Abstract

The history of fertility regulation in Romania illustrates the complex interactions between politics, women’s reproductive health and rights and access to high quality care. This paper describes the current situation of abortion and contraception in Romania, based on national statistics, recent reproductive health surveys and the findings of a strategic assessment led by the Ministry of Health in late 2001. This rapid assessment employed a participatory, qualitative methodology. Over 500 people were interviewed from 145 institutions in 25 cities, towns and villages in Romania, about the range of actions needed to prevent unwanted pregnancies, reduce abortion-related morbidity and mortality and improve the quality, accessibility and availability of abortion and contraceptive services. Although much progress has been made in contraceptive services over the past ten years, improvements in abortion care have lagged considerably. The assessment played an important role in raising team members’ awareness and motivation to take action. Some of the issues identified are already being addressed by the institutions that took part. National standards and guidelines for comprehensive abortion care have been developed, contraceptive services have been expanded at primary health care level, sexual and reproductive health education provided by classroom teachers has been introduced in schools, and a study to test a model of comprehensive abortion care services for Romania is planned.

Résumé

L’histoire de la régulation de la fécondité en Roumanie illustre les interactions complexes entre la politique, la santé et les droits génésiques des femmes et l’accèsàdes soins de qualité. Cet article décrit la situation actuelle des services d’avortement et de contraception, sur la base des statistiques nationales, de récentes enquÁtes sur la santé génésique et des conclusions d’une évaluation stratégique dirigée par le Ministère de la santé fin 2001. Cette évaluation rapideàméthodologie qualitative et participative a interrogé plus de 500 personnes dans 145 institutions de 25 villes et villages sur les mesures nécessaires pour éviter les grossesses non désirées, réduire la morbidité et la mortalité liéesàl’avortement et améliorer la qualité, l’accessibilité et la disponibilité des services d’avortement et de contraception. Si les services de contraception ont beaucoup progressé ces dix dernières années, il n’en va pas de mÁme des services d’avortement. L’évaluation a permis d’informer et de motiver les membres des équipes. Les institutions participantes se sont déjÁ attaquéesàcertains problèmes identifiés. Des normes et directives nationales pour des services complets d’avortement ont été définies, les services de contraception ont été élargis au niveau des soins de santé primaires, les écoles ont introduit une éducation sexuelle et de santé génésique, et une étude pour tester un modèle de services complets d’avortement pour la Roumanie est prévue.

Resumen

La historia de la regulación de la fertilidad en Rumania demuestra las complejidades entre la polática, la salud y los derechos reproductivos de las mujeres y el acceso a la atención de calidad. En este artáculo se describe la situación actual del aborto y los servicios de anticoncepción en Rumania, según las estadásticas nacionales, las recientes encuestas de salud reproductiva y los resultados de una evaluación estratégica conducida por el Ministerio de Salud a fines del 2001, que empleó una metodologáa cualitativa participativa. Se entrevistaron a más de 500 personas provenientes de 145 instituciones en 25 ciudades, pueblos y poblados de Rumania, respecto a las medidas necesarias para evitar los embarazos no deseados, disminuir la morbimortalidad relacionada con el aborto y mejorar la calidad, accesibilidad y disponibilidad de los servicios de aborto y anticoncepción. Pese a que se han logrado considerables avances en los servicios anticonceptivos en los últimos 10 años, aún falta mucho por mejorar la atención del aborto. No obstante, gracias a la evaluación, se han formulado normas y directrices nacionales para la atención integral del aborto, se han ampliado los servicios anticonceptivos de primer nivel de atención, se ha institucionalizado la la educación sexual y reproductiva en las escuelas, y se prevé un estudio para poner a prueba un modelo de atención integral del aborto.

