Abstract

Despite important advances in expanding access to antiretroviral therapy in the countries most heavily affected by HIV/AIDS, there has been little consideration of the connections between HIV prevention, care and treatment programmes and reproductive health services. In this paper, we explore the integration of reproductive health services into HIV care and treatment programmes. We review the design and progress of the MTCT-Plus Initiative, which provides HIV care and treatment services to HIV positive women as well as their HIV positive children and partners. By emphasising the long-term follow-up of families and the provision of comprehensive care across the spectrum of HIV disease, MTCT-Plus highlights the potential synergies in linking reproductive health services to HIV care and treatment programmes. While HIV care and treatment programmes in resource-limited settings may not be able to integrate all reproductive health services into a single service delivery model, there is a clear need to include basic reproductive health services, such as access to appropriate contraception and counselling and management of unplanned pregnancies. The integration of these services would be facilitated by greater insight into the reproductive choices of HIV positive women and men, and into how health care providers influence access to reproductive health services of people with HIV and AIDS.

Résumé

Malgré une amélioration de l'accès à la thérapie antirétrovirale dans les pays les plus touchés par le VIH/SIDA, les liens entre les programmes de prévention, soins et traitement du VIH et les services de santé génésique n'ont guère été étudiés. Dans cet article, nous examinons l'intégration des services de santé génésique dans les programmes de soins et traitement du VIH. Nous analysons la conception et les progrès de l'Initiative PTME-Plus, qui assure des services de soins et traitement aux femmes séropositives ainsi qu'à leurs enfants et partenaires infectés. En privilégiant le suivi familial à long terme et les soins complets à tous les stades de l'infection, PTME-Plus souligne les synergies déclenchées en liant les services de santé génésique avec les programmes de soins et traitement du VIH. Si dans les environnements à ressources limitées, ces programmes ne peuvent pas toujours intégrer tous les services de santé génésique en un modèle unique de services, il faut néanmoins y inclure des services de santé génésique de base, comme l'accès à une contraception adaptée et des consultations, et la gestion des grossesses non désirées. L'intégration de ces services serait facilitée par une meilleure connaissance des choix génésiques offerts aux femmes et aux hommes séropositifs, et de l'influence des prestataires de soins de santé sur l'accès des séropositifs aux services de santé génésique.

Resumen

Pese a los importantes avances en la ampliación del acceso a la terapia antirretroviral en los países más afectados por el VIH/SIDA, no se ha pensado mucho en las conexiones entre los programas de prevención, atención y tratamiento del VIH, y los servicios de salud reproductiva. En este artículo, exploramos la integración de estos ãltimos a los programas de atención y tratamiento del VIH. Revisamos el diseño y los avances de la Iniciativa MTCT-Plus, que proporciona servicios de atención y tratamiento del VIH a las mujeres VIH-positivas, sus hijos y sus parejas VIH-positivos. Al dar énfasis al seguimiento de las familias a largo plazo y a la provisión de atención integral en todo el espectro de la enfermedad del VIH, la MTCT-Plus destaca las posibles sinergias en vincular los servicios de salud reproductiva a los programas de atención y tratamiento del VIH. Aunque es posible que, en ámbitos con pocos recursos, estos programas no logren integrar todos los servicios de salud reproductiva a un solo modelo de prestación de servicios, indudablemente es necesario incluir los servicios esenciales de salud reproductiva, como el acceso a anticonceptivos y consejería apropiada y el manejo de embarazos no planeados. La integración de estos servicios se facilitaría al tener más conocimiento sobre las decisiones reproductivas de las mujeres y los hombres VIH-positivos, y sobre cómo los profesionales de la salud influyen en el acceso de las personas con VIH/SIDA a los servicios de salud reproductiva.

The profound effects of HIV and AIDS on individuals and populations pose great challenges to reproductive health care services. With the increased burden of reproductive health conditions associated with HIV/AIDS, reproductive health programmes, and primary care services more generally, have been overwhelmed with the spread and maturation of the epidemic.Citation1Citation2 In this paper, we explore the integration of reproductive health services into HIV care and treatment programmes. We focus on the MTCT-Plus Initiative, a multinational programme that supports the expansion of HIV care and treatment in sub-Saharan Africa and southeast Asia, as a platform for a broader discussion of the potential synergy between reproductive health services and HIV treatment programmes.Citation3

The importance of reproductive health services for HIV positive women

In many instances, HIV positive women require special attention in reproductive health services. For example, as the incidence of cervical cancer increases dramatically with HIV infection,Citation4 services for the screening and treatment of cervical cancer are required.Citation5 Similarly, advanced HIV disease is associated with a substantial increase in several reproductive tract conditions, including vulvovaginal candidiasis and a range of sexually transmitted infections.Citation6Citation7 These conditions are a major source of morbidity among HIV positive women and may be more difficult to treat effectively than in HIV-negative women,Citation8 and more intensive protocols for diagnosis and treatment are required.Citation9Citation10 In addition, the impact of HIV on women's lives, including their roles as mothers, economic providers and caregivers within households,Citation11Citation12 emphasises the importance of psychosocial counselling and other interventions.Citation13Citation14 Although these and other services represent important components of care for HIV positive women, their availability is limited or even nonexistent in many of the countries heavily affected by HIV/AIDS.

