Abstract

This study analysed the relative contributions of three possible determinants to the high sex ratio among newborns in rural China – under-reporting of female births, abortions of female fetuses and excess early female neonatal mortality. A cohort of 3,697 pregnancies collected at village level in 20 rural townships from a county in Anhui province in 1999 was followed from pregnancy registration to seven days after birth. The cohort was later completed with 267 retroactively registered pregnancies. In the original cohort, the sex ratio at birth was 152 males to 100 females and in the supplemented cohort 159 males to 100 females, being similar to the sex ratios in the census data of the same townships. The risk of death for girls was almost three times that for boys during the first 24 hours of life. A comparison of the estimated number of missing girls by parity and pregnancy approval status to the recorded abortions and stillbirths suggests that selective abortions of female fetuses contributed most to the extremely high sex ratio among newborns. The under-reporting of female live births and neglect or poorer care of female newborn infants seemed to play a secondary role. New technology has helped the one-child policy to become, in practice, an “at-least-one-son” practice.

Résumé

Cette étude a analysé la contribution de trois facteurs pouvant expliquer le rapport de masculinité élevé chez les nouveau-nés en Chine rurale : sous-déclaration des naissances de filles, avortement des fétus féminins et mortalité néonatale féminine précoce excessive. Une cohorte de 3697 grossesses dans 20 agglomérations rurales d'un comté de la province d'Anhui en 1999 a été suivie depuis l'enregistrement de la grossesse jusqu'à sept jours après la naissance. La cohorte a été complétée par 267 grossesses enregistrées rétroactivement. Dans la cohorte originale, le rapport de masculinité à la naissance était de 152 garçons pour 100 filles et de 159 garçons pour 100 filles dans la cohorte complétée, semblable aux données du recensement pour les mêmes agglomérations. Pendant les 24 premières heures de vie, le risque de décès des filles est près de trois fois supérieur à celui des garçons. Une comparaison du déficit de filles par parité et statut d'approbation de la grossesse avec le nombre d'avortements enregistrés et d'enfants mort-nés suggère que l'avortement sélectif des fétus féminins a contribué à l'essentiel de la masculinité extrêmement élevée. La sous-déclaration des naissances vivantes de filles et le manque ou l'absence de soins aux nouveau-nés féminins semblent jouer un rôle secondaire. Les nouvelles technologies ont permis à la politique de l'enfant unique de devenir, dans la pratique, une politique « d'au moins un fils ».

Resumen

Este estudio analizó las contribuciones de tres determinantes a la alta tasa de proporción de sexos entre los recién nacidos en las zonas rurales de China: el de nacimientos de niñas, el aborto de fetos femeninos y el exceso de mortalidad neonatal de niñas. En 1999, se dio seguimiento a 3,697 embarazos en 20 municipalidades rurales en la provincia de Anhui, desde el registro del embarazo hasta siete días después del nacimiento. Se añadieron 267 embarazos registrados de manera retroactiva. En el grupo original, la proporción de sexos entre recién nacidos fue de 152 niños por cada 100 niñas y en el grupo complementado de 159 niños por cada 100 niñas, similar a las proporciones de sexos en los datos del censo de las mismas municipalidades. Durante las primeras 24 horas de vida, el riesgo de muerte de las niñas fue casi tres veces mayor que el de los niños. Al comparar el número aproximado de niñas que faltaban por paridad y aprobación del embarazo con los abortos y mortinatos registrados, se observó que el aborto selectivo de fetos femeninos fue el mayor contribuyente a la altísima proporción de sexos entre los recién nacidos. Aparentemente, el subreportaje de las niñas nacidas vivas y el descuido o cuidado inferior de las niñas recién nacidas desempeñó una función secundaria. Debido a la nueva tecnología, la política de un solo hijo ha pasado a ser práctica de “un hijo mínimo”.

