Abstract

Medical abortion is safe and effective and has been approved for use in early termination of pregnancy in South Africa since 2001. The Department of Health is currently considering its introduction in the public health sector. The attitudes of women seeking abortion and of health care providers towards medical abortion have not previously been described. Data were derived from a quantitative survey of 673 women attending abortion services in the provinces of Gauteng, Mpumalanga and the Western Cape. In-depth interviews in Soweto and Cape Town were conducted with 20 public health doctors, nurses, a social worker and facility managers, and in Cape Town with four provincial policymakers. Although medical abortion was not yet being offered, 21% of women interviewed were early enough in pregnancy (eight weeks or less) to be eligible for medical abortion. Access to health facilities, including those for abortion, was reasonable for urban women but more limited for rural women. Rural women also incurred greater travel costs to reach a facility. Most women thought medical abortion would be acceptable and would have been willing to try it, had it been available. Policymakers and providers were supportive, as they felt medical abortion could relieve the burden on current services. How to increase access to abortion services in rural areas needs to be addressed.

Résumé

L'avortement médicamenteux est sûr et efficace et son utilisation a été approuvée pour l'interruption précoce de grossesse en Afrique du Sud en 2001. Le Département de la santé envisage son introduction dans le secteur de la santé publique. Les attitudes des femmes souhaitant avorter et des prestataires de soins de santé à l'égard de l'avortement médicamenteux n'ont jamais été décrites. Les données proviennent d'une enquête quantitative auprès de 673 femmes s'étant rendues dans les centres d'avortement des provinces du Gauteng, du Mpumalanga et du Cap-Occidental. Des entretiens ont été réalisés à Soweto et au Cap avec 20 médecins de santé publique, des infirmières, un travailleur social et des directeurs de centres, et au Cap avec quatre responsables provinciaux. Bien que l'avortement médicamenteux ne soit pas encore proposé, 21% des femmes interrogées pouvaient y prétendre (huitième semaine de grossesse ou moins). L'accès aux centres de santé, y compris ceux pour l'avortement, était satisfaisant pour les femmes urbaines, mais plus limité pour les rurales. Il était également plus onéreux pour les femmes rurales de se rendre dans un centre. La plupart des femmes pensaient que l'avortement médicamenteux était acceptable et auraient voulu l'essayer, s'il avait été disponible. Les décideurs et les praticiens les soutenaient, car ils pensaient que l'avortement médicamenteux pouvait alléger la charge des services actuels. Il faut étudier comment élargir l'accès aux services d'avortement dans les zones rurales.

Resumen

El aborto con medicamentos es seguro y eficaz. En 2001 fue aprobado para la interrupción temprana del embarazo en Sudáfrica, donde el Departamento de Salud está pensando realizar su lanzamiento en el sector de salud pública. Nunca antes se habían descrito las actitudes de las mujeres y de los prestadores de servicios de salud hacia el aborto con medicamentos. Se recolectaron datos por medio de una encuesta cuantitativa entre 673 mujeres que recibieron servicios de aborto en las provincias de Gauteng, Mpumalanga y el Cabo Occidental. En Soweto y Ciudad Cabo se realizaron entrevistas a profundidad con 20 médicos, enfermeras, una trabajadora social y gerentes de salud pública, y en Cape Town con cuatro formuladores de políticas provinciales. Aunque aún no se estaba ofreciendo el aborto con medicamentos, el 21% de las mujeres entrevistadas eran elegibles para éste, ya que tenían una gestación de ocho semanas o menos. El acceso a los establecimientos de salud era razonable para las mujeres urbanas pero más limitado para las rurales, quienes incurrieron en mayores gastos de viaje para llegar a ellos. El aborto con medicamentos fue aceptado por la mayoría de las mujeres, quienes habrían estado dispuestas a intentarlo si hubiera estado disponible. Los formuladores de políticas y los proveedores brindaron su apoyo, ya que creían que el aborto con medicamentos podría aliviar la carga de los servicios actuales. Se debe pensar en cómo ampliar el acceso a los servicios de aborto en las zonas rurales.

