Abstract

Complications of unsafe abortion contribute to high maternal mortality and morbidity in Mozambique. In 2002, the Ministry of Health conducted an assessment of abortion services in the public health sector to inform efforts to make abortion safer. This paper reports on interviews with 461 women receiving treatment for abortion-related complications in 37 public hospitals and four health centres in the ten provinces of Mozambique. One head of both uterine evacuation and contraceptive services at each facility was also interviewed, and 128 providers were interviewed on abortion training and attitudes. Women reported lengthy waiting times from arrival to treatment, far longer than heads of uterine evacuation services reported. Similarly, fewer women reported being offered pain medication than head staff members thought was usual. Less than half the women said they received follow-up care information, and only 27% of women wanting to avoid pregnancy said they had received a contraceptive method. Clinical procedures such as universal precautions to prevent infection were less than adequate, in-service training was less than comprehensive in most cases, and few facilities reviewed major complications or deaths. Use of dilatation and curettage was far more common than medical or aspiration abortion methods. Current efforts by the Ministry to improve abortion care services have focused on training of providers in all these matters and integration of contraceptive provision into post-abortion care.

Résumé

Les complications des avortementsàrisque contribuent au taux élevé de mortalité et morbidité maternelles au Mozambique. En 2002, le Ministère de la santé a évalué les services d’avortement dans le secteur public. Il a interrogé 461 femmes traitées pour des complications de l’avortement dans 37 hÁpitaux publics et 4 centres de santé dans les 10 provinces du Mozambique, ainsi que le chef des services d’évacuation utérine et de contraception de chaque centre ; 128 prestataires ont également été interrogés sur la formation et les attitudesàl’égard de l’avortement. Les femmes ont déclaré avoir attendu longtemps avant d’Átre traitées, plus longtemps que ne l’ont indiqué les chefs des services d’évacuation utérine. De mÁme, le nombre de femmes disant qu’on leur avait proposé des antalgiques était inférieuràla proportion jugée habituelle par les chefs de service. Moins de la moitié des femmes ont signalé avoir reçu des informations sur les soins post-avortement, et seulement 27% des femmes voulant éviter une grossesse ont déclaré avoir reçu une méthode contraceptive. Les procédures cliniques telles que les précautions d’hygiène étaient inadéquates, la formation en cours d’emploi était loin d’Átre complète, et peu de centres examinaient les raisons des complications majeures ou des décès. L’emploi de la dilatation et du curetage était beaucoup plus fréquent que les méthodes d’avortement médicamenteux ou par aspiration. Les efforts du Ministère pour améliorer les services d’avortement se sont centrés sur la formation des praticiens dans tous ces domaines et l’intégration de la contraception dans les soins après avortement.

Resumen

El aborto inseguro contribuye a las altas tasas de morbimortalidad materna en Mozambique. En 2002, el Ministerio de Salud evaluó los servicios de aborto del sector público para relatar los esfuerzos por hacer el aborto más seguro. En este artáculo se informa de las entrevistas con 461 mujeres atendidas por complicaciones del aborto en 37 hospitales públicos y cuatro centros de salud en diez provincias de Mozambique. En cada establecimiento se entrevistó al jefe de los servicios de evacuación endouterina y al de los servicios de anticoncepción, asá como a 128 proveedores respecto a la capacitación y las actitudes hacia el aborto. Según las mujeres, el tiempo de espera desde su llegada hasta el tratamiento fue mucho más largo que lo que informaron los jefes del servicio de evacuación endouterina. Menos mujeres informaron haber sido ofrecidas medicamentos para el dolor que lo que los jefes consideran normal. Menos de la mitad dijo que recibió información sobre los cuidados de seguimiento; sólo el 27% de las que deseaban evitar un embarazo informaron que habáan recibido un método anticonceptivo. Los procedimientos clánicos eran deficientes; por lo general, la capacitación en servicio no era exhaustiva; y en pocos establecimientos se revisaban las complicaciones mayores o las muertes. El aborto por legrado uterino instrumental era mucho más común que el aborto con medicamentos o por aspiración. Los esfuerzos actuales del ministerio por mejorar los servicios de aborto se centran en capacitar a los proveedores en estos aspectos y en integrar el suministro de anticonceptivos a la atención postaborto.

