Abstract

In Turkey, there is an unmet need for induced abortion services provided by the public health services, especially in rural and semi-urban areas. The objective of this clinical study was to show that early medical abortion could be introduced safely in Turkey to improve women's access to services. In the study, women aged 18-49 up to 56 days of pregnancy were offered a choice between medical abortion with 200mg mifepristone followed by 400mcg oral misoprostol and MVA with local anaesthesia. 209 chose medical and 149 surgical abortion. Data from an additional 112 women were collected to obtain a similar number of surgical abortion cases. Women's preference for and satisfaction with the chosen method, side effects and complications up to the 14-day follow-up visit were recorded. 75% of women who chose medical abortion opted for home use of misoprostol. Pain with medical abortion on average lasted 3.6 ± 3.0 days and with surgical abortion 3.7 ± 2.9 days. 90% of women who had medical abortion said they would prefer it again compared to 70% of those having surgical abortion. There were 1.4% ongoing pregnancies in the medical abortion group and none in the surgical group. Provider training and familiarity with medical abortion are crucial. The high incomplete abortion rate indicates that the dose and regimen of misoprostol should be reconsidered. The findings support the introduction of early medical abortion in Turkey.

Résumé

La Turquie connaît un besoin insatisfait de services d'avortement dans le système de santé publique, particulièrement dans les zones rurales et semi-urbaines. L'objectif de cette étude clinique était de montrer que l'avortement médicamenteux précoce pouvait être introduit sans risque en Turquie pour améliorer l'accès à ces services. L'étude a proposé à des femmes âgées de 18 à 49 ans, jusqu'à 56 jours de grossesse, le choix entre un avortement médicamenteux avec 200mg de mifépristone suivi de 400mcg de misoprostol oral, et un avortement chirurgical par aspiration manuelle avec anesthésie locale. 209 ont choisi l'avortement médicamenteux et 149 l'avortement chirurgical. Des données ont été recueillies auprès de 112 autres femmes afin d'obtenir un nombre similaire d'avortements chirurgicaux. L'étude a enregistré la préférence des femmes et leur satisfaction avec la méthode choisie, les effets secondaires et les complications jusqu'à la visite de suivi 14 jours après. 75% des femmes ayant choisi l'avortement médicamenteux ont pris du misoprostol à domicile. Les douleurs après l'avortement médicamenteux ont duré en moyenne 3,6 ± 3,0 jours et 3,7 ± 2,9 jours après l'avortement chirurgical. 90% des femmes ayant choisi l'avortement médicamenteux ont affirmé qu'elles préféreraient à nouveau cette méthode contre 70% pour l'avortement chirurgical. Les avortements médicamenteux ont abouti à 1,4% de poursuite de grossesse, contre aucune pour les avortements chirurgicaux. Il est essentiel de former les praticiens et de les familiariser avec l'avortement médicamenteux. Le taux élevé d'avortements incomplets indique que la posologie du misoprostol devrait être révisée. Les conclusions soutiennent l'introduction de l'avortement médicamenteux précoce en Turquie.

Resumen

En Turquía, existe la necesidad insatisfecha de servicios de aborto inducido prestados por el sector salud pública, especialmente en las zonas rurales y semiurbanas. El objetivo de este estudio clínico fue mostrar que en Turquía podría lograrse el lanzamiento seguro del aborto con medicamentos temprano para mejorar el acceso a los servicios. En el estudio, a mujeres de 18 a 49 años de edad, con embarazos de hasta 56 días, se les ofreció escoger entre el aborto con medicamentos - usando 200 mg de mifepristona, seguida de 400 mcg de misoprostol vía oral - y la AMEU con anestesia local; 209 escogieron el aborto con medicamentos y 149 el quirúrgico. Se recolectaron datos de otras 112 mujeres para obtener un número similar de casos de aborto quirúrgico. Se registró la preferencia de las mujeres por el método escogido y su satisfacción con éste, los efectos secundarios y las complicaciones hasta la visita de seguimiento 14 días después. El 75% de las mujeres que eligió el aborto con medicamentos optó por usar el misoprostol en el hogar. El dolor durante el aborto con medicamentos duró en promedio 3.6 ± 3.0 días; con el aborto quirúrgico, 3.7 ± 2.9 días. El 90% de las mujeres que tuvieron un aborto con medicamentos dijo que lo preferiría de nuevo, comparado con el 70% de aquéllas que tuvieron un aborto quirúrgico. Hubo 1.4% de embarazos continuados en el grupo de aborto con medicamentos, ninguno en el de abortos quirúrgicos. Es fundamental capacitar a los proveedores y familiarizarlos con el aborto con medicamentos. Debido a la alta tasa de aborto incompleto, debe reconsiderarse la dosis y el régimen de misoprostol. Los resultados apoyan el lanzamiento del aborto con medicamentos temprano en Turquía.

