Abstract

In the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, the foundation of human rights, the text and negotiating history of the “right to life” explicitly premises human rights on birth. Likewise, other international and regional human rights treaties, as drafted and/or subsequently interpreted, clearly reject claims that human rights should attach from conception or any time before birth. They also recognise that women's right to life and other human rights are at stake where restrictive abortion laws are in place. This paper reviews the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, the Convention on the Rights of the Child, and the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women, the European Convention for the Protection of Human Rights and Fundamental Freedoms, the Inter-American Human Rights Agreements and African Charter on Human and People's Rights in this regard. No one has the right to subordinate another in the way that unwanted pregnancy subordinates a woman by requiring her to risk her own health and life to save her own child. Thus, the long-standing insistence of women upon voluntary motherhood is a demand for minimal control over one's destiny as a human being. From a human rights perspective, to depart from voluntary motherhood would impose upon women an extreme form of discrimination and forced labour.

Résumé

Dans la Déclaration universelle des droits de l'homme, fondement des droits de l'homme, le texte du « droit à la vie » et l'histoire des négociations l'entourant supposent explicitement que les droits fondamentaux commencent à la naissance. De même, d'autres traités internationaux et régionaux des droits de l'homme, tels qu'ils ont été rédigés et/ou interprétés par la suite, rejettent clairement l'idée de droits de l'homme garantis depuis la conception ou avant la naissance. Ils reconnaissent aussi que le droit des femmes à la vie et d'autres droits fondamentaux sont en jeu quand des lois restrictives sur l'avortement sont en vigueur. L'article examine dans cette perspective le Pacte international relatif aux droits civils et politiques, la Convention relative aux droits de l'enfant, la Convention sur l'élimination de toutes les formes de discrimination à l'égard des femmes, la Convention européenne de sauvegarde des droits de l'homme et des libertés fondamentales, la Convention américaine relative aux droits de l'homme et la Charte africaine des droits de l'homme et des peuples. Personne n'a le droit de subordonner autrui, comme une grossesse non désirée subordonne une femme et l'oblige à risquer sa santé et sa vie pour sauver le fætus qu'elle porte. Quand elles demandent une maternité choisie, les femmes souhaitent donc pouvoir maîtriser de manière minimale leur destin en tant qu'être humain. Dans la perspective des droits de l'homme, refuser la maternité choisie revient à imposer aux femmes une forme extrême de discrimination et de travail forcé.

Resumen

En la Declaración Universal de Derechos Humanos, la fundación de los derechos humanos, el texto y la historia de negociaciones respecto al “derecho a la vida” expone explícitamente los derechos humanos a partir del nacimiento. Asimismo, otros tratados internacionales y regionales de derechos humanos, tal como fueron redactados o posteriormente interpretados, rechazan las afirmaciones de que los derechos humanos son vigentes a partir de la concepción o cualquier momento antes del nacimiento. Además, reconocen que el derecho de las mujeres a la vida y otros derechos humanos están en juego donde existen leyes restrictivas de aborto. En este artículo se examina el Pacto Internacional de Derechos Civiles y Políticos, la Convención sobre los Derechos del Niño, la Convención sobre la Eliminación de Todas las Formas de Discriminación contra la Mujer, la Convención Europea para la Protección de los Derechos Humanos y de las Libertades Fundamentales, los Acuerdos Interamericanos de Derechos Humanos y la Carta Africana de Derechos Humanos y de los Pueblos. Nadie tiene el derecho de subordinar a otra persona de la manera en que el embarazo no deseado subordina a la mujer y la obliga a arriesgar su salud y su vida para salvar el feto que lleva. Por tanto, al insistir que la maternidad sea voluntaria, las mujeres exigen control mínimo sobre su propio destino como seres humanos. Desde el punto de vista de los derechos humanos, el alejarse de la maternidad voluntaria impondría sobre las mujeres una forma extrema de discriminación y trabajo de parto forzado.

At the 1994 International Conference on Population and Development (ICPD) in Cairo, the Vatican delegation proposed that the “right to life” be included among the principles that guide the Programme of Action, although it never formally advanced the position in negotiation that the fetus should be recognised as having human rights. Since the right-to-life language had been so improperly co-opted by the anti-abortion forces, the Women's Caucus at the ICPD, comprised of NGO participants from around the world, was duly suspicious. At the same time, it was important not to cede the “right to life” to the right-wing, but rather to have international recognition that women's right to life is at stake when reproductive rights and health are denied in general, and in particular, when women are denied safe, legal abortion.Citation1Citation2Citation3

The stalemate was resolved by including the historic first sentence of Article 1 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR), the foundation of international human rights, as the opening sentence of the Principles chapter of the ICPD Programme of Action, which provides:

