Abstract

Menstrual regulation (MR) using vacuum aspiration is widely available in Bangladesh through public, NGO and private sector facilities, even though abortion is illegal except to save a woman’s life. For more than two decades the MR programme was run as a vertical programme. In 1998 the Government of Bangladesh introduced the Health and Population Sector Programme (HPSP) incorporating menstrual regulation into the essential services package. This paper reports a situation analysis of the MR Programme under the HPSP, using the World Health Organization rapid evaluation methodology. In spite of wide availability, barriers such as distance to health facilities and transportation costs, unofficial fees, lack of privacy, confidentiality and cleanliness in public health facilities, and in some cases attitudes of service providers, are limiting access to MR services. Quality of care is compromised by inadequacies in infection control and in provider training and counselling. Health system weaknesses include gross under-reporting of cases by providers who do not wish to share unofficial fees, which affects monitoring and adequate provision of supplies. The HPSP has caused uncertainty regarding supervision in public sector facilities, and adversely affected training by NGOs and government—NGO coordination. Services in part of the NGO sector have also been affected by funding changes. To make the programme as a whole more effective, all these issues have to be addressed.

Résumé

La régulation menstruelle par aspiration est largement disponible au Bangladesh dans des centres publics, privés et gérés par des ONG, mÁme si l’avortement n’est autorisé que pour sauver la vie de la femme. Pendant deux décennies, le programme de régulation menstruelle a été administré verticalement. En 1998, le Gouvernement a introduit le Programme du secteur de la population et de la santé (HPSP) incluant la régulation menstruelle dans les services essentiels. Cet article décrit une analyse du programme de régulation menstruelle, avec la méthodologie d’évaluation rapide de l’OMS. La distance avec les centres de santé et le co t des transports, les paiements officieux, le manque de confidentialité et d’hygiène dans les centres publics et parfois l’attitude des prestataires limitent l’accèsàces services, pourtant très nombreux. La qualité des soins est compromise par l’inadéquation des mesures contre les infections, de la formation des praticiens et de l’orientation. La sous-notification flagrante des cas, imputable aux prestataires ne souhaitant pas partager les honoraires officieux, entrave le suivi et la distribution des fournitures. Le HPSP a provoqué l’incertitude quantàla supervision des centres du secteur public et contrarié la formation assurée par les ONG et la coordination Gouvernement-ONG. Certains services des ONG ont aussi été lésés par des changements financiers. Pour rendre le programme plus efficace, il faut lever tous ces obstacles.

Resumen

La regulación menstrual (RM) por medio de la aspiración endouterina se practica ampliamente en Bangladesh en establecimientos de las ONG y de los sectores público y privado, a pesar de que el aborto es ilegal excepto para salvar la vida de la mujer. En 1998, el gobierno de Bangladesh inició el Programa del Sector Salud y Población (HPSP), mediante el cual se incorporó la regulación menstrual en los servicios esenciales. En este artáculo se informan los resultados de un análisis situacional del Programa de RM bajo el HPSP, utilizando la metodologáa de evaluación rápida de la OMS. Pese a la amplia disponibilidad de los servicios de RM, su acceso se limita por barreras tales como la distancia a los establecimientos de salud y los costos de transporte, las tarifas extraoficiales, la falta de privacidad, confidencialidad y limpieza en los establecimientos de salud públicos y, en algunos casos, las actitudes de los prestadores de servicios de salud. La calidad de la atención está comprometida por las deficiencias en el control de infecciones, la capacitación de los proveedores y la consejeráa. Entre las debilidades del sistema de salud figuran un alto subreportaje de los casos por parte de los proveedores quienes no desean compartir las cuotas extraoficiales. El HPSP ha causado duda respecto a la supervisión en los establecimientos de salud del sector público y ha afectado adversamente la capacitación coordinada por las ONG y el gobierno-ONG. Para lograr que el programa en general sea más eficaz, es necesario abordar y solucionar todos los aspectos mencionados.