Abortion has been legal on request in Turkey up to ten weeks of pregnancy since 1983, under a law that also authorised general practitioners to terminate pregnancies.Citation1 However, there is still an unmet need for induced abortion services provided by the public health services, especially in rural and semi-urban parts of the country.Citation2Citation3Citation4

According to the 2003 Turkish Demographic and Health Survey (DHS), 24% of ever-married women in Turkey have had an induced abortion, of whom some 58% have had only one abortion. The abortion ratio in 2003 was 11.3 abortions per 100 pregnancies, down from 14.5 in 1998 and 18.0 in 1993.Citation3Citation4Citation5 The percentage of women using contraception in 2003 was 71%, of which 42.5% were using a modern method and 28.5% a traditional method. Overall, 73% of abortions were carried out in the first month of pregnancy and 22% in the second month; only 5% were performed in the third month or later.Citation4 78% of those who had had an induced abortion reported that it took place at a private physician's office (57%) or a private hospital or clinic (21%), which implies that the public health services are meeting only 22% of the demand for induced abortion. Rural women were more likely than urban women to have had their abortions privately.Citation3Citation4Citation5

The reasons usually given by public institutions for performing relatively fewer abortions are the high caseload of other obstetric and gynaecological cases and lack of time available for surgical abortions. However, abortions performed privately are much more costly,Citation3Citation5 and the coverage of abortion services in the public sector needs to be increased.

Several efforts have already been made in this direction. Specifically, a study was carried out in Turkey with the collaboration of the Special Programme of Research, Development and Research Training in Human Reproduction at WHO to demonstrate that general practitioners (GPs) can be trained to terminate pregnancy using manual vacuum aspiration (MVA). Based on the favourable results of that study, MVA was introduced in the country and GPs were authorised to do early abortions using MVA. As a result, access to services was expanded.Citation6Citation7Citation8Citation9 However, many public hospitals are still not providing abortion services at all or only for pregnancies up to eight weeks, which creates barriers for women.Citation3Citation4Citation5Citation7Citation10

According to the Turkish national guidelines on abortion, first prepared in 1996 and updated in 2002, dilatation and curettage (D&C), electric vacuum aspiration and MVA are the surgical methods that should be used for induced abortions in Turkey. Most public and private clinics still prefer to use general anaesthesia during these procedures, even though it is not recommended in the Guidelines.Citation11

According to the most recent study on the causes of maternal deaths in Turkey, in 1997-98, it was found that despite its legality, induced abortion is still a cause of maternal deaths, indicating that abortion services need improving in terms of quality and coverage.Citation12

Evidence has been accumulating internationally that medical abortion is a safe and appropriate alternative to surgical abortion methods, including in developing countries where resources are limited. Medical abortion is easy, simple, safe and effective for ending pregnancy and rarely requires the involvement of obstetrician-gynaecologists. In most studies, the rate of complete abortions is 95% or more.Citation3Citation13Citation14Citation15Citation16Citation17Citation18Citation19Citation20Citation21 Thus, medical abortion could play an important role in reducing the unmet need for services in Turkey and improve women's access to abortion.