“All human beings are born free and equal in dignity and rights. Everyone is entitled to all the rights and freedoms set forth in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, without distinction of any kind, such as race, colour, sex, language, religion, political or other opinion, national or social origin, property, birth or other status. Everyone has the right to life, liberty and security of person.” Citation4 (emphasis added)

This language, dating human rights from birth, was accepted almost unanimously, with objection from only a tiny minority of states.Citation5 Footnote* The recognition that human rights are the foundation of population and development policies was a fundamental goal of the Women's Caucus. It underpinned later chapters of the ICPD Programme, such as Chapter IV on gender equality, equity and empowerment of women and Chapter VII on reproductive rights and health.Citation4 It also represented a significant step beyond the ambiguous international recognition in the 1974 and 1984 World Population Conferences that “…couples and individuals have the right to decide freely and responsibly the number and spacing of their children and to have the education, information and means to do so” .Citation6 The broad and prominent recognition of human rights in the Cairo Programme was also a crucial antidote to the explicit though literally subordinate role for sovereignty and cultural relativism in the opening paragraph of the Principles Chapter, which emphasised state sovereignty in the implementation of the Programme and “full respect for the various religious and ethical values and cultural backgrounds of its people, and in conformity with universally recognised international human rights” (Ch.1, Para.1.11).Citation4

More recently, advocacy for a fetal “right to life” has emerged in a variety of efforts to invalidate or undermine liberal abortion laws in a number of states. The European Court of Human Rights was asked, and refused, to require France to prosecute a doctor for manslaughter for negligent antenatal care that necessitated an abortion of a wanted pregnancy.Citation7 Conservative parliamentarians in Slovakia - having lost the legislative battle - are seeking a ruling from the Slovakian Constitutional Court that Slovakia's broad permission for abortion in the first trimester and thereafter when a woman's life would be endangered by continued pregnancy is inconsistent with a presumed fetal right to life. Their position is based not only on a distortion of Slovakia's Constitution, but also on the claim that the European Convention of Human Rights (ECHR) and international law do not preclude recognition of fetal rights. Reproductive rights activists in other countries have also signalled concern that the purported fetal rights claim is being used to prevent liberalisation of abortion laws or to challenge them altogether.

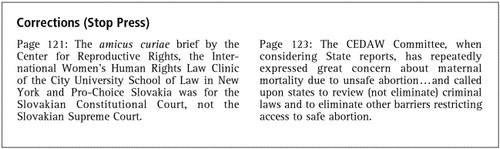

All this pointed to the need to examine the history of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights's explicit dating of rights from birth as well as other international sources relating to the right to life, and to be prepared to provide this information to courts and legislatures faced with such claims. Accordingly, the Center for Reproductive Rights, the International Women's Human Rights Law Clinic of the City University School of Law in New York and Pro-Choice Slovakia collaborated on the preparation of Comments, in the nature of an amicus curiae (friend of the court) brief for the Slovakian Supreme Court. The Comments defend the liberal abortion law based on the impermissibility of according rights to the fetus and canvasses the recognition of women's right to abortion on a number of human rights grounds. The Comments will soon be available through the Internet and can be used in response to similar challenges.

This article will summarise the points made in the Comments regarding the rejection, in the negotiating history of the foundational human rights documents and/or in subsequent authoritative interpretations, of the claim that the fetus has a right to life. We note in conclusion that the most powerful answer to the fetal rights claim is the breadth of women's human rights that would be at stake were the claim of overriding fetal rights to be accepted.

International instruments

The Universal Declaration of Human Rights

Article 1 opens the Universal Declaration of Human Rights with the fundamental statement of inalienability: “All human beings are born free and equal in dignity and rights” (Art.1).Citation8 Significantly, the word “born” was used intentionally to exclude the fetus or any antenatal application of human rights. An amendment was proposed and rejected that would have deleted the word “born” , in part, it was argued, to protect the right to life from the moment of conception.Citation9 The representative from France explained that the statement “All human beings are born free and equal…” meant that the right to freedom and equality was “inherent from the moment of birth” (p.116).Citation9 Article 1 was adopted with this language by 45 votes, with nine abstentions.Citation10 Thus, a fetus has no rights under the Universal Declaration of Human Rights. The deliberately gender-neutral term “everyone” (p.233),Citation11 utilised thereafter in the Declaration to define the holders of human rights, refers to born persons only.