The maternal mortality ratio in Mozambique, estimated at 1,000 deaths to 100,000 live births, is one of the highest in the world.Citation1 Approximately one in seven women dies during pregnancy. This high mortality can be attributed to several inter-related factors. Modern contraceptive use is low, only 5% of married women. Women often start childbearing at a young age and have a high fertility rate of 5.2. In addition, years of civil war and poverty have led to a limited health care system with a scarcity of trained health providers, especially in rural areas.Citation2 Lastly, maternal mortality and morbidity are often the result of unsafe abortion.

Induced abortion in Mozambique currently has a quasi-legal status.Citation3 Although the criminal code calls for imprisonment for the provision or procurement of abortion unless the woman’s health or life is at risk,Citation4 a 1981 Ministry of Health (MOH) decree supported a broad interpretation of this risk, and abortion has been available upon request in several public hospitals ever since.Citation3 Most abortions performed in these public hospitals are conducted by maternal and child health (MCH) nurses, using misoprostol followed by manual vacuum aspiration 24 hours later.Citation5 Unsafe abortion and resulting complications remain prevalent, however.Citation6, Citation7 A 1995 study conducted in Maputo Central Hospital found that women attending for complications of abortions obtained outside the hospital were younger, living in poorer socio-economic conditions, and more likely to be pregnant for the first time than those attending for an abortion within the hospital setting.Citation8 Among those seeking post-abortion care for complications in the same hospital, 80% cited lack of knowledge of the availability of hospital-based abortion.Citation9 Women also described restrictions regarding pregnancies greater than 12 weeks and fear of lack of confidentiality as reasons not to seek a safe abortion at a hospital. Some facilities attempt to protect providers by requiring excessive documentation from both the woman and a “responsible male”. Finally, women are charged about US$15 for induced abortion in a hospital setting,Citation5 a substantial amount given that approximately 78% of the population live on less than US$2 a day.Citation10

In 2002, the MOH conducted a comprehensive baseline assessment of abortion care services in the public health sector, with technical and financial assistance from Ipas, in order to inform efforts to reduce maternal morbidity and mortality. The objective was to document the strengths and deficiencies of post-abortion care, in order to design appropriate interventions to improve women’s health.

Methods

The national health service in Mozambique is organised into four levels: 1) health centres and clinics; 2) district, general and rural hospitals; 3) provincial hospitals and 4) central and specialised hospitals. This baseline assessment included all the public hospitals in the country (n=39) and six local health centres situated in Nampala and Maputo provinces, where the MOH planned to initiate interventions. After excluding two hospitals and two health centres that did not perform uterine evacuation at the time of the study, the study sample included 41 facilities: 4 health centres; 27 district, general, or rural hospitals; 7 provincial hospitals and 3 central hospitals.

Data were collected from July 2002 to January 2003. We conducted interviews, using mostly close-ended questionnaires, with four types of respondents at each study facility: 1) a convenience sample of 10 consecutive patients who received uterine evacuation for abortion-related complications, 2) the head of uterine evacuation services, 3) the head of contraceptive services and 4) one to five providers who perform uterine evacuation.

We conducted exit interviews with 461 patients (9—13 women at each facility) who received uterine evacuation for abortion-related complications. The interviews were conducted in a private area by one or two nurses from each facility who were not involved with post-abortion care and who had been trained by the study coordinator, a public health nurse-midwife. Women who had had any method of uterine evacuation, including manual or electric vacuum aspiration or dilatation and curettage for abortion-related complications, were eligible to participate. Participation was not restricted based on number of weeks of pregnancy prior to abortion or type of abortion (spontaneous or induced, safe or unsafe). Exit interview data are missing from three hospitals. We did not collect data on the response rate.