Worldwide, the natural sex ratio at birth is around 106.Citation1Citation2Citation3 In China, the sex ratio at birth rose from 107 in 1981 to around 114 in 1993,Citation4 which generated concern among scholars and policymakers about the negative social, demographic and health consequences.Citation5Citation6 In the census of the year 2000, the reported sex ratio at birth for the whole country was 117 and for Anhui province 131.Citation7Citation8 The phenomenon of high sex ratio at birth and in infancy does not appear in China alone, but also in other Asian countries such as Singapore, South Korea and parts of northern India, which all have in common a declining fertility rate and a traditional preference for males.Citation2Citation3Citation9

The following three factors have been suggested as reasons for the increase in the reported sex ratio at birth and among infants: 1) under-reporting of female births (including children given away for adoption whose births were not reported), 2) antenatal sex determination and selective abortions of female fetuses, and 3) excess early female neonatal mortality. There has been no agreement on the relative contribution of these factors.Citation4Citation5Citation10Citation11Citation12Citation13Citation14 A recent extensive review of sex ratios in China, however, concluded that after widespread introduction of ultrasound screening technologies, both sex-selective abortion and infanticide of unwanted girls have existed side by side, both contributing to the problem of missing girls, while under-reporting has played a less significant role.Citation2 Strictly speaking, the sex ratio at birth is not affected by infanticide and neglect of female infant care, but when studying reported sex ratio at birth, many scholars have included them; studies have commonly used data from population censuses that rely on face-to-face interviews.Citation2Citation3Citation4Citation5Citation10Citation11Citation12Citation13 Data collected by such interviews may, however, be biased by the illegality of having many children, and of antenatal sex determination infanticide.Citation15 Past censuses are estimated to have undercounted children younger than six years of age by about 5%, girls more often than boys.Citation16

The purpose of this paper is to examine what happens to the sex ratio from birth to seven days of age and the relative contribution of the three factors mentioned above to the high sex ratio among newborn infants in a rural county of Anhui province, China, based on a community-based cohort of 3,697 pregnancies, following them from the first pregnancy registration to seven days after birth.

Context and background

Male preference is part of the old Confucian value system which has for centuries influenced family formation and childcare practices in China.Citation2 Under Confucian values, males were honoured over females to the extent that newborn girls were killed or died because of neglect or maltreatment. Even though the Republic of China tried to abolish these practices in the 1920s and the People's Republic outlawed them, the preference for males has remained strong in parts of China.Citation2

The Chinese government introduced the policy of one child per family in 1979 in order to reduce population growth.Citation17 However, due to the preference for male children, common particularly in rural areas, this strict regulation was modified in the mid-1980s in most provinces so that rural couples with a first-born girl child were allowed to have a second child.Citation18 Financial and other incentives have been used to encourage people to follow the policy regulations, and discouragement of larger families has included financial levies on each additional child as well as other sanctions.Citation19

Local family planning regulations have varied in their details, but even today everywhere in China the right to carry a pregnancy to term is dependent on approval by local family planning authorities, who commonly persuade parents to terminate all pregnancies not covered by family planning regulations and marriage laws. There is an extensive and well-organised network of family planning authorities at every level of government, down to the rural villages.Citation20

The county where this study took place is situated in eastern China in Anhui province and has a predominantly farming population of almost 900,000. Its national gross domestic product ranking is typical of less developed rural areas in China. Anhui province is one place in China where a strong preference for males has persisted in spite of political and economic changes.Citation2 At the time of the study, the local family planning regulations allowed married couples to have a second pregnancy four years after a female first-born child but not after a healthy male. Third pregnancies and higher parity were not approved. The local family planning system was performing according to the national standard: birth rate in the study county in 2000 was 10.3 per 1,000, which was a little lower than the average level for the whole province (11.2 per 1,000 in 2002) and lower than the national rate of 12.9 per 1,000 in 2002.Citation21Citation22

The family planning services in the study county were administratively divided into 55 townships, each responsible for 6–16 villages. Medically trained personnel, mainly midwives, were employed in the township family planning offices, and there were lay family planning workers at the village level. The village family planning workers provided free contraceptives, assisted in pregnancy testing and reported population events to township-level authorities. Whether a pregnancy was approved or not was decided jointly by the village and township family planning authorities, based on local regulations.