Perhaps the most significant impact of HIV on women's reproductive health is on fertility and reproduction. HIV positive women and men continue to be sexually active after becoming aware of their infection,Citation15, Citation16, Citation17, Citation18, and the promotion of condoms and other forms of safe sex have received considerable attention in the prevention of secondary transmission of HIV.Citation19Citation20 However, HIV raises complex issues regarding childbearing and contraception.Citation21, Citation22, Citation23 There is conflicting evidence regarding the fertility desires of HIV positive women and men who know their status.Citation24, Citation25, Citation26, Citation27 And while most contraceptive methods have similar safety and effectiveness regardless of HIV infection,Citation28 use of hormonal contraceptives may increase the susceptibility of women or their partners to infection.Citation29Citation30 While evidence in this area is far from conclusive, it helps to underscore the far-reaching implications of the HIV/AIDS epidemic for women's reproductive health services.

The role of providers is critical in access to and quality of reproductive health services,Citation31, Citation32, Citation33 and their influence is likely to be magnified in delivering services to HIV positive women. Providers may have strong personal opinions regarding appropriate services for people with HIV.Citation34, Citation35, Citation36, Citation37 For example, if providers feel that people with HIV should not be sexually active, issues of contraception and reproduction may not be addressed adequately.Citation38 In other instances, specific services (e.g. sterilisation) may be promoted heavily to HIV positive women, with insufficient attention to women's own wishes.

The promise of HIV care and treatment

There have been remarkable advances in the availability of care and treatment for HIV positive individuals, including antiretroviral therapy (ART), in sub-Saharan Africa and other resource-poor settings with high HIV prevalence. From a handful of small pilot initiatives,Citation39, Citation40, Citation41 there has been significant progress towards large-scale primary care service delivery.Citation42 While many of these programmes are donor-funded, a number of national governments, including Botswana, Brazil, Thailand and South Africa, have incorporated ART into public sector health programmes.Citation43, Citation44, Citation45, Citation46

In settings where such services are delivered appropriately and effectively, HIV primary care programmes incorporating ART can have a significant positive impact on women's reproductive health. The occurrence of reproductive tract infections associated with HIV disease decreases with the initiation of ART.Citation47 Similarly the incidence of cervical cancer among women on ART is reduced (although not necessarily to levels observed among HIV-negative women),Citation48Citation49 and parallel reductions in maternal mortality are likely.Citation50 While the HIV epidemic continues to have an immense impact on people's lives, the availability of ART may help to reduce the social burden frequently associated with infection. In some settings, the availability of ART may help to transform the popular perception of HIV from a highly stigmatised, universally fatal condition to a chronic disease that can be managed effectively.Citation39, Citation51, Citation52, Citation53, Although ART does not represent a panacea for the far-reaching effects of HIV, much of the gendered discrimination and social and economic marginalisation associated with HIV may be at least partially alleviated.Citation52

Although there is potential for synergy between HIV treatment and reproductive health programmes, there has been little work to date on how they may be more closely linked. Guidelines for the delivery of HIV treatment services have paid minimal attention to the reproductive health needs of patients and the role of reproductive health services,Citation54Citation55 which may reflect the fact that HIV care and treatment programmes have been developed rapidly, with a strong emphasis on making essential services available as quickly as possible. The establishment of discrete programmes with few linkages may also reflect the vertical organisation of health care systems in many settings, as well as the different orientations and priorities of donors and programme personnel working in reproductive health and HIV/AIDS.Citation56, Citation57, Citation58 For example, health care workers in HIV care and treatment services usually come from a background of curative care services, while sexual and reproductive health services commonly represent a more preventative approach to health service delivery, making the integration of these two paradigms a challenge in many settings.

Integration and linkage of services

HIV primary care presents an important venue for direct delivery of or strong connections to reproductive health services for HIV positive women and men, a patient population that most reproductive health services may have difficulty in reaching. The most obvious advantage of this approach is the improved overall quality of health services delivered to patients. The reproductive health service needs of HIV positive women are likely to change over time, such as the caution against use of intrauterine devices among women with advanced HIV disease.Citation28 Similarly, changes in HIV treatment that affect reproductive health, such as an antiretroviral drug that may be teratogenic or interact with hormonal contraceptives, can be promptly and effectively linked to appropriate counselling on the use of a different method of contraception.Citation59