The International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights

The International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR)Citation12 likewise rejects the proposition that the right to life, protected in Article 6(1), applies before birth. The history of the negotiations (travaux préparatoires) indicates that an amendment was proposed and rejected that stated: “the right to life is inherent in the human person from the moment of conception, this right shall be protected by law.” Citation13Citation14 The Commission ultimately voted to adopt Article 6, which has no reference to conception, by a vote of 55 to nil, with 17 abstentions.Citation15

Subsequently, the Human Rights Committee, which interprets and monitors States parties' compliance with the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, has repeatedly emphasised the threat to women's lives posed by prohibitions on abortion that cause women to seek unsafe abortions. It has also repeatedly called upon states to liberalise criminal laws on abortion,Citation16Citation17Citation18Citation19Citation20Citation21Citation22Citation23 Footnote* a position that would be problematic if the Covenant's protection of the right to life extended before birth.Citation24Citation25Citation26Citation27Citation28 In an authoritative interpretation of the principle of equality protected by the Convention, the Committee has also emphasised the states' responsibility to eliminate women's mortality from clandestine abortion and recognised that such criminal laws could violate women's right to life (Para.10).Citation29

The Convention on the Rights of the Child

Likewise, both the negotiations (travaux préparatoires) and the interpretation by its expert treaty body make clear that the Convention on the Rights of the Child (CRC)Citation30 does not recognise the right to life until birth. An argument to the contrary is erroneously built upon Paragraph 9 of its Preamble, which provides: “Bearing in mind that, as indicated in the Declaration of the Rights of the Child, ‘the child, by reason of his physical and mental immaturity, needs special safeguards and care, including appropriate legal protection, before as well as after birth.’” (Preamble, Para.9)Citation30 This reflects, at most, recognition of a state's duty to promote, through nutrition, health and support directed to the pregnant woman, a child's capacity to survive and thrive after birth.

The travaux make clear that this duty must not affect a woman's choice to terminate an unwanted pregnancy. As originally drafted, the Preamble did not contain the reference to protection “before as well as after birth,” although this language had been used in the earlier Declaration on the Rights of the Child. The Holy See led a proposal to add this phrase, at the same time as it “stated that the purpose of the amendment was not to preclude the possibility of an abortion” .Citation31 Although the words “before or after birth” were accepted, their limited purpose was reinforced by the statement that “the Working Group does not intend to prejudice the interpretation of Article 1 or any other provision of the Convention by States Parties” (p.10, p.59, p.145).Citation32Citation33Citation34Footnote* The reference is to the definition of “a child” . Article 1 states: “For the purposes of the present Convention a child means every human being below the age of 18 years…” Citation30 which, consistent with the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, refers only to born persons.

The Committee on the Rights of the Child, the expert treaty body that interprets and applies the Child Rights Convention, likewise denies a right to life to the fetus. The Committee has expressed repeated concern over adolescent girls' access to safe abortion services and the need for states “to provide access to sexual and reproductive health services, including... safe abortion services” .Citation35 (emphasis added) In its Concluding Observations on various State reports, the Committee has also recognised that safe abortion is part of adolescent girls' right to adequate health under Article 24, noting that “high maternal mortality rates, due largely to a high incidence of illegal abortion” contribute significantly to inadequate local health standards for children.Citation36Citation37Citation38 It has also explicitly called for “review of [state practices]… under the existing legislation authorising abortions for therapeutic reasons with a view to preventing illegal abortion and to improving protection of the mental and physical health of girls” .Citation37Citation38 It is clear that the definition of “a child” for purposes of the Convention does not include a fetus.

Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women

The Women's ConventionCitation39 does not explicitly protect the right to life or the right to abortion. Its Preamble does however reaffirm the Universal Declaration of Human Rights's recognition that “all human beings are born free and equal in dignity and rights” and states that “everyone is entitled to all the rights and freedoms set forth therein, without distinction of any kind, including distinction based on sex…” . The Convention also provides the general foundation for reproductive rights in Article 16(e) guaranteeing women “the same rights to decide freely and responsibly on the number and spacing of their children and to have access to the information, education and means to enable them to exercise these rights” .

Because of the inextricable inter-relationship between the right to make reproductive decisions and women's equal right to life, the CEDAW Committee has frequently had occasion to address issues concerning abortion and the status of fetal life in the context of women's equality. Thus, in its General Recommendation 21: Equality in Marriage, the Committee made clear that equality of rights to reproduce is not consistent with spousal veto of abortion (Para.21):

“The responsibilities that women have to bear and raise children affect their right of access to education, employment and other activities related to their personal development. They also impose inequitable burdens of work on women. The number and spacing of their children have a similar impact on women's lives and also affect their physical and mental health, as well as that of their children. For these reasons, women are entitled to decide on the number and spacing of their children.” Citation40

In General Recommendation 24: Health,Citation41 the CEDAW Committee recognises the importance of women's right to health during pregnancy and childbirth as closely linked to their right to life. The Committee explained that coverage of reproductive health services is an essential aspect of women's equality, stating that “it is discriminatory for a State party to refuse to legally provide for the performance of certain reproductive health services for women” . It describes as barriers to appropriate health “laws that criminalize medical procedures only needed by women and that punish women who undergo those procedures” (Para.14), as well as high fees, requirements of parental, spousal or hospital authorisation, and inaccessibility because of distance and/or travel barriers (Para.21).Citation41 Further, when considering State reports, the Committee has repeatedly expressed great concern about maternal mortality due to unsafe abortion, framed the issue as involving a woman's right to life, and called upon states to eliminate criminal laws and other barriers restricting access to safe abortion (p.145-46).Citation42

