Abstract

Abortion was legalised in Nepal in September 2002 and manual vacuum aspiration is the main procedure used for safe abortion. Although medical abortion has not yet officially been introduced in Nepal, with the highly porous Indo-Nepal border and the easy availability of mifepristone and misoprostrol in Indian chemists' shops, it is possible the drugs are entering from Indian markets illegally. This study aimed to gauge current awareness of the availability of medical abortion drugs in Nepal and explore what health professionals and paramedics felt about the use of medical abortion to expand access to safe abortion in the country. Data were drawn from interviews with private obstetrician-gynaecologists, general physicians, paramedics, ayurvedic and homeopathic practitioners and chemists in 24 urban municipalities and peri-urban areas in Nepal. Various types of allopathic and indigenous forms of medicine for menstrual regulation in the Nepalese market were widely known whereas knowledge of the availability of mifepristone and misoprostrol was low. Almost all respondents had a positive view of the potential for providing mifepristone and misoprostol in Nepal and most thought that obstetrician-gynaecologists, general physicians and other certified abortion care providers should be able to provide the drugs. Many respondents were interested in doing so themselves. Registration of mifepristone and misoprostrol is the key to introducing medical abortion in Nepal and should happen as soon as possible.

Résumé

L'avortement a été légalisé au Népal en septembre 2002 et l'aspiration manuelle par le vide est la principale méthode utilisée. Bien que l'avortement médicamenteux n'ait pas encore été introduit officiellement dans le pays, compte tenu de la porosité de la frontière indo-népalaise et de la disponibilité de mifépristone et de misoprostol dans les pharmacies indiennes, il est possible que ces médicaments pénètrent illégalement de I'Inde. L'étude souhaitait déterminer si les professionnels médicaux et paramédicaux connaissaient la disponibilité de médicaments abortifs au Népal et recueillir leur opinion sur l'avortement médicamenteux pour élargir l'accès à l'avortement médicalisé dans le pays. Les données ont été tirées d'entretiens avec des obstétriciens-gynécologues privés, des médecins généralistes, du personnel paramédical, des praticiens ayurvédiques et homéopathiques et des pharmaciens dans 24 municipalités urbaines et périurbaines. Différentes formes allopathiques et autochtones de régulation menstruelle disponibles sur le marché népalais étaient largement connues, contrairement à la disponibilité de mifépristone et de misoprostol. Presque tous les répondants jugeaient positivement le potentiel de distribution de la mifépristone et du misoprostol au Népal et la plupart pensaient que les obstétriciens-gynécologues, les médecins généralistes et d'autres prestataires de soins d'avortement devraient pouvoir prescrire ces médicaments. Beaucoup de répondants souhaitaient le faire eux-mêmes. L'autorisation de mise sur le marché de la mifépristone et du misoprostol est essentielle pour introduire l'avortement médicamenteux au Népal et devrait se produire dès que possible.

Resumen

En Nepal, el aborto fue legalizado en septiembre de 2002, y la aspiración manual endouterina es el procedimiento de primera elección para el aborto seguro. Aunque el aborto con medicamentos aún no se ha lanzado oficialmente en Nepal, con la frontera Indo-Nepalesa tan abierta y la pronta disponibilidad de la mifepristona y el misoprostol en las tiendas de químicos indios, es posible que estos fármacos estén entrando de los mercados indios ilegalmente. Este estudio se propuso evaluar el conocimiento actual de la disponibilidad de los fármacos utilizados para inducir el aborto con medicamentos en Nepal y explorar las creencias de los profesionales de la salud y paramédicos respecto al uso del aborto con medicamentos para ampliar el acceso al aborto seguro en el país. Se recolectaron datos durante entrevistas con gineco-obstetras privados, médicos generales, paramédicos, practicantes de medicina ayurvédica y homeopática y químicos de 24 municipalidades urbanas y zonas peri-urbanas de Nepal. En el mercado nepalés se conocían diversos tipos de formas alopáticas e indígenas de medicinas para la regulación menstrual, pero no estaban muy enterados de la disponibilidad de la mifepristona y el misoprostol. Casi todos los participantes tenían un punto de vista positivo respecto al potencial de suministrar mifepristona y misoprostol en Nepal. La mayoría creía que los gineco-obstetras, médicos generales y otros prestadores certificados de servicios de aborto podrían suministrarlos. Muchos se interesaron por hacerlo ellos mismos. Para lograr el lanzamiento del aborto con medicamentos en Nepal, es imperativo registrar la mifepristona y el misoprostol lo antes posible.