There is also a more subtle advantage to the integration of reproductive health services with HIV care and treatment. Unlike most other forms of primary health care in resource-limited settings, HIV care requires long-term continuity of care, in which the relationship between patients and health care services is critical in shaping health outcomes, e.g. by improving retention in care, early identification of symptoms and problems, or adherence to medication.Citation60 HIV care services that are able to address their patients' general health needs, including reproductive health needs, may be more likely to establish stronger patient–provider relationships with better patient outcomes.Citation61

In addition, HIV care and treatment services present an important opportunity for improving reproductive health. Longitudinal patient contact provides a unique chance to follow patients with ongoing reproductive health problems that are unlikely to be resolved during a single clinic visit. Moreover, programmes that emphasise enrolling HIV positive partners and families into the same services are able to engage women and men together, presenting valuable opportunities when both partners require treatment such as in STI management.

The MTCT-Plus Initiative

In many respects, the MTCT-Plus Initiative bridges the divide between reproductive health services and HIV care and treatment programmes. The Initiative was formed in 2001 as part of the international movement to expand access to HIV care and treatment in the countries hardest hit by HIV.Citation62Citation63 The concept of MTCT-Plus was shaped by the recognition that early programmes to prevent mother-to-child transmission (PMTCT) of HIV often provided minimal or no care to HIV positive mothers, missing an obvious opportunity to promote women's health and prolong their lives,Citation64, Citation65, Citation66 repeating similar shortcomings found in maternal and child health programmes.Citation67 To date, 13 programmes have been establishedFootnote* in Côte d'Ivoire (1), Cameroon (1), Kenya (2), Mozambique (1), Rwanda (1), South Africa (3), Thailand (1), Uganda (2) and Zambia (1), which are funded by a number of philanthropic foundations and other donors.

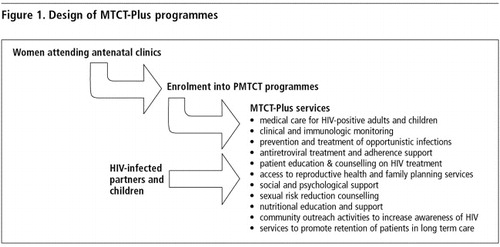

Sites supported by the MTCT-Plus Initiative are all service delivery organisations with a range of academic, non-governmental and public sector institutional affiliations. MTCT-Plus services are located in an HIV primary care setting to which women already identified as HIV positive from PMTCT services are referred during either the antenatal or post-natal period. At each site, MTCT-Plus services are delivered by a multidisciplinary team of nurses, doctors, counsellors and other personnel. Programmes share a common design, in which HIV positive women are enrolled into long-term HIV primary care. Once a woman is enrolled into MTCT-Plus, she may refer her partner, children and other HIV positive household members, who can then access a comprehensive package of long-term, family-focused care and treatment services. The model aims to provide integrated medical and psychosocial support services through a single programme, including clinical care (with antiretroviral treatment when indicated), nutrition, counselling and other supportive care. Access to reproductive health services is a key element in this approach, and all sites either provide contraception and other reproductive health services on-site, or through referrals (either at the same or neighbouring facilities). The specific elements included in the MTCT-Plus package of care are shown in . While existing PMTCT programmes are not directly addressed through MTCT-Plus services, MTCT-Plus encourages the early identification of HIV in pregnant women and their enrolment in MTCT-Plus services to allow the initiation of antiretroviral therapy where indicated. Rapid initiation of antiretroviral therapy in pregnant women can lead to improvements in maternal health and pregnancy outcomes in this high-risk group, as well as further decrease the vertical transmission of HIV.

Focus on women in PMTCT programmes and their HIV positive children

The MTCT-Plus Initiative emphasises two unique structural features. First, it focuses on women enrolled in PMTCT interventions and their HIV positive children as an entry point for family-based HIV primary care. This approach recognises the central role that women play as parents and heads of households.Citation3 Second, it emphasises comprehensive HIV primary care across the spectrum of HIV disease. While adults and children with advanced HIV-related illness receive ART, care and treatment is also provided to people who are healthy. All MTCT-Plus participants receive intensive adherence support, psychosocial services (e.g. counselling, education and access to peer support), preventive services (such as prophylaxis against opportunistic infections), nutritional counselling and support and access to reproductive health services.

In addition to helping to delay the progression of HIV disease,Citation68Citation69 care is family-focused and the same clinicians can provide care for family members at different stages of disease to establish long-term relationships with the health service. Such relationships make an important contribution to adherence to therapy and permit early identification of disease complications; they also provide an ideal setting for providing HIV positive women and men with other interventions, most notably around sexual and reproductive health.

