Abstract

Before modern contraceptive methods were available in developing countries, post-partum sexual abstinence formed the backbone of birth spacing. With the changes occurring in African societies, how has post-partum sexual abstinence been affected? We conducted an exploratory study in 2000–2001 in Abidjan, Côte d'Ivoire with 23 women and 19 men who were parents of small children. Breastfeeding remains widespread and prolonged. Resumption of sexual relations after delivery was a mean of 11 months. Post-partum sexual abstinence was only distantly related to the traditional lactation taboo. Women expressed fears that their partner would seek elsewhere if they delayed sexual relations too long, and the risk of early pregnancy. Abstinence remained the main way to space births, given low contraceptive use. Mothers generally decided when to wean a child. Men usually made the first move to resume sexual relations, though most women negotiated timing and some insisted on condom use. Provision of condoms post-partum can play a contraceptive role for married couples and protect against STIs/HIV in extra-marital relationships, which are frequent post-partum. The duration of post-partum abstinence is in fact unclear because irregular sex may happen early and become regular only later. Women need post-partum information and services that address these issues.

Résumé

Avant l'apparition de la contraception moderne dans les pays en développement, l'abstinence sexuelle post-partum était la principale méthode d'espacement des naissances. Comment l'évolution des sociétés africaines a-t-elle influencé cette abstinence ? En 2000–2001, nous avons interrogé à Abidjan, Côte d'Ivoire, 23 femmes et 19 hommes parents de jeunes enfants. L'allaitement demeure fréquent et prolongé. La reprise des relations sexuelles se produit en moyenne 11 mois après l'accouchement. L'abstinence post-partum n'est pas directement liée au tabou traditionnel de lactation. Les femmes craignent que leur partenaire s'éloigne si elles tardent trop à reprendre les rapports et elles redoutent une grossesse précoce. L'abstinence demeure la principale méthode d'espacement des naissances, car les contraceptifs sont peu utilisés. En général, les mères décident du moment du sevrage. Les hommes prenent habituellement l'initiative de la reprise des rapports sexuels, même si la plupart des femmes avant négocié le moment et si certaines demandent un préservatif. La distribution de préservatifs après l'accouchement peut avoir un rôle contraceptif pour les couples mariés et protéger contre les IST/VIH dans les relations extraconjugales, fréquentes après un accouchement. La durée de l'abstinence est peu claire car des rapports irréguliers peuvent intervenir rapidement après l'accouchement pour se régulariser plus tard. Les femmes ont besoin d'informations et de services post-partum sur ces questions.

Resumen

Antes que existieran métodos anticonceptivos modernos en países en desarrollo, la abstinencia sexual posparto era el eje del espaciamiento de nacimientos. Con los cambios que están ocurriendo en las sociedades africanas, cómo ha sido afectada la abstinencia sexual posparto? Llevamos a cabo un estudio exploratorio en 2000-2001 en Abidjan, Costa de Marfil, con 23 mujeres y 19 hombres, quienes eran padres de hijos pequeños. La lactancia continãa practicándose de manera extendida y prolongada. La reanudación de las relaciones sexuales después del parto fue de 11 meses en promedio. Se encontró una relación distante entre la abstinencia sexual posparto y el tabú tradicional de lactancia. Las mujeres expresaron temores de que su pareja podría buscarse a otra si ellas postergaban las relaciones sexuales por mucho tiempo, y del riesgo de quedar embarazada a temprana edad. La abstinencia continuó siendo la forma principal de espaciar nacimientos, dado el bajo uso de anticonceptivos. En general, las madres deciden cuando dejar de amamantar. Los hombres, por lo general, dan el primer paso para reanudar las relaciones sexuales, aunque la mayoría de las mujeres negocian el momento adecuado y algunas insisten en el uso de condones. El suministro de condones posparto puede desempeñar un papel anticonceptivo para las parejas casadas y proteger contra las ITS/VIH en relaciones extramaritales, que son frecuentes posparto. Se ignora la duración exacta de la abstinencia posparto pues, al inicio, las relaciones sexuales pueden ser irregulares y sólo después volverse regulares. Las mujeres necesitan información y servicios posparto que traten estos aspectos.