The first attempt to introduce medical abortion in Turkey was in the early 1990s. However, mifepristone had not yet been officially approved, so the application was refused by the Commission at the Ministry of Health (MoH) that supervises and decides on which new methods of fertility regulation are introduced into the country. In 1994, approval of mifepristone was obtained, and the Commission then advised that it was possible to carry out an introductory study on medical abortion using mifepristone and misoprostol.Citation22

Based on this approval, a study was designed to gather data on medical abortion, supported by the Population Council, in terms of the efficacy of 200mg mifepristone with 400mcg oral misoprostol for terminating pregnancy up to 56 days LMP. At the same time as our study, a similar regimen was used in Tunisia, where they have had relatively long experience with medical abortion, including clinical studies, since 1996.Citation17 We planned to follow a similar protocol. In the study, we also wanted to find out where women preferred taking the misoprostol, whether in the clinic or at home. At the same time, the study looked at women's preference for a medical vs. a surgical method, any side effects and complications, and satisfaction levels with the method chosen. The aim was to add to existing evidence that medical abortion is a suitable option for early abortion, and to convince policymakers and health service providers, including some obstetrician-gynaecologists who were not convinced, that it should be introduced in Turkey.

Methodology

This was a clinical study that took place in 2000 in two university obstetrics-gynaecology clinics, one in Ankara and one in Eskişehir, one state maternity hospital in Azmir and one government-sponsored Maternal and Child Health/Family Planning Centre in Ankara. Five physicians in these clinics who were already providing surgical abortion services were trained in the management of medical abortion. This was the first exposure to medical abortion for all the providers in the study.

In the training programme, the study protocol, record forms, eligibility criteria for recruitment, case management, home record cards and management during follow-up were covered. An instruction book with this same information was also given out. Throughout the study all clinical sites were visited and monitored periodically by the coordination team from Hacettepe University Public Health Department.

This was a descriptive study whose aim was to find out whether, if offered a choice between medical abortion and MVA with local anaesthesia, a substantial proportion of Turkish women would choose medical abortion and have comparably good outcomes. In the study, similar inclusion criteria were used, similar information collected and similar follow-up visits scheduled for both medical and surgical abortion cases. All consenting women between the ages of 18 and 49 were enrolled over an eight-month period if they had an intrauterine pregnancy up to 56 days LMP, lived or worked within one hour of the study site, were willing to return for at least one follow-up visit and had no known allergies to mifepristone or misoprostol. Length of pregnancy was assessed using one or more standard methods, including physical examination, menstrual history, ultrasound and a beta-hCG pregnancy test. Use of ultrasound was not required in the study protocol, but most providers chose to use it for two reasons. First, use of ultrasound was routine practice for them for most abortion cases, and second, as medical abortion was new to them they tended to be cautious, to be on the safe side.

Women who chose medical abortion took 200mg mifepristone orally in the clinic. They were then given the choice of taking the 400mcg oral misoprostol two days later, either in the clinic or at home. The first 20 women enrolled at each site were supposed to be asked to take the misoprostol in the clinic, so as to give providers some familiarity with the abortion process with the method. However, this instruction was not followed at all sites; most of the providers said they were convinced about the safety of home use of misoprostol after very few cases.

Women selecting home use were given two 200mcg tablets of misoprostol as well as analgesic medication in case of pain, to take at home. They were instructed to take the misoprostol orally two days after the mifepristone and to take the pain medication if needed. Women who opted to take the misoprostol at the clinic were given an appointment two days later and took the drug orally there. All women were given a home record card to record their experiences and symptoms, such as bleeding, pain and need for analgesic. All the women were asked to return to the clinic two weeks later for assessment of abortion status and evaluation of the home record cards.

For women who selected surgical abortion, manual vacuum aspiration was used under local anaesthesia. Similar case management and follow-up schedules were applied as with medical abortion cases, to record and treat complications and side effects.

Successful medical abortion cases were defined as complete abortions without recourse to surgical intervention at any point. Incomplete abortion was clinically determined to be any case requiring a surgical procedure to complete evacuation of the uterus. Ongoing pregnancies included all cases with two weeks of clinically estimated growth of the gestational sac during the study period.Citation22Citation23 Women with complete abortions were discharged from the study at the two-week follow-up visit. Women with incomplete abortion were offered the choice of waiting an additional week for the bleeding to stop or, if they did not wish to wait an additional week, completion was performed using MVA. Surgical completion was provided to all women with ongoing pregnancies.