Within days of the December 1989 execution of Romanian dictator Nicolae Ceausescu, the new Romanian government overturned the country’s 24-year-old highly restrictive abortion law. First trimester abortions once again became legally available on request, but the high number of women seeking abortions overwhelmed service providers. Although abortion became much safer, quality of care was severely limited by the heavy demand for services. In the early 1990s, the disastrous effects of Ceausescu’s extreme, pro-natalist, anti-family planning policies on women’s sexual and reproductive lives were documented, as well as their need for high quality abortion and contraceptive services.Citation1 Citation2 Citation3 Citation4

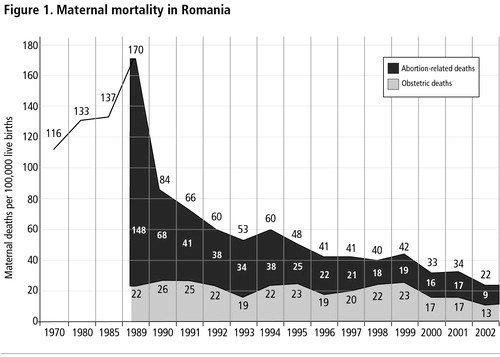

In 1993, national health statistics showed a spectacular decline in maternal mortality from 170 deaths per 100,000 live births in 1989 to 84 per 100,000 in 1990 and 53 per 100,000 by 1993 (Figure 1 ).Citation5 This decline was due almost entirely to the decrease of abortion-related mortality (both induced and spontaneous) from 148 per 100,000 live births in 1989 to 58 in 1990 and 34 in 1993. A national reproductive health survey documented exceptionally low rates of contraceptive prevalence and the highest abortion rate in the world from 1990-92, 182 abortions per 1,000 women of reproductive age.Citation6 Although the official number of abortions decreased significantly during the 1990s, the overall abortion rate today remains relatively high, with many more abortions now performed in the private sector, where an estimated 20% go unreported to the Ministry of Health.Citation7 The quality of abortion care in public facilities remains poor; illegal, unsafe abortion is still found in some rural areas and after nearly a decade of externally funded family planning assistance, post-abortion contraceptive services are still virtually non-existent.Citation8

In an effort to develop new strategies and policy and programmatic interventions to address these challenges, in November 2001 the Romanian Ministry of Health (MOH) in partnership with the World Health Organization (WHO) conducted a strategic assessment of abortion and contraception in Romania. Employing a participatory, qualitative methodology, the assessment complemented (and indeed corroborated) recent surveys, which show that although much progress has been made in increasing the prevalence of modern contraception, overall use remains relatively low by European standards, and abortion continues to exact an unnecessarily high cost on Romanian health services.Citation8, Citation9 In this paper, we report key findings from the strategic assessment and review progress made in Romanian sexual and reproductive health over the past decade and ongoing challenges.

Historical context of abortion in Romania

Abortion was first legalised in Romania in September 1957 following legal changes in the Soviet Union and other central and east European countries. Liberalisation of the law led to both high rates of legal abortion and sharp decreases in illegal procedures.Citation10 In October 1966, the new Ceausescu government, concerned about declining fertility and population growth, reinstated abortion restrictions.Citation11 Decree 770 stated that abortion would only be allowed for women:

| • | who had given birth to and raised four or more children, or were over 40 years of age | ||||

| • | who suffered from (or had a spouse who suffered from) a severe hereditary disease that might be transmitted and/or cause severe congenital malformations | ||||

| • | who had severe physical, psychological or sensory disabilities that would prevent them from caring for the newborn | ||||

| • | whose life was endangered by the pregnancy, or | ||||

| • | whose pregnancy was the result of rape or incest. | ||||

In spite of an initial rise in fertility, the government decided the restrictions had to be even more stringent to produce the desired population increase. In 1985, the eligibility criteria were further narrowed to five children or more per woman and the minimum age for abortion raised to 45 years. As a result, abortion-related deaths in 1989 accounted for 87% of all maternal mortality.Citation5 In sharp contrast, abortion-related mortality stood at 9 per 100,000 live births in 2002.Citation12 From 1990—92 Romania had approximately three abortions for every live birth, and clinics were overwhelmed with women seeking services. Individual providers reported performing 40 or more abortions per day and in some hospitals there were as many as three women per bed waiting for or recovering from abortion.Citation4, Citation5 Baban and Kligman have written compellingly about the deaths and suffering caused by Ceausescu’s policies.Citation13, Citation14

The end of the Ceausescu regime opened the doors to foreign assistance. A major loan from the World Bank provided funding for the MOH to implement a national programme to improve reproductive health.Citation15 Although progress has been uneven at times, the Romanian family planning programme is considered one of the greatest success stories of the former Soviet bloc countries. Initially, the MOH opened and equipped 11 family planning referral centres (most of them located in maternities or regional hospitals) and 230 family planning offices (located in hospitals, polyclinics or dispensaries). It also established a Family Planning and Sex Education Unit in the Maternal and Child Health Department of the MOH. This unit was responsible for monitoring and evaluation of the newly opened family planning clinics; contraceptive security and procurement; development of a national information, education and communication programme; development of the family planning training curricula for nurses and medical students; and training of obstetricians and general practitioners (GPs) for family planning competence (speciality). The loan also provided for purchase of new medical equipment, including electric vacuum aspiration pumps for performing abortions for the major hospitals located in the judet (county) capitals. However, service contracts were not renewed and spare parts were not provided in subsequent years. The majority of abortions in the early 1990s continued to be performed with dilatation and curettage (D&C).

