In 1994, governments gave themselves 20 years to implement the ICPD Programme of Action. It was a wise decision. Anything less would have been far too short to achieve the goals espoused. Anything more would have risked it being forgotten, overtaken not only by new issues but also by the inevitable changes in government and politics over the years and all that that entails. It has certainly proven wise to review progress every five years. ICPD+5 re-energised the key players to set concrete targets, while the steadfastness of support for the Cairo goals by almost all countries in the past few years around ICPD+10 seems to be stronger and less ambiguous than it was in 1994. Many people around the world have been encouraged to take stock of what has been achieved, and the conclusion can only be that an incredible amount of change, mostly for the better, has taken place. This is the second issue of RHM with papers that reflect on what has been happening at country level since 1994, and although the journal will move on to other themes after this issue, authors are encouraged to continue submitting such papers, which are a valuable record of progress for our field.

This journal issue offers an unusual mix of papers. An important achievement from an international point of view is the World Health Organization's Strategy to Accelerate Progress towards the Attainment of International Development Goals and Targets Related to Reproductive Health, passed by the World Health Assembly in May 2004 by a large majority, part of which is reproduced in these pages. Now the many Ministers of Health who approved it need to make sure their countries implement its recommended actions before 2015. Then, as the first phase of the Millennium Project came to a close, in March 2005 the UN Secretary-General Kofi Annan in his report to the General Assembly mentioned the importance of sexual and reproductive health not once but twice, in what was probably his most important speech to date, in relation to achieving gender equality as part of the Millennium Development Goals (Haslegrave and Bernstein). In this sense, the ICPD Programme of Action can be seen as the foundation for the Millennium Development Goals, as described by the Swedish Association for Sexuality Education (RFSU) in four publications to celebrate the 10th anniversary of ICPD (Publications Round Up).

Leaders of the women's health movement from many countries in all regions have worked assiduously with policymakers to protect and promote the ICPD Programme of Action at UN and ECOSOC meetings of all kinds, and in all regions over the past decade. Real change, however, if it is to benefit the billions of women and men, girls and boys, alive and growing up today, can only take place and be sustained at national level. In this journal issue, there are reviews of national policy and programme developments in Brazil (Corrêa et al), Norway (Austveg and Sundby), Argentina (Petracci et al) and the UK (Davey). The papers from Brazil and Argentina show that these middle-income countries have moved forward at policy-making level, in starting to set up services and in fostering public awareness at grassroots level. The Norwegian paper is notable in that it compares the country's own sexual and reproductive health policy with its international development policy, identifying issues that have been treated as important inside Norway but have been peripheral to or ignored in their donor funding policies. There are also two papers on the Arab countries, one focusing on the current situation of young people in the region (DeJong et al) and the other on how increasing education and the changing economic situation of young women in the past two decades may pose a challenge to the patriarchal system (Fargues).

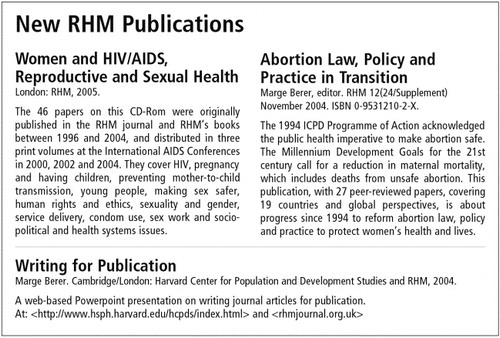

In addition to these country reviews, there are four theme-based papers. One is a review of progress in national abortion policies since 1994 (Hessini), which concludes that research and advocacy are helping to break the silence globally about unsafe abortion, that there is an emerging global movement supporting women's right to safe abortion, and that a great deal has been accomplished in the ten years since ICPD, in spite of serious setbacks in some countries and continuing obstacles. Indeed, the supplement to the November 2004 issue of RHM, entitled Abortion Law, Policy and Practice in Transition, which contains 27 papers on the current situation of abortion in all world regions, leads to a similar conclusion. The second paper looks at how women of many different backgrounds in Beirut, Lebanon, have come to understand and interpret the concept of reproductive health in the context of the harsh socio-economic conditions in which they live (Kaddour et al). The women in this study considered some of the most important factors for attaining reproductive health to be personal dignity, improved economic status, good marital relations and strength to cope with their lives, as well as health, responsibility and status issues attached to having children.

