Abstract

The advent of democracy in South Africa in 1994 created a unique opportunity for new laws and policies to be passed. Today, a decade later, South African reproductive health policies and the laws that underwrite them are among the most progressive and comprehensive in the world in terms of the recognition that they give to human rights, including sexual and reproductive rights. This paper documents the changes in health policy and services that have occurred, focusing particularly on key areas of sexual and reproductive health: contraception, maternal health, termination of pregnancy, cervical and breast cancer, gender-based and sexual violence, HIV/AIDS and sexually transmitted infections and infertility. Despite important advances, significant changes in women's reproductive health status are difficult to discern, given the relatively short period of time and the multitude of complex factors that influence health, especially inequalities in socio-economic and gender status. Gaps remain in the implementation of reproductive health policies and in service delivery that need to be addressed in order for meaningful improvements in women's reproductive health status to be achieved. Civil society has played a major role in securing these legislative and policy changes, and health activist groups continue to pressure the government to introduce further changes in policy and service delivery, especially in the area of HIV/AIDS.

Résumé

L'avènement de la démocratie en Afrique du Sud en 1994 a permis d'adopter de nouvelles lois et politiques. Aujourd'hui, dix ans après, les politiques sud-africaines en santé génésique et la législation qui les régit sont parmi les plus progressives et complètes du monde dans la reconnaissance qu'elles accordent aux droits de l'homme, y compris aux droits génésiques. Cet article retrace les changements dans les politiques et services de santé, se centrant sur des domaines clés de la santé génésique : contraception, santé maternelle, interruption de grossesse, cancer de l'utérus et du sein, violence sexuelle et contre les femmes, VIH/SIDA et infections sexuellement transmissibles, et stérilité. Malgré des progrès réels, il est difficile de discerner des changements importants dans l'état de santé génésique des femmes, compte tenu de la relative brièveté de la période d'application et de la multitude de facteurs complexes qui influencent la santé, particulièrement les inégalités socio-économiques et sexuelles. Il convient de corriger les lacunes qui demeurent dans l'application des politiques de santé génésique et dans la prestation des services afin d'améliorer sensiblement la santé génésique des femmes. La société civile a joué un rôle majeur pour assurer ces changements législatifs et politiques, et les groupes d'activistes continuent de faire pression sur le Gouvernement pour qu'il introduise d'autres changements dans les politiques et la prestation des services, en particulier dans le domaine du VIH/SIDA.

Resumen

La llegada de la democracia en Sudáfrica en 1994 creó una oportunidad única para que se aprobaran nuevas leyes y polı́ticas. Una década después, las polı́ticas de salud reproductiva de Sudáfrica y las leyes que las rigen figuran entre las más progresistas y amplias del mundo en cuanto al reconocimiento que le otorgan a los derechos humanos, incluı́dos los derechos sexuales y reproductivos. En este artı́culo se documentan los cambios que se han efectuado en las polı́ticas y en los servicios de salud, centrados especialmente en las áreas clave de la salud sexual y reproductiva: la anticoncepción, la salud materna, la interrupción del embarazo, el cáncer cervical y el de mama, la violencia basada en género y la violencia sexual, el VIH/SIDA y las infecciones de transmisión sexual y la infecundidad. A pesar de que se han logrado importantes avances, es difı́cil percibir cambios significativos en el estado de la salud reproductiva de las mujeres, debido al perı́odo de tiempo relativamente corto y a la infinidad de factores complejos que influyen en la salud, en particular las desigualdades en la posición socioeconómica y de género. Aún existen deficiencias en la aplicación de las polı́ticas de salud reproductiva y en la prestación de servicios, las cuales deben suplirse a fin de lograr avances significativos en los aspectos relacionados con la salud reproductiva de las mujeres. La sociedad civil ha desempeñado un papel primordial en garantizar esta reforma de legislación y polı́ticas, y los grupos de activistas en salud continúan ejerciendo presión sobre el gobierno para que se efectúen más cambios en las polı́ticas y en la prestación de servicios, particularmente en los aspectos del VIH/SIDA.

Major transformations have taken place in South Africa over the past decade in health legislation, health policy and the delivery of health services. In this paper, we document changes in reproductive health policy and describe changes in key areas of reproductive health status.

Reproductive health policy and services under apartheid

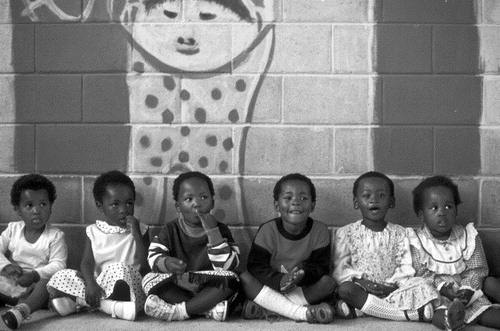

Under apartheid, South African society was racially segregated and extremely discriminatory. Black South Africans were denied political, social, economic and health rights. The public sector health system was fragmented and characterised by geographical and racial inequalities.Footnote* By the mid-1980s, ten state health departments existed as a result of the notorious “homeland” policy. Three separate “own affairs” departments of Health Services and Welfare for whites, coloureds and Indians were established under the Tricameral parliament, which was formed in 1983.Citation1 The greatest proportion of health resources were allocated to the delivery of health care for the white minority in urban areas,Citation2 with emphasis placed on the provision of curative, high technology, hospital-based services in urban centres.Citation1

Before 1994, there were no comprehensive reproductive health policies in South Africa. In keeping with international trends, women's health services consisted mainly of maternal and child health services,Citation3 Citation4 with an emphasis on contraceptive services aimed at limiting population growth. Contraceptive provision had racial undertones, as the South African government sought to control black population growth in particular.Citation5 Long-acting injectable contraceptives were strongly promoted for black women, particularly in rural areas, while the oral contraceptive pill, a more reversible method, was promoted for white women.Citation6 By 1994, there were over 65,000 contraceptive service points in the country; the extensive availability of contraceptive services was in stark contrast to all other primary level health services, including other reproductive health services, which were poorly developed and inaccessible to the vast majority of the population, especially people living in rural areas.Citation7

Maternal health services were characterised by overcrowding, understaffing, and lack of privacy, and women frequently experienced access problems.Citation7 Cervical screening was conducted in an ad hoc manner in public sector services and was primarily available to younger women attending family planning and antenatal services.Citation8 Women with access to private sector health services, mostly white women, enjoyed more regular cervical screening, creating a racial disparity in cervical cancer rates, with black women experiencing much higher rates than white women.Citation9 Termination of pregnancy (TOP) was permitted on extremely restricted grounds. It is estimated that prior to the liberalisation of TOP legislation in 1996, 200,000 illegal abortions occurred annually and were associated with substantial preventable morbidity and mortality.Citation10 Almost all of the 1,000–1,500 legal abortions performed annually during this period were among white women.Citation11 The severity of gender-based violence was not recognised or dealt with effectively,Citation12 and services for sexual violence were fragmented, with no comprehensive plan for collaboration between the relevant government departments. Finally, the apartheid government largely ignored the emerging issue of HIV/AIDS. Hence, in 1994, the new democratic government inherited a deeply divided, fragmented and inequitable health system.