The traditional practice of long post-partum sexual abstinence in African societies and its role as a means of fertility regulation have been well described in studies in the 1980s. In predominantly agricultural societies, post-partum abstinence was a way to ensure a balance between women's dual functions as procreators and agricultural producers through long birth intervals (about three years) and at the same time to safeguard the health of the woman and her children. The main rule governing post-partum sexual abstinence was the “lactation taboo” – as long as a woman was nursing her child she must not resume sexual relations. This abstinence period lasted until the child was weaned at two years of age or so. Sexual abstinence for couples during those two years was possible in a polygynous context where separation of spouses was frequent, particularly after childbirth, and where society favoured the “physical and emotional” separation of married couples.Citation1 Before modern contraceptive methods were introduced or available in developing countries, post-partum sexual abstinence formed the backbone of birth spacing. With the changes occurring in African societies and the advent of family planning programmes, how has this practice been affected? Polygyny is less frequent in Africa, and conjugal bonds are tighter. In cities, nuclear families are increasing, social control is weaker given less co-residence with parents and in-laws, and physical separation of spouses after childbirth has become rare. In the 1990s, a study in the Gambia found that abstinence patterns varied but were influenced by social norms.Citation2 Demographic surveys in several countries in West Africa still show long durations of post-partum sexual abstinence. The mean duration was estimated to be 12 months in Côte d'Ivoire in 1997,Citation3 16 months in Burkina Faso in 2003Citation4 and 9 months in Ghana in 2003.Citation5

This paper is about the persistence of post-partum sexual abstinence today and how it has been adapted in Abidjan, Côte d'Ivoire, a city of three million inhabitants and an important economic centre for West Africa. Household organisation has undergone many changes in Abidjan in recent years, and there is evidence of a decrease in polygyny and an increase in nuclear families,Citation6 probably affecting gender relations. In spite of the development of family planning programmes, and even though modern contraceptive use is rising, overall contraceptive prevalence remains low. The latest Demographic and Health Survey in 1998–99Citation3 reported a modern contraceptive prevalence rate for women living in union of only 12%. Moreover, Côte d'Ivoire is widely affected by the HIV/AIDS epidemic with an estimated adult prevalence rate of about 10% in Abidjan.Citation7

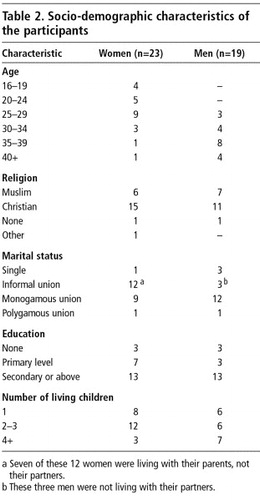

Data from the World Fertility Survey of 1980–81Citation8 and two Demographic and Health Surveys in Côte d'Ivoire in 1994 and 1998–99Citation3, Citation9 highlight the persistence of prolonged sexual abstinence following childbirth (), with little change between 1980 and 1999. In all three surveys, the median duration of sexual abstinence is lower than the median duration of breastfeeding, and about 50% of women have resumed sexual relations nine months after giving birth. In spite of this apparent lack of change over time, we asked whether post-partum abstinence has the same function today as it did 20 years before. Our aim was to understand how couples negotiate the resumption of sexual relations following childbirth, the role of post-partum sexual abstinence, the underlying norms, who makes the decision and what each partner's agency is in the decision.