A detailed report was writtenCitation22 and part of the data from the medical abortion arm of the study was published.Citation23

Findings

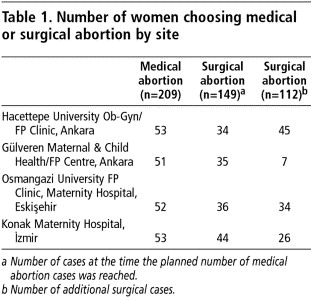

During the study period 1,533 women requested an abortion at the four study sites; 470 of them were eligible for the study and all 470 agreed to participate. Participants were aged 18 to 49 years old. When both medical and surgical methods were offered, 209 women chose medical abortion and 149 women opted for surgical abortion. The medical abortion pills provided for the study ran out at 209 women, as planned. After that, aspiration abortion was women's only option, but data from an additional 112 women who had a surgical abortion within the study criteria were recorded (Table 1).

The ages of the women who had medical or surgical abortion were similar as that was one of the matching criteria, but the educational level of women in the medical abortion group was significantly higher compared with the surgical group which might indicate that the educated group had some information on the method beforehand.Citation22 All women in both groups had pregnancies up to 56 days LMP.

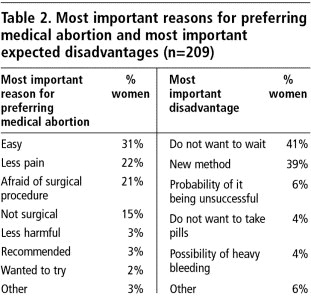

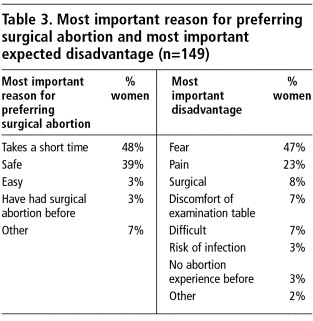

On the home record cards, filled out after the women had had their abortions, the women were asked to state the most important reason why they preferred the method they chose and the most important expected disadvantage of that method (Table 2). The most frequent reasons given for choosing medical abortion were either that it was easy or involved less pain or that they were afraid of the surgical procedure. The disadvantages they expected were having to wait for the abortion to happen and that it was a new method. The women who chose surgical abortion (Table 3) said they preferred it because it took a short time and was safe. Fear was the most common disadvantage of surgical abortion expected, followed by concern about pain.

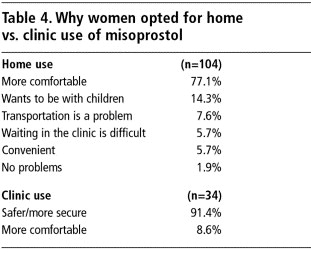

There were 69 women at the four sites who were required to take their misoprostol at the clinic. Of the remaining 138 who chose medical abortion (not including two for whom records were incomplete), 104 (75%) opted for home use and 34 (25%) opted for clinic use of the misoprostol. Table 4 details their reasons for choosing home vs. clinic use of misoprostol. Nine out of ten of those who opted for clinic use thought it would be safer whereas most of those who preferred home use thought it would be more comfortable.

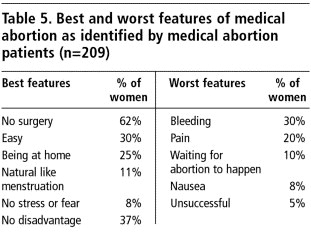

At the two-week follow up visit, women were asked to state the three best and worst features that they experienced with medical abortion. The most frequently mentioned best features were that there was no surgery involved, it was easy and they were at home during the abortion. The bleeding, the pain and waiting for the abortion to happen were the most frequent worst features of medical abortion noted by the women (Table 5).

