Abstract

Increasing the proportion of deliveries with skilled attendance is widely regarded as key to reducing maternal mortality and morbidity in developing countries. The percentage of deliveries with a health professional is commonly used to assess skilled attendance, but measures only the presence of an attendant, not the skills used or the enabling environment. To supplement currently available information on the presence of an attendant at delivery, a method to measure the extent of skilled attendance at delivery through use of clinical records was devised. Data were collected from 416 delivery records in hospitals, government health centres and private non-hospital maternity facilities servicing Kintampo District, Ghana, using a case extraction form. Based on the defined criteria, summary measures of skilled attendance were calculated. Between 32.6% and 93.0% of the criteria for skilled attendance were met in the sample, with a mean of 65.5%. No delivery met all the criteria. A Skilled Attendance Index (SAI) was developed as a composite measure of delivery care. The SAI revealed that 26.9% of delivery records met at least three-quarters of the criteria for skilled attendance. Documentation of haemoglobin, current pregnancy complications, post-partum vital signs and completed partographs were amongst the criteria most poorly recorded. The purpose of applying these measures should be seen not as an end in itself but to advance improvements in delivery care.

Résumé

Accroı̂tre la proportion d'accouchements pratiqués par un personnel qualifié est considéré comme une mesure essentielle pour réduire la mortalité et la morbidité maternelles dans les pays en développement. Le pourcentage d'accouchements pratiqués par un professionnel de la santé est habituellement utilisé pour évaluer la présence d'un personnel qualifié, mais il ne mesure que la présence d'un personnel, et non les compétences utilisées ou l'environnement habilitant. Pour compléter l'information disponible, on a mis au point une méthode pour mesurer l'étendue des prestations assurées en utilisant les dossiers cliniques. Les données ont été recueillies à partir de 416 dossiers d'accouchements dans des hôpitaux, des centres de santé gouvernementaux et des maternités privées non hospitalières du district de Kintampo, Ghana, en utilisant un formulaire d'extraction de cas. Selon les critères définis, des mesures évaluant l'activité du personnel qualifié ont été calculées. De 32,6% à 93,0% des critères définis étaient présents dans l'échantillon, avec une moyenne de 65,5%. Aucun accouchement ne réunissait tous les critères. Un indice d'assistance par un personnel qualifié a été élaboré comme mesure composite des soins obstétriques. L'indice a révélé que 26,9% des dossiers d'accouchements réunissaient au moins les trois quarts des critères de l'assistance par un personnel qualifié. La vérification de l'hémoglobine, les complications de la grossesse en cours, les signes vitaux post-partum et une surveillance complète au moyen du partographe étaient parmi les critères laissant le plus à désirer. L'application de ces mesures ne devrait pas être considérée comme une fin en elle-même, mais comme un moyen de progresser dans les soins obstétriques.

Resumen

Una forma clave de disminuir la tasa de morbimortalidad materna en los paı́ses en desarrollo es aumentar la proporción de partos que reciben atención especializada. El porcentaje de partos asistidos por un profesional de la salud se utiliza con frecuencia para evaluar la atención especializada, pero mide sólo la presencia de un profesional de la salud en cada parto, y no las habilidades empleadas o el ambiente en que se realiza. Con el fin de complementar la información actualmente disponible sobre la presencia de un profesional de la salud durante el parto, se creó un método para medir el nivel de atención especializada durante el parto mediante la revisión de las historias clı́nicas. Por medio de un formulario de extracción de casos, se recolectaron datos de 416 historias clı́nicas correspondientes a partos atendidos en hospitales, centros de salud gubernamentales y servicios de maternidad particulares extra-hospitalarios que brindan cobertura de atención a la población del Distrito Kintampo en Ghana. Conforme a los criterios definidos, se calcularon las medidas sumarias de la atención especializada prestada. En la muestra se cumplió entre el 32.6% y el 93.0% de los criterios de la atención especializada, con un promedio de un 65.5%. En la atención de ninguno de los partos se cumplió con todos los criterios. Además, se creó un Índice de Atención Especializada como una medida compuesta de la atención obstétrica. Dicho ı́ndice reveló que el 26.9% de las historias clı́nicas obstétricas cumplió por lo menos con tres cuartas partes de los criterios de la atención especializada. Entre los criterios registrados con menor exactitud figuran la documentación de la cifra de hemoglobina, las complicaciones durante el embarazo actual, los signos vitales posparto y el diligenciamiento completo de la ficha obstétrica perinatal. El propósito de aplicar estas medidas debe considerarse no como un fin en sı́ sino como una gestión para fomentar mejorı́as en la calidad de la atención obstétrica.

