Abstract

High sex ratio at birth due to son preference has been known in China historically, but it was thought this phenomenon would diminish with modernisation. The aim of this study was to investigate abortion decisions and reported sex ratios at birth in the context of successive family planning policies in Huaning County, Yunnan Province, in China. Abortion patterns and reported sex ratios at birth of a random sample of 1,336 women aged 15–64 were analysed for the period 1980–2000, in relation to parity and sex of previous children. There was a male bias in the abortion pattern during the 1980s, but by the end of the 1990s most pregnancies of women with two children were being terminated. Sex ratio at birth rose from 107 in 1984–87 to 110 between 1988–2000 in Huaning. While women's reproductive decisions were influenced by son preference over the whole period, the means used to ensure a son differed with changing family planning policies. We conclude that rising sex ratios in the context of falling fertility and modernisation is an alarming socio–demographic issue, which defies historical experience. Assumptions that discrimination against girls would diminish with economic development and female education have proven simplistic. Action is urgently needed to reduce and mitigate the effects of discrimination against girls.

Résumé

La Chine enregistre depuis longtemps un rapport de masculinité élevé en raison de la préférence pour les fils, mais on pensait que ce phé nomè ne diminuerait avec la modernisation. Cette é tude a analysé les dé cisions d'avorter et les rapports déclarés de masculinité à la naissance, dans le contexte des politiques successives de planification familiale dans le comté de Huaning, province du Yunnan, en Chine. Elle a é tudié les avortements et les rapports de masculinité à la naissance sur un é chantillon de 1336 femmes de 15-64 ans sur la pé riode 1980-2000, par rapport à la parité et au sexe des enfants pré cé dents. Pendant les anné es 80, les décisions d'avorter révélaient une partialité en faveur des garçons, mais à la fin des années 90, la plupart des mè res de deux enfants interrompaient leur grossesse. À Huang, le rapport de masculinité à la naissance est passé de 107 entre 1984–87 à 110 entre 1988–2000. Pendant toute la période étudiée, les décisions des femmes étaient influencées par la préférence pour les fils, mais les moyens employés pour s'assurer un garçon variaient avec l'évolution des politiques de planification familiale. La hausse des rapports de masculinité, face à la baisse de la fécondité et la modernisation, est un phénomène socio-démographique inquiétant, qui dé fie l'expérience historique. Il était simpliste de penser que la discrimination à l'égard des filles diminuerait avec le développement économique et l'éducation des filles et il faut agir d'urgence pour réduire les effets de cette discrimination.

Resumen

En China se ha sabido por años que hay preferencia por hijos varones pero se pensó que este fenó meno disminuira con la modernizació n. Este estudio investigó el aborto y las proporciones de sexos entre los recién nacidos en las politicas de planificació n familiar en Huaning, Yunnan, en China. Se analizaron las decisiones para abortar y las proporciones de sexos entre recié n nacidos en una muestra aleatoria de 1,336 mujeres de 15 a 64 años entre 1980 y 2000, en relación con la paridad y el sexo de los hijos anteriores. Durante los años 80, se experimentó un sesgo hacia el sexo masculino en los abortos, pero a fines de los años 90, las mujeres con dos hijos decidian abortar. En Huang, la proporción de varones recié n nacidos aumentó de 107 por cada 100 niñas entre 1984–87 a 110 niños por cada 100 niñas entre 1988–2000. A pesar de que durante todo este período las decisiones de las mujeres fueron influenciadas por su preferencia por tener un varó n, los medios utilizados para garantizar su nacimiento cambiaron con las polí t́icas de planificación familiar. El aumento en la proporción de varones entre recién nacidos en una fecundidad declinante y la modernización es un aspecto sociodemográ fico alarmante que desafíà la experiencia histórica. Fue simple pensar que la discriminación contra las niñas disminuiríà con el desarrollo econó mico y la formación de las mujeres. Es apremiante la necesidad de tomar medidas para disminuir y atenuar los efectos de la discriminació n contra las niñas.

