Abstract

Since 1965, Turkey has followed an anti-natalist population policy and made significant progress in improving sexual and reproductive health. This paper presents a critical review of the national reproductive health policies and programmes of Turkey and discusses the influence of national and international stakeholders and donors on policy and implementation. While government health services have played the primary role in meeting sexual and reproductive health needs, international donor agencies and national non-governmental and other civil society organisations, especially universities, have played an important complementary role. Major donor agencies have supported many beneficial programmes to improve reproductive health in Turkey, but their agendas have sometimes not been compatible with national objectives and goals, which has caused frustration. The main conclusion of this review is that countries with clear and strong reproductive health policies can better direct the implementation of international agreements as well as get the most benefit from the support of international donors.

Résumé

Depuis 1965, la Turquie applique une politique antinataliste et a accompli des progrès sensibles en santé génésique. Cet article présente un examen critique des politiques et programmes nationaux de santé génésique en Turquie et analyse l'influence des acteurs et donateurs nationaux et internationaux sur les politiques et leur application. Les services de santé publics ont joué un rôle de premier plan pour répondre aux besoins, mais les donateurs internationaux et les organisations non gouvernementales nationales et autres entités de la société civile, particulièrement les universités, ont eu une action complémentaire non négligeable. Les principaux organismes donateurs ont soutenu nombre de programmes bénéfiques pour améliorer la santé génésique, mais leurs buts n'étaient pas toujours compatibles avec les objectifs nationaux, ce qui a provoqué des frustrations. La principale conclusion de cet examen est que les pays appliquant des politiques de santé génésique claires et solides peuvent mieux diriger la mise en œuvre des accords internationaux tout en bénéficiant le plus de l'appui des donateurs internationaux.

Resumen

Desde 1965, se ha seguido una polı́tica de población antinatalista en Turquı́a y se han logrado considerables avances para mejorar la salud sexual y reproductiva. En este artı́culo se presenta una revisión crı́tica de las polı́ticas y los programas nacionales de salud reproductiva en Turquı́a y se analiza la influencia que ejercen las partes interesadas y los donantes, tanto a nivel nacional como internacional, en las polı́ticas y en su aplicación. A pesar de que los servicios de salud gubernamentales han desempeñado un papel primordial para cubrir las necesidades de salud sexual y reproductiva, las agencias donantes internacionales y las organizaciones nacionales no gubernamentales y otras entidades de la sociedad civil, en particular las universidades, han desempeñado un importante papel complementario. Las principales agencias donantes han apoyado muchos programas benéficos para mejorar la salud reproductiva en Turquı́a, pero sus agendas no siempre han sido compatibles con los objetivos y las metas nacionales, lo cual ha causado frustración. La conclusión principal lograda con esta revisión es que los paı́ses con polı́ticas de salud reproductiva claras y fuertes pueden dirigir mejor la ejecución de los acuerdos internacionales y obtener un mayor beneficio del apoyo de los donantes internacionales.

The UN International Conference on Population and Development (ICPD) in Cairo in 1994, called upon countries to make reproductive health information and services accessible through the primary health care system to all individuals of appropriate age by 2015.Citation1

The ICPD+5 in 1999 showed that countries had not allocated sufficient resources and had limited institutional capacity to achieve these goals. Donors had also not contributed the financial support they had promised at the ICPD that was required to implement the ICPD Programme of Action.Citation2 This paper presents a critical review of the national reproductive health policies and programmes of Turkey and discusses the influence of national and international donors and stakeholders on policy and implementation.

Turkey has over 67 million population, 98% Muslim, and bridges Asia and Europe. It is among the 20 most populous countries in the world and the most populous in the region, with a young population, of whom about 50% are under the age of 20.Citation3 The annual population growth rate was 14 per 1000 by 1997; the crude birth rate was 23.4 per thousand and the crude death rate 6.7. Life expectancy at birth was 66.2 years for men and 70.9 years for women in 1997.Citation4

The country has a highly heterogeneous social and cultural structure. Family ties are strong and influence the formation of values, attitudes, aspirations and goals. Although laws can be considered to be liberal in relation to gender equality, patriarchal ideology still characterises social life. Therefore, women in Turkey live in a highly complex social and cultural structure that affects their social status and their health, especially reproductive and sexual health.Citation5 Citation6 Citation7

Women gained many rights in the fields of education, law and politics, and other social rights after the foundation of the Republic of Turkey in 1923, which also had a positive influence on women's health.Citation7 However, gender inequalities still exist in many spheres of life. The literacy rate has remained lower for women than for men since 1935. In 2000, about twice as many men as women completed schooling for all years from grade six through university.Citation3 Citation7 Until recently, five years of primary school education was compulsory in Turkey; this was raised to eight years from 1997.Citation3 Gender differences in education are a key factor in the utilisation of health services such as antenatal care, delivery and family planning, and contact with health personnel by women of reproductive age.Citation7 Citation8 Citation9 Citation10

Health care system and health policy in Turkey

Under the current Turkish health care system the Ministry of Health (MoH) is responsible for designing and implementing nationwide health policies and providing health care services. Other public institutions like the Social Insurance Institution, universities, the private sector and non-governmental organisations (NGOs) also contribute to providing health care services. Some other government ministries, e.g. the Ministries of Education, Labour and Defense, and public organisations such as the municipalities and the Turkish Postal Administration, also operate their own hospitals for their employees and their dependents.Citation11 Only the MoH provides primary health care services, however.