Abortion was legalised in Nepal in September 2002 to improve the health status and condition of women. The new law allows abortion up to 12 weeks of pregnancy at the request of the woman, up to 18 weeks if the pregnancy results from rape or incest, and at any time during pregnancy on the advice of a medical practitioner, if the physical or mental health or life of the woman is at risk, or the fetus is impaired or has a condition incompatible with life.Citation1 Previous laws did not allow abortion under any circumstances and many women who had had an abortion were imprisoned.Citation2Citation3Citation4 Despite this, abortion was not uncommon in the country, and women with unintended pregnancies were compelled to seek unsafe and clandestine abortions, often risking their lives and health.

The 2001 Nepal Demographic and Health Survey found that more than one in five births was unwanted while 14% were mistimed,Citation5 and only 39% of currently married women were using modern contraception. Unintended pregnancies among young married women (15-24 years of age) were also high. The maternal mortality ratio is the highest in South Asia (539 per 100,000 live births) and according to a study conducted by the Ministry of Health in 1998, 54% of all hospital admissions were women with post-abortion complications.Citation6 Similarly a hospital-based study by the Center for Research on Environment Health and Population Activities (CREHPA) in 1999 found that 20-60% of women admitted as obstetric-gynaecological patients in the government hospitals were for abortion complications, mostly due to unsafe procedures. The nature of treatment required by these women included high doses of antibiotics, blood transfusions, intravenous fluids and sometimes laparatomy, and some required hospitalisation for over a week. Almost all the women (98%) attending these hospitals for treatment of abortion complications were married and from a poor economic background. Women who could afford to pay the high fees for a safe abortion went to private clinics in the major towns and cities or even to India for a termination.Citation7 Another study conducted among 61 private gynaecologists across the country revealed that the number of women requesting abortion in their clinics had been increasing over the years, especially in the terai (plain) belts.Citation8

Several studiesCitation9Citation10 have documented the use by Nepalese women of various herbal and harmful substances to abort unwanted pregnancies. Some of the common foods used have been white pumpkin (eaten raw or cooked), black sesame seeds, honey and green papaya. Non-edible, sometimes harmful substances have included the roots of various herbs, raw vermillion and glass powder. Prescription of ineffective Ayurvedic and other indigenous medicines by private medical practitioners, paramedics and chemists to women seeking terminations have also been reported.Citation10Citation11

Comprehensive abortion care services were introduced in Nepal in March 2004, roughly two years after abortion was legalised. These services incorporate pregnancy testing, pre-counselling (for the woman's informed decision about the pregnancy termination, about the abortion procedure, potential risks and consent), surgical abortion and post-counselling (about follow-up care, signs of complications, short ovulation time and need for family planning) and a supply of contraception of the woman's choice. Only institutions and individuals certified by the government are eligible to provide comprehensive abortion care services under the Safe Abortion Service Procedure.Citation12 As of August 2005, a total of 87 (53 government and 34 private and non-governmental) health institutions in the country have been approved by the government for providing comprehensive abortion care services. These 87 institutions are located in 49 out of 75 districts of the country.Citation13

Currently, His Majesty's Government Ministry of Health and Population is promoting manual vacuum aspiration (MVA) as the surgical procedure of choice for safe abortion in approved hospitals, other medical institutions and non-governmental organisations (NGOs). In addition, the introduction of appropriate new methods of abortion, including medical methods (depending upon the length of pregnancy, availability of services and trained providers), has been specified in the Safe Abortion Service Procedure.Citation12

Medical abortion using a combination of mifepristone followed by misoprostrol for pregnancy termination up to 63 days LMP has not yet been registered in Nepal. However, the highly porous Indo-Nepal border and the easy availability of mifepristone and misoprostrol from Indian chemistsFootnote* mean that the drugs may be being obtained illegally from Indian markets. In fact, misoprostol has always been available as an anti-ulcer drug in Nepal. Certain drugs manufactured in India and meant for treating “menstrual disorders” or regulating menstruation, including the banned drug EP Forte (popular and illegally prescribed for causing abortion by physicians in Nepal for years), are openly available from Nepalese chemists. Moreover, several mobile medicine dealers popularly known as Jholawala operate in the towns along the Indo-Nepalese border, smuggling in medicines from India at cheap rates and supplying them to Nepalese chemists.