Reproductive decisions occur in specific political, socio-economic and cultural contexts that may oblige women to “choose” one alternative over another.Citation1Citation2 For example, in patriarchal societies with strong son preference, combined with official policies to limit family size, a woman may opt for abortion or contraceptive use if she has a son already, but continue childbearing if she has “only” daughters. This is apparent in the male bias in abortion and contraceptive use patterns found in many countries.Citation3Citation4Citation5Citation6Citation7 Highly distorted sex ratios at birth are a more sinister sign of son preference, which plague some South and South East Asian countries.Citation8Citation9 China has the most severe shortage of girls compared to boys of any country in the world.Citation10 In the early 1970s, cohort sex ratios were normal in China.Footnote* The trend was reversed in the mid-1970s and increasing sex ratios occurred into the 1990s.Citation11 Son preference has been considered particularly strong in rural areas and among less educated parents. Therefore, the overall trend in sex ratios at birth had been expected to decrease along with economic development and improvements in education, particularly women's.Citation12 Contrary to these expectations, several authors have demonstrated how sex ratios at birth and excess female child mortality have continue to increase despite a rapidly developing society.Citation8Citation9Citation13Citation14

In order to achieve desired family size and sex composition of children, different reproductive strategies may be used: contraception, induced abortion, infanticide, abandonment or adoption in or out. Excess female mortality in utero, presumably the result of sex-selective abortion, excess female mortality in infancy or childhood, out-migration of female children, presumably to international adoption, and sex-selective undercounting of children in censuses and surveys all occur in China.Citation10Citation11Citation14 Cai and Lavely analysed reported births from 1980 to 2000 and estimated the number of missing girls to be 12 million China-wide, of whom they calculated a third were unregistered, as opposed to dead.Citation11 Recent research shows that the combination of son preference, low fertility and use of reproductive technology such as ultrasound for sex determination is causing the shortage of girls in China and other parts of Asia, e.g. South Korea and Taiwan. In China the government's guided family planning programme has further exacerbated the dearth of girls.Citation10Citation14

The aim of this study was to investigate the influence of son preference on women's reproductive decisions, as reflected in abortion patterns and reported sex ratios at birth in the context of successive family planning policies. We analyse women's abortion patterns in relation to parity and sex of previous children, and the sex ratio at birth over the last decades among a rural population in the province of Yunnan, southern China. We demonstrate how strongly compulsory family planning policies have penetrated one of China's most remote and least developed counties. Further, we suggest that although women's reproductive decisions have been influenced by son preference all along, their routes to reach their fertility goals have been adapted in response to changing political, demographic and technological conditions.

Background

In the beginning of the 1970s, when the Chinese government initiated the wan xi shao (late marriage, longer intervals and fewer births) campaign, the average number of children born to Chinese women was close to six. In 1978 it had declined to less than three children per woman.Citation15 The end of the 1970s was also a period of a series of social and economic reforms, which brought about rapid economic growth. Starting in rural areas in 1978, rural co-operatives were dismantled and the family-based economy gradually re-instituted, including approval of local markets and a wide variety of rural enterprises.Citation16

Paralleling the economic reforms, the one-child policy was introduced in an effort to curb population growth. In its first phase, 1979–83, implementation became increasingly strict with mandatory IUD insertions for women with one child, sterilisation for couples with two or more children, and abortions for unauthorised pregnancies. The total number of reported abortions reached 14 million in 1983, during the first phase of the one-child policy. A phase of policy moderation began in 1984, extending the range of conditions under which a second child could be permitted; for example, rural “daughter-only” households were permitted a second child. During this period the total number of reported abortions dropped to nine million.Citation7 As a result of a sharp increase in fertility rates in the late 1980s, there were renewed official demands for stricter implementation of the one-child rule.Citation1 All the same, the policy permitting a second child after the birth of a daughter was officially extended to all rural areas in 1988. At the beginning of the 1990s, the one-child policy was still encouraged but rigorous application was mainly in the larger cities and the most populous provinces.Citation17 By 1995, China's abortion ratio had stabilised at about 27 per 100 known pregnancies.Citation18

