Abstract

Norway has a long history of good reproductive health care, with some of the world's best reproductive health indicators. Early reduction of maternal mortality, good services for abortion, contraception and sexually transmitted diseases, a low rate of adolescent pregnancies and a low number people with HIV are examples, achieved through an integrated, publicly provided and funded health care package. Official Norwegian development assistance started in 1952. Emphasis on family planning assistance dates back to 1966, making Norway one of the most consistent donors to family planning and reproductive health programmes. Norway also had a high profile at the International Conference on Population and Development and strongly supported the Programme of Action. Since then, while multilateral support in these areas has stayed high, bilateral support has been downscaled. Overall, international assistance does not reflect the domestic approach to reproductive health services. Norway has given little development support to improvement of maternity services, avoided the issues of abortion and post-coital contraception, and passed up opportunities to support adolescent services. Prevention and treatment of infertility has hardly been an issue. Revitalisation of the reproductive rights discourse in Norway could provide a basis for the protection of reproductive health care domestically, and for policy discussions and decisions in relation to Norway's development assistance.

Résumé

La Norvège dispose depuis longtemps de bons soins de santé génésique, avec certains des meilleurs indicateurs du monde – mortalité maternelle réduite, bons services d'avortement, de contraception et de lutte contre les MST, faible taux de grossesses des adolescentes et nombre peu élevé de séropositifs – obtenus avec un système de soins intégrés, assurés et financés par le secteur public. L'aide publique au développement (APD) de la Norvège a commencé en 1952. La priorité à la planification familiale date de 1966, faisant de la Norvège l'un des donateurs les plus stables des programmes de planification familiale et de santé génésique. Elle a également participé activement à la Conférence internationale sur la population et le développement, et a soutenu son Programme d'action. Depuis, si elle maintient son soutien multilatéral dans ces secteurs, elle a réduit son appui bilatéral. Globalement, l'APD ne reflète pas l'approche nationale des services de santé génésique. La Norvège a peu soutenu les services de maternité, évité la question de l'avortement et de la contraception post-coïtale, et laissé passer les occasions d'appuyer les services pour adolescents. La prévention et le traitement de la stérilité n'ont guère été évoqués. La revitalisation du discours sur les droits génésiques en Norvège pourrait servir de base à la protection des soins de santé génésique au plan national, et à des débats et des décisions sur l'APD de la Norvège.

Resumen

En Noruega existe una larga historia de buenos servicios de salud reproductiva, que cuenta con algunos de los mejores indicadores de salud reproductiva del mundo – la disminución temprana de la mortalidad materna, buenos servicios de aborto, anticoncepción y enfermedades de transmisión sexual, una baja tasa de embarazos adolescentes y un bajo índice de VIH – logrados mediante un paquete integrado de atención a la salud suministrado y financiado pãblicamente. Noruega, uno de los donantes más constantes a los programas de planificación familiar y salud reproductiva, comenzó su asistencia al desarrollo en 1952 y su asistencia a la planificación familiar en 1966. Además, ocupó un lugar destacado en la Conferencia Internacional sobre la Población y el Desarrollo, y apoyó enfáticamente el Programa de Acción. Desde entonces, aunque se ha continuado brindando mucho apoyo multilateral a estas áreas, el apoyo bilateral ha disminuido. En general, la ayuda internacional no refleja el enfoque nacional hacia los servicios de salud reproductiva. Noruega ha brindado poco apoyo para mejorar los servicios de maternidad, evitó los temas de aborto y anticoncepción poscoito y desperdició las oportunidades de apoyar los servicios de adolescentes. La revitalización del discurso de los derechos reproductivos en Noruega podría proporcionar el fundamento para proteger a los servicios nacionales de salud reproductiva y deliberar sobre las políticas y decisiones relacionadas con la asistencia al desarrollo en Noruega.

This paper outlines some of the policy issues related to the development of reproductive health care in Norway and discusses whether national policy has influenced the way in which Norway acts as a donor in the area of population and reproductive health. Ideally, a country's policies as a donor and at home should be closely linked, but there are complex processes involved, which are deeply embedded in political, cultural and socio-economic realities, involving many actors, paradoxes and compromises.