The third, a briefing paper for the Beijing+10 review, looks at the importance of gender equality for girls in education, as a prerequisite for all the health, social and development targets the world has set for itself, and calls for making primary education compulsory as well as free, school feeding programmes, prohibiting the worst forms of child labour and providing incentives to help compensate poor families for the loss of girls' labour when they are sent to school (Global Campaign for Education). Orphans and vulnerable children is the subject of the fourth paper (Lewis), which is a speech reflecting on the consequences of the failure of AIDS policy in the African continent in the past two decades to keep the mothers and fathers of young children alive to be able to bring them up. Finally, more than 20 years into the AIDS epidemic, more is being done about this, both for orphaned children and HIV positive mothers. This journal issue includes a paper describing the Columbia University PMTCT-Plus initiative (Myer et al), which provides HIV care and treatment services to HIV positive women as well as their positive children and partners, and emphasises the long-term follow-up of families and the provision of comprehensive care across the spectrum of HIV disease, including reproductive health care. Finally, a model exists that works and can be replicated. Now, there is no longer an excuse when prevention of mother-to-child transmission of HIV programmes fail to address the care and treatment needs of pregnant women and their families. A closely related paper in this issue, on maternal health and HIV (McIntyre), reminds us that women in developing countries are still 10–100 times more likely to die from pregnancy-related causes than women in the developed world today, and that an increasing number of those deaths are AIDS-related. Indeed, the risk of maternal death is so bad in the very poorest countries that in Sudan, for example, a girl is more likely to die in childbirth if she lives that long than to complete primary education (Research Round Up). That statistic is perhaps the most extreme measure of how far there is still to go in the poorest countries in implementing ICPD.

Thus, the picture in some countries is anything but rosy. First and most importantly, the poorest countries are being left behind. Second, the growth of rightwing political and religious dogma, often accompanied by an anti-science agenda and aggressive attempts to turn the clock back, not only on sexual and reproductive rights but on the autonomy of women and young people more broadly, represent a serious threat to health and human rights, especially for women. So far, the worst excesses of this reactionary trend are limited to a relatively small number of countries, and it is unlikely that the Roman Catholic church will now withdraw its considerable support for such activities. That leaves the threat posed by the United States as a major donor to this field and instigation by rightwing faith groups in the US of such reactionary activities in other countries.

The gap between rich and poor, and between those with power and those without, is widening across the globe. Moves to privatise the most basic services, from the water supply to health care to education, are shifting responsibility for public health and social welfare provision away from governments, with negative consequences for the poor that will not be reversible for decades to come. An example of the distortions of privatisation of health care is a paper in this journal issue on the excessive use of ultrasound screening in pregnancy in Syria by private doctors, who attend 80% of pregnant women, which seems to be done primarily to attract women to their clinics and increase their income (Bashour et al). Major gains, such as getting the price of AIDS medications reduced, which should have set an example for reducing all drug prices in future, and the successful campaign for the right of developing countries to be able to produce generic drugs, are being dealt heavy blows as “big pharma” fights back (HIV/AIDS Round Up). In short, there is a new kind of war on, and right now, social justice is in danger of losing.

With the HIV epidemic continuing to spread, work to address actual sexual behaviour realistically in order to make safer sex the social norm is being weighed down by demands for moral purity intertwined with the enticement of dollars. Yet countries and organisations who know full well that abstinence education on its own will only fuel the HIV epidemic, not stop it, seem unable to reject the moralism or the cash. unable to reject the moralism or the cash. The greatly increased attention now being paid to HIV treatment compared to ten years ago is both remarkable and long overdue. However, the family planning community has still not acknowledged that had they broadened their outreach to young people and those most vulnerable to HIV infection and been willing to promote condoms from the beginning, the face of the HIVepidemic might have been vastly different. It is time that they too begin to promote condom use widely, not only as a form of STI/HIV prevention but also for contraception, including to young people and to married couples, with the back-up of emergency contraception and safe abortion. It is telling that in the HIV prevention and treatment fields, there are campaigns for access to treatment, vaccine development and microbicide development but none devoted to promoting male and female condoms or indeed other forms of safer sex. To contribute to awareness of the importance of condoms for both contraception and STI/HIV prevention, RHM has added a new Round Up section on condoms to the journal. A roundtable conversation in this journal issue about where the feminist movement should be going reaches the conclusion that the greatest promise lies in the growing youth coalitions for sexual and reproductive health and rights and in the potential for opening up larger alliances around sexual and bodily rights with HIV/AIDS activists, sex workers, people living with HIV and AIDS and human rights organisations (Corrêa et al). One of the most important lessons on how to bring about change, however, is that unless a critical mass of support is achieved at grassroots level, progress is far more difficult to sustain. Hence, I would argue that the hardcore work of providing accurate information on sexual and reproductive health and rights and involving the public, especially young people, along with promoting progressive policies and good quality services, remains the overriding priority today.