The major objectives of China's State Family Planning Commission for the period 1995–2000 were to cut the natural growth rate to less than 10 per 1,000 by 2000, and to keep the total population under 1.3 billion by 2000.Citation19 According to the 2000 census, the population was 1.265 billion in November 2000.Citation20 The total fertility rate has officially been estimated at 1.8, (replacement level is 2.1). However, analysis of Chinese population statistics shows serious defects, such as under-reported births and contradictory migration data.Citation21Citation22

Some studies suggest that China has had a shortage of girls and women for centuries. Sex ratios of cohorts born in the first half of the 20th century were abnormally high, but fell rapidly among those born in the first decades of the People's Republic. By the beginning of the 1970s, the cohort sex ratio in China was within the normal range, but since then it has risen steadily.Citation10Citation11 It reached 108 in the year 1984 and has not dropped below that since then.Citation18 In 1985–87, the official sex ratio at birth was between 110 and 112. Alarmed by these figures, in 1987 the Ministry of Health issued a new law strictly forbidding sex selective abortions and the use of medical technology to perform antenatal sex determination.Citation23 All the same, between 1990 and 2000 it rose from 112 to 118.Citation8Citation11Citation24 In the 2000 census figures, the ratio was 114 in the cities and 122 in the rural areas.Citation25 In 2000 and 2001, the People's Republic of China issued two major documents on reproductive policy, the 2000 Decision and the 2001 Law. Both emphasise the need to maintain China's recently achieved low birth rate, reaffirm existing family planning policy and improve implementation. The Decision the need to notes improve the sex balance and to provide a pension programme for the ageing population, thereby implicitly acknowledging that the programme itself may have exacerbated the abnormal sex ratio.Citation26

Data and methods

Our study was conducted in Huaning county, Yunnan province, southwest China, in May–June 2000. With a population of nearly 37 million, Yunnan is one of China's poorest provinces. In 2000, 87% of the population were peasants and the illiteracy rate was 50%, of which 70% were women. Huaning is a mountainous county located in the southeastern part of Yunnan. In terms of socio-economic development, it falls in the middle range of counties in the region.Citation27 The total population of Huaning in 2000 was 198,000, with over 90% engaged in agriculture. The Han ethnic group constitute about 85% and the rest belong to Yi, Miao, Hui and other ethnic minorities. Huaning county was purposively selected, based on the local authorities' willingness to cooperate.

The study population was all women aged 15 to 64 in Huaning. This age span was chosen to cover women who had reached reproductive age at the time of the foundation of the People's Republic of China, i.e. in 1949, and women reaching reproductive age at the time of interview. In rural China, each county is divided into townships and each township into administrative villages. These consist of a number of “natural villages”, which are composed of groups or clusters of houses lying close to each other. Based on lists provided by the local authorities, multi-stage cluster sampling techniques were used to randomly select three townships out of five, and ten administrative villages out of 48. In each administrative village half of all natural villages were selected and in these all households were visited. All eligible women at home at the time of the visit were asked for an interview. Due to a shortage of funds, we were unable to revisit families where the woman was not at home but continued to a neighbouring family until we achieved a total sample size of 1,503 women.Footnote* No one refused to participate, which is common in China for this kind of survey. After cleaning the data set, i.e. checking for missing variables and internal inconsistency, 1,336 cases remained, of whom 1,111 were married.

Pre-coded questionnaires asked for background data on the woman, the timing of marriage, pregnancy histories and contraceptive use.Footnote† Key dates were entered into a Life History Calendar (LHC), a tool that is often used in demographic surveys to enhance the precision of retrospective data on personal events in people's lives.Citation29Citation30 Reference was also made to the Chinese lunar calendar. Female health workers with extensive experience of previous surveys conducted the interviews in the women's homes. The first author, a Swedish social scientist fluent in Chinese, took part in all aspects of the survey except the interviews.

