Abstract

Small island exigencies and a legacy of colonial jurisprudence set the stage for this three-year study in 2001-2003 of abortion practice on several islands of the northeast Caribbean: Anguilla, Antigua, St Kitts, St Martin and Sint Maarten. Based on in-depth interviews with 26 physicians, 16 of whom were performing abortions, it found that licensed physicians are routinely providing abortions in contravention of the law, and that those services, tolerated by governments and legitimised by European norms, are clearly the mainstay of abortion care on these islands. Medical abortion was being used both under medical supervision and through self-medication. Women travelled to find anonymous services, and also to access a particular method, provider or facility. Sometimes they settled for a less acceptable method if they could not afford a more comfortable one. Significantly, legality was not the main determinant of choice. Most abortion providers accepted the current situation as satisfactory. However, our findings suggest that restrictive laws were hindering access to services and compromising quality of care. Whereas doctors may have the liberty and knowledge to practise illegal abortions, women have no legal right to these services. Interviews suggest that an increasing number of women are self-inducing abortions with misoprostol to avoid doctors, high fees and public stigma. The Caribbean Initiative on Abortion and Contraception is organising meetings, training providers and creating a public forum to advocate decriminalisation of abortion and enhance abortion care.

Résumé

Les particularités des petites îles et une jurisprudence coloniale héritée forment le décor de cette étude réalisée en 2001-2003 sur la pratique de l'avortement dans plusieurs îles du nord-est des Caraïbes : Anguilla, Antigua, St Kitts, St Martin et Sint Maarten. Des entretiens avec 26 médecins, dont 16 réalisaient des avortements, ont montré que les médecins pratiquent des avortements en contravention avec la loi, et que ces services, tolérés par les autorités et légitimisés par les normes européennes, représentent l'essentiel des services d'avortement. L'avortement médicamenteux était utilisé sous surveillance médicale et par automédication. Les femmes voyageaient pour préserver leur anonymat, et pour accéder à une méthode, un praticien ou une structure médicale de leur choix. Parfois, elles se contentaient d'une méthode moins acceptable si elles ne pouvaient se permettre une méthode plus confortable. La légalité n'était pas le principal facteur de choix. La plupart des praticiens trouvaient la situation satisfaisante. Néanmoins, les données de l'étude indiquent que les lois restrictives entravaient l'accès aux services et compromettaient la qualité des soins. Si les médecins ont peut-être la possibilité et les connaissances requises pour pratiquer des avortements clandestins, les femmes n'ont pas de droit légal à ces services. Les entretiens suggèrent qu'un nombre croissant de femmes avortent seules avec du misoprostol afin d'éviter les médecins, les honoraires élevés et la stigmatisation. L'Initiative des Caraïbes sur l'avortement et la contraception organise des réunions, forme des praticiens et crée un forum en faveur de la dépénalisation de l'avortement et de l'amélioration des soins.

Resumen

Las exigencias de islas pequeñas y un legado de jurisprudencia colonial crean el marco para este estudio de tres años (2001-2003) sobre la práctica de abortos en Anguilla, Antigua, San Kitts, San Martin y San Maarten. Mediante entrevistas a profundidad con 26 médicos, 16 de quienes efectuaban abortos, se encontró que los médicos autorizados para ejercer realizan abortos de manera rutinaria en contravención de la ley. Estos servicios, tolerados por los gobiernos y legitimados por normas europeas, son el pilar de la atención del aborto en estas islas caribeñas. El aborto con medicamentos estaba practicándose bajo supervisión médica y mediante automedicación. Las mujeres viajaban para encontrar servicios anónimos y para tener acceso a determinado método, prestador de servicios o establecimiento de salud. A veces se conformaban con un método menos aceptable si no podían pagar por uno más cómodo. La legalidad no fue el factor determinante para el método seleccionado. Aunque la mayoría de los prestadores de servicios de aborto aceptaban la situación actual como satisfactoria, nuestroshallazgossugieren que las leyes restrictivas obstaculizan el acceso a los servicios y comprometen la calidad de la atención. Mientras que los médicos tienen la libertad y los conocimientos para practicar abortos ilegales, las mujeres no tienen ningún derecho legal a estos servicios. Las entrevistas indican que un número creciente de mujeres están autoinduciendo abortos con misoprostol para evitar los médicos, las altas tarifas y el estigma público. La Iniciativa Caribeña de Aborto y Anticoncepción está organizando reuniones, capacitando a los proveedores y creando un foro público a favor de la despenalización del aborto y el mejoramiento de estos servicios.