Technical assistance and programmatic approaches

Sites are provided with technical assistance necessary to develop effective programmes rapidly. This includes intensive training for all staff, including non-medical staff. Topics for training include the relevant biomedical aspects of HIV care and treatment, such as the natural history of HIV disease, common illnesses and their treatment, and the use of antiretroviral drugs. However training also emphasises the key programmatic approaches to providing effective, comprehensive woman-focused, family-centred HIV care. In addition, sites are provided with support materials to assist providers (algorithms for patient management, flip cards for rapid access to commonly required information) as well as patients (such as pill boxes and other adherence support tools). The Initiative also provides structured medical records to help ensure that key aspects of clinical care, including counselling and referrals for reproductive health services, are delivered.

By enrolling HIV positive adults across the spectrum of HIV disease, MTCT-Plus programmes are able to provide reproductive health services in the years prior to the development of symptomatic illness. MTCT-Plus programmes emphasise access to contraception, counselling on condom use and secondary prevention of HIV, early diagnosis and treatment of sexually transmitted infections, access to cervical cancer screening and treatment where these are available, and access to safe abortion services where these are legal and available. In keeping with the overall vision of the MTCT-Plus Initiative, this package of care is unique in its integration of HIV treatment and ART with other primary care services not traditionally considered part of HIV care.

Because the MTCT-Plus Initiative works in countries with different health care systems, specific decisions regarding when and how various reproductive health services are delivered are taken by individual sites. All sites are encouraged to integrate these services directly, but where this is not feasible because of the structure of the local health care service, sites are encouraged to strengthen links within or between facilities to ensure efficient referrals to meet patients' needs.

There are two cross-cutting issues related to reproductive health that the Initiative addresses. First, the technical inputs provided by the Initiative help to reinforce the over-arching importance of the reproductive rights of HIV positive women and men. Although their primary mandate is not the delivery of reproductive health services, these HIV care and treatment programmes have a clear obligation to support reproductive health in the context of health and human rights. Second, there are instances in which HIV care and treatment services can directly influence reproductive health, as in the case of drug interactions, e.g. between antiretrovirals, drugs used to treat tuberculosis and hormonal contraceptives, or teratogenicity associated with one of the available antiretroviral agents.

The need for effective communication between providers of HIV care and treatment and reproductive health care is emphasised throughout the MTCT-Plus Initiative. Each MTCT-Plus site begins with a successful PMTCT programme, with antenatal care providers as integral members of the care team. MTCT-Plus clinical algorithms support continued attention to reproductive health, as participants are asked about contraceptive use and pregnancy status at each follow up visit. Technical assistance focuses on multidisciplinary care and communication, and specifically on the care of the HIV positive pregnant woman and the use of ART during pregnancy. To this end, the Columbia Clinical Manual used by MTCT-Plus sites includes chapters on family planning and reproductive health, care of the HIV positive pregnant woman, and family-focused, multidisciplinary care.Citation70

Programme participants and utilisation of reproductive health services

Data from standardised patient records allow the monitoring of enrollment into MTCT-Plus services and tracking of health care received by patients at each participating site. From early 2003 to late 2004, more than 6,000 people have been enrolled in the MTCT-Plus Initiative. Most are women identified through PMTCT services (52%) or their children (32%). 13% of participants are men, and 3% are other adult members of the index woman's household. An estimated 89% of adults have disclosed their HIV serostatus to at least one other person, the majority of these to their partner, and approximately one-quarter of women enrolled in the programme have chosen to enroll a male partner. Most of the enrolled adults to date (80%) are quite healthy, at WHO Stages I or II when they first enter the programme. The demand for reproductive health services in this population is reflected in women's use of condoms and other contraceptive methods reported during their first visit to MTCT-Plus services. At enrollment, 44% of women who were not pregnant reported using non-barrier contraceptives (primarily hormonal methods or sterilisation), while 30% reported using condoms (8% of women reported dual method use). However, one-third of women reported no method use, and a number of new pregnancies were observed among women enrolled (pregnancy incidence, 2.9/100 person-years), most among women not using any method.Citation71 However, women were not asked whether these were intended pregnancies or represented an unmet need for contraception.

Discussion

The MTCT-Plus Initiative has shown the value of linking HIV care and treatment and reproductive health services. How can these best be brought together? Delivering certain aspects of reproductive health care within HIV care and treatment services is the most straightforward approach, and is feasible in programmes delivering comprehensive HIV primary care to individuals across the spectrum of HIV-related illness. However, in situations where HIV programmes are focused solely on the provision of antiretroviral therapy, reproductive health care services are likely to be accessible only by referral to separate services.

There are several potential challenges to providing reproductive health services in the context of HIV primary care. For HIV treatment programmes, reproductive health care may be viewed by donors or programme managers as a distraction from delivering much-needed antiretroviral therapy. Health care providers in HIV programmes may require supplemental training in order to provide appropriate care, and may view these additional responsibilities as an unnecessary burden. While such barriers require attention, they are by no means insurmountable.