During the 1990s donor organisations, including the United States Agency for International Development (USAID) and UNFPA, provided millions of dollars worth of contraceptive commodities and provider training. A distinctive component of Romania’s new policy on family planning is the focus on GPs rather than gynaecologists to provide contraceptive counselling and methods, especially in rural areas. Since 2001 the MOH, in collaboration with UNFPA and JSI Research and Training Institute (USAID-funded) have been training family doctors to provide family planning services. By the end of 2003, 2,300 of approximately 15,000 family doctors had been trained along with 1,750 nurses.Citation16

Today the Romanian family planning network consists of approximately 250 clinics located in major cities and staffed by GPs with specialist training in family planning and an expanding network of specially trained family physicians in rural and urban areas. The MOH has also implemented a programme that provides free contraceptives to poor and disadvantaged women and has invested a large amount of national funds in procuring contraceptives, to make up for decreasing contraceptive donations from abroad.

The abortion ratio declined by 85% from 1990 to 2002. Contraceptive prevalence for women in union aged 15—44 (traditional and modern methods) increased from 57% in 1993 to 64% by 1999. Modern method use in the same group and time period increased from 14% to 30%. However, prevalence of modern methods for all women aged 15—44 remained low at 23.3% in 1999.Citation9 The primary traditional family planning method in Romania is withdrawal.Citation9

The Young Adult Reproductive Health Survey in 1996 documented low knowledge of reproductive health issues among women and men aged 15—24 and an overwhelming desire to receive sex education in school.Citation17 Following dissemination of the survey findings, recommendations were made to the MOH, Ministry of Education and international donors to develop a school-based sex education programme in Romania that would further strengthen the efforts some medical professionals had been making in schools since 1991. In 1998 the MOH completed an operational plan for reproductive health promotion,Citation18 but it was not until 2000 that teaching of sex education in schools by medical professionals was formally approved and published in the Official Monitor. Citation19

Today, given women’s low fertility preferences, the Ministry of Health still considers national contraceptive prevalence low and the annual number of abortions high, resulting in unnecessary morbidity and high costs to the health care system. In addition, Romania continues to have a comparatively high number of illegal (and unsafe) abortions. In 2002 there were 147 illegal abortions officially reported (which likely represents substantial under-reporting) compared to 187,852 reported legal induced abortions.Citation12 This situation led the MOH to request assistance from WHO to carry out a strategic assessment of the complex policy and programme issues that surround abortion and contraception in Romania. This was also seen as a key component in a broader effort to develop a national strategy for sexual and reproductive health.

Conducting the strategic assessment

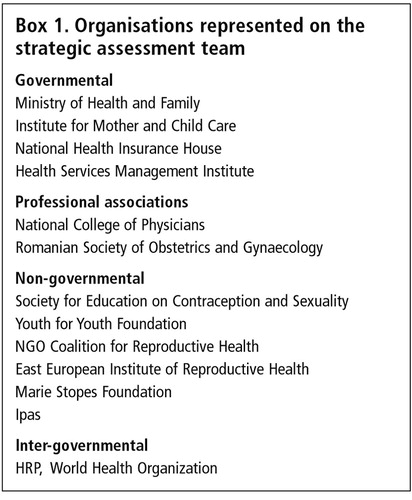

A strategic assessment is the first of a three-stage conceptual framework and strategic planning methodology known as the Strategic Approach, developed by the UNDP/UNFPA/WHO/World Bank Special Programme of Research, Development and Research Training in Human Reproduction (HRP) at WHO.Citation20 The assessment was led by the Romanian MOH. A team of 23 members representing a broad range of stakeholders from governmental and non-governmental organisations conducted the fieldwork (Box 1).

