Abstract

Ten years after the International Conference on Population and Development finds the reproductive health community under threat from at least three sources: global initiatives, reforms of the health sector, and new financial modalities from donors and lenders. These challenges, however, mainly reflect the complete system failure in many low-income countries in providing basic reproductive health services to women, especially those who are poor and socially vulnerable. The reproductive health community can do a lot more to address the system failures and potential threats and take advantage of opportunities offered. The starting point should be an internal look at how the reproductive health community has performed in helping low-income countries. Understanding these changes and opportunities in the health sector is another important step, but understanding will only be effective if representatives of the reproductive health community in low-income countries are armed with the skills and tools needed to engage in health sector reforms, to take advantage of global initiatives and to effectively influence the implementation of new holistic forms of aid.

Résumé

Dix ans après la Conférence internationale sur la population et le développement, la communauté de la santé génésique est menacée sur au moins trois fronts: les initiatives mondiales, les réformes du secteur de la santé et les nouvelles modalités financières des donateurs et des prêteurs. Néanmoins, ces difficultés traduisent principalement l'incapacité totale de nombreux pays à faibles revenus d'assurer des services de santé génésique de base pour les femmes, en particulier les femmes pauvres et socialement vulnérables. La communauté de la santé génésique peut faire beaucoup plus pour corriger les lacunes des systèmes, se protéger des menaces potentielles et tirer parti des occasions offertes. Elle devrait commencer par analyser les résultats obtenus par la communauté de la santé génésique dans l'aide aux pays à faibles revenus. Comprendre ces changements et ces occasions dans le secteur de la santé est une autre étape importante, qui sera efficace seulement si les représentants de la communauté de la santé génésique dans les pays à faibles revenus possèdent les compétences et les outils nécessaires pour engager des réformes du secteur de la santé, profiter des initiatives mondiales et influencer efficacement l'application de nouvelles formes globales d'assistance.

Resumen

Diez años después de la Conferencia Internacional sobre la Población y el Desarrollo, la comunidad de salud reproductiva se encuentra amenazada por lo menos por tres elementos: las iniciativas mundiales, las reformas del sector salud y las nuevas modalidades financieras de los donantes y prestadores. No obstante, estos retos reflejan principalmente la ineficacia total del sistema en muchos paı́ses de bajos ingresos en prestar servicios básicos de salud reproductiva a las mujeres, en particular aquéllas que son pobres y socialmente vulnerables. La comunidad de salud reproductiva puede hacer mucho más para remediar las deficiencias del sistema y las posibles amenazas y beneficiarse de las oportunidades ofrecidas. El punto de partida debe ser practicar una evaluación interna de los esfuerzos de la comunidad de salud reproductiva para ayudar a los paı́ses de bajos ingresos. Entender estos retos y oportunidades presentes en el sector salud es otro paso importante, pero será provechoso sólo si los representantes de la comunidad de salud reproductiva en los paı́ses de bajos ingresos se proveen de las habilidades y herramientas necesarias para llevar a cabo reformas en el sector salud, con el fin de aprovechar las iniciativas mundiales y de influir de manera eficaz en la implementación de nuevas formas holı́sticas de ayuda.

One key feature of the 1994 International Conference on Population and Development (ICPD) Programme of Action is a move towards a holistic approach to reproductive health, away from the verticality of population programmes. The vision was of a health system and a social structure that make choices available and address difficult cultural aspects that produce female genital mutilation and other forms of violence against women. The agenda was broad, by design, covering a wide variety of services to be delivered by systems that work across sectors and social domains.

A broad and ambitious agenda under attack

Critical to the success of this ambitious agenda is the existence of national and global political will and leadership that would address long protected taboos and provide the resources needed to strengthen systems in order to deliver an expanded set of services. The first step was then to get governments to sign on to the objectives. Once that happened, the hard work of implementation would start. Some early successes in places like Bangladesh and MozambiqueCitation1 Citation2 gave the reproductive health community hope, but the ambitiousness of the agenda required a long-term commitment and vigilance. In Bangladesh, the government and a large consortium of donors agreed on an ambitious programme that: (i) prioritised reproductive health, (ii) designed patient-centered services, (iii) committed large shares of public resources to essential services, (iv) unified health and family planning wings of service delivery, (v) widened participation by civil society and women's groups, (vi) mainstreamed gender issues, (vii) addressed men and women in family planning programmes and recognised side effects of contraceptives, and (viii) treated violence against women as a public health issue. A change in government, however, brought about reversals in a number of critical policy areas such as unification of service delivery between health and family planning wings of the Ministry of Health.Citation2