Mandatory pregnancy testing was done by township family planning staff every 2–3 months on all married women under the age of 50. The village family planning workers were present and recorded positive tests for follow-up. These records were copied by hand by the village family planning workers to township records in the monthly meetings between the village and township staff. Village family planning workers later informed the township family planning office of the outcome of each pregnancy (miscarriages, abortions, stillbirths, live births, neonatal deaths) with the appropriate date, and that information was added by village family planning workers to the already existing record of a positive pregnancy test. If no information of the outcome was provided by the village worker, township family planning staff actively asked for it. Pregnancies with the last date of menstruation, approval status, and women's identification were thus registered prospectively before birth, at the time the pregnancy was identified. If an unregistered birth occurred (rare according to the order of records), the pregnancy was registered only at the time of birth. Individual level vital registries were kept at the township level and summary tables were reported to the county level.

Ultrasound equipment for antenatal screening was commonly available in township hospitals; 17 out of 20 study township hospitals had such equipment before 1999. Private medical services were also commonly available both at village and township levels. These were officially not allowed to be involved in pregnancy or birth care, but women did have access to antenatal screening at private clinics too.

Subjects and methods

The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the National Research and Development Centre for Welfare and Health (STAKES) in Helsinki on 11 January 1999. This was a cohort study based on the records of pregnancies registered by village level family planning authorities (n=3,697) in 1999 between 1 January–31 December in 20 selected townships in the county studied. This was the original cohort. The data were collected in late 2000 as pre-intervention data for a controlled trial of the introduction of systematic antenatal care in rural China. The townships were selected on the basis that they had sufficient health facilities and staff to implement the trial.Citation21

The data on pregnancies and their outcomes were collected from the original family planning records in the study townships by a trained, local field research assisstant. The handwritten records, organised by the date of positive pregnancy test, included individual-level data on all women who had had a positive pregnancy test result.

The data extracted were: the woman's age (as recorded at the time of pregnancy registration), township of residence, number of living children, date of last menstrual period, approval status of the pregnancy, date of birth or spontaneous or induced abortion, offspring's date of birth, sex, plurality, birth order, live birth, stillbirth and early neonatal death. The sex of stillborns was not recorded. The number of living children at the time of pregnancy registration was used as parity data. Pregnancy duration was determined from the date of the last menstrual period and expressed in completed weeks. Stillbirth was defined as fetal death between 28 weeks of gestation and delivery. The period from birth to seven days of life was considered the early neonatal period.

In early 2004 the local research assistant also went back to the original family planning records of the 20 study townships to examine whether any new births had retroactively been recorded in the pregnancy records of 1999. A total of 267 previously unreported pregnancies and their outcomes were found to have been entered in the study township family planning records. Data on these 267 pregnancies were additional to data on the original cohort and together with the original data formed the supplemented cohort.

In 2000, a nationwide population census was carried out in China.Citation7 The census data were collected during the period 1 November 1999 to 31 October 2000, counting the number of men and women by age and locality. In 2004 we gained access to the census data of the study county (aggregated by township) and the region. The region consisted of the study county and three other counties and three cities. Using the raw census data, we calculated the sex ratios at birth, for under-one year-olds, 1–4 year-olds and 5-9 year-olds.

Relative risks and their confidence intervalsCitation23 were calculated for comparison between groups of different parity, pregnancy approval status and infant sex. Sex ratio at birth was calculated as the number of live male births to 100 live female births and sex ratio at other points in time as number of live males to 100 live females.

Results

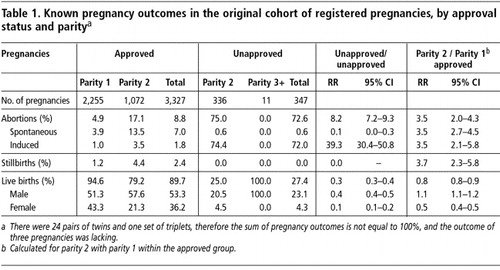

In the original cohort, approval status was a significant determinant of pregnancy outcome; 90% of approved pregnancies ended in a live birth while 73% of unapproved ones were aborted (Table 1). Among approved pregnancies, 80% of abortions were registered as spontaneous, but among unapproved, 99% of abortions were registered as induced. Stillbirths were significantly more common in second than in first pregnancies, but they appeared only among approved pregnancies.