Following the development of a background paperCitation7 reviewing national studies and service delivery statistics, a national planning workshop of key stakeholders was convened in Bucharest to gain input into the development of strategic questions, the fieldwork process and locations. Following the meeting, the assessment team spent several days refining interview guides and finalising logistical arrangements for the fieldwork.

Three strategic questions guided the assessment process:

| • | How can abortion-related morbidity and mortality be further reduced? | ||||

| • | How can quality of care and choice in abortion services be improved? | ||||

| • | How can unwanted pregnancies and thus the need for abortion be further reduced? | ||||

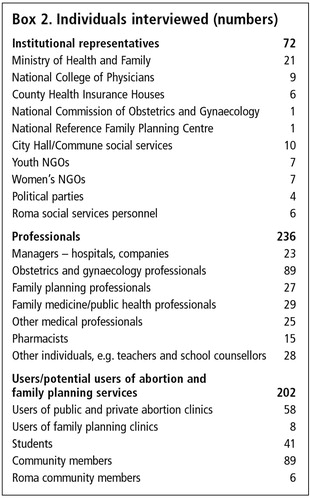

In a two-week period in November 2001, team members conducted observations and over 500 in-depth interviews about fertility regulation with a convenience sample, including programme managers, providers, users of services and community members (Box 2). The fieldwork included visits to 21 public hospitals, 13 private abortion clinics and numerous other community-based institutions and organisations in the capital Bucharest and two to four cities, towns, villages and communes each in eight counties across Romania — Braila, Constanta, Dolj, Hunedoara, Iasi, Mures, Teleorman and Vaslui. The geographic areas and institutions visited were selected purposively by MOH officials to reflect different cultural and socio-economic conditions. Although the findings cannot be considered statistically representative they were highly revealing.

To understand why abortion-related morbidity and mortality continues, team members interviewed stakeholders about access to and availability of services, and quality of contraceptive and post-abortion contraceptive counselling and methods, especially in rural areas, including youth-friendly abortion, contraceptive, and post-abortion contraceptive services. To assess quality and choice in abortion and contraceptive services, team members interviewed service users and providers about their needs and experiences. Providers were asked about pre-service and in-service training, abortion techniques, and instruments and supplies available and required to provide safe services. The users of services were asked for their perspectives on quality, choice and acceptability of services. To understand how to reduce unwanted pregnancy, team members interviewed stakeholders about sex education in primary and secondary schools.

Data analysis involved nightly group discussions, and indeed debates, about each team member’s findings and experiences. The daily process of analysis helped to develop a consensus on findings and a coalition for implementing recommendations. The findings were presented in a draft report and presentations made in a national dissemination workshop, attended by many of the stakeholders from the first planning workshop and others identified during fieldwork. Input from workshop participants was incorporated into the report, which was finalised and distributed to programme managers, administrators, NGOs and policymakers.Citation8

Key findings and recommendations

In addition to corroborating many of the findings from previous reproductive health surveys and research, Citation1 Citation4 Citation6 Citation7 Citation9 Citation13 Citation14 Citation17 especially those showing limited access and often low quality of care, the strategic assessment challenged some widely held assumptions — e.g. use of vacuum aspiration for termination of pregnancy was in fact not widespread and quality of care in abortion services had not always improved substantially over the last decade. This helped government policymakers formulate new strategies and interventions focused on contraception and abortion provision. The findings did not vary greatly between the five regions visited; however, it was obvious to team members that the rural areas were vastly under-served.

Access to and availability of services

Most gynaecologists interviewed said they performed far fewer abortions now than in the early 1990s. However, despite major successes in the national family planning programme since 1993, abortion remains one of the most common methods of fertility control in Romania.Citation6, Citation8, Citation9 As documented in the early 1990s, most providers and women still consider abortion to be “a traditional, safe, accessible, quick and relatively cheap procedure”.

A rate of 32 abortions per 1,000 women of reproductive age in 2002 suggests an ongoing cultural preference for abortion and continued unmet need for both routine and post-abortion contraceptive services.Footnote* Although more available now than in the early 1990s, contraceptive services remain relatively difficult to access for young people, rural residents and women and men with lower educational and socio-economic status, especially when compared to the availability and acceptance of abortion. Some women told interviewers that they would prefer to have one abortion every few years than use contraceptives on a daily basis. This may reflect Ceausescu-era myths about the dangerous side effects of contraception that continue to pervade less educated, lower socio-economic groups in Romania, as well as the low cost of abortion relative to contraception.

