Abstract

This paper discusses the implications of shortages of midwives, nurses and doctors for maternal health and health services in sub-Saharan Africa, and inequitable distribution of maternal health professionals between geographic areas and health facilities. Shortages of health professionals reduce the number of facilities equipped to offer emergency obstetric care 24 hours a day, and are significantly related to quality of care and maternal mortality rates. Some countries are experiencing depletion of their workforces due to emigration and HIV-related illness. Another feature is the movement from public to private health facilities, and to international health and development organisations. The availability of skilled birth attendants and emergency obstetric care may be reduced due to understaffing, particularly in rural, poor areas. The existing workforce may experience increased workloads and job dissatisfaction, and may have to undertake tasks for which they are not trained. If governments and development partners are serious about reaching the Millennium Development Goal on maternal health, substantial numbers of professionals with midwifery skills will be needed. Shortages of maternal health professionals should be addressed within overall human resources policy. A rethink of health sector reforms and macro-economic development policies is called for, to focus on equity and strengthening the role of the state.

Résumé

Cet article examine les conséquences du manque de sages-femmes, d'infirmières et de médecins pour les services de santé maternelle et de santé en Afrique sub-saharienne, et la répartition inégale des professionnels de santé maternelle entre zones géographiques et centres de santé. Ces pénuries réduisent le nombre d'installations capables d'offrir des soins obstétriques d'urgence 24 heures sur 24, et influent sur la qualité des soins et les taux de mortalité maternelle. Dans certains pays, la main-d'éuvre est appauvrie par l'émigration et les maladies liées au VIH. Une autre caractéristique est le mouvement du public vers le privé, et vers les organisations internationales de santé et de développement. Ce phénomène peut réduire la disponibilité d'accoucheuses formées et de soins obstétriques d'urgence, particulièrement dans les zones rurales pauvres. Le personnel connaît donc un surcroît de travail, ce qui crée un mécontentement, et doit parfois accomplir des tâches pour lesquels il n'a pas été formé. Si les gouvernements et les partenaires de développement veulent vraiment atteindre l'objectif du Millénaire pour le développement en matière de santé maternelle, il leur faudra former un nombre substantiel de professionnels en obstétrique. Les pénuries de personnel de santé maternelle doivent être corrigées dans le cadre de la politique globale des ressources humaines. Il convient de repenser les réformes du secteur de la santé et les politiques de développement macro-économique, afin de se centrer sur l'équité et renforcer le rôle de l'État.

Resumen

Este artículo trata de la escasez de obstetrices, enfermeras y médicos en salud materna y servicios de salud general en África sub-Sahariana, y la distribución no equitativa de profesionales de la salud materna entre zonas geográficas y los establecimientos de salud. La escasez de estos profesionales disminuye el número de establecimientos equipados para ofrecer cuidados obstétricos de emergencia las 24 horas del día y está relacionada en gran medida con la calidad de la atención y las tasas de mortalidad materna. Algunos países están experimentando una reducción de su población activa debido a la emigración y las enfermedades relacionadas con el VIH. Otro aspecto es la mudanza del sector público hacia el privado, y a las organizaciones de salud y desarrollo internacional. La disponibilidad de parteras capacitadas y de cuidados obstétricos de emergencia podría reducirse debido a la falta de personal, particularmente en las zonas rurales pobres. La actual población activa podría experimentar mayores cargas de trabajo e insatisfacción en el trabajo, y verse obligada a realizar tareas para las cuales no está capacitada. Si los gobiernos y los colaboradores de desarrollo están verdaderamente comprometidos a lograr el Objetivo de Desarrollo para el Milenio respecto a la salud materna, se necesitarán muchos profesionales con habilidades en obstetricia. La escasez aquí mencionada debe tratarse como parte de la política general de recursos humanos. Para garantizar equidad y fortalecer la función del Estado, será necesario reformular las reformas del sector salud y las políticas de desarrollo macroeconómico.