At the central level, the MoH has the authority to take all strategic decisions and is also responsible for the implementation of preventive health care services throughout the country, based on the principles of primary health care, established in 1961 under the Socialisation of the Health Care Services Law,Citation12 which aimed to provide health care services free or at low cost at the point of delivery and also expand health care services to make them easily and equitably accessible to the whole population, offer integrated health services at grassroots level through a team approach, and create community participation.Citation13

Turkey has been implementing a comprehensive family planning programme since 1965 that has been successful in improving the use of modern contraceptives. After extensive advocacy efforts by the Turkish Family Planning Association, an NGO founded in 1963, the first anti-natalist population planning law was enacted in 1965, which had a great impact on women's reproductive health. This law legalised the provision of information and education on contraception and clinical services for the range of reversible contraceptive methods. Surgical sterilisation and induced abortion were permitted only on eugenic and medical grounds. The General Directorate of Maternal and Child Health and Family Planning (MCH-FP) was set up in 1965 after the First Population Planning Law was passed, and is an organ of the MoH. Its responsibilities are to develop policies and strategies, and to evaluate maternal and child health and family planning programmes nationally.

The second population planning law of 1983Citation13 Citation14 authorised mid-level providers to insert IUDs, legalised induced abortion on request up to 10 weeks of pregnancy and licensed general practitioners (GPs) to terminate pregnancies. Sterilisation on request was also legalised. Most of the scientific evidence put forward for these policy changes was provided by the Department of Public Health, Hacettepe University Medical School, based on evidence from operations research carried out in collaboration with the Special Programme of Research, Development and Research Training in Human Reproduction at the World Health Organization (WHO HRP) and the MoH.Citation15 Citation16 Over the years the family planning programme has been expanded to cover other aspects of women's health and reproductive health. Several different agencies and institutions such as national NGOs, universities and the MoH have a long history of collaboration with the international agencies to provide reproductive health programmes and services.

Reproductive health status in Turkey

Since 1963, a nationwide Demographic and Health Survey (DHS) has been carried out every five years in Turkey, which provides a basis for observing trends in health. Recent decades have witnessed dramatic declines in the fertility rate. In the early 1970s the total fertility rate was around 5 children per woman; this had declined to 2.6, according to 1998 DHS data, though with a big difference between the western (2.0) and eastern (4.2) parts of Turkey. The infant mortality rate was 200 per 1000 live births in 1963, and 35.3 for the year 2000. The perinatal mortality rate is still high at 42 per 1000 total births, which indicates a continuing need for improvement in the health of mothers in the perinatal period.Citation17

The maternal mortality ratio (MMR) was around 200 per 100,000 live births in the 1960s and had declined to 132 in 1982. According to research in 1997–98 in 615 hospitals in 53 provinces of Turkey, the MMR was 49.2 per 100,000 live births. Post-partum haemorrhage was the leading cause of death; four out of five deaths were due to preventable causes.Citation18 Citation19

Over the years, the coverage of antenatal care has been increasing and included 68% of all pregnant women in 1998. However, on average one in three pregnant women still does not receive antenatal care. The proportion of women receiving antenatal care rises markedly with level of education.Citation8 Citation9 The proportion of safe deliveries was 81% in 1998, which means one in five pregnant women is still delivering at home assisted by traditional birth attendants in Turkey.Citation17

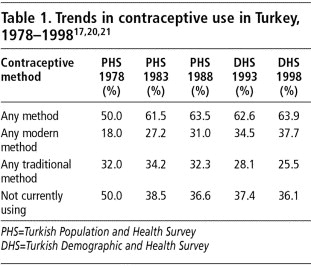

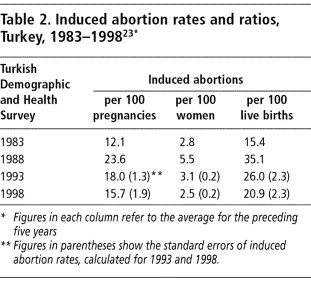

Contraceptive prevalence was 64% in 1998, of which modern contraceptive use comprised 38% and traditional contraceptive use 26%. Unmet need for family planning is 10% and, thus still relatively high.Citation17 Although abortion is not accepted as a contraceptive method under the national family planning policy of Turkey, it has definitely contributed to the declining total fertility rate in Turkey over the years.