Access to contraceptive services was more limited in rural areas since most family planning clinics are still located in urban areas and family doctors are just now being trained and equipped to provide these services. Young people reported that youth-friendly services were virtually non-existent, even in urban areas.

Interviews conducted with family doctors showed that some still felt uncomfortable about or ill-equipped to provide contraceptive services. Family doctors have only been trained to provide oral and injectable contraceptives and condoms. Women who want an IUD can still only obtain it from a gynaecologist, despite repeated efforts by women’s health advocates to convince the MOH to allow provision of IUDs by other trained providers. Men who desire a vasectomy have even more limited options, as there are only a very small number of trained providers.

Abortions are widely available in Romania and by law are provided exclusively by gynaecologists in both public and private facilities. However, nearly all public sector obstetrics—gynaecology departments and private abortion clinics are located in urban areas. Again, the urban population has a much wider range of services and choices than the rural-based population. The assessment team found that travel expenses can easily double the cost of abortion for women living in rural areas.

Rural, less affluent and less educated women continue to be at risk for unsafe abortion in Romania, but, in 1999, in stark contrast to pre-1990, fewer than 1% of reported abortions were performed outside the formal health system.Citation9 Assessment team members interviewed a woman in a Roma community who freely admitted to performing 25 abortions on herself with a pen; all completed, she said, with no complications. She was interviewed while accompanying her 27-year-old daughter, who was having her eighth hospital-based abortion. An ambulance driver in another judet reported that he had picked up three women suffering from complications of unsafe abortion in the previous year.

There are few if any post-abortion contraceptive services available and minimal links or referrals to other reproductive health services.

Cost of services

Elective abortion is not reimbursed by the national health insurance system, but both public and private facilities provide terminations for a nominal fee. The official fee for an abortion in a public clinic has changed very little in ten years, considering inflation. At the time of the assessment it was approximately 60,000 lei (US$2). In 2004, the price was doubled by the Ministry of Health in conjunction with offering free contraceptives to women who had abortions, in an effort to discourage the non-use of contraception, as well as to recover more of the true cost of the services.

However, as was the case ten or more years ago, many women still feel obliged to provide a gift (money or otherwise) to their abortion provider following receipt of services, though these may or may not improve quality of care.

A factory executive who has had five abortions said:

“All women fear abortion and have anxiety about it. They fear the money aspect of abortion, [that is, the process of making additional “unofficial” payments]. Only after the money do they think about the health aspects. Prior to 1990, women were afraid they would die from abortion.”

The practice of offering gifts to doctors following abortion probably results from a complex interplay of factors. The historical context of abortion, especially from the Ceausescu era, is still strong in the minds of many older Romanian women, and perhaps through oral histories, in the minds of their daughters as well. During that time doctors often put themselves at great risk by performing abortions, and all payments for services were “unofficial”. Cultural traditions and practices of offering money or gifts in kind to doctors to express gratitude and in hopes of preferential treatment also occur with other medical procedures (e.g. general surgery). Historically, low pay for doctors and other medical personnel has been well recognised by the public, and some unofficial payments may be genuine tokens of appreciation for what is often perceived as a difficult and unpleasant job. Certainly, some doctors continue to play on women’s fears of abortion to exact a bigger gift.

Low pay for doctors and poor quality in the public health system continue to encourage unofficial payments for abortion. In some areas, these make abortions in the public sector more expensive than in some private practices. Some gynaecologists admitted that abortion was a good source of income (and other gifts in kind), especially for those who primarily do abortions. But this may be slowly changing, as one provider so insensitively noted:

“Abortion is a milking cow, but doctors are now discovering that there are other ways to make money, such as ultrasound, menopause therapies, pap smears and even contraception.”

Generally, women know that public sector abortion fees do not cover the real cost of services and that private abortion fees more accurately reflect the true cost of abortion. Based on a recent cost study, the real cost of abortion to the health care system varied from 150,000—450,000 lei (US$5—15) in the public sector to 350,000—1 million lei (US$12—33) in private practice. The total cost depended on the duration of pregnancy, pain medication used, whether any complications occurred, the time for the procedure and overall time spent in the clinic, and clinic overheads.Citation7 The price women pay varies between public and private facilities, different hospital departments and private facilities due to considerable institutional autonomy in setting fees. Currently, the government has no authority to regulate fees charged in the private sector.