Abortion laws in the Caribbean derive from a legacy of colonial jurisprudence and range from the most restrictive to the most liberal in the world. Travel between countries is a constant feature of life in most of the region. This paper reports on a study of current abortion provision, lawful and unlawful, within and across borders in the northeast Caribbean, using these historical and geographical markers as its frame, with particular attention to the exigencies of living on a small island and the influence of European laws on abortion providers.

Our initial criteria for choosing the islands on which to conduct this research included small size, geographical proximity, fluid borders and diverse legal systems. The two-country island of Sint Maarten (Netherlands Antilles) and St Martin (France) fit these criteria and served as a good starting point to assure inclusion of non-independent countries, often excluded from regional studies. We then added countries one by one as our interviewees provided names of abortion providers on other islands. By following those leads back and forth between islands, we arrived at a five-country case study.

The countries we included were Anguilla, a British Overseas Territory; Antigua, one of the two islands in the state of Antigua and Barbuda, independent since 1981; St Kitts, one of the two islands in the state of St Kitts and Nevis, independent since 1983; St Martin, French Overseas Department of Guadaloupe; and Sint Maarten, Kingdom of the Netherlands Antilles. Not counting the significant flow of unregistered migrants, approximately 200,000 people live in the five countries. Antigua, St Martin and Sint Maarten are frequent destination points for migrants, both legal and illegal, from the entire Caribbean region, especially Haiti, Dominican Republic, Guyana, Dominica and Jamaica.

Our study design is atypical in that it examines abortion practices in juridically separate health systems as one service network and includes interviews with licensed health professionals working in authorised medical facilities who provide abortions, whether they are legally permitted to do so or not. Since our ultimate aim was to contribute to an improvement in abortion care in the region, we sought to identify practitioners who were qualified, informed and potentially influential.

Abortion laws in the five countries reflect the colonial history and current political status of each country. Anguilla is largely autonomous in fixing its own laws. Antigua-Barbuda and St Kitts-Nevis are self-governing. As former British colonies, they operate against a background of English common law, some but not all of which has been changed. As Commonwealth members, certain judicial decisions taken in England may be applied. St Martin is governed by current French law. Sint Maarten's laws are set by the Netherlands for foreign policy and in the Antilles for most other matters, including health legislation.Footnote*

Methodology

Identifying and conducting in-depth interviews with the main abortion providers and a representative sample of other physicians and health authorities in each country took place over a period of three years (2001-2003). Repeat interviews and convergence of material from different sources helped to assure validity of findings. We explained this was a study of abortion practices in the Caribbean aimed at laying the groundwork for regional cooperation to improve care; anonymity was assured. Eighty per cent of the doctors and nearly all the other health professionals were comfortable with being recorded; for the rest, responses were noted by hand. The interviews with physicians covered professional background, abortion law and policy, abortion facilities and methods used by them and by others on the island, obstacles to optimal care, risks and complications, specific issues related to migrant women and referrals within and across borders.

Our final sample of physicians included 12 obstetrician-gynaecologists, 11 family practitioners and three physician government administrators, of whom 16 were performing abortions, nine of them obstetrician-gynaecologists and seven family practitioners. Two of the 16 abortion providers were women. Seven did abortions only in a hospital, two in a hospital and their private office, and seven only in their private office. They were based in five government hospitals and two private hospitals. Of the ten who were not performing abortions, five had been trained and done so in the past.