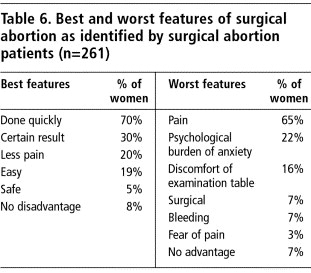

Similarly the best features of surgical abortion experienced were that it was quick, the result was certain and there was little pain. The most frequently stated worst features were having pain, psychological burden of anxiety and feeling uncomfortable in the lithotomy position on the examination table (Table 6).

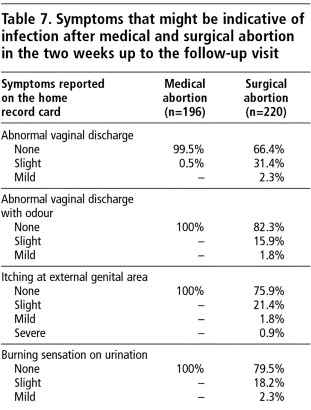

According to the home record cards, pain with medical abortion on average lasted 3.6 ± 3.0 days and with surgical abortion on average 3.7 ± 2.9 days.Citation22 Some other symptoms on the home record cards recorded in detail by 196 of the women who had a medical abortion and 220 of the women who had a surgical abortion are shown in Table 7.

No life-threatening event occurred in either group. Although the symptoms recorded on the follow-up record card are likely to have been subjective, they still give some clues as to possible side effects and complications. As seen in Table 7, all the symptoms that might be indicative of infection - abnormal vaginal discharge with odour, itching at external genital area and burning sensation on urination - were only reported by women having a surgical abortion.

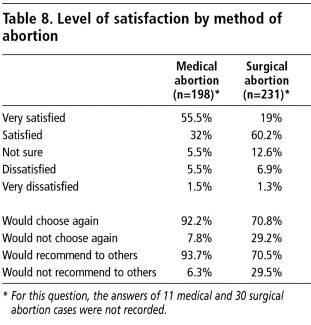

Although the great majority of women were either very satisfied or satisfied with both methods, far more women were very satisfied with medical than surgical abortion and far more would choose it again and recommend it to others (Table 8).

Overall, 7% of the women did not come for the follow-up visit (5.2% of the medical abortion group and 11.4% of the surgical abortion group). However, most of those who did not attend were followed up through phone calls.

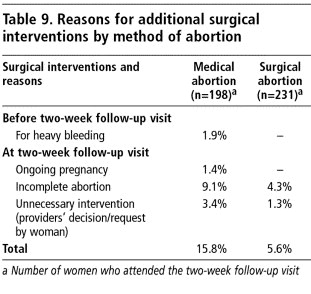

In the medical abortion group, surgical interventions were done at the two-week follow-up visit for cases of ongoing pregnancy (1.4%) or incomplete abortion (9.1%). Our data show that the failure rate for the women with 50-56 days LMP was not higher than among those with up to 49 days LMP (data not shown). For cases of heavy bleeding before the two-week follow-up visit, surgical abortion was performed as a medical indication (1.9%). However, there were also some unnecessary surgical interventions, especially in cases where there was some bleeding and the uterine cavity was checked with an instrument. This diminished the success rate. In other cases, it was because the woman did not want to wait another few days to see if the bleeding would stop, or due to any other signs like continuation of slight bleeding and/or abdominal pain which might be within expected limits in the abortion process (Table 9).

In the surgical abortion group, no ongoing pregnancy was observed. Additional surgical interventions were made at the two-week follow-up visit in cases of incomplete abortion, and several unnecessary surgical interventions were made due to provider's decision or at the woman's request (Table 9).

Discussion

This study demonstrates that a simplified medical abortion regimen can be safely offered in Turkey in hospital-based abortion clinics as well as at primary health care level in family planning clinics, which in turn could reduce the unmet need for induced abortion services.

The findings indicate that the level of side effects and complications with medical abortion are comparable to those with MVA and that medical abortion has some additional advantages over MVA. In addition, home use of misoprostol was preferred by the majority of the women having a medical abortion and did not cause any medical problems for them. Home use of misoprostol can therefore save both providers' time and one clinic visit for many women.

A limitation of the study was that when the planned number of medical abortion cases had been reached (209), the number of surgical cases had reached only 149. This indicates a high preference for medical abortion when both methods are offered at the same time. In order to reach similar numbers, 112 women could not be given a choice of method.