Ten years into this agenda is an opportune time for the reproductive health community to regain the momentum that may have been lost since Cairo. Many factors appear to have contributed to this loss of momentum. For one thing, the act of signing on to the agenda has not automatically produced the effort and resources needed to implement it. In fact, not only were the resources not made available in many countries, but the last ten years have seen a frontal attack on the key feature of the agenda, the holistic system approach. This attack has taken the shape of global initiatives in the health sector that have reintroduced the vertical, targeted approach of addressing specific diseases and needs with little regard to the effect on the long-term impact on health systems. While the Cairo agenda did recognise that vertical programmes can feed into holistic thinking, it can be argued that the sheer volume of global initiatives in health have had a draining effect on policy and management attention to integrative thinking and planning for reproductive health programmes.

The ten years since Cairo also saw increased activity and innovations in a number of areas loosely grouped under the health sector reform heading. Some of these reforms, especially those related to financing of health services, were mainly due to the recognition that the health sector is under-financed because of low levels of tax-based public financing and the low budgetary priority typically given to health. Other reforms, however, such as decentralisation, were typically initiated by political forces beyond the health sector but could have a strong impact on the way the health sector and reproductive health programmes perform.

Complicating things further are the new ways the donor community is managing and disbursing external support to low-income countries. New language was coined and some old language was reintroduced to describe creative ways for donors to provide support that is meant to strengthen systems and get around difficulties in project financing. Coming into the international health scene were instruments such as the sector-wide approach (SWAp)–an attempt to integrate vertical programmes and coordinate external donors; basket funding–a funding mechanism that attempts to harmonise donor support; budget support–which moves away from project financing and provides funding directly into government budgets; poverty reduction strategy credits (PRSCs) and programmatic lending/credits–which take on multiple sectors' attempts to address structural issues that are barriers to poverty reduction. Then there are wonderful terms such as MTEFs (medium term expenditure frameworks), and PERCs and PERLs (public expenditure based credits and loans). Some of these new funding tools have aggregated programmes within the health sector, while others were designed for an even higher level of reforms and actions beyond the health sector, taking into account the whole economy of smaller countries.

With the re-emergence of vertical global health programmes, a new series of health sector reform initiatives, and new modes of external financial support, some in the reproductive health community are concerned about the impact on the Cairo agenda. Are all these changes attacks on the agenda or are they opportunities for the reproductive health community? This paper argues that the reproductive health community needs to better understand these changes and patterns in order to assess their impact on ICPD implementation. But understanding these trends is not enough. The reproductive health community needs to develop the capacity and skills to take advantage of these changes and to mitigate the potentially negative impacts that they may already have produced. This paper briefly introduces and explains these “threats” and “opportunities” and suggests a series of actions for the reproductive health community to consider.