The 1,111 married women,Footnote** were asked whether they had ever had an induced abortion; their answers were analysed by ethnicity, religion, educational levels and occupation. For the years 1980 to 2000, the abortion ratio (number of abortions per 100 known pregnancies) was calculated by five-year periods and analysed by number and sex of the women's previous children.Footnote* The abortion ratios were also aggregated for the whole period 1980–2000 and the relative risk calculated between combinations of adjacent sexes. In calculating the reported sex ratios at birth, we used the time periods 1984–87 and 1988–2000, as they represent distinct phases in the implementation of the one-child policy. This division of years also makes the analysis comparable with data in the literature.Citation1

Findings

Abortions by socio-economic background

Among the 1,111 married women, 36% said that they had had at least one induced abortion (Table 1

). There were no significant differences in the incidence of abortion with regard to any of the background variables. Of the abortions reported by ethnic minorities, 20% were performed in the 1980s and 66% in the 1990s. The corresponding figures for the Han women were 32% and 49%. The reason abortion peaked out later for ethnic minority women is probably that in the 1980s the family planning policy was much more relaxed for them compared to the Han majority, but by the late 1990s compliance with policy was being tightened for minorities too.Abortions by calendar year for first- to third-order pregnancies

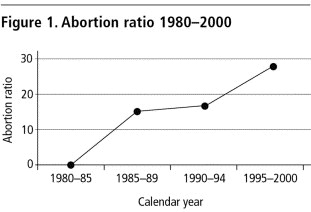

The increase in induced abortions among first- to third-order pregnancies between 1980 and 2000 is shown in FootnoteFigure 1

Prior to 1985, there were few abortions among low-parity women, less than 1% in 1980–85. The abortion ratio started to increase after 1985, reaching an average of 15–16 abortions per 100 known pregnancies between 1985 and 1994, rising to 27 per 100 known pregnancies in 1995–2000.

Abortions by sex and number of previous children

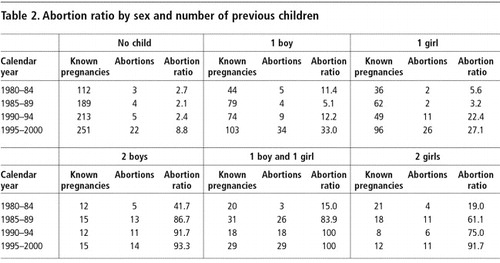

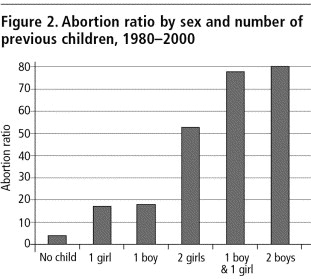

shows the number of abortions per 100 known pregnancies from 1980, by the number and sex of the woman's previous children. Because of high fertility in the 1960s and early 1970s, there were large increases in the number of women reaching childbearing age and having their first pregnancy from 1980–84 onwards. Among women with no previous children, there were very few abortions, with a slight increase during the period 1995–2000 when the abortion ratio reached 9. Among women with one child, the ratio remained relatively low up to 1990, irrespective of the sex of that child. During the 1990s the ratio increased gradually, reaching 33 for women with one son and 27 for those with one daughter. Among women with two children, the abortion ratio remained relatively low up to the mid-1980s, when it rose sharply for women with two sons. During the 1990s, it rose further for all women with two children, and by the late 1990s, almost all pregnancies of women with two children were terminated. There were no significant differences between the women according to the sex composition of their living children.shows the accumulated data for the period 1980–2000. Women with one child, whether a son or a daughter, are treated as one group. The data show that women with a son and a daughter and women with two sons had equally high abortion ratios. There was a significantly higher risk of abortion among these women than among women with two daughters, mainly reflecting the differences found in the early 1980s. (The relative risk was 2.04, chi-square test, p< 0.01).