A short description of Norway's reproductive health policies

Reduction of maternal mortality, provision of maternity services

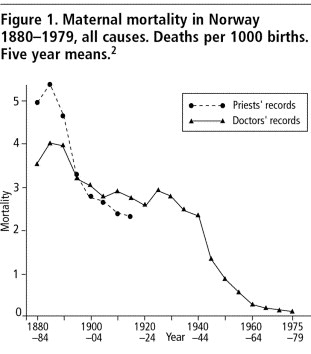

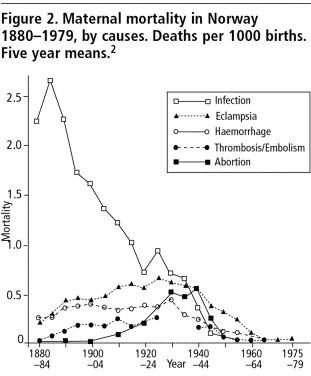

Together with the other Nordic countries and the Netherlands, Norway was a pioneer in reducing pregnancy-related mortality, even when compared to other developed countries such as the US and UK.Citation1 Documentation charting the history of the reduction in deaths is reasonably reliable. Two kinds of records of deaths were kept, those by doctors, in which causes of death are listed, and those of priests, in relation to the task of performing funerals.Citation2 shows that the two data sets have the same pattern. In 1880, the maternal mortality ratio was approximately 500 deaths to 100,000 live births; in 1979 it had dropped to about 10 to 100,000. About half of the reduction took place as early as the years 1885–1905 and was due to a drop in deaths from sepsis (see ). As the case–fatality rate for sepsis had hardly changed, the change in mortality can be attributed to prevention of infection rather than treatment. Infection-related mortality continued to drop, and from 1940 onwards a reduction was also seen in mortality from other causes ().

Figure 1 Maternal mortality in Norway 1880-1979, all causes. Deaths per 1000 births Five year means.Citation2

Figure 2 Maternal mortality in Norway 1880-1979, by causes. Deaths per 1000 births Five year means.Citation2

Some of the important reasons for this early reduction in maternal deaths relate to how the medical profession took shape in Norway, and the fact that when hospitals started to be built around 1800, obstetric care and delivery wards were prioritised. The purpose of institutionalising births was to educate midwives to work in the rural areas and to deliver poor women. The delivery clinics were crowded, however, and were often unhygienic with high fatality rates, much higher than for home deliveries. Sepsis was called “wound fever” or “poison fever”. Various explanations were given for the causes, including judgemental ones about the moral standards of the women.Citation3

Traditional birth attendants supervised by clergy were subsequently replaced by midwives.Citation4 In 1810, a law was introduced that made it mandatory to use trained midwives at deliveries where they were available. Both traditional birth attendants and delivering women could face criminal charges if they did not comply.Citation5 Coverage by midwives was given high priority; local authorities were required to send women for midwifery training and, if necessary, had to cover the cost of their education. The number of midwives increased nationally from 50 in 1810 to 500 in 1860.Citation3

The importance of midwifery was thus acknowledged early on. Midwifery was the first health profession to be regulated by the authorities, with the dual objectives of providing the best services for women and to secure the interest of the midwives.Citation6 Why this was the case is not clear. It appears that doctors were instrumental in pushing for the employment of midwives, however.Citation5 The reduction in pregnancy-related mortality among the Nordics and in the Netherlands is generally explained by the fact that midwives, not doctors, handled normal deliveries.Citation1

The Norwegian maternal mortality ratio is presently one of the lowest in the world. Data for 1980 to 2000 from Statistics Norway show that there have been 0–5 maternal deaths per year. In the 1980s the ratio was 3.5 to 100,000 live births and 4.6 in the 1990s, with hypertensive complications the most common cause of death. It is uncertain whether it is possible to substantially reduce maternal mortality any further.Citation7 Antenatal care is universal and is provided by general practitioners and midwives free of charge. Deliveries are also totally free of charge. The institutional delivery rate is almost 100%, with a system of partially decentralised maternity centres and emphasis on provision of adequate transport to secure care at the right level.

Abortion services

The history of abortion in Norway is similar to that of many other developed countries. A 1687 law did not distinguish between abortion and infanticide, and punished both with the death penalty.Citation8 Capital punishment was abolished in 1842 and replaced with hard labour and later with imprisonment.Citation9 The Penal Code of 1902 stipulated three years' imprisonment for women having an illegal abortion; this law lasted until 1964.Citation8 During the years that it was in force, it was possible to obtain a legal abortion if a doctor believed it was justified, based on unclear and subjective criteria.Citation10 The death toll from illegal abortions compared to other maternal causes is illustrated in ; recorded deaths were particularly high around 1940–45. It is, however, believed that this is due to more accurate recording during those years than to actual increase.Citation2

A law separate from the Penal Code was adopted by parliament in 1960 and came into force in 1964. It called for hospital medical committees to decide all individual cases. The present abortion law was passed in 1979, allowing abortion on demand during the first 12 weeks of pregnancy and by the decision of a medical committee over 12 weeks. The 1979 legislative changes reflect internal struggles and debates, as in other European countries in the 1960s and 70s. The main arguments for those who wanted to liberalise the law were documented morbidity and mortality from illegal abortions, and particularly how this affected women living in poverty.Citation11 A study in 1973 documented social biases and geographical differences in the decisions of doctors and medical committees as to whether a legal abortion should be granted.Citation12 In addition to researchers, NGOs were instrumental in preparing the ground for legislative changes, as were government officials in central positions.Citation13 The main political parties are presently discussing the possibility of extending the 12-week time limit to 16 weeks, and this may become an important issue in the parliamentary election coming up in September 2005.