Regional treaties

The European Convention for the Protection of Human Rights and Fundamental Freedoms

The drafters of the European Convention for the Protection of Human Rights and Fundamental Freedoms (ECHR)Citation43 relied heavily on the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and, according to the history, did not even debate the question of dating rights from conception.Citation44 They based the European Convention's protection of everyone's right to life in Article 2 on parallel language in Article 3 on the “moral authority and technical value” of the Universal Declaration.Citation8Citation44 The Preamble to the European Convention repeatedly cites the Universal Declaration and declares that the purpose of the Convention is to “take the first steps for the collective enforcement of certain of the rights stated in the Universal Declaration” (Para.6).Citation43 In this light, it is manifest that the term “everyone” used throughout the European Convention as well as in Article 2 protecting the right to life likewise does not apply before birth.Footnote*

The long-standing jurisprudence of both the European Commission on Human Rights and the European Court establish that the fetus is not a human being entitled to the “right to life” under Article 2(1) and, further, that granting the fetus human rights would place unreasonable limitations on the rights of women.

In l980, Paton v. United Kingdom,Citation45 a case by a husband seeking to prevent his wife's abortion, explicitly rejected the claim that the right to life in Article 2 covered the fetus. The European Commission held that the word “everyone” in Article 2, and elsewhere in the Convention, did not include fetuses. Further, recognising the inseparability of the fetus and the pregnant woman, it gave precedence to the woman's rights under Article 2 (Paras.7-9): Citation45

“The life of the fetus is intimately connected with, and it cannot be regarded in isolation of, the life of the pregnant woman. If Article 2 were to cover the fetus and its protection under this Article were, in the absence of any express limitation, seen as absolute, an abortion would have to be considered as prohibited even where the continuance of the pregnancy would involve a serious risk to the life of the pregnant woman. This would mean that the “unborn life” of the fetus would be regarded as being of a higher value than the life of the pregnant woman.” (Para.19)Citation45

Paton was followed in R.H. v. Norway (1992)Citation46 and Boso v. Italy (2002),Citation47 likewise cases brought by husbands seeking to prevent their wives' abortions based on the right to life of the fetus, but which sustained the permissive abortion laws at issue.

Most recently, in Vo v. France (2004),Citation7 the Court again refused to extend the right to life to fetuses. The female applicant in this case had wanted to carry her pregnancy to term but had to have a therapeutic abortion due to medical negligence. Represented by anti-abortion lawyers, her case asserted that the negligence of the doctor that necessitated the abortion was a violation of the fetus' right to life under Article 2 of the Convention and, therefore, required prosecution of the doctor for unintentional homicide instead of the lesser charge of malpractice or regulatory violation as provided by French law (Paras.50,89,92,93).Citation7 Again the Court affirmed that “the unborn child is not regarded as a ‘person’ directly protected by Article 2 of the Convention,” and that if the unborn do have a ‘right’ to ‘life’, it is implicitly limited by the mother's rights and interests” (Para.80).Citation7 Noting that “there is no European consensus on the scientific and legal definition of the beginning of life” (Para.84),Citation7 the Court declined to treat the fetus as a “person” or require a homicide prosecution even though, as in this case, there was no conflict with the rights of the woman (Paras.89,92,93).Citation7 This decision protects all of Europe's liberal abortion laws, as well as doctors and providers, from being deterred from providing abortions for fear of such sanction. As such, Vo also protects women's access to reproductive health care, including abortion, as well as the broad range of obstetric care.

The European Commission and Court have thus repeatedly reaffirmed in the cases brought before them that the Convention protects women's fundamental right to a safe abortion. Although the European jurisprudence recognises some discretion in the States to balance protection of fetal life against the human rights of women, it has never invalidated a permissive abortion law nor stated (or been required to state) to what extent European law requires legalisation of abortion.