Overwhelming needs and weak systems

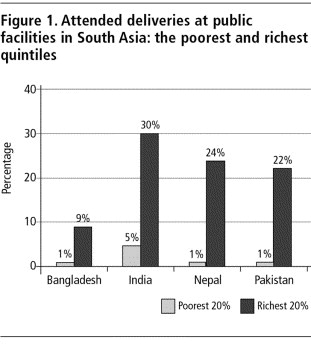

Before plunging into the quick sands of reforms and initiatives, it may be useful to focus attention on the state of affairs in some elements of the reproductive health agenda relating to access and use of services. While there are data for a number of conditions related to reproductive health, I will only focus on the use of health services relating to pregnancy, where the need for antenatal care and safe delivery are universal. The data come from Demographic and Health Surveys (DHS) conducted by the US Agency for International Development (USAID). In 1999, Gwatkin and othersCitation3 at the World Bank re-analysed 44 DHS surveys and calculated an asset index that allows us to identify the relative wealth of households in terms of quintiles. It was expected that for many countries the poor would be in worse shape in terms of health outcomes and health system outputs, but the depth and persistence of inequalities was much deeper than anticipated.Inequalities were persistent in all measures of outcomes, infant and child mortality, maternal mortality, malnutrition and fertility. Inequalities were also persistent in health system outputs across use of all forms of services, even those provided by the public sector without cost recovery. What was most striking in terms of health system outputs was the extent to which services related to many reproductive health services were more inequitable than any other cluster of services.Citation4 Footnote* In other words, poor women all over the developing world were being failed consistently by the same public sectors for health that were designed to protect them. The numbers are depressingly consistent on this public system failure. shows the level of inequalities in attended deliveries in four South Asian countries in the early to mid-1990s. A number of striking conclusions jump out of the figure. The two most graphic are the almost complete failure of the public sector in providing facility-based deliveries and how this failure is at its greatest for the poorest women (less than 6% of the poorest women deliver at a public facility in all four countries). The figures for antenatal care and any medically attended delivery (regardless of location) show equally large public sector failures. It should be noted that system failure refers not only to physically making services available, but includes education and behaviour change communication programmes that make sure that demand for these services is addressed.

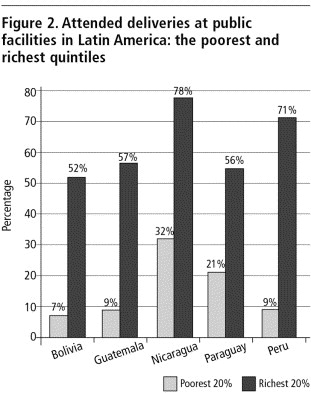

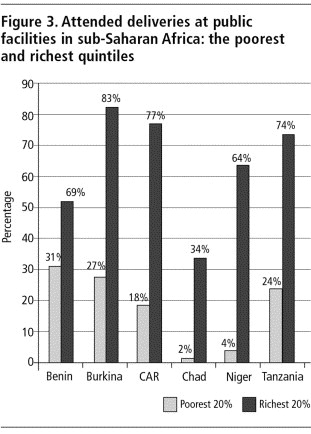

Is this type of failure unique to South Asia? Unfortunately not. highlights public sector failure in five Central and South American countries. Unlike the picture in South Asia, the public health system in Latin America seems to be doing a little better for the well-to-do in society, by housing more than 50% of attended deliveries for women in the richest quintile of wealth, but the gap between the rich and the poor is even bigger than in South Asia. shows a similar picture for six countries in sub-Saharan Africa.

Absolute system failure may be a fair way of describing how badly public systems for health care have performed in the area of reproductive health, especially for poor and vulnerable people. It is this system failure in so many low-income countries that has motivated the international health community to “do something” to address the needs, if not the rights, of women around the world. One reason for the number of global health initiatives is frustration with health systems and their inability to deliver services to the most vulnerable. Others have reacted to system failure by exploring new ways of reforming or strengthening health sectors to make them more responsive to needs and attempting to strengthen systems and capacities. Yet another response to system failures is an attempt to change financial support modalities, arguing that project and fragmented support may have actually contributed to system failures and corrupted domestic budgeting mechanisms to please donors.

But the “do something” push, whether system reforms or vertical global initiatives, has been interpreted by many in the reproductive health community as a challenge to the implementation of the Cairo agenda. A recent international conference on the link between reproductive health and health system development in Leeds,Citation5 Footnote* exposed tensions and a sizable gap in language and orientation between those advocating reproductive health and those focused on system reforms and strengthening. The main question that needs to be answered by those of us concerned about reproductive health objectives is whether system reforms and global initiatives are challenges to be fought or opportunities to be exploited.

Silver bullets: the health reform agenda

The R-word, reform, conjures dramatically different images in the minds of donors and policymakers. The word means too many different things to too many different people. When participants in the World Bank Institute's courses on Reproductive Health and Health Sector ReformFootnote† are asked what they think reform is, they have a hard time defining it. Some focus on cost recovery in health, while others mention payment mechanisms or decentralisation. What is even more interesting and revealing, beyond the lack of consensus or clarity around the term, is how the majority of the participants in these courses think that reform is bad for the reproductive health agenda. Yet the facts on the ground indicate that the only way the ICPD agenda, at least the part of the agenda that deals with the provision of services and choices, can be achieved is if health systems are dramatically improved. Health sector reforms, defined generically, can be tools for strengthening health systems.Citation6

Health sector reform has been written about, researched, evaluated, vilified, praised, defined, redefined, and reviewed to death over the last 20 years.Footnote* As a public service to the reader, I will not try to summarise that effort. Regardless of where we stand on specific reforms or the health sector reform agenda, a critical issue for the reproductive health community is that failure to understand these reforms or to engage in them would likely make reproductive health objectives the victims of reform.