When abortion on demand was introduced, it was claimed that abortion rates might rise. This did not happen. The abortion rate for the total population of women aged 15–49 was 12.6 in 2002. While there have been fluctuations, the overall trend has been downward. Abortions among young women have been followed with special interest. In general, there are few adolescent pregnancies. Abortion rates among adolescents have dropped from 21.0 per 1,000 girls in 1982 to 16.9 in 2002. Very few adolescent girls become mothers in Norway; more than 6 out of 10 adolescent pregnancies now end in abortion. Parallel to this, the age of sexual debut for girls has gone down by one year over the past ten-year period, and is presently 16.7 years of age. It may therefore be concluded that the policies and programmes geared towards preventing unwanted pregnancies among adolescents have been a success.Citation14

Contraception

In 1924, the first clinic offering advice related to sexuality and childbearing was opened in Oslo, and in the years that followed, similar clinics were started elsewhere.Citation15 NGOs and the labour movement were behind many of the clinics. In the beginning, little modern contraceptive technology could be offered, but the clinics were important places for women who sought information, help and support. The existence of the clinics raised the issue of sexuality in relation to power and gender in a very practical manner, and they were important for education of the general public and in the political discourse. They carried out important documentation and advocacy work, particularly in relation to how women became worn out by frequent pregnancies (“exhausted mothers' syndrome”). They were also concerned with young women in cities who were working in factories or as domestic servants.Citation11

When an increasing variety of modern contraceptives became available after 1960, there was already a tradition of family planning counselling in the country. Both the authorities and the professional associations were instrumental in making sure that contraceptive services became fully integrated in primary health care early on, in addition to being part of the gynaecology and obstetrics services. There was full coverage of publicly funded general practitioners, who were given handsome financial incentives for contraceptive counselling.

A few Norwegian NGOs run some model clinics for adolescents in addition to the ordinary health care system. From 1999 condoms provided to young people under the age of 20 have been free of charge. This was introduced as part of the national action plan to reduce unwanted pregnancies and the need for abortion, and the strategy to reduce HIV and sexually transmitted infections. In addition, from 2002 onwards, oral contraceptives are also free of charge to women under 20, by parliamentary decision. Norway was also one of the first countries in the world to allow post-coital contraception to be sold over the counter in 2000.

Some other reproductive health issues

Norway was a pioneer in introducing in-vitro fertilisation treatment in public hospitals. This policy has been constantly challenged, and many attempts have been made to restrict these services only to specific groups. There have been two rounds of laws on reproductive technology to date. In the first set, only married couples could be treated, and gamete donation was seriously restricted. In the second round treatment is permitted for cohabiting, infertile couples, and freezing of eggs and embryos is permitted. Egg donation is still prohibited, however. Sperm donors may no longer be anonymous, according to the revised Biotechnology Act.Citation16

Patients with sexually transmitted infections have for several decades been exempted from charges for consultations, and are given free medication. When HIV became an issue in Norway in the 1980s, it was at first predominantly among men who had sex with men and the health authorities invited gay activist organisations to collaborate on strategies. A few of the activists feared that the focus on HIV might re-introduce stigma against them, but they were outnumbered by those who felt the need to tackle this new challenge head-on. Good co-operation between the health authorities and gay activist groups has proved to be of the utmost importance, and their concerted efforts are believed to be the reason why the country has a much smaller HIV epidemic than predicted in the 1980s. Routine screening for HIV has been carried out in antenatal clinics since 1987.Citation17

Reproductive rights

In the struggle for liberalisation of the abortion law, both politicians and NGOs stressed rights issues. Reproductive rights have been prominent mainly during two historical periods.Citation18 The first was from 1913 to 1930. Women got the right to vote in 1913, and in 1915 the Children's Acts were adopted by parliament. The parliamentarian who pushed the laws, and whose name they carried, Johan Castberg, was the brother-in-law of the most prominent activist for abortion rights at the time, Katti Anker Møller. The Children's Acts gave children the right to inherit and to carry their father's name regardless of the marital status of their mother. This was important for improving the situation of both children and their mothers. The fight for the rights of children went hand in hand with the fight for abortion rights.