The Inter-American Human Rights Agreements

The first paragraph of the Preamble of the inter-American human rights system, the American Declaration on the Rights and Duties of Man, contains the same language as the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, premising rights on birth, stating: “All men are born free and equal in dignity and rights” (Preamble, Para.1).Citation48Footnote* The jurisprudence of the Inter-American system likewise rejects the claim that the fetus is entitled to a right to life. In particular, Article 4 of the American Convention on Human Rights, which protects the right to life “in general, from the moment of conception” ,Citation49 (emphasis added) has been interpreted by the Inter-American Commission not to confer an equivalent right to life on the fetus or require invalidation of permissive abortion laws.Citation50 Challenging the refusal of a US state court to convict a doctor of murder for having performed a late-term abortion, anti-abortion advocates in the US brought the case under the American Declaration on the Rights and Duties of Man, which protects the right to life with no reference to the “moment of conception” (Ch.1, Art.1).Citation48 The Commission rejected the petitioners' claim under the Declaration (Para.18);Citation50 it also interpreted Article 4 of the American Convention,Citation49 in light of its drafting history, to preclude a right to life for the fetus, stating:

“The addition of the phrase, ‘in general, from the moment of conception’ does not mean that the drafters of the Convention intended to modify the concept of the right to life that prevailed… when they approved the American Declaration. The legal implications of the clause ‘in general, from the moment of conception’ are substantially different from the shorter clause ‘from the moment of conception’ as appears repeatedly in the petitioner's briefs.” (Para.30)Citation50

African Charter on Human and People's Rights

In the African Union, the protection of a broad right to abortion is explicit. On 11 July 2003, the African Union adopted the Protocol on the Rights of Women in AfricaCitation51 to supplement the 1981 African Charter on Human and Peoples' Rights.Citation52 The Protocol, which will enter into force once it has been ratified by 15 African states, represents the first time that an international human rights instrument has explicitly articulated a right to abortion. It recognises the duty of the state to take “all appropriate measures…to protect the reproductive rights of women by authorising medical abortion in cases of sexual assault, rape, incest, and where the continued pregnancy endangers the mental and physical health of the mother or the life of the mother or the fetus” (Art.14[2][c]).Citation51Citation53

At the same time, the l999 African Charter on the Rights and Welfare of the Child provides in Article 5(1): “Every child has an inherent right to life. This right shall be protected by law.” Citation54 Read together, the two instruments make clear that the right to life referred to in the African Charter is not meant to apply prenatally or to protect a fetus where that would contradict the right of women to abortion.

Conclusion

The argument against recognising rights before birth has many practical and theoretical foundations. The scientific or medical impossibility of stating when conception occurs or human life begins, and the philosophical and religious diversity of opinion worldwide as well as within countries was, in the past, sufficient basis for rejecting the claim for fetal rights, and these factors continue.

In recent decades, however, the rejection of claims for “fetal rights” has been increasingly grounded, and most significantly so, on their incompatibility with women's human rights.Footnote* To do otherwise, would reduce women to a vessel - and yet a human one - deprived of bodily integrity, the right to be sexual and the right to life, not only in the physical sense illustrated by abortion-related maternal mortality but also as sentient, feeling, and rational beings entitled to shape their lives, to resist the dictates of others, to be respected as full persons, to be other than a mother, and to undertake the enormous responsibilities of pregnancy and parenthood, not by force or coercion, but as a voluntary undertaking - out of desire and as a gift.

The long-standing and constantly re-enacted insistence of women, written largely in their blood, upon voluntary motherhood is at its foundation both a demand for minimal control over one's destiny as a human being and a refusal to be enslaved to another whether that be the advocate or enforcer of patriarchal obligation or its surrogate, the fetus. It is for this reason that the careless, but at first blush seemingly logical assertion that fetal personhood would extinguish a women's right to abortion is wrong (Para.19)Citation45 (Pt. IX-A).Citation62 No fully developed person has the right to subordinate another in the way that unwanted pregnancy subordinates a woman. Nor is any fully developed person required to risk their health or life or even significant comfort to save another person, even their own child. To impose upon a full human being such subordination and risk for the sake of potential human life, is, by contrast, absurd as well as cruelly unfair. Pregnancy is the most intimate and continual form of labour and rescue, and like labour and rescue, it must be voluntary. Abortion is, thus, for theoretical and practical reasons indispensable to women's equality, dignity and rights as a human being (p.1021-24).Citation67Citation68Citation69Citation70Citation71

Notwithstanding vociferous opposition from religiously-driven delegations in the United Nations process, who also deny the right of women to equality, women's human right to make decisions over whether and when to bear a child has been increasingly recognised as fundamental. The right to voluntary motherhood and thus to decide the question of abortion is integral to a broad range of fundamental human rights, specifically, women's rights to equality, life, health, security of person, private and family life, freedom of religion, conscience and opinion, and freedom from slavery, torture and cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment - all of which take precedence over claims to protection on behalf of the fetus. Examining the consequences of restrictive abortion laws through the lens of their respective Conventions, the treaty bodies responsible for overseeing implementation of civil and political rights, the protections against torture and cruelty, inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment, economic and social rights, the rights of women and the rights of the child have recognised the negative impact that restrictive abortion laws have on the realisation of human rights and condemned restrictive or punitive practices. Discussion of these developments, as well as other documents reflecting acceptance of reproductive rights, including abortion, is beyond the scope of this article but there are excellent sources available.Citation42Footnote*

The worldwide trend in recent decades has been towards liberalisation of restrictive laws. Some states have followed the advice of the treaty bodies while, in others, reproductive rights advocates are strengthened by international recognition in their efforts to ensure access to safe, legal abortion. At the same time, the growing power of religious extremism in many parts of the world, especially in the United States, heightens the danger to reproductive rights. Efforts to undo progressive abortion legislation, such as that enacted in Slovakia, are likely to multiply. In this conflict, it is not insignificant that from their inception and as a matter of international law, human rights begin at birth.