Table 1 Known pregnancy outcomes in the original cohort of registered pregnancies, by approval status and paritya

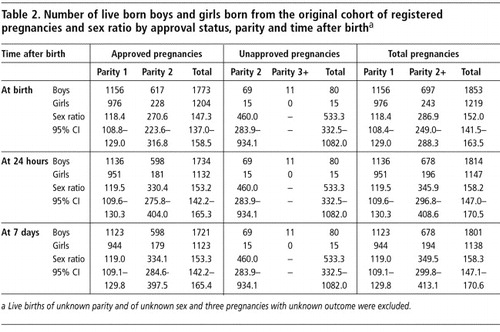

The total sex ratio at birth in the cohort was 152 males to 100 females, with 118 and 287 in first and second pregnancies respectively (Table 2). Among unapproved pregnancies, there were almost five live born boys for each girl. However, because these births only accounted for 3% of the live births, the sex ratio at birth in second pregnancies was determined mostly by the approved pregnancies. Within 24 hours, the sex ratio rose to 158 and remained almost unchanged until the seventh day of life.

Table 2 Number of live born boys and girls born from the original cohort of registered pregnancies and sex ratio approval status, parity and time after birtha

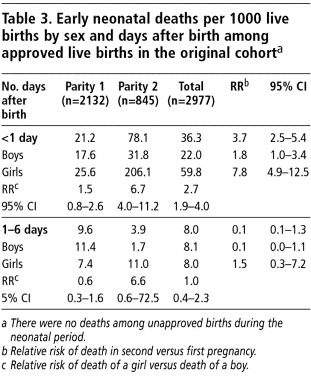

Most early neonatal deaths (82%) happened within 24 hours after birth, and during that time, girls were almost three times more likely to die than boys (Table 3). The death rate of females on the day of birth increased much more sharply with parity than that of males. Girls born from second pregnancies were almost seven times more likely to die on their day of birth than boys, while there was no significant difference in the death rates of first-born girls and boys. At 1–6 days after birth, the death rates of girls and boys did not differ in first or in second pregnancies.

Table 3 Early neontal deaths per 1000 live births by sex and days after birth among approved live births in the original cohorta

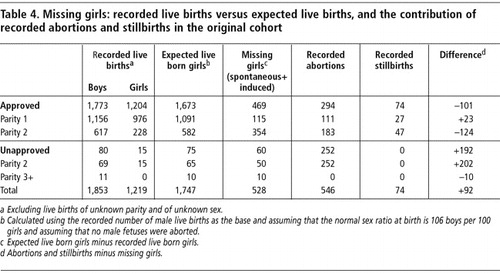

To estimate the potential contribution of different reasons for the high sex ratios at birth and early neonatal period, we calculated the hypothetical number of missing girls in the original cohort (Table 4). Assuming the normal sex ratio at birth to be 106 males for 100 females,Citation1 the original cohort of pregnancies that produced 1,853 boys (only women of known parity included) should have produced 1,747 girls; however, 528 fewer girls were actually born. Most often, females were missing in the group of approved second pregnancies. In that group, as opposed to other groups, the total number of recorded abortions was less than that of missing female infants.

Table 4 Missing girls: recorded live births versus expected live births, and the contribution of recorded abortions and stillbirths in the original cohort

In the 267 pregnancies entered into the family planning records of 1999 retroactively, there were 251 live births, 189 boys and 62 girls, a higher sex ratio (305 to 100) than in the original cohort. Similar to the original cohort the sex ratio reflected the pregnancy approval status, being 421 to 100 among unapproved (n=125) and 232 to 100 among approved pregnancies (n=126). When the known additional live births were added to the original cohort the sex ratio rose to 159 to 100 at birth and 166 to 100 at seven days after birth. The estimated number of missing girls at birth in the supplemented cohort was 645.

According to the 2000 census data, 2,057 male and 1,256 female infants (total = 3,313) were born in the study townships, giving a sex ratio of 164 to 100 at birth. The sex ratio increased to 172 at 0 age and decreased to 138 among 1–4 year olds and 123 among 5–9 year olds. Almost all these sex ratios were higher than the county and region level ratios for same age groups: 162, 167, 145 and 124 for age at birth, 0, 1–4 and 5–9 in the county and 128, 130, 126 and 117 in the region. The census found 154 more births in study townships than were registered in the supplemented cohort.