Increasing the proportion of deliveries with skilled attendance is now being promoted as an important approach to reducing maternal mortality and morbidity in developing countries. This is reflected in the published literature,Citation1 Citation2 international initiativesCitation3 and safe motherhood programmes.Citation4 Current knowledge on the link between skilled attendance and maternal mortality is documented, as well as the limitations of the evidence.Citation5 Skilled attendance is defined as “the process by which a woman is provided with adequate care during labour, delivery and the early post-partum period”.Citation6 This requires a skilled person to attend the delivery and an enabling environment, including adequate supplies, equipment, transport and drugs.

The indicator most commonly used to measure skilled attendance is the percentage of deliveries with a health professional, the information usually being obtained from community-based surveys by asking women to identify the attendant at each of their deliveries over the past three to five years. Much importance is placed on this indicator, and it is currently being used to measure achievement of the international Millennium Development Goal on maternal health.Citation7 Data for this indicator are widely regarded as simple to collect, but the indicator is only a proxy measure of skilled attendance for several reasons. Firstly, only the presence of the health professional is measured, not their skills, and it cannot be assumed that all health professionals are skilled in delivery care.Citation5 Secondly, despite acceptance that skilled attendance incorporates both the attendant and the enabling environment, the proportion of deliveries with a health professional does not reflect the existence of an enabling environment. Finally, international comparisons of this indicator across countries may be flawed, as the inclusion of different types of attendants with different levels of training–doctors, nurses, multi-purpose health workers or maternal and child health workers–varies across countries. Clarification by the World Health Organization that the term “skilled attendant” refers to “people with midwifery skills who have been trained to proficiency in the skills necessary to manage normal deliveries and diagnose or refer obstetric complications”,Citation8 still leaves room for varying interpretations on a country-by-country basis.

To generate new knowledge and methods for measuring skilled attendance at delivery, an international research partnership was formed called SAFE–Skilled Attendance For Everyone.Citation9 This paper describes one SAFE study, the aim of which was to develop a means of measuring skilled attendance that could address some of the limitations of the indicator “percentage of deliveries with a health professional”. The method was to be suitable for routine monitoring purposes by programme managers and clinicians, using health facility data.

Methods

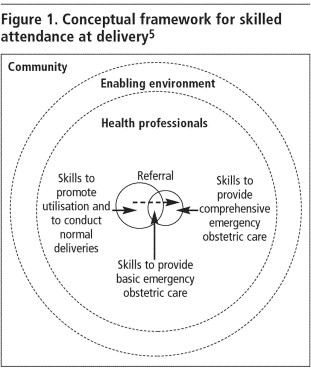

Principles of rapid appraisal influenced method development.Citation10 This is because a means to routinely monitor skilled care in a range of health facilities and within a short time was desired. A schematic framework of skilled attendance at delivery is used as the conceptual basis for determining the components of skilled care.Citation5 In this framework, the demand for delivery by the community is met by the health system, which is equated to the enabling environment for skilled attendance. Drugs, equipment, supplies and transportation are elements of the enabling environment. Although not included in the framework, other features of the health system such as health sector policy or human resource management also comprise or affect the enabling environment. The inner circle represents the health professionals who provide delivery care. The dotted lines indicate that skilled attendance may exist in the community and is not necessarily confined to health facilities. The innermost overlapping circles in the figure represent the different levels of service provision. The arrow indicates referral of complicated cases from basic to comprehensive care.

