Abstract

Unsafe abortion and associated morbidity and mortality in women are completely avoidable. This paper reports on an analysis of the association between legal grounds for abortion in national laws and unsafe abortion, drawing on an unpublished study and using estimates of the incidence of and mortality from unsafe abortion using information from the sources used to estimate the incidence of unsafe abortion and associated mortality in 2000. Although legal grounds alone may not reflect the way in which the law is applied, nor the quality of services offered, a clear pattern was found in more than 160 countries indicating that where legislation allows abortion on broad indications, there is a lower incidence of unsafe abortion and much lower mortality from unsafe abortions, as compared to legislation that greatly restricts abortion. The data also show that most abortions become safe mainly or only where women’s reasons for abortion, and the legal grounds for abortion coincide. This is a compelling public health argument for making abortion legal on the broadest possible grounds. A wide range of actions have formed part of national campaigns for safe, legal abortion over the past century, covering law reform, provision of safe services, ensuring quality of care, training for providers and information and support for women. Safe abortion is an essential health service for women, as essential for sexual and reproductive health as safe contraception, and safe pregnancy and delivery care. In spite of sometimes powerful opposition and terrible setbacks, the public health imperative is gaining ground in many parts of the globe.

Résumé

Les avortementsàrisque et la morbidité et mortalité qu’ils entraînent ne sont pas une fatalité. Cet article analyse l’association entre les indications légales de l’avortement dans les législations nationales et les avortementsàrisque, se fondant sur une étude non publiée des estimations de l’incidence des avortementsàrisque et de la mortalité qu’ils provoquent. Si les motifs légaux ne peuvent seuls refléter la manière dont la loi est appliquée, pas plus que la qualité des services proposés, un modèle a clairement été observé dans plus de 160 pays: les législations prévoyant de nombreuses indications pour l’avortement vont de pair avec une incidence inférieure d’avortementsàrisque et une mortalité liée nettement plus faible que les législations restrictives. La plupart des avortements deviennent s rs lorsque les raisons qui poussent les femmesàavorter coéncident avec les motifs légaux d’avortement. C’est lÁ un argument de poids pour légaliser l’avortement le plus largement possible. Au siècle dernier, les campagnes nationales ont utilisé des mesures très variées pour légaliser et médicaliser l’avortement, notamment réformer la législation, garantir des services s rs et la qualité des soins, former les prestataires, informer et soutenir les femmes. Des avortements sans risque constituent un service de santé essentiel pour les femmes, aussi essentiel pour leur santé génésique qu’une contraception et des soins obstétriques adaptés. Malgré une opposition parfois puissante et de terribles revers, cet impératif de santé publique gagne du terrain dans de nombreuses régions du globe.

Resumen

El aborto inseguro y la morbimortalidad materna atribuible a éste son completamente evitables. En este artáculo se informa acerca de un análisis de la asociación entre las causales del aborto permitidas por las leyes nacionales y el aborto inseguro, basado en un estudio inédito cálculos de la incidencia de la mortalidad atribuible al aborto inseguro. Aunque las causales legales por sá solas no reflejan la forma en que se aplica la ley, o la calidad de los servicios prestados, se encontró un patrón concreto en más de 160 paáses, que indica que en los lugares donde la ley de aborto es más liberal, se observa una menor incidencia de aborto inseguro y una tasa mucho más baja de mortalidad debido a éste. Por tanto, la mayoráa de los abortos son seguros principalmente cuando coinciden los motivos de las mujeres para interrumpir el embarazo y las causales legales para ello. Áste es un argumento convincente para legalizar el aborto bajo las causales más amplias posibles. En el último siglo se han tomado diversas y numerosas medidas a nivel nacional en pro del aborto legal y seguro, tales como la reforma de leyes, la prestación de servicios seguros, la garantáa de la calidad de la atención, la capacitación de los profesionales de la salud y el suministro de información y apoyo para las mujeres. El aborto seguro es tan esencial para la salud sexual y reproductiva de las mujeres como la anticoncepción segura y la atención segura durante el embarazo y el parto. Pese a la oposición, a veces poderosa, y a terribles contratiempos, el imperativo en salud pública está ganando terreno en muchas partes del mundo.

Reducing the public health problem of unsafe abortion is one of the most important goals of the Programme of Action of the International Conference on Population and Development (ICPD) 1994. Ten of the 20 years in which to achieve that goal have already passed. Improving maternal health, through reducing maternal mortality by two-thirds by the year 2015, is one of the eight Millennium Development Goals. Deaths from the complications of unsafe abortion constitute 13% of all maternal deaths.Citation1 Making abortion safe for women will be a crucial part of achieving this Millennium Development Goal as well.