A further question is which reproductive health care services should be offered on-site by HIV treatment programmes, and which should be provided through referral to reproductive care services? While the answer will vary across countries and health systems, we propose a simple framework for thinking about how services may be linked. First, at a minimum, all HIV care and treatment programmes should provide on-site the most frequently required reproductive health services that can be delivered with little additional training. In most settings, this will include a range of contraceptives along with male and female condoms, screening and treatment for sexually transmitted infections, and appropriate counselling and support around reproductive choice, violence against women and sexual risk reduction.

A second tier of reproductive health services are less commonly required and need more specialised provider training, such as cervical cancer screening and treatment or abortion services (including post-abortion care). In most settings, these types of reproductive health services may be made available through referral to another clinic, either at the same facility or off-site.

Referrals to antenatal and obstetric care should also be utilised where these services are well-developed. While HIV care and treatment services have an important role in assisting antenatal and obstetric services in meeting the special needs of HIV positive women, it should be unnecessary to duplicate these services. However in settings where maternal and child health services are less developed, HIV care and treatment programmes may need to take responsibility for obstetric care of HIV positive pregnant women.

Regardless of the exact approach to the integration of these services, the establishment of effective communication between providers of reproductive health care and HIV care and treatment is critically important, whether services are delivered at the same site by different providers or at different locations. The transfer of relevant clinical and social information, as well as medical records, is also essential and should be a focus of advanced planning and problem-solving. Instituting effective communication between providers working in separate health services is an ongoing challenge.Citation72 While attempts have been made in the past to develop communication between providers working in these areas, we believe the emergence of ART services provides a valuable new opportunity to implement more effective communication. On one hand, because of their novelty, HIV care and treatment services incorporating ART are likely to receive special consideration and interest from many reproductive health service providers (as well as individuals working in other services which may be involved in referral networks). On the other hand, in our experience providers working in HIV care and treatment quickly come to recognise the critical role that other health services play in meeting the health needs of HIV positive patients receiving ongoing care. As a result, the availability of ART may see both HIV and reproductive health service providers having greater appreciation of, and paying increased attention to, the need for communication between them.

Looking ahead

While the importance of linking reproductive health services to HIV care and treatment programmes is clear, there are few models for integrated service delivery and little research to guide “best practices”. Given the increasing number of HIV care and treatment programmes in resource-poor settings, there is a valuable opportunity for more formal research focused on these questions.

For example, there are few insights into the reproductive choices and needs of HIV positive women and men in much of the developing world. Participatory research and advocacy around these issues, most notably by the Voices and Choices project of the International Community of Women Living with HIV/AIDS, has suggested that the fertility desires of HIV positive women are diverse, and may not be adequately addressed by existing, disparate reproductive health and HIV care and treatment services.Citation38Citation73 Despite these preliminary insights there is a clear need for further examination of these issues, particularly in the context of HIV care and treatment, in order to gain a better understanding of how services can be adapted to best meet women's needs. It is also unclear how different interventions for HIV positive women and men, most notably the availability and uptake of ART, may influence reproductive health needs and service delivery.Citation74 In addition, there are few insights from sub-Saharan Africa into how health care providers influence access to reproductive health services by HIV positive individuals. Evidence from Brazil suggests that in some settings providers may be reluctant to provide HIV positive women and men with the same reproductive choices afforded to HIV negative individuals.Citation26Citation35 In these instances, there may be particular scope for interventions that help to improve the quality of service provision and ensure reproductive rights are clearly supported.

The MTCT-Plus Initiative provides a model of comprehensive care, treatment and support that helps to address the reproductive health needs of HIV positive women. The goal of the Initiative is to demonstrate the value of this model of care, in the hope that different aspects of this approach may be applied to other health services for HIV positive individuals living in resource-limited settings. With greater understanding of the reproductive health care needs of HIV positive women and men, MTCT-Plus and other HIV care and treatment programmes can develop stronger links with reproductive health services to improve the quality of health care delivered to people living with HIV.

Acknowledgements

The MTCT-Plus Initiative is funded through grants from the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, William and Flora Hewlett Foundation, David and Lucile Packard Foundation, Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, Henry J Kaiser Family Foundation, John D and Catherine T MacArthur Foundation, Rockefeller Foundation and Starr Foundation. Additional support is provided by the United States Agency for International Development. We acknowledge members of the MTCT-Plus Secretariat at Columbia University Mailman School of Public Health for their contributions to this programme. We thank the staff working at MTCT-Plus programmes whose dedication has been critical in delivering comprehensive care to HIV positive women and their families.