Medical abortion (sometimes referred to as medication abortion), using a regimen of mifepristone and misoprostol has been shown to be a safe, effective and acceptable alternative to surgical abortion in many countries.Citation1Citation2Citation3

In South Africa, the 1996 Choice on Termination of Pregnancy (CTOP) Act and its amendments in 2004 are ground-breaking in their intention to provide better access to free abortion services, particularly for poor black women. The law allows for termination on request for pregnancies of 12 weeks or less, provided by a certified nurse practitioner or doctor. Pregnancies of 13-20 weeks may be terminated by a doctor when continuation of the pregnancy poses a risk to the woman's social, economic or psychological well-being.Citation4 The National Department of HealthCitation5 designates all abortion facilities in South Africa. However, the provision of abortion services has been restricted by a lack of facilities and shortages of trained health care providers providing abortions.Citation6 As a result, abortion services are overstretched.

First trimester abortion is provided at primary care level mainly by nurse practitioners. Second trimester abortion is provided at secondary and tertiary levels by physicians. Medical abortion could theoretically be offered by certified nurses in primary care clinics provided that emergency backup services are available for any complications. Nurses at primary care level could also provide surgical abortion backup using manual vacuum aspiration (MVA) in the small number of medical abortions that fail.

Providing medical abortion as an alternative to surgical services has a number of advantages. Some women may prefer medical to surgical abortion to avoid instrumentation of the uterus. Medical abortion could also potentially increase access in settings where providers are reluctant to provide surgical abortion services. Health care workers may be less opposed to a method of abortion that they do not have to initiate. Medical methods may require less staff input. Provision of medical abortion could increase women's options and broaden access to abortion services.Citation3Citation7

Medical abortion with 200mg mifepristone orally and 800mcg misoprostol vaginally may be used up to nine weeks of pregnancy at home or in the clinic in the first trimester, and using a different regimen, at the clinic in the second trimester of pregnancy.Citation7 In 2001 the South African Medicines Control Council approved a regimen of 600mg mifepristone and 400mcg misoprostol orally for medical abortions up to eight weeks of pregnancy. This drug regimen is not available at pharmacies but has been increasingly provided by designated private sector physicans and NGOs since 2002. However, data on provision and use is not yet available (Margaret Hoffman, Mediteam Trust, personal communication, 17 August 2005).

The National Department of Health is considering the introduction of medical abortion in the public health sector and the CTOP Amendment Bill of 2003 included medical abortion provision.Citation7 There have been concerns that women attend abortion services too late in their pregnancies to qualify for early medical abortion and that having to return for repeat visits may dissuade them from choosing the medical option. Further, ultrasound may be needed to determine the length of pregnancy, and the high cost of a 600mg dose of mifepristone, the dosage that was approved,Footnote* are additional concerns in a low-resource setting like South Africa.

The attitudes of women seeking abortion and of health care providers towards medical abortion have not previously been described. This paper reports on research that evaluated whether a significant proportion of women seeking abortion in public sector services would be early enough in pregnancy to be eligible for medical abortion. We also investigated the hypothetical acceptability of medical abortion among women, policymakers and providers and whether women would attend for follow-up. The results on the accuracy of clinician assessment of length of pregnancy without ultrasound, which was also part of the study, will be reported elsewhere.

Methods

Between November 2001 and March 2002, a prospective cross-sectional survey was conducted among women attending a convenience sample of abortion services at eight facilities in three provinces in South Africa. These were Chiawelo, a primary health care facility in urban Soweto, Gauteng; two primary health care services, two secondary hospitals and two tertiary care hospitals in urban Cape Town in the Western Cape; and Philadelphia Hospital, a secondary hospital serving a primarily rural population in Mpumalanga. They are the main facilities providing first trimester abortion in these geographical areas. In the Western Cape, additional secondary and tertiary hospitals were included where women obtain first trimester abortions and where a fuller perspective of health care providers' attitudes and the availability of emergency obstetric care could be obtained. All facilities serve a predominantly low socio-economic population and were similar in the type of services and counselling provided. All have facilities on site or nearby that can deal with any emergency or complication that arises.

