Abstract

The clinical safety, efficacy and acceptability of mifepristone and misoprostol in the Indian context have been well studied, but little is known about how they are being used, who is using them, how women access them or how providers, chemists, women and their partners perceive medical abortion. This paper reports on part of a study on these issues, a survey of 209 chemists, in the Indian states of Bihar and Jharkhand in 2004. It found that only 34% of the interviewed chemists stocked mifepristone and misoprostol, sales volumes were low and there was more demand for cheaper, often ineffective preparations for abortion. Men were more likely to buy abortifacient drugs than women. Chemists knew mifepristone and misoprostol were prescription drugs but less about dosage and side effects. Most sales appeared to be prescription driven, but some over-the-counter sales did occur, especially when ability to pay seemed high or the chemist knew the customer. Chemists need accurate information on the drugs they sell as abortifacients, encouragement to promote pregnancy tests, training in encouraging women to see a provider prior to purchase, and visual and written material to hand out. Better adherence to existing regulations for all prescription drugs is important, but the best course is to increase the availability of low-cost, safe abortion services at primary care level.

Résumé

On a bien étudié la sécurité clinique, l'efficacité et l'acceptabilité de la mifépristone et du misoprostol en Inde, mais moins leur utilisation, leurs utilisateurs, la manière dont les femmes y ont accès et la perception de l'avortement médicamenteux chez les fournisseurs, les pharmaciens, les femmes et leurs partenaires. Cet article décrit un volet d'une étude, une enquête auprès de 209 pharmaciens, dans les États du Bihar et du Jharkhand en 2004. Seuls 34% des pharmaciens interrogés stockaient de la mifépristone et du misoprostol, le volume des ventes était faible et la demande portait plutät sur des préparations abortives moins coûteuses et souvent inefficaces. Les hommes achetaient plus fréquemment les médicaments abortifs que les femmes. Les pharmaciens savaient que la mifépristone et le misoprostol étaient délivrés sur ordonnance, mais ils connaissaient moins le dosage et les effets secondaires. La plupart des achats s'effectuaient sur ordonnance, mais quelques ventes libres se produisaient, particulièrement quand les clients étaient aisés ou connus des pharmaciens. Il faut donner aux pharmaciens des informations précises sur les médicaments qu'ils vendent comme abortifs et les encourager à promouvoir les tests de grossesse ; il doivent être formés à inciter les femmes à voir un praticien et disposer de matériel visuel et écrit à remettre avant l'achat. Il importe de mieux respecter la réglementation sur tous les médicaments sur ordonnance, mais le mieux serait d'élargir la disponibilité de services d'avortement peu coûteux et sûrs au niveau primaire des soins de santé.

Resumen

Aunque se ha estudiado a fondo la seguridad, eficacia y aceptación de la mifepristona y el misoprostol en la India, no se conoce mucho sobre cómo, por quién y por cuántas mujeres son utilizados, o cómo los prestadores de servicios de salud, los boticarios, las mujeres y sus parejas perciben al aborto con medicamentos. Este artículo informa de una encuesta realizada en el 2004 entre 209 boticarios, en los estados indios de Bihar y Jharkhand. Se encontró que sólo el 34% de los boticarios entrevistados tenían existencias de mifepristona y misoprostol, con ventas bajas y mayor demanda de abortivos más baratos y a menudo más ineficaces. Los boticarios sabían que la mifepristona y el misoprostol son fármacos de venta con receta, pero carecían de conocimientos sobre su dosificación y efectos secundarios. Aunque la mayoría de las ventas eran con receta, si se conocía al cliente o si su capacidad de pagar era alta, también se hacían ventas sin receta. Los boticarios necesitan información exacta sobre los fármacos que venden como abortivos, incentivos para promover las pruebas de embarazo, capacitación para motivar a las mujeres a acudir a un prestador de servicios, y material visual e impreso para distribuir antes de la compra de los fármacos. Aunque es importante observar mejor los reglamentos actuales referentes a los fármacos de venta con receta, aun mejor sería incrementar la disponibilidad de los servicios de aborto seguro y de bajo costo en el primer nivel de atención.