After 1930 the medical profession, lawyers and a few politicians dominated the abortion debate. Women's NGOs comprised a mixture of Christian organisations, housewives' organisations and more rights-based groups, and were divided over the abortion issue for a long period of time. The second period, in the lead-up to the legislative changes was 1960 to 1978, when feminist groups became stronger and more united.Citation18

Universal access to contraception services, including for the young and unmarried, has been uncontroversial since rather far back in history. One example is from 1947, when the then Director General of Health, Karl Evang, suggested that mother and child health clinics should provide birth control education and methods for unmarried women. The protests by women's organisations were so fierce that the proposal was abandoned.Citation15

Right to long, paid parental leave and financial support for childcare are often seen as reasons for the relatively high fertility rate in Norway compared to other European countries. The total fertility rate is now 1.8, according to Statistics Norway. Shared maternity and paternity leave can be 10 months with full pay or 12 months with 80% pay and an additional cash subsidy until the child is three years old.

Overall, the picture in Norway is very favourable, but there are still challenges. The notion of the welfare state, which has a long and solid tradition in Norway, is presently being eroded. The introduction of extensive private health care services parallel to the public health system was unthinkable only a few decades ago. Now private health care is on the rise.Citation19

Although there have been two commissions assessing priorities in health care, no results emerged – apart from transferring public subsidy to private payment for sterilisation and in vitro fertilisation.Citation20 This was an extraordinary step. The success of reproductive health care in Norway is because society has taken responsibility for securing access, and bearing the cost. By privatising these services, the public health ethic has been undermined.

The right to infertility treatment has constantly been questioned in Norway, and strong political and religious forces have supported restriction of access. The Act on Biotechnology stipulates that only married women and women cohabiting with men in marriage-like relationships are eligible. The argument is that there is no right to have a child, and therefore no right to treatment. Norway has one of the more restrictive biotechnology laws in the world, and any form of surrogacy beyond sperm donation is prohibited.

There is also a vocal anti-choice movement. While no direct attacks are being made on the present abortion law, there are subtle attempts to undermine the trust in women's ability to make an ethical choice on termination of pregnancy. All pregnant women are offered one routine ultrasound screening at 17 weeks, despite controversy around the role of such screening. Occasionally, for medical indications, ultrasound examination is carried out earlier. A 2002 White Paper created uncertainty as to whether the doctor or the midwife should inform the pregnant woman of any abnormalities detected during an early ultrasound examination.Citation21 Such a restriction in the right to information would have required a change in the law regulating patients' rights. In the revised Biotechnology Act 2004, it is made explicit that women have a right to such information.Citation22

Norway as a donor for population and family planning

Policies 1966–94

Official Norwegian development assistance started in 1952, in a modest way.Citation23 Emphasis on family planning assistance dates back to 1966, at the recommendation of a high-profile commission, whose members were politicians from various parties and technical experts,Citation24 on the grounds that population growth hampered economic growth in developing countries. They called for collaboration with the authorities of recipient countries where there was popular support for limiting the number of children.Citation25 The commission was not unanimous in this regard. Conservative Party members and Christian Democrats felt that more experience should be sought before family planning was made a priority.Citation26

Two years later, in 1968, the Norwegian parliament decided that family planning should be a priority for development assistance. The Christian Democrats voted against, claiming that family planning could be seen as education for immorality and could violate the integrity of families and individuals.Citation24 Norad, the governmental development agency, allocated 10% of bilateral development assistance to family planning in 1970, the only area of development assistance to be allocated a percentage.Citation23 With hindsight, the driving force behind this decision has been interpreted as neo-Malthusian.Citation24

In 1971, the parliament supported a Norad policy proposal, first mooted in 1966, of “extended” family planning, i.e. as part of primary health care and with the aim of improving the health of mothers and children. This gained wide support.Citation24Citation25 Population policies were to be seen as health policies, not interventions to influence sexual behaviour. By reaching out to women with services for maternal and child health, it was expected that women would want family planning, which would eventually curb population growth. This approach proved able to overcome previous disagreements in parliament, though the policy was ambiguous and open to interpretation.Citation24

This policy lasted until 1994, and was superseded by a policy on reproductive health and rights, following the International Conference on Population and Development.Citation24

Norway and the International Conference on Population and Development

In the lead-up to the International Conference on Population and Development (ICPD) in 1994, Norway produced a national report outlining its population and development assistance policies. Although it did not make “the simplistic assumption that it is the size of population and its growth in itself that are harmful”, the report stressed the “seriousness of present population growth and the need to counteract the negative effects on the environment”. Gender issues were seen as important along with “strengthening the health of women as a value in itself, and not primarily as a means to reduce population growth”.Citation26