Notes

* Regarding Principle 1, Argentina orally associated itself with the written reservation from El Salvador stating that life must be protected from the moment of conception (Para. 21). Guatemala submitted a written statement also asserting that life exists from the moment of conception (Para. 26).Citation5

* For example, the Concluding Comments on Chile state: “The criminalization of all abortions, without exception, raises serious issues, especially in the light of unrefuted reports that many women undergo illegal abortions that pose a threat to their lives…The Committee recommends that the law be amended so as to introduce exceptions to the general prohibition of all abortions...” Citation17

* One commentator explains that the inclusion of this statement was in fact unnecessary, as the Preambular language does not legally obligate states to provide protection for the unborn, nor does it define the moment at which a fetus becomes a child (p.146-47).Citation37

* It appears that the European Court on Human Rights did not have this history of the Universal Declaration before it in Vo, when it opined that no one knew the meaning of “everyone” (Para.84).Citation7

* We note, however, that the American Declaration’s use, in its title and its terminology, of androcentric terms contrasts with the deliberately gender-neutral use of the term “everyone” in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, an unfortunate reminder of the discriminatory past.

* Although beyond the scope of this article, it should also be noted that national courts are increasingly rejecting “fetal rights” challenges to permissive abortion laws.Citation55Citation56Citation57Citation58Citation59Citation60Citation61Citation62Citation63Citation64 Although the German Criminal Court originally ruled that abortion should remain technically illegal, it also specified that there should be no prosecution of a woman who chooses abortion after counselling. The 1995 amendment permits abortion in the first 12 weeks of pregnancy after counselling or where pregnancy results from a crime such as rape, and at any time for a medical emergency. Citation65Citation66

* The work of the United Nations treaty bodies can be searched thematically at <www.bayefsky.com> and updated through reference to the treaty bodies on the UN website <www.un.org>.

References

- M Berer. National laws and unsafe abortion. the parameters of change. Reproductive Health Matters. 12(24 Suppl): 2004; 1–8.

- World Health Organization. Safe Abortion: Technical and Policy Guidance for Health Systems. 2003; WHO: Geneva.

- World Health Organization. Unsafe Abortion: Global and Regional Estimates of the Incidence of Unsafe Abortion and Associated Mortality in 2000. 2004; WHO: Geneva. Full references available at: <http//:www.who.int/reproductive-health/publications/unsafe_abortion_estimates_04/estimates.pdf. >.

- UN Population Division. Programme of Action of the International Conference on Population and Development, Report of the International Conference on Population and Development, Part I, Section 1, UN Doc. A/CONF.171/13, 1994.

- UN Population Division. Adoption of the Programme of Action, ICPD Report, Ch. V, Report of the International Conference on Population and Development, Part I, Section 1, UN Doc. A/CONF.171/13, 1994.

- Report of the United Nations World Population Conference, UN Sales No. E.75.XIII.3, 1974 and Report of the International Conference on Population, Mexico City, 6-14 August 1984 (UN publication, Sales No. E.84.XIII.8 and corrigenda).

- Vo v. France, App. No.53924/00, European Court of Human Rights, 8 July 2004.

- United Nations Universal Declaration on Human Rights, UN GAOR, Art.1, G.A. Res.217, UN Doc. A/810, 1948.

- UN GAOR 3rd Comm., 99th mtg. at 110-124, UN Doc. A/PV/99, 1948.

- UN GAOR 3rd Comm., 183rd mtg. at 119, UN Doc. A/PV/183, 1948.

- J Morsink. Women's rights in the Universal Declaration. Human Rights Quarterly. 13: 1991; 229–256.

- International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, 16 December 1966, 993 UNTS 171, entered into force 23 March 1976.

- UN GAOR Annex, 12th Session, Agenda Item 33, at 96, UN Doc. A/C.3/L.654.

- UN GAOR, 12th Session, Agenda Item 33, at 113 UN Doc. A/3764, 1957.

- UN GAOR, 12th Session, Agenda Item 33, at 119 (q), UN Doc. A/3764, 1957.

- Concluding Observations of the Human Rights Committee, UN Doc. CCPR/C/79/Add.104.

- Concluding Observations of the Human Rights Committe Chile, 30/3/1999, UN GAOR, Hum. Rts. Comm., 65th Session, 1740th mtg. Para.15e: Argentina, 15/11/2000, UN Doc. CCPR/CO/70/ARG, Para.14.