Mifepristone was licensed for use in India in 2002, following which four pharmaceutical companies began marketing the drug. This had risen to seven companies by mid-2005. Misoprostol has been available as a medication for gastric ulcer treatment, and as elsewhere its abortifacient use is off-label. In-country consensus protocols and guidelines for appropriate use of mifepristone-misoprostol for medical abortion in early pregnancy were developed in 2004 by a National Consortium, consisting of national and international experts,Citation1Citation2 but at this writing neither drug had been introduced into public sector health services.

Both mifepristone and misoprostol can be sold through chemist outlets but only on prescription (as Schedule H drugs, Drug and Cosmetics Rules, 1945). In addition, the Drug Controller of India registration for mifepristone requires product packaging to mention that it be used under the supervision of a gynaecologist.

Mifepristone is registered for use in the first 49 days (seven weeks) of pregnancy. The dosage of 600mg specified in the product insert is in line with labelling approved by the US Food and Drug Administration. The National Consortium's guidelines, however, recommend use of 200mg of mifepristone orally followed 48 hours later by 400mcg of oral misoprostol. The Consortium's guidelines also endorse medical abortion use for the first 56 days of pregnancy (eight weeks).

The use of medical abortion is subject to the provisions of the Medical Termination of Pregnancy (MTP) Act 1971, which limits legal abortion provision to obstetrician-gynaecologists or generalist providers (those holding an MBBS degree) who have been certified. However the MTP Rules were modified in 2003 so that, unlike with surgical abortions, site certification is not required provided the certified doctor has a demonstrable referral link to a certified centre for back-up care should the need arise.

The clinical safety, efficacy and acceptability of mifepristone with misoprostol in the Indian context have been well studied.Citation3Citation4Citation5Citation6 However, little has been systematically documented about their use or how key stakeholders perceive medical abortion. Ipas, in 2004, conducted a study in the states of Bihar and Jharkhand (where it has an ongoing programmatic commitment to improving access to safe abortion care), to gauge knowledge of and perceptions about medical abortion among women and men, and to study stocking and sales of abortifacient drugs by chemists and the use practices of mifepristone-misoprostol among abortion service providers. The full study has been documented elsewhere;Citation7 this paper presents part of the findings, that is, the data relating to the role of chemists.

Access to abortion services remains particularly poor in the study areas of Bihar and Jharkhand (the two were one state until 2000). Although more than 10% of the country's population lives in these two states, only 1.2% of all certified abortion facilities are located there.Citation8 Less than 1% of primary health centres provide abortion services, 95% of centres do not have a trained doctor and nearly all lack necessary equipment or even basic infrastructure like water and electricity.Citation9

Methodology and participants

In addition to the two state capitals, ten more district towns (five from each state) were randomly selected from a census listing of all such towns. From a list of commercial localities and major markets, 3-7 were randomly selected for each town, based on town size. All chemists in those localities were listed and categorised into large, medium or small outlets - three or more persons, two persons or one person at the counter, respectively. At least four chemists were selected per locality from among the listed chemists, using standard random sample selection techniques. All those who agreed to be interviewed and who mentioned at least one drug that they stocked and sold for abortion or for treating delayed periods were included. During pilot testing of the survey instruments, we realised that these terms were used synonymously by many respondents; hence we did not try to maintain a distinction between them. If a selected chemist did not sell such drugs, the next chemist on the list was substituted. Only one in three chemists approached in Bihar and one in two in Jharkhand met the inclusion criteria and agreed to participate. In all, 209 chemists were interviewed, including 68 from large outlets, 70 from medium outlets and 71 from small outlets. We attempted to interview the main person at each chemist shop, but often had to interview the person available at the counter. Data were collected using a pre-tested, structured questionnaire that included a few open-ended questions.