Sub-Saharan Africa continues to be the region with the greatest burden of maternal ill-health. Although the uncertainty associated with reliably measuring maternal mortality makes identification of trends and cross-country comparisons within sub-Saharan Africa difficult,Citation1 absolute levels remain high compared to other regions, ranging from around 24 (Mauritius) to 2,000 (Sierra Leone) maternal deaths to 100,000 live births.Citation2

The causes of maternal mortality and morbidity are well known, and mainly result from the inability of a health system to deal effectively with complications, especially during or shortly after childbirth.Citation3 The availability of skilled health providers (particularly midwives, nurses, doctors and obstetricians) is critical in assuring high-quality antenatal, delivery, emergency obstetric and post-natal services. Indeed, the Millennium Development Goal for maternal health is unlikely to be achieved without attention to the recruitment and retention of health professionals.Citation4

This paper focuses on sub-Saharan Africa, a region with a large burden of maternal ill-health, where the workforce situation is considered to be in crisis.Citation5 A systems view of workforce issues is taken, especially in relation to the potential to use innovative policy and management approaches to address problems. The paper also considers how HIV/AIDS and economic circumstances make the “brain drain” damaging, and some of the wider development policy and macro-economic forces affecting human resources for health care.

First, the evidence for current shortages and maldistribution of maternal health professionals is reviewed, with the role of international migration highlighted. Second, the paper considers how shortages of health professionals might affect maternal health through two inter-related processes: effects on the existing workforce and effects on maternal health care. The paper concludes by discussing actions needed to better manage human resources to ensure women (particularly in rural, poor areas) have access to good quality maternal health care. The paper also indicates how such shortages have wider implications for reproductive health care, including family planning, sexually transmitted infections and HIV/AIDS.

Evidence was obtained from searches in bibliographic databases, reports and unpublished papers, websites and enquiries to international experts. As the search concentrated on the English language literature, the evidence presented may over-represent Anglophone African countries. The authors also draw upon their experiences of health systems research, consultancy and teaching, and learning from African health professionals taking postgraduate degrees at the Nuffield Centre for International Health and Development, University of Leeds (UK).

Workforce issues in maternal health: shortages, maldistribution, migration and HIV/AIDS

Health workforce issues in sub-Saharan Africa have received much attention recently,Citation5Citation6Citation7 and the literature is reviewed here briefly, with a focus on maternal health service providers. The completeness, disaggregated detail and comparability of data on human resources numbers and flows in this region present difficulties for determining patterns and trends.Citation8 Identifying shortages also requires estimating workforce skill mix, distribution and patient–professional staffing norms, which are subject to debate.Citation5 “Shortage” is a relative term: the USA with a ratio of 773 nurses per 100,000 population reports a nursing shortage, as does Uganda, with a ratio of 6 nurses per 100,000 population.Citation6

Estimates of how many additional doctors, nurses and midwives are needed in sub-Saharan Africa to provide essential health interventions related to the Millennium Development Goals range from 1–1.4 million.Citation5Citation9 Projecting future needs, WHO estimated that substantial shortages of professionals with midwifery skills need filling in sub-Saharan Africa to scale-up to universal coverage for maternal, newborn and child health.Citation3 One study estimated that from 2002 levels, the number of staff in Tanzania would have to double by 2007 and triple by 2015, while in Chad, the numbers would have to increase nine times by 2015.Citation10 The largest gaps between requirements and availability of staff were for nurses and midwives.

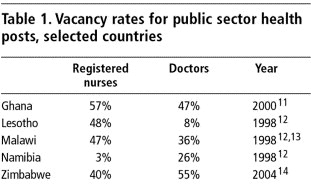

Vacancy rates in posts related to maternal health services would give another measure of shortages, but few published estimates were found (and may not even be available in health ministries). The lack of such data hinders planning for the education, recruitment and placement of these workers. Some vacancy rates for all health posts in the public sector are available (Table 1), although they should be interpreted cautiously, as they reflect the constraints on the health systems (including economic constraints) rather than health needs, and are not specific to maternal health.Citation6

Why do these shortages exist? The number of working maternal health professionals in a country's public health sector at any time will be affected by:

| • | inflows from training, immigration and employment in other sectors | ||||

| • | employment status: employed, unemployed or economically inactive | ||||

| • | outflows from death, disability, retirement, emigration, or to employment in other sectors. | ||||

The Citation12Citation13Citation14Citation17relative importance of these factors will vary by health system and geographic area, and over time. One inflow issue highlighted in international comparisons is the training of skilled birth attendants. In some African (and other) countries, midwifery is the only qualification required; in others, an additional year or two of midwifery training is routinely taken after a nursing qualification, with a higher commensurate salary.Citation7 However, many nurse–midwives subsequently work in nursing positions rather than midwifery positions. The financial and opportunity costs for training differ considerably under these two models, yet evidence to support decisions on the optimal duration and content of pre-service training is weak.Citation3