In each facility, trained interviewers conducted face-to-face interviews lasting 20-30 minutes with women attending abortion services, using a standardised questionnaire in the woman's home language. Women were interviewed while waiting for care and therefore did not lose their places in the queue. Information collected included demographic characteristics such as age, intimate partner status, education, employment and geographical location in relation to the facility; and reproductive history such as parity, gravidity and prior contraceptive use. Information on seeking abortion was also collected, including time from knowledge of pregnancy to first contact with the health service and details of the woman's decision to have an abortion. Participants were given a description of medical abortion and were asked about their attitudes towards and their perceived willingness to have a medical abortion. They were not offered and did not use the method. All women had an ultrasound examination. With the exception of one of the tertiary facilities in Cape Town (n=239) and Philadelphia Hospital, the women also had a clinical examination to determine the length of their pregnancy. This was in order to compare the women's and clinicians' estimates to the ultrasound measurements.

Women attending for first trimester abortion were asked if they were interested in participating in a study on attitudes towards medical abortion. Most women who participated had come to schedule an abortion and may have visited a facility earlier to have their pregnancy confirmed. Data from 673 women were included. In Soweto, all women (n=272) who were approached to join the study agreed but due to time constraints only, 36% of all those presenting for first trimester abortion were interviewed. In Cape Town, 328 women were approached and 287 agreed and were included. There were 29 (10%) refusals and 12 (4%) were excluded post-interview either because the ultrasound showed they were not pregnant or due to insufficient data. At Philadelphia Hospital, all women (n=114) approached agreed to an interview.

Twenty individual in-depth interviews (four in Soweto, 16 in Cape Town) were conducted with public health service providers, equally divided between doctors and nurses performing and not performing abortions, a social worker and facility managers. In Cape Town, in-depth interviews were conducted with four provincial policymakers. Their views on the delivery of abortion services and medical abortion were recorded. Interviews were tape-recorded, transcribed and translated where necessary.

Written informed consent was obtained from all participants. Data were kept confidential and only a study identification number was used. Institutional ethical approval was obtained from the ethics review committees of the Population Council, the University of the Witwatersrand, the University of Cape Town and Mpumalanga Province.

For quantitative data, percentages were calculated for categorical variables, and means for continuous variables. Bivariate analysis was conducted to examine associations between selected variables of interest. We used a grounded theory approach to analyse the qualitative data.

Results

Demographic characteristics

The mean age of women attending the abortion services was 25 years (range 15-44). Just over half (55%) had a regular partner, but were not living with that partner. Thirty-two per cent had completed high school. Approximately 10% had tertiary education. Forty-one per cent were unemployed.

At the Philadelphia rural site, 31% were teenagers compared with 18% in the urban sites. A higher percentage of rural women did not live with their regular partner (67%). They were more likely to report being a student or scholar (40%) than women at the urban sites (24%). Women in Cape Town (24%) had the lowest rates of unemployment (Soweto 50%, Philadelphia 33%) and were more likely to report being employed full-time (30%) than women in the other sites (Soweto 3%, Philadelphia 4%), and had higher levels of tertiary education (18% vs. 8%).

Reproductive history

Almost all the women in the study (95%) said they knew the date of their last menstrual period (LMP). Just over half (51%) reported knowing when they were likely to have become pregnant although this figure varied considerably by site (Soweto and Cape Town 27%, Mpumalanga 51%). A minority, the same proportion in all sites (36%), reported knowing the exact date they were likely to have become pregnant.