Before abortion was legalised in 1983, unsafe abortion was a serious problem in the country but the number of abortions was not recorded accurately because they were illegal.Citation22 After 1983 the rates of induced abortion increased initially, due mostly to better reporting. In the 1990s, due to post-abortion family planning programmes the abortion rate started to decrease and the downward trend is still continuing (Table 2).Citation23

In spite of the many gains, a number of indicators related to reproductive health did not improve significantly in the 1980s and 1990s in Turkey. Early marriage remains an important problem, for example, and affects adolescent sexual and reproductive health. According to the 1998 DHS, 15.5% of women aged 15–19 were married; the median age at first marriage was 19.7 for women aged 25–49 and 23.6 for men aged 25–64. In general, the age at first marriage and women's educational status are lower in the eastern and rural areas of the country, which causes social problems and a higher risk of obstetric complications.Citation17 Traditionally, premarital sexual activity for women is stigmatised and condemned. Talking about sexuality remains taboo among many parents in their relationship with adolescents, no matter what stratum of the society or cultural, ethnic and educational background they are from. On the other hand, different attitudes and behaviour with regard to premarital sex can be found today, especially among young people at university in big cities.Citation24

Other major concerns are regional as well as rural–urban differences in indicators, which are very marked.Citation17 Citation20 Citation25Citation26 The educational level of women might be an important factor in this. The proportion of women aged 14 years and over with at least a primary education was 7.9% in 1975 and had increased to 26.6% in 2000, but despite this increase, currently 19.4% of all women are not literate, and a difference between urban and rural areas still exists.Citation3 Since 1980, the high migration flow from rural to urban areas has created new squatter areas around the big cities, which might affect access to health services.Citation27 Citation28 Citation29 Primary health care services, including reproductive health and family planning, have not been sufficiently provided in the squatter areas. The low educational level of women living in the squatter areas may also be an obstacle for them to seek these services.

Resources for reproductive health: financial and human

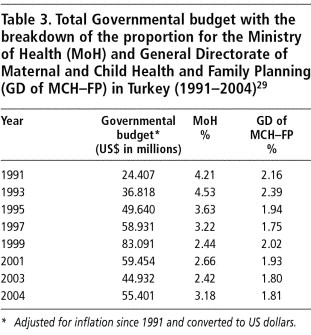

The MoH and the General Directorate of MCH-FP each cover some of the costs of reproductive health and family planning services. Family planning commodities, such as contraceptives, equipment and educational materials are covered from the General Directorate's Budget. The cost of personnel, maintenance and clinic buildings are met from the MoH budget as well as all other health expenditures such as immunisation, environmental health, mental health, some parts of curative services and administrative costs. The proportion of funds allocated to the MoH and the General MCH-FP from the total national governmental budget is shown in Table 3.

Although the Ministers of Health have made great efforts to increase the MoH budget, over the years the proportion of money allocated to the health budget has not been increased very much. This is also the case for the General Directorate of MCH-FP budget. The following problems are examples of obstacles in the provision of reproductive health and family planning services:

Collaboration between the units in the MoH is very poor. For example; the General Directorate of Primary Health Care manages the maternal and neonatal tetanus elimination programme, but the General Directorate of MCH–FP manages the safe motherhood programme. Unfortunately, there is only occasional communication between the two.Citation30

Bureaucratic procedures for spending the budget of the General Directorate of MCH–FP are very complex, which causes wasting of time and resources. Even to buy material such as syringes or contraceptives for the clinics takes at least three months.Citation31

Turnover among health personnel is very high. Qualified personnel are changed and sometimes a new staff person is not skilled in delivering reproductive health services. The MoH then has to train new personnel all the time in order to maintain the services. In addition, the distribution of health personnel across the country is not well balanced between rural and urban and western and eastern regions.Citation32

Effects of ICPD 1994 on reproductive health in Turkey

The ICPD in Cairo in 1994 significantly affected women's health programmes and strategies in Turkey, and led to many innovative activities that changed traditional attitudes and practices.Citation16 Thus, for example, traditional MCH–FP approaches in primary health care services were changed, and maternal health was replaced by women's health, and a comprehensive, life-cycle approach to reproductive health was adopted which covers the reproductive health needs of both men and women of all ages, including for fertility regulation, sexually transmitted infections (STIs) and HIV/AIDS.

One of the most important outcomes of the ICPD was the preparation of a “Women's Health and Family Planning Strategic Plan” in 1995, through inter-sectoral collaboration between the government and NGOs in Turkey, under the guidance of the General Directorate of MCH–FP and with the financial support of UNFPA. In the action plan, all recommendations of the ICPD Programme of Action, especially on reproductive rights and reproductive health, were adopted according to the country's needs. It was meant to be a realistic plan for motivating and guiding policymakers and managers at the central and local levels. This strategic plan emphasised strengthening the sexual and reproductive health components of primary health care units, with the aim of minimising regional differences in health indicators, improving quality of services and involving NGOs such as the Turkish Family Planning Association and Family Health and Planning Foundation, which have significant inputs into reproductive health care activities in the country, especially with regard to advocacy activities. All possible efforts such as convincing and motivating the donors and stakeholders to increase inter-sectoral collaboration to improve the social status of women were also emphasised in the strategic plan.