Half of the abortion providers were trained in Europe or North America; the other half at the University of West Indies (Barbados and Jamaica campuses). Most of the Caribbean-trained physicians had done some or most of their post-graduate work in Europe, the United States or Canada. Given the laws on each island, only two of the 16 abortion providers were complying with legal guidelines. We have not specified the number of abortion providers in each country or their location, and use a generic masculine pronoun to refer to all physicians in order to assure anonymity. We present interviews as one set with physicians from Anguilla, Antigua and St Kitts, juridically similar contexts, to camouflage identities of individual abortion providers where stigma is especially strong. We also interviewed more than 30 health professionals, advisors or government officials, including five family planning workers (three of whom were nurse-midwives), seven government officials (including a Minister of Health and an Attorney General) and five pharmacists. We asked everyone to speak about their knowledge and opinion of abortion law and practice in their country.

We discussed the research at the onset and on a number of other occasions with women community leaders, government gender affairs officers and seven women's groups. Those meetings were critical to our project as a check on the relevance of the study to women's concerns, as a way to transmit research findings to their rightful beneficiaries and as part of the process of building an inter-island network of women committed to working for safe abortion in the Caribbean.

Sint Maarten: institutionalised tolerance of abortion

Upon arrival in Sint Maarten, we met with the staff of the Women's Desk, a government community centre. Three staff members informed us:

“Abortion is illegal in Sint Maarten…No, the law is not a problem… Everyone knows who is doing them. We don't talk about it, we can't talk about it since it is illegal and we are a government agency. Abortion… is a taboo here.”

A family doctor elaborated:

“Abortion is illegal, but tolerated. When Holland changed the law, the Dutch Antilles never put the new law into effect, but abortion is very tolerated… because physicians know the Dutch law.”

One of the main providers of aspiration abortion described how the central government of the Netherlands Antilles, located in Curaçao, not only tolerates abortion but also visits facilities to check quality of care:

“We have a verbal agreement with the Curaçao Ministry of Health. An inspector came to visit from Curaçao to make sure we were doing the procedure properly. I'd been really worried about their visit and then all they did was check my facility and ask about my technique. They know it is a needed service.”

Another general practitioner was suspicious of the government's motives:

“Everyone knows it is done. It's an institutionalised toleration system. Safe abortions are available, also by gynaecologists at the hospital… The Health Department here is totally aware of the situation but they don't acknowledge it. They like to keep the situation illegal because then they could catch you. If anything goes wrong, they could prosecute… it's a taboo situation… But no, I'm not for legalisation, that would mean more controls, more delays. The system works fine the way it is.”

Does this “institutionalised tolerance” assure women access to services? We asked two of the hospital gynaecologists whether they set any conditions on a woman wanting to terminate a pregnancy and, if so, which ones. Their replies were revealing:

“I try to discourage women from having an abortion unless they have heavy social reasons. If a woman has six or seven or eight children, okay, but if she has only two or three then I don't do the abortion.”

“Officially we cannot do it unless there's a serious medical reason… So some women go to family physicians on the outside… and some go to the French side (of the island) where it is legal, and often these days what you see more is that they use Cytotec…Footnote* We are getting a lot of patients now with incomplete abortions.”

This doctor blames the law that women are ending up in the emergency room with incomplete abortions. Most of them had self-administered Cytotec tablets to avoid confronting barriers to abortion care in medical facilities. Asked if he was in favour of legalisation, he declared:

“I think that a woman has a right to choose, and if you think women have a right to choose, then you better make it legal so that she can do it in a better way.”

Crossing the border to St Martin: legal within fixed guidelines

Professionals and the people of Sint Maarten are very much aware that hospital abortion is legal and available just a walk away across the border in St Martin where, due to universal French medical coverage, health care is accessible to those who lack health insurance. At the hospital, French abortion law determines the type of service they will receive. St Martin is the only country in our sample that provides medical abortion with mifepristone, admininistering it under tight regulations in combination with the more widely available misoprostol. According to a hospital gynaecologist:

“The French law is very clear. All pregnancy terminations are done at the hospital. All eligible women, 30-40% of the total, get the medical method… Most prefer it, though some prefer early surgical abortion because they know the pills are not so easy. All aspirations are performed electrically under general anaesthesia.”