Unsafe abortionFootnote* and associated morbidity and mortality in women are completely avoidable. Existing data and a growing number of studies, including those in the publication in which this paper appears, seem to indicate that slow but steady progress is being made to reduce unsafe abortions and to reform abortion law, policy and practice to benefit women’s health and lives around the world. In the year 2000, the most recent year for which information is available, there were an estimated 19 million unsafe abortions, almost all in developing countries. However, compared with 1995, the data from 2000 appear to show a decline in the unsafe abortion rate for all developing country regions except South-central Asia and northern Africa. The number of deaths from complications of unsafe abortion also appear to have declined, from an estimated 78,000 in 1995 to an estimated 68,000 in 2000.Citation1

Legal grounds for abortion, unsafe abortion and abortion-related deaths

Evidence from more and more countries is accumulating to show that when abortion is legal on broad socio-economic grounds and at a woman’s request, and when safe, accessible services have been put in place, unsafe abortion disappears and abortion-related mortality and morbidity are reduced to a minimum. This has been shown in the United States in the 1970s and in Romania and South Africa in the 1990s, and well documented in data.Citation3 Citation4 Citation5 Until now, however, there has not been a systematic examination across countries of the association between national laws on abortion, the incidence of unsafe abortion and abortion-related deaths.

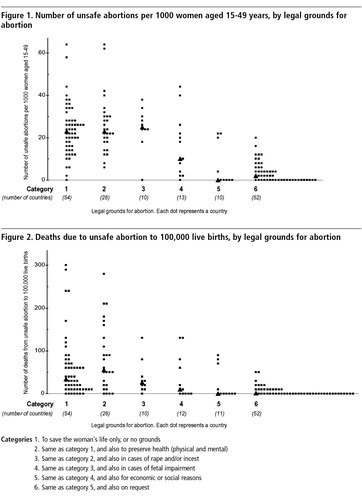

This paper reports on an analysis of the association between legal grounds for abortion in national laws and unsafe abortion, using information from the sources used to estimate the incidence of unsafe abortion and associated mortality in 2000. The more than 160 countries included were those for which both legal information and unsafe abortion estimates were available. Data on the population of women aged 15—49 in these countries were taken from the United Nations Population Division data,Citation6 as were data on the legal status of abortion.Citation7 The grounds for legal abortion in national laws were divided into six categories, ranging from highly restricted to available on request (see key to Figures 1 and 2).

The six categories are cumulative rather than mutually exclusive. This means that for countries included in category 3, where abortion is legal in cases of rape and/or incest, abortion is also legal on the grounds in categories 1 and 2, to save the life and preserve the health of the woman. Similarly, countries allowing abortion on request also allow all the grounds in categories 1 through 5. This is the case for almost all of the 167 countries included in the analysis of unsafe abortion rates and the 165 countries where abortion-related mortality was examined. It is not the case in four of those countries where, although abortion is legal for pregnancies resulting from rape and/or incest, it is illegal for preserving the health of the woman. These four countries are, however, included in category 3. The three countries where abortion is illegal under all circumstances are included in category 1.

Figure 1 demonstrates a clear association between the legal grounds for abortion and the unsafe abortion rate. It shows that the median rate of unsafe abortions per 1,000 women is 23 in the countries in category 1 (54 countries), 23 in the countries in category 2 (28 countries) and 25 in the countries in category 3 (10 countries). This is the case even though the rate of unsafe abortion varies greatly both in the 54 countries in category 1 (from 0 to 65) and in the 28 countries in category 2.

The unsafe abortion rate only begins to change in the 13 countries in category 4, which also allow abortion in cases of fetal impairment, where the median rate of unsafe abortions has dropped to 10 per 1,000 women of reproductive age. The contrast is even more marked in the countries that also allow abortion for economic or social reasons (10 countries) or on request (52 countries), where the unsafe abortion rates are a median of 0 and 2 per 1,000 women, respectively.

Mortality from unsafe abortion is also clearly affected by the legal context (Figure 1). While the median mortality ratio is 34 to 100,000 live births in category 1 countries, where abortion is allowed only to save the woman’s life (or not allowed at all), there are countries where the ratio is as high as 300 to 100,000 live births. Where abortion can be practised to save the woman’s life and preserve her health, the median is somewhat higher at 55. The mortality ratio then declines with each additional ground for abortion, coming down to 10 deaths to 100,000 live births for countries where abortion is allowed for fetal impairment, and as low as 0 and 1 for countries in categories 4 and 5 where abortion is allowed for economic or social reasons and on request, respectively.