Bangladesh is unique in South Asia in making menstrual regulation (MR) services available to women at the community level. Menstrual regulation involves evacuation of the uterus by vacuum aspiration within 6—10 weeks of a missed menstrual period. Although abortion is prohibited in Bangladesh except to save a woman’s life (derived from the Penal Code of India 1860 and the British Offences against the Person Act 1861), menstrual regulation is not prohibited as it is considered to be an “interim method to establish a state of non-pregnancy in a woman who is at risk of being pregnant”. Hence, it is usually done without a pregnancy test.Citation1

According to the Bangladesh Demographic and Health Survey of 1999—2000, 5% of currently married women had had an MR procedure.Citation2 An estimate published in 1997 found that close to 500,000 MR procedures are performed annually in Bangladesh.Citation3

The Government of Bangladesh (GOB) introduced MR services on a limited scale in 1974 in a few isolated urban government family planning clinics. In 1978, the Pathfinder Fund began a training and service programme for MR in seven medical colleges and two government district hospitals. This was the start of what was to become the Menstrual Regulation Training and Services Programme (MRTSP). In 1979, the government included MR in the national family planning programme and instructed doctors and paramedics to provide MR services in all government hospitals and in health and family planning complexes.

Currently MR is widely practised throughout the country and is available at all tiers, from district and higher level hospitals down to union (consisting of 15—20 villages) health centres. It is also available in a limited number of NGO clinics and in the private sector. Both doctors and paramedics provide MR, but at the union level female paramedics are the only providers.

Several donors, USAID, Ford Foundation, Population Crisis Committee (now PAI) and Swedish International Development Authority (SIDA), have supported the MR programme. SIDA was the principal donor from 1989 to 1999. The programme was managed jointly by the government and the Coordination Committee of MR Associations in Bangladesh (CCMRA, B). Three NGOs, Bangladesh Women’s Health Coalition (BWHC), Menstrual Regulation Training and Services Programme (MRTSP) and Bangladesh Association for the Prevention of Septic Abortion (BAPSA) have provided MR services and training and have worked together with the government and donors to maintain good standards of care within their own organisations, and the coordination of training and logistical support for the national programme. There is also a National Technical Committee for MR which sets standards and takes policy decisions on technical issues related to MR.

In recent years, the health sector has undergone significant reform. In July 1998, the government of Bangladesh began implementing its fifth five-year, sector-wide programme known as the Health and Population Sector Programme (HPSP), using a sector-wide management approach to improve performance and the efficiency with which health resources are used. As part of these changes, vertical programmes such as MR were incorporated into a unified system, to be funded through a single government/donor funding pool.Citation4

It was therefore important to document how MR services were being provided under the HPSP, the infrastructure available, the quality of service delivery and the implications of unification for MR service delivery. A situation analysis was undertaken to assist the Government to improve accessibility and quality of menstrual regulation services in the next phase of the Health Programme and to develop adequate and appropriate strategies for resourcing the MR programme.

The analysis addressed the current status of the MR services and training programme in Bangladesh in terms of availability, accessibility and quality of care across public, NGO and private sectors. It also identified the strengths and weaknesses of the existing support mechanisms for the programme under the HPSP.

Methodology

The assessment used the rapid evaluation methodology developed as part of the WHO strategic approach to improving reproductive health policies and programmes.Citation5 A key aspect of this methodology is its participatory nature and the active involvement and participation of all stakeholders. The assessment involved a preparatory phase, field observation and data collection, data analysis and preparation of the report. In the preparatory phase, the Government, donors and NGOs were involved. A co-ordinating organisation, the Bangladesh Women’s Health Coalition (BWHC), was selected, an advisory committee was formed, a background paper was prepared and a multidisciplinary assessment team was formed.

A planning workshop was held in Dhaka on 8 September 2002, which brought together about 50 participants representing a broad range of stakeholders, including the Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, Directorates of Health and Family Planning and Women’s Affairs, donor agencies, NGOs providing MR services, medical professional groups, national and international research organisations, women’s groups and parliamentarians. Participants reviewed the background paper, determined gaps and key issues to be addressed in the situation analysis and identified the strategic questions that became the basis of the situation analysis.

The assessment team was comprised of 11 members, six physicians with a public heath background and five social scientists. The assessment team was recruited by BWHC and a consultant with considerable programmatic experience was selected as the co-ordinator and team leader. A senior staff member of the Reproductive Health Alliance in London facilitated the process.