In order to understand the chemist-customer interaction in greater detail, nine additional in-depth interviews with chemist shop owners stocking mifepristone and misoprostol were conducted. The interviews included one each in the state capitals, Ranchi and Patna, six medium-sized outlets in towns (three in each of the two states) and one in a rural area near a district town.

Although direct observation of the chemist -customer interaction was not part of the study methodology, the researchers witnessed several of these interactions by chance, since they happened while an interview was taking place. These are reported when appropriate.

The full study also included a survey of 221 abortion providers, similarly selected from the same towns through a listing process, as well as in-depth interviews with a smaller number.

Lastly, the full study included a series of focus group discussions (FGDs), 12 with women and five with men. Two of the FGDs (one each with men and women) were conducted in an urban area of Jharkhand which was also the site of the quantitative survey. The remaining FGDs took place in rural areas; all but two of the villages were close to large towns similar to those included in the survey. Actual locations reflected the availability of community-based, non-governmental organizations (NGOs) or other partners who could help the researchers identify and contact appropriate respondents for the study. Male and female participants in FGDs were married and had at least one living child. Most participants in the women's group discussions were also members of self-help groups run by the local NGO that provided logistical support to the study. Thus, these women were likely to be more vocal and better informed than members of the larger community. Each FGD had 10-12 participants. The FGDs included a semi-structured discussion and a structured exercise in which a brief description of medical abortion with mifepristone-misoprostol was presented in a vignette and participant reactions probed.

Quantitative data were analysed with SPSS, while the qualitative data management software Atlas Ti was used to organise and code all textual data from the qualitative components.

While this paper focuses on the findings of the chemist survey and in-depth interviews, selected results from the wider study are presented to illustrate points related to the chemists.

Availability of drugs for menstrual regulation/abortion at chemist shops

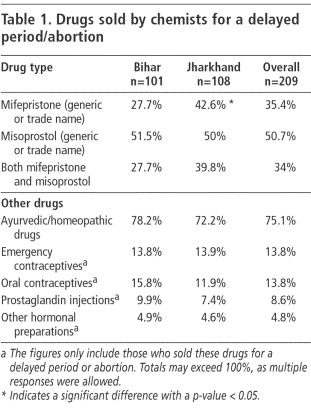

Table 1 represents the common drugs mentioned by chemists when asked to list drugs that they sold for a delayed period or abortion. Ayurvedic drugs were more likely to be sold than mifepristone or misoprostol. Only 34% of the surveyed chemists stocked both mifepristone and misoprostol tablets.

While the proportions of chemists selling other drugs as abortifacients was similar across states and chemist shop sizes, stocking patterns for mifepristone varied considerably. Stocking of mifepristone was significantly higher in Jharkhand than in Bihar, which may reflect a difference in the levels of urbanisation of the surveyed towns between the two states. Similarly, stocking was higher in the two state capitals (43.8% of chemists) than in the other district towns (32.9%). In both states, there was also a significantly higher probability of mifepristone being available at larger chemists (64.7% stocked it) than in medium-sized (22.9%) or small outlets (19.7%). Such variations were not seen with misoprostol, which has been in the Indian market for a longer time and is also a far cheaper drug.

An additional 24.4% of chemists said they were familiar with mifepristone but not willing to stock or sell it, mainly because of inadequate demand and the fact that it was expensive.

Although four brands each of mifepristone and misoprostol were available at the time of the survey, stocking of more than one brand was not common. Of the 74 chemists stocking mifepristone, 64% carried only a single brand, and 61% of the chemists stocking misoprostol also carried only a single brand.

In contrast, over 50 brands of Ayurvedic preparations were mentioned, the most common being Gynomic Forte, RP Forte and EP Forte. When asked how many Ayurvedic drugs he stocked for delayed periods, one chemist remarked: “How many names can I count? I keep so many.”