The main reason why the unsafe abortion rate and mortality ratio only begin to fall substantially, under laws in categories 4 to 6, is probably that most women’s reasons for abortion also fall into those categories. Thus, most abortions become safe mainly or only where women’s reasons for abortion, and the legal grounds for abortion coincide, that is to say, not only to protect the woman’s health and life, and on grounds of fetal impairment, but also for socio-economic reasons and, most importantly, at the woman’s request.

There are a number of caveats worth mentioning with regard to these data. First, because of the difficulty of gathering data on unsafe abortions where abortion is highly restricted, the available information is not completely reliable. However, non-reporting or under-reporting would tend to reinforce the patterns shown in Figures 1 and 2, rather than diminish them. Data from countries are gathered from a variety of sources, including hospital records and survey data. Although there may be considerable unevenness in the quality and coverage of the data across countries, under-reporting is nevertheless much more likely than over-reporting and would not significantly change the patterns illustrated.

Second, what a law says on paper is not necessarily reflected in its implementation by health services. For example, there are countries where abortion to preserve the woman’s physical and mental health is interpreted broadly by health professionals, thus allowing many women access to safe abortion services. This may be why such countries have a low incidence of unsafe abortion and low mortality. Moreover, in countries where abortion is highly restricted, the standard of overall health care ranges from high to poor. It can be presumed that at least some women in these countries (those who can afford it) have access to safe, albeit illegal, abortion services.

Conversely, even where the letter of the law is enabling (categories 5 and 6), good quality services may not be widely available or accessible, or the skills of providers and the methods they use may be inadequate, outmoded or unsafe. This would explain why unsafe abortion rates and mortality ratios may remain much higher than zero in such countries. In fact, countries in any of the six categories that have a high mortality ratio due to unsafe abortion are likely to be those with the least effective and accessible health care services, making complications and deaths from unsafe abortion more likely.

In spite of these caveats, however, the data in both figures clearly indicate that legislation that allows abortion on broad grounds is associated with a lower incidence of unsafe abortion and much lower mortality from unsafe abortion, as compared to legislation that greatly restricts abortion.

The parameters of change

In the decade since the ICPD Programme of Action was approved and the Millennium Development Goals were written, a number of countries have successfully legalised abortion on broad grounds and begun training providers, thereby making abortion and abortion services safer for women. In other countries, less restrictive laws than in the past are being proposed or have already been passed. In still others, bills in national parliaments to legalise abortion may have been lost by as little as only one vote. In addition, ten years of post-abortion care for the complications of unsafe abortion may finally be showing results. Also important is the fact that in many legally restricted settings, there seem to be fewer deaths and far fewer serious complications where women are using medical abortion in sufficient numbers, a trend for which evidence was first collected more than ten years ago.Citation8 Overall, these trends spell actual and potential positive public health consequences for women, and it important to ensure that they continue.

A wide range of actions have formed part of national campaigns for safe, legal abortion over the past century. These encompass abortion law reform, provision of safe services, regulation of quality of care, inclusion of training in medical curricula for physicians and mid-level providers, and provision of information and support to women — all of which involve stakeholders from many areas of expertise.

In most countries where restrictive abortion laws have been successfully challenged and changed, broad-based national and local coalitions have been formed that include women’s health activists and advocates, obstetrician—gynaecologists and other physicians, nurses, midwives and other health care providers, health service managers, medical researchers and statisticians, social scientists, family planning providers, lawyers, judges, policymakers, parliamentarians, governmental and intergovernmental agencies and officials, health economists, journalists, community leaders, trade unionists, women and women’s groups at grassroots level, not to mention artists, novelists and filmmakers.

Step by painful step, those who believe women should not have to suffer and die because a pregnancy is unwanted find themselves working together to “…affect public awareness and opinion, gradually wearing away entrenched traditional views of abortion.”Citation9

Sometimes this work begins with only a handful of people. It may sometimes take a decade or more before a critical mass is reached, or when a paradigmatic event comes to public attention, when change is more likely to take place. Indeed, there are many instances where it has taken 30—40 years of campaigning before a good law is finally in place and still another decade to implement it fully. Hopefully, this amount of time will not be as necessary in future as more countries come to accept the benefits of making abortion safe.

Women who have had abortions and women’s health activists who tell their stories can give abortion a human face through the media and publications, drama and role play, and in public meetings. Personal stories, not just data, help to make the consequences of unsafe abortion impossible to ignore. Prominent women have spoken out in many countries (Alexandra Kollontai in former Soviet Russia and Simone de Beauvoir in France are just two examples) but the key to success is to involve women at grassroots level, health care providers and their professional associations, and policymakers, as the surest way to achieve legal and health system reform.