Take for example popular reforms such as decentralisation, which focus on the overall organisation and management of health service delivery in the public sector. Decentralisation is typically driven by political dimensions outside the health sector but can have a profound impact, positive or negative, on health systems and outcomes. A decentralisation process that empowers informed local decision-making and is open to women and the poor to fully participate in the accountability mechanism of service delivery will most likely impact positively on reproductive health concerns. On the other hand, a decentralisation process can lead to the capture of decision-making and accountability mechanisms by local elites who are hostile to reproductive health concerns and would most likely impact the reproductive health agenda negatively.Citation8

The technical dimensions of reforms are equally important. If decentralisation of health services were designed in a way that did not take into account functions that cut across more than one level of care, such as surveillance or referral, reproductive health outcomes could conceivably deteriorate, even if accountability issues are well addressed. It is critical, therefore, to identify and map functions and actors in a decentralised process and to make sure that the roles of the different levels of a health system cover all the critical functions and reinforce each other. Failure to address these needs at the design stage, or to introduce monitoring mechanisms to make sure that critical functions are implemented, is likely to produce negative health outcomes, including for reproductive health.

The main message for the reproductive health community should be that the enemy is not reform of health systems that are failing poor people, especially poor women, but that the way reforms are designed and the process of implementation is key. In fact, the failures of the health system that were identified in the previous section should be what drives the reform agenda in the health sector. Through knowledge of technical dimensions of reform and the importance of the process of implementing reform, the reproductive health community can be the driver of reform instead of the victim.

Too much of a good thing! Serial global health initiatives

A clear threat to any broad approach to improving health systems is a return to verticalisation and competing disease-driven agendas. The ICPD agenda is clearly under threat from the amazing growth in global health initiatives, which individually are extremely well meaning but as a totality threaten any attempt at rational support to the neediest countries in the world, especially where health systems are weak. The list below was the result of a 15-minute search on 〈Google.com〉 with the following three words: global health initiative (the list is in no particular order):

Women's Health Initiative

WHO–UNAIDS HIV Vaccine Initiative

WHO's 3 by 5 Initiative

Global Alliance for Vaccines and Immunizations

Global Polio Eradication Initiative

UN Global Media AIDS Initiative

Tobacco Control Global Initiative

Global Health Information Network

Roll Back Malaria

Reproductive Health Initiative International Project

Red Cross and Red Crescent ARCHCI Africa Health Initiative

New Global Initiative to Combat Interpersonal Violence

The Nation's Voice on Mental Illness Global Partnership Initiative

Measles Initiative

Malaria Vaccine Initiative

Global Initiative for Asthma Learning Program

International AIDS Vaccine Initiative

IMB's Global Health Care Initiative

Global Health Trust

The Hope Initiative

Stop TB

The Global TB Research Initiative

Global School Health Initiative

Global Initiative to Strengthen Maternal and Reproductive Health Services

Global Initiative to Fight Hunger

Global Initiative for the Elimination of Avoidable Blindness

Global Health Equity Initiative

Global Health Action

Global Initiative to Educate Women About Contraception

Diabetes Action Now

Canadian International Immunization Initiative

Integrated Management of Childhood Illnesses

The Breast Health Global Initiative for Countries with Limited Resources

Global Initiative to Promote the Consumption of Fruits and Vegetables

Taken individually many of these initiatives make a lot of sense and are hard to argue against. Reading the materials posted on their websites, the sense of urgency and the frustration with system failures in health are obvious and widely shared. They highlight the basic dilemma of either acting quickly to address a pressing health need or thinking holistically and systematically about reforming and improving the health sector. The answer probably lies someplace in between, where some health outcomes may need quick action but most require systemic change. That balancing point probably differs from country to country and depends on both the nature of the health needs and the extent of system capacity and failure.

