el Desarrollo. 1999; CONAPO: México.

- C Ronsmans, O Campbell. Verbal Autopsies for Maternal Deaths. 1994; School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine: London.

- A Langer, B Hernández, C Garcáa. Identifying interventions to prevent maternal mortality in México: a verbal autopsy study. M Berer, TKS Ravindran. Safe Motherhood Initiatives: Critical Issues. 2000; Reproductive Health Matters: London, 127–136.

- N Ioan, A Langer, B Hernández. The aetiology of maternal mortality in developing countries: what do verbal autopsies tell us? Bulletin of World Health Organization. 79(9): 2001; 805–810.

- World Health Organization. Beyond the Numbers: Reviewing Maternal Deaths and Complications to Make Pregnancy Safer. 2004; WHO: Geneva.

- SP Shrivastava, K Anjani, K Arvind. Verbal autopsy determined causes of neonatal deaths Indian Pediatrics. 38: 2001; 1022–1025.

- World Health Organization. International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems. 10th review. 1993; WHO: Geneva.

- R Puffer, G Griffith. Caracterásticas de la mortalidad urbana. 1967; PAHO: Washington DC.

- B Hernández, A Langer, M Romero. Factores asociados a la muerte materna hospitalaria en el Estado de Morelos, México Salud Pública México. 36(5): 1994; 521–528.

- S Reyes. Mortalidad Materna en México. 1994; Instituto Mexicano del Seguro Social: México DF.

- Subsecretaráa de Planeación, Dirección General de Estadástica e Informática de la Secretaráa de Salud. Mortalidad Materna 1998. 1998; Secretaráa de Salud: México, DF.

- L Muñoz, H Ññez, E Becerra. Mortalidad materna en el Instituto Materno-Infantil de Bogotá (1976—1980) Revista de la Facultad de Medicina. 39(4): 1985; 331–351.

- K LaGuardia, M Rothoz, P Belfort. A 10-year review of maternal mortality in a municipal hospital in Rio de Janeiro: a cause for concern Obstetrics and Gynecology. 75(1): 1990; 27–32.

- R Gray, G Smith, P Barss. The use of verbal autopsy methods to determine selected causes of death in children. 1990; Johns Hopkins University School of Hygiene and Public Health: Baltimore.

- C Ronsmans, A Vanneste, J Chakraborty. A comparison of three verbal autopsy methods to ascertain levels and causes of maternal deaths in Matlab, Bangladesh International Journal of Epidemiology. 27(4): 1998; 660–666.

- World Health Organization. Putting Women’s Safety First: Ethical and Safety Recommendations for Research on Domestic Violence against Women. 2001; WHO: Geneva.

- World Health Organization. Verbal Autopsy for Maternal Deaths. 1995; WHO: Geneva.

- H Espinoza, B Hernández, L Campero. Muertes maternas por aborto y por violencia en México: narración de una experiencia en la formulación e implementación de una metodologáa de investigación Perinatologáa y Reproducción Humana. 17(4): 2003; 193–204.

- Secretaria de Salud, Dirección General de Epidemiologáa, Reporte de Muertes Maternas, Documento interno, 2003.

- A Langer, B Hernandez, M Romero. Study of underestimation of maternal mortality in Morelos. Final Report INSP. 1993.

- Espinoza H, Camacho V. Maternal death due to domestic violence. Revista Panamericana de Salud Pública/Pan American Journal of Public Health. (Forthcoming 2005)

- University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. MEASURE-Evaluation. Reproductive Age Mortality Survey (RAMOS). 2003; University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill: Chapel HillAt: www.cpc.unc.edu/measure/publications/tools/cmnht/t20_abstract.html. Accessed 15 October 2003.

- S Costa, M Vessey. Misoprostol and illegal abortion in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil Lancet. 341(8855): 1993; 1258–1261.

- R Barbosa, M Arilha. The Brazilian experience with Cytotec Studies in Family Planning. 24(4): 1993; 236–240.

- H Espinoza, K Abuabara, C Ellertson. Physicians’ knowledge and opinions about medication abortion in four Latin American and Caribbean region countries Contraception. 70(2): 2004; 127–133.

- FC Greenslade, WH Jansen. Post-abortion care services: an update from PRIME. Resources for Women’s Health. Ipas/PRIME. 1998