Just before the ICPD a Special Expert Committee on Reproductive Health and Family Planning was established within the State Planning Organisation in 1993 to contribute to the preparation of the 7th Five-Year Development Plan in 1994.Citation16

The Family Planning Advisory Board, which was established under the Ministry of Health in 1993 and situated in the General Directorate of MCH–FP to facilitate inter-sectoral collaboration and cooperation, also monitors and follows up the implementation of policies and programmes, and indicators to monitor progress in family planning. This Board was re-organised after ICPD and renamed the Women's Health and Family Planning Advisory Board. It includes ten permanent representatives from various sectors (Ministries of Education, Labour, Media, Religious Affairs, Universities and the Army) and representatives from NGOs, civil society organisations and other sectors, depending on the agenda of each meeting. It meets twice a year, chaired by the Minister of Health, and reports to the Minister through the General Directorate of MCH–FP. This Board serves as an excellent mechanism to motivate all sectors to initiate new approaches, new projects and programmes in accordance with ICPD recommendations. For example, it has successfully launched education for adolescents on sexual and reproductive health in schools and education for soldiers to improve male involvement in fertility regulation and family planning.Citation16 Citation25

In order to reduce the unment need for family planning and increase contraceptive choice, implants and injectables were introduced into the national family planning programme with the technical and financial support of AVSC (now Engender Health), a New York-based NGO with a Turkish office. Since the completion of the introductory study in 1997–98, two types of injectables (monthly and three-monthly) have been available.Citation25 Citation33

Another important activity was the development of national service guidelines on family planning, which also cover most other reproductive health topics, including counselling, sexuality, STIs and HIV/AIDS, termination of pregnancy, infertility, infection prevention, quality assurance, and recording data on family planning services. These were published and distributed to all primary health care units in 1994 with the support of the Johns Hopkins Program for International Education in Gynecology and Obstetrics (JHPIEGO).Citation34

Safe motherhood initiatives were launched in eight pilot provinces with the support of UNFPA and UNICEF.Citation25 As part of the safe motherhood programme, community-based reproductive health services such as family planning, antenatal care, delivery and post-natal care were piloted in rural as well as urban areas of those provinces by four NGOs (Turkish Family Planning Association, Hacettepe Public Health Foundation, Human Resources Development Foundation and Turkish Family Health and Planning Foundation) with the support of UNFPA.

Counselling services for family planning have also been improved in order to ensure informed choice and maintain high continuation rates. These activities were mainly supported by AVSC.Citation16

As suggested at the ICPD and also in the national plan, some pilot post-partum and post-abortion family planning programmes were initiated, and in a few hospitals in the large cities these services are now provided.Citation16 Citation25

Undergraduate medical and nursing–midwifery school curricula on family planning were improved in 1992–98 by Hacettepe University Department of Public Health and the MoH, with the support of JHPIEGO, and teaching activities are still continuing.Citation16 Citation21 Citation26

Some of the MCH-FP Centres in crowded urban squatter areas that have close links with nearby hospitals and health centres have been selected to be converted into free-standing Family Health Clinics, which was tested in Ankara, Adana, Şaanlıurfa and Diyarbakır.Citation16 Citation25 The main purpose of this approach was to expand the range of reproductive health care services at primary level (i.e. pregnancy termination, tubal ligation and vasectomy, prevention and treatment of STIs, services for adolescents, post-menopausal and elderly women, and early screening and diagnosis of reproductive cancers), to avoid people having to be involved in the complexities of attending a hospital. This innovative project was initiated in 1995 and after a two-year trial, an evaluation was carried out in 1997 in one of the clinics. The results were very favourable. Quality of care was improved as well as utilisation of services and an expanded range of services became available in areas where the demand was high.Citation16 Citation25

Since routine service statistics were not sufficient on the causes of maternal mortality in Turkey, special epidemiological research was carried out in 1997–98 by the MoH, with the collaboration of Hacettepe University Public Health Department, WHO and UNFPA.Citation18 Citation19

In addition, several special programmes were set up to strengthen information, education and counselling (IEC) materials on reproductive health. Three centres were opened in three geographic areas in Turkey by the MoH, which produced IEC materials with the technical and financial support of the Japanese International Cooperating Agency (JICA).Citation25

The activities to involve men in reproductive health programmes, especially for family planning and STI care, have been particularly important in a male-dominated society like Turkey. The Turkish Family Planning Foundation initiated a special programme with the collaboration of the military to implement IEC programmes on reproductive health for young men doing compulsory military service. The programme is still continuing on a large scale.

Thus, after the ICPD, the MoH, supported by international donors as well as national NGOs in Turkey, has initiated many significant reproductive health programmes. However, although many of the programmes have been very successful as pilots, many of them have unfortunately not been replicated around the country by the national health authorities due to lack of political commitment and mismanagement.

The role of Turkish NGOs and civil society organisations

CSOs and NGOs are indispensable for strengthening a society and community. They can deal more openly with issues that are sensitive and not as easy for public sector decision-makers to deal with, including sexual and reproductive health and rights and obligations; hence, empowering them has been crucial in Turkey, as elsewhere.

NGO provision of sexual and reproductive health services has been significant in assisting the Turkish government in meeting its goals. NGOs have provided a variety of health services, targeted interventions to improve the major determinants of health and fertility, and been involved in advocating health policies and laws. The involvement of other CSOs such as the Turkish Medical Association, Turkish Nurses and Midwives Association and Turkish trade unions has been increasing, but their role is still less than that of NGOs in Turkey.