Transition to democracy: changes in reproductive health policy

Opposition and armed struggle against apartheid, combined with mounting international pressure, led to a transitional political period from 1990 until South Africa's first democratic election in 1994. In 1990, the African National Congress (ANC) established a health commission bringing together anti-apartheid health activists and theorists who began to formulate a health plan aimed at transforming the health sector into a single system with an equitable distribution of resources and expanded service delivery.Citation2 Civil society organisations active in gender and women's health research and programmes also lobbied for the creation of locally appropriate reproductive health policies that were in tune with the emerging international emphasis on human rights and gender equity. At the same time, key international conventions, such as the 1994 International Conference on Population and Development (ICPD) in Cairo and the 1995 Fourth World Conference on Women (FWCW) in Beijing, were making explicit links between women's reproductive health, women's rights and socio-economic development, and emphasising a broadened definition of reproductive health.Citation13

Reproductive health legislation and policy: achievements and challenges

As a result of efforts by government and health activism by civil society organisations, many laws and policies affecting reproductive health have been passed in South Africa since 1994 (see Box 1). A women's health conference, hosted in late 1994 by the Women's Health Project at the University of the Witwatersrand, brought together women from across South African society.Citation14 Many of the policy recommendations emanating from this conference were included in the government's reproductive health policies.Citation14 In 1994, the new National Department of Health, in partnership with the World Health Organization and stakeholders from civil society, undertook a rapid assessment of reproductive health services and conducted a national workshop to develop recommendations on research priorities and policy formulation.Citation7 At the same time, the South African government participated in shaping the consensus on reproductive health and rights at the ICPD and FWCW.

In 1994, the Department of Health adopted the Primary Health Care approach as the philosophical and structural orientation of the South African health care system.Citation15 This approach emphasised health as a human right, equity in resource distribution, expanded access, decentralised services aimed at promoting local health needs and community involvement through the district health system, and preventive and promotive health care.Citation2 Free primary-level health services were introduced, targeting women and children. A key goal was to redress past neglect of the health needs of poor, black women.

Laws and policies addressing gender inequity from 1994 on provided an enabling environment for reproductive health reforms, e.g. the new Constitution and Bill of Rights that outlawed discrimination on the basis of sex, gender and sexual orientationCitation16 and international conventions such as the CEDAW. A Joint Monitoring Committee on the Improvement of the Quality of Life and Status of Women was established to oversee and monitor government progress in promoting gender equity.

These changes in law and policy were accompanied by a major restructuring of health programmes and administration. In 1995, a directorate of Mother, Child and Women's Health was established within the National Department of Health whose objectives were to increase women's access to appropriate health services, to ensure that approaches to health service delivery were consistent with the goal of increasing gender equality, and to provide services to women and men that facilitated the achievement of optimal reproductive and sexual health.Citation17 This represented an important step by policymakers, in tune with current international thinking, in acknowledging that women bear a disproportionate burden of reproductive health problems and that gender is an important determinant of health. However, there has been an ongoing tendency within government directorates and programmes to pay limited attention to other women's health problems apart from reproductive health.

Initiatives to address inadequacies in the provision of adolescent sexual and reproductive services have also been introduced. The National Adolescent-Friendly Clinic Initiative (NAFCI) was launched in 1999 by a national NGO, Lovelife, with support from the Department of Health. NAFCI, which is currently being piloted, provides public health service managers and providers with a self-assessment strategy aimed at improving the quality of services delivered to adolescents at primary health care level. NAFCI forms part of a proposed, nationally standardised, adolescent-friendly clinic accreditation.Citation18

Without a doubt, there have been a number of significant achievements, but a number of challenges remain. Weaknesses in the broader public health system have resulted in significant shortcomings in public health sector capacity to plan and institute the new policies and services, and to manage and monitor their implementation.Citation19 The new government has also faced enormous challenges in rationalising the numerous health administrations into a unitary health system, while simultaneously addressing major health problems and health service delivery issues. Delays and difficulties in implementing the district health system have created uncertainty in health service governance, and in the organisational structures through which to route programme and service implementation. Low morale among public sector health care providers makes securing and retaining skilled personnel difficult as well as impacting negatively on effective policy and service implementation.Citation15

Shortages in human and financial resources, coupled with increasing utilisation of the public sector, compromise the delivery and implementation of adequate public sector services, particularly in rural areas.Citation20 A recent study documented a decrease in per capita health care expenditure in the public sector from 1997 to 2003, due primarily to a marked increase in the number of people attending public health services.Citation21 The lack of sufficient resources for public sector health care delivery occurs within a context of competing needs for resource allocation for housing, education and job creation, and by the continued skewed allocation of health resources towards the private health sector. While less than 20% of the South African population has access to private health care, this sector consumes nearly 60% of all health care resources.Citation22 While making health care free has increased overall accessibility, especially for women and children,Citation23 the movement of resources from the secondary and tertiary levels to the primary level has had a negative impact on the availability of certain specialised and hospital-based health care services for the poor.Citation24

Changes in key areas of sexual and reproductive health

Specific legislative and policy advances have occurred in key areas of reproductive health, namely contraception, abortion, maternal health, female cancers, violence and HIV/AIDS, but much remains to be done and certain areas have received little attention to date, such as infertility, reproductive health care for women with HIV and health needs of older women.

Contraception

South Africa's 1998 Population Policy provides a multi-sectoral framework for addressing population issues. This policy represented an important shift, from the previous focus on population control to a focus on the empowerment of women, active involvement of men in reproductive health, and the need for both women and men to make informed reproductive decisions.