Medical abortion has been shown to be acceptable in many countriesCitation14Citation15 and can be provided in settings where surgical abortion services may not be widely available and thus has the potential to increase access to safe abortion.Citation16 His Majesty's Government Ministry of Health and Population is considering the introduction of medical abortion technology in the country in the near future. Hence, an understanding of the situation on the ground and the feasibility of introducing mifepristone-misoprostol on a large scale is needed to help to design future training and service delivery programmes.

The study presented in this paper was aimed at understanding the current availability and use of medical abortion in Nepal and exploring what service providers felt about its use for expanding access to safe abortion in the country.

Participants and methodology

A total of 49 private obstetrician-gynaecologists, 55 general practitioners (GPs), 168 paramedics, 62 ayurvedic and homeopathic practitioners (AHPs) and 177 chemists were interviewed from 24 urban municipalities and peri-urban areas across the country. The study sites were purposively selected to cover all the terai towns and peri-urban areas along the Indo-Nepal border, the Kathmandu valley, the inner hills and inner terai areas. Executive members of relevant professional associations, i.e. the Nepal Medical Council, Nepal Medical Association, Nepal Society of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists and the National Chemists and Drug Association were also interviewed to obtain their perceptions of the potential use of medical abortion in the country.

Selection of obstetrician-gynaecologists and physicians was done randomly from the published lists of the Nepal Medical Council and the Pariwar Swastha Sewa Network, a private doctors' network. The lists of paramedics, ayurvedic and homeopathic practitioners and chemists in each town and peri-urban area were obtained from the respective district level associations and from the published lists of Sangini (Depo Provera) providers and outlets, who sell to private clinics and chemist shops since the method was approved in 1994. Sangini outlets are spread across all urban and peri-urban areas nationally. In one terai district (Rupendehi), the list of SEWA, a private network of nurses and paramedics, was also used to draw the sample of paramedics. In towns where published lists were not available, a list was drawn up by the study team by talking to key informants.

A structured questionnaire was used for the individual interviews, adapted from a questionnaire used by Ipas in a similar study in India.Citation17 The questionnaire consisted of open-ended and close-ended questions about the respondents' awareness about medical abortion and their attitude towards promoting it. The research team contacted some of the drug distributors, chemists, obstetrician-gynaecologists and paramedics in the Kathmandu valley and some of the border towns to obtain a list of the popular medicines prescribed by them for menstrual regulation and medical abortion, and interviewed them as well.

The study team was comprised of 10 field supervisors and 20 enumerators. The supervisors were responsible for identifying the different categories of respondents, supervising the interviews, conducting interviews with the doctors and exploring the network and supply chain of drugs in the towns. Interviews with the ayurvedic and homeopathic practitioners, paramedics and chemists were carried out by the enumerators. All completed questionnaires were coded and analysed using the SPSS programme.

Profile of the providers

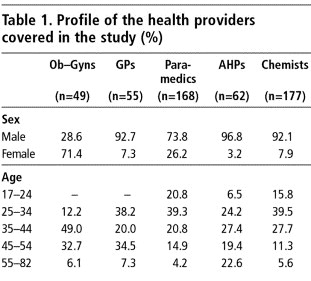

Male health care providers dominated in all categories of the study sample except the obstetrician-gynaecologists, of whom 71% were women. Female paramedics (auxiliary nurse-midwives and community medical assistants) comprised 26% of the 168 paramedics interviewed. In the remaining categories of health providers, less than 8% were women as such professions are generally held by men in Nepal. The age range of the respondents was broad, from as young as 17 (chemist) to as old as 82 years (ayurvedic practitioner), with most in the 25-54 age groups (Table 1).