NGOs have especially carried out IEC and advocacy activities and some clinical services through outreach and community-based services. Most CSOs and NGOs in Turkey have limited resources and sustainability problems, and do not have the capacity to raise funds for themselves. Hence, there are a number of examples of service activities that have had to be stopped when donor funding has ended. For example, in the past, the Pathfinder Fund supported an NGO called Foundation for Strengthening Turkish Women, to provide family planning services in several provinces using community-based distribution and mobile clinics. These activities stopped when the funding was stopped.Citation35 The only way they could have been continued was if the services were operated on a cost–recovery basis to generate income, contracted by the government or supported from the public sector budget in some other way, or by external donor funding.

There are also some NGOs with similar objectives, which may cause duplication in their activities. For example, the Turkish Family Planning Association, Turkish Family Health and Planning Foundation, and Human Resources Development Foundation all produce IEC materials on family planning methods for the same audiences, and conduct training programmes for the same target groups and on the same issues–sometimes giving out different messages. Another example are the Turkish Association for Fighting AIDS and the Association to Fight AIDS, both NGOs established with the same objectives. From time to time, they compete with each other by organising biannual AIDS congresses in the same period, which drains domestic resources unnecessarily.Citation36 Citation37 Establishing better communication and collaboration between NGOs is necessary to save resources and to strengthen capacity.

Universities have also played a significant role in improving sexual and reproductive health in the country, through teaching, training and research programmes. Hacettepe University Medical School, Department of Public Health began to do this under the guidance of the late Professor Fişek and continues in a pioneering role in many areas of reproductive health, including training of midwives and physicians on IUD insertion; training of trainers on family planning, counselling and other reproductive health topics; development of IEC materials for family planning; pilot studies of injectable contraceptives, medical abortion and implants; operations research on voluntary surgical sterilisation; post-partum and post-abortion family planning programmes; and adolescent sexual and reproductive health services.Citation38

Other examples are the Hacettepe University Institute of Population Studies, which is the only demography institute in the country. Since 1968, every five years this institute has carried out a DHS-type survey, which provides unique data on fertility and demography for evaluating reproductive health in Turkey. Furthermore, at 14 universities in the country there are Research and Implementation Centres on Women's Issues where mainly gender issues are studied and some advocacy activities carried out.

Effects of donor support on reproductive health programmes in Turkey

While Turkey has been making significant progress in improving sexual and reproductive health, many constraints and obstacles have been encountered. From time to time national and international stakeholders have influenced both policies and practices. Due to the limited governmental budget, and other financial constraints, in order to test new approaches in reproductive health issues, the government has asked international agencies for support for projects and programmes.

From the late 1970s, the US Agency for International Development (USAID) began providing population assistance to Turkey. Until 1995, 90% of Turkey's contraceptive commodities were provided by USAID, and were distributed free of charge at primary health care centres, contributing to lower fertility rates. As part of their sustainability plan for population activities in Turkey, USAID began to reduce their funding for population activities in the mid-1990s, starting with a phase-down plan leading to the gradual termination of contraceptive commodity donations.Citation26 Thus, USAID funding for contraceptives was US$1.8 million in 1995 and $1.6 million in 1996, with no MoH procurement in those two years. In 1997, USAID funding was $0.9 million, while the MoH spent $0.6 million. In 1998 the split was $0.4 from USAID and $1.4 from MoH, and in 1999 there was no longer any funding for contraceptives from USAID and the MoH spent $2.7 million.Citation33 Currently, the Ministry of Health pays for all contraceptive commodities from its own resources and has not faced noteworthy problems in doing so; thus, in this respect, Turkey can stand comfortably on its own feet.

The second type of assistance provided by USAID has been through contractual agreements with several US-based collaborating agencies that have implemented programme activities in collaboration with the MoH, mainly to introduce new materials and techniques to improve the quality of family planning services, for example:

Even before surgical sterilisation was legalised in Turkey, JHPIEGO introduced laparoscopic techniques in the country.

EngenderHealth have been assisting the MoH since the late 1980s to improve the quality of family planning services by developing IEC materials, introducing new techniques for tubal ligation (mini-laparotomy) and vasectomy (non-scalpel) and training physicians in these techniques. This collaboration has been very productive and all activities supported by AVSC have been adopted and scaled up nationally in Turkey. With AVSC leadership in expanding the availability of sterilisation, the prevalence of tubal ligation increased from 2.9% in 1993 to 4.2% in 1998.Citation33

SEATS (Family Planning Service Expansion and Technical Support Project), another collaborating agency of USAID, assisted the Social Insurance Organisation (SSK) to establish family planning clinical services in their facilities and also to develop IEC materials in 1994–98. That assistance led to over 100 family planning clinics being opened within SSK hospitals in five years and the regulatory barriers being overcome so that they could provide contraceptives to their patients free of charge. However, the sustainability of these services in approximately 50% of the clinics proved not to be possible after the pilot phase of the programme was completed due to administrative and bureaucratic problems.Citation39