The authors collected samples of over 30 different preparations. None of the labels mentioned abortion as an indication, though some brands used clear mnemonic labelling - for example names like Abornil and DNC - to suggest that they were abortifacients (see photos). Several Ayurvedic preparations had names similar to EP Forte (e.g. Erca P Forte, E Pco. Forte), which we were told was to make them resemble the now-banned hormonal preparation EP Forte, to leverage the large-scale name recognition of that product.

Volume of sales

Chemists reported an average of two customers per week for mifepristone (range 1-21); sales volumes were higher at larger outlets than at medium- and smaller-sized ones. One chemist interviewed in-depth said: “People do not buy expensive drugs; the pack (pointing to a box of mifepristone) is lying here for two months.” Several chemists from medium- and small-sized outlets reported that because the volume was so low, they did not actually maintain a stock of the drug but obtained it only if a customer came in asking for it.

Chemists estimated four customers per week for misoprostol (range 1-286) with four chemists (all attached to large hospitals) reporting sales to more than 100 customers per week. It is possible that these higher misoprostol sales may be due to its use for other gynaecological indications as well as abortion, e.g. cervical priming, for which it is increasingly being used by providers in the area.

At the time of the study, the maximum retail price of the mifepristone brands ranged from Rs.310-325 (US$7.10-7.50). However, 48% of the chemists in Bihar and 6.9% in Jharkhand reported selling the brands in question at prices higher than the maximum retail price. Misoprostol was usually available at its retail price, which ranged from Rs.15-16.5 (US$0.35-0.37). All brands of mifepristone were available only in a pack containing three tablets; however, all the chemists selling it opened the packs and dispensed one or two tablets of mifepristone when requested.

Although we did not collect quantitative data on the volume of sales of other drugs meant for abortion, nearly all surveyed chemists agreed that the demand for other drugs was much higher, probably because of lower prices. One chemist situated in the state capital, describing the popularity of the Ayurvedic drug Gynomic Forte, said: “This is hot in the market; it sells like hot cakes everywhere in town. Everyone knows about this drug.”

That the demand for “other” drugs was high was corroborated in the FGDs as well. In all 12 FGDs with women, several of these medicines were mentioned by name and their use was thought to be a common first response when a woman's period was delayed. Respondents in the FGDs said that these medicines were usually obtained from a nearby chemist, though in some areas where local chemists did not exist, such drugs were also available at local grocery shops. In contrast, there was no spontaneous mention of mifepristone or misoprostol (or their trade names or medicines that sounded similar) and even after the vignette explaining these drugs was presented, it was only in the two FGDs in the district town in Jharkhand that a few participants thought these drugs were available locally.

What did chemists know about medical abortion?

Almost all of the 209 surveyed chemists (95%) mentioned medical representatives and doctors' prescriptions as their primary source of product information.

Further, when the 109 chemists stocking mifepristone and or misoprostol were asked whether they thought the drugs needed to be prescribed alone or in combination, 51 (46.8%) thought both needed to be used, 39 (35.8%) thought misoprostol alone was adequate and five (4.6%) thought mifepristone could be used by itself. The remaining 12.8% thought either drug could be used alone.

Over half the chemists who knew of both drugs (51.3%) were unable to answer what they thought the doses were at which the two drugs were used together. Some 15.6% mentioned the use of 200mg mifepristone followed by 400mcg misoprostol, as in the current National Consortium guidelines. An equal proportion thought that mifepristone should be used in doses of 600mg with 400mcg of misoprostol. This may reflect wider prescribing patterns in the study areas as during the interviews with service providers, we found that 65.1% of doctors providing mifepristone-misoprostol were giving mifepristone in doses greater than 200mg.

Twenty-seven per cent of chemists mentioned that misoprostol should be used vaginally rather than orally, and 7% thought that mifepristone too was usually prescribed vaginally, not orally.

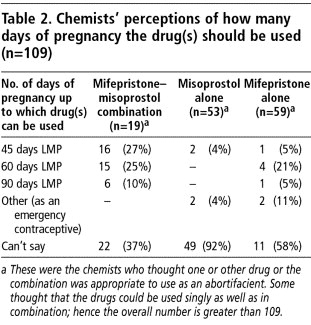

Many chemists were unable to answer how many weeks of pregnancy the drugs could be used until. Those who did answer felt largely that the drug should not be used beyond either 45 or 60 days after the last menstrual period (LMP) (Table 2).