A list of clinical procedures, interventions and components necessary to provide care for normal and complicated deliveries was developed using standard obstetric texts, the Cochrane Library and World Health Organization publications. Refinements to this list were made by consulting individuals experienced in obstetrics, midwifery and nursing in developing countries. They were asked to review the list and identify items most essential to measuring skilled care at delivery, using and focusing on the skills of the health professionals involved and key aspects of the enabling environment. From this refined list, a series of criteria were identified and reformulated into a case extraction form to collect data from delivery records. The case extraction form was adapted from a study conducted in Ghana and JamaicaCitation11 Citation12 which assessed the quality of emergency obstetric care through criterion-based clinical audit. However, the criteria used in our study on skilled attendance were applicable not only to emergency care, but also to delivery care in normal and complicated cases.

Figure 1 Conceptual framework for skilled attendance at deliveryCitation5

A pilot test of the case extraction form was first completed. A panel of clinicians, programme managers and policymakers from Ghana reviewed the form to ensure congruence with local norms and policies of best practice. Minor alterations to the form were made and these were then tested in delivery units from tertiary to primary level in urban and rural Ghana. Delivery records could be traced in most facilities and sufficient information was available for case extraction.

The main study was conducted in delivery units of Kintampo District from June to August 2001. Eleven health facilities serve Kintampo District. Surveillance data available for the district estimated 3,460 deliveries in the year 2000; 33.0% of these were in health facilities, of which 66.1% occurred in hospitals, 7.1% in government health centres and 26.9% in private non-hospital maternity facilities. Five of the 11 health facilities had less than one delivery per month and were excluded from the study.

Data were retrospectively collected from 416 delivery records, which were selected in proportion to the annual delivery rate of each facility. As there was no information available on existing levels of skilled attendance, the sample size required was based on an equipoise assumption of this being true of 50% of cases. The sample size allowed the resulting estimate of skilled attendance to fall within five percentage points of the true proportion with 90% confidence and accounts for the need for sub-group analysis between normal and complicated deliveries and between different types of health facilities. The sample was selected from the delivery register, identifying the most recent delivery records, until the required sample size was reached in each facility. This was taken as being a random sample as it was likely that the facility deliveries occurred in a way that was representative of facility deliveries in the population as a whole. In hospitals, all delivery records comprised formal clinical case notes bound in a single file, with a standard format for the woman's pregnancy history but unformatted pages for narration of delivery events. In non-hospital health facilities, these formal clinical notes were not available, so nursing notes (usually unformatted), delivery registers and partographs were used. Both formatted and unformatted parts of the delivery records were reviewed to extract data. If a delivery record could not be traced, the next delivery listed in the register was identified and the corresponding record found.

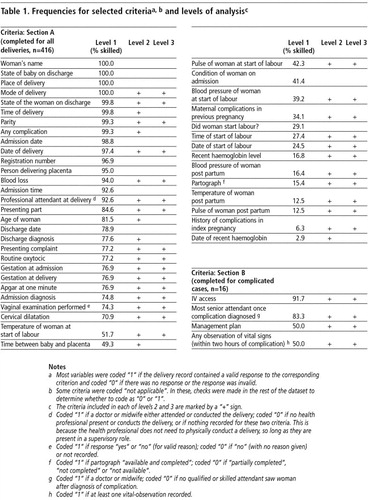

The aim of the data analysis was to quantify and summarise the level of skill provided at delivery based on the records kept. Criteria on the case extraction form were coded according to whether they indicated skilled attendance (coded “1”) or care falling short of skilled attendance (coded “0”). For example, if the form indicated that a blood pressure measurement was taken and the value recorded was plausible, then the criterion would be coded “1”. If there was no value recorded or it was implausible, then that criterion would be coded “0”. Implausible values refer to measurements that were out of scale (for example, a body temperature of 7°C in a normal delivery). The complete coding schedule is included with Table 1.