This physician did not know physicians working on the Dutch side, although he did know where women could go off-island for second trimester abortions:

“Over 14 weeks, we just say we cannot do it here, but under English law they can do it later than under French law, so maybe in (name of island), we're not sure, maybe they can go over there.”

Women could and did go “over there” , and so did we, where we learned that current English law did not, in fact, hold on the independent neighbouring island. The St Martin gynaecologist freely offered us the name of an off-island practitioner, while physicians elsewhere eventually gave us the names of providers of illegal abortions in St Martin.

Surgical abortion in a private office is against French law. In a certain sense, private abortions are more transgressive than those on the Dutch side of the island because: “The French law (unlike applications of Netherlands Antilles law) is very clear.” One general practitioner, more hesitant than most to discuss his practice, admitted he had been doing abortions in St Martin for many decades, long before they were authorised, even in hospitals:

“I do aspirations by electric suction here in my office, I've got the machine, it's quick… I do them only to eight weeks. If they are further along, I send them to the hospital.”

Another private practitioner was firmly against doing aspiration abortions in a private office but felt quite comfortable giving drugs to induce abortion, even if it entailed procuring them under false pretenses:

“Never an aspiration in a private office, never, it is too dangerous… Cytotec? It is a problem because the box has 60 tablets… I give just two or three or four, so I buy it at the pharmacy as if it is for me (laughs)… When the pregnancy is 10-12 weeks it works very well… I tell them to put the tablets in vaginally - morning, evening, morning, evening for two days - then they come back to me and I check and usually they are done and then they don't have to go to the hospital.” Footnote*

Avoidance of the hospital was cited again and again as women's main reason for going to private practitioners, regardless of the fact that the abortions provided were illegal. Attending the French hospital meant risk of public exposure, general anaesthesia for aspiration abortions and usually some payment for non-residents.

Migrant women without legal residence papers were said to avoid public facilities either by going to private doctors or, increasingly, by buying misoprostol from underground distributors who carry the drug from one island to another. In a group interview with ten unregistered migrants, each of whom had had from one to four misoprostol abortions, there was a consensus that it was best to do your own abortion - despite sangró mucho, mucho dolor (lots of blood and pain) - to avoid the cost and visibility of going to a doctor.Footnote*

Anguilla, Antigua and St Kitts: circumventing the law

Doctors in St Martin and Sint Maarten told us that women come for abortions from other islands to escape stigma and punishment at home. Anguilla, with the smallest population in our sample, is only a 20-minute, US$20 round-trip boat ride away. A physician in Anguilla told us how women automatically flee home if they need an abortion:

“Patients beg us not to write the truth on their medical charts. If their church finds out they have had an abortion, they'll be expelled from the church. There is no privacy in the hospital, so once I tell a woman she's pregnant, I don't see her again, she will go to St Martin…French or Dutch side.”

We knew the Anguilla government had recently liberalised their abortion law, so we asked the medical director of the hospital whether there was an increase in service provision. His response was clear: “There is a new law here, but it is not being implemented.”

We were able to identify abortion providers on the island, but they felt no greater liberty to practice openly than before the law had been amended. In a meeting with the Attorney General, we came to a better understanding of the social climate:

“The change in law was not intended to open up abortion for women here. It was recognised that there are certain circumstances that may be dangerous for the mother… The culture of Anguilla would not permit abortion on demand. This is a Christian society. Laws from Great Britain are not our laws.”

Although current British abortion law does not prevail in British Overseas Territories, it is called upon by some physicians to justify abortions. A gynaecologist who has worked on different islands explains:

“Basically there are two sets of laws. The dependent British territories have their own intrinsic laws that are passed by the government of the island. And then one can sort of operate under the mother-country laws. So in order for me to do a termination of pregnancy, I have to do it under British law… As for the independent English-speaking Caribbean countries, well, they too come out of the British inheritance. It's not legal in most of them, except Barbados and Guyana, but it's tolerated because nobody is going to prosecute a doctor.”