The National Contraception Policy (2002) and Service Delivery Guidelines (2004) were developed by expert consensus using both local and international evidence. These documents have been instrumental in identifying problems in contraceptive services, such as limited method choice, provider coercion, overly restrictive approaches to contraceptive initiation, the exclusion of men and lack of services for youth, and by providing a comprehensive framework for contraceptive care.Citation25

Due to past population policy, even before 1994, South Africa had a high contraceptive prevalence compared to other sub-Saharan African countries. Three-quarters of South African women have used a contraceptive method, and 61% of sexually active women currently use a method of contraception.Citation26 The progestogen-only injectable contraceptive is the most common method (comprising 49% of current contraceptive use among sexually active women), followed by the oral contraceptive pill and female sterilisation (both about 20% of current use among sexually active women).Citation26 Footnote*

These high levels of contraceptive use have contributed to a decline in the total fertility rate from 3.3 in 1991 to 2.9 in 1999. Since 1994, in keeping with the primary health care approach, public sector contraceptive services have been integrated into general primary care services. Increased access to contraception when making other health service visits has enhanced continuity of care.Citation26

Despite efforts to expand contraceptive options over the past ten years, however, there has been little change in the available contraceptive method mix, and injectables continue to be used at very high rates.Citation26 While this may reflect user preference, the role of health care providers in influencing contraceptive choice is well-documented. Method choice is frequently limited in the public sector by the opinions and practices of primary care nurses.Citation25 Research continues to show that women are not given adequate information about contraceptive methods, and that women's concerns regarding particular methods are not taken seriously by health service providers.Citation27 Citation28

Barriers in accessing family planning services remain, especially for young women. These include concerns over lack of privacy, inconvenient clinic opening times, and discouragement by clinic staff who disapprove of youth being sexually active.Citation18 This means that many young women initiate contraception only as part of post-natal care after an unintended pregnancy.Citation26 Despite the availability of contraceptive services, South African women continue to experience high rates of teenage and unintended pregnancy. Thirty-five per cent have been pregnant by age 19,Citation26 and up to 53% of pregnancies are either unplanned (36%) or unwanted (17%).Citation26 Thus, greater efforts to improve women's use of effective contraception are required.

In 1998, 22% of sexually active women reported ever using a condom; 8% reported using a condom during last sexual intercourse.Citation26 In 2002, 28.6% of sexually active women reported using a condom at last intercourse.Citation29 Although these data suggest increasing condom use among women, levels of use remain unacceptably low. High levels of HIV and other sexually transmitted infections (STIs) mean that many South African women require protection against both pregnancy and infection. Only a small minority of sexually active women in South Africa are simultaneously protected against STI and pregnancy during sexual intercourse by using a condom and an even smaller minority (6.3–7.5%) use a condom with another contraceptive method to achieve dual protection.Citation30 Citation31 In this context, the promotion of condoms as part of the contraceptive method mix and for dual protection requires greater attention, as does the development of other female-initiated methods, such as microbicides. While the effectiveness of microbicides in preventing HIV is still unknown, several clinical trials are underway in South Africa. Nationally, the only barrier method available to public sector clients is the male condom; the female condom is only available at limited sites or through the private sector, where high prices restrict accessibility.

Emergency contraception is available at public sector health clinics. However, use is very low, due primarily to lack of knowledge of the method on the part of potential users.Citation32

Maternal health

The introduction of free health care for pregnant women in 1994 improved women's access to appropriate care during pregnancy. The designation of maternal death as a notifiable condition in 1997 and the appointment of a National Committee for Confidential Enquiries into Maternal Deaths have enabled the quantification of maternal mortality and provided a mechanism for continued surveillance. The Confidential Enquiry and health service-based maternal mortality surveillance provide critical information on medical causes, so that interventions can target these causes. However, they do not capture the burden of maternal mortality attributable to non-medical causes, such as gender-related barriers in access to medical care.

Maternal mortality statistics before and after 1994 cannot be validly compared as, prior to 1994, data were typically collected only in urban areas and among women giving birth in maternity homes, leading to substantial underestimates of maternal mortality. In certain areas of the country, there has been a steady decrease in maternal mortality over the past half-century, with the rate halving between 1953 and 2002.Citation33 The national maternal mortality rate is currently estimated at 150 per 100,000 live births,Citation26 but this national average belies substantial regional variation.Citation26 The HIV/AIDS pandemic threatens to undo the considerable gains made in the area of pregnancy-related mortality. The national enquiry into maternal deaths in South Africa found AIDS to be the cause of 17% of maternal deaths in the years 1999–2001, and this is believed to be a considerable underestimate, as the HIV status of women was known only in just over a third of cases.Citation34 In antenatal, delivery and post-natal services, programmes for the prevention of mother-to-child transmission of HIV (PMTCT) have been introduced, but little attention has been given to dealing with the consequences of HIV infection for women themselves.

Termination of pregnancy

Termination of pregnancy is an area of women's reproductive health where major changes in legislation, policy and the delivery of services have resulted in measurable improvements in women's health status. The 1996 Choice on Termination of Pregnancy Act allows for termination on request for pregnancies of 12 weeks or less gestation, provided by a certified midwife or doctor. Pregnancies of 13–20 weeks may be terminated when continuation of the pregnancy poses a risk to the woman's social, economic or psychological well-being.Citation11

This act was ground-breaking in its intention to promote broader access to free TOP services, particularly for poor black women. There have been two unsuccessful legal challenges to the Act. The maintenance of the law in its current form, despite substantial pressure placed on the government to change it, speaks to South Africa's commitment to reproductive rights at a time when reproductive rights are being threatened in a number of countries around the world. Civil society organisations played a pivotal role in securing change in the abortion law. In particular, the Reproductive Rights Alliance was instrumental in initiating the legislation and steering it through a lengthy national consultative process; they continue to monitor implementation of the legislation and the delivery of services.

Prior to the passing of the law, 34% of incomplete abortions admitted to public hospitals annually were estimated to have resulted from unsafe abortions.Citation35 Two years after the passing of the new Act, the number of women with serious abortion- related morbidity had almost halved (9.5% in 1999 compared to 16.5% in 1994) and the vast majority (91%) had no signs of infection on admission. Maternal mortality from unsafe abortions has also decreased.Citation35

A commitment by reproductive health programme managers, some facility managers and a small cadre of health service providers across the country to render effective service delivery have increased women's access to services in both the public and private sectors. The provision of first trimester abortions by certified midwives has also increased service availability.Citation35 Although many health facilities designated to provide TOP have not been doing so, there has been recent progress with an increase from 33% of designated facilities functioning in 2001 to 48% in 2003.Citation36 The number of legal abortions performed annually in South Africa has steadily increased, from 29,375 in 1997 to 53,510 in 2001.Citation35

A great challenge stems from the shortage of health care providers willing and trained to provide abortions. Access is further hindered by providers asserting conscientious objection. In spite of the legal obligation to refer to a willing provider, many providers try to discourage women from having an abortion, presenting a fundamental barrier to care.Citation37 Values clarification workshops designed to promote more tolerant attitudes by service providers have taken place,Citation35 and services are currently delivered in some places by roving teams of health service providers to increase access for women in settings where the providers are unwilling to provide the service.

Further initiatives by government to broaden access to TOP services are contained in the Choice on Termination of Pregnancy Amendment Act of 2003, recently approved by Parliament. The amendment allows any health facility with a 24-hour maternity service to offer first trimester abortion services, without the ministerial permission that is currently required. It additionally allows all registered nurses who have completed the prescribed TOP training course, not only midwives, to provide first trimester terminations.Citation38 Also, mifepristone, for use in medical abortions up to eight weeks of pregnancy has been approved by the South African Medicines Control Council, and the introduction of medical abortion in the public health sector is under consideration by the Department of Health.