Table 1 Median duration of post-partum sexual abstinence and breastfeeding during the last 20 years in Abidian, Cote d'Ivoire

Methods and participants

We carried out an exploratory qualitative survey between November 2000 and January 2001. Semi-structured interviews were undertaken using an interview guide with 23 women and 19 men, recruited from the waiting rooms of two urban health facilities in Abobo, a working class neighbourhood of Abidjan. To be included in the sample, both women and men had to be the parent of an already weaned child under the age of five. Women were selected from among the mothers waiting to have their children vaccinated, and men from among patients waiting for consultation or accompanying someone else. Every day for two weeks, the two or three first persons in each queue were enrolled if they consented.

Respondents were told that the survey aimed to improve knowledge of maternal and child health and that confidentiality and anonymity were ensured. There were no refusals. The female author of this paper interviewed the women and the male author the men in a separate room in the health facility. Spouses did not attend except in one case (a male patient was accompanied by his wife). Each interview lasted 45 minutes. The interview guide included questions on socio-economic characteristics, last-born child and his/her feeding patterns, date of weaning and how it was managed, information about the other parent, the desire to have another child following this last birth, whether or not contraception was being used, resumption of sexual relations following childbirth (timing and determinants), related norms, the respondent's views about resumption of sex and any negotiations with the partner on this issue. All the answers were handwritten during the interviews and later transcribed; analysis focused on relevant themes.

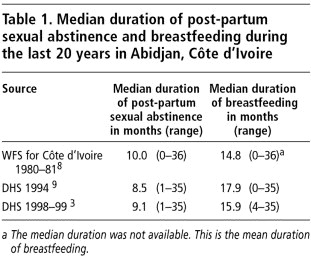

presents the socio-demographic characteristics of the respondents. All 11 major ethnic groups of Côte d'Ivoire are represented. The decline in polygyny in Abidjan is reflected in the sample, with only one man and one woman living in a polygynous union. Most respondents were living with their partners, either in a consensual union, legal marriage or marriage under customary law. The educational and occupational backgrounds of the respondents were in trade, crafts, dressmaking and hairdressing; some of the men were involved in white-collar jobs (data not shown).

Among the 23 women, the youngest child was 14 months old; all but three had resumed sexual relations at the time of the survey. Among the 19 men, the youngest child was six months old; all had resumed sexual relations at the time of the survey.

Results

The 42 interviews brought out similar trends to those shown in . Breastfeeding is widespread and prolonged, with a median of 15 months (range 6–30). Breastfeeding is not exclusive; complementary liquids are given at four months of age and complementary gruel and then the family meal at 5–6 months of age. The resumption of sexual relations after the last birth ranged from two months to two years with a mean of 11 months and a median of 10.5 months.

However, we discovered that there are different understandings of post-partum sexual abstinence. When asked “When did you resume sexual relations with your spouse?” respondents usually indicated the onset of regular sexual activities. When probed, it appeared that for some couples, post-partum abstinence meant completely abstaining from sexual relations; for others, it meant the absence of regular sexual activities despite having sex a few times. Among the women, four mentioned having had sex with their partners before the “official” date of resumption of sex. Similar evidence has been found in the GambiaCitation2 and Togo.Citation10 Thus, for some the resumption of intercourse becomes regular only after weaning but may also happen before it.

The reasons of the 42 respondents for waiting to resume sex were mainly articulated in terms of breastfeeding-related taboos, to protect the health of mother and baby, for birth spacing and in a few cases based on religious prescriptions.

Arguments for long post-partum abstinence

Semen and breastmilk must not mix

Nine women and eight men said they had resumed sexual relations only after complete cessation of breastfeeding. Resumption of sexual relations that took place only after weaning was associated with a shorter duration of breastfeeding and a longer duration of post-partum abstinence and often followed immediately after weaning.

The belief that having sex with a lactating woman is likely to be harmful for the nursing child and make it sick still exists in this population; eight women and six men articulated this view.

“It's not good to resume sexual relations when the child is suckling.”

“A man mustn't get near his wife while she's breastfeeding.”

“If a mother resumed sexual relations, her nursing child would fall sick just by touching her.”