Clearly, doctors are privileged transgressors of the law. We asked a nurse in Antigua who had learned how to do manual vacuum aspiration whether she performed abortions. She laughed and shook her head: “Oh no. We nurses have a saying: ‘What will save a doctor, will hang a nurse!’”

“There was a time when there were all these backstreet abortionists. One lady told me she went to a fisherman! What does a fisherman know about human anatomy? That's how desperate she was… People used to end up with sepsis, really sick, and when I say sick, I've seen times you had to stay outside the room the smell was so bad. You don't see that anymore. Doctors realised that people were dying, or becoming infertile, and they decided, well, it was inhumane to let people suffer like that…Now people go to the doctors and the doctors help them… The church, they don't say anything about it because it isn't legal… but it's not done as a cloak-and-dagger thing, it's done more or less openly, and safely.”

If abortion is so open in Antigua, why does it remain illegal? We asked practitioners about obstacles to legal reform, and the response was always the same: “This is a very Christian society.” Nonetheless, as one obstetrician-gynaecologist elaborated:

“Technically abortion is illegal in Antigua, but the law hasn't been a problem… We (physicians) have gone to the government trying to seek legislation, and basically the government has backed off. They said, ‘Look, it hasn't been a problem, what we do is turn a blind eye, but to legislate that abortion would be legal would cause too much problem with the Church.’ This is a very Christian society.”

A health administrator of an NGO agreed that the country was not ready for legal reform. He even expressed his concern that efforts to change the law could jeopardise existing services:

“If we try to push this legalisation business, we are just going to push the Church, the conservatives, the whole society against us, and the safe abortions that are happening are going to stop…The Church knows about this… I'm not going to ruin what works well here because our concern is the health of our women… Down the line, legal. Right now, safe. This is our highest moral principle.”

Whether by way of moral or scientific principles, abortion practitioners emphasised the legitimacy, if not legality, of abortion provision. When asked whether the criminal prohibition concerned him, a family doctor responded with the force of professional authority:

“We are medical professionals. We have the French Canadian Medical Association (opens his top drawer and pulls out a medical journal from the University of Montreal Citation7 with an article on misoprostol abortion protocols). You see, the medical profession respects us.”

Controversies and constraints

On every island, misoprostol was the most controversial abortion method. Some practitioners considered it dangerous and others a safe alternative to surgical abortion. A family doctor, who said he would not do aspiration abortions directly, finds them easy after the woman has used misoprostol, since the cervix is then amply dilated. He explained his decision to supervise women's use of misoprostol:

“My first two years of practice, I refused to do it, and then they used to go right and left and come in with complications, and I said, let me help them, under my supervision… I have a small suction machine for the 20-30% who need an aspiration. I don't want them to bleed, bleed, bleed.”

Another physician, a long-time provider of first trimester aspiration abortions, was dismayed by the increase in misoprostol use, especially when the drug was sold by the tablet for profit by pharmacists:

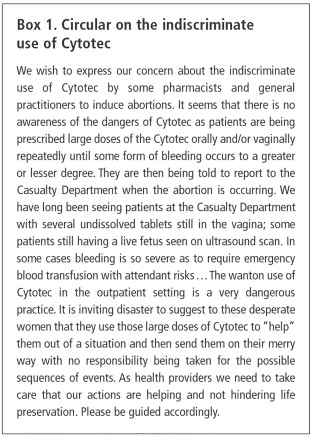

“Aspiration abortion (up to 8 weeks) is safer than walking across the street… I used to do up to six a day, but now it's cut in half due to all the Cytotec… Pharmacists sell the tablets individually; they mark the price way up… We know because there are lots of incomplete abortions showing up at the emergency room… The gynaecologists at the hospital sent around a circular to all the pharmacists telling them to stop selling it.”