One third reported that they had one living child. This figure was slightly higher among rural women (43%) than in Cape Town (30%). Almost the same percentage (32%) reported no living children, and 21% reported two living children.

The majority of women across all sites reported contraceptive use at some time in their lives (84%). Of these, 65% reported ever-use of injectable contraceptives. One third (31%) had ever used oral contraceptive pills, and one quarter (26%) had ever used condoms. A lower proportion of rural women (75%) reported ever-use of contraceptives. Very few rural women (1%) reported ever-use of condoms in contrast to almost 40% in Cape Town and 21% in Soweto.

Overall, 35% of participants had heard of emergency contraception. Only 8% of women at Philadelphia knew about emergency contraception, compared to 52% in Cape Town and 27% in Soweto. Of these, 24% had used it. Women with high school education were more likely to have heard of emergency contraception (37%) compared with 8% of those with primary or no schooling, but the trend did not continue for those with tertiary education. Only 6% of all the women reported a previous termination of pregnancy.

Thirty-six per cent of women reported having been using a contraceptive method when they conceived. A majority (54%) in the rural site reported using a method compared to 28% in the urban areas. Of those reporting contraceptive use, 54% reported using an injectable contraceptive. The largest proportion reported contraceptive failure while using the oral contraceptive pill (54%), followed by condoms at the urban sites (11%) and injectable contraception (26%) at the rural site. The most common reason (36%) for all method failure was that they forgot or chose not to use the method or used it inconsistently.

Abortion seeking and access to services

Seventy-six per cent of women reported that more than one week elapsed between the time they knew they were pregnant and seeking advice about an abortion. Of these, 46% said they waited because they were not sure they were pregnant, 10% because they were undecided about having an abortion, 11% due to partner or family opposition and 7% for financial reasons. Financial concerns were the second most common (20%) reason for delaying for rural women. Four times the proportion of rural women (13%) compared to urban women (3%) delayed seeking an abortion due to insufficient information on abortion and abortion services. Twenty-one per cent did not discuss their decision to have an abortion with anyone; 33% talked with a husband, boyfriend or partner, and 25% with a family member.

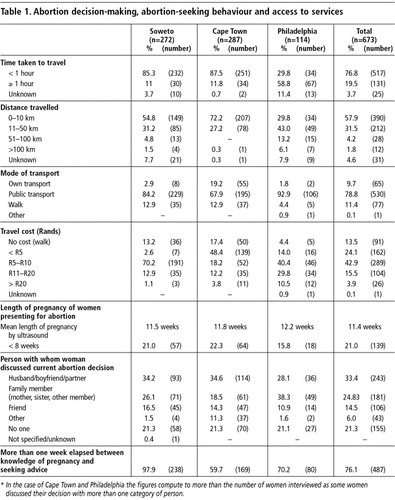

As shown in Table 1, most women (58%) and especially urban women (64%) travelled ≤10 km to reach health facilities. Travel distances were longer for rural women: 66% travelled >10 km and 16% travelled >50 km to reach the facility. Most women (79%) used public transport to reach the clinic, with the majority (77%) reaching the clinic in <1 hour. While access was good for urban women (86% travelling <1 hour), the majority of rural women (59%) travelled for >1 hour. Eighty-one per cent of women spent ≤10 Rands (approximately US$1.25) to reach the clinic. Rural women paid substantially more for transport.

In Cape Town and Philadelphia, 45% and 24% of women respectively had their abortions within a week of first contact with a health facility and the majority (86% in Cape Town, 91% in Philadelphia) within four weeks. The data for Soweto were not comparable, as on analysis it was clear that the question was understood differently.

Using ultrasound examination, the average duration of pregnancy was approximately 11 weeks, with rural women presenting slightly later. Twenty-one per cent of women presented at ≤8 weeks of pregnancy (the cut-off for medical abortion eligibility based on the MCC-approved label for mifepristone), with a slightly lower proportion of rural women (16%).