There are many signs of progress, however. Issues such as female genital mutilation and violence against women were barely mentioned in most developing countries even ten years ago. Now they are very much in the public eye. Countries where abortion was so stigmatised that no one could even mention the word 20 years ago are debating the issue openly. A letter to the editor in this journal issue points out, however, that while some taboos are being challenged, the subject of sexual abuse of children remains shrouded in silence and more often than not, denied or excused and covered up.

Most ironic, perhaps, is that international priority placed on family planning services seems to have fallen to a lower level on the international agenda in the aftermath of Cairo, when support for the demographic imperative of reducing population growth was replaced by the ethical imperative to respect the right of women and couples to decide the number and spacing of their children. Yet the demand for family planning services continues to grow and must be met. From the point of view of women especially, family planning is as central to national (and personal) development as education and employment. Turning the practice of family planning into a social norm in almost all countries was one of the great achievements of the 20th century. In fact, the total fertility rate has fallen so quickly in the past decade that it is now below replacement level for half the world's population (Research Round Up). This success must be maintained, and research to find even more acceptable and easy-to-use methods, which provide not only protection against unwanted pregnancy but also sexually transmitted infection, must also be supported unstintingly.

Papers in this journal issue on family planning include one on the contemporary reasons behind long post-partum abstinence in Abidjan, Côte d'Ivoire, which is mainly used as a way to space births in a context of continuing low contraceptive use. However, the study finds that women are often torn between worries that their partner is “seeking elsewhere” if and might put them at risk of HIV if they resume sex too late, and the risk of early pregnancy if they resume sex too soon, a dilemma that family planning providers in this setting need to address (Desgrées-du-Loû et al). Another paper is on the practice of withdrawal in Turkey and what men have to say about it (Ortayli et al). The authors recommend more support for the practice of withdrawal, not only because it is free from side effects, easy to use and has no cost, but also because it is a way of increasing method choice and because male participation and responsibility in family planning are desirable. And, perhaps it is a way to reduce the risk of HIV transmission in the absence of condom use too.

One of the areas of reproductive health that RHM has been reluctant to take up is assisted conception, and although private clinics in developing countries for services such as in vitro fertilisation have mushroomed in the past decade, little is published about the use of these services by people in developing countries. Assisted conception has opened up a whole new area of reproductive law and policy as well as medical technology and service delivery. In the hope of encouraging more submissions on these topics, we are pleased to be able to reprint a paper on the widely differing legal and political restrictions on assisted conception services in European countries, and how these have led to “reproductive tourism”, that is, travelling to other countries for assisted conception services (Pennings). The paper is also a reflection on the rule of the majority over the minority in law and politics as in bioethics, and how democracy plays out in relation to individuals accepting or rejecting guidelines on what is permitted in assisted conception, e.g. whether sperm donation should be anonymous or not, who should be allowed to donate ova, or how many embryos should be replaced during in vitro fertilisation and which ones. The greater the restrictions, the more likely individuals are to seek services in other countries. This author argues convincingly against attempts to harmonise such guidelines and laws across Europe, since they will tend to be more rather than less restrictive and, in the absence of true consensus, are likely to please no one.

Finally, this journal issue contains a report of the AIDS 2004 conference In (Solomon), which describes the fact that the AIDS conference is really two conferences and calls for more meaningful partnerships and collaboration between the experts and those most vulnerable and affected by HIV so that there is progress to report by the time of the next conference in 2006. And there is a review of a new UN report, Women and HIV/AIDS: Confronting the Crisis, which questions why the report acknowledges that men are central to lowering heterosexual transmission rates yet suggests interventions in which men's role is treated merely as instrumental in reducing women's vulnerability rather than focusing on men's needs as well (Frasca).

In conclusion, there can be no doubt that countries are giving far more attention to all these issues compared even to ten years ago and working often beyond their capacity to create better policies and improve access to sexual and reproductive health information and services. An organised women's health advocacy movement working at national level is needed now more than ever to maintain national and international support for work on these issues, to take the lead in opposing anti-scientific and false about these issues claims and to expose and prevent undemocratic attempts to censor and undo work that has been formally approved, not once but many times, by almost all countries.