Box 1. Definition of a complicated deliveryCitation13

For the purposes of this study, cases were defined as complicated if any of the following conditions were recorded:

Haemorrhage: antepartum or post-partum

Prolonged or obstructed labour

Post-partum sepsis

Pre-eclampsia/eclampsia

Retained placenta

Retained products of conception post-partum

Ruptured uterus

Section A of the case extraction form contains criteria of standard delivery care for all cases (with and without complications). Section B was only filled in for deliveries with complications, and four key criteria were selected as markers of skilled care common to most serious complications. Our definition of cases with complications (Box 1) was based on the UNICEF/WHO/UNFPA GuidelinesCitation13 but adapted to include only the complications pertaining to delivery care, thereby excluding abortion complications and ectopic pregnancies.

Summary measures of skilled attendance were based on responses to all the criteria in section A for all deliveries, and including section B for complicated deliveries. A variable was created equal to the sum of the codes for each record, resulting in a score that can be used as a summary measure of the skilled attendance recorded at each delivery. The score is reported as a percentage of the maximum possible score.

By pooling the data across deliveries, cumulative frequencies, mean and median percentage scores were produced. Mean percentage scores were stratified by type of attendant (doctor, midwife, midwife assistant) and place of delivery (government hospital, mission hospital, government health centre and private maternity home). The t-test was used to calculate statistical significance of differences observed.

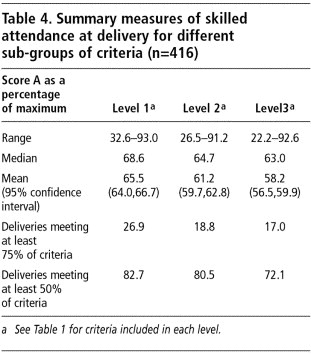

Our basic analysis included all criteria as described above and listed in Table 1. This analysis was termed Level 1. Unless stated otherwise, results are presented for this basic analysis of all criteria. In addition, to make the scores more specific to the immediate clinical needs during a delivery, two sub-groups of the criteria were selected to produce scores indicating different levels of skilled attendance, identified as Levels 2 and 3. The criteria included in each of these levels are marked by a “+” sign in Table 1. Levels 2 and 3 were formulated by a panel in Aberdeen midway through the analysis. The levels are included as an illustration of ways in which the data can be handled to allow for the relative importance of different criteria. Level 2 included criteria which the panel felt were relevant to the clinical welfare of the woman or her baby and excluded criteria which were either administrative in nature (for example, registration number) or which were unlikely to directly affect the medical condition of the woman or baby, such as recording of the woman's name, or the person who delivered her placenta–even though recording of some of these items would normally be considered good practice. Level 3 further reduced the criteria to include only those deemed essential for clinical decision-making, such as mode of delivery, amount of blood loss or completion of partograph.

Results

Specific components of delivery care

Table 1 illustrates the coding and criteria included in the calculation of scores for Levels 1, 2 and 3. This table also shows the frequencies of specific criteria for Kintampo District. The least well recorded criteria were the date of recent haemoglobin measurement (2.9%) and current pregnancy complications (6.3%). Post-partum vital signs were also frequently not recorded. A fully completed partograph was available in only 15.4% of delivery records. Monitoring of vital signs at the start of labour were met in 39.2% to 51.7% of cases. Components more commonly recorded were Apgar score at delivery (76.9%), cervical dilatation (70.9%) and blood loss in 94.0%. Examples of items recorded in over 90% of records include registration details, times and dates of delivery and admission, mode and place of delivery, parity, estimated blood loss, and baby's discharge condition.

Summary measures of skilled attendance

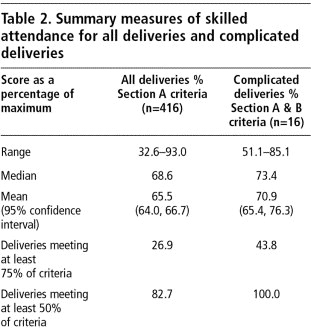

Table 2 shows aggregated measures of skilled attendance for all deliveries and for complicated deliveries. For all deliveries, 32.6% to 93.0% of criteria were met for “standard care” (defined by Section A criteria), with a mean of 65.5%. No delivery met all of the criteria. This range is wide and does not provide a picture of the types of deliveries that fail to meet most criteria. Another way of expressing the summary estimates was to determine the proportion of records meeting a certain threshold of criteria, arbitrarily divided into quartiles and termed the Skilled Attendance Index (SAI). All records met a quarter of the criteria, 82.7% met half of the criteria and 26.9% of records met at least three-quarters of the criteria for skilled attendance.