The public health sector must take responsibility for ensuring the provision of safe abortions, both medical and surgical, while recognising that the private (often non-profit) sector in many countries is compensating for the failure of public health services to do so. Where the public health sector is unable to take up this responsibility, enabling non-profit making clinics to do so is a viable alternative and has worked well in many settings across the globe. Regulation by government of both public and private abortion services has been shown to be necessary in all countries to ensure quality of care, humane treatment, use of the safest methods, and provision of services free or at a cost that even the poorest women can afford. Guidance on best policy and practice, based firmly in evidence and public health principles, was published by the World Health Organization in 2003,Citation10 and should be required reading in all countries.

Although serious complications of unsafe abortion can result in death if not treated in a timely manner, induced abortion is one of the simplest and safest medical procedures known today, so safe that it is no longer necessary for obstetrician—gynaecologists or other physicians to be the main providers in the vast majority of cases. In their place, national policies should allow and ensure training for mid-level providers in the provision of first trimester medical and surgical abortions at primary care level and second trimester medical abortions at secondary level. Training should be a mandatory part of the curriculum and the subject of in-service training for willing providers as well. In spite of the resistance this may generate, this issue must be faced, particularly in countries where there is a shortage of physicians willing or able to provide abortions, which in itself limits access to services.

Dilatation and curettage (D&C) has for many years now been an outmoded method of abortion, and its continued use is responsible for higher than necessary levels of complications in many countries. The fact that use of D&C is still so prevalent in so many developing countriesFootnote* and countries in transition should be seen as a gross failure on the part of the medical profession to practise evidence-based medicine. Campaigns by medical professional associations are long overdue to insist that D&C be replaced by vacuum aspiration. Higher levels of production and wider distribution of vacuum aspiration equipment is also called for, both to help to create and to meet demand.

Medical abortion too, using mifepristone and misoprostol, is safe and effective, and can be provided by mid-levels providers. Now that both drugs are off-patent, they can be manufactured as generic drugs and approved for use by all countries where abortion is legal for any indications.

There is no excuse to provide any abortion procedure without pain relief, though this practice is reported widely as a form of punishment of women for seeking abortion. Campaigns are needed among health professionals to sensitise them as to why women have abortions, and to expose and denounce unacceptably cruel and punitive behaviour, including towards women who are in hospital for complications of unsafe abortions.Citation12 Campaigns among health professionals are also needed to reduce the stigma of providing abortion, and to recruit those who are sympathetic to women’s need for abortion to train as providers and to make abortion provision an acceptable career path.

More attention needs to be given to second trimester abortions, which may be particularly unsafe in legally restricted settings and a neglected and invisible cause of maternal mortality.Citation13 Making first trimester abortion on request legal is an important step forward, but this does not obviate the need for safe second trimester abortions, not only on grounds of fetal impairment but also for those women, usually among the most vulnerable, who have been unable to access abortion any earlier.

Women’s reasons for abortion are intimately bound up with their lives, even if others do not find their reasons totally acceptable. For example, sex selective abortion of female fetuses is a consequence of the low status of women in society, exacerbated by population policies which limit family size. It cannot be legislated away through restrictions on abortion, let alone on the use of amniocentesis, ultrasound or other technology that permits identification of fetal sex. Sex selection as a form of discrimination against girls will only disappear when girl children and women are as highly valued and welcomed in families and in society as boy children and men.Citation14, Citation15

In all developing country regions, adolescent girls and young women are high on the list of those having unsafe abortions, often with little or no access to contraception before or after an unwanted pregnancy.

As part of safe motherhood information campaigns on the danger signs of complications following pregnancy and birth, information on the danger signs of abortion complications and where to seek help should be included.

The media can be a highly negative or highly positive force in campaigns for safe, legal abortion. It is crucial to bring journalists and the media on board, and to sensitise and involve them in national action for safe abortion.

Last but not least, NGOs, governments and intergovernmental agencies should actively seek to replace any form of donor funding or economic aid that censors or forbids them to work for, advocate or provide safe, legal abortions—as a violation of their public health goals, their democratic rights and their autonomy, not to mention their support for women’s rights.

Future perspectives

It is the rare woman indeed who can say that abortion has never touched her life. It is time to break the silence in many more countries and to stop apologising for abortion. Safe abortion is an essential health service for women, as essential for sexual and reproductive health as safe contraception, safe pregnancy and delivery care, freedom from coercion and violence in sexual relationships and access to the means to practise safer sex.