Sexual relations in this view are believed to “poison” breastmilk. One man said it would trigger a “hormonal mechanism” that would cause a decline in the nutritive quality of breastmilk. The basis of this view, known in different societies and studied by anthropologists, is that sperm and breastmilk are incompatible.Citation11 There is a local name for the illness that a child can contract in this particular case. Among those who mentioned this taboo, some expressed great fear and respect for it, particularly young women with a first-born and those who were still living with their parents. One man with a degree in sociology said he followed this proscription very strictly.

For several of the men, the taboo on sex was limited to the period of “intensive breastfeeding”, i.e. as long as the infant was totally dependent on breastmilk. This concept is somewhat imprecise, insofar as complementary foods are introduced early and gradually in Côte d'Ivoire, but it implies a shorter period in which abstinence from sexual relations must be maintained than at weaning.

Wait until the child is able to walk

Five women and two men said that resumption of sexual relations depended on when the child was able to walk. Walking is a sign that the child has grown and is strong enough not to need breastmilk anymore, and is resistant to illness. Sometimes the belief that breastfeeding is incompatible with sexual relations and waiting until the child can walk overlapped. Thus, a woman who worried about poisoning her child through breastfeeding as a result of sexual relations, did actually resume sex before weaning but after her child had begun to walk.

Wait until the mother has recuperated from childbirth

The decision to resume sexual relations for more than a third of respondents (six women and ten men) was justified not by the child's health but to allow women to recuperate from delivery. This was described as a “minimum waiting period” that ranged from five to eight months or until the return of menses.

Even when respondents did not clearly refer to the return of menses, there appeared to be a marked trend to resume sexual relations once the woman got her menstrual period. Only seven of the 42 respondents had resumed sexual relations before that point. Their reasons were closely related to concerns about both fertility regulation and respect for the woman's health. Some women considered that once they got their menstrual period, they could “follow their cycle” and prevent pregnancy by avoiding unprotected sex during their fertile days. Moreover, those who wanted to use modern contraception also had to wait until the return of menses. They followed the recommendations of family planning services to come for a consultation as soon as they got their menstrual cycle.Citation12 The men saw the return of menstruation as a sign that the woman's body had recuperated from delivery, and thus she was ready to resume sexual relations.

Incompatibility between nursing and a new pregnancy

There was general agreement among these respondents about the incompatibility of breastfeeding with a new pregnancy. All respondents reported that as soon as a breastfeeding woman realises she has begun a new pregnancy, she must wean her nursing child completely. One said that the milk becomes bad and another that the milk “becomes warm and gives the child diarrhoea”.

Islamic custom

Although Islam is one of the main religions in Côte d'Ivoire (one third of Ivorians are Muslims), the Islamic prescription of 40 days of post-partum abstinence was mentioned only by two men. One of the two resumed sexual relations accordingly. The other said the custom was to have one encounter 45 days after childbirth and then wait until the return of menses to resume regular sexual activities.

Bledsoe identified a similar custom in the Gambia in a predominantly Muslim population,Citation2 that the couple should have sex on the 40th day after childbirth, which is important as it is supposed to protect the couple against a new pregnancy, after which the resumption of sexual activity depended upon the couple's personal constraints and decision.

Early resumption of conjugal sex

Although the mean duration of post-partum abstinence was 11 months, one respondent resumed sex two months after childbirth and more than 25% of respondents had resumed sex by six months after childbirth. Thus the breastfeeding taboo was not always followed: 13 women and nine men resumed sex before weaning. One young woman, single and 16 years old, was “unaware of rules” and clearly suffered from a lack of education and information on sexual matters.

For many others, the decision about when to resume sex was above all the private concern of the couple and did not concern anyone else. Only five of the 23 women had talked about it with a sister (1), mother (2) or friend (2). They said that peers (friends, sisters) had made no mention of the incompatibility between breastfeeding and the onset of sexual relations; instead, they talked about the risk of a husband's unfaithfulness if resumption of sex was delayed and the risk of pregnancy if it was too early. The involvement of the older generation was very limited. One mother advised her daughter to resume sex after weaning; the other mother advised use of condoms and this woman resumed sex three months after childbirth with condoms. The men never sought advice from family members or friends.