Discussion

This was the first community-based cohort study in China to use data collected routinely by the family planning system at village level. The chosen data source proved effective in following up the registered pregnancies to their outcomes, as only in three out of 3,697 cases were the outcome data missing. In China, where family planning policy and its implementation are given top priority at all levels, pregnancy data collection is also prioritised.Citation21 The age and parity distribution of the study cohort reflected the marriage law and family planning policy restrictions on childbearing. Most registered second pregnancies occurred within the regulated circumstances, and third pregnancies were very rare. But our data clearly show that many aborted pregnancies were not registered. Either parents managed to hide the pregnancy from the village family planning worker or the family planning workers agreed not to register pregnancies that were terminated.

High numbers of induced abortions show unsuccessful family planning, and there was a disincentive to register. Because the village family planning worker was responsible for a population of 1,000 on average in a relatively small area, she would generally be aware of pregnancies among them. Married women staying outside of their home villages for longer periods of time were required to mail back family planning certificates of pregnancy testing regularly. The control system was comprehensiveCitation21 and it is likely that non-registration was a joint decision of the parents and the family planning workers. Some of the induced abortions may have been labelled as miscarriages or stillbirths, which would perhaps partially explain the increase in miscarriages by parity.

The sex ratio at birth in both study townships (163.8) and study county (161.7) was much higher than the average for the whole province (130.8).Citation8 That the census found 154 more births in study townships than were registered in the supplemented cohort might be due to the different way and time span in which the data were collected: for the cohort data in 1999, the family planning staff had followed the 3,697 pregnancies to term. On average, the time from pregnancy detection and registration to birth was about 37 weeks. So the births of the cohort started occurring earlier than October 1999 and continued through to September 2000. The number of live births in the census was collected from 1 November 1999 to 31 October 2000.

Many fewer girls than boys were born and far fewer girls than boys survived to seven days of age in the original cohort. The high sex ratios among newborns were verified by the year 2000 census data from the same townships. To have such a high sex ratio among newborns may result either from an excess of female fetuses among registered or unregistered abortions, miscarriages or stillbirths or from female live births being missed or hidden from registration. What is the likelihood of these explanations of the high sex ratio at birth and at seven days of age?

The parents' interest in knowing the sex of the fetus and willingness to selectively abort females was likely to have been linked to the approval status of the pregnancy. Therefore it is useful to examine the approved and unapproved pregnancies separately with regards to the likelihood of selective abortions. Among unapproved second pregnancies there were more than twice as many abortions than the estimated number of missing girls, so all of them could possibly have been explained by the recorded abortions. Among approved pregnancies, the number of recorded abortions was less than the number of estimated missing girls. However, in our estimation potentially the largest group of missing girls in the original cohort was among the approved second pregnancies. Even if all the recorded abortions and stillbirths had been girls, all missing girls would not be covered, which implies that a considerable number of pregnancies were not registered. Those parents with one female child could have chosen not to register a pregnancy before knowing the sex of the fetus, and to selectively abort a female fetus in order to secure another legal chance to have a son. If the sex determination was done in the private sector before pregnancy registration, the parents could keep both the pregnancy and its termination hidden from the family planning authorities. It is likely that a large part of the missing girls in the approved pregnancies were aborted without registering.

If pregnancies were hidden to term or even longer, through adoption or staying outside the home village, they were not registered by family planning staff into the original cohort. Pregnancies of women who had a temporary residence elsewhere were registered upon the mother's return to the home village. Among the late registrations, there were both approved and unapproved pregnancies, but 70% of the 251 live births were male. This result did not support the hypothesis that under-reporting female live births was a major determinant of the high sex ratio at birth although some, mostly female, births might have remained undetected due to abandonment or adoption.Citation24Citation25

The third possible influence on high sex ratios was neglect or infanticide of newborn girls. Without human intervention, boys have a higher early neonatal mortality than girls.Citation26Citation27 The result of our original cohort study was the opposite, which would indicate that neglect or infanticide might have played a role. Further, given that stillbirths were confined to registered and approved pregnancies, among stillbirths there may have been further cases of live born girls dying shortly after birth being misclassified as stillbirths. The higher female mortality might have been due to poorer care and less interest in seeking medical help in case of need.Citation6Citation6Citation11Citation28

The sex ratio at birth (152) and at seven days after birth (158) determined in this study were higher than previously reported ratios in ChinaCitation4Citation5Citation6Citation10Citation11Citation12, and also higher than the most recent national ratio (117) from the population census of 2000.Citation7 However, sex ratios of our supplemented cohort (those born in 1999 and 2000, at birth and seven days after birth) corresponded reasonably well with those of the census data (at birth and up to one year old in 2000) of the same townships. National calculations of census coverage estimate that 2% of the population was missed.Citation29 According to the census data, the sex ratio declined by age, especially in the study county. This may indicate that selective abortions had increased in the area in the latter half of the 1990s or that live born females missed from registration at birth in previous age cohorts were registered at an older age than males.