For complicated deliveries, the small numbers available (n=16) allow only limited interpretation. In these deliveries, an average of 70.9% of the criteria were met, and the SAI shows that 43.8% of records satisfied at least three-quarters of the criteria for skilled attendance. This would suggest that 16.9% more deliveries with complications received skilled attendance than deliveries with no complications, although this difference is not statistically significant (p-value for the difference in proportions=0.14).

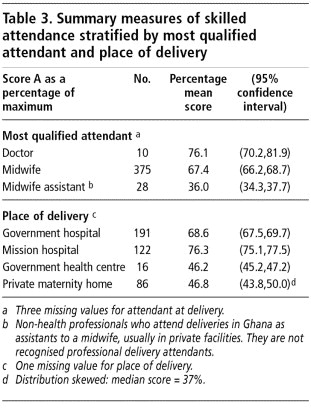

Table 3 presents summary measures stratified by attendant. Doctors, with a mean score of 76.1%, appear to satisfy more criteria than midwives at 67.4%, who in turn satisfy more criteria than assistant midwives, a non-professional grade of staff in private facilities in Ghana. The assistant midwives satisfy only an average of 36.0% of criteria. The differences between each of these mean values are significant (p<0.001).

Stratification by place of delivery found mission hospitals with the highest mean score of 76.3% criteria met, compared to deliveries in the government hospital at 68.6%. Other facilities had mean scores of less than 50%. Differences between the means are statistically significant at p<0.001.

Table 4 shows how the summary measures vary when different sub-groups of criteria are used. When the criteria are more focused on clinical parameters (Levels 2 and 3), the percentage scores for skilled attendance are lower. There is a decrease in score with increasing focus, with mean scores ranging from 65.5% for Level 1 to 58.2% for Level 3.

Discussion

Our study collected data on normal and complicated deliveries in both hospital and non-hospital facilities and thus differs from other record reviews.Citation12 Citation14 The study demonstrated the feasibility of collecting data from various types of health facilities. Data could be extracted from 10–12 records in an eight-hour working day. Forty days were required to complete the data collection for the district by one person. Three days were spent at each of the smaller health facilities with a delivery rate of less than 10 per month, 16 days at the busiest hospital (50 deliveries per month). A nurse-midwife was recruited for data collection, although others have successfully used non-medical personnelCitation12 with advantages of greater objectivity of the data collector and less disruption to clinical service provision. Other assessments of maternity care used several instruments, including structured observations, record review, inventories, patient flow studies and interviews,Citation15 Citation16 Citation17 Citation18 Citation19 rather than a single case extraction form and are likely to require even more time and resource inputs.

Reliance on record review raises issues of bias and validity even though records are widely used to assess quality of care.Citation12 Citation14Citation19 The method presupposes that what was recorded was performed and what was not recorded, not performed. Incomplete records (e.g. a missing partograph in a set of clinical case notes) can result in systematic errors. In this study, all incomplete records were included in the sample, and the missing criteria classified as not performed. If several primary data sources across different types of health facilities are used, these different sources can be inconsistent with each other. For instance, a partograph may record a delivery as spontaneous and cephalic, while the same case is recorded in the nursing notes as a breech delivery. No such instances were identified in this study, but the problem could be overcome by first identifying the most reliable type of record. Missing records are another concern; clinical case notes of maternal deaths are sometimes removed from the medical records office and kept separately. The number of missing records was not documented in this study, but enquiries later revealed this to be rare.

The frequency of complications (3.9%) in this study was much lower than the expected 15%.Citation13 Possible reasons include exclusion of non-delivery complications from the sample, under-recording and under-reporting. Women with complications may also have gone directly to other hospitals, or were referred without the originating facility recording events. However, the nearest hospitals not included in the sample were four to five hours away by private vehicle and unlikely to be accessible to many. Another reason for the disparity could be that these facility-based data and the population-based, expected 15% complication rate are not comparable.