However, one woman pointed out that although the couple were free to decide when to resume sex, it was the woman who would be blamed if birth intervals were too short. Birth spacing is considered women's responsibility all over sub-Saharan Africa.Citation1

Taking the partner's wishes into account

Women felt it was necessary to take their husbands' desires into account, as illustrated by one woman who resumed sexual relations with her husband six months after delivery, without having weaned her child:

“According to our grandparents' sayings, milk is spoiled when sexual relations are resumed. Today, however, we must resume earlier because the husband does not want to wait. He has nowhere else to go.”

The decision when to wean a child is generally made by the woman; the man is usually the one to make the first move to resume sexual relations.Footnote* All the women said that men were the initiators of the resumption of sexual relations, and eight of them said they felt compelled to do so earlier than they would have liked, in order to prevent their partners from seeking sex elsewhere. A number of women said that in polygynous marriages in the past, post-partum abstinence for each woman could be longer as married men turned to their other wives. With monogamous marriages, men found extra-marital partners, with emotional consequences for the wife and increased health risks in a country widely affected by the HIV epidemic.

One woman, age 42, said that she had always resumed sex around four months after the birth of each of her eight children. Most of the women, regardless of age and birth cohort, expressed the fear of extra-marital sex, HIV and others sexually transmitted infections in more or less veiled terms.

“Today, we are compelled to comply with our husband's wishes because if you refuse to resume encounters, he will seek elsewhere and is likely to bring the illness back to his wife.”

“When you love your husband, you don't want to see him seek elsewhere.”

The women's fears were well-grounded. Of the 19 male respondents, ten reported having sexual relations with partners other than the mother of their child before resuming sex with her. Among the nine others, some did not wish to answer this question at all. Thus, extra-marital sex on men's part seems quite common alongside post-partum sexual abstinence, and this involves not only men whose wives abstained for long periods after childbirth but also those who resumed sex a few months after childbirth. This has also been described in other sub-Saharan countries.Citation13

Confronted with the dilemma, it seems that most women did have the agency to negotiate. Many delayed resumption of sexual relations by at least a few months after their husband's request, usually on the pretext of the child's health. Some waited until they weaned the child, others until the child could walk. Some only delayed for a short time (a month, for example), in order “to let the child grow a little more”. The timing was not in fact grounded in any particular event. One woman said that she had refused to resume sex at first but finally agreed as her husband was “begging” her.

Moreover, some women agreed to resume sex only if it was protected. There was one woman who was approached by her husband to resume sex a few months after childbirth who also refused at first and finally agreed, providing that they used condoms. Indeed, when sex precedes weaning, the use of condoms allows the traditional taboo regarding semen and breastmilk not to be broken as well.

There were also some cases where the resumption of sex was part of wider negotiations between the couple. At the time of the survey, two women were discussing this with their partners. For the one, resumption of sexual relations depended on a larger commitment from her partner to support her and their child. The other wanted her “marital status” to be clear; she refused to resume sex unless her partner broke with another woman.

Other traditional strategies were also used. Two women went to live with their mothers during the year following childbirth and resumed sexual relations when they went back to live with their husbands. A young girl still living with her parents avoided spending the night at her partner's house as long as she did not wish to resume sex.

On the whole, female respondents seem to have had some power of negotiation within their relationships concerning the resumption of sex. However, in the absence of negotiations, wives consented to the demands of their husbands.

Resumption of sexual relations and risk of early pregnancy

There is evidence that women seldom resume sex before the return of menses, in order to be able to avoid the risk of becoming pregnant again. At the same time, as they stop breastfeeding abruptly if they become pregnant, they aim to resume sex only when the baby is considered strong enough to be weaned without danger.