UNFPA is another major donor in Turkey to assist reproductive health care activities. UNFPA began cooperation activities with the Government of Turkey in 1971, initially on a project-by-project basis, and now its support is continuing through a five-year country programme for 2001–05. Compared to all the other donors providing funds to Turkey, UNFPA has been the one to assist Turkey in setting up comprehensive reproductive health care activities, such as for adolescent reproductive health, safe motherhood and STIs, and working with national NGOs on research activities in relation to development, population and health and a gender-sensitive advocacy programme in line with the objectives of the ICPD Programme of Action. The main objectives of this country programme are to extend access to high quality reproductive health care and family planning services to underserved peri-urban and rural populations, which has helped to minimise inter-regional and gender-related disparities in health service provision and counselling, to integrate reproductive health into primary health services, and to improve the national policy framework.Citation40

A number of important lessons can be drawn from the activities supported by UNFPA such as providing quality reproductive health and family planning services on the basis of individual choice, and advancing a strategy that focuses on meeting the individual needs of women and men based on empowering women rather than achieving demographic targets. However, some successful programmes have not been expanded (e.g. community-based reproductive health services), and although UNFPA makes a five-year country plan for its activities, the lessons learnt from the previous five-year period have not always been taken into consideration in the next plan. For instance, in the past there was a very successful pilot programme for safe motherhood set up in eight provinces in Turkey; in the current five-year plan, however, there are no plans for continuation (let alone expansion) of the pilot projects.Citation25 Citation40 That might be due to the influence of UNFPA's central policy or the ambiguous policies of the national health authorities due to a high turnover rate of health personnel and decision-makers nationally.

Another major donor is the European Union (EU). Before 2001, some financial support was provided for some small projects related to strengthening family planning in-service training programmes and STI care. However, during this time many Turkish NGOs tried very hard to get assistance from the EU to run activities that would increase the demand for reproductive health services in the country. In fact, due to the ambiguity of EU policies related to such support and also its managerial infrastructure and complicated bureaucracy, and despite vigorous efforts by both NGOs and the MoH to get financial support from the EU, these efforts have not yet come to fruition.Citation41

At the end of 2001, the Government of Turkey and the European Commission signed a bilateral agreement for technical and financial support for the reproductive health programme for four years, starting January 2003.Citation41 The aim is to improve sexual and reproductive health, especially among women and youth, increase the utilisation of services and improve the policy environment to better support sexual and reproductive rights and choices through significantly improving the availability, accessibility, utilisation and quality of care. Five priority areas of intervention were agreed: safe motherhood, emergency obstetric care, family planning, STIs/HIV/AIDS and adolescent reproductive health. So far a needs assessment has been done in several areas and currently training modules are being developed on the priority areas.Citation42

Thus, donor support has been significant and for quite a long time donors have supported important projects in Turkey, e.g. the introduction of modern fertility regulation methods, such as implants, injectable contraceptives, medical abortion, manual vacuum aspiration for early abortion and surgical sterilisation, as well as training of trainers, infection prevention, counselling and quality of health care, mostly in relation to fertility regulation. Outside support for research and projects, as mentioned earlier, has had a very positive impact on reproductive health policies and practices, especially operations research supported by WHO HRP, which has provided a successful example of how international perspectives can be integrated into a country's policies and practices in accordance with the country's actual needs.

However, other donors have supported only programmes and projects that fit their own agendas and vision, rather than considering the actual needs of the country, which has caused frustration as well as diminished the benefits of funding for the country. Some examples follow.

A national guideline for providing family planning services was developed in two volumes, with the assistance of JHPIEGO (with USAID funding). This was published in 1994 and widely disseminated with a family planning handbook, which has been very helpful in standardising clinical practices. However, in 2000, when the guideline was being updated, USAID insisted that the chapter on abortion should be removed; otherwise, they warned the MoH, they would withdraw their assistance.

This is a typical example of how a donor agency can use funding to force the nationals of another country to accept their own policy and interests. In fact, in Turkey complications of unsafe abortions used to cause many maternal deaths; hence, Turkey made great efforts to legalise abortion to prevent this type of maternal mortality, and fortunately succeeded in this. Now, for induced abortion up to ten weeks there are no restrictions, and it is necessary in the national guidelines to have a chapter on this issue to contribute to improving the quality of service delivery. But the attitude of USAID was rigid, and the chapter on abortion was removed from the guidelines. This should not be seen as a small example; it is a very serious one and shows the attitude of donors who hold the power in terms of money. However, it certainly also demonstrates the willingness of the national authorities to give in to such demands. Neither behaviour is acceptable as it threatens both public health and women's health.

Another example was in 1995, when UNICEF and UNFPA initiated safe motherhood programmes with the collaboration of the MoH. In the four provinces where the programme was supported by UNICEF, the newborn component was strong but the care for women was rather weak. In the four provinces supported by UNFPA the maternal health care component was stronger. The MoH made a great effort to standardise the programmes across all eight provinces and convince these two donors that it should do so.Citation25 Citation28 Citation43

In sum, the contribution of international donors has been to support innovative programmes, from which we in Turkey have gained experience, and our national capacity and skills have been strengthened. In addition, collaboration between government and NGOs has been facilitated. There have only been problems when international donors have insisted on their own agenda rather than supporting national needs.

Lessons learnt and recommendations

The following are recommendations we would make for future work in Turkey, based on our experience, that may also be useful for other countries. Past and current data in Turkey show that reproductive health is a crucial public health issue. The country has long been aware of the importance of family planning policies and programmes on fertility regulation, which Turkey has strengthened over the years, since 1965. Donor support has helped the country to reach many of its health goals, including for reproductive health. Although considerable progress has been made, however, the agenda is still unfinished.