Cervical and breast cancer

Cancer of the cervix is a major preventable cause of morbidity and mortality in South Africa, and is the most common cancer in black women, who have a risk of developing cervical cancer twice that of Asian women, and 2.4 times that of white and coloured women.Citation39 The life-time risk for cervical cancer was 1:29 for the period 1996–97Citation39 compared with 1:41 in 1993–95.Citation9 Recently, the Department of Health has identified the prevention of cervical cancer as a national priority, and policy changes have occurred, culminating in the implementation of pilot programmes to inform the national roll-out of cervical screening services. In 2000, National Guidelines for a Cervical Screening Programme were developed based on the best available evidence on strategies for low-resource settings. The guidelines call for three free Pap smears in a lifetime, commencing after the age of 30, with ten-year intervals in between.Citation40 The goal of the programme is to screen at least 70% of women in the target group nationally, within ten years of implementation. Theoretically this could decrease the incidence of cervical cancer by more than 60%.Citation40

Key challenges for effective implementation of the screening programme relate to the consolidation of the district health system and the provision of coordinated clinical, laboratory and referral services. Integration of cervical screening into other women's health services at primary health level is essential, and health care workers need to be trained and motivated to deliver effective care.

Breast cancer is the most common cancer for Asian, white and coloured women in South Africa. The lifetime risk in 1997 was 1:13 for Asian women, 1:16 for white and coloured women combined, and 1:57 for black women.Citation39 The lifetime risk of developing breast cancer for South African women overall was 1:31 in 1996–97Citation39 compared to 1:39 in 1993–95.Citation9 Little attention has been given to measures to reduce breast cancer among women in South Africa. Screening by mammography is not available in the public sector due to the cost.

Gender-based and sexual violence

Reliable data on gender-based violence in South Africa prior to 1994 are unavailable; however, rates are not thought to have decreased in the past decade. In 1998, a nationally representative study estimated ever-physical abuse by an intimate partner at 12%.Citation26 A three-province study on intimate partner abuse conducted in 1999 found a much higher prevalence of ever-physical abuse (27%, 28% and 19% for Eastern Cape, Mpumalanga and Northern provinces, respectively).Citation41

Legislative and policy reforms to address gender-based violence have taken place since 1994, driven primarily by women's organisations.Citation42 The Domestic Violence Act, passed in 1998, is regarded as one of the most progressive in the world.Citation12 It recognises the unacceptable levels of domestic violence, provides for legal protection orders in any domestic relationship, and expands the definition of domestic violence to include a wide range of types of abuse.Citation2 Citation12 However, while the total number of protection orders being sought by women against abuse has increased, only half of these were for protection against an intimate partner, a major source of abuse for women (Personal communication, N Abrahams, March 2004). Furthermore, the application process was found to be unwieldy and poorly understood by women; there has been inadequate health service provider training; and implementation has been hampered by the under-resourced legal system.Citation12 Citation43 Efforts are being made to address some of these problems. A South African Gender Based Violence and Health Initiative was formed in 2000 to encourage recognition of violence against women as a problem, train health care providers and conduct research to help to develop policy on gender-based violence.Citation43 Citation44

Although many rapes are not reported, South Africa has the highest number of reported rape cases per female population in the world (240/100,000 women in 1997).Citation45 Representative community-based surveys have estimated 2,070 rapes or attempted rapes per 100,000 women per year among 17–48 year olds and forced sexual initiation of almost a third of adolescent girls, making rape a major threat to public health.Citation12 Citation45 Citation46 Rape legislation is currently undergoing review, with a new Bill of Sexual Offences being formulated that will define rape more broadly and introduce stricter sentencing for offenders.

Under civil society pressure to address links between sexual violence and HIV, the government approved the provision of HIV post-exposure prophylaxis (PEP) to rape survivors in public sector facilities in 2002, and the Department of Health developed national guidelines on the management of HIV and STI transmission in cases of sexual violence that include PEP provision.Citation44 Two important initiatives to provide PEP through public sector services have been implemented: one by an NGO working with rape survivors at rape care centres in two public hospitals in the rural province of Mpumalanga and the other by provincial health service providers at two public hospitals in Cape Town. Challenges in translating the PEP policy into effective service provision across South Africa include unevenness in political support and under-resourced local health systems.Citation47

Until 1996, sexual assault services were provided only by district surgeons employed by the state. Today, all public sector doctors and private practitioners provide sexual assault services, thus, improving accessibility. However, a recent national study has highlighted several problems with sexual assault service delivery: lack of coordination between the health, police and legal sectors; lack of standardised clinical protocols; inadequate training of health care providers; problems in referral for counselling; lack of privacy; and lengthy waiting times at services. To improve quality of care and ensure appropriate collection of evidence for the prosecution of offenders, the establishment of designated providers and facilities for the delivery of sexual assault services has been recommended. The Department of Health is currently reviewing national guidelines on the management of survivors of sexual offences and has produced a draft protocol to provide a more comprehensive management and care package.Citation44 Citation45 Some local initiatives to improve health services and standardise care have been initiated (Personal communication, Prof Lynn Denny, January 2004). Parallel initiatives are underway within the criminal justice system to train magistrates and judges on the substantive law and procedural aspects of rape trials and on the proposed amendments to the forthcoming Sexual Offences Law (Personal communication, Lillian Artz, Director, Gender, Health and Justice Research Unit, University of Cape Town, July 2004). These initiatives may serve as models for other areas of the country.

In spite of these gains, if the high levels of violence against women are to decrease, preventive interventions are urgently needed to address the societal values, attitudes and beliefs that give rise to such violence and abusive behaviour.

HIV/AIDS and sexually transmitted infections

South Africa currently faces one of the worst HIV/AIDS epidemics in the world. In the past 15 years, surveillance data show an increase in HIV prevalence in the antenatal population from less than 1% in 1990 to almost 27% in 2002.Citation48 In 1995–96, 10% of deaths among 15–49 year olds were due to AIDS; in 2000 this statistic had risen to 40%.Citation49 The epidemic features distinctive age and gender distributions with young women at greatest risk, and overall proportionally more women affected than men.Citation50 Citation51 It is estimated that in youth aged 15–24, about four women are infected for every man.Citation49 Women's greater vulnerability to HIV infection, although partly biological, is strongly driven by the gender inequalities that pervade South African society.Citation52 Citation53 Citation54 Women's lower social and economic status simultaneously increases their risk of exposure to HIV by impeding their ability to refuse sex, decreases their ability to negotiate and implement protective strategies, such as barrier method use during sex, and makes it difficult for women to safely discuss and disclose their HIV status without risk of abandonment or violence.Citation54 Citation55 Women's economic dependence on men also diminishes their power to negotiate safer sex for fear of financial reprisal, and sometimes forces them to engage in transactional or commercial sex to maintain their livelihoods.Citation54 Citation56 In addition, cultural assumptions such as men's “right” to engage in sexual relations with multiple partners mean that sexual intercourse, even with spouses and intimate partners, carries high levels of risk for women.Citation54 Citation55 Citation56 Citation57 Citation58 Women's vulnerability is also exacerbated by the threat of gender-based violence and sexual assault.Citation59 Citation60 Citation61

In addition to the direct effects of HIV infection on women's health, the epidemic is disproportionately affecting women and girls in their gendered role as care-givers within families and communitiesCitation62, in that they are bearing the greatest burden of caring for those with AIDS-related illnesses. This has implications for the time women are able to spend on income-generating activities or education and potentially creates greater levels of poverty and increased economic dependence among them.