Women's opinions of medical abortion

Women overwhelmingly supported the theoretical notion of medical abortion. A greater proportion of urban women (98% in Soweto, 74% in Cape Town) reported interest in trying medical abortion than rural women (67%). Eighty-six per cent of the women who were eligible for medical abortion based on the length of their pregnancy expressed interest.

Attitudes of service providers, managers and policymakers towards medical abortion

Many service providers and policymakers raised general issues around barriers to accessing abortion services. These included there being too few facilities offering abortion, lack of sufficient staff to provide services, lack of theatre time or facilities available, lack of support and/or incentives for staff doing abortions, negative attitudes on the part of other health centre staff, inadequate referrals to abortion services at first contact and problems of confidentiality within the health care system. Service providers and policymakers also cited barriers such as lack of knowledge of the law, lack of information on where to access services, lack of knowledge about signs and symptoms of pregnancy, social stigma associated with abortion and negative attitudes towards abortion on the part of families, communities and service providers.

Policymakers and providers expressed generally favourable attitudes toward medical abortion. They felt it could offer an additional abortion method, and that some women would find the less invasive procedure and their ability to control the process appealing. They also thought it might place less of a load on health service personnel and be easier from a conscience point of view.

“Well, it is so much simpler.. women can get the pills and take it at home and everything is finished. She does not need to keep on coming back, it is more private... you do not [need] to have any invasive procedure, absolutely, if I had a choice, if I was in need of that, I would go for it. It is also much simpler on the provision of the service because people do not have to initiate anything because the woman takes the pills herself. The onus is on her. She must answer to God, if that is her view, for what she is doing, not the service provider.” (Policymaker)

“…if medical termination of pregnancy can be made to be successful it actually decreases the workload on the staff. That reduces the stress… and makes people more willing to help, I think... if there are fewer evacuations of uteri… we will also be able to reduce things like blood transfusion requirements, hopefully reducing the number of complications from cases like perforated uteri. You should be able to [choose] a less invasive procedure... also the idea of encouraging people to present early.” (Health care provider)

Discussion

Women in the study seeking an abortion were younger (47% under 25 years) than the general female population (30% under 25 years) of reproductive age.Citation8 The higher educational status of women attending abortion services than in the general population (24%)Citation8 may indicate that more educated and younger women have better knowledge of the law and access to services or are more likely to seek an abortion with an unintended pregnancy. Better educated women in developing countries may exercise reproductive choices more successfully. Improved employment opportunities can create more favourable perceptions of their life chances, leading to greater incentives to delay childbearing.Citation9Citation10

Women in South Africa experience high rates of teenage and unintended pregnancy, with 35% reporting pregnancies by age 19, and 56% unplanned or unwanted pregnancies.Citation8 The high proportion of teenagers in this study seeking abortion and the data on non-use or ineffective use of contraception provides opportunities for interventions on several levels. Similar to other South African studies,Citation11Citation12 awareness of emergency contraception appeared to be higher in the cities, while very few rural women seeking abortion knew about emergency contraception. There is an urgent need to promote awareness of emergency contraception, both in a general sense, and as part of contraceptive and post-abortion counselling in order to reduce the high rates of unintended pregnancy.

Given the escalating HIV epidemic in South Africa, with a public sector antenatal prevalence of 29% in 2004 and approximately 20% of the population living with HIV,Citation13 the low reported condom use is alarming and underscores the need for urgent and vigorous promotion of dual protection for young women who wish to avoid pregnancy and yet are at risk of STI and HIV infection from unprotected intercourse.

There is a general perception that women attend abortion services late in pregnancy, i.e. after 12 weeks of pregnancy. In this study, a fifth of women came to the clinic at ≤8 weeks of pregnancy. This indicates that a significant proportion of women would potentially be eligible for early medical abortion.