The exit questionnaire was translated into Portuguese and then back into English by two people working independently, to ensure accuracy. The questionnaire covered demographic characteristics, waiting time for treatment, treatment information, follow-up care information, privacy, pain management, contraception and satisfaction with services. Women were asked if they received information on seven main warning signs indicating the need for immediate medical care: bleeding for more than two weeks; bleeding more than normal menstruation; strong increase in odour; fever; cold shivers or feeling unwell; and fainting or vaginal discharge with odour. No data were collected on the type of abortion or details of the type of abortion complications. The type of pain medication and uterine evacuation method were also not recorded. Prior to discharge, potential participants were read a standardised consent form, which specified that participation was completely voluntary and would not affect current or future health care. Participants gave verbal informed consent prior to answering the questionnaire.

Using standardised data collection forms, 18 trained physicians and MCH nurses interviewed the head of both the uterine evacuation and contraceptive services from each facility. The uterine evacuation questionnaires covered six topics: general facility information; clinical services for abortion; characteristics of women requiring uterine evacuation; abortion equipment, supplies and treatment area; and staff training. The contraceptive questionnaire collected information about the frequency of contraceptive provision, including method types, and counselling. Finally, an interviewer also administered a short questionnaire to one to five providers who performed uterine evacuation at each study facility about their training and attitudes toward abortion care.

Data were entered into Epi-Info 2000 and imported into SAS version 8.01 for analysis. We used a paired t- test to compare each woman’s reported waiting time from arrival to treatment with the time estimated by the provider interviewed at that same facility. We could not directly compare the waiting times from treatment to discharge since the provider questions were disaggregated by uterine evacuation type, and the patient questionnaires did not include questions about uterine evacuation method. Using logistic regression, we calculated odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) to assess the relationship between women’s characteristics and measures of service delivery quality. Specifically, we were interested in assessing whether women’s abortion care experiences differed according to adolescent status (<20 years of age versus older); prior history of abortion (no prior abortion versus at least one reported); or poverty (potable water and electricity in house versus lacking either or both).

Results

Characteristics of respondents

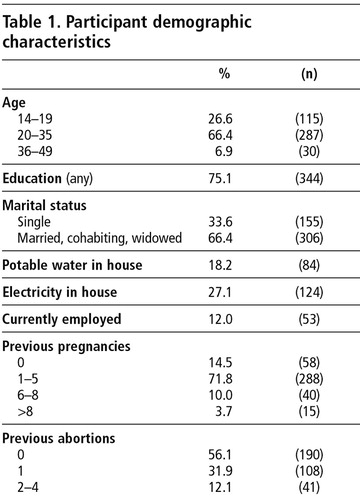

Women were a mean age of 24.4 years (range 14—49). About 27% were adolescents (ages 14—19). Most were married, cohabitating or widowed (66%) and had had at least one prior pregnancy (86%) ( ). About 86% were poor, which we defined as not having either potable water or electricity in their residence. Among the 44% of women who had had a previous abortion, they reported a mean of 1.4 abortions prior to the current one (range 1—4). About 36% of the adolescents reported at least one prior abortion.

Both the uterine evacuation and the contraceptive services questionnaires were completed by one head staff member at each of the 41 facilities. Obstetrician—gynaecologists, general practitioners and surgical technicians primarily completed the former while MCH nurses answered the latter. Interviews were conducted in the obstetrics department (55%), gynaecology department (13%) and outpatient clinic or procedure room (32%). The abortion training and attitudes questionnaire was completed by 128 providers (one to five at each facility) at 35 study facilities. Most (77%) were mid-level providers (i.e. midwives, surgical technicians or nurses); the remainder were general practitioners (17%), post-graduates (2%) or obstetrician—gynaecologists (3%).