- Concluding Observations of the Human Rights Committee: Costa Rica, 08/04/99, UN Doc. CCPR/C/79/Add.107, Para.11.

- Concluding Observations of the Human Rights Committee: Peru.

- Concluding Observations of the Human Rights Committee: United Republic of Tanzania, 18/08/98, UN Doc. CCPR/C/79/Add.97, Para.15.

- Concluding Observations of the Human Rights Committee: Venezuela, 26/04/2001, UN Doc. CCPR/CO/71/VEN, Para.19.

- Concluding Observations of the Human Rights Committee: Poland, 05/11/2004, UN Doc. CCPR/CO/82/POL, Para.8.

- Concluding Observations of the Human Rights Committee: Bolivia, 05/05//97, UN Doc. CCPR/C/79/Add.74, Para.22.

- Concluding Observations of the Human Rights Committee: Colombia, 03/05/97, UN Doc. CCPR/C/79/Add.76, Para.24.

- Concluding Observations of the Human Rights Committee: Ecuador, 18/08/98, UN Doc. CCPR/C/79/Add.92, Para.11.

- Concluding Observations of the Human Rights Committee: Mongolia, 25/05/2000, UN Doc. CCPR/C/79/Add.120, Para.8(b).

- Concluding Observations of the Human Rights Committee: Poland, 29/07/99, UN Doc. CCPR/C/79/Add.110, Para.11.

- Concluding Observations of the Human Rights Committee: Senegal, 19/11/97, UN Doc. CCPR/C/79/Add 82, Para.12.

- Human Rights Commission, Gen Comment 28: Equality of Rights Between Men and Women (68th Session 2000) at Para.10, reprinted in Compilation of General Comments and General Recommendations Adopted by Human Rights Treaty Bodies, 12/05/2004, UN Doc. HRI/GEN/Rev.7.

- Convention on the Rights of the Child, GA Res. 44/25, Annex, UN GAOR 44th Session, Suppl. No.49 at 166, UN Doc. A/44/49 (1989) (entered into force Sept. 2, 1990).

- UN Commission on Human Rights, Question of a Convention on the Rights of a Child: Report of the Working Group, 36th Session, UN Doc. E/CN.4/L/1542 (1980).

- UN Commission on Human Rights, Report of the Working Group on a Draft Convention on the Rights of the Child, 45th Session, E/CN.4/1989/48 at p.10 (1989), quoted in Jude Ibegbu, Rights of the Unborn in International Law 145 (2000).

- LJ LeBlanc. The Convention on the Rights of the Child: United Nations Lawmaking on Human Rights. 1995; University of Nebraska Press: London, 69.

- J Ibegbu. Rights of the Unborn Child in International Law. 2000; E Mellen Press: Lewiston NY, 146–147.

- Committee on the Rights of the Child, General Comment No.4: Adolescent health and development in the context of the Convention on the Rights of the Child (33rd Session 2003) at Para. 31, reprinted in Compilation of General Comments and General Recommendations Adopted by Human Rights Treaty Bodies, 12/05/2004, UN Doc. HRI/GEN/Rev.7.

- Concluding Observations of the Committee on the Rights of the Child: Guatemala, 9/7/2001, UN Committee on the Rights of the Child, 27th Session, p.40, UN Doc. CRC/C/15/Add.154.

- Concluding Observations of the Committee on the Rights of the Child: Chad, 24/8/1999, UN GAOR, Committee on the Rights of the Child, 21st Session, 557th mtg. Para.30, UN Doc. CRC/C/15/Add.107.

- Concluding Observations of the Committee on the Rights of the Child: Nicaragua, 24/8/1999, UN GAOR, Committee on the Rights of the Child, 21st Session, 557th mtg. Para.35, UN Doc. CRC/C/15/Add.108.

- Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women, G.A. Res. 34/180 (18 December 1979).

- Committee on the Elimination of Discrimination against Women, General Recommendation 21: Equality in Marriage and Family Relations (13th Sess., 1994), in Compilation of General Comments and General Recommendations by Human Rights Treaty Bodies, at 253. Para. 14. UN Doc. HRI/GEN/1/Rev.7 (2004).

- Committee on the Elimination of Discrimination against Women, General Recommendation 24: Women and Health (20th Session, 1999), in Compilation of General Comments and General Recommendations by Human Rights Treaty Bodies, at 274, Para.14, U.N .Doc. HRI/GEN/1/Rev.7 (2004).

- Center for Reproductive Rights and University of Toronto International Programme on Reproductive and Sexual Health Law. Bringing Rights to Bear: An Analysis of the Work of the U.N. Treaty Monitoring Bodies on Reproductive and Sexual Rights, New York: CRR, 2002.