Two factors are depleting the number of health professionals in sub-Saharan Africa, HIV/AIDS and emigration. Ill-health due to HIV/AIDS in health workers is greatest in African countries with the highest adult HIV prevalence rates. Emigration has accelerated recently in countries such as Malawi, Nigeria, Swaziland, Zambia and Zimbabwe. Between 1998/99 and 2003/04, for example, the number of nurse–midwives from Ghana registering to work in the UK increased from 40 to 354; nurse–midwives from Zambia increased from 15 to 169, and nurse–midwives from South Africa from 599 to 1689.Citation15 To put these figures into context, the number of registered nurses graduating in these countries was 257 in Ghana (2002),Citation7 220 in Zambia (2003),Citation7) and 1,538 in South Africa (2002).Citation16Footnote1

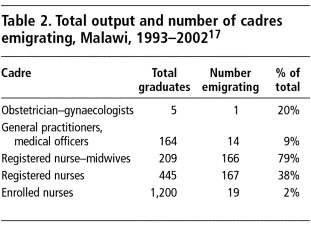

The impact of emigration is affected by the size of the existing workforce and inflows (training and immigration) of professionals into the health system. Countries with relatively small workforces and inflows, like Malawi (Table 2), can be disproportionately affected by outward flows. Table 2 indicates another feature evident in the literature: the more qualified maternal health staff are more likely to seek employment internationally.

The Citation17distribution of staff between geographic areas and health facilities is as important as total numbers of maternal health professionals, however. A higher ratio of health professional to population in urban and richer areas, and in tertiary care facilities, is a general pattern, with associated under-staffing in rural, poor locations, and in primary health care facilities.Citation6Citation7Citation18 Primary health care facilities are more accessible than hospitals for the majority of the population, being more numerous and widely distributed, and cheaper to use. They are usually staffed by nurses and midwives, who provide basic maternity care and referral to higher level facilities, along with other key mortality-preventing services such as family planning and (in some contexts) safe abortion.

Another feature in some African countries is the movement of health professionals from public to private (for-profit or not-for-profit) facilities,Citation19 and to international development, health and research organisations.Citation20 The impact on maternal health of movement from the public to the private sector will vary, depending on what services private providers offer, and their location, cost, and linkages with other health care. Evidence from South Africa suggests that over-medicalisation among private general practitioners (e.g. high caesarean section rates) may be a problem, but higher quality antenatal care was also found.Citation19 Given that 75% of South African specialists work in the private sector, a question is raised about the quality of services available for women delivering in the public sector.

The reasons why maternal health professionals are emigrating from sub-Saharan Africa are well known.Citation20Citation21 Inter-related employment gradients along which “push” and “pull” factors operate include:

| • | salary, social security and benefits | ||||

| • | job satisfaction | ||||

| • | organisational environment and career opportunities, and | ||||

| • | availability of resources (infrastructure, equipment and supplies).Citation11 | ||||

These gradients operate within a political, economic and socio-cultural context. War, civil unrest and economic deterioration can be “push” factors (for example, the recent outflow of Zimbabwean health professionals).Citation22 One factor whose effect is more uncertain is international funding. Development policy emphases since the 1990s on economic stability and adjustments and health sector reforms, privatisation, user-fee payment systems, and workforce downsizing have coincided with increased emigration of health professionals. These policy shifts have paid insufficient attention to human resources issues, and have helped to undermine health worker morale and the public service ethos, with serious results for health systems,Citation19 leading to calls for a more explicit assessment of the human resources impact of reforms.Citation23

Has HIV/AIDS affected emigration? In sub-Saharan African countries with a high HIV prevalence, perceived risk of occupational HIV infection over and above personal risk can be substantial, and usually is greater than actual risk.Citation20Citation24 It is unknown whether this high perceived risk, together with the contact with blood and body fluids during childbirth, may make midwifery a less popular profession, deter professionals from assisting in deliveries or fuel intentions to migrate to lower HIV prevalence working environments.Citation7

However, the pandemic does have other, clear effects. A large proportion of health workers are living with HIV/AIDS, 18–41% in many sub-Saharan countries.Citation25 Absenteeism resulting from burnout due to the excessive workload related to HIV/AIDS can be substantial.Citation6 In maternity care, this is due to dramatic increases in AIDS-related maternal illness and deaths from both direct (e.g. obstetric complications) and indirect causes (e.g. malaria, tuberculosis).Citation26 The need to upscale antiretroviral treatment can pull staff away from core services such as maternal health, and away from public services into non-governmental organisations, which provide the bulk of antiretroviral programmes. Overall, the increased need for antiretroviral treatment and for intensified care for pregnant women with HIV/AIDS-related illnesses, coupled with a reduced ability to provide such care, in a context where health professionals are emigrating, moving to the private sector, caring for family members with HIV/AIDS or themselves falling ill, place enormous strains on the health systems, including maternal health services.