Women's fear of becoming pregnant too soon is related to the lack of effective fertility control methods, particularly in the immediate post-partum period. At the time of the survey, only 10 of the 42 respondents were contraceptive users: three used condoms regularly and seven women were taking the pill. The others (male and female) were “following the woman's cycle” and abstained or used condoms during her fertile days. Yet, most of the respondents said they were interested by modern contraception. Some had attended for family planning services but did not continue because they had moved or lacked money. Others asked for more information about family planning. However, in general, we noted reluctance with regard to modern contraception and suspicions about hormonal methods causing weight gain, amenorrhoea, various illnesses and infertility. Several young women also mentioned their mother's opposition to contraceptive use.

Other surveys, specifically on family planning, in Côte d'Ivoire found a similar reluctance. Côte d'Ivoire did not adopt a national population policy until 1997;Citation14 services and information were very limited in the late 1990s and the contraceptive prevalence rate very low. Reported use of modern methods among women living in union was only 12% in Abidjan and 7% for the country as a whole in 1998. Provision of contraception was particularly inadequate for post-partum women, and was not offered before return of menstruation.Citation12 That is why most women waited until they got their menses to resume sex, whatever form of contraception they then used.

Discussion and recommendations

This study shows that a long period of post-partum abstinence remains common in Abidjan, with a mean duration close to the child's first birthday. However, today the practice is only distantly related to the traditional taboo on mixing sexual relations with breastfeeding. While resumption of sex usually precedes weaning, the rule was and still is expressed in terms of avoiding “too early” resumption of sexual relations.

Behind the persistence of prolonged sexual abstinence following childbirth, this study highlights the fear of too early pregnancy as harmful for both infant and mother. Thus, post-partum abstinence today seems to be, above all, a traditional way to space births and is closely associated with low contraceptive prevalence rates, especially among post-partum women. Nevertheless, in this modern cultural setting, affected by the decrease in polygyny (at least officially), long periods of sexual abstinence create the risk that men will seek sex elsewhere, with the risk that they and their partners will get an STI or HIV.

Family planning providers should begin to offer women information and services in the post-partum period that addresses these inter-related issues. First, women and their partners should be reassured that they can resume sex while breastfeeding without harming the child. Moreover, they should have access to the means to prevent pregnancy so they can resume sexual activity when they are ready, without having to wait for the return of menses or stopping breastfeeding. Lastly, where condom use is low, as in Côte d'Ivoire,Citation15 discussion of HIV prevention and provision of condoms should be strengthened following a birth, using a “couple approach” rather than an individual one. Provision of condoms to couples post-partum can play a threefold role: a contraceptive role for married couples where there are still negative perceptions of hormonal contraceptives, a means of protection against STIs and HIV in extra-marital relationships, which are frequent during the post-partum period,Citation13 and to bypass the lactation taboo in cases where it persists.

Lastly, it is important to get a greater understand of the post-partum period, which is a very vulnerable time for the mother. Having just delivered, she is not fertile or sexually active and is nursing her child. Then, she becomes fertile again, resumes sexual relations and weans the child. Her sexual and reproductive health and the way she copes with motherhood will depend on how she and her spouse – if she has a spouse - experience these events. Yet, the post-partum period is not well documented. It turns out that even the duration of post-partum abstinence is unclear because the meaning of “resumption of sexual relations” may mean when the couple has had sex once or twice, followed by a long interval, or when regular sexual activity begins again. Thus, from a family planning point of view, it is unclear how soon most post-partum women are actually at risk of pregnancy.Citation16 It would be helpful if Demographic and Health Surveys would gather more precise information on these points, so that services for women can be more accurately based on their needs.

Acknowledgements

This article is based on a paper in French delivered as an oral communication at the 24th General Conference of the IUSSP (International Union for the Scientific Study of Population) in Salvador de Bahia, Brazil, 18-24 August 2001. The text in French is available at: ⟨www.lped.org⟩. We would like to thank Michel Bozon, who asked us to prepare this paper for the session on “Sexuality” at the conference and gave us valuable advice on the first draft. We also acknowledge Florence Waitzenegger-Lalou, who did the translation from French to English.