Awareness of the availability of medicines for menstrual regulation

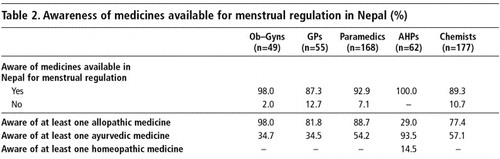

Nearly all the health care providers knew of at least one type of drug for menstrual regulation that was available (Table 2). Awareness of at least one type of allopathic drug was very high among the allopathic practitioners and chemists but low among the AHPs. However, almost all AHPs could name at least one type of ayurvedic drug for menstrual regulation, and only AHPs knew of any homeopathic medicines.

The respondents mentioned the names of 52 allopathic, 65 ayurvedic and 21 homeopathic medicines available for menstrual regulation. The most frequently mentioned allopathic drugs were oral contraceptive pills, iron tablets, Progesterone, EP Forte, Estrogen, Norethisterone, Clemenstol, Primanet N and Primotunt N. Combined oral contraceptive pills and iron tablets were the two most frequently mentioned pharmaceutical products considered to be effective for menstrual regulation, as were EP Forte and Estrogen tablets.

The 10 most frequently mentioned ayurvedic medicines prescribed for menstrual regulation were: Ashokarist, Mensure, Sundari Kalpa, Klot, Ergo tablets, Rajprawataniwati, Cremenaston, Rajonex, Nasta Pushpantak Ras and M2 Tone. Of these, Ashokarist, Mensure and Klot were the most commonly used for bringing on a period. The two most frequently mentioned homeopathic preparations were Pulsatilla and Pinus Lambertina. Other frequently cited homeopathic preparations were: Sabina, Caulophylum, Gossypium, Mensolex, Sepia, Ignitna, Thlaspi Bursa and Secale Cornutum. Most of these medicines are mainly used for bringing on a period and reducing abdominal pain during menstruation.

Awareness of the availability of medical abortion drugs

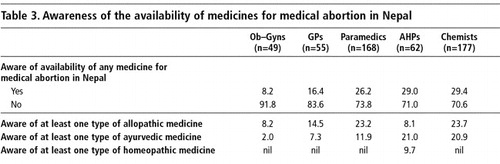

One question was asked about awareness of the availability of drugs for causing an abortion in Nepal and another about awareness of mifepristone and misoprostol. Awareness of the availability of drugs for abortion was low overall among all categories of respondents (Table 3). Respondents cited some of the same but fewer (31) allopathic medicines as they had mentioned previously for menstrual regulation. The most frequently cited, by over a half the respondents, was EP Forte. Oral contraceptive pills (12-14%) and Albendazole, which is a deworming medicine (7-12%), were also cited. No probing regarding mifepristone and misoprostrol was done at this stage, and the proportion of respondents citing the availability of misoprostol (2%) and mifepristone (2%) in the country was negligible.

The ayurvedic medicines for abortion mentioned were the same ones mentioned by providers for menstrual regulation, most commonly Mensure (34% of physicians and paramedics and 41% of chemists). Mensure is an unregistered ayurvedic capsule sold widely in the border towns by chemists for correcting irregular menses. According to the chemists who were selling this drug, three capsules per day of Mensure is usually prescribed to women seeking termination up to eight weeks of pregnancy. A chemist from Kakarbhitta, a border town, said that Mensure was quite effective during the first month after a missed period and that many women asked for these capsules. Klot was identified as an abortifacient by 18% of the physicians and paramedics, while Ergo tablets were mentioned by 24% of the chemists. Both these ayurvedic medicines are prescribed for bringing on a period. Rajprawantaniwati is another ayurvedic preparation from India (marketed in syrup form), which is believed by some health providers (18%) to have abortifacient properties if prescribed in higher doses than the prescribed limit for menstrual irregularity.

Among the homeopathic drugs prescribed for abortion, Mensolex (manufactured in Varanasi, India) is quite common. The package insert for Mensolex clearly states that the drug, which is in liquid form, should be used for purposes of regulating menses and for abortion. For abortion, a woman needs to consume 3 phials of the 15 ml liquid medicine in three days. According to a Kathmandu-based homeopathic doctor interviewed by the authors, Mensolex is 80% effective for pregnancy termination if the instructions are strictly followed.