The possible scenarios leading to the high sex ratio at birth and among newborn infants discussed here are based on the assumption that the cultural and economic preference for boys is prevalent in the study county, as has been shown in Anhui province and elsewhere in rural China,Citation2Citation6Citation17Citation30Citation31 and that this preference in the context of strict enforcement of the family planning policy would guide the parents to seek for knowledge of the sex of the fetus antenatally and even before pregnancy registration. These practices are of course very difficult to prove due to their illegality. The use of medical technology for antenatal sex determination has been strictly forbidden in China since 1989Citation32 and sex-selective abortions were outlawed in 1994.Citation33 Enforcement of the regulations has, however, proven difficult. Screening for fetal sex is widely practiced in China, even in rural areas.Citation34Citation35 In the study townships, ultrasound equipment was widely available both in the public and private health services, and it was no doubt used also for sex determination. Furthermore, due to severe public under-funding and dependence on user fees,Citation36 rural health service providers might be tempted to offer illegal fetal sex determination services in order to be competitive.

In summary, the selective abortion of female fetuses was likely to contribute most to the high sex ratio found in the cohort. The outcome of the original cohort also suggests neglect or poorer care of female newborn infants because the sex ratio somewhat increased during the first 24 hours of life. The under-reporting of female births played a secondary role. In light of these findings the one-child policy seems to have, in the context of declining fertility and continuing economic and cultural preference for males, become an “at-least-one-son” practice in rural China. This is in congruence with the analysis of the development and determinants of historically reported sex ratios.Citation2 Falling family size has also in other Asian regions exacerbated the effects of cultural son preference, as has been seen in Hong Kong, Taiwan, Singapore and Korea.Citation2Citation9 In China the one-child family planning policy has played an important role in focusing the cultural demand for a son to the few legal reproduction events.

However, the potentially disastrous social consequences of the distorted sex ratios among young age cohorts have already been acknowledged by the Chinese Government. The scarcity of females has resulted in young men having difficulty finding someone to marry, in kidnapping and trafficking of women for marriage, and in increased numbers of commercial sex workers, with the potential for a rise in HIV infection and other sexually transmitted diseases, among other negative consequences. There are fears that these consequences could be a real threat to China's stability in future.Citation9 Assumptions that discrimination against girls would diminish with economic development and female education have proven simplistic.Citation36 Laws banning fetal sex determination before birth have clearly not been enough to stop discrimination against females. To overcome the effects of male preference special promotion of girls' and women's rights is needed. Such action could be, for instance, to develop specific social and economic policies to protect the basic rights of girl children, and to promote the principle of true equality between men and women.

Acknowledgements

We thank Ms Haifeng Xu for her assistance in data collection. This study was financially supported by a grant from the Academy of Finland.

References

- DL Davis, MB Gottlieb, JR Stampnitzky. Reduced ratio of male to female births in several industrial countries. JAMA. 279: 1998; 1018–1023.

- J Banister. Shortage of girls in China today. Journal of Population Research. 21: 2004; 19–45.

- Y Zeng, P Tu, B Gu. Causes and implications of the recent increase in the reported sex ratio at birth in China. Population and Development Review. 19: 1993; 283–302.

- BC Gu, K Roy. [Comparison of unbalanced sex ratios between South Korea, Taiwan and Mainland China (in Chinese)]. Population Research. 20: 1996; 1–15.

- SZ Li, CZ Zhu. [Sex ratio at birth and infant living status in China (in Chinese)]. Population and Economics. 1: 1996; 13–18.

- T Hesketh, WX Zhu. The one child policy: the good, the bad, and the ugly. BMJ. 314: 1997; 1685.