There are an estimated 6 million people living with HIV at present, or approximately one in every seven South Africans.Citation49 The best available modelling efforts suggest that the epidemic is likely to continue to grow over the next few years unless effective interventions are introduced.Citation63 Citation64 Citation65 The importance of gendered differences in HIV transmission, the management of AIDS-related illnesses, and the health-seeking behaviour of HIV-infected individuals requires greater recognition if progress is to be made in halting the spread of HIV.

STIs are an important cause of reproductive morbidity, especially for women.Citation26 Citation66 Citation67 Citation68 An estimated two million people are treated for STIs at public sector primary care facilities annually in South Africa.Citation69 STIs are a well-known risk factor for HIV infectionCitation70 and have fuelled the spread of HIV.Citation67 Citation71 Government policy has been to integrate STI services into primary care, and in line with WHO guidelines, has adopted a syndromic approach to diagnosis and management, treating people immediately on the basis of their symptoms and a clinical examination, rather than having them return for laboratory test results. This potentially increases treatment and cure rates.Citation72

HIV is a tremendous threat to reproductive health status. It also affects other areas such as maternal health, fertility, contraceptive needs and gender-based violence,Citation60 and both maternal mortalityCitation73 and cervical cancerCitation74 Citation75 rates are increasing as a result of HIV/AIDS. While there has been substantial attention given to the delivery of antiretroviral therapy, little attention has been given to meeting the reproductive health needs of those with HIV. How best to deliver this care is a critical question facing policymakers and health service providers.

Over the past 10 years, the South African government's policy on HIV/AIDS has been ambiguous at best, often imparting confusing and contradictory messages to health care providers and the public. Government action has been stymied by ideological differences within the government itself, with the South African President and Minister of Health casting doubt on a causal link between HIV and AIDS. Until late 2003, the government's strategic plan for HIV/AIDS focused exclusively on prevention via condom promotion, voluntary testing and counselling, and treatment of STIs and opportunistic infections.Citation76 There was no AIDS treatment policy, or plans to implement one. This exclusive focus on prevention was at odds with international thinking and the opinions of ordinary South Africans. In 2002, the United Nations stated that treatment and care were fundamental to HIV prevention.Citation77 In a recent nationally representative survey of South African adults, 76% viewed HIV/AIDS as a serious threat to democracy in the country; 28% reported having a close friend or relative who had died of AIDS; 55% disapproved of the way the government was handling HIV/AIDS; and 58% said that the government was doing too little about treatment.Citation78 In late 2003, the government approved a plan to implement public sector antiretroviral treatment (ARV) for people with AIDS, proposing to have at least one treatment site in every local municipality within five years.

Civil society organisations, particularly the Treatment Action Campaign (TAC), have played a critical role in pressuring the government to act. In 2002, TAC forced the government through a legal challenge to implement prevention of mother-to-child transmission programmes nationally, and conducted an active social mobilisation campaign, including civil disobedience, for the introduction of public sector ARV treatment.

At community level, stigmatisation of HIV-infected individuals has discouraged testing and disclosure.Citation79 Encouragingly, non-governmental organisations providing community-based support and care have been instrumental in encouraging testing and disclosure, leading to decreases in stigma in some communities.Citation80 Cultural and social beliefs around HIV and STI transmission, gender inequality,Citation81 Citation82 and resistance to condom useCitation31 Citation53 have limited prevention efforts. The ABC (abstain, be faithful or use condoms) approach, and the government's emphasis on “safe and healthy sexual behaviours”Citation83 assume that individuals have the power to implement self-protective behaviours. This must be questioned in this highly unequal society, in which these self-protective behaviours are frequently not in the control of women and girls.

ARV availability will improve the health of South African women by increasing life expectancy and improving health and quality of life. However, ARVs alone cannot succeed; they must be accompanied by social and structural interventions aimed at improving the status of women in South African society.

Infertility

There are no reliable prevalence figures on infertility in South Africa, but it is estimated that 15–20% of couples report difficulties in conception.Citation84 A high proportion of infertility is a consequence of untreated STIs, which to a large degree are preventable through safe sex practices, early detection and treatment.Citation68 Citation84 Infertility services in the public health sector are only available at a limited number of tertiary hospitals. Assisted conception services are available in the private sector but are prohibitively expensive. Because of the importance placed on having children, the social stigma, isolation, and domestic violence that may be experienced by women as the result of involuntary childlessness,Citation85 Citation86 infertility requires attention. While some local initiatives exist to improve access to and quality of infertility services, there has been an absence of policy and service delivery change.

Older women

Few data are available on the reproductive health status and needs of older women, other than in the areas of cervical and breast cancer. There are no accurate statistics on the burden of HIV/AIDS in older South Africans, and there has been very little research conducted on menopause, especially research that explores the diverse meanings and experiences of menopause for women.Citation87

Involving men in reproductive health

Historically, reproductive health advocacy efforts and services have tended to exclude men. However, this is rapidly changing both internationally and in South Africa. The ICPD in 1994 and the 1995 FWCW recognised the importance of including men in sexual and reproductive health for several reasons: men themselves have sexual and reproductive health needs; women's health cannot be improved without men's involvement, particularly in the areas of HIV/AIDS and contraception; and without men's involvement, gender equality cannot be achieved. Current South African reproductive health policies are explicit in encouraging men's involvement.Citation25 A recent qualitative study of microbicide acceptability has shown that the importance of male involvement in reproductive health is recognised at the community level: women, men and health care providers interviewed in this study all stated that male partner involvement and communication within sexual relationships will be critical to the successful introduction of this new technology.Citation88 Identifying practical ways to include men in reproductive health is a great challenge, as is re-orientating reproductive health services to accommodate male involvement. The Planned Parenthood Association of South Africa's Men as Partners Programme is currently tackling this issue through outreach and training workshops.Citation89 The Sexual Rights Campaign,Footnote* a joint effort of a broad range of stakeholders, has embarked on a mass mobilisation strategy to raise awareness about sexual rights among men and women. The campaign is a direct response to the escalating incidence of HIV infection and of violence against women. Sexuality education awareness programmes are directed at youth, particularly young men.Citation90

Conclusion

The positive effects on all spheres of life of a new, progressive dispensation in governance, including health, should not be minimised, especially in a context where freedom, democracy and respect for human rights were previously denied. The advent of democracy in South Africa created a unique opportunity for numerous new laws and policies to be passed, including many within the sphere of reproductive health. A long tradition of political activism, coupled with the flurry of legislative activity that characterised the early years of South Africa's democratic transformation, enabled many women's health groups and other civil society organisations to directly influence policy formulation. This has resulted in the development and adoption of some of the most comprehensive and progressive reproductive health policies in the world.