The circular was signed by the three gynaecologists of the government hospital (Box 1). It is careful to denounce indiscriminate use, wanton use, large doses, late use (implied by reference to a live fetus) and no reponsibility. On a subsequent visit to the island we asked one of the signatories whether correct use of misoprostol would make it acceptable, and he confirmed that the problem was not misoprostol per se, but lack of supervision. He himself did not hesitate to advise women for whom a surgical abortion was too expensive to try the tablets:

“Women have come to me and said, ‘Doctor, I want to have a termination but I cannot afford the $1400 Eastern Caribbean [=US$560]). What can I do?’ And I've said, ‘This is what you can do, you can go to the pharmacist, they can give you these tablets, and if you have any problem you come back and see me.”

He made sure to date their pregnancies and to tell them how many tablets to take. What he found more disconcerting than misoprostol abortions was the systematic performance of unnecessary dilatation and curettage (D&C) for early abortions and post-abortion bleeding, specifically at the government hospital where most women go. He explained how he performed aspiration abortions at the private hospital, where he had a certain degree of freedom, but was obliged to do D&Cs for the same indications at the government hospital because simpler procedures were associated with illegal pregnancy termination:

“At the government hospital we do a D&C because we don't have the instruments to do aspirations… Since it's a government hospital and terminations should not be done, they wouldn't order the instruments… Most patients go to the government hospital because the doctor's fee, the anaesthesiologist's fee, all of those the patient doesn't have to pay.”

We were told that on another island they also perform D&Cs; however, upon further enquiry we realised that they were, in fact, doing aspirations with a suction machine. The D&C terminology was technically inaccurate but legally irreproachable because the instruments were recognised for treatment of miscarriage.

Miscarriage is the most common and thinly disguised diagnosis for incomplete abortion. Sometimes doctors use the term on medical charts to camouflage a pregnancy termination. An obstetrician-gynaecologist on one island told us:

“On the operating list I write ‘removal of retained products of conception’ so it looks like a miscarriage.”

Others call abortions miscarriages to facilitate reimbursement of costs for women. One hospital physician explained:

“Insurance companies cover miscarriage but not incomplete abortion. The company will call the doctor to go over the form - and they refuse coverage if the woman can't show she was being followed by a physician for a pregnancy prior to the miscarriage.”

Also in private offices without insurance coverage, physicians share euphemistic language with their patients. A family doctor in Sint Maarten prefers the term “menstrual regulation” to “abortion” , whether by aspiration or misoprostol. The term menstrual regulation is well-known in other parts of the world,Citation8 and this doctor is satisfied with the procedure:

“If you don't do a pregnancy test and you do a suction, it's not a suction for abortion, it's menstrual regulation. Same thing with Cytotec, it's not an abortion, it's menstrual regulation… usually it works, and maybe it was really not an abortion at all, just a hormonal imbalance.”

Another physician insisted: “I don't do abortions…only medication” . An obstetrician-gynaecologist likewise avoided the word abortion in his consultations with women:

“Women ask for something to ‘bring on their period’. I have drugs to ‘bring on their period’, and don't even mention abortion or pregnancy termination.”

Many health professionals expressed caution about their language, not only with women but also with colleagues, especially in writing out a referral for abortion. A family doctor who recently arrived on one of the islands told how he was making referrals to the gynaecologist for “pregnancy termination” until someone told him: “Just write down stomach pain.”

Discussion

Such linguistic codes betray the taboo of abortion, and also the complicity among doctors and between doctors and women patients. And yet, this taboo is harsher for women, who fear they'll be expelled from the church, than for abortion providers whose government turns a blind eye or sends a medical inspector to make sure they are doing the procedure properly. It would be wrong, however, to conclude that the physicians we interviewed are relaxed about breaking the law; some are aware that if anything goes wrong, the government could prosecute them, and others are ready with their defence should they ever be arrested. Restrictive laws reinforce social stigma. Both abortion seekers and abortion providers strategise to avoid punishment while trying to obtain or give the best possible care.