The study generates two main types of information. The first type, possibly of greater interest to clinicians, is the frequency of each clinical action comprising skilled attendance. Availability of the enabling environment is partially captured on the basis that if drugs and equipment are available, the related clinical actions are more likely to be performed and recorded.

The second type of information is the summary measures. Alternative ways of describing these include expression of a range or mean of criteria met, or the SAI, which describes the proportion of deliveries meeting a pre-defined threshold. The main advantage of summary measures is the computation of one single composite measure rather than a series of values for several indicators of performance used in other methods.Citation18 Citation19 The method also has a degree of flexibility and can be computed in various ways, depending on the type of information required. The binary nature of the analysis, however, results in simplification which cannot reflect quality dimensions, for example when blood pressure is taken and recorded but incorrectly so. Also, the SAI does not inform on the interventions required to improve skilled attendance nor the reasons why care may be found to be inadequate, for instance whether the partograph was not used because of lack of training or lack of supplies.

Nevertheless, these summary measures are likely to be of interest to programme managers, whose priorities are to monitor and achieve overall improvements in practice. At programme level, progress could be monitored using one of the summary measures. In the event that skilled attendance is identified as sub-standard using this one indicator, then auditCitation11 or needs assessmentsCitation19 can be used to find out how to correct the problem. Once the necessary interventions are put into place, continued monitoring using the summary measure should be sufficient to indicate changes over time. If the interventions are appropriate and implemented well, the summary measure should improve. If there is no improvement, then further diagnosis will be necessary. Repeated collection of data with several instruments which generate many indicators will be unnecessary and reserved only for situations where improvements are not occurring.

Use of the summary measures for monitoring raises the question of what ultimate target or standard is required. Although the theoretical target might be that all deliveries meet all criteria, the summary measures can also monitor change from a relative perspective as more deliveries meet more criteria over time. Experience of using the summary measures may reveal a feasible “standard” of skilled attendance possible within certain settings, for instance, a mean of 90% of criteria met might be expected in a tertiary facility while in a rural health centre a mean of only 70% might be the best level achievable. Another example of how the summary measure could be used is through comparison with other indicators. National figures from the 1998 Ghana Demographic and Health Survey show that 44% of deliveries were attended by health professionals.Citation20 The SAI of 26.9% of deliveries fulfilling three-quarters of criteria suggests that not all women attended by a health professional will have received skilled care. This comparison between population-based demographic survey data and the facility-based SAI is justifiable in Ghana, as health professionals conduct very few deliveries outside health facilities. In countries where health professionals practice in the community, this comparison would be inappropriate. The method described in this study limits the assessment of skilled attendance to health facilities, but if community practitioners keep delivery records, a similar method may be used for community deliveries.

Stratification of the summary measures by type of attendant, type of facility and “levels” shows some controversial differences in skilled attendance, such as the disparity in care provided by midwives and doctors. These findings are potentially damaging to the credibility of health professionals and health services and because of the issues of validity and bias discussed, must be interpreted carefully. It is possible that doctors are trained to record events more frequently than midwives. In Ghana, doctors usually attend cases of complications where litigation is a threat, resulting in careful recording habits. Doctors tend to be employed in hospitals where resources and organisation of systems are better with writing materials, standard forms and case notes available. Midwives often work in smaller, rural facilities where paper and copies of partographs are scarce. Midwives see more cases where complications are not expected or do not occur, making recording of clinical actions seem less critical. It is therefore possible that midwives provide skilled care as or more often than doctors but are less likely to document it. Similar reasons may explain the differences observed in this study between types of facilities.

Although such differences may be exposed in initial measurements of skilled attendance, in the longer term, if monitoring is continued and staff made aware of the emphasis on record review, recording may improve and gradually reflect actual clinical actions more closely. Indeed, these changes in recording practice over time may even reverse the observed difference between doctors and midwives, as other studies of skills and competence have shown that midwives do better than or as well as doctors.Citation18

Another benefit in the longer term is that good recording is good clinical practice in itself. However, better recording does not necessarily mean that the actual care correspondingly improves. Even so, it can be argued that careful recording can encourage good practice, for example where health workers are not well informed on good practice, analysis of the records will show up areas of deficiency which can be corrected. Even where knowledge levels are adequate, increased emphasis on recording could provide opportunities for self-reflection, analysis and therefore improvements in care.