Awareness of mifepristone and misoprostol

In India, mifepristone is sold under the brand names Mifegest, Mifeprin and Mtpill whereas misoprostol is sold under the brand names Cytotec, Cytolog, Zitotec, Misogon and Misoprost.Citation17

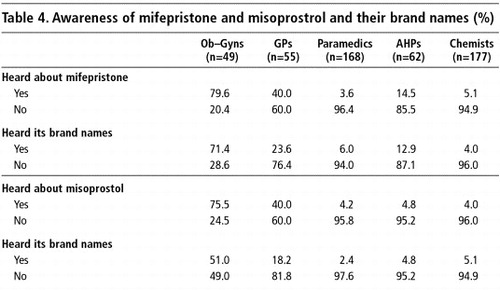

Following on from the earlier question about these two drugs, respondents were told about mifepristone and misoprostrol and the brand names under which these medicines are being sold in India, before they were asked if they were aware of them by name. There was a very high awareness of mifepristone and misoprostol among the obstetrician-gynaecologists (80%), but less among the GPs (40%) (Table 4). The proportion of paramedics and chemists who were aware of the drugs was very low by comparison. Awareness of their brand names followed a similar pattern.

The potential for providing medical abortion in Nepal

Two of the executive members of medical professional organisations who were interviewed were confident that there was potential for providing medical abortion in Nepal. Although they expressed caution about possible misuse of the drugs, they had positive views about medical abortion.

“Yes, very much [potential for providing medical abortion]…Since abortion is legalised… we can think of promoting medical abortion along with surgical abortion. The private sector is highly developed in Nepal. Once it is practised by the doctors and private sector, it will come into practice. Promoting medicines for inducing abortion certainly has potential in our country.” (General Secretary, Nepal Medical Association)

“Definitely [there is potential], but we should be careful while promoting medicines to induce abortion as these women might opt for medical abortion rather than family planning methods. As we have experience from India where women choose medical abortion rather than FP means.” (President, Nepal Society of Obstetricians & Gynaecologists)

Almost all the obstetrician-gynaecologists (92%), paramedics (96%) and chemists (94%) believed that there was potential for making mifeprostone and misoprostrol available in Nepal, and most of the general physicians (85%) and AHPs (68%) shared this view.

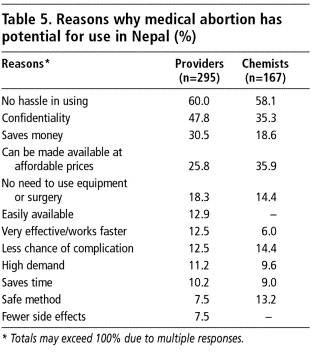

A long list of reasons why medical abortion has potential use in Nepal was given by the providers and chemists (Table 5). Their reasons were similar, with very few exceptions. More obstetrician-gynaecologists mentioned that there is no hassle in using medical abortion (62%) and that it does not require equipment or surgery (40%). A higher percentage of chemists (36%) than providers (26%) mentioned that medical abortion can be made available at affordable prices.

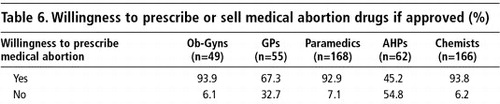

The few providers who did not have a positive view of the potential of medical abortion believed that it caused side effects and carried a risk of incomplete abortion. Some also felt that introduction of medical abortion in the country could lead to social corruption, i.e. pre-marital sex among young girls. Concerns about an increase in the abortion rate were also mentioned. Almost all the obstetrician-gynaecologists (94%) and paramedics (93%) expressed their willingness to prescribe or sell mifepristone-misoprostol for medical abortion in future, and most of the GPs (67%). Fewer AHPs (45%) were willing. Similarly, nearly all the chemists (94%) expressed their willingness to stock these medicines in their shops (Table 6).