Women travelled to find anonymous services, and also to access a particular method, provider or facility. Sometimes they settled for a less acceptable method if they could not afford a more comfortable one. Significantly, legality was not the main determinant of choice. Women from Anguilla look for an abortion provider off-island to avoid condemnation at home. It costs only US$20 round-trip for a short boat ride from Anguilla to St Martin or Sint Maarten. Women from the Netherlands Antilles side may go to the French side if the abortion is less expensive, or if they want a medical abortion with mifepristone. Women from the French side sometimes go to the Dutch side if they prefer an aspiration abortion in a physician's office to a hospital procedure under general anaesthesia, or they get the same procedure at home from a private doctor practising illegally. Women from St Kitts often go off-island in search of anonymity, and women from Antigua seeking an abortion for a second trimester pregnancy, like women from all the islands, are likely to go to the one provider who does them.

Most of the physicians and health authorities we interviewed believe that abortions in their countries are safe and accessible and therefore see no reason for legal reform. We heard many times that the law was not a problem because abortion was done under medical supervision and was at least “relatively safe” or “quite safe” , even “safer than walking across the street” , whereas legalisation would bring “more controls, more delays” . Although a few practitioners were outspoken in advocating abortion law reform, most accepted the current situation as satisfactory. Those practising within authorised guidelines in French St Martin likewise accepted the limits of their services, informally referring women off-island for second trimester abortion.

However, our findings suggest that restrictive laws were hindering access to services and compromising quality of care. Whereas doctors may have the liberty and knowledge to practice illegal abortions, women have no legal right to those services. It is thus the doctor who personally decides whether or not to serve any particular woman. Women seem to be self-inducing abortions with misoprostol more often than before to avoid doctors, high fees and the public exposure of institutional care. Some of them need emergency back-up care for incomplete abortion, as several informants reported. We learned that such post-abortion care is compromised by restrictive laws in certain government hospitals where D&Cs, rather than the safer aspiration procedures, are performed because buying abortion equipment was not allowed.

Many physicians told us that they commonly misrepresent procedures and outcomes on medical charts, a camouflage aimed at protecting both themselves and women. However, if something goes wrong, there is no reliable documentation, clinical accountability or medical responsibility for patient well-being.

Nonetheless, licensed physicians are routinely providing abortions in contravention of the law, and their services are clearly the mainstay of abortion care on this set of islands. They justify systematically breaking the law through reference both to women's needs and to their connection, initially through medical education and training, with legal abortion in Britain, France and the Netherlands. Together with the exigencies of small island geography, this historical connection distinguishes the context of abortion provision in Caribbean countries from that in continental Latin America, (under which the Caribbean generally falls in global reports), which may give it common ground with island countries and former colonies in other regions.

Prohibitive 19th century European abortion laws were imposed on Caribbean colonies over a century ago and then discarded in Europe, where women now have access to safe, legal induced abortion. Caribbean health providers have moral as well as medical reasons to use their competence in the service of their own populations. Such conscientious transgression of unhealthy laws testifies to their determination and alliance with women.

Postscript

After completion of the research, the Caribbean Initiative on Abortion and Contraception presented the findings to the participating health professionals, women's groups and policymakers and recommendations and implementation plans were drafted. The first outcome was an expert meeting in 2003 on abortion and contraception at the University of Picardie Jules Verne, Amiens, France, co-sponsored by Saludpromujer, University of Puerto Rico. The meeting took place in Europe to facilitate open exchange, especially for Caribbean abortion providers working under restrictive laws. Representatives from the five research sites and Puerto Rico presented papers, as did European and international experts. In the Caribbean, a series of meetings was organised (with support from Mama Cash) to set up a Women's Inter-Island Working Group. At the same time, we developed collaborations with Gynuity Health Projects, Ibis Reproductive Health, Ipas and Population Council. An intensive clinical training programme was set up, run by Dr Marijke Alblas and financed by the World Population Foundation, for teaching manual vacuum aspiration and use of local anaesthesia in hospitals (where this is beginning to replace D&Cs), as well as educational sessions for doctors, nurses, family planning staff, women's groups, high schools students and policymakers.