But regardless of what the right balance is between action now and long-term system investment, the current environment of serial global initiatives may be complicating the picture for many low-income and low-capacity countries. This is especially true when governments have to spend limited human resources on filling out applications, maintaining parallel information systems, producing specific reports and demonstrating ownership of globally designed vertical initiatives in order to get funding. Addressing the informational needs of these initiatives is demanding in terms of time and attention in client countries and typically takes the most qualified staff away from managing health systems to serve as staff to these initiatives. Moreover, these circumstances pose a direct threat to reproductive health issues and programmes at the country level because they favor activities that are easy to define and relatively easy to implement in narrow and vertical ways, and by doing so turn back the clock on the broad approach advocated in Cairo.

At the global level, serial global initiatives, especially large initiatives focused on communicable diseases, pose a different threat to the reproductive health agenda. This threat is manifested in the competition for attention and resources from donor countries and technical and financial agencies. Since human and financial resources for development assistance are limited, it is reasonable to expect that the new and large initiatives will receive the lion's share. This leaves the reproductive health community in a more difficult position to fight for attention and resources to re-invigorate the support for the Cairo agenda. This will also force the reproductive health community to find ways to simplify and make operational the programme of work, as well as to become much more adept at quantifying the outcomes expected, the outputs needed to achieve those outcomes, and the resources and inputs needed to produce the outputs. The ability to make the argument for resources and to measure results and effectiveness is critical in this environment for development aid and as I discuss below, the reproductive health community has a long way to go to be an effective player in this environment.

Before going on to the next threat, it is important to note that these new initiatives do sometimes offer opportunities for those interested in furthering the reproductive health agenda. We should not simply dismiss all these initiatives as too vertical and not take advantage of opportunities to help countries to get badly needed resources for programmes that fall within reproductive health. A good example is to see how resources for HIV/AIDS can be used to strengthen reproductive health services in Africa and Asia.

Modalities matter

At the same time as global initiatives in health are proliferating at an unsustainable pace, there are consistent global efforts to move in the exact opposite direction by convincing donors and lenders to move away from verticality and projectisation into sector-wide approaches and budget support programmes. In some ways, this push away from projects is another reaction to the wide system failure discussed above.

The arguments for changing how donors and lenders support governments reflect a frustration with the approach that was focused on simple and measurable outcomes in the short run and that lost the focus on the critical functions of local institutions and on the importance of addressing systemic weaknesses instead of simply bypassing them. While this discussion is by no means new, it has received a strong push in the recently published World Development Report 2004: Making Services Work for Poor People,Citation8 and is dominating the debate at international financial institutions and many bilateral donors.

The argument is that a fragmented approach to aid flows has a strong negative impact on service delivery and priority-setting mechanisms in recipient countries. This approach also results in high transaction costs due to the large number of parallel structures developed and maintained to address the needs of the donor/lender. Another negative impact of the vertical or project approach is that donors/lenders select the inputs they want to provide (either due to preference of what the donors deem important or due to tied aid to goods and services from the donor country) leaving the domestic budget to cover other expenditures and by doing so creating a two-sided dependency.

Instead of a project-based or vertical approach to supporting the health sector, it is argued that a donor-coordinated, sector-wide approach that is aligned to the recipients' budgeting and institutional set-up is much more effective in the long run, by helping countries develop local systems that remain after aid ends. An even more holistic aid approach would be a budget-support modality that goes beyond one sector and allows countries to receive aid directly into their budget in an untied fashion but against agreed expenditure plans and expected outcomes.

Here again, this relatively new way of doing business offers opportunities as well as risks for the reproductive health community. At issue is the extent to which reproductive health activities receive more or less attention and resources in a project versus a programme approach to financial aid. More specifically, an empirical question is the extent to which the health sector gets more or less money from national budgets and within that the extent to which reproductive health programmes receive more or less money. The answer, again, is that it depends on the ability of the reproductive health community to support client countries, especially those looking after reproductive health function in these countries.

In order for reproductive health concerns to be addressed in a SWAp or programmatic approach, a clear and convincing case needs to be made to decision-makers within the ministries of health and finance in client countries as well as to donors and lenders supporting these programmes. Such a case needs to be made technically and empirically with a clear recognition that there will not be enough resources to do everything, so strategic thinking is needed to phase in support.