Reported sex ratio at birth by period of years and parity

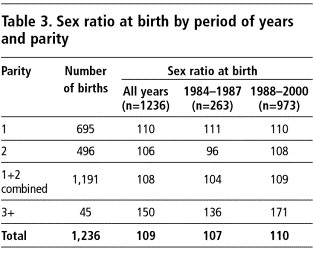

Trends in the sex ratio at birth from 1984 to 2000 are shown in Table 3

Overall, 109 births of boys were reported for every 100 births of girls. During the period of policy moderation in 1984–87, the sex ratio at birth was around 104 for parities 1 and 2 combined, and 136 for parities 3+, with an average of 107 for all birth orders combined. During the period 1988–2000 the sex ratio at birth increased across all birth orders, reaching an average of 110 boys reported per 100 girls.

Discussion

Recall bias is a well-known problem in retrospective surveys and such data should always be interpreted with some caution. Caspi et alCitation31 have pointed to the advantage of event history data over longitudinal data collected at fixed points in time. Other authors have suggested various means of enhancing the accuracy of retrospective recall, e.g. the use of landmarks, i.e. major life events.Citation32 We used the life history calendar and observed that the visual display of the calendar helped the respondent relate to the timing and sequence of events, and also helped the interviewer to correct and cross-check inconsistencies. Questions about events such as change of residence, marriages, births and deaths–all important landmarks in people's lives–seemed to help the women connect to less easily remembered events. However, the under-reporting of abortion in surveys is a special problem; both intentional and unintentional errors are known to occur even in countries where abortion is legal and widespread.Citation33Citation34 In China, as in many countries, abortion is a sensitive topic and there may have been some intentional under-reporting in our survey for reasons of privacy. With these reservations, we do not suspect systematic bias but are confident that the relative levels and trends in our data reflect actual changing patterns.

After the introduction of the one-child family policy in 1979, Chinese women were officially urged to cease childbearing after the birth of their first child, even though there have been a range of conditions under which a second child has been permitted. Analysing the abortion pattern in Huaning during successive policy periods, we have demonstrated that abortion ratios have increased for every sex composition over time and dramatically across parities. For example, the abortion ratio for women with two daughters rose from 19 per 100 reported pregnancies to 92 between 1980 and 2000. Moreover, the pattern is much more sharply differentiated with two children than with one. In the 1980s, there is no appreciable difference between women with two boys compared to those with a boy and a girl, but in 1990–2000 it is higher for those with one of each sex than for those with two boys; thus, abortion had become virtually universal for women with two children. Family planning programme requirements have obviously penetrated strongly into Huaning. We agree with Lavely (William R Lavely, personal communication, May 2004), that the apparent gender neutrality has more to do with the effectiveness of policy enforcement than with diminished desire for sons.

Sex ratios at birth display a different pattern. During the phase of policy moderation 1984–87, the sex ratio at birth in our study was 107, only slightly over the normal ratio and similar to that of Yunnan province as a whole.Citation8 During the period 1988–2000, it rose to an average of 110 for all parities combined, which is considerably above the normal ratio but below the even higher annual ratios in other counties and cities in China.Citation10 Based on socio-economic data, Skinner et al have modelled China's macro-regions according to a hierarchical structure of cities, towns and their respective rural areas. In this model, reported sex ratios at birth and in the first year of life (juvenile sex ratios) are lowest in the inner, urban core and increase as one moves out to the periphery. Huaning falls in the middle core of the Yungui macro-region, whose inner core is the area around Yunnan's provincial capital, Kunming.Citation27 Juvenile sex ratios from the 2000 census show a ratio of 101.5 for Kunming, an increasing ratio for adjacent counties, e.g. 106 for Huaning, and in the more peripheral areas to the northeast as high as 133.8 in Huize county (G William Skinner, personal communication, May 2004). As juvenile sex ratios under normal conditions are lower than sex ratios at birth, our finding of a sex ratio at birth of 110 seems to tally well with the juvenile ratio of 106 in Huaning.