- European Convention on Human Rights and Fundamental Freedoms, 312 UNTS 221 (entered into force on 3 September 1953), as amended by protocols 4, 6, 7, 12 and 13 to the Convention.

- Committee on Legal and Administrative Questions Report, Section 1, Para.6, 5 September 1949, in Collected Edition of the Travaux Préparatoires, Vol. 1 (1975), p.194.

- Paton v. UK, App. No. 8317/78, European Commission on Human Rights, 13 May 1980, 3 European Human Rights Rep.408 (1981), (Commission report), also cited as X. v. UK.

- RH v. Norway, Decision on Admissibility, App. No.17004/90, 73 European Commission on Human Rights Dec. & Rep. 155 (19 May 1992).

- Boso v. Italy, App. No.50490/99, European Commission on Human Rights (September 2002). American Declaration, OAS Off. Rec. OEA/Ser.L/V/II.82, Doc.6, Rev.1(1948).

- American Declaration of Rights and Duties of Man, OAS Res. XXX, in Basic Documents Pertaining to Human Rights in the Inter-American System, OAS/Ser.L/V/I.4rev. 7 at 15 (2000).

- American Convention on Human Rights, OAS Off. Rec. OEA/Ser.L/V/II.23, Doc.21, Rev.6 (1969) at Art. 4, in Basic Documents Pertaining to Human Rights in the Inter-American System, OAS/Ser.L/V/I.4rev. 7 at 23 (2000).

- Baby Boy, Case 2141, Inter-American Convention on Human Rights 25/OEA/ser. L./V./II.54, Doc.9 Rev.1 (1981).

- Protocol to the African Charter on Human and Peoples' Rights on the Rights of Women in Africa, Art.14(2)(c), adopted by resolution AHG/Res. 240 (XXXI), 31st Sess. (11 July 2003).

- African Charter on Human and Peoples' Rights, OAU Doc. CAB/LEG/67/3 rev.5 (1981) (entered into force 21 October 1986).

- The Protocol on the Rights of Women in Africa: An Instrument for Advancing Reproductive and Sexual Rights, Center for Reproductive Rights, June 2005. At: . <http://www.reproductiverights.org/pdf/pub_bp_africa.pdf>.

- African Charter on the Rights and Welfare of the Child, Art. 5(1), OAU Doc. CAB/LEG/24.9/49 (1990) (entered into force 29 November 1999).

- Decision of the Constitutional Court of 11 October 1974, 39 Erkentnisse und Beschluesse des Verfassungsgerichthofes (1974), summarised in Annual Review of Population Law 1974;1:49.

- Conseil Constitutionnel: Décision n° 74-54 du 15 janvier 1975, Loi relative à l'interruption volontaire de la grossesse. At: . <http://www.conseil-constitutionnel.fr/decision/1974/7454dc.htm>. Accessed 15 February 2005.

- Juristenvereiniging Pro Vita v. De Staat der Nederlanden (1991), summarised in Annual Review of Population Law 1991;19( 5)179-80.

- The Conseil Constitutionnel: Décision n° 74-54 du 15 janvier 1975, Loi relative à l'interruption volontaire de la grossesse. At: <http://www.conseil-constitutionnel.fr/decision/1974/7454dc.htm. >. Accessed 15 February 2005.

- R. v. Morgentaler, 1 S.C.R. 30 (1988).

- R. v. Sullivan and Lemay, 1 S.C.R. 489 (1991).

- Winnipeg Child Family Services (Northwest Area) v. G.3 S.C.R. 925 (1997).

- Roe v. Wade, 410 U.S. 113, 163 (1973).

- Stenberg v. Carhart, 530 U.S. 914 (2000).

- Christian Lawyers Association of South Africa and Others v. Minister of Health and Others, 50 BMLR 241, 10 July 1998 (High Court of South Africa, Transvaal Provincial Division).

- German Embassy, Questions & Answers about Germany: Health Care, Health Issues and Social Welfare: Health Issues: Is Abortion Legal?. At: <http://www.germany-info.org/relaunch/info/facts/facts/questions_en/health/healthissues3.html. >. Accessed 14 February 2005.

- Will R. German unification and the reform of abortion Law. Cardozo Women's Law Journal 1996;3:399/422-23.

- B Babcock, A Freedman, S Ross. Sex Discrimination and the Law: History, Practice and Theory. 1976; Little, Brown & Co: New York.

- DH Regan. Rewriting Roe v. Wade. Michigan Law Review. 77: 1979; 1569.

- JJ Thompson. A defense of abortion. Philosophy and Public Affairs. 1: 1971; 47.

- R Smith. Rights, Duties, and the Body: Law and Ethics of Maternal-Fetal Conflict. 2002; Hart Publishing: Portland OR, 355.

- McFall v. Shimp, 10 Pa D. & C. 3d 90 (1978).