One of the most important lessons learned from this study was the significance of the training and familiarity of the providers with medical abortion. Observations during the study indicated that experienced and confident providers seemed to be an important factor in the provision of the method, especially for diminishing unnecessary surgical interventions for abortions perceived to be incomplete. It is likely that higher success rates will come with increasing provider and patient confidence in the medical method.Citation16Citation17

Surgical abortion has been provided for a long time in Turkey, and providers have sufficient case management experience. Despite the fact that all the providers had received training in the management of medical abortion, they were still cautious and there were a number of unnecessary surgical interventions. We believe that this can be reduced in future with increased training and experience and also through the use of a standard protocol that describes when and when not to intervene.

The other lesson was that the high rate of incomplete medical abortions needs further attention, and the regimen used in relation to length of pregnancy needs to be reconsidered. In fact, most evidence-based guidelines support a regimen of 200mg mifepristone followed by 400mcg misoprostol orally only up to 49 days of pregnancy LMP. Although in our study, the failure rate for the women at 50-56 days LMP was not higher than among those at up to 49 days LMP, this has been found with this regimen in other studies. The incomplete abortion rate could be reduced substantially by using an extra dose of misoprostol in the case of incomplete abortion or by using a regimen of 200mg mifepristone followed by 800mcg misoprostol vaginally 36-48 hours later.Citation15Citation18Citation24 Our proposals for future policy will be informed by this knowledge.

Providing medical abortion for the first time in a country poses challenges that are both clinical and attitudinal as well as strategic in nature. The strategies should be clear and appropriate for the country's health policy and health care system and should aim to contribute to improving the accessibility of abortion services in places where unmet need is greatest. During the introductory phase, decision-makers and medical professionals who know very little about medical abortion and those who may even oppose the method should be targeted to receive information. Women of reproductive age should also be priority recipients of information. Proper training of providers, including country-specific standard protocols for medical abortion are also very important for a successful medical abortion programme. All of these are being planned for Turkey.

The results of the study have been reported to the Ministry of Health for their consideration and a large information dissemination meeting was also held in Ankara in 2002. The audience included international and national participants, especially policymakers and people from the Ministry of Health, gynaecologists, physicians from family planning clinics and public health professionals based in universities, and extensive discussions took place. On the basis of the women's satisfaction with medical abortion and acceptability of the effects and side effects of the method in this study, which were encouraging, as well as what we have learned about improving both the drug dosage and regimen and provider training, we believe we should definitely move to introduce early medical abortion on a wider scale in Turkey.

As a follow-up to this study, we launched a further study in 2004 of home use vs. clinic use of misoprostol and oral vs. sublingual use of misoprostol, which at this writing (August 2005) is continuing. We hope after completion of this second study to develop guidelines for national use of medical abortion in Turkey. We hope other countries can benefit from our experience as well.

Acknowledgements

Our thanks to the women who participated in the study, to each of the local investigators at the four study sites and the Population Council for their support for the medical abortion arm of the study. Last but not least, the authors would like to thank Türküler Erdost (MSc, Social Psychology) for her valuable contribution.

References

- Population Planning Law, No.2827, published in the official gazette of 27 May 1983 No.18059. Ankara, Turkey.(Nüfus Planlaması Yasası # 2827, Resmi Gazete, 27 Mayıs 1983, sayı: 18059, Ankara, Turkiye).

- A Koseli. Women's health and reproductive health care within the framework of the 2003 Demographic and Health Survey of Turkey. Population Challenges, International Migration and Reproductive Health in Turkey and the European Union: Issues and Policy Implications. 2004; Turkish Family Health and Planning Foundation: Istanbul.

- A Akin, T Enunlu. Induced abortion in Turkey. A Akin. Contraception and Maternal Health Services in Turkey: Results of Further Analysis of 1998 Turkish DHS. 2002; Hacettepe University, TFHP Foundation and UNFPA: Ankara, 147–175.