Implications of shortages of health professionals for maternal health

What is the relationship between staffing levels, other human resources issues, access to services, quality of maternal health care and maternal health outcomes? The lack of evidence to connect these topics, especially from low-income countries, makes this difficult to answer.

A regression analysis of data for 117 countries found that doctor, nurse and midwife densities were significantly related to maternal mortality rates, when per capita income, female literacy and absolute poverty were controlled for.Citation27 Having an appropriate skill mix and team working for safe delivery are also suggested as important factors in reducing maternal mortality. Epidemiological data have shown that the proportion of births conducted by doctors versus midwives is a “powerful correlate of maternal mortality, emphasising the importance of partnerships between providers” (p.124).Citation28 Rather than simply focusing on whether there are skilled attendants (usually midwives) for all deliveries, these findings suggest it is also important to emphasise the accessibility of emergency obstetric care (provided mainly by doctors). It is important to note, however, that multivariate analyses are weakened by various unmeasured factors; for example, a professional qualification does not necessarily mean the provider is actually skilled, and the environment in which the professional is working may or may not be enabling, i.e. with adequate infrastructure, drugs and equipment.

Although such national-level multivariate analyses do not demonstrate causal mechanisms, two types of inter-related effects through which staff shortages may affect maternal health care and outcomes are suggested:

| • | effects on the existing workforce, caused by the “push” factors associated with staff attrition, and | ||||

| • | effects on maternal health care, including restricted availability of and access to services, and reduced volume and quality of services. | ||||

Effects of staff shortages on the existing workforce

“Many basic health facilities do not even have a midwife, so patients all come to the (tertiary) hospital and the workload has increased in the past years. You see the midwives sweating away; they cannot even have a cup of tea.” (Principal Nursing Officer, tertiary hospital, The Gambia)Citation29

Health professionals place considerable importance on the satisfaction they derive from providing good quality care, an intrinsic motivator to perform well and a strong determinant of overall patient satisfaction with care.Citation30 Working in an environment of under-staffing and attrition can reduce job satisfaction. Opportunities for collegial interaction and support, identified as contributing to job satisfaction, are restricted.Citation31 Teamwork is an essential component of high quality maternal health care, and loss of team members can also reduce job satisfaction and lower morale.Citation32 With increasing workload and changing role expectations, levels of stress, fatigue and emotional exhaustion can increase, all of which compromise both quality and safety of care. Staff may need to work unpaid overtime to complete work to the level they are satisfied with. Less flexibility is available to take paid or unpaid leave, or to participate in staff development and training activities, with effects on both quality of care and opportunities for career development.Citation33 A continued inability to provide quality care can contribute to job dissatisfaction, stress, demotivation and intentions to seek other employment, creating a vicious cycle of staff attrition.

Moreover, existing staff may have to take on new roles, whether outside their usual scope of practice, or inappropriate to their level of experience. The unintentional and unsupported substitution of tasks, as an emergency response to lack of staff, is likely to reduce quality of care. Examples exist of midwives and nurses providing basic emergency obstetric care in remote rural areas where doctors are absent,Citation34 and there are anecdotal reports of untrained staff having to deliver babies.Citation35 Ward attendants, relatives and escorts may have to do more basic patient care (bathing, feeding, escorting) due to staff shortages.Citation29Citation35

However, the intentional and supported substitution of tasks, or enhancement of the roles and skills of a lower-level cadre, may increase the efficiency and quality of services, if carefully planned and managed. Several countries (for example, Burkina Faso, Malawi, Mozambique, Tanzania and Zambia) use mid-level health staff to manage clinical services, including obstetric complications and caesarean deliveries. The annual production of these workers can match or exceed the production of doctors.Citation36 Although few studies are available, comparisons of surgical procedures and caesarean deliveries performed by doctors and their substitutes in Mozambique suggest that with adequate supervision and support, clinical decision-making and outcomes by substitutes can be as good as with professional staff.Citation37Citation38