Recommendations

With these benefits and constraints in mind, our suggestions for future practical use of this tool are as follows. The method is put forward tentatively as a means of measuring skilled attendance at delivery. Further study of the method to address questions of validity and bias is necessary in the first instance. Validity of the proposed method could be established through triangulation with other means such as observational studies or interviews, although other biases may result. Where the method is applied, careful consideration of how it might affect service provision and provider practices is required. Given the time constraints discussed, monitoring is likely to be feasible only at yearly intervals and if staff can be made available to collect data. Documentation of the effects of improved recording on clinical practice over time would be of interest. To provide information on how skilled attendance can be improved, other diagnostic tools are available.Citation12 Citation16 Citation18 Citation19

Some key components of skilled care are not captured with this method, such as decision-making for referral and the practice of unnecessary procedures like routine enema use prior to delivery and routine episiotomy.Citation21 Citation22 Another crucial aspect of skilled care not addressed is the perspectives of women, which are described in other SAFE studies.Citation23

The proposed method can be used in both hospital and non-hospital health facilities. The purpose of applying these measures of skilled attendance should be seen not as an end in itself but to advance improvements in delivery care. In contrast to clinical audits, which can be threatening to health professionals who work with little support and who may have low self-esteem, the measures are presented in an aggregated form, preserving anonymity and resulting in non-punitive monitoring.Citation12 The SAI may seem complex for use in routine monitoring, but it attempts to overcome the limitations of a relatively simple indicator like “percentage of skilled attendants or health professionals” while reserving the need for repeated use of other more cumbersome quality assessment tools. To simplify application of the SAI, a field manual and computer analysis programme, which automatically computes the indices of skilled attendance, have been produced and are available on the web.Citation24

The study provides a new quantitative approach to measuring the extent of skilled attendance at delivery in health facilities through one composite index, and contributes to greater understanding of the processes and measurement of skilled attendance. Although substantive conclusions cannot be drawn from this single study, the method is proposed as an adjunct to existing indicators and tools for measuring skilled care. Refinements will be required before it can be recommended as a rigorous means to monitor skilled attendance, and like many safe motherhood indicators, will need further study in order to establish its link with health outcomes and reductions in maternal mortality and morbidity.

Acknowledgements

Dr Colin Bullough, Dr Alice Kiger, Dr Joseph Taylor and Dr Alex Quarshie commented on sampling and selection of criteria. Many individuals in the Ministry of Health, Ghana Health Service, Kintampo Health Research Centre, participating clinics and hospitals, and SAFE Project Management Team and Advisory Board made this study possible. Caroline Reeves assisted with the literature review and Lucia D'ambruoso provided a detailed synopsis of related methodologies. The SAFE International Research Partnership is co-ordinated by the Dugald Baird Centre for Research on Women's Health, University of Aberdeen, Scotland. The European Commission and the UK Department for International Development funded the SAFE study. The views expressed in this article are solely the responsibility of the authors. Dr Paul Arthur (1956-2002), Director of the Kintampo Health Research Centre until his death, facilitated the conduct of this study and is remembered with great sadness.

Notes

* In addition to the authors, the SAFE study sub-group for measurement of skilled attendance comprised: Dr Sylvia Deganus, Tema General Hospital, Ghana; Dr Vanora Hundley and Dr Birgit Jentsch, University of Aberdeen; and Dr Gloria Quansah, Ghana Health Service.

References

- F Donnay. Maternal survival in developing countries: what has been done, what can be achieved in the next decade. International Journal of Gynecology and Obstetrics. 70(1): 2000; 89–97.

- J Liljestrand. Strategies to reduce maternal mortality worldwide. Current Opinion in Obstetrics and Gynecology. 12(6): 2000; 513–517.