Taking a hard look in the mirror

This assessment of the threats we face in the reproductive health community would not be complete or honest if it did not take on our own failures. It can be argued that the environment of change described to some extent in this paper has exposed the limitations and weaknesses in the attempt to make implementation of the Cairo agenda a reality around the world. There are at least three areas where we can be much more effective in helping our country counterparts: definition, advocacy approach and empiricism.

The boundaries of reproductive health

Participants in the World Bank Institute's courses on Reproductive Health and Health Sector Reform are given an exercise of attempting to define the boundaries of reproductive health and more often than not reach the conclusion that it is very difficult to say where reproductive health starts or stops. While that conclusion is consistent with the all-encompassing approach that partly defined ICPD, the inability to clearly and convincingly define any programme has a strong and negative impact on the ability to advocate for it when competing for public and donor resources.

This poses a difficult dilemma for people advocating for reproductive health within budgets: in order to get resources and gain ownership we have to simplify and streamline programmes in ways that are counter to the inclusiveness agenda. It can be argued, however, that this is not an all-or-nothing situation, and that the solution should be in local communities and national programmes taking a phased approach that is consistent with their financial and capacity constraints. In other words, it is conceivable to fashion a long-term vision of reproductive health that pushes limited boundaries, and to define short- and medium-term programmes that are manageable and easier to sell to those that make decisions about budgets. Decisions on what gets priority in the short and medium term have to take into account the needs of the country, especially of those who are poor and socially vulnerable.

Rights, rights, rights

A repeated refrain heard at the recently held conference on reproductive health and health systems mentioned earlierCitation5 is that one of the reasons for the failure of public systems to provide services to women is that a “rights-based” approach has not been followed. It is easy to see why the concept of a rights-based approach is appealing to a large number of reproductive health advocates and activists. A more difficult question is to what extent this argument is resonating with decision-makers in low-income and low-capacity countries where the totality of public spending on health is in single-digit US dollars per person per year. Faced with extremely binding financial and capacity constraints, the concept of rights may actually scare people away from opening doors they cannot control.

A more practical approach that might help the reproductive health community to secure more resources in low-income settings may be to focus on expected outcomes and the extent to which investment in reproductive health services would save lives, reduce suffering and help address socially and culturally challenging problems. We can learn from the experience of the nutrition community in the early 1990s when they developed empirical bases for assessing the returns to investment in nutrition and produced a computer programme that can help countries quantify outcomes in terms of mortality, morbidity, loss of cognitive abilities in children and loss of productivity in adults.Footnote* It is hard to argue against saying that all children should have the right to grow up free of hunger or nutritional deficiencies, but the argument that resonated in many poor countries was the focus on outcomes, not rights.

Give me the numbers

Not only do we not have a good handle on how to measure outcomes (unlike the nutrition or child health communities), but there is confusion in the international health community about how we measure health system outputs to achieve these outcomes and how we cost interventions that produce these system outputs. In many ways, the reproductive health community has a wonderful story to tell, but lacks the empirical foundations to tell the story to those who can do something about it. Maternal mortality and morbidity are among the reproductive health outcomes that are most often used but they are not easy to measure either consistently or over time in many countries. Measuring health system outcomes in reproductive health is not trivial either. Take, for example, attended deliveries, where even standardised surveys such as the Demographic and Health Surveys can be interpreted differently in different contexts, especially between Africa and Asia, with the issue being who is attending the delivery, their training, skills and qualifications, which differ from region to region and country to country. More intractable than the difficulty of measuring some health system outputs, is the dearth of empirical evidence in the scientific literature on the types of health system outputs that can produce the desired reproductive health outcomes. With difficulties in measuring outcomes and system outputs needed to achieve them, and the lack of scientific clarity on how to achieve the desired outcomes, it is not hard to see why the policy and budget dialogue often does not favour reproductive health services.

A way forward

Ten years after Cairo may provide an opportunity to review how far the reproductive health community has gone in achieving its ambitious and important agenda, and also an opportunity to develop practical steps to increase the likelihood that the year 2014 finds more results on the ground. A number of actions have already been discussed above, so instead of a summary it may be helpful to close with a brief discussion of two key principles that can pull all these actions and steps together into an action framework: building on-the-ground capacities and a new empiricism.