Thus, while the son preference apparent in the reported sex ratios in our study is less extreme than in other parts of Yunnan and China, it is still higher than normal, and above all, it is currently increasing. It appears that Huaning women's reproductive decisions have been influenced by son preference over the whole period, but that the routes to reach their fertility goals have differed in response to differing policies, to fertility levels and to other conditions such as the availability of technology for fetal sex determination. As the fertility rate has fallen and the chances for a son thereby decreased, women's strategies have shifted to more effective means of achieving their fertility goals.

Where are the “missing girls” in Huaning? We were not able to compare our data on births with official registry data or hospital records, which might have helped to shed light on the mechanisms behind the high reported sex ratio. However, other studies have offered possible explanations. In 1991, Johansson and Nygren found that about half of the elevated sex ratios at birth could be attributed to abandonment and adoption out of infant girls.Citation35 From a household survey in three provinces in China conducted in 1995, Bogg compared the sex ratio for children below 18, reported in a household survey, with official data for the same population and period. They found a significantly lower sex ratio in the household interviews compared to the register data, indicating that girls may be under-reported in the latter.Citation23

The prevalence of sex selective abortion is for obvious reasons difficult to know. The sex ratio at birth started to increase by the mid-1970s, but ultrasound was not available anywhere in China at that time. It started to be introduced in clinics outside a few big city hospitals only in 1984. The late 1980s and 90s have seen the gradual extension of access to ultrasound throughout most of China. In rural Yunnan, however, even though some county hospitals and township health centres had acquired ultrasound equipment in the 1990s,Citation36 according to Lavely,Citation11 few people knew how to operate it. On the other hand, the fact that sex selective abortion is illegal and regarded as a serious problem by the authorities suggests that it is common.Citation11

Coale and Banister analysed annual hospital births nationwide between 1986 and 1991 and found that the sex ratio had risen from 108 to 110. Assuming no under-registration of newborn girls in the hospitals, they attributed the high and rising sex ratios to sex selective abortions.Citation24 However, induced abortion does not seem to have become a substitute for female infanticide, but rather has added to it. In fact, both seem to have increased in the 1980s and 1990s.Citation10 Cai and Lavely analysed reported births from 1980 to 2000 and estimate the number of missing girls in that period as 12 million nationwide, of which they estimate that at most one third were concealed, as opposed to dead.Citation11

On the whole, most demographic researchers on China seem to agree that there is life-threatening discrimination against girls in China.Citation9Citation10Citation11 Gu and Roy have analysed data from China, Taiwan and South Korea on rising sex ratios at birth. They suggest that this situation is likely to occur in a population in the process of development, with a cultural setting conducive to strong son preference, with rapid fertility decline, with population programmes mainly concentrating on reducing the number of children per woman, and where the technology for antenatal sex determination is easily available.Citation8 These conditions all pertain in Huaning today.

Some authors have implied that the current high sex ratios at birth that characterise China and some other Asian countries may be a transitory phenomenon that will diminish with modernisation. For example, in a 1998 article on son preference in Anhui province, Graham et al concluded that “if the big cities are trend-setters for all of China (including rural areas), then concerns about son preference may soon be part of history”.Citation37 This conclusion is not borne out by recent census data or other recent research.Citation8Citation9Citation10Citation11Citation12Citation13Citation14Citation25 For example, in the 2000 China census, urban as well as rural areas all reported higher female than male infant death rates, which under normal conditions should be the reverse.Citation25 Furthermore, census data from China, South Korea, and India between 1920 and 1990 show that female survival is threatened in periods when household resources are constrained, especially during war, famine and periods of fertility decline.Citation38

In the context of distorted sex ratios in China and other parts of Asia, concern has been raised regarding the ethics of antenatal sex selection and its implications for the status of women. One interpretation of reproductive rights might include not only the right to decide the number and spacing of children, as articulated at the Cairo conference, but also their sex. Why should a woman be denied the right to sex selective abortion if having a son will raise her status and enhance her well-being? It is a valid question with no easy answer.Footnote* One cannot know for sure today what impact future sex ratio imbalances will have on women's lives. We do know, however, that historically it has not raised their status. Today, the shortage of women has resulted in abductions, rape and kidnapping of women, which have lowered, not raised women's status.Citation10