Types of providers who should be allowed to provide medical abortion

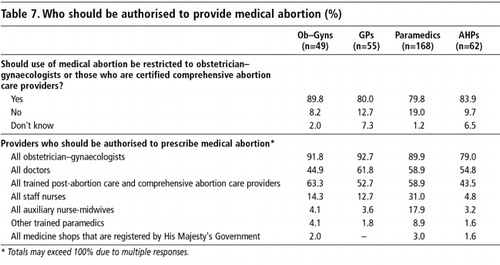

All the respondents except chemists were asked whether the provision of medical abortion drugs should be restricted to obstetrician-gynaecologists, or if all those who are certified as comprehensive abortion care providers could provide it. The large majority of respondents agreed with the view that both obstetrician-gynaecologists and other approved comprehensive abortion care providers should be allowed to provide medical abortion. (Table 7)

Obstetrician-gynaecologists received the highest ratings as possible providers (79-93%) from all categories of respondents, including the obstetrician-gynaecologists themselves (92%). However, the majority of providers in all categories demonstrated liberal views in that they also approved medical abortion provision by GPs (57%) and any trained post-abortion care and comprehensive abortion care providers (56%). That all staff nurses should also be allowed to provide medical abortion was mentioned by a higher percentage of paramedics (31%) than other respondents. Moreover, 18% of the paramedics also favoured auxiliary nurse-midwives prescribing medical abortion. On the other hand, only 12-14% of the obstetrician-gynaecologists and GPs thought that staff nurses could also be authorised to provide mifepristone-misoprostol.

Most respondents opined that health providers certified to prescribe medical abortion should also be able to provide surgical abortion since women could return with incomplete abortion or other complications that require surgical back-up. About 13% of the paramedics disagreed, arguing that they trusted the effectiveness of medical abortion to ensure a complete abortion. A few said it would be impossible for all paramedics to have surgical facilities in their clinics. None suggested that women could be referred elsewhere for surgical follow-up if necessary.

In order to restrict the provision of medical abortion to qualified and trained practitioners and to prevent unsafe use of mifepristone and misoprostol, the majority of providers thought that the drugs should be made available with a doctor's prescription only and that chemists' shops and other outlets selected to keep stocks of the drugs should not provide them without a prescription. The idea of expanding access to medical abortion through NGO clinics, for instance those of the Family Planning Association of Nepal, came from a significant proportion of providers, including the medical professionals (21%).

Discussion

The present study has shown that there are various types of allopathic and indigenous medicines on the Nepalese market for menstrual regulation and most are also being prescribed by private providers and chemists and purchased by women for inducing abortion. Because of the open border with India, all these products enter Nepal easily. During the course of this study, the research team were able to purchase most of these medicines from chemists in the border towns and the Kathmandu valley without difficulty. Mensolex, a homeopathic drug produced in India, is a good example, which has clear instructions on how to use this drug for abortion and is sold openly on the Nepalese market. We have found no studies that examined the safety and efficacy of such drugs for inducing abortion.

The low level of awareness about mifepristone and misoprostol among most of the health care providers interviewed is due to the fact that neither of these drugs has officially been introduced in Nepal for medical abortion. It is surprising that mifepristone has not yet filtered into the Nepalese market like other drugs from India for the purpose of abortion. Use of misoprostol for the prevention of post-partum haemorrhage has recently been piloted in Banke district in Nepal under the Nepal Family Health Program (Personal communication, Lila Khanal, Nepal Family Health Program, Kathmandu, August 2005) and depending upon the results of the pilot project, the Ministry of Health and Population (MoHP) will decide whether to include misoprostol in its Safe Motherhood Program (Personal communication, Dr Ganga Shakya, Family Health Division, MoHP, Kathmandu, August 2005).

It was highly encouraging to find positive responses from providers and paramedics regarding the potential for introducing mifepristone and misoprostol in Nepal and the willingness of chemists to stock the drugs. The keen interest shown by almost all the obstetrician-gynaecologists and paramedics in prescribing medical abortion themselves is a very positive sign. Few providers expressed concern about the possible misuse of medical abortion instead of contraception. Such concerns can be avoided through advocacy and sensitisation programmes among the health providers and adequate pre- and post-abortion counselling for women seeking a medical method of pregnancy termination.