A starting point for thinking about moving the reproductive health agenda forward is the recognition that achieving tangible results will require sustained engagement by national representatives of the reproductive health community in each and every country that needs assistance. In other words, it is critical to find ways to arm reproductive health programme implementers and activists with the skills and tools needed to engage in health sector reforms, to take advantage of global initiatives, and to effectively influence the new holistic forms of aid support. Policymakers, managers, private sector contributors, civil society advocates and academicians in these countries are the ones that face the challenges and opportunities and are the only ones that can do something about it at the national and sub-national levels. The reproductive health community should then target their support to building capacity for and make tools available in areas such as economics, finance, political mapping, epidemiology, behaviour change, analytical tools, listening tools and advocacy skills. If we take for example a health sector reform agenda in a country, the reproductive health community in that country should have the skills and tools to help with:

the problem definition by ensuring reproductive health outcomes are documented and highlighted, preferably empirically,

the diagnosis of the causes of these problems and the bottlenecks for implementation,

the policy development, including the development of the expenditure programmes to implement new policies,

the political decision-making process that either ensures a reform works or fails to take off,

the actual implementation of the reform agenda to ensure that words do become actions, and

the monitoring and evaluation to ensure lessons are learned and used to improve design.

Building capacity for such skills is not an easy or cheap exercise, but without them, the reproductive health community is likely to continue to stay on the outside trying to get in.

While most of the battles and engagement typically take place at national and sub-national level, a lot can be done at the global level that would strengthen the hand of people on the front lines. For the reproductive health community to be effective in re-capturing the attention of policymakers and financiers, investments in quantification are needed. As noted in the body of this paper, the reproductive health community has difficulties in measuring reproductive health outcomes, health system outputs that are likely to achieve these outcomes, and the cost or budgetary implications of designing, implementing or expanding these health system outcomes. Without a better command of the empirical arguments and language, it will be difficult to consistently convince decision-makers that the reproductive health community is not only focused on describing the problem, but has taken measurable steps to finding practical programmes that can be implemented within reasonable budget constraints. Investments in building the empirical knowledge, evidence and arguments for reproductive health are needed for the long-term success of the reproductive health agenda.

Notes

* A possible exception would be family planning services, especially those delivered through outreach mechanisms.

* Making the Link between Sexual and Reproductive Health and Heath System Development. 9–11 September 2003, Leeds, UK.

† The World Bank Institute developed a programme on Reproductive Health and Health Sector Reform in 1998 and has been offering versions of this course globally and regionally since then. Participants in these courses include government officials from Ministries of Health and Planning, civil society representatives, academicians and staff from bilateral and multilateral agencies. See 〈http://www.worldbank.org/wbi/healthandpopulation〉.

* An excellent treatment of health sector reform exists in Getting Health Reforms Right.Citation7

* The PROFILES computer programme is based on existing scientific knowledge on the returns to nutrition interventions and has been used in a number of countries to help make the economic and health argument for public investments.

References

- A Germain. Making the link: sexual and reproductive health and health systems. Keynote speech at Making the Link: Sexual-Reproductive Health and Health Systems, Leeds. 9–11 September 2003

- R Jahan. Sustaining advocacy for the ICPD agenda in health reforms under regime change: lessons from Bangladesh. Presentation at Making the Link: Sexual-Reproductive Health and Health Systems, Leeds. 9–11 September 2003

- DR Gwatkin, S Rutstein, K Johnson. Socioeconomic Differences in Health, Nutrition, and Population. 2000; World Bank, Health, Nutrition, and Population Department: Washington DC.

- DR Gwatkin, S Rutstein, K Johnson. Overcoming the inverse care law. September 2002; Leverhulme Lecture, London School of Tropical Medicine.

- Making the Link: Proceedings of Conference on Making the Link: Sexual-Reproductive Health and Health Systems, Leeds, 9–11 September 2003, University of Leeds/London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine. 2004

- K Krasovec, RP Shaw. Reproductive health and health sector reform: linking outcomes to action. Draft paper for Module 7, Core Course, Adapting to Change: Population, Reproductive Health and Health Sector Reform, World Bank Institute, Washington DC. 2000

- MJ Roberts, W Hsiao, P Berman. Getting Health Reform Right: A Guide to Improving Performance and Equity. 2004; Oxford University Press: Oxford.

- World Bank. World Development Report 2004: Making Services Work for Poor People. 2003; Washington DC, World Bank and Oxford University Press.