Legal provisions making access to safe abortion easier since 1997 are generally having a positive impact on urban women's lives. However, this study has confirmed that rural women face more barriers in accessing health facilities, impeding access to abortion. Rural women delayed contacting a health facility to confirm their pregnancy, often travelled a long distance to health facilities and incurred high costs in reaching a facility to schedule their abortion, and needed to return subsequently for the abortion itself. Despite public sector health care being free, transport costs to reach facilities for rural women are prohibitive.

These factors could also impact on access to medical abortion. Although medical abortion could be initiated immediately upon the woman reaching a facility, two clinic visits are required, one for counselling and provision of the medications and another approximately two weeks later for confirmation of complete abortion.

The higher educational and employment levels of women in Cape Town may reflect easier access to information and services for them; there is likely a need for more information for other women. Rural women were more likely to have inadequate information about abortion services. Poorer health service access for rural women is systemic and not confined to medical abortion or abortion access. A general strengthening of health services is therefore needed, to ensure that rural women have better access to contraceptive information and reproductive health services.

The findings highlight the continued stigma of abortion, evidenced by the fact that almost a quarter of women did not discuss their decision to have an abortion with anyone else. It is of concern that many women with unintended pregnancies have less than adequate social support. South Africa is the only country to have passed a new and progressive law on abortion since the ICPD that explicitly allows women to obtain legal and safe abortion in terms of their individual beliefs.Citation14 Nevertheless, discrimination and stigmatisation of women seeking abortion is indicative of the inequitable gender burden borne by women in a society that remains deeply patriarchal and impedes abortion access.

Although abortion is legal, the low percentage of women reporting a previous abortion should be treated with caution. It is likely to be an underestimate, as women may have felt uncomfortable disclosing a previous abortion, anticipating negative reactions from providers.

There are a number of limitations to this study. Firstly, the use of a convenience sample of facilities means that this data may not be representative of all abortion services or women seeking abortion. Therefore the results may not be generalisable to other services in the country. However, both rural and urban facilities were included, as were facilities offering different levels of care in three provinces, providing abortion for the full range of pregnancy lengths. This provides some confidence in the reliability of the data. Secondly, women in this study did not receive medical abortion. While women and health care providers expressed a strong interest in medical abortion being provided in public sector services, conclusions cannot be drawn from this research about what will happen with actual use. Finally, although we used standardised data collection instruments and a common protocol at all sites, we cannot rule out differences in the administration of the instruments or interpretation of the questions that might have an impact on the data.

Conclusion

This study provides additional information on the factors impeding access to abortion services and contraception for a population of South African women. In addition, the study lays to rest a number of concerns regarding medical abortion and its appropriateness for introduction in the public health sector in low resource settings, adding to the evidence base for informed decisions to be made. Now that the World Health Organization has included a regimen of 200mg mifepristone plus 800mcg of misoprostol on the Essential Medicines List,Citation15 the dose of 600mg of mifepristone approved by the Medicines Control Council in 2002 needs to be lowered to 200mg, as it is a primary factor in the cost-effectiveness of medical abortion. Provision by well-trained certified nurses at primary health care level, as is common practice anyway in South Africa for first trimester surgical abortion, can make it an affordable additional abortion option in the public health sector.Citation16

The finding that a reasonably large group of women could potentially use medical abortion through public sector abortion services is contrary to the belief that South African women do not attend services early enough to benefit from this method. Medical abortion would therefore increase women's abortion options and possibly improve access to abortion services. Further operations research has been completed to gauge actual use, the convenience and safety of home or clinic use of misoprostol, the feasibility of medical abortion in the absence of ultrasound facilities, the need for and access to emergency services and the success of follow-up of women.Citation17 Telephonic follow-up may be possible in urban areas and even some rural areas, where cell-phone ownership is common. A telephone help line, similar to that initiated in the Western Cape with respect to emergency contraception, could assist women if they became worried or had questions while going through the abortion process at home.