Croll, in her recent work Endangered Daughters, suggests that rising sex ratios and the continuing need or “preference” for sons, in the context of falling fertility, results in even less space for unwanted daughters. This, she maintains, should not just be masked as “gender bias” or “son preference”, as it prolongs the “culture of silence that collectively denies and belies daughter discrimination”,Citation17 in which those girls who are born and remain unregistered will most likely have less access to education and health care, leading to higher mortality risks and fewer chances in life.Citation23

We conclude that a rising sex ratio in the context of falling fertility and modernisation is an alarming demographic and social issue, which defies historical experience. Previous assumptions, that discrimination against girls would diminish with economic development and female education, have proven too simplistic. New and refined analytical research tools are required to understand current reproductive strategies in China. Most urgently, policy-makers, women's rights activists and civil society at large must act together to reduce and mitigate the effects of discrimination against girls.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported financially by the Swedish Agency for Research Cooperation with Developing Countries (SAREC). Travel grants were from the Nordic Institute for Asian Studies.

Notes

* Sex ratio at birth is defined as the number of males per hundred females at birth. Under normal circumstances the sex ratio at birth is 105–106 boys per 100 girls.

* In households visited in the daytime, about 25% of eligible women were not at home, while those visited in the evenings were all at home.

† Certain analyses of this data set are presented in Löfstedt et al.Citation28 Other articles on contraceptive patterns, fertility and birth spacing are forthcoming.

** Only married women were asked about abortion, as this is a sensitive issue to ask unmarried women about in a survey.

* Data for the years before 1980 were collected but have been excluded from the analysis as recall would have been poorer.

* This debate is ongoing in India but with no resolution of the dilemmas in sight.Citation39

References

- S Greenhalgh, J Li. Engendering reproductive practice in peasant China: the political roots of the rising sex ratios at birth. Research Division Working Paper No.57. 1993; Population Council: New York.

- S Correa, R Petchesky. Reproductive and sexual rights: a feminist perspective. G Sen, A Germain, L Chen. Population Policies Reconsidered: Health, Empowerment, and Rights. 1994; Harvard University Press: Cambridge.

- Y Wang, S Becker, LP Chow. Induced abortion in eight provinces of China. Asia–Pacific Journal of Public Health. 5(1): 1991; 32–40.

- WI de Silva. Influence of son preference on the contraceptive use and fertility of Sri Lankan women. Journal of Biosocial Science. 25: 1993; 319–331.

- T Rajaretnam, RV Deshpande. The effects of sex preference on contraceptive use and fertility in rural South India. International Family Planning Perspectives. 20(3): 1994; 88–95.

- J Haughton, D Haughton. Son preference in Vietnam. Studies in Family Planning. 26(6): 1995; 325–337.

- P Tu, HL Smith. Determinants of induced abortion and their policy implications in four counties in North China. Studies in Family Planning. 26(5): 1995; 278–286.

- BC Gu, K Roy. Sex ratio at birth in China, with reference to other areas in East Asia. What we know. Asia–Pacific Population Journal. 10(3): 1996; 17–42.

- E Croll. Fertility decline, family size and female discrimination: a study of reproductive management in East and South Asia. Asia–Pacific Population Journal. 17(2): 2002; 11–38.

- J Banister. Shortage of girls in China today. Journal of Population Research. 21(1): 2004; 19–45.

- Y Cai, WR Lavely. China's missing girls: numerical estimates and effects on population growth. China Review. 2(3): 2003; 13–29. At: 〈http://www.chineseupress.com/promotion/China%20Review/China_review_J.html. 〉.

- S Westley. Evidence mounts for sex-selective abortions in Asia. Asia–Pacific Population Journal. 34: 1995; 1–6.

- DL Poston. Son preference and fertility in China. At: 〈http://socioweb.tamu.edu/faculty/POSTON/Postonweb/pubarticle/everything.pdf. 〉. Accessed 4 July 2001.