Two chemists thought misoprostol should be used the same way as emergency contraception (that is, within 72 hours of unprotected sex) and two chemists thought mifepristone should be used in this way.

When asked what the side effects of these drugs were, 73% of chemists were unable to list any. Among those who did mention something, excessive bleeding was the most common response for both the combination regimen and for mifepristone alone. However, nausea and vomiting were thought to be the most common side effects when misoprostol was used alone.

All chemists interviewed thought that their current knowledge levels about mifepristone and misoprostol were inadequate and expressed a strong interest in learning more about the side effects of the drugs, legal issues, efficacy and mechanisms of action.

Who comes to buy abortifacient drugs?

Customers purchasing abortifacient drugs were often men, with 54.1% of the surveyed chemists estimating that over half of all customers for abortifacient drugs were men. This was reiterated by all nine chemists who were interviewed in depth. All nine chemists thought that women and even men were shy about asking for such drugs. One chemist running a medium-sized shop in a residential locality mentioned that men came to the shop only when other customers were not around.

The role of men as proxy customers also came out during the FGDs both with men and women. Here in all of the group discussions it was emphasised that since women especially in rural communities do not go out of their homes often and will not travel a large distance if unaccompanied, both husbands and boyfriends often played the role of intermediaries in going to the chemist outlet in order to purchase drugs. One chemist during an in-depth interview said: “Everyone who comes to buy the medicine says that he wants it for his wife. Now, I cannot tell whether that is his wife or friend!” Some men were thought to be servants sent by rich customers who did not want to be seen themselves at the chemist shop.

Women do go directly to purchase drugs as well, but sending proxies - a female friend or the local birth attendant (dai) - was mentioned in the FGDs as not uncommon, even when a woman has a prescription for the drugs from a doctor.

How many customers come with prescriptions?

There appear to be three distinct patterns of customers who come in to buy abortifacient drugs:

those who carry a doctor's prescription,

those who have the name of a specific drug in mind or carry a wrapper, empty packet or brand name written on a piece of paper (“Chutki” ), based on the recommendation of someone who has used these tablets successfully, and

those who rely on the chemist to recommend a suitable product.

Over 97% of surveyed chemists estimated that at least a few of their customers relied on them to recommend a suitable product, and nearly two-thirds of all chemists (61.7%) thought that more than half of their customers asked for a recommendation rather than a specific product.

On the other hand, when asked to estimate the proportion of their mifepristone customers who did not have a prescription, nearly a third of the respondents (32.1%) were unwilling to answer. Of those who did, the overwhelming majority (77.1%) felt that 80% or more of all mifepristone customers carried a prescription. In fact, 47% of those who answered the question said that not a single mifepristone customer was without a prescription. Their answers may be related to the high awareness levels of the Schedule H status of these drugs. When asked at the end of the survey about any specific rules or regulations pertaining to the sale of mifepristone, the vast majority of chemists (92.9%) mentioned that mifepristone could not be sold without a prescription. A similar proportion were aware that misoprostol is also a prescription drug. Four per cent of chemists, in addition, mentioned the Drug Controller of India's stipulation of using mifepristone only under a gynaecologist's supervision.

During the in-depth interviews as well, chemists spoke about rules and the publicity around possible problems with misuse of the drugs, and in fact four chemists had refused to participate in an in-depth interview as they were concerned that the researchers might be drug inspectors.

Interestingly, when surveyed doctors were asked if they thought the drugs should be sold by chemists on prescription, only 13.4% were in favour of this. However, when the sub-set of these doctors who were actually providing medical abortion in their clinical practice were asked how they supplied the drugs to women, only 24.7% said they kept a stock of drugs at their clinic, the rest all wrote out prescriptions and asked women to purchase them from nearby chemists.