- Hacettepe University, Institute of Population Studies, Ministry of Health, Mother and Child Health and Family Planning General Directorate, State Planning Organisation and European Union. Turkish Demographic and Health Survey 2003. Ankara, 2004.

- G Ergör, A Akin. Abortion in Turkey. A Akin, M Bertan. Contraception, Abortion and Maternal Health Services in Turkey. 1996; Ministry of Health (Turkey) and Macro International: Calverton MD, 91–113.

- BS Ozvaris, L Akin, A Akin. The role and influence of stakeholders and donors on reproductive health services in Turkey: a critical review. Reproductive Health Matters. 12(24): 2004; 116–127.

- D Huntington, AA Dervisoglu, JM Pile. The quality of abortion services in Turkey. International Journal of Gynecology and Obstetrics. 53: 1996; 41–44.

- WHO/HRP collaborative project to develop training methods for physicians to provide family planning and pregnancy terminations. Ankara: Hacettepe University Medical Faculty, Department of Public Health, 1982. (Unpublished report).

- Planning for the future of family planning in Turkey. 1992; Republic of Turkey Ministry of Health General Directorate, Mother and Child Health and Family Planning: Ankara.

- A Bulut. Abortion services in two public sector hospitals in Istanbul, Turkey: how well do they meet women's needs?. AI Mundigo, C Indriso. Abortion in the Developing World. 1999; Zed Books for WHO: London, 259–278.

- Republic of Turkey Ministry of Health General Directorate, MCH/FP. National Family Planning Service Guidebook (1): Family Planning and Reproductive Health. Ankara, 1996 (Updated 2002).

- A Akın, GB Doğan, S Mıhçıokur. Survey of the causes of maternal mortality from the hospital records in Turkey. 2000; Ministry of Health (Turkey), Hacettepe University Medical School Public Health Department, WHO and UNFPA: Ankara. Unpublished report.

- Medical abortion: meeting women's needs. J Hebden. An FPA Report in Conjunction with the Population Council. 1999; Newnorth Print: London.

- C Ellerston, B Elul, B Winikoff. Can women use medical abortion without medical supervision?. Reproductive Health Matters. 5(9): 1997; 149–161.

- World Health Organization. Safe Abortion: Technical and Policy Guidance for Health Systems. 2003; WHO: Geneva.

- B Elul, S Hajri, NN Ngoc. Can women in less-developed countries use a simplified medical abortion regimen?. Lancet. 357: 2001; 1402–1405.

- NT Ngoc, VQ Nhan, J Blum. Is home-based administration of prostaglandin safe and feasible for medical abortion? Results from a multi-site study in Vietnam. BJOG: An International Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology. 111(8): 2004; 814–819.

- World Health Organization. Comparison of two doses of mifepristone in combination with misoprostol for early medical abortion: a randomized trial. British Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology. 107: 2000; 524–530.

- S Hajri, J Blum, N Gueddana. Expanding medical abortion in Tunisia: women's experiences from a multi-site expansion study. Contraception. 70: 2004; 487–491.

- K Abuabara, S Blum. Providing Medical Abortion in Developing Countries - An Introductory Guidebook. 2004; Gynuity Health Projects: New York.

- CS Shannon, B Winikoff. Misoprostol, An Emerging Technology for Women's Health. Report of a Seminar. 2004; Population Council: New York.

- Kocoglu OG. Comparison of medical abortion by using mifepristone and misoprostol with surgical methods in terms of outcomes and side effects. Ankara: Hacettepe University Medical School Public Health Department, 2002. (Unpublished report) (Mifepriston ve Misoprostol ile yapılan Tıbbi Düşük yönteminin yan etki ve sonuçları yönünden Cerrahi Düşük yöntemi ile karşılaştırılması. Ankara: Hacettepe “niversitesi Tıp Fakültesi,Halk Sağlığı Anabilim Dalı, 2002).

- A Akin, J Blum, S Ozalp. Results and lessons learned from a small medical abortion clinical study in Turkey. Contraception. 70: 2004; 401–406.

- Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists. The Care of Women Requesting Induced Abortion. National Evidence-Based Clinical Guidelines. London: RCOG, September 2004.