“…Until having an abortion is considered as acceptable morally as using contraception, women will not have gained their full reproductive rights.” Citation16

The vast majority of women who seek abortions are either already mothers or not ready to become mothers. Some cannot afford to support another child; others have had pregnancy forced on them. Some cannot carry the burden arising from fetal anomalies; others do not wish to be mothers at all. Every woman who seeks an abortion does so because for her it is necessary. Whatever her reasons, it is her body and her life, and her decision must be respected.

“A year later, I can say with certainty that I made the right decision. I have suffered no sorrow, no guilt, no pain … only relief that I was able to correct a mistake that would have altered my life forever… Was the embryo inside me life in some form? Yes, of course. Was it the equivalent of an adult life such that its rights should have exceeded mine? No. Do I believe that I committed murder? No. Do I regret it? Am I sorry? No.” Citation17

This paper clearly shows that where legislation allows abortion on broad indications, there is a lower incidence of unsafe abortion and much lower mortality from unsafe abortions, as compared to legislation that greatly restricts abortion. This is a compelling public health argument for making abortion legal on the broadest possible grounds. The value of abortion law reform to protect and save women’s lives is incontrovertible. In spite of sometimes powerful opposition and terrible setbacks, the public health imperative is gaining ground in many parts of the globe.

Acknowledgements

I am indebted to everyone who reviewed and provided advice and information for this paper, as well as to all the authors whose papers follow my own in this publication.

Notes

* Unsafe abortion is defined as “a procedure for terminating an unwanted pregnancy either by persons lacking the necessary skills or in an environment lacking the minimal medical standards, or both”.Citation2

* In India, for example, D&C is still being used for 89% of abortions and as a “check” following vacuum aspiration procedures, according to a recent study in six states.Citation11

References

- World Health Organization. Unsafe Abortion: Global and Regional Estimates of the Incidence of Unsafe Abortion and Associated Mortality in 2000. 2004; WHO: GenevaFull references available at: http://www.who.int/reproductive-health/publications/unsafe_abortion_estimates_04/estimates.pdf

- World Health Organization. The Prevention and Management of Unsafe Abortion. Report of a Technical Working Group. 1992; WHO: Geneva.

- W Cates. The first decade of legal abortion in the United States: effects on maternal health. J Douglas Butler, DF Walbert. Abortion, Medicine and the Law. 1986; Facts on File Publications: New York, 307–321.

- BR Johnson, M Horga, P Fajans. A strategic assessment of abortion and contraception in Romania Reproductive Health Matters. 12(24 Suppl.): 2004; 184–194.

- Reproductive Rights Alliance. Five year review of the implementation of the Choice on Termination of Pregnancy Act 92 of 1996. 2002; Progress Press: JohannesburgCited in: Cooper D, et al. Ten years of democracy in South Africa: documenting transformation in reproductive health policy and status. Reproductive Health Matters 2004;12(24):70—85

- United Nations Population Division. World Population Prospects 2002. Document POP/DB/WPP/Rev.2002/4/F1. 2003; UN: New York.

- United National Population Division. World Abortion Policies 1999. 1999; UN: New York(Wall chart)

- SH Costa, MP Vessy. Misoprostol and illegal abortion in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil Lancet. 341: 1993; 1258–1261.

- G Shakya, S Kishore, C Bird. Abortion law reform in Nepal: women’s right to life and health Reproductive Health Matters. 12(24 Suppl.): 2004; 75–84.

- World Health Organization. Safe Abortion: Technical and Policy Guidance for Health Systems. 2003; WHO: Geneva.

- R Duggal, S Barge. Abortion Services in India: A Situational Analysis. Abortion Assessment Project — India. 2004; CEHAT and HealthWatch: MumbaiReported in: Duggal R, Ramachandran V. The Abortion Assessment Project — India: key findings and recommendations. Reproductive Health Matters 2004;12(24 Suppl.):122—29

- C Steele, S Chiarotti. With everything exposed: cruelty in post-abortion care in Rosario, Argentina Reproductive Health Matters. 12(24 Suppl.): 2004; 39–46.

- D Walker, L Campero, H Espinoza. Deaths from complications of unsafe abortion: misclassified second trimester deaths Reproductive Health Matters. 12(24 Suppl.): 2004; 27–38.

- M Kishwar. Abortion of female fetuses: is legislation the answer? Reproductive Health Matters. 1(2): 1993; 113–115.

- P Löfstedt, S Luo, A Johannson. Abortion patterns and reported sex ratios at birth in rural Yunnan, China Reproductive Health Matters. 12(24): 2004; 86–95.

- M Løkeland. Abortion: the legal right has been won, but not the moral right Reproductive Health Matters. 12(24 Suppl.): 2004; 167–173.

- At: www.imnotsorry.com. Accessed 12 January 2005.