Promoting new methods for termination of pregnancy in South Africa and hence improving access to reproductive choice for women is particularly important in a global context in which reproductive rights and social justice are potentially being eroded by conservative policies.Citation18

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by grants from the Population Council. We are indebted to our clinical colleagues at hospitals, clinics and health centres in Gauteng, the Western Cape and Mpumalanga for their co-operation and support. We would also like to acknowledge the fieldworkers and the participants for their contributions.

Notes

* A dosage of 200mg mifepristone has, since that approval was given, been shown to be equally effective.Citation7

References

- DA Grimes. Medical abortion in early pregnancy: a review of the evidence. Obstetrics and Gynecology. 89(5 Pt 1): 1997; 790–796.

- WHO Task Force on Post-Ovulatory Methods of Fertility Regulation. Menstrual regulation by mifepristone plus prostaglandin: results from a multicentre trial. Human Reproduction. 10(2): 1995; 308–314.

- B Winikoff, I Sivin, KJ Coyaji. Safety, efficacy, and acceptability of medical abortion in China, Cuba, and India: a comparison trial of mifepristone-misoprostol versus surgical abortion. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 176(2): 1997; 431–437.

- D Cooper, C Morroni, P Orner. Ten years of democracy in South Africa: documenting transformation in reproductive health policy and status. Reproductive Health Matters. 24(12): 2004; 70–85.

- Republic of South Africa. The Choice on Termination of Pregnancy Amendment Bill, 2003. Government Gazette Notice No. 1388 of 2003, 19 May 2003. At: <http://www.info.gov.za/gazette/bills/2003/24869b.pdf. >. Accessed 6 August 2005.

- KE Dickson, RK Jewkes, H Brown. Abortion service provision in South Africa three years after liberalisation of the law. Studies in Family Planning. 34(4): 2003; 277–284.

- World Health Organization. Safe Abortion: Technical and Policy Guidelines for Health Systems. 2003; WHO: Geneva.

- Department of Health, Republic of South Africa. South African Demographic and Health Survey. 2001; Department of Health: Pretoria.

- B Klugman. Balancing means and ends: population policy in South Africa. Reproductive Health Matters. 1: 1993; 44–57.

- M Mamadani, P Garner, RP Harpham. Review article. Fertility and contraceptive use in poor urban areas of developing countries. Health Policy and Planning. 14: 1993; 199–209.

- I Siebert, PS Steyn. Knowledge and use of emergency contraception in a tertiary referral unit in a developing country. European Journal of Contraception and Reproductive Health Care. 7: 2002; 137–143.

- J Smit, L McFadyen, M Beksinska. Emergency contraception in South Africa: knowledge, attitudes and use among public sector primary health care clients. Contraception. 64: 2001; 333–337.

- Department of Health, Republic of South Africa. Summary Report. 2005; National HIV and Syphilis Antenatal Seroprevalence Survey in South Africa: Pretoria.

- L Hessini. Global progress in abortion advocacy and policy: an assessment of the decade since ICPD. Reproductive Health Matters. 13(25): 2005; 88–100.

- WHO Essential Medicines Library. At: <http://mednet3.who.int/EMLib/DiseaseTreatments/MedicineDetails.aspx?MedIDName=443@mifepristone-misoprostol. >. Accessed August 2005.

- Cullingworth L, de Pinho H. Cost analysis of service provision of medical abortions in the public health sector at primary and secondary level. Monograph. University of Cape Town. June. 2002.

- Kawonga M, Blanchard K, Cooper D, et al. Integrating medical abortion into safe abortion services in South Africa. Presentation at Eleventh Reproductive Health Priorities Conference, Sun City, Fourways, South Africa. October. 2004.

- S Correa, A Germain, RP Petchesky. Thinking beyond ICPD+10: Where should our movement be going? [Roundtable]. Reproductive Health Matters. 13(25): 2005; 109–119.