Norway had a high profile at ICPD and strongly supported the Programme of Action. The then Labour Party Prime Minister and later Director General of WHO, Dr. Gro Harlem Brundtland, gave a keynote speech on the opening day in Cairo that signalled Norway's support for the comprehensive approach to sexual and reproductive health outlined in the draft Programme. She expressed specific support for its most controversial parts – comprehensive reproductive health services, the rights of adolescents and abortion as a public health issue – and flatly rejected the allegation that it was promoting abortion.Citation27 During ICPD+5 in 1999, however, Norway had a coalition government, with the Christian Democrats holding the post of Minister of Development Assistance. While the government expressed continued support for the Programme of Action in general, they did not support emergency contraception as part of the UN-funded supplies and medicines package for refugee settings, a position that was criticised in the left-wing daily newspaper Klassekampen.

Bilateral vs. multilateral assistance before and after 1994

From 1972 to 1994 Norway gave bilateral support to India's Post-Partum Programme, a hospital-based family planning programme that was part of a wider effort aimed at stabilising population growth.Citation28 Norway was the programme's only international donor and contributed about 543 million Norwegian kroner (NOK) (6-7 NOK = 1 US$) in that period. In dialogue with the Indian authorities, Norway supported the principle of extended family planning and quality of care, with provision of family planning only to women who wanted it. The programme did utilise quotas, however, which are known to create undue pressure on the poor, both users and providers of the services.Citation28 A review carried out in 1990 was generally positive and recommended that funding be extended, despite diverging views on use of targets and incentives.Citation29 This situation thus reflects a classic donor dilemma, where there are disagreements on the ethics of a funded programme. The donor can still decide to continue support in order to influence and strengthen the aspects that are compatible with its own values and policies.

Bangladesh has also received Norwegian funds for population-related activities starting in 1975, motivated by the country's dense population and fast growth combined with severe poverty.Citation28 Norway was part of a consortium of donors led by the World Bank. Again Norway saw its role as a means to have a dialogue. There were concerns about the strong emphasis on sterilisation and on incentives and disincentives. While admitting there were problems in the programme, those within Norad who followed it closely claimed that it was possible to influence it. The fact that in 1986 Bangladesh stopped withholding salaries from providers who did not meet quotas, and revised the system of incentives and disincentives, are given as examples of donor influence.Citation28

Zimbabwe started receiving Norwegian support for its Family Health Project from 1986,Citation28 again with the World Bank co-ordinating the donors. The project was integrated in the primary health care system, with Zimbabwe providing more than 50% of the funds. Besides strengthening family planning services, it had a wider scope of improving the government's capacity in provision and management of reproductive health care, with a focus on improved access and quality of care. The Norwegian support went to infrastructure such as construction and rehabilitation of district hospitals and clinics, vehicles, development of educational material and training of personnel.

According to Population Action International, Norway was the only country prior to 1994 to allocate at least 4% of overseas development assistance to “population”.Citation30 Multilaterally, Norway has been one of the biggest donors to UNFPA since its inception in 1969,Citation27 and the support has continued to be steady and high.Citation31 Norway is also one of the major donors to the International Planned Parenthood Federation.Citation32 To the Special Programme of Research, Development and Research Training in Human Reproduction at WHO, Norway has been the third largest government contributor of funds from 1970 to 2003, surpassed only by Sweden and the United Kingdom.Citation33 Being a considerably smaller country than the other donors, with approximately 4.5 million inhabitants, this shows the high priority given to multilateral assistance in the area of population and reproductive health.

Since 1991 Norway has phased out its bilateral population assistance, however, and since 1994 has not reported any allocation to such programmes to the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD).Citation30 It has, however, funded a few reproductive health activities in Malawi, Mozambique and Uganda. In 2003, this support amounted to 47 million NOK for all three countries.Citation34 Compared to earlier decades, however, this figure is low.

Norway has supported activities on HIV/AIDS since 1986Citation28, which presently have a high and increasing priority in Norwegian bilateral and multilateral development cooperation.Citation35 HIV/AIDS is seen as a general developmental issue,Citation36 but the link to reproductive health is barely made explicit in the guiding documents.

There are a few NGOs that receive funds for work against female genital mutilation, and the Norwegian government has a specific workplan for this issue. There is also one umbrella NGO (www.fokuskvinner.no) that acts as the coordinator of affiliated Norwegian NGOs to fund work in developing countries on gender in development generally and reproductive health and rights specifically. Some of their affiliates have received support for efforts to push their governments to implement the ICPD Programme of Action.