- SZ Li, CZ Zhu, MW Feldman. Gender differences in child survival in contemporary rural China: a county study. Journal of Biosocial Science. 36: 2004; 83–109.

- HY Tian. China's Strategic Demographic Initiative. 1991; Praeger Publishers: New York, 30–45.

- Hong Y. Effects of changing lives of women on fertility in rural China, with comparison to their husbands' roles. PhD thesis, Demography Unit, Stockholm University, 2002. p.1–19.

- E Croll. Endangered Daughters: Discrimination and Development in Asia. 1st ed, 2000; Routledge: London, 1–40.

- SK Henshaw, S Singh, T Haas. The incidence of abortion worldwide. Family Planning Perspectives. 25(Suppl.): 1999

- UNESCAP. Population and Family Planning Laws, Policies and Regulations. At: 〈http://www.unescap.org/esid/psis/population/database/poplaws/china/china14b.asp. 〉. Accessed August 2004.

- W Lavely. First impression of the 2000 census of China. At:〈http://csde.washington.edu/pubs/wps/01-13.pdf. 〉. Accessed 4 November 2001.

- UNESCAP. National Report of the People's Republic of China to the Fifth Asian and Pacific Population Conference, 2002. 2003; ESCAP: Bangkok.

- T Scharping. Hide-and-seek: China's elusive population data. China Economic Review. 12(4): 2001; 323–332.

- L Bogg. Family planning in China: out of control?. American Journal of Public Health. 88(4): 1998; 649–651.

- AJ Coale, J Banister. Five decades of missing females in China. Demography. 31(3): 1994; 459–479.

- Banister J. The dearth of girls in China today: ongoing, geography, and comparative perspectives. Submitted to UNFPA China, Sept. 2002, Final revision, Dec. 2002.

- EA Winkler. Chinese reproductive policy at the turn of the millennium: dynamic stability. Population and Development Review. 28(3): 2002; 379–418.

- GW Skinner, M Henderson, JH Yuan. China's fertility transition through regional space. Social Science History. 3(24): 2002; 614–652.

- Löfstedt P, Gebrenegus G, Luo SS et al. Gender, premarital conception and the transition from first marriage and first birth in Huaning county, Yunnan province, People's Republic of China. (Manuscript).

- D Freedman, A Thornton, D Camburn. The life history calendar: a technique for collecting retrospective data. Sociological Methodology. 18: 1988; 37–68.

- WG Axinn, LD Pearce, D Ghimire. Innovations in life history calendar applications. Social Science Research. 28: 1999; 243–264.

- A Caspi, TE Moffitt, A Thornton. The life history calendar: a research method and clinical assessment method for collecting retrospective event-history data. International Journal of Methods in Psychiatric Research. 6: 1996; 101–114.

- RF Belli. The structure of autobiographical memory and the event history calendar: potential improvements in the quality of retrospective reports in surveys. Memory. 6(4): 1998; 383–406.

- T Barreto, O Campbell, JL Davies. Investigating induced abortion in developing countries. Studies in Family Planning. 23(3): 1992; 159–170.

- D Huntington, B Mensch, VC Miller. Survey questions for the measurement of induced abortion. Studies in Family Planning. 27: 1996; 155–161.

- S Johansson, O Nygren. The missing girls of China: a new demographic account. Population Development and Review. 17(1): 1991; 35–51.

- Financing, provision and utilization of reproductive health services in China. Research report prepared by Kunming Medical College; Shanghai Medical University; Abt Associates; Institute for Development Studies, University of Sussex for Ford Foundation, 1997.

- MJ Graham, U Larsen, XP Xu. Son preference in Anhui Province, China. International Family Planning Perspectives. 24(2): 1998; 72–77.

- M Das Gupta, SZ Li. Gender bias and marriage squeeze in China, South Korea and India 1920–1990: the effects of war, famine and fertility decline. Development and Change. 30(3): 1999; 619–652.

- RoundtableReproductive Health Matters. 10(19): 2002; 194–197.