Waiting time

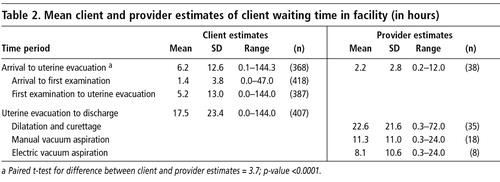

Although both women and heads of uterine evacuation services reported lengthy waits for examination, treatment and discharge, women generally reported longer waits ( ). The mean waiting time from arrival to treatment reported by women was 3.7 hours longer than that reported by providers, which is a statistically significant difference (p<0.0001). Women reported a mean wait of 17.5 hours from treatment to discharge. Head staff members were asked to estimate the waiting times from treatment to discharge for specific types of uterine evacuation. These mean times ranged from 8.1 hours following electric vacuum aspiration to 22.6 hours following dilatation and curettage.

Treatment and follow-up care information

Only 21% of women reported that the attending provider introduced him or herself, and few women (16%) were given the option of being accompanied by a friend or relative during the procedure. While most women (83%) reported being asked about their medical history, only one-half reported being informed of their diagnosis. Only 22% reported having the opportunity to ask questions about the procedure before it was performed. Just over half stated that they received information about the uterine evacuation procedure beforehand (52%) or were given information about whether treatment was successful (54%).

A minority of women reported receiving a follow-up appointment (30%) or information about follow-up care at home (42%). Specifically, 41% were advised to avoid sexual activity until cessation of bleeding, and 12% were informed about the expected timing of resumption of menstruation. Only 42% affirmed that they were warned of the risk of repeat pregnancy before the resumption of menses unless an effective contraceptive method was used. Over half of the women (53%) said they were not informed of any of the seven main warning signs of the need for immediate medical care, while 13% were advised of all of them.

Almost all head staff members reported that their facility had no information or educational materials (e.g. posters, brochures, counselling cards, flip charts) on post-abortion care; only one provider reported the use of post-abortion care information sheets.

Privacy

While most women reported sufficient privacy while changing their clothes (81%), giving their medical history (81%), being examined (90%), and undergoing treatment (89%), less than half (49%) reported adequate privacy during discussions regarding contraception. In contrast, the heads of uterine evacuation services in the 38 facilities with patient interview data had more concerns about lack of privacy than the women did. A substantial proportion of providers rated the visual and auditory privacy of the examination room (42% and 31%, respectively) and the procedure room (58% and 42%, respectively) as poor.

Pain management

Thirty-four per cent of women reported no or light pain while waiting for treatment, 20% reported moderate pain and 46% intense pain. As regards pain during the evacuation procedure, 35% reported no or light pain while 24% reported moderate and 41% intense pain. Only 40% of women said the provider offered something for pain control prior to the procedure, and poor women were less likely to report being offered pain medication (OR 0.6; 95% CI 0.4, 1.0) than others. About 28% reported that they had received pain medication for the procedure; reports of receiving pain medication did not differ by patient characteristics. About 19% of those receiving pain medication reported that the amount was insufficient.

Conversely, 61% of providers in the 38 facilities with exit data reported that patients having manual vacuum aspiration typically received pain control medication, most frequently in the form of non-narcotic analgesics (26%) or light sedation (17%). A similar proportion (62%) reported that patients having dilatation and curettage usually received medication for pain. General anaesthesia (30%) and non-narcotic analgesics (16%) were cited as the methods most often used during dilatation and curettage. No data were collected on dosage, providers’ reasons for not offering or giving medication, or whether women sometimes requested additional medication.

Clinical procedures and equipment

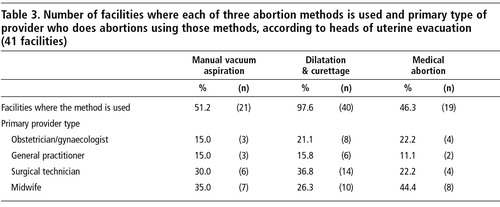

The heads of uterine evacuation services were asked which of three abortion methods were used in the facility: manual vacuum aspiration, medical abortion, or dilatation and curettage. They were also asked to identify the cadre of provider that was primarily responsible for abortions using each of the three methods ( ). While most heads of uterine evacuation services (98%) in the 41 study facilities reported that dilatation and curettage was performed, fewer reported the use of manual or electric vacuum aspiration or medical abortion (51%, 20% and 46%, respectively) in their facility. Few head staff (10%) said that their facility had written guidelines and protocols for treatment of abortion complications. Less than half (49%) stated that they had a systematic process for reviewing major abortion-related complications, including deaths. However, among those with a review process, 25% reported that the process was rarely used.