ICPD introduced the concept of a comprehensive life-cycle approach, which is well accepted in Turkey, with one proviso–that this approach should not weaken our family planning and fertility regulation activities. In order to avoid such an outcome, developing countries should have a clear, long-term agenda for their health policies and programmes, and define and specify their priority areas in reproductive health, which should not be influenced by the political environment, whether internal or external.

The main conclusion of this review is that countries with clear and strong reproductive health policies can better direct the implementation of international agreements as well as get the most benefit from the support of international donors. They need clear national targets, objectives and programmes with strong political commitment.

Donors should tailor their agendas and type of support according to the needs of countries. Certainly donors should not force countries to accept policies arising from their own political climate, but should respect the actual needs, policies and laws of the countries concerned.

When pilot projects that are set up with donor support prove to be replicable, they should be scaled up rather than terminated or continued at pilot level for many years. Evaluation should be a part of pilot studies and a lessons-learnt approach should be used.

A mechanism for intersectoral collaboration is extremely useful and should be established, or an existing mechanism should be used effectively. The MoH should establish a Coordinating Committee on Population and Reproductive Health to plan and coordinate national and international donor and stakeholders' support in Turkey, and serve as a mechanism for national and international stakeholders and donors to collaborate on relevant reproductive health and family planning activities.

Every effort should be made to use internationally accepted indicators to evaluate progress in all components of reproductive health. For this purpose, existing WHO indicators on sexual and reproductive health can be used.Citation44 Citation45 Citation46 Citation47 Work on “Health for All” indicators, initiated by WHO to evaluate overall progress in health, should be completed and countries encouraged to use them.Citation48

In conclusion, rational utilisation of existing limited national resources is the major challenge to improve reproductive health in Turkey. In future, development issues should be handled more comprehensively, i.e. not only improvements in health but also social, economic and educational indicators should be taken up together. The contributions of national as well as international donors and stakeholders to national reproductive health programmes are the key element to facilitate innovative programme development and also to bring countries in line with global agreements and achievements.

References

- United Nations. Report of the International Conference on Population and Development (Cairo, 5-13 September 1994). 1994; UN: Geneva.

- E Lule. Population and reproductive health in the Millennium Development Goals. Entre Nous. 57: 2003; 9–11.

- State Institute of Statistics (SIS). Census of Population, Social and Economic Characteristics of Population. 2000; SIS, Prime Ministry, Republic of Turkey: Ankara.

- SIS. Statistical Yearbook of Turkey 1997. 1997; SIS: Ankara.

- G Balkan, A Akin. Population Issues: Health Development and Environmental Perspectives in the World and in Turkey. 1995; MoH: Ankara.

- E Franz. Population Policy in Turkey. 1994; Deutsches Orient Institut: Hamburg.

- Women in Turkey 1999. 1999; General Directorate on the Status and Problems of Women: Ankara.

- A Akin, M Bertan. Contraception, Abortion and Maternal Health Services in Turkey: Results of Further Analysis of the 1993 Turkish DHS. 1996; MoH Turkey, Macro International Inc: Ankara, Calverton MD.

- A Akin, SB Ozvaris. Utilization of natal and postnatal services in Turkey. A Akin. Contraception, Abortion, and Maternal Health Services in Turkey: Results of Further Analysis of 1998 Turkish Demographic and Health Survey. 2002; Hacettepe University, TFHP Foundation, UNFPA: Ankara, 239–289.

- A Toros, Z Öztek. Health Services Utilization in Turkey (1992 National Survey): Final Report. 1993; Republic of Turkey MoH: Ankara, 93–95.

- L Akin. Demographic features and some health problems in Turkey. Turkish Journal of Population Studies. 23: 2001; 3–26.

- Law on the Socialization of Health Services, No.224. Official Journal, Assigned No.10705. 1 December 1961, Turkey.

- NH Fişek. Introduction to Public Health. 1983; Cag Printing House: Ankara.

- N Eren, Z Öztek. Management of Health Centers. 5th ed, 1992; Palme: Ankara.

- A Akin. Cultural and psychosocial factors affecting contraceptive use and abortion in two provinces in Turkey. A Mundigo, C Indriso. Abortion in the Developing World. 1999; World Health Organization, Vistaar Publications.

- A Akin. Implementing the ICPD Programme of Action: Turkish experience in sexual and reproductive health. CP Puri, PFA Van Look. Recent Advances, Future Directions. Vol.1: 2001; Indian Society for the Study of Reproduction and Fertility, World Health Organization, New Age International (P) Ltd Publishers. 57–69.

- Turkey Demographic and Health Survey 1998. 1998; Hacettepe University Institute of Population Studies: Macro International Inc, Ankara.

- A Akın, B Doğan, S Mihçiokur. Survey on Causes of Maternal Mortality from the Hospital Records in Turkey. Report submitted to the MoH–MCH/FP General Directorate, Ankara. 2000

- A Akin, MA Biliker, B Doğan, S Mihçiokur. 2001. Maternal mortalities and their causes in Turkey. Aktüel Tıp: A Special Issue on Women's Health. 6(1): 2001; 24–29.