Registration of available brands of mifepristone and misoprostol is the key to introducing medical abortion in Nepal and we recommend that the appropriate steps to do so be taken as soon as possible. Conducting a pilot study first in one district having an approved comprehensive abortion care service will be necessary to assess the acceptability of medical abortion among women and service delivery aspects. Thereafter, the provision of medical abortion can be initiated through all government-approved comprehensive abortion care sites. This will provide women with an alternative to MVA that is safe, simple and effective. Subsequently, medical abortion services can be expanded through other government and private health institutions, which may be willing to provide medical abortion services only. The advantages of medical abortion with mifepristone and misoprostol are clear for both women and providers in Nepal and information and advocacy messages for promotion of medical abortion in the country should be developed and dissemination begun alongside its introduction.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Ipas for entrusting CREHPA to undertake this study. We are grateful to Dr Bela Ganatra, Regional Advisor, Ipas, for her continued encouragement to the team and for useful comments on this paper.

Notes

* The Indian government approved the use of mifepristone for medical abortion in 2002, and it is being marketed by several Indian pharmaceutical companies. Misoprostol was already available for treating gastric ulcers. Use of medical abortion in India in the private sector has been increasing and the Government of India is now formulating guidelines for its use in the public sector.Citation17

References

- Ministry of Law, Justice and Parliamentary Affairs. New recommendation on Muluki Ain (National Civil Code) 11th Amendment 2002, Kathmandu: Ministry of Law, Justice and Parliamentary Affairs, 1997.

- Center for Research on Environment Health and Population Activities. Women in Prison in Nepal for Abortion. A Study on Implications of Restrictive Abortion Law on Women's Social Status and Health. 2000; CREHPA: Kathmandu.

- G Shakya, S Kishore, C Bird. Abortion law reform in Nepal: women's right to life and health. Reproductive Health Matters. 12(24 Suppl): 2004; 75–84.

- S Thapa. Abortion law in Nepal: the road to reform. Reproductive Health Matters. 12(24 Suppl): 2004; 85–94.

- Ministry of Health Nepal, New Era, ORC Macro. Nepal Demographic Health Survey 2001. Calverton MD. 2002.

- Ministry of Health. Maternal Mortality and Morbidity Study. Family Health Division, Department of Health Services, Ministry of Health. 1998.

- A Tamang, M Puri. Unsafe abortions, abortion law and their implications on women's health and lives in Nepal. Nepal Population Journal. 9(8): 1999; 20–30.

- Center for Research on Environment Health and Population Activities. Management of Abortion Related Complications in Hospitals of Nepal - A Situation Analysis. 2000; CREHPA: Kathmandu.

- A Tamang. Induced abortions and subsequent reproductive behavior among women in urban areas of Nepal: social change, issues and perspectives. Journal of the Council for Social Development. 26(3/4): 1996; 271–285.

- Center for Research on Environment Health and Population Activities. Understanding Culturally Specific Pregnancy Prevention Practices following Unprotected Intercourse among Young Couples of Different Ethnic Communities of Nepal. 2002; CREHPA: Kathmandu.

- A Rana, N Pradhan, G Gurung. Induced septic abortion: a major factor in maternal mortality and morbidity. Journal of Obstetric and Gynaecologic Research. 30(1): 2004; 3–8.

- Ministry of Health. Safe Abortion Service Procedure. 2003; MoH, Department of Health Services, Family Health Division: Kathmandu.

- Family Health Division, Ministry of Health and Population. Comprehensive abortion care listed sites. 2005; Ministry of Health and Population: Kathmandu.

- Winikoff B, Sivin I, Coyaji KJ, et al. The acceptability of medical abortion in China, Cuba and India. International Family Planning Perspectives. 1997; 23(173): 78–89.

- K Coyaji, B Elul, U Krishna. Mifepristone-misoprostol abortion: a trial in rural and urban Maharashtra, India. Contraception. 66: 2002; 33–40.

- Gynuity Health Projects. Providing Medical Abortion in Developing Countries: An Introductory Guidebook. 2004; Gynuity: New York.

- Ipas. Concept paper on research on reach of medical abortion in India. India. Pune: Ipas, (year not known).