One respondent (2%) said that their facility recommended the presence and consent of parents or other relatives when treating incomplete abortion in adolescents. The remainder reported that their procedures for treating adolescents were similar to those for adults.

Among the head staff in the 21 facilities that performed manual vacuum aspiration, most (86%) reported that the re-usable instruments (i.e. cannulae, speculae, tenaculum and forceps) were sterilised after every use. However, only 56% of those who reported routine decontamination said that they subsequently used high-level disinfection for the cannulae, and 29% of providers said that the person responsible for decontamination and high-level disinfection did not have adequate training in these procedures.

Contraceptive provision

Most women (74%) said that they did not want another pregnancy in the near future. Adolescents were half as likely to report pregnancy desire as their older counterparts (OR 0.5; 95% CI 0.3, 0.9). Of the women who did not want to become pregnant, less than half were given contraception information (49%), had a method suggested to them (39%) or were asked about their choice of method (37%). Of those who were asked about choice of method (n=123), most wanted oral (45%) or injectable contraception (37%). Only 27% of those who did not want to become pregnant received a method, of whom 55% were given oral contraception and 33% received injectable contraception. Seven per cent of women received male condoms. Ten per cent of the women receiving contraception were not given their chosen method.

Seventy-six per cent of heads of contraceptive services from the 38 facilities with patient exit data reported that women presenting with incomplete abortion received contraceptive counselling after the evacuation procedure, and 31% of head staff members reported that contraceptive methods were always or frequently supplied to these women.

Providers reported that the following contraceptive methods were available at their facility: combined oral contraceptives (79%), progestogen-only contraceptives (79%), injectable contraceptives (79%), condoms (61%), intrauterine devices (61%) and spermicide (3%). No implants or diaphragms were available. Most providers (83%) reported that the facility had a mechanism for referring women with incomplete abortion to contraceptive services.

Provider training and attitudes

Thirty-four per cent of the head staff said that their facility had a supervisor in charge of post-abortion care services, of whom 50% were trained in post-abortion contraceptive counselling and 92% in manual vacuum aspiration.

Among the 99 mid-level providers who completed the questionnaire on abortion training and attitudes toward abortion care in 35 of the facilities, 43% reported that they had received in-service training on emergency obstetric care and that the following topics were included in their most recent training: manual vacuum aspiration clinical procedures (15%), communication between abortion patients and staff (23%), aspiration equipment cleaning and maintenance (27%), universal precautions for infection prevention (26%) and post-abortion contraceptive counselling and referral (23%).

The 29 physicians interviewed for this questionnaire reported that they strongly agreed (46%), agreed (46%) or had no opinion (7%) about the use of manual vacuum aspiration by trained mid-level providers. Most providers rated the ease and simplicity of manual vacuum aspiration as very satisfactory or satisfactory (60%), 33% were indifferent or did not know, and 7% described it as very unsatisfactory.

Discussion

The deficiencies in care identified in this study should be used to inform current efforts to improve abortion care services across Mozambique. Since patients at 93% of the facilities that performed uterine evacuation at the time of the study were interviewed, the sample is likely to be representative of those attending public hospitals nationally, though selection bias could have occurred due to the use of a convenience sample with an unknown response rate.