Notes

* In this study, none of the women mentioned whether their own sexual desires were taken into account in the decision to resume sex. We do not know whether this is because the women were reluctant to talk about their sexual desires or because men's sexual needs always take precedence over women's.

References

- E Van de Walle, F Van de Walle. Les pratiques traditionnelles et modernes des couples en matière d'espacement ou d'arrêt de la fécondité. In: Tabutin D, editor. Population et Société en Afrique au Sud du Sahara. 1988; L'Harmattan: Paris, 141–166.

- C Bledsoe Basu, A Hill. Social norms, natural fertility, and the resumption of postpartum “contact” in the Gambia. AM, P Aaby. The Methods and Uses of Anthropological Demography. 1988; Clarendon Press: Oxford, 268–297.

- Institut National de la Statistique (Côte d'Ivoire), ORC Macro. Enquête démographique et de santé, Côte d'Ivoire 1998–1999. 2001; INS, ORC Macro: Calverton MD.

- Institut National de la Statistique et de la Démographie (INSD), ORC Macro. Enquête Démographique et de Santé du Burkina Faso 2003. 2004; INSD, ORC Macro: Calverton MD.

- Ghana Statistical Service, Noguchi Memorial Institute for Medical Research, ORC Macro. Ghana Demographic and Health Survey 2003. 2004; GSS, NMIMR, ORC Macro: Calverton MD.

- Recensement Général de la Population et de l'Habitat, Côte d'Ivoire. Analyse des résultats définitifs. 1988; Institut National de la Statistique: Abidjan.

- C Sakarovitch, P Msellati, L Bequet, . HIV prevalence and incidence among pregnant women in Abidjan, 1995–2002. XIIIème Conférence Internationale sur le Sida en Afrique, Nairobi. 21-26 September. 2003, Résumé TuePs397727.

- Direction de la Statistique, Ministère de l'Economie et des Finances. Enquête Ivoirienne sur la Fécondité 1980–81. Rapport principal. Vol.1. Analyse des principaux résultats. 1984; Direction de la Statistique, World Fertility Survey: Abidjan.

- S N'Cho, L Kouassi, K Kouamé. Enquête démographique et de Santé, Côte d'Ivoire, 1994. 1995; Institut National de la Statistique, Macro International: Calverton MD.

- T Locoh. Fécondité et famille en Afrique de l'Ouest. Le Togo méridional contemporain. 1984; INED, Travaux et Documents, Cahier n° 107: Paris.

- F Héritier. Masculin / Féminin. La Pensée de la Différence. 1996; Ed. Odile Jacob: Paris.

- A Guillaume. Desgrées-du-Loû A. Fertility regulation among women in Abidjan, Côte d'Ivoire: contraception, abortion or both?. International Family Planning Perspectives. 28(3): 2002; 159–166.

- J Cleland, M Ali, V Capo-Chichi. Post partum sexual abstinence in West Africa: implications for AIDS control and family planning programmes. AIDS. 13: 1999; 125–131.

- Ministère chargé du Plan et du Développement Industriel. Déclaration de Politique Nationale de Population, République de Côte d'Ivoire, FNUAP, mars. 1997.

- B Zanou, A Nyankawindemera, JP Toto. Enquête de Surveillance de Comportements Relatifs aux MST/SIDA en Côte d'Ivoire (BSS Octobre 1998). Rapports. 1999; ENSEA, Impact, USAID, SFPS: Abidjan.

- A Desgrées-du-Loû, M Ferrand Lelièvre, H Brou. Sexualité/fécondité: transitions autour de la grossesse. E, P Antoine. Le Passage des Seuils, Observation et Traitement du Temps flou. 2005; INED, Coll. Méthodes et Savoirs: Paris. (Forthcoming).