However some non-prescription sales also do occur. Doctors too confirmed this; 16.3% of obstetrician-gynaecologists providing medical abortion reported that in the previous six months, they had also treated women (most often young, unmarried girls) who had come to them after having taken mifepristone and/or misoprostol obtained from a chemist.

How do chemists respond when asked to recommend drugs?

During the FGD discussions with men, they described a common pattern wherein the husband or other male relative of the woman with a missed period generally went to the chemist, described the problem and relied on the chemist to prescribe the appropriate medicine. Some men were said to approach the local chemist, not to obtain a medicine but to ask advice on the right doctor to consult for an abortion. Chemists reported that poorer customers were more likely to come in directly, without having first visited a doctor. Many asked for tablets for a “menstrual cycle that has stopped” . Others were more direct and explained that their wives did not want to continue the pregnancy. Most asked the chemist to suggest an appropriate drug, saying, for example: “Give me medicines according to your best understanding.”

While it was not discussed during the survey, in the nine in-depth interviews we tried to understand the basis upon which chemists made such recommendations. A clear and consistent pattern emerged, with the chemists' decision seeming to depend on several factors:

Knowing that the woman was pregnant and the duration of pregnancy

Three of the nine chemists reported that they advised women to do a urine test to confirm pregnancy before taking any medicines. These chemists all sold the pregnancy test strips to the woman or her partner. Others said they asked the person to estimate the duration of pregnancy but admitted they had to rely on the person's own estimation.

Belief in the relative efficacy of the drugs

Two chemists seemed to be aware of the distinction between menstrual irregularity (delayed periods) and an actual pregnancy; they felt that most of the Ayurvedic or hormonal drugs they stocked worked only if the woman was not pregnant. The other seven believed that these other drugs were effective as abortifacients if used early enough in pregnancy. Six of the nine chemists believed that all drugs worked equally well, with mifepristone-misoprostol being marginally more effective, and thus that there was little to choose between the various drugs. This was expressed in various ways:

“Mifepristone-misoprostol is good but Gynomic Forte is also effective, as there is demand for the product.”

“Mifepristone-misoprostol has nearly 100% guarantee, but others are also 60-70%.”

“All drugs are effective for three months.”

Some chemists did think that mifepristone and misoprostol were more effective than the other drugs; however, the belief that mifepristone was better was often due to its higher price, with cost being a proxy for quality.

Economic considerations

This factor usually overrode all others. Eight of the nine chemists reported deciding on which drug to prescribe based on their estimate of the customer's ability to pay. The bottom line for most chemists was to ensure that no one went away from the shop without buying a medicine.

“We see pockets first.”

“It's just like gambling. It all depends on what they want and can afford.”

“I'm a businessman, and I have to see to the needs according to their pockets. I assess them by how they look; I mean, their dress-up and the way they talk. Whom I consider to be poor, I give them drugs which cost Rs.40-50. And whom I consider to be rich and can afford, I cannot give them cheap drugs because they won't believe in it. So my recommendation completely depends on their pockets.”

Whether or not the chemist knows the customer personally

Chemists were more willing to “take risks” with people known to them personally in that they were more likely to provide mifepristone in the absence of a prescription. Six chemists mentioned this and the authors had a chance to observe this firsthand when, during one in-depth interview, a male customer walked in and told the chemist his wife was pregnant and wanted to abort. The man said that he “needed some good medicine for the purpose” . The chemist asked him, “How many months have passed?” The man said it was a little less than one and a half months since the first day of the last period. The chemist told the man to return in the evening for the medicine and instructions on how to use it. The chemist, continuing with the interview, explained to the interviewers that he would be recommending the mifepristone-misoprostol combination, as the man was a regular customer to the shop and known to the shop owner.

The most interesting differential in recommendations came in response to the question of what chemists would advise a family member or close friend who needed to have an abortion. Except for one chemist who claimed his advice was the same no matter for whom, the other eight said that for a family member, they would never want to take a risk and would always advise visiting a doctor before taking any kind of medication. “Our people are ours.”