Fieldwork was conducted from 5 October to 4 December 2002 in five districts and at the central level. The qualitative nature of the assessment relied on a purposive, non-probability sample. Selection of field sites was made to ensure broad coverage to reflect major regional, cultural and programmatic differences.

Bangladesh has six geographical divisions which can be divided into three groups on the basis of contraceptive prevalence rate, infant mortality rate and under-five mortality: high-performing divisions (Khulna and Rajshahi), medium-performing divisions (Barisal and Dhaka) and low-performing divisions (Chittagong and Sylhet).Citation2

One district each was selected from Rajshahi, Dhaka and Chittagong divisions on the basis of communication, accessibility of different levels of health facilities, such as upazilla (sub-district administrative units, of which there are about 480 in Bangladesh), health and family welfare complexes, union health and family welfare centres, and community clinics, and an NGO. In each district five upazillas were selected and in each upazilla one union was selected. NGOs providing MR services in the selected upazillas and selected private providers were also covered.

Approaches used to collect information were interviews with key informants, group discussions and observation of health care at the facilities. At the central level, interviews were conducted with senior health policymakers, programme managers, senior NGO personnel and representatives of the Obstetrics and Gynaecology Society, donors and international agencies. At the local level (district, upazilla, union) interviews were conducted with programme managers and service providers, service statistics were reviewed and, where possible, observation of service delivery was carried out. Interviews with programme managers and providers assessed their knowledge, attitudes and skills, elicited their perceptions of MR training, programme management and logistics, and their suggestions on how to improve quality of MR services. Observations focused on a broad range of issues related to quality of care. Interviews were also conducted with private providers including quacks, homeopaths, kabiraj (traditional healers using herbal medication) and providers at private clinics. These interviews focused mainly on the procedures, instruments and medicines used for MR or abortion, complications experienced, success of the procedures and costs.

In-depth interviews and group discussions were conducted with women and men who were present at the facility on that day. These included women who came for MR or for other services, and those accompanying them. Interviews and group discussions focused on respondents’ knowledge, attitudes and perceptions of MR, ways to improve awareness of MR, experience with and attitude towards both public and private service providers, women’s status and decision-making and male involvement. Verbal informed consent was obtained from all respondents prior to interview.

The team visited 44 sites, including 29 GOB, 10 NGO and 5 private service facilities. In total 131 interviews, 35 group discussions and 36 facility observations were conducted. Interviews were held with senior government and NGO personnel, donor representatives and professional experts (20), programme managers (36), service providers (39), women having MR (7), women coming for other services (13), men either accompanying their wives or in the community (12), trainers (2) and trainees (2). Twenty-nine group discussions were held with women and six group discussions with men at health facilities and in the community.

Initially, all data were compiled and organised by facility and community. Data from the policy level and NGO sector were compiled separately. Senior team members undertook a consensus-building exercise to prioritise field observations, with technical assistance from the Reproductive Health Alliance. The findings were grouped into categories that formed the chapters of the report.Citation6 This paper focuses mainly on MR services provided by NGOs and the government sector.

Availability of menstrual regulation services

Public health facilities providing MR services include: district hospitals, maternal and child welfare centres, upazilla health complexes, and health and family welfare centres. In addition, some government training centres/model clinics, such as the Mohammadpur Fertility Services and Training Centre also offer MR services. At present there are 6,500 family welfare visitors and 8,000 doctors trained in MR who are posted in government health facilities. At and below the upazilla level, family welfare visitors are the main providers of family planning and maternal and child health services and MR. Family welfare visitors have at least ten years of formal schooling and receive 18 months of training in family planning and maternal and child health care. They get MR training after their formal posting in a health facility. Currently, female sub-assistant community medical officers are also being trained to provide MR services. Doctors provide emergency back-up. Community clinics do not provide MR services but refer women to them.Citation7

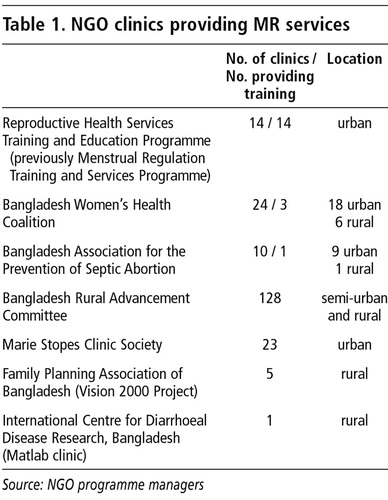

Only a limited number of NGOs provide MR services in their own facilities ( ). The Reproductive Health Services Training and Education Programme provides MR services within government medical colleges and district hospitals. MR services in NGO clinics are usually provided by family welfare visitors from the public sector, nurses, female medical assistants, midwives or specially trained health auxiliaries. All these paramedics receive basic and refresher training in MR. However in a few cases, both physicians and paramedics provide them. Most NGOs have separate counsellors.