Notes

* Participating MTCT-Plus programmes are: Mbingo and Banso Hospitals, Bamenda, Cameroon; Formation Sanitaire Urbaine de Yopougon-Attié, Abidjan, Côte d'Ivoire; Nyanza Provincial General Hospital, Kisumu, Kenya; Moi Hospital/Mosoriot Rural Health Centre, Eldoret, Kenya; Day Hospitals in Beira and Chimoio, Mozambique; Treatment and Research AIDS Centre/Kigali Health Centres, Kigali, Rwanda; Perinatal HIV Research Unit, Chris Hani Baragwanath Hospital, Soweto, South Africa; Langa Clinic, City of Cape Town Health Department, Cape Town, South Africa; Ekuphileni Clinic/Cato Manor, University of KwaZulu-Natal, Durban, South Africa; Thai Red Cross AIDS Research Centre, Bangkok, Thailand; Mulago Hospital, Kampala, Uganda; St. Francis Nsambya Hospital, Kampala, Uganda; Chelstone District Health Clinics, Lusaka, Zambia.

References

- A Buve, S Kalibala, J McIntyre. Stronger health systems for more effective HIV/AIDS prevention and care. International Journal of Health Planning Management. 18(Suppl 1): 2003; S41–S51.

- SR Benatar. Health care reform and the crisis of HIV and AIDS in South Africa. New England Journal of Medicine. 351(1): 2004; 81–92.

- M Rabkin, WM El-Sadr. Saving mothers, saving families: The MTCT-Plus Initiative. WHO Perspectives and practice in antiretroviral treatment. 2003; World Health Organization: Geneva.

- PK Drain, KK Holmes, JP Hughes. Determinants of cervical cancer rates in developing countries. International Journal of Cancer. 100(2): 2002; 199–205.

- HS Cronje. Screening for cervical cancer in developing countries. International Journal of Gynaecology & Obstetrics. 84(2): 2004; 101–108.

- JD Sobel. Vulvovaginal candidiasis: a comparison of HIV-positive and -negative women. International Journal of STD & AIDS. 13(6): 2002; 358–362.

- P Moodley, C Connolly, AW Sturm. Interrelationships among human immunodeficiency virus type 1 infection, bacterial vaginosis, trichomoniasis, and the presence of yeasts. Journal of Infectious Diseases. 185(1): 2002; 69–73.

- P Moodley, D Wilkinson, C Connolly. Influence of HIV-1 coinfection on effective management of abnormal vaginal discharge. Sexually Transmitted Diseases. 30(1): 2003; 1–5.

- AM Levine. Evaluation and management of HIV-infected women. Annals of Internal Medicine. 136(3): 2002; 228–242.

- HE Cejtin. Gynecologic issues in the HIV-infected woman. Obstetrics & Gynecology Clinics of North America. 30(4): 2003; 711–729.

- G Baingana, KH Choi, DC Barrett. Female partners of AIDS patients in Uganda: reported knowledge, perceptions and plans. AIDS. 9(Suppl.1): 1995; S15–S19.

- E Lindsey, M Hirschfeld, S Tlou. Home-based care in Botswana: experiences of older women and young girls. Health Care for Women International. 24(6): 2003; 486–501.

- AA Krabbendam, B Kuijper, IN Wolffers. The impact of counselling on HIV-infected women in Zimbabwe. AIDS Care. 10(Suppl.1): 1998; S25–S37.

- S Maman, J Mbwambo, NM Hogan. Women's barriers to HIV-1 testing and disclosure: challenges for HIV-1 voluntary counselling and testing. AIDS Care. 13(5): 2001; 595–603.

- S Allen, J Meinzen-Derr, M Kautzman. Sexual behavior of HIV discordant couples after HIV counseling and testing. AIDS. 17(5): 2003; 733–740.

- Y Nebie, N Meda, V Leroy. Sexual and reproductive life of women informed of their HIV seropositivity: a prospective cohort study in Burkina Faso. Journal of the Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome. 28(4): 2001; 367–372.

- RW Ryder, VL Batter, M Nsuami. Fertility rates in 238 HIV-1-seropositive women in Zaire followed for 3 years post-partum. AIDS. 5(12): 1991; 1521–1527.

- RW Ryder, C Kamenga, M Jingu. Pregnancy and HIV-1 incidence in 178 married couples with discordant HIV-1 serostatus: additional experience at an HIV-1 counselling centre in the Democratic Republic of the Congo. Tropical Medicine & International Health. 5(7): 2000; 482–487.

- TE Wilson, ME Gore, R Greenblatt. Changes in sexual behavior among HIV-infected women after initiation of HAART. American Journal of Public Health. 94(7): 2004; 1141–1146.

- JD Auerbach. Principles of positive prevention. Journal of the Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome. 37(Suppl.2): 2004; S122–S125.

- W Cates Jr. Contraceptive choice, sexually transmitted diseases, HIV infection, and future fecundity. Journal of the British Fertility Society. 1(1): 1996; 18–22.

- CD Williams, JJ Finnerty, YG Newberry. Reproduction in couples who are affected by human immunodeficiency virus: medical, ethical, and legal considerations. American Journal of Obstetrics & Gynecology. 189(2): 2003; 333–341.

- HS Mitchell, E Stephens. Contraceptive choice for HIV positive women. Sexually Transmitted Infections. 80(3): 2004; 167–173.