Comparisons between women’s and providers’ responses revealed substantial discordance. Women reported lengthy waits, and statistically significantly longer waits from arrival to treatment than providers did. Shortening patient waiting times is important to reduce the risk of complications worsening, to reduce costs and to ameliorate the pain and emotional burden for women.Citation11, Citation12 The lengthy waits reported by both patients and providers, in general, are consistent with findings from a large exit survey of men and women attending 34 health clinics for any type of health care in Mozambique.Citation13

Although medication for pain management should be offered to all women undergoing uterine evacuation,Citation14 only a minority of women reported being offered or receiving pain medication. A greater proportion of providers said that women were generally given pain medication for manual vacuum aspiration or dilatation and curettage. A recent study in abortion services in one province in South Africa found that in about 26% of cases, pain medication was not given early enough to take effect before the procedure.Citation15 In other studies, providers have failed to offer pain medication due to judgemental attitudes regarding abortion, inadequate training or a lack of supplies.Citation16

Although the World Health Organization (WHO) recommends medical abortion up to 9 completed weeks of pregnancy or vacuum aspiration (manual or electric) up to 12 completed weeks of pregnancy,Citation14 half the facilities did not do medical or aspiration abortions, according to providers. About 37% of facilities used dilatation and curettage only, which is known to contribute to a higher rate of complications and requires longer hospital stays. Training that would allow all facilities to use the preferred methods was inadequate at the time of the study, according to the reports of mid-level providers.

Differences between the responses of heads of services and patients underscore the importance of including patient interviews in future assessments of abortion care services. In general, relying only on data from providers could result in substantial under-estimates of the effects of an intervention since any initial deficiencies could be minimised or missed. However, discrepancies in responses could have occurred because, for example, the heads of uterine evacuation services were not aware of waiting times, and reception staff might have given more accurate estimates. Thus, a variety of sources, patients and different cadres of provider and staff, and interviews as well as direct observations, might be needed to get an accurate picture of service quality.

Warning signs of the need for immediate medical care were not conveyed effectively. Futhermore, high quality care requires that women receive information about their condition and the treatment protocol.Citation14, Citation17

Although WHO guidance for safe abortion specifies that women should also receive information on contraception post-abortionCitation14 and research has shown the effectiveness of ward-based contraceptive services in reducing unplanned pregnancies,Citation18 low rates of contraceptive information and method provision were found. While social norms might have led to under-reporting of previous abortions, a high proportion of women in fact reported previous abortions, including 36% of adolescents. This is consistent with the high rate of unsafe abortions among adolescents in Africa in general,Citation19 whose access to contraception is known to be especially low.

A substantial proportion (10%) of women receiving contraception were not given their chosen method, a shortcoming which can lead to higher rates of discontinuation.Citation20 Some providers reported a preference for combined oral contraceptive use during the first month post-abortion, in the belief that it promotes recovery of the endometrial lining. In some cases, stock shortages might exist. Whatever the reasons, an important opportunity for contraceptive counselling and method provision to prevent another unwanted pregnancy was lost. Women undergoing abortion in Mozambique have been shown to have high STI rates,Citation21 yet few women reported receiving condoms. Post-abortion contraceptive counselling should also include condom promotion for contraception and to prevent HIV and STIs.

This baseline assessment was undertaken prior to the initiation of an MOH intervention to provide training in post-abortion care and manual vacuum aspiration instrument distribution, to improve post-abortion care services in the public health sector. Master trainers were prepared to train other providers in the full range of post-abortion care elements required for quality care (including pain management, counselling and contraceptive provision). Several programme managers also visited health facilities in Nairobi, Kenya, in order to learn how contraceptive services can be better integrated into post-abortion care.

Medical school curricula for physicians and MCH nurses throughout the nation now include training in the use of misoprostol for medical abortion and manual vacuum aspiration, instead of dilatation and curettage. Furthermore, MCH nurses today are trained in holistic post-abortion care, either in pre-service education or in in-service trainings. At the facility level, post-abortion care services should be organised on an outpatient basis using manual vacuum aspiration, to reduce waiting times.Citation12 Shortages of contraceptive commodities and pain medication should be addressed. At the same time, privacy of contraceptive counselling needs to be ensured.