The Urban Primary Health Project, supported by the Asian Development Bank, currently working in four large cities (Dhaka, Chittagong, Rajshahi, and Khulna) is planning to provide services for MR and management of unsafe abortion throughout its 200 clinics (Personal communication, programme managers, December 2002).

A wide network of private providers also exists, ranging from qualified physicians and family welfare visitors to untrained practitioners. Untrained personnel with links to the health system also provide MR, such as: ayahs (female helpers), sweepers and spouses of support staff working in the facilities. There are also traditional providers who provide abortion services. They include kobiraj, homeopathic doctors, village doctors, trained traditional birth attendants and quacks.

Variable quality of care in different menstrual regulation services

The legal status of abortion and social stigma create an environment where proper and wide dissemination of information on safe MR services is not easy. The safety of MR depends on location and income. Considering the fact that in Bangladesh, literacy and income levels are low and that most women live in rural areas, it is easy to understand why so many unsafe procedures occur. In addition, there are a number of factors on the supply side which restrict women’s access to MR services.

The environment in most government facilities is not women-friendly, with little privacy, lack of confidentiality and lack of cleanliness. With the exception of Maternal and Child Welfare Centres and a few newly constructed Health and Family Welfare Centres and NGO clinics, the layout of most government facilities is not conducive to good patient—provider interaction, and most do not have separate recovery rooms. Family Welfare Centres, mostly situated in rural areas and run by female paramedics, have to cope with very high patient loads and few resources. Women’s need for discretion often means they allow unauthorised brokers to persuade them to visit private, and often untrained, providers.

On the other hand, Maternal and Child Welfare Centres are operated under different funding mechanisms, are situated in urban and semi-urban areas and have been enormously strengthened for providing emergency obstetric services. NGO clinics are also mostly situated in urban areas, enjoy more financial and managerial freedom, are run by well-paid, trained doctors, and charge Taka 500—2000 as a service fee.

Providers’ attitudes do not generate much confidence in their patients. Sometimes they are judgmental and impose unnecessary pre-conditions like spousal or parental consent. The attitudes towards MR amongst providers who were interviewed in the government sector varied widely. Some refused to provide MR services on religious grounds, while others refused at public facilities but provided MR services privately. In cases where pregnancy was suspected to be out of wedlock, women often faced hostile behaviour from providers: “Even if one woman dies, ten will be discouraged from being promiscuous.”

In government facilities, MR services are supposed to be free of charge, but unofficial payments are the norm. Women often did not know how much they would have to pay, which created anxiety and acted as a deterrent to using the clinics. Some women had to go to private providers due to the greater distance to government health facilities and transportation costs.

Manual vacuum aspiration (MVA) is usually used for MR in public and NGO facilities. Some NGO facilities have electric vacuum aspiration but do not use it since they do not perform MR beyond 10 weeks. In public facilities, providers do not usually perform MR beyond 12—14 weeks. Private providers reported that they usually take on the later cases and some of them sometime use very crude methods to terminate these pregnancies, especially very late ones. Whatever method is used, the procedure is still called MR by both providers and women. Some managers felt that electric vacuum aspiration could be used at the upazilla level to cater for MR cases beyond 10 weeks, who were often turned away, and for the management of incomplete abortions.

It was not possible for the team to observe an MR procedure in any government facility. In NGO clinics, MR procedures were observed and most providers were technically competent. However, problems were observed with related technical issues. According to government policy, a maximum of 50 procedures should be performed with a standard, single-valve syringe. Only one provider who was interviewed knew this. The team observed that providers were using syringes for more than 100 procedures or “as long as they last”. Examination of aspirated tissue to ensure complete evacuation was not done in any of the government facilities.