Similar to other European donor countries, Norway intends to withdraw from vertical programmes and earmarked funding, and has embarked on supporting sector-wide approaches and general budgetary support, letting recipient countries themselves determine priorities.

Discussion

Norway's development towards its present state as one of the world's most successful countries in terms of reproductive health indicators has taken place within a wider context, where gender issues, socio-economic development and general health care are but a few of the important ingredients. Despite its successes in reproductive health, however, the start of an erosion of public health care that is presently seen, in which reproductive health is especially targeted, is of concern. While the right to reproductive health care does not seem to be threatened, this erosion is an illustration that what is gained always needs to be protected. It is a paradox, however, that the rights issue seldom comes to the surface, although a notion of rights underlies the provision of reproductive health services. Maybe the services are taken for granted. We suggest that a deeper understanding of reproductive rights might help protect elements of the services that come under stress.

Most decision-makers would like to believe that there is harmony between their domestic and international aid policies. Does this hold true for Norway? The early engagement in family planning in relation to development assistance was with India and Bangladesh, two countries that had a “population problem”, both in their own view and in the opinion of the world community. In both countries there have also been accusations of violation of the rights of individuals. Norad felt that Norway had been useful by influencing both programmes to strengthen protection of rights.

Norwegian White Papers on development assistance from 1991 and 1995 respectively specified that support to mother-and-child health care and family planning should increasingly be channelled through multilateral organisations, and that Norway should use its influence in those organisations' governing structures to promote Norway's own development policy.Citation37 Policy changes have also taken place in terms of bilateral support. According to a White Paper in 2004, Norway is now the country of the OECD that channels the highest proportion of its development assistance though NGOs. More than 80% of this support goes to Norwegian NGOs and their partners. The amount going to NGOs now exceeds the amount going through traditional bilateral assistance to countries.Citation38 Importantly, many of the Norwegian NGOs receiving funds are religious ones.

Compared to other donors, Norway was in the forefront in funding population activities prior to the ICPD. Furthermore, the policy of “extended family planning” from 1971 implied that provision of contraceptives should be seen in a wider health context, with an emphasis on quality of care and in the light of gender concerns. Both in bilateral and multilateral development assistance there are examples of Norway pushing controversial issues such as the rights of adolescents to sexuality education and reproductive health services.

Overall, however, we do not, in Norway's development assistance, see a full reflection of the integrated approach to reproductive health services that is behind the successes of reproductive health outcomes domestically. Norway has given little support to improvement of maternity services, including to maternal death reviews or audits, which are central in monitoring the quality of maternal health in Norway. Norway's development assistance has also generally avoided the issue of abortion, not even supporting treatment of complications of unsafe abortions. Easy access to post-coital contraception, another area where Norway has been a pioneer, has, as far as we are aware, not been an issue in bilateral dialogue. Moreover, there have been many more opportunities to support services for adolescents than have been utilised, and prevention and treatment of infertility in developing countries has hardly been an issue.

There may be multiple reasons for the low priority presently given to reproductive health in bilateral support. The justification for the early focus on population was two-fold: the importance both for health and for development more generally. A similar justification is used for supporting efforts against HIV/AIDS. Interestingly, we do not find similar justifications for reproductive health activities in Norway's development assistance policies.

There may also be political reasons for the low profile given to reproductive health bilaterally. Norway has had several changes of government, from Labour Party to coalition governments. In the coalition governments, the post of Minister of Development Cooperation has usually been filled by someone from the Christian Democratic Party, which officially disagrees with the present abortion law. The need for consistency in Norway's development assistance policies, even with changing governments, is acknowledged, but may be handled differently when it comes to bilateral and multilateral funding. In bilateral assistance, funds can be tracked much more easily than in the big multilateral organisations, and funding may more easily come under political stress.

Researcher Armindo Miranda, a member of the evaluation team of the Indian Post-Partum Programme in 1990, in a report in 1983, discussed the basis for Norway's involvement in India's Family Welfare programme.Citation39 While it became possible for the Norwegian Parliament to agree on the actual funding, there were serious underlying differences in motivation. Miranda also questioned whether Norway had sufficient technical and political expertise for such involvement and contrasted Norway with Sweden. Both countries have been pioneers in supporting family planning programmes, he said, but Sweden has shown a deeper understanding of the intricacies of these programmes politically, academically and within NGOs, which policymakers and administrators of development assistance could draw upon. A recent evaluation of Sweden's assistance to sexual and reproductive health and rights programmes confirms the unambiguous stand Sweden is taking on issues that are considered controversial for other donors, such as adolescent sexual health and abortion.Citation40 While Norway has also supported and protected such sensitive areas in its interaction with multilateral organisations, there seems to have been great reluctance to do the same bilaterally.