However, legislative and policy advances in reproductive health have not necessarily been followed by successful implementation and improvements in the delivery of health services. A lack of implementation strategy, planning and clearly expressed time frames combined with inadequate capacity for implementation have undermined many of the intended positive effects of these initiatives. Effective implementation has been hampered by general weaknesses in the public health system stemming from lack of financial and human resources and the legacy of racial and geographical inequalities in health care delivery. Some barriers are specific to particular areas of reproductive health, such as the lack of health care providers willing to perform abortions.

Hence, with the exception of a decrease in morbidity and mortality from unsafe abortion, it is difficult to discern major improvements in women's health status in South Africa since 1994 so far. It is important to recognise, however, that even with the best efforts of the government, significant improvements in health status would be difficult to observe in a ten-year period. The health status of the population as a whole, and of women in particular, has been severely compromised by the HIV/AIDS epidemic, the escalation of which coincided with South Africa's first decade of democracy.

Currently, some national reproductive health surveillance is being carried out by government so that progress can be accurately monitored, i.e. regarding maternal deaths and progress in delivery of safe abortion services. There is a need for further development of indicators to measure progress in these and other areas of reproductive health.

In addition to health sector constraints and the impact of HIV/AIDS, the broader socio-economic context continues to have a profound effect on the health status of South Africans, particularly of women, who bear the greatest burden of poverty. Despite socio-economic development over the last decade, the distribution of wealth and income in South Africa remains the second most unequal in the world.Citation91 Levels of unemployment exceed 40% nationallyCitation92 and marked inequalities in socio-economic status based on race and gender remain.Citation93 These problems will need to be overcome before marked improvements in women's health status can be observed.

One of the most encouraging occurrences during the first ten years of democracy in South Africa has been the significant role played by civil society in affecting legislative and policy change. While civil society activism used to be focused on opposing apartheid, the tradition of opposition has served to facilitate change within a democratic system. The influence of civil society has been particularly important in three areas of reproductive health legislation and policy: abortion, gender-based violence, and PMTCT and ARV treatment for HIV. Civil society organisations have been able to play less of a role in ensuring that laws and policies are effectively implemented and in monitoring and evaluating their impact. The reasons for this need further investigation since civil society organisations can and should play a central role in holding government accountable for the faster and more successful translation of its laws and policies into improvements in the health status of all South Africans. Overcoming barriers to ongoing advocacy efforts and continued strengthening of democracy in South Africa, both within and outside of government, is critical for ensuring that civil society is able to play this important role.

Notes

* The use of colour terms is not intended to denote differences due to biology or legitimise a racial classification system. Under the apartheid government all South Africans were classified according to skin colour and this has created a legacy of severe disparities in all spheres of life, including in health. The terms are used here to acknowledge this impact and track progress in redressing past inequality based on colour.

* These percentages on type of method use have been calculated from the figures provided in the South African Demographic and Health Survey.Citation26

* This campaign includes the following organisations: Women's Health Project at the University of the Witwatersrand, Joint Enrichment Project, National Association of People Living with AIDS, National AIDS Convention of South Africa, National Network of Violence against Women, Planned Parenthood Association, YMCA and community-based organisations throughout South Africa.

References

- HC Van Rensburg, D Harrison. History of Health Policy. Health Systems Trust. South African Health Review 1995. 1995; Health Systems Trust: Durban.

- B Klugman, M Stevens, A Van den Heever. Sexual and Reproductive Rights, Health Policies and Programming in South Africa 1994–1998. 1998; Women's Health Project: Johannesburg.

- MA Koblinsky, OMR Campbell, SD Harlow. Mother and more: a broader perspective on women's health. M Koblinsky, J Timyan, J Gay. The Health of Women. A Global Perspective. 1993; Westview Press: Boulder, 33–62.

- M Holloway. Trends in women's health: a global view. Scientific American. 1994; 67–73.

- B Klugman. Balancing means and ends: population policy in South Africa. Reproductive Health Matters. 1(1): 1993; 44–57.

- M Gready, B Klugman, H Rees. South African women's experiences of contraception and contraceptive services. TKS Ravindran, M Berer, J Cottingham. Beyond Acceptability: Users' Perspectives on Contraception. 1997; Reproductive Health Matters for WHO: London, 23–35.

- Rees H. Background document prepared for the Special Programme of Research, Development and Research Training in Human Reproduction, WHO. Johannesburg, 1994.

- M Hoffman, D Cooper, H Carrara. Limited Pap screening associated with reduced risk of cervical cancer in South Africa. International Journal of Epidemiology. 32: 2003; 573–577.

- F Sitas, J Madhoo, J Wessie. Incidence of histologically diagnosed cancer in South Africa 1993– 1995. 1998; Johannesburg, National Cancer Registry of South Africa, South African Institute of Medical Research.

- B Klugman, SJ Varkey. From policy development to policy implementation: the South African Choice on Termination of Pregnancy Act. B Klugman, D Budlender. Advocating for Abortion Access. Eleven Country Studies. 2001; Witwatersrand University Press: Johannesburg, 251–282.

- H de Pinho, M Hoffman. Termination of pregnancy–understanding the new Act. Continuing Medical Education. 16(8): 1998; 786–790.

- P Parenzee, L Artz, K Moult. Monitoring the implementation of the Domestic Violence Act. First Research Report 2000–2001. 2001; University of Cape Town: Cape Town.

- United Nations September Annex: Draft Final Document of the United Nations Conference on Population and Development. 1994; United Nations: Cairo.

- B Klugman, M Stevens, K Arends. Developing women's health policy in South Africa from the grassroots. Reproductive Health Matters. 3(6): 1995; 122–131.

- Health Systems Trust. South African Health Review 2000. 2000; The Press Gang: Durban.

- Centre for Reproductive Law and Policy, Women's Health Project. Women's Reproductive Rights in South Africa: A Shadow Report. Prepared for the Nineteenth Session of CEDAW. 1998

- National Progressive Primary Health Care Network. Phila Summary Brief. White Paper for Transformation of the Health System in South Africa. Chapter 8: Maternal, Child and Women's Health. 1997; NPPHCN/PHILA: Gatesville.

- K Dickson-Tetteh, A Pettifor, W Moleko. Working with public sector clinics to provide adolescent-friendly services in South Africa. Reproductive Health Matters. 10(17): 2001; 160–169.