Infection control practices varied widely. This is one of the weakest areas at most service facilities. With the exception of Maternal and Child Welfare Centres and NGO clinics, procedure rooms in most facilities were very dirty. There was an acute shortage of gloves and other supplies necessary for infection control, there was no specific allocation of gloves for MR services and gloves were usually washed, dried and re-used without proper processing. In most facilities, utility gloves were not provided to cleaning staff. This poses a risk of exposure to contaminated material. Hand-washing practices are followed everywhere by providers. Savlon solution is used everywhere as the disinfecting agent, but there is no standard protocol that is followed for preparing and diluting the Savlon solution. Most Maternal and Child Welfare Centres and NGO clinics decontaminated instruments with 0.5% chlorine solution. Other government facilities did not follow this procedure at all, while still others did. High-level disinfection of re-usable materials was done by boiling. In Maternal and Child Welfare Centres and NGO clinics, autoclaving was used for metallic instruments and gloves. In many public facilities, however, instruments were kept in open containers without processing. In most of these facilities, waste disposal was not done according to prescribed methods either.

WHO states that the “routine use of antibiotics at the time of abortion has been reported to reduce the post-procedural risk of infection by half. However, where antibiotics are not available for prophylactic use, abortion can be performed”.Citation5 Current government policy in Bangladesh does not recommend routine use of antibiotics post-MR, and antibiotics are not supplied for MR use. However, at all sites antibiotics were routinely prescribed for women post-MR, and in all the training manuals routine use of antibiotics was recommended. Screening for reproductive tract infections and sexually transmitted infections was also done in most facilities and any treatment provided after MR.

Providers, in both the public sector and NGO clinics often asked women to come for a check-up seven days after the MR procedure, and if they had any doubts about completion of the procedure they repeated it. This is known as “check MR”.

Post-MR family planning counselling in government facilities is almost non-existent. Women are routinely given either contraceptive pills or condoms. Most providers interviewed considered that they were the only two methods that could be prescribed safely after MR. Unlike with routine family planning provision, post-MR contraception targets have been set for NGOs, which promote the use of long-term methods and sterilisation. Due to the imposition of targets, counselling in the NGO facilities has become motivational.

There was no information available in the government facilities visited on either post-MR follow-up or post-MR complications. Severe complications are usually managed by doctors, generally using dilatation and curettage (D&C). In some cases, family welfare visitors said that if the patient’s condition permitted it, i.e. if bleeding was not severe, then they would manage the case. “If there is not much product left inside, we wash it by using a size 6 cannula because we are not authorised to do D&C and there is no other equipment.” At this writing, Engender Health is piloting the use of a double-valve syringe for incomplete abortion at selected government facilities.

Regarding quality of care, in spite of any criticisms, it must be said that the MR programme in Bangladesh has come a long way from the time when induced abortions were carried out through the introduction of roots of plants and sharp objects into the cervix and most providers were untrained, traditional providers. According to all the service providers and programme managers interviewed, now that services are available throughout the country with more skilled and trained providers, the use of unsafe objects for inducing abortions has dramatically decreased.

National menstrual regulation training programme

All government and NGO providers are trained and have good theoretical knowledge about MR. However, there have been variations and inconsistencies between the different NGO training programmes in terms of curriculum content, resource persons and the balance between theory and practice. For example, if a clinic does MR up to 10 weeks, training only covers procedures to that point, whereas in other facilities procedures and therefore training can go up to 14 weeks in some cases. This means different providers are obtaining a different level of skills. Thus, some policymakers and health service managers interviewed called for the development of a common, comprehensive training curriculum for MR providers, with supporting manuals. No training and service delivery manuals on MR were available at any of the government facilities, while NGO clinics have their own service delivery manuals and guidelines. Some interviewees also had concerns about the short duration and only basic nature of training in some cases and believed more time was needed to train providers fully.