- DB Guciz, A Akin, A Akin. Contraceptive use, attitudes towards contraception and intention for future contraceptive use in Turkey. Results of Further Analysis of 1998 Turkish Demographic and Health Survey. 2002; Hacettepe University, TFHP Foundation, UNFPA. 77–145.

- Health Statistics Yearbook of Turkey 1987–1994. 1997; Republic of Turkey, MoH: Ankara.

- S Tezcan, CE Carpenter-Yaman, NH Fişek. Abortion in Turkey. 1980; Hacettepe University Institute of Community Medicine, No.14: Ankara.

- A Akin, T Enünlü. Induced abortions in Turkey. A Akın. Contraception, Abortion, and Maternal Health Services in Turkey. Results of Further Analysis of 1998 Turkish Demographic and Health Survey. 2002; Hacettepe University: TFHP Foundation, UNFPA, Ankara, 147–175.

- A Akin, SB Ozvaris. Study on the influential factors of sexual and reproductive health of adolescents in the first year students of the two universities in Turkey. Executive Summary. Hacettepe University, Public Health Department, WHO Collaborating Centre on Reproductive Health, Special Programme of Research, Development and Research Training in Human Reproduction, World Health Organization. 2004; Kum Baski Printing House: Ankara.

- Country Health Report 1997. 1997; Republic of Turkey, MoH: Ankara.

- Akin A, Ozvaris SB. Integrating an expanded range of reproductive health services in primary health care: Turkey's experience. Innovations, Institutionalizing Reproductive Health Programmes 1999. 7–8:115–35.

- S Koray. Dynamics of demography and development in Turkey: implications for the potential for migration to Europe. Turkish Journal of Population Studies. 19: 1997; 37–55.

- Situation Analysis of Mothers and Children in Turkey. Government of Turkey, UNICEF Programme Cooperation, Country Programme 1991–1995. 1991; Yenicag Printing House: Ankara, 25–45.

- Records of General Directorate of MCH–FP. 2004; Republic of Turkey, MoH: Ankara.

- Annual Activity Report. 2001. 2003; Republic of Turkey, Ministry of Health, General Directorate of Primary Health Care: Ankara.

- Turkish Legislation on Biddings, No.4734. Official Journal, Assigned 4 January 2002, Turkey.

- G Baltaci. Manpower and Health Problems in 21st Century. New Turkey. 39: 2001; 235–240.

- USAID's Family Planning and Reproductive Health Assistance in Turkey, Annual Report, 1998. US Embassy/Ankara Publication, Ankara.

- National Service Guidelines on Family Planning. 1994; Republic of Turkey, Ministry of Health General Directorate of MCH–FP: Ankara.

- Annual Activity Report 1991. 2003; Republic of Turkey, Ministry of Health, General Directorate of MCH-FP: Ankara.

- Turkish Association for Fighting AIDS. At: 〈http://www.ntvmsnbc.com/news/245928.asp?.cp1=1#BODY. 〉.

- Association to Fight AIDS. At: 〈http://www.aids.org.tr/metinler_eng.tsp?al=sayfayaz&metin=1. 〉.

- Department of Public Health Profile–1993. 1993; Hacettepe University Medical Faculty, Department of Public Health: Ankara.

- Turkey Moving Toward a National Strategy for Family Planning IEC: A Needs Assessment. MoH, US Embassy/Ankara, Johns Hopkins Center for Communication Programs, June 1994.

- Third Country Programme, 2001–2005, Republic of Turkey and UNFPA. At: 〈http://www.unfpa.org.tr. 〉. Accessed 22 July 2004.

- Financial Agreement for the Programme for Reproductive Health in Turkey, Government of Turkey and the European Commission, EUROPEAID/111056/C/SV/TR, 2001.

- A framework for sexual and reproductive health services in Turkey. Prepared for the Programme of Reproductive Health in Turkey in partnership with the European Union. Ankara, June 2004.

- Situation analysis of mothers and children in Turkey, Joint Programme between Government of Republic of Turkey and UNICEF. 1996; Pelin Printing House: Ankara, 172–173.

- Definitions and Indicators in Family Planning, Maternal and Child Health and Reproductive Health. Reproductive, Maternal and Child Health, European Regional Office. 2001; WHO: Copenhagen.

- WHO Division of Reproductive Health (Technical Support). Selecting Reproductive Health Indicators: A Guide for District Managers. WHO/RHT/HRP/97.25. 1997; WHO: Geneva.

- WHO Division of Reproductive Health (Technical Support). Monitoring Reproductive Health: Selecting a Shortlist of National and Global Indicators. WHO/RHT/HRP/97.26. 1997; WHO: Geneva.

- WHO Department of Reproductive Health and Research. Reproductive Health Indicators for Global Monintoring. Report of the 2nd Interagency Meeting, 17–19 July 2000. WHO/RHR/01.19. 2001; WHO: Geneva.

- Strategic Action Plan for the Health of Women in Europe. 2001; Reproductive Health/Pregnancy Programme, Division of Technical Support, EUR/01/5019540: Copenhagen.