We believe that despite long term involvement in population activities and reproductive health globally, Norway has an limited base of political and academic expertise for ensuring its future commitments, and that there is a need for both expertise building and consolidation of existing expertise. The domestic reproductive health challenges could also benefit from similar strengthening of expertise. We see reproductive rights as a possible common denominator, with a potential for revitalising both the discourse on development assistance and the country's own reproductive health issues.

Acknowledgement

Our thanks to Dr Anne Alvik, former Director General of Health of Norway, for valuable comments.

References

- V De Brouwere, W Van Lerberghe. Safe Motherhood Strategies: A Review of the Evidence. 2001; Studies in Health Services Organisation and Policy: Antwerp.

- J Maltau, B Grünfeld. Mødredødeligheten i Norge 1880-1979. Et medisinsk-historisk tilbakeblikk. Maternal mortality in Norway 1889–1979. A medico-historic review Tidsskr Nor Lægeforen. 103(5): 1983; 522–525.

- P Børdahl. Eres den som æres bør. Navn i norsk gynekologi. Praising the one that deserves the praise. Names in Norwegian gynaecology. P Børdahl, MH Moen, F Jerve. Midt i livet. Norsk gynekologisk forening 1946–1996. At Mid-Life. Norwegian Gynaecological Association 1946–1996. 1996; Tapir: Trondheim.

- I Blom. Den haarde Dyst. Fødsler og fødselshjelp gjennom 150 år. The Hard Combat. Deliveries and Obstetrics through 150 Years. 1988; Cappelen: Oslo.

- H Sandvik. Fødselsomsorgen i Ytre Nordhordland 1858–87. En sammenlikning med nasjonal statistikk. Obstetrics in Peripheral Nordhordland 1858–87. A Comparison with National Statistics Tidsskr Nor Lægeforen. 113(30): 1993; 3715–3717.

- OG Moseng. Ansvaret for undersåttenes helse 1603–850. Responsibility for the Health of Subordinates. 2003; Universitetsforlaget: Oslo.

- S Vangen, P Bergsjø. Dør kvinner av graviditet i dag?. Do women die from pregnancy today? Tidsskr Nor Lægeforen. 123(24): 2003; 3544–3545.

- P Børdahl, F Jerve Børdahl. Lovregulert kirurgi. Svangerskapsavbrudd og sterilisering. Law regulated surgery. Pregnancy termination and sterilisation. P, MH Moen, F Jerve. Midt i livet. Norsk gynekologisk forening 1946–1996. At Mid-Life. Norwegian Gynaecological Association 1946–1996. 1996; Tapir: Trondheim.

- I Blom, K Elvbakken. Linjer i abortlovgivning og abortpolitikk. Outline of abortion legislation and abortion politics Tidsskift for velferdsforskning. 4(1): 2001; 30–40.

- D Stenvoll. Abort og politikk. Abortion and politics. 1998; Alma Mater: Bergen.

- T Mohr. Katti Anker Møller – en banebryter. Katti Anker Møller – a pioneer. 1968; Tiden norsk forlag: Oslo.

- B Grünfeld. Legal abort i Norge. Legal abortion in Norway. 1973; Universitetsforlaget: Oslo.

- T Nordby. Karl Evang. En biografi. Karl Evang. A biography. 1989; Aschehoug: Oslo.

- Å Vigran, T Lappegård. 25 år med selvbestemt abort i Norge. 25 years of abortion on demand in Norway. At: ⟨http://www.ssb.no/vis/samfunnsspeilet/utg/200303/07/art-2003-06-20-01.html. ⟩.

- A Schøtz. Folkets helse – landets styrke 1850–2003. The people's health – the country's strength 1850–2003. 2003; Universitetsforlaget: Oslo.

- Act of 5 December 2003 No. 100 relating to the application of biotechnology in human medicine, etc. At: ⟨http://www.ub.uio.no/cgi-bin/ujur/ulov/sok.cgi. ⟩.

- LM Reinar, A Hægeland, MF Tollefsen. HIV screening during pregnancy in Norway. Tidsskr Nor Lægeforen. 120(2): 2000; 221–224.

- E Aanesen. Ikke send meg til en “kone”, doktor. Fra 3 års fengsel til selvbestemt abort. Please don't send me to a quack, doctor. From 3 years imprisonment to abortion on demand. 1981; Oktober: Oslo.

- O Lian. Når helse blir en vare. Medikalisering og markedsorientiering i helsetjenesten. When health becomes a commodity. Medicalisation and market orientation in health care. 2003; Høyskoleforlaget: Kristiansand.