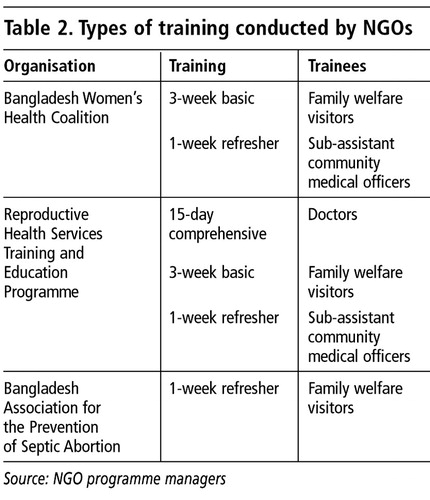

The three main NGOs providing training were the Bangladesh Women’s Health Coalition, Reproductive Health Services Training and Education Programme and Bangladesh Association for the Prevention of Septic Abortion. Length and type of training are shown in .

Prior to the implementation of the HPSP these NGOs had each received funds from SIDA for training. In 1999, with the HPSP, direct SIDA training support to NGOs was withdrawn. However, neither government nor NGOs had experience with the new system of bidding for the contract to provide MR training and services. It took a long time to implement the new process, in which all the NGOs had to bid for only one large contract to do MR training, rather than a number of NGOs applying individually as in the past. Hence, in 1999—2001 NGOs carrying out these functions experienced a funding crisis.

When the bidding process got underway in June 2002, in order to win the bid and also due to inexperience, the winning NGO, the Bangladesh Women’s Health Coalition, submitted a budget that was much lower than actual costs. At the time, they thought they could offset the loss using monies received for other services within their programme. This was not necessarily sustainable on a long-term basis. The Coalition received the contract for the “Safe MR Services and Training Programme” for a period of one year. However, they did not have the capacity to carry out all the training and services nationally, and had to sub-contract to the other NGOs for this, but with less funding, which is likely to have serious consequences for quality of care.

Reporting and record keeping

Previously there were MR registers for family welfare visitors to record information on MR performance. Under the HPSP a Unified Management Information System was introduced. But in most places this system was found to be non-functional, and no new registers were found in any of the government facilities visited. In almost all the facilities at least one mid-level manager had received training on the new system, but in most cases these managers had not trained any other employees in their facilities. Even where employees had received training, they had not received any new registers or forms, and conversely there were places where new forms were available but employees had not received any training.

At the time of the study, family welfare visitors were using old MR registers but even these were not being maintained properly. Information in many columns in the registers was not being entered. Overall, there was no uniformity in recording or with the reporting system. When the team looked at the newly developed UMIS registers, forms and formats, it found that there was no MR register. Moreover, there is no place to record MR service-related information in the daily records. However, in the monthly reporting format there are two columns to record information on number of MR procedures performed and number of MR complications.

Equipment and supplies: consequences of under-reporting

The distribution mechanisms for family planning and MR commodities has remained unchanged under the HPSP. MR kits are distributed on a “pull” basis or in response to a request to the distribution authority. However, since there was significant under-reporting, the “pull” method of distribution is causing a perpetual shortage in the supply of kits and is thereby affecting the quality of service delivery. According to the observations of the assessment team, there was gross under-reporting of MR services and, according to both district and upazilla level managers, some 70% of MR procedures performed were not being reported. This high percentage of under-reporting was also confirmed by some family welfare visitors. According to the managers, this is due to the practice of unofficial payments to public sector providers, who tend to under-report total numbers of MR services in order to avoid sharing this income. Under-reporting is also affecting the availability of other supplies, such as antibiotics, disinfectant, bleach and gloves.

Supervision

Almost all NGOs have strong supervisory procedures, not only administrative but also technical.

In the public sector, under the HPSP, the system of supervision has been adversely affected. Previously there was a definite structure to the system and all concerned personnel knew about their respective positions within the supervisory chain. But since the start of implementation of the HPSP, there has been considerable confusion among personnel about this chain, expressed by service providers as well as managers at all levels who were interviewed. A significant proportion of the personnel interviewed who had supervisory functions said they did not have the required technical skills to supervise or the resources to carry out their supervisory functions effectively, and there were no checklists or tools to use. Most supervisors were male and therefore could not directly observe MR service delivery. There was also a lack of initiative and accountability of managers, which affects supervision. In addition, there is no system of medical audit.