- JL Chen, , KA Philips, , DE Kanouse, . Fertility desires and intentions of HIV-positive men and women. Family Planning Perspectives. 2001; 33(4): 144–52,165.

- AK Smits, CA Goergen, JA Delaney. Contraceptive use and pregnancy decision making among women with HIV. AIDS Patient Care & STDS. 13(12): 1999; 739–746.

- V Paiva, EV Filipe, N Santos. The right to love: the desire for parenthood among men living with HIV. Reproductive Health Matters. 11(22): 2003; 91–100.

- V Paiva, MR Latorre, N Gravator. Sexuality of women living with HIV in Sao Paulo. Cadernos de Saude Publica. 18: 2002; 109–118.

- World Health Organization. Medical Eligibility for Contraceptive Use. 3rd ed, 2004; WHO: Geneva.

- H Martin, P Nyange, B Richardson. Hormonal contraception, sexually transmitted diseases, and risk of heterosexual transmission of human immunodeficiency virus type 1. Journal of Infectious Diseases. 178: 1998; 1053–1059.

- L Lavreys, JM Baeten, HL Martin. Hormonal contraception and risk of HIV-1 acquisition: results of a 10-year prospective study. AIDS. 18(4): 2004; 695–697.

- JN Isaacs, MD Creinin. Miscommunication between healthcare providers and patients may result in unplanned pregnancies. Contraception. 68(5): 2003; 373–376.

- S Rama Rao, M Lacuesta, M Costello. The link between quality of care and contraceptive use. International Family Planning Perspectives. 29(2): 2003; 76–83.

- V Sychareun. Meeting the contraceptive needs of unmarried young people: attitudes of formal and informal sector providers in Vientiane Municipality, Lao PDR. Reproductive Health Matters. 12(23): 2004; 155–165.

- TG Heckman, AM Somlai, J Peters. Barriers to care among persons living with HIV/AIDS in urban and rural areas. AIDS Care. 10(3): 1998; 365–375.

- DR Knauth, RM Barbosa, K Hopkins. Between personal wishes and medical "prescription": mode of delivery and post-partum sterilisation among women with HIV in Brazil. Reproductive Health Matters. 11(22): 2003; 113–121.

- BH Chi, K Chansa, MO Gardner. Perceptions toward HIV, HIV screening, and the use of antiretroviral medications: a survey of maternity-based health care providers in Zambia. International Journal of STD & AIDS. 15(10): 2004; 685–690.

- RL Carr, LF Gramling. Stigma: a health barrier for women with HIV/AIDS. Journal of the Association of Nurses in AIDS Care. 15(5): 2004; 30–39.

- R Feldman, C Maposhere. Safer sex and reproductive choice: findings from “positive women: voices and choices” in Zimbabwe. Reproductive Health Matters. 11(22): 2003; 162–173.

- P Farmer, F Leandre, JS Mukherjee. Community-based approaches to HIV treatment in resource-poor settings. Lancet. 358(9279): 2001; 404–409.

- S Phiri, R Weigel, M Housseinipour. The Lighthouse: A centre for comprehensive HIV/AIDS treatment and care in Malawi. WHO Perspectives and practice in antiretroviral treatment. 2004; World Health Organization: Geneva.

- LG Bekker, C Orrell, L Reader. Antiretroviral therapy in a community clinic–early lessons from a pilot project. South African Medical Journal. 93(6): 2003; 458–462.

- World Health Organization. Treating 3 million by 2005: making it happen. The WHO and UNAIDS global initiative to provide antiretroviral therapy to 3 million people with HIV/AIDS in developing countries by the end of 2005. 2003; WHO: Geneva.

- P Phanuphak. Antiretroviral treatment in resource-poor settings: what can we learn from the existing programmes in Thailand?. AIDS. 18(Suppl.3): 2004; S33–S38.

- SS Abdool Karim, Q Abdool Karim, C Baxter. Antiretroviral therapy: challenges and options in South Africa. Lancet. 362(9394): 2003; 1499.

- E Susman. Botswana gears up to treat HIV patients in Africa's largest program. AIDS. 23(18): 2004; 2.

- PR Teixeira, MA Vitoria, J Barcarolo. Antiretroviral treatment in resource-poor settings: the Brazilian experience. AIDS. 18(Suppl.3): 2004; S5–S7.

- FJ Palella, KM Delaney, AC Moorman. Declining morbidity and mortality among patients with advanced human immunodeficiency virus infection. HIV Outpatient Study Investigators. New England Journal of Medicine. 338(13): 1998; 853–860.

- I Heard, V Schmitz, D Costagliola. Early regression of cervical lesions in HIV-seropositive women receiving highly active antiretroviral therapy. AIDS. 12(12): 1998; 1459–1464.