- S Fonn, M Xaba, KS Tint. Reproductive health services in South Africa: from rhetoric to implementation. Reproductive Health Matters. 6(11): 1998; 22–32.

- D McIntyre, B Klugman. The human face of decentralisation and integration of health services: experiences from South Africa. Reproductive Health Matters. 11(21): 2003; 108–119.

- Essential Health Care for all South Africans. 2004; National Department of Health: Pretoria.

- J Doherty, S Thomas, D Muirhead. Health care financing and expenditure in the post-apartheid era. Health Systems Trust. South African Health Review. 2002; Health Systems Trust, Henry J Kaiser Family Foundation: Durban, 13–40.

- D McCoy. Free Health Care for Pregnant Women and Children Under Six in South Africa. An Impact Assessment. 1996; Child Health Unit, Health Systems Trust: Durban.

- SR Benatar. Health care reform and the crisis of HIV and AIDS in South Africa. New England Journal of Medicine. 351(1): 2004; 81–92.

- Department of Health, Republic of South Africa. National Framework and Guidelines for Contraceptive Services. 2002; Department of Health: Pretoria.

- Department of Health, Republic of South Africa. South African Demographic and Health Survey. 2001; Department of Health: Pretoria.

- S Magwaza, D Cooper. An Evaluation of the Community Based Distribution (CBD) of Contraceptives Programme in Khayelitsha, Cape Town. Qualitative Research: An Operational Report. 1999; University of Cape Town: Cape Town.

- D Cooper, A Marks. Mid-term Review of the Reproductive and Social Development Interventions. 2001; University of Cape Town: Cape Town.

- The Human Sciences Research Council. Nelson Mandela/HSRC Study of HIV/AIDS. South African National HIV Prevalence, Behavioural Risks and Mass Media. Household Survey 2002. 2002; Human Sciences Research Council: Pretoria.

- C Morroni, J Smit, L McFadyen. Dual protection against sexually transmitted infections and pregnancy in South Africa. African Journal of Reproductive Health. 7(2): 2003; 13–19.

- I Kleinschmidt, BN Maggwa, J Smit. Dual protection in sexually active women. South African Medical Journal. 93(11): 2003; 854–857.

- J Smit, L McFayden, M Beksinska. Emergency contraception in South Africa: knowledge attitudes and use among public sector primary health care clients. Contraception. 64(6): 2001; 333–337.

- S Fawcus, H de Groot. Fifty year audit of maternal mortality in the Peninsula Maternal and Neonatal Service (1953–2002). Presentation to Workshop on Gender and HIV, University of Cape Town. 2003

- J McIntyre. Mothers infected with HIV. British Medical Bulletin. 67: 2003; 127–135.

- Reproductive Rights Alliance. Five year review of the implementation of the Choice on Termination of Pregnancy Act, 92 of 1996. 2002; Progress Press: Johannesburg.

- Government Communications, Republic of South Africa. South Africa Yearbook 2003/04. 2004; STE Publishers: Johannesburg.

- KE Dickson, RK Jewkes, H Brown. Abortion service provision in South Africa three years after liberalisation of the law. Studies in Family Planning. 34(4): 2003; 277–284.

- Republic of South Africa. The Choice on Termination of Pregnancy Amendment Bill, 2003. Government Gazette Notice No. 1388 of 2003, 19 May 2003. At: 〈http://www.info.gov.za/gazette/bills/2003/24869b.pdf. 〉. Accessed 6 August 2004.

- M Mqoqi, P Kellet, J Madhoo. Incidence of histologically diagnosed cancer in South Africa 1996–1997. National Cancer Registry of South Africa. 2003; National Health Laboratory Service: Johannesburg.

- Department of Health, Republic of South Africa. National Guideline for Cervical Cancer Screening Programme. 2002; Department of Health: Pretoria.

- R Jewkes, L Penn-Kekana, J Levin. Prevalence of emotional, physical and sexual abuse of women in three South African provinces. South African Medical Journal. 91(5): 2001; 421–428.

- S Usdin, N Christofides, L Malepe. The value of advocacy in promoting social change: implementing the new domestic violence act in South Africa. Reproductive Health Matters. 8(16): 2000; 55–65.

- R Jewkes, T Jacobs, L Penn-Kekana. Developing an appropriate health sector response to gender-based violence. Report of a workshop jointly hosted by the National Department of Health and South African Gender Based Violence and Health Initiative. Pretoria, 26-27 March. 2001

- N Abrahams, LJ Martin, L Vetten. An overview of gender-based violence in South Africa and South African responses. S Suffla, A van Niekerk, N Duncan. Crime, Violence and Injury Prevention in South Africa: Developments and Challenges. 2004; Medical Research Council-University of South Africa, Crime Violence and Injury Lead Programme: Tygerberg, 40–64.

- N Christofides, N Webster, R Jewkes. The State of Sexual Assault Services: Findings from a Situational Analysis of Services. 2003; Medical Research Council of South Africa: Pretoria.

- R Jewkes, N Abrahams. The epidemiology of rape and sexual coercion in South Africa: an overview. Social Science and Medicine. 55(7): 2002; 1231–1244.

- JC Kim, LJ Martin, L Denny. Rape and HIV post-exposure prophylaxis: addressing the dual epidemics in South Africa. Reproductive Health Matters. 11(22): 2003; 101–112.

- Department of Health, Republic of South Africa. Summary Report. National HIV and Syphilis Antenatal Seroprevalence Survey in South Africa, 2002. 2003; Directorate of Health Systems Research, Research Coordination and Epidemiology: Pretoria.

- R Dorrington, D Bradshaw, D Budlender. HIV/AIDS profile for the provinces of South Africa: Indicators for 2002. 2002; Centre for Actuarial Research, University of Cape Town, Actuarial Society of South Africa, Burden of Disease Research Unit, South African Medical Research Council: Cape Town.

- Q Abdool Karim, SS Abdool Karim. South Africa: host to a new and emerging HIV epidemic. Sexually Transmitted Infections. 75(3): 1999; 139–140.

- AIDS Epidemic Update December 2003. UNAIDS/03. 39 E. Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS) and World Health Organization. 2003; UNAIDS: Geneva.

- RA Royce, A Sena, W Cates Jr Sexual transmission of HIV. New England Journal of Medicine. 10;336(15): 1997; 1072–1078.

- TR Moench, T Chipato, NS Padian. Preventing disease by protecting the cervix: the unexplored promise of internal vaginal barrier devices. AIDS. 15(13): 2001; 1595–1602.

- QA Karim, SS Karim, K Soldan. Reducing the risk of HIV infection among South African sex workers: socioeconomic and gender barriers. American Journal of Public Health. 85(11): 1995; 1521–1525.