- World Health Organization. Making Pregnancy Safer: A Health Sector Strategy for Reducing Maternal and Perinatal Morbidity and Mortality. WHO/RHR/00.6. 2000; WHO: Geneva.

- Family Care International FCI at work. At: 〈www.familycareintl.org/work/burkina_faso.html. 〉. Accessed 10 September 2002.

- WJ Graham, JS Bell, CHW Bullough. Can skilled attendance at delivery reduce maternal mortality in developing countries?. Studies in Health Services Organisation and Policy. 17: 2001; 97–130.

- Safe Motherhood Inter-Agency Group. Skilled attendance at delivery: a review of the evidence. 2000; Family Care International: New York. (Draft).

- United Nations Statistics Division. Millennium Indicators. At: 〈http://millenniumindicators.un.org/. 〉. Accessed 10 December 2002.

- World Health Organization. Reduction of Maternal Mortality: A Joint WHO/UNFPA/UNICEF/World Bank Statement. 1999; WHO: Geneva.

- SAFE International Research Partnership for Skilled Attendance for Everyone. SAFE At: 〈www.abdn.ac.uk/dugaldbairdcentre/safe. 〉. Accessed 28 February 2003.

- BN Ong, G Humphries, H Abbett. Rapid appraisal in an urban setting, an example from the developed world. Social Science and Medicine. 32: 1991; 909–915.

- WJ Graham, P Wagaarachchi, G Penney. Criteria for clinical audit of the quality of hospital-based obstetric care in developing countries. Bulletin of World Health Organization. 78(5): 2000; 614–620.

- PT Wagaarachchi, WJ Graham, GC Penney. Holding up a mirror: changing obstetric practice through criterion-based clinical audit in developing countries. International Journal of Gynecology and Obstetrics. 74: 2001; 119–130.

- UNICEF/WHO/UNFPA. Guidelines for Monitoring the Availability and Use of Obstetric Services. 1997; UNICEF: New York.

- O Adeyi, R Morrow. Essential obstetric care: assessment and determinants of quality. Social Science and Medicine. 45(11): 1997; 1631–1639.

- A Jahn, M Dar Iang, U Shah. Maternity care in rural Nepal: a health service analysis. Tropical Medicine and International Health. 5(9): 2000; 657–665.

- S Miller, M Cordero, AL Coleman. Quality of care in institutionalized deliveries: the paradox of the Dominican Republic. International Journal of Gynecology and Obstetrics. 82(1): 2003; 89–103.

- Prevention of Maternal Mortality Network. Situation analyses of emergency obstetric care: examples from eleven operations research projects in West Africa. Social Science and Medicine. 40(5): 1995; 657–667.

- Quality Assurance Project. Safe Motherhood Studies–Results from Benin: Competency of Skilled Birth Attendants, The Enabling Environment for Skilled Attendance at Delivery, In-Hospital Delays in Obstetric Care (Documenting the Third Delay). November 2003. At: 〈www.qaproject.org/oper/orsafe.html. 〉. Accessed 23 April 2004.

- World Health Organization. Safe Motherhood Needs Assessment. WHO/RHT/MSM/96.18 Rev 1. 1996; WHO: Geneva.

- Ghana Statistical Service, Macro International Inc. Ghana Demographic and Health Survey, Calverton, MD, 1998.

- P Buekens. Overmedicalisation of maternal care in developing countries. Studies in Health Services Organisation and Policy. 17: 2001; 195–206.

- M Enkin, MJNC Keirse, J Neilson. A Guide to Effective Care in Pregnancy and Childbirth. 3rd ed, 2000; Oxford University Press: New York.

- J Bell, J Hussein, B Jentsch. Improving skilled attendance at delivery: a preliminary report of the SAFE Strategy Development Tool. Birth. 30(4): 2003; 227–234.

- SAFE International Research Partnership for Skilled Attendance for Everyone. SAFE Resources. Strategy Development Tool Module 4. At: 〈. www.abdn.ac.uk/dugaldbairdcentre/safe/resources.hti. 〉. Accessed 28 February 2003.