- Alle enige – ingenting gjort. Everybody agrees – nothing is done Dagens medisin. 25 March. 2004

- St. meld. nr. 14 (2001–2002) Evaluering av lov om medisinsk bruk av bioteknologi. White Paper: Evaluation of the Act relating to the application of biotechnology in medicine. 2002; Ministry of Health: Oslo.

- Ot.prp.nr.64 (2002–2003) Om lov om medisinsk bruk av bioteknologi m.m. (bioteknologiloven). Proposition to the Odelsting No. 64 (2002–2003) On the Act relating to the application of biotechnology in medicine (Biotechnology Act). 2003; Ministry of Health: Oslo.

- J Simensen. Norsk utviklingshjelps historie 1. 1952–1975: Norge møter den tredje verden. The history of Norwegian development assistance 1. 1952–1975: Norway meets the Third World. 2003; Fagbokforlaget: Bergen.

- N. Strøm. Fra familieplanlegging til reproduktiv helse. En studie av norsk bistand til befolkning og helse i utviklingsland fra 1968 til 1994 [From family planning to reproductive health. A study on Norwegian development assistance 1968–1994]. Master of Sociology thesis, Institute of Sociology and Social Geography. University of Oslo. 1998.

- AM Jensen Austveg. Fattigdom og befolkningsvekst: Om barnedødelighet og familieplanlegging. Poverty and population increase. On child mortality and family planning. B, J Sundby. Befolkningspolitikk mot år 2000. Population policies towards 2000. 1995; TANO: Oslo.

- Royal Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Norway. National Report on Population: Norway. Norwegian Background Paper No.2 for the International Conference on Population and Development 1994. Oslo, 1994.

- JS Singh. Creating a New Consensus on Population. 1998; Earthscan Publications: London.

- M Berggrav Austveg. Bilateral befolkningsbistand. Bilateral population assistance. B, J Sundby. Befolkningspolitik mot år 2000. Population policies towards 2000. 1995; TANO: Oslo.

- S Møgedal, A Miranda. The All India Hospitals Post Partum Programme (Sub District level). Report of a GOI/NORAD Review Mission, February–March 1990. 1990; Centre for Partnership in Development, Oslo/Christian Michelsen Institute: Bergen.

- Population Action International: Paying Their Fair Share? Donor Countries and International Population Assistance. Norway. At: ⟨http://www.populationaction.org/resources/publications/fair_share/dac98/norway.htm. ⟩.

- Funding Commitments to UNFPA: Report on contributions by member states to regular and other resources for 2004 and the future years. Report of the Executive Director. Executive Board of the United Nations Development Programme and the United Nations Population Fund. 5 May. 2004.

- IPPF Financial Statements 2003. Annual Report to the Governing Council for the year ending. 31 December. 2003.

- UNDP/UNFPA/WHO/World Bank Special Programme of Research, Development and Research Training in Human Reproduction (HRP): Financial matters. HRP Financial Report 2002–2003. Policy and Coordination Committee 17th Meeting. 30 June–1 July. 2004.

- Norad – Kanaler for norsk bistand innen helseområdet. Oppdatert desember 2004. Channels for Norwegian development assistance in the area of health. Updated December 2004. At: ⟨http://www.norad.no/default.asp?V_ITEM_ID=2985. ⟩.

- Bistanden øker med 1,6 milliarder kroner. Pressemelding, Utenriksdepartementet. Nr: 120/04. 06.10.2004 [Development assistance increases by 1.6 billion Norwegian Kroner. Press Release, Ministry of Foreign Affairs No. 120/04. 6 October. 2004].

- UD – Grunnlag og profil for intensivert norsk innsats i kampen mot hiv/aids. MFA - Basis and profile in intensified Norwegian efforts in combating HIV/AIDS. At: ⟨http://odin.dep.no/ud/norsk/dok/andre_dok/veiledninger/032001-120005/dok-bu.html. ⟩.

- SH Steen, IT Olsen, JE Kolberg. Review of Norwegian Health-Related Co-operation 1988–1997. 1999; Centre for Partnership in Development: Oslo.

- St. meld. Nr.35 (2003–2004) Felles kamp mot fattigdom. En helhetlig utviklingspolitikk. White Paper No.35 (2003–2004). United fight against poverty. A holistic development policy. 2004; Ministry of Foreign Affairs: Oslo.

- A Miranda. Utredning om norsk bistand til det indiske familieplanleggingsprogrammet. Report on Norwegian development assistance to the Indian family planning programme. 1993; Christian Michelsen Institute, DERAP: Bergen.

- G Geisler, B Austveg, T Bleie. Sida's work related to sexual and reproductive health and rights 1994–2003. Sida Evaluation 04/14. 2004; Sida: Stockholm.