Women entitled to free abortion services include those with four or more children, students, pupils, and those who are unemployed or without income. However, the assessment team found that many women eligible to receive free services ended up paying, either because they could not demonstrate their economic status or, in some cases, simply did not know they had a right to free services.

The majority of the women interviewed during the assessment thought that both abortion fees and the cost of contraceptives were too high in comparison to their disposable income — despite the fact that the gross monthly salary in 2001 was 5,300,000 lei (US$177).Citation21 Providers, women having abortions and other community members interviewed worried that increased abortion fees could lead once again to more unsafe abortions among the poorest Romanian women.

The assessment team recommended reassessing abortion fees, taking into consideration the actual cost, the impact of cost on demand and special criteria for exemptions and insurance cover. In order to mitigate concerns about unsafe abortion and other sensitivities stemming from Romania’s long history of unsafe abortion under Ceausescu, the team recommended that the MOH set the abortion fee for the public health care system at a level that avoided an increase in illegal, unsafe abortions. It was also recommended that at least some of the funds derived from abortion services should be reinvested to improve the quality of services, including post-abortion contraception.

The assessment also showed that a key barrier to accessing contraception was cost relative to the price of abortion. For example, oral contraceptives cost women approximately 60,000 lei (US$2) per month. Emergency contraception is known and used by a relatively small number of women, although it has been available in most family planning clinics since 1990. In 2001, a special two-levonorgestrel-tablet packet of emergency contraception cost approximately 120,000 lei (US$4), which at the time was double the official fee for abortion.

Quality of care

The assessment team noted poor quality of care in various components of contraceptive and abortion services. For example, team members observed doctors either re-using or not using gloves during procedures, including one who did not wash his hands immediately following an un-gloved procedure. According to an unpublished study reported in the background paper, just over half of Romanian doctors continue to use D&C rather than vacuum aspiration.Citation7 This finding was borne out in the assessment, where it was observed that many facilities either did not have vacuum aspiration technology or else the equipment was broken or only available for use by the head gynaecologist. Most doctors observed who did use vacuum aspiration followed it with a metal curette check of the uterus and rarely if ever examined the products of conception for completeness of the procedure.

The concept of comprehensive abortion care does not exist in Romania. Team members observing services also noted that doctors provided little if any information to women about the procedure, return to fertility, signs and symptoms of complications or post-abortion contraception, and rarely encouraged women to return for follow-up. Procedure tables often had no linens and were not cleaned between procedures; there was often more than one woman per bed; and there was general inattention to basic human needs and privacy. Infection prevention practices were uneven at best and in many centres very poor. Pain management practices observed ranged from no anaesthesia to heavy sedation with intravenous anaesthesia; however, most procedures were usually performed with local paracervical anaesthesia. There was little or no screening or referrals for reproductive tract infections or other reproductive health services.

In addition, some providers reported that post-abortion complications (primarily incomplete evacuations that result in prolonged bleeding and infection) occurred in approximately 10% of cases. This high number corroborates figures cited in both the 1993 and 1999 reproductive health surveys.Citation5, Citation9

Most providers knew relatively little about medical abortion (mifepristone + misoprostol), which is not yet available in Romania. However there is interest in this method, and many providers and women said that it could be a very good option that should be further explored. In a WHO clinical trial of medical abortion conducted in Târgu-Mures in 1999, there was overwhelming demand from women to join the study so that they could take pills for abortion rather than have a surgical procedure. One desperate woman even tried to offer investigators a gold bracelet to participate.

Unlike the situation in family planning services, the concept of “rights” for women seeking an abortion does not exist in public sector abortion services. A professional woman told interviewers that she had no idea what her “rights” included. As far as she was concerned, “You have to pay for your rights” despite there actually being a law in Romania regarding the rights of the patient.

Finally, there is no functional monitoring and evaluation system in Romania to ensure ongoing quality of abortion services. Assessment team members agreed these were important, but some noted the cost and potential provider resistance to such a programme. Other recommendations for improving quality of care included the development of national standards and guidelines including recommendations to replace D&C with vacuum aspiration for all first-trimester abortion procedures, more comprehensive abortion care, including post-abortion contraceptive counselling, screening and referrals for other health needs, and the introduction of medical abortion.