- S Maman, J Mbwambo, NM Hogan. Women's barriers to HIV-1 testing and disclosure: challenges for HIV-1 voluntary counselling and testing. AIDS Care. 13(5): 2001; 595–603.

- GR Gupta, E Weiss, D Whelan. Male–female inequalities result in submission to high-risk sex in many societies. Special report: women and HIV. AIDS Analysis Africa. 5(4): 1995; 8–9.

- LL Heise, C Elias. Transforming AIDS prevention to meet women's needs: a focus on developing countries. Social Science and Medicine. 40(7): 1995; 931–943.

- CA Varga. Sexual decision-making and negotiation in the midst of AIDS: youth in Kwazulu-Natal, South Africa. Health Transition Review. 7(and Suppl.3): 1997; 45–67.

- K Wood. An ethnography of sexual health and violence among township youth in South Africa. 2002; London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine: London, 279.

- KL Dunkle, RK Jewkes, HC Brown. Gender-based violence, relationship power, and risk of HIV infection in women attending antenatal clinics in South Africa. Lancet. 363(9419): 2004; 1415–1421.

- S Maman, J Campbell, MD Sweat. The intersections of HIV and violence: directions for future research and interventions. Social Science and Medicine. 50(4): 2000; 459–478.

- L Doyal. What Makes Women Sick. Gender and the Political Economy of Health. 1995; Macmillan Press: London, 40–41.

- Q Abdool-Karim, SS Abdool-Karim. The evolving HIV epidemic in South Africa. International Journal of Epidemiology. 31(1): 2002; 37–40.

- R Dorrington, D Bourne, D Bradshaw. The impact of HIV/AIDS on adult mortality in South Africa. 2001; South African Medical Research Council: Cape Town.

- D Bradshaw, R Laubscher, R Dorrington. Unabated rise in the number of adult deaths in South Africa. At: 〈www.mrc.ac.za/bod/bod.htm. 〉. Accessed 31 March 2004.

- M Colvin. Sexually transmitted infections in southern Africa: a public health crisis. South African Journal of Science. 22: 2000; 335–339.

- D Wilkinson, SS Abdool Karim, A Harrison. Unrecognized sexually transmitted infections in rural South African women: a hidden epidemic. Bulletin of World Health Organization. 77(1): 1999; 22–28.

- W Cates, TMM Farley, PJ Rowe. Worldwide patterns of infertility: is Africa different?. Lancet. 2: 1985; 596–598.

- A Ramkisson, I Kleinschmidt, M Bekinska. A National Baseline Assessment of Sexually Transmitted Infection and HIV Services in South African Public Sector Health Facilities 2002/3. 2004; Reproductive Health Research Unit, University of Witwatersrand: Johannesburg.

- DT Fleming, JN Wasserheit. From epidemiologic synergy to public health policy and practice: the contribution of other sexually transmitted diseases to sexual transmission of HIV infection. Sexually Transmitted Infections. 75(1): 1999; 3–17.

- M Colvin, SS Abdool Karim, C Connolly. HIV infection and asymptomatic sexually transmitted diseases in a rural South African community. International Journal of STD & AIDS. 9: 1998; 548–550.

- D Coetzee, R Ballard. Controlling the epidemic of sexually transmitted diseases in South Africa: the role of syndromic management. Continuing Medical Education. 14(6): 1996; 819–826.

- Department of Health, Republic of South Africa. Saving Mothers. Report on Confidential Enquiries into Maternal Deaths in South Africa. 1999; Department of Health: Pretoria.

- F Sitas, R Pacella-Norman, H Carrara. The spectrum of HIV-1 related cancers in South Africa. International Journal of Cancer. 88(3): 2000; 489–492.

- M Moodley, J Moodley, I Kleinschmidt. Invasive cervical cancer and human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection: a South African perspective. International Journal of Gynecology and Cancer. 11(3): 2001; 194–197.

- Department of Health, Republic of South Africa. HIV/AIDS/STD strategic plan for South Africa, 2000–2005. 2000; Department of Health: Pretoria.

- United Nations. 2002. UNAIDS Report on the Global HIV/AIDS epidemic, 2002. At: 〈http://www.unaids.org/barcelona/presskit/report.html〉. Accessed 28 February 2004.

- Henry J Kaiser Family Foundation. Washington Post, Harvard University. Survey of South Africans at Ten Years of Democracy. 2004; Henry J Kaiser Family Foundation: Washington DC.

- A Medley, C Garcia-Moreno, S McGill. Rates, barriers and outcomes of HIV serostatus disclosure among women in developing countries: implications for prevention of mother-to-child transmission programmes. Bulletin of World Health Organization. 82(4): 2004; 299–307.

- Centre for Social Science Research. Long Life. Positive HIV Stories. 2002; Pinifex Press: Cape Town.

- G Dowsett, P Aggleton, S-C Abega. Changing gender relations among young people: the global challenge for HIV/AIDS prevention. Critical Public Health. 8(4): 1998; 291–309.

- A Harrison, N Xaba, R Kunene. Understanding safe sex: gender narratives of HIV and pregnancy prevention by rural South African school-going youth. Reproductive Health Matters. 9(17): 2001; 63–71.

- Department of Health, Republic of South Africa. Tracking Progress on the HIV/AIDS and STI Strategic Plan for South Africa June 2000–March 2003. At: 〈http://www.doh.gov.za/aids. 〉. Accessed 1 July 2004.

- S Moore, D Zimazi. Reproductive health problems. M Goosen, B Klugman. South African Women's Health Book. 1996; Oxford University Press: Cape Town, 446.

- Women's Health Project. Infertility: A Literature Review and Annotated Bibliography. 1997; University of the Witwatersrand: Johannesburg.

- SJ Dyer, N Abrahams, M Hoffman. Infertility in South Africa: women's reproductive health knowledge and treatment-seeking behaviour for involuntary childlessness. Human Reproduction. 17(6): 2002; 1657–1662.

- P Orner. Breaking the silence: Black and white working class women's experiences of menopause. Psychological Bulletin University of the Western Cape. 8(1): 1998; 12–21.

- P Orner, J Harries, D Cooper. Paving the Path: Challenges to Microbicide Introduction. Report of a Qualitative Research Study. 2004; University of Cape Town: Cape Town.

- Planned Parenthood Association of South Africa. Annual Report, Johannesburg, 2003.

- Women's Health Project. At: 〈http://www.wits.ac.za/whp/rights_campaign.htm. 〉. Accessed 2 July 2004.

- J May, I Woolard, S Klasen. The nature and measurement of poverty and inequality. J May. Poverty and Inequality in South Africa. Meeting the Challenge. 2000; David Philip Publishers: Cape Town, 28–35.

- Census 2001 Key Findings (unemployment data). Statistics South Africa, Pretoria, 2001.

- Measuring poverty in South Africa. Statistics South Africa, Pretoria, 2000.