What information is passed on to customers?

Not a single surveyed chemist passed on the product insert of the drugs when selling them, and no other written material or instructions were available from any chemist. However, 54.1% said they instructed the customer verbally to go to a doctor in case of problems like excessive bleeding, vomiting or if the abortion does not take place. Only 5.5% mentioned that they gave information on dosage.

When probed specifically on whether they advised consulting a doctor prior to starting the tablets, almost all chemists (91.7%) said that they did emphasise this, irrespective of whether the customer had a prescription.

Follow-up of customers who bought drugs

A customer is not expected to return to the chemist to report on the success or otherwise of any abortifacients purchased, nor did any chemists advise this. However, 32 of the interviewed chemists indicated that customers sometimes did come back to them for advice if the tablets did not work. When asked what their advice was, 27 of the 32 (84%) said that they advised going to a doctor; the rest said they suggested taking the medicines again but this time in doses twice that used the previous time.

This issue was probed further during the in-depth interviews. Six of the nine chemists said that their advice to those who came back to report a failure depended on what the initial treatment had been. If the initial medicines taken were Ayurvedic or hormonal, they first recommended an alternative line of treatment. If that too failed, they suggested a visit to the doctor. For example:

“First we give Gynomic Forte; if it does not work, we give Aromic Forte. If that does not work, we give misoprostol then mifepristone, and finally we suggest go to madam [nearby gynaecologist].”

Drug substitution

During the in-depth interviews, chemists were asked what they would do if they did not have the drug a customer requested or had a prescription for. Several said that, in such circumstances, they substituted other drugs, trying to provide a drug of equivalent cost.

“See, my clients have no idea about the drugs, names, their effectiveness. When I substitute one drug for another, they never say a thing because they know only that the name is different, or the company making the drug is different, but the purpose of the medicine - that is the same, and all my clients are well aware of it.”

Six of the nine chemists said that when the prescription is for mifepristone and it is not in stock, they have no option but to turn the person away, as there are no other abortifacient drugs in that price range that can be substituted.

Discussion

In India, as in other South Asian countries,Citation10 a variety of over-the-counter medications for delayed periods/abortion remains in high demand because of low cost and because the perception that side effects are negligible makes the trade-off with low efficacy worthwhile. While the price of mifepristone in India is less than in many other countries, a single tablet still costs 8-10 times more than any of the other preparations and even in absolute terms can prove a considerable barrier in these two states, both of which have a per capita income considerably lower than the national average. The fact that higher than necessary doses of mifepristone continue to be prescribed and sold increases costs and further reduces access and therefore demand.

This coupled with the fact that not all chemists were convinced of or educated about the comparative advantage of mifepristone-misoprostol and were unwilling to risk possible failure or complications may be responsible for the fact that while over-the-counter sales do happen, the majority of transactions still appear to be prescription driven. Additionally, awareness of the rules relating to the drugs and publicity around potential misuse have also been high.

It is possible that with time, as prescription sales increase and customer demand rises, chemists' own perceptions will change and non-prescription sales will likely increase as well. Hence, the current scenario provides us with a window of opportunity for action.

The confusion between emergency contraceptives and abortifacients among some chemists is a cause for concern, as is the lack of understanding among many chemists of the efficacy or otherwise of the innumerable drugs that they stock as abortifacients. Even if not harmful, their use delays care-seeking and means abortions are finally carried out later than necessary. Dissemination of accurate information on these drugs to chemists, as well as on mifepristone-misoprostol, is essential. Research is also needed to determine whether any of the Ayurvedic drugs is effective as well. Encouraging chemists to stock and promote the use of inexpensive and easily available pregnancy tests can help to shift abortion care-seeking to earlier in pregnancy and would serve as appropriate advice of the first step to take for those who come in and ask about dealing with an unwanted pregnancy.