Preventing unplanned pregnancy and the need for abortion

Interviews with students, teachers and school administrators suggested that while there was still resistance by some (perhaps many) parents to providing information in schools about sexual and reproductive health, it is necessary to combat both unplanned pregnancies and exposure to sexually transmitted infections. Team members were encouraged to find that attitudes about contraceptive use among young people were more positive than among members of their parents’ generation.

Nowhere during the fieldwork did the assessment team find doctors counselling or even discussing contraceptive use following abortion, and in only a few places were women referred to family planning clinics. However, JSI has recently funded the East European Institute of Reproductive Health to study the feasibility and cost of linking contraception and abortion services.

Conclusion

Recurrent themes in the strategic assessment included the pervasive effect of poverty and lack of access to services on women’s sexual and reproductive health; the lack of quality information and counselling; the historical context of women’s fear of abortion and contraception; and the need to improve nearly all dimensions of quality of care, especially in abortion services. Increasing access to contraception and lowering the price of modern contraceptives relative to abortion might facilitate a change in attitudes and behaviour towards greater contraceptive use. Pairing the availability of free or subsidised contraceptives on a large scale with ongoing information campaigns on the benefits of modern contraception may lead to both increased demand and use. At the same time, strengthening the MOH policy of expanding access to contraceptive services in rural areas and ensuring that the cost of abortion never becomes a barrier to any woman seeking services should help to discourage women from resorting to illegal, unsafe abortion when unwanted pregnancies do occur.

The strategic assessment played an important role in boosting government motivation to take action. The participatory nature of the assessment, including the involvement of high-level programme managers, enabled consensus and action on a number of important policy issues. For example, the MOH is now more active in expanding contraceptive services to the primary care level, training family physicians and nurses in rural areas to provide contraception and making free or subsidised contraceptives available to women. A new information, education and communication campaign has been designed specifically to inform eligible women about the availability of free contraceptives. The MOH has earmarked considerable budget funds since 2002 for purchasing contraceptives to be provided free of charge to eligible women, including the rural poor and those who undergo abortion on request in a public health unit. The National Health Insurance House included oral and injectable contraceptives on its list of reimbursable drug costs, although they were withdrawn after seven months on the list.Citation22

As a result of the assessment, the Obstetrics and Gynaecology Speciality Care Rehabilitation Programme in Romania stipulates that all public obstetrics—gynaecology hospital departments should ensure safe and quality abortion services, including counselling and post-abortion contraception,Citation23 and that the fee for public sector abortion services cannot exceed the amount set by the MOH, so as not to limit women’s access to services. National standards and practice guidelines for safe abortion care were developed by the MOH, College of Physicians, and Society of Obstetrics and Gynaecology recommending the use of manual or electric vacuum aspiration for termination of pregnancy.Citation24 The regional and local structures of the MOH, National Health Insurance House and College of Physicians are responsible for the implementation and monitoring of the national decisions. A pilot intervention on comprehensive abortion care was also designed and partially funded.

The MOH signed an agreement with the Ministry of Education and Research for the mandatory introduction of health education, taught by teachers rather than medical professionals, in Romanian schools starting in 2003, including reproductive health education.Citation25 In March 2003, the MOH launched the first national Strategy for Sexual and Reproductive Health.Citation26 Informed by the strategic assessment, it highlights comprehensive family planning and safe pregnancy termination services as key areas requiring programmatic intervention. In late 2004, the Romanian Parliament approved the Reproductive Health Law, which sets out clear principles regarding contraception and abortion.

These and other initiatives demonstrate concerted efforts by the MOH, other governmental institutions, local and international NGOs and donors to improve reproductive health services in Romania. Although there remains a strong abortion culture in Romania, prevention of unwanted pregnancy is becoming increasingly important to policymakers and the public.

Acknowledgements

The November 2001 strategic assessment of abortion and contraception in Romania was funded primarily by WHO HRP, with additional technical and financial support from the MOH, local collaborating institutions and Ipas. We thank our fellow assessment team members Cãtãlin Andrei, Radu Belloiu, Cosmina Blaj, Ionela Cozos, Daniela Drăghici, Monica Dunarinu, Diana Gheorghiă, Virginia Ionescu, Borbala Koo, Dan Aurelian Lăzărescu, Luminia Marcu, Doina Ocnaru, Alina Petrescu, Mihaela Zoe Poenariu, Cristian Posea, Silviu Predoi, Florina Prundaru, Lia Rugan, Entela Shehu, Raluca Teodoru, and Adrian Văduva. We also thank Traci Baird, Janie Benson and Henry David for thoughtful comments on the draft manuscript.