In May 2005, we organised a conference in Antigua-Barbuda in collaboration with the above organizations on “Safe Abortion in the Caribbean: From Law to Practice” . Participants came from 14 Caribbean countries including Anguilla, Antigua-Barbuda, Barbados, Curaçao, Dominica, Guadaloupe, Guyana, Jamaica, St Eustatius, Sint Maarten, Puerto Rico, St Kitts-Nevis, St Lucia, and Trinidad-Tobago. The meeting covered legal and clinical issues and culminated in a Declaration of Health Professionals, Scientists and Advocates For Decriminalisation of Abortion in the Caribbean (available on internet) and with the formation of a regional Working Group of Abortion Providers. By interlacing research, training and action, we hope to continue to make known the realities of abortion in the Caribbean while creating a public forum to de-stigmatise, decriminalise and enhance abortion care.Footnote*

Acknowledgments

For more complete data and theoretical elaboration of this article, seeCitation1 below. The research was authorised by the Institutional Review Board of the University of Puerto Rico Medical Sciences Campus (#9080105). It falls within the Caribbean Initiative on Abortion and Contraception, a project co-directed by the researchers and supported by grants from an anonymous donor and the Jesse Smith Noyes Foundation to Saludpromujer, School of Medicine, University of Puerto Rico, and by faculty of the University of Picardie Jules Verne, Amiens, France. Our gratitude for the insight, generosity and honesty of health professionals working for women's well-being in Anguilla, Antigua, St Kitts, St Martin and Sint Maarten.

Notes

* For texts of laws, including English translation of the French and Netherlands Antilles penal code abortion articles, see Working Paper.Citation1 For extensive analysis of Commonwealth abortion law, see Cook and Dickens.Citation2Citation3

* Cytotec is the brand name in the Caribbean of misoprostol, that is used extensively in many countries to induce (and self-induce) abortion. The earliest reports came from Brazil,Citation4 and were followed by numerous clinical studies of safety and efficacy,Citation5 and scientific meetings to agree on safe protocols.Citation6

* In 2004, after completion of this study, physicians in private practice with hospital affiliations were authorised by French law to supervise medical abortion until 49 days LMP with the fixed two-drug protocol, mifepristone and misoprostol. Aspirations remain legal only at the hospital.

* Due to the delicacy of the subject, the women did not want to speak to us directly but talked to a trusted nurse, who told them about the study. They said they didn’t dare to show their faces in a conversation about abortion since it is illegal.

* For information on the Caribbean Initiative, see: <www.saludpromujer.org>.

References

- Pheterson GI in collaboration with Yamila Azize. Safe Illegal Abortion: An Inter-Island study in the Northeast Caribbean. A Working Paper of the Caribbean Initiative on Abortion and Contraception. In English, Spanish and French at. <www.saludpromujer.org>.

- RJ Cook, BM Dickens. Abortion laws in Commonwealth countries. International Digest of Health Legislation. 30(3): 1979; 395–502.

- RJ Cook, BM Dickens. Issues in Reproductive Health Law in the Commonwealth. 1986; Commonwealth Secretariat: London.

- SH Costa, MP Vessey. Misoprostol and illegal abortion in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. Lancet. 341: 1993; 1258–1261.

- Special Issue Medical Abortion. Journal of the American Medical Women's Association. 55(3 Supplement): 2000

- Reproductive Health Technologies Project and Gynuity Health Projects. Consensus Statement: Instructions for Use - Abortion Induction with Misoprostol in Pregnancies up to 9 Weeks LMP. Expert Meeting on Misoprostol, Washington DC. 28 July 2003.

- Le Cahiers de Formation Médical Continu. Obstétrique-Gynécologie. Université de Montréal. 16 May 2001.

- FS Begum. Saving lives with menstrual regulation. Planned Parenthood. 1993; 30–31.