Government—NGO co-ordination

Prior to implementation of HPSP, the MR services and training programme were managed through a number of committees, which played a vital role in maintaining government and NGO coordination. These included the Coordination Committee for MR Agencies in Bangladesh, which included four organisations providing MR—Mohammadpur Fertility Services and Training Centre, Menstrual Regulation Training and Services Programme, Bangladesh Women’s Health Coalition and Bangladesh Association for the Prevention of Septic Abortion. A Technical Advisory Committee was formed with the Director General of Family Planning as its chairman and Director of Maternal and Child Health services as its secretary, to guide the MR provider organisations, a steering committee under the chairmanship of Joint Chief (Planning), Ministry of Health and Family Welfare with the Director MCH, Director PHC, SIDA, World Bank and MR organisations as members.

These committees served as a platform for sharing, learning and advocacy for the MR training organisations. However, under the HPSP none of these mechanisms continued to be functional and an organisation or group to champion the cause of MR no longer exists. Under the HPSP, a coordination mechanism is in operation at the district and upazilla levels but MR service issues were never raised in these meetings. Family welfare visitors, who are the main MR service providers, did not participate in these meetings.

The Bangladesh Women’s Health Coalition, the lead NGO for the Safe MR Service and Training Programme, established a joint coordination mechanism with the other two NGOs, Reproductive Health Services Training and Education Programme and Bangladesh Association for the Prevention of Septic Abortion, which are sub-contractors. Discussions with senior government, NGO, donor representatives and professionals in the field revealed that there was an urgent need to revive the previously existing government—NGO coordination mechanisms.

Conclusions

The MR programme in Bangladesh is a unique programme and has earned a reputation globally in the last three decades. The public sector, being the biggest provider of health care in a country that has to function with major resource constraints, obviously has to face many difficulties. On the other hand the NGOs that provide MR have relatively more freedom in the way they function. The findings of this assessment have to be appreciated in that light.

It was clear from the assessment that the introduction of the HPSP had a negative effect on the MR programme as a whole in three important ways: uncertainty regarding supervision in public sector facilities, disruption of the training component in the NGO sector, and changes in government—NGO coordination. Service provision in part of the NGO sector has also been affected somewhat adversely due to the disruption in the funding mechanism. If these issues can be addressed successfully, the MR programme should be able to continue and hopefully be further improved.

It is intended that the report prepared by the assessment team will be shared with relevant stakeholders as a group and through discussions, to come up with recommendations and an agreed action plan for the programme. Implementation of these recommendations and the action plan will require the active participation and commitment of stakeholders at all levels.

Acknowledgements

This paper is based on the study “The Way Forward: Resourcing the Bangladesh National Menstrual Regulation Programme in the Context of Health Sector Reform”, funded by the UK Department for International Development and Swedish International Development Cooperation Agency and undertaken by the Reproductive Health Alliance, London, UK, and Bangladesh Women’s Health Coalition, Dhaka. The authors would like to thank Peter Hall, former Chief Executive and Sandra Kabir, former Programme Advisor of Reproductive Health Alliance, all national experts, staff members of the Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, members of the senior management of the Bangladesh Women’s Health Coalition, members of the advisory committee, the study team and all the women and men who graciously consented to be interviewed, for their support and cooperation. The report was presented at the Safe Motherhood Conference in Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, 1 October 2003. This paper is a shortened version of the report.

References

- HH Akhter. Abortion: A Situation Analysis. HH Akhter, TF Khan. A Bibliography on Menstrual Regulation and Abortion Studies in Bangladesh. 1996; Bangladesh Institute of Research for Promotion of Essential and Reproductive Health and Technologies: Dhaka.

- Bangladesh Demographic and Health Survey 1999—2000. National Institute of Population Research and Training, Bangladesh, Mitra and Associates, Bangladesh and Macro International USA, 2001.

- S Singh, JV Cabigon, A Hossain. Estimating the level of abortion in the Philippines and Bangladesh International Family Planning Perspectives. 23: 1997; 100–107.

- Ministry of Health and Family Welfare. Health and Population Sector Programme 1998—2003. 1998; MOHFW: Dhaka.

- World Health Organization. Safe Abortion: Technical and Policy Guidance for Health Systems. 2002; WHO: Geneva.

- SNM Chowdhury, D Moni, T Sarkar. A situation analysis of the Bangladesh National Menstrual Regulation Programme Draft report. March 2003.

- HH Akhter. Expanding Access: Mid-level Provider in Menstrual Regulation, Bangladesh Experience. 2001