Notes

* Although no data were collected on repeat abortion, many women interviewed acknowledged having more than one abortion.

References

- World Health Organization. Report on a mission to Romania, 29 December 1989 — 15 January, 1990. 1990; WHO: Geneva.

- C Hord, HP David, F Donnay. Reproductive health in Romania: reversing the Ceausescu legacy Studies in Family Planning. 22: 1991; 231–240.

- BR Johnson, M Horga, L Andronache. Contraception and abortion in Romania Lancet. 341: 1993; 875–878.

- BR Johnson, M Horga, L Andronache. Women’s perspectives on abortion in Romania Social Science and Medicine. 42(4): 1996; 521–530.

- Ministry of Health Romania, Centre for Health Statistics. National Maternal Mortality Statistics. 1993; MOH: Bucharest.

- Institute for Mother and Child Care, Ministry of Health and Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Reproductive Health Survey, Romania 1993: Final Report. 1995; CDC: Atlanta.

- M Horga. Contraception and abortion in Romania: background paper for the strategic assessment of policy, programme, and research issues related to pregnancy termination in Romania. 2001Unpublished

- World Health Organization. Abortion and Contraception in Romania: A Strategic Assessment of Policy, Programme, and Research issues. Geneva: WHO. (In press).

- F Serbanescu, L Morris, M Marin. Reproductive Health Survey Romania, 1999: Final Report. 2001; Association of Public Health and Management and CDC: Bucharest, Atlanta.

- KH Mehlan. Legal abortions in Romania Journal of Sex Research. 1(31): 1965.

- HP David, NH Wright. Restricting abortion: the Romanian experience. HP David. Abortion Research: International Experience. 1974; Lexington Books: Lexington MA, 217–225.

- Ministry of Health Romania, Centre for Health Statistics. National Maternal Mortality Statistics. 2002; MOH: Bucharest.

- A Baban. Romania. HP David. From Abortion to Contraception: A Resource to Public Policies and Reproductive Behavior in Central and Eastern Europe from 1917 to the Present. 1999; Greenwood Press: Westport CT, 191–221.

- G Kligman. The Politics of Duplicity: Controlling Reproduction in Ceausescu’s Romania. 1998; University of California Press: Berkeley.

- World Bank. Health Rehabilitation Project (for Romania). Project ID P008759. Signed 1 October 1991.

- John Snow, Inc. Romanian Family Health Initiative. http://www.jsi.com/JSIInternetProjects/InternetProjectFactSheet.cfm?dblProjectID=1633

- F Serbanescu, L Morris. Young Adult Reproductive Health Survey, Romania, 1996: Final Report. 1998; International Foundation for Children and Families and CDC: Bucharest, Atlanta.

- Ministry of Health Romania. 1998 Reproductive Health Promotion: Operational Plan 1998—2003. 1998; MOH: Bucharest.

- Ministry of Education and Ministry of Health Romania. Official Monitor Nr. 385 din 08/17/2000, Annex I, B.

- World Health Organization Department of Reproductive Health and Research. The Strategic Approach to Improving Reproductive Health Policies and Programmes: A Summary of Experiences. 2002; WHO: Geneva.

- National Institute of Statistics Romania. 2001; National Bank of Romania: Bucharest.

- Ministry of Health Romania and National Health Insurance House. Order 72/44/8.02.2002. Official Monitor 126/02.18.2002.

- Government of Romania. Decision No. 534 [Approving the strategy regarding the rehabilitation and reorganisation of the specialty hospital medical assistance in obstetrics and gynaecology and neonatology, for the 2002-2004 period]. Bucharest, 30 May 2002.

- Ministry of Health Romania. Standards and Practice Recommendations for Performing Elective Pregnancy Termination. June 2003. MOH: Bucharest.

- Collaboration Protocol between the Ministry of Health and the Ministry of Education regarding the development of the National Programme of Education for Health in the Romanian school system. Bucharest, December 2001.

- Ministry of Health Romania. National Sexual and Reproductive Health Strategy. 2003; MOH: Bucharest.