- T Plafker. Sex selection in China sees 117 boys born for every 100 girls. BMJ. 324: 2002; 1233.

- YX Sun. [Review of abnormal sex ratio at birth in China (in Chinese)]. Journal of Nanchang Institute of Aeronautical Technology (Social Science). 5: 2003; 114–116.

- T Hesketh, L Li, WX Zhu. The effect of China's one-child family policy after 25 years. New England Journal of Medicine. 353: 2005; 1171–1176.

- TH Hull. Recent trends in sex ratios at birth in China. Population and Development Review. 16: 1990; 63–68.

- S Johansson, O Nygren. The missing girls of China: a new demographic account. Population and Development Review. 17: 1991; 35–51.

- P Tu. [Exploration of sex ratio at birth in China (in Chinese)]. Population Research. 1: 1993; 6–13.

- MG Merli, AE Raftery. Are births underreported in rural China? Manipulation of statistical records in response to China's population policies. Demography. 37: 2000; 109–126.

- Q Wang, H Wang. [SFPC special survey in Hubei and Heibei provinces (in Chinese)]. Population Research. 19: 1995; 27–29.

- E Hemminki, ZC Wu, GY Cao. Illegal birth and legal abortions – the case of China. Reproductive Health. 2: 2005; 5.

- D Walfish. A billion and counting: China's tricky census. Science. 290: 2000; 1288–1289.

- P Kane, CY Choi. China's one child family policy. BMJ. 319: 1999; 992–994.

- D Payne. China moves to change policy on child quotas. BMJ. 316: 1998; 959.

- J Bernman. China attempts to soften its one-child policy. Lancet. 353: 1999; 567.

- BL Xiao, BG Zhao. Current practice of family planning in China. International Journal of Gynecology and Obstetrics. 58: 1997; 59–67.

- ZC Wu, K Viisainen, Y Wang. Perinatal mortality in rural China. British Medical Journal. 327: 2003; 1319–1322.

- J Wu. [China's population in 2002. Almanac of China's Population, 2003 (in Chinese)]. Institute of Population and Labour Economics, China Academy of Social Science. 2003; Almanac of China's Population Press: Beijing, 83–89.

- MJ Gardner, DG Altman. Statistics with Confidence - Confidence Intervals and Statistical Guidelines. 1989; BMJ: London.

- K Johnson. The politics of infant abandonment in China. Population and Development Review. 22: 1996; 77–98.

- K Johnson, B Huang, L Wang. Infant abandonment and adoption in China. Population and Development Review. 24: 1998; 469–510.

- P Karlberg, A Ericson. Perinatal mortality in Sweden. Analyses with international aspects. Acta Paediatrica Scandinavica. 275(Suppl): 1979; 28–34.

- J Zhang, WW Cai, H Chen. Perinatal mortality in Shanghai: 1986–1987. International Journal of Epidemiology. 20: 1991; 958–963.

- SZ Li, CZ Zhu, MW Feldman. Gender differences in child survival in contemporary rural China: a county study. Journal of Biosocial Science. 36: 2004; 83–109.

- H Cui, W Zhang. Preliminary evaluation of population size by the 2000 national population census. Population Research. 26: 2002; 23–27.

- JP Doherty, EC Norton, JE Veney. China's one-child policy: the economic choices and consequences faced by pregnant women. Social Science and Medicine. 52: 2001; 745–761.

- J Li. Gender inequality, family planning, and maternal and child care in a rural Chinese county. Social Science and Medicine. 59: 2004; 695–708.

- L Bogg. Family planning in China: out of control?. American Journal of Public Health. 88: 1998; 649–651.

- [Maternal and Child Health Care Law of the People's Republic of China (editorial, in Chinese]). Henan Zhengbao. 12: 1994; 3–6.

- JH Chu. Prenatal sex determination and sex-selective abortion in rural central China. Population and Development Review. 27: 2001; 259–281.

- G Bloom, SL Tang. Rural health pre-payment schemes in China: towards a more active role for government. Social Science and Medicine. 48: 1999; 951–961.

- P Löfstedt, SS Luo, A Johansson. Abortion patterns and reported sex ratios at birth in rural Yunnan, China. Reproductive Health Matters. 12: 2004; 86–95.