Finally, the MOH should clarify its own policy of allowing abortions in public health facilities through written guidelines on norms and practices. This would allow the MOH to monitor the quality of abortion care in health facilities and reduce barriers to safe abortion in Mozambique, which should in turn reduce the country’s high rates of abortion-related morbidity and mortality.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Janie Benson, Ellen Mitchell and Charlotte Hord Smith of Ipas for their review of the manuscript. We are grateful to Drs Leonardo Chavane, Ercilia de Almeida and Della Mercedes for their active role in collecting the data, as well as the nurses who conducted the exit interviews. Finally, we thank all the women and providers who participated in the research.

References

- World Health Organization. The World Health Report: Change History 2004. 2004; WHO: Geneva.

- J Cliff, AR Noormahomed. The impact of war on children’s health in Mozambique Social Science and Medicine. 36: 1993; 843–848.

- V Agadjanian. “Quasi-legal” abortion services in a sub-Saharan setting: users’ profile and motivations International Family Planning Perspectives. 24: 1998; 111–116.

- M Goçalves. Portuguese Criminal Code, with annotation and commentary. 1972; Editora Almadina: Coimbra.

- Limbombo A, Ustá MB. Mozambique abortion situation: country report. Expanding access: midlevel providers in menstrual regulation and elective abortion care. IHCAR-Ipas conference report. Johannesburg, December 2001.

- AC Granja, F Machungo, A Gomes. Adolescent maternal mortality in Mozambique Journal of Adolescent Health. 28: 2001; 303–306.

- L Jamisse, F Songane, A Libombo. Reducing maternal mortality in Mozambique: challenges, failures, successes and lessons learned International Journal of Gynecology and Obstetrics. 85: 2004; 203–212.

- E Hardy, A Faúndes, A Bugalho. Comparison of women having clandestine and hospital abortions: Maputo, Mozambique Reproductive Health Matters. 5(9): 1997; 108–115.

- F Machungo, G Zanconato, S Bergström. Reproductive characteristics and post-abortion health consequences in women undergoing illegal and legal abortion in Maputo Social Science and Medicine. 45: 1997; 1607–1613.

- United Nations Development Programme. Human Development Report 2003: Millennium Development Goals: a compact among nations to end human poverty. 2003; UNDP: New York.

- J Benson, V Huapaya, M Abernathy. Improving quality and lowering costs in an integrated postabortion care model in Peru. 1998; Population Council: New York.

- BR Johnson, J Benson, J Bradley. Costs and resource utilization for the treatment of incomplete abortion in Kenya and Mexico Social Science and Medicine. 36: 1993; 1443–1453.

- RD Newman, S Gloyd, JM Nyangezi. Satisfaction with outpatient health care services in Manica Province, Mozambique Health Policy and Planning. 13: 1998; 174–180.

- World Health Organization. Safe Abortion: Technical and Policy Guidance for Health Systems. 2003; WHO: Geneva.

- EMH Mitchell, K Mwaba, MS Makoala. A Facility Assessment of Termination of Pregnancy (TOP) Services in Limpopo Province, South Africa. 2004; Ipas: Chapel Hill.

- J Solo. Easing the pain: pain management in the treatment of incomplete abortion Reproductive Health Matters. 8: 2000; 45–51.

- J Bruce. Fundamental Elements of the Quality of Care: A Simple Framework. Working Paper No.1. 1989; Population Council: New York.

- BR Johnson, S Ndhlovu, SL Farr. Reducing unplanned pregnancy and abortion in Zimbabwe through postabortion contraception Studies in Family Planning. 33: 2002; 195–202.

- World Health Organization. Unsafe Abortion: Global and Regional Estimates of the Incidence of Unsafe Abortion and Associated Mortality in 2000. 4th ed, 2004; WHO: Geneva.

- PT Piotrow. Counseling for better contraception Integration. 1993; 26–31.

- F Machungo, G Zanconato, K Persson. Syphilis, gonorrhoea and chlamydial infection among women undergoing legal or illegal abortion in Maputo International Journal of STD & AIDS. 13: 2002; 326–330.