- WR Robinson, D Freeman. Improved outcome of cervical neoplasia in HIV-infected women in the era of highly active antiretroviral therapy. AIDS Patient Care & STDS. 16(2): 2002; 61–65.

- A Rosenfield, K Yanda. AIDS treatment and maternal mortality in resource-poor countries. Journal of the American Medical Womens Association. 57(3): 2002; 167–168.

- AE Bos, G Kok, AJ Dijker. Public reactions to people with HIV/AIDS in The Netherlands. AIDS Education & Prevention. 13(3): 2001; 219–228.

- A Berkman. Confronting global AIDS: prevention and treatment. American Journal of Public Health. 91(9): 2001; 1348–1349.

- A Castro, P Farmer. Understanding and addressing AIDS-related stigma: from anthropological theory to clinical practice in Haiti. American Journal of Public Health. 95(1): 2005; 53–59.

- Partners in Health. The PIH guide to the community-based treatment of HIV in resource-poor settings. Bangkok Edition. 2004; Partners in Health: Boston.

- World Health Organization. Scaling up antiretroviral therapy in resource-limited settings: Treatment guidelines for a public health approach, 2003 revision. 2003; WHO: Geneva.

- I Askew, M Berer. The contribution of sexual and reproductive health services to the fight against HIV/AIDS: a review. Reproductive Health Matters. 11(22): 2003; 51–73.

- L Lush, J Cleland, G Walt. Integrating reproductive health: myth and ideology. Bulletin of World Health Organization. 77(9): 1999; 771–777.

- M Oliff, P Mayaud, R Brugha. Integrating reproductive health services in a reforming health sector: the case of Tanzania. Reproductive Health Matters. 11(21): 2003; 37–48.

- JD Shelton, EA Peterson. The imperative for family planning in ART therapy in Africa. Lancet. 364(9449): 2004; 1916–1918.

- E Sabate. Adherence to Long-term Therapies: Evidence for Action. 2003; World Health Organization: Geneva.

- L Myer, W El-Sadr. Expanding access to antiretroviral therapy through the public sector: the challenge of retaining patients in long-term primary care. South African Medical Journal. 94(4): 2004; 273–274.

- M Mitka. MTCT-Plus program has two goals: end maternal HIV transmission + treat mothers. JAMA. 288(2): 2002; 153–154.

- SM Hammer, T Türmen, B Vareldzis. Antiretroviral guidelines for resource-limited settings: the WHO's public health approach. Nature Medicine. 8(7): 2002; 649–650.

- M Berer. Reducing perinatal HIV transmission in developing countries through antenatal and delivery care, and breastfeeding: supporting infant survival by supporting women's survival. Bulletin of World Health Organization. 77(11): 1999; 871–877.

- A Rosenfield, E Figdor. Where is the M in MTCT? The broader issues in mother-to-child transmission of HIV. American Journal of Public Health. 91(5): 2001; 703–704.

- F Perez, J Orne-Gliemann, T Mukotekwa. Prevention of mother to child transmission of HIV: evaluation of a pilot programme in a district hospital in rural Zimbabwe. BMJ. 329(7475): 2004; 1147–1150.

- A Rosenfield, D Maine. Maternal mortality–a neglected tragedy. Where is the M in MCH?. Lancet. 2(8446): 1985; 83–85.

- WW Fawzi, GI Msamanga, D Spiegelman. A randomized trial of multivitamin supplements and HIV disease progression and mortality. New England Journal of Medicine. 351(1): 2004; 23–32.

- SZ Wiktor, M Sassan-Morokro, AD Grant. Efficacy of trimethoprim-sulphamethoxazole prophylaxis to decrease morbidity and mortality in HIV-1-infected patients with tuberculosis in Abidjan, Côte d'Ivoire: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 353(9163): 1999; 1469–1475.

- M Rabkin, W El-Sadr, EJ Abrams. The Columbia Clinical Manual. 2004; International Center for AIDS Programs, Mailman School of Public Health, Columbia University: New York.

- L Myer, A Thompson, M Rabkin, . The impact of antiretroviral therapy on condom and contraceptive use among women enrolled in HIV primary care in resource-limited settings [MoOrD1089]. Paper presented at the XV International AIDS Conference. Bangkok: 2004.

- L Lush, G Walt, J Cleland. The role of MCH and family planning services in HIV/STD control: is integration the answer?. African Journal of Reproductive Health. 5(3): 2001; 29–46.

- B Yoddumnern-Attig, U Kanungsukkasem, S Pluemcharoen. HIV-positive women in Thailand: their voices and choices. 2003; International Community of Women Living with HIV/AIDS, Institute for Population and Social Research, Mahidol University, Faculty of Nursing, Khon Kaen University & Power of Life Support Group: United Kingdom & Thailand.

- L Myer, C Morroni, J Nachega. HIV-infected women in ART programmes. Lancet. 365(9460): 2005; 655–656.