While chemists may not be obliged to provide any additional information, and there may be some who argue that providing people with additional product information may only lead to more over-the-counter sales, the fact remains that even customers carrying a prescription for mifepristone and misoprostol ask chemists to reconfirm dosage and directions for use; hence, basic information about these drugs is needed by chemists. The fact that most surveyed chemists emphasised the need to consult a doctor, even to people with prescriptions, is an encouraging sign. As most of the providers interviewed were prescribing rather than stocking the drugs themselves, it can be expected that women will go to (or return to) chemists to purchase the drugs.

Providing chemists with educational material on abortion and abortifacient drugs that they can provide to customers at the time of drug sales may also be useful, and seen as an add-on value by chemists. Keeping in mind the low literacy level in these two states, materials that rely on pictorial messaging will be needed. Equally important will be material that targets men who purchase drugs for women. NGOs are ideally placed to adapt existing national and international guidelines into contextual and culturally sensitive information.

Schedule H regulations require chemists to maintain a record of sales and of the prescribing doctor. Numerous other Schedule H drugs, such as antibiotics, are all available over the counter to varying degrees, which suggests that the problem is not unique to mifepristone-misoprostol or indeed to abortion, but is a larger problem of regulation of drugs in general. Self-regulation among the pharmaceutical companies and better enforcement of drug regulations need to be encouraged for all drugs, not just abortifacients.

The risks of using abortifacient drugs without medical oversight will remain a real one in a context where access to safe services remains limited - whether by the law as in Latin America and elsewhere or by poor implementation, as in most of Bihar and Jharkhand. The safeguards do not lie in clamping down on chemists as this will only reduce access to prescription sales. The solution lies in making it less likely that women will opt for unsupervised use by ensuring that medical abortion - and other types of abortion - are legally available at low cost through trained providers in services that are conveniently accessible. This means introducing the drugs into the public sector at primary health centre level as soon as possible, and over the longer term training a wider pool of providers, including mid-level providers.

Acknowledgment

This study was supported by a grant from the David and Lucille Packard Foundation to Ipas. The findings in this paper are drawn from the full report of the study findings.Citation7 The authors thank the research team and many colleagues who contributed to the full study. The inputs of Traci Baird in converting the report findings into this paper are gratefully acknowledged.

References

- S Mittal. Consortium on National Consensus for Medical Abortion in India: Proceedings and Recommendations. 2004; All India Institute of Medical Sciences: New Delhi.

- All India Institute of Medical Sciences. Use of RU 486 with Misoprostol for Early Abortion in India. Guidelines for medical officers. 2004; AIIMS: New Delhi.

- A Banerjee, S Tewari. Clinical cum socio behavioral evaluative study of women seeking termination of early pregnancy (up to 56 days LMP). 2004; Parivar Seva Sanstha: New Delhi.

- K Coyaji, B Elul, U Krishna. Mifepristone abortion outside the urban research hospital setting in India. Lancet. 357: 2001; 120–121.

- K Coyaji, B Elul, U Krishna. Mifepristone-misoprostol abortion: a trial in rural and urban Maharashtra, India. Contraception. 66(1): 2002; 33–40.

- B Winikoff, I Sivin, KJ Coyaji. The acceptability of medical abortion in China, Cuba and India. International Family Planning Perspectives. 23(2): 1997; 73–78.

- Ganatra B, Manning V, Pallipamulla S. Medical abortion in Bihar and Jharkhand: A study of service providers, chemists, women and men. New Delhi: Ipas, 2005.

- ME Khan, S Barge, N Kumar. Abortion in India: current situation and future challenges. S Pachauri. Implementing a Reproductive Health Agenda in India: The Beginning. 1999; Population Council: New Delhi, 507–529.

- Indian Institute for Population Sciences. Report of the Facility Survey under the Reproductive and Child Health (RCH) Project. 2001; IIPS: Mumbai.

- A Tamang, J Tamang. Availability and acceptability of medical abortion in Nepal: health care providers' perspectives. Reproductive Health Matters. 13(26): 2005; 110–119.