The extent of departures by health professionals makes it difficult for managers to maintain adequate staffing and quality of care.Citation20 For example, 57 registered nurses left the main teaching hospital in the Gambia from 1998 to 2003, contributing to a vacancy rate of 33% in 2003. In the same period, about 223 registered nurses graduated nationally. Thus, the equivalent of one-fourth of the graduates left the country from one teaching hospital.Citation29 Of those leaving, 36 (63%) did not give the required period of notice, and some gave no notice. When working under bureaucratic civil service rules, human resources managers lack the ability to recruit even temporary staff quickly. In a context of overall shortages, managers may not even bother advertising for vacancies that they know are difficult to fill, for example, in less desirable locations.Citation32 The financial and other costs associated with high staff turnover and recruitment put considerable strain on budgets and management capacity.

Many countries have decentralised responsibilities for staff recruitment to lower levels of the health system, but the necessary management capacity needs time and resources to be developed. An example of the effects of inadequate human resources management and attention to health worker motivation comes from South Africa, where physical and verbal abuse of women in midwife obstetric units was documented.Citation39

Lastly, the nature of migration flows means a few staff leaving may accelerate staff attrition. The remaining staff observe that finding new employment is possible, and may learn from the experiences or follow the routes of departing staff.

Effects of shortages on maternal health care

“At the workplace there are always staff shortages. This hospital is very busy. We have about 80 deliveries in 24 hours. So you can imagine how I manage with my skeleton staff. It has not been very easy. You cannot satisfy your clients. Because if there are long queues, you are trying to fight to finish the long queue and you don't have time to talk to your client to counsel her … So you don't satisfy the client and you don't satisfy yourself. You are also frustrated. The queue is too long. You become so irritable. You don't even want to hear anybody talking. Then you frustrate the employer since you are not giving quality services.” (Nurse, urban hospital, Kenya, p.18)Citation40

What is the relationship between staffing shortages and quality of patient care? Most evidence comes from high-income country health systems, and generally supports the intuitive association between shortages and reduced quality of care. A review of “safe staffing” levels for nursing care suggested an inverse relationship between registered nurse staffing levels and patient mortality, and that work stress (including overtime) has adverse effects in terms of staff injury and illness, but less clear effects on patient outcomes.Citation41 A Cochrane Review of delivery care showed that the continuous presence of a support person reduced the need for pain relief and operative deliveries and led to better condition of the newborn.Citation42 A UK study reported that midwifery shortages and poor deployment led to adverse events such as personal injury and frequent near-misses, such as delays in carrying out emergency caesarean sections , which had fortunately not resulted in injury to the mother or infant.Citation43

However, little published research from sub-Saharan Africa exists on the effects of staff shortages on the quality of care, particularly for maternal health. Currently, safe motherhood initiatives are centred on two inter-related strategies: skilled attendants at delivery and emergency obstetric care. Both need an enabling environment, which includes adequate equipment, supplies, referral systems and effective human resources training, supervision and deployment.Citation3

A needs assessment of five countries in Africa highlighted how shortages of health professionals reduced the number of facilities equipped to offer emergency obstetric care (basic and comprehensive), and the number that could be open 24 hours a day.Citation44 As expected, coverage was worse in rural and isolated areas. Some facilities would contact health professionals to respond to emergencies out of hours, but the effectiveness of this depends on the communication infrastructure and the distance between the facility and the professional's residence. In Tanzania, availability of qualified staff was found to be an important determinant of utilisation of emergency obstetric care, alongside other factors of staff motivation, availability of equipment and drugs, and management capacity.Citation18

Other related mechanisms through which staff shortages may result in reduced quality of care include:

| • | Increased workload Reported nurse–patient ratios in Malawi of 1:120 in general wards, 1:50 for maternity and paediatrics,Citation35 1:26 for neonatal and 1:51 for gynaecological patients,Citation45 were perceived by professionals as too low for safe patient care. A study in Zimbabwe from 1995–2000 of fluctuations in workload for doctors, pharmacists, midwives and nurses found an approximate doubling in workload over three years for midwives in a polyclinic (primary health centre).Citation20 | ||||

| • | Increased waiting times At a minimum these reduce patient satisfaction (leading to decreased utilisation), but in an obstetric emergency can cause delays resulting in death, illness or disability for mother and infant. | ||||

| • | Reduced time for the patient The inability of nurses to monitor closely the condition of acutely ill patients, and to react quickly, has been associated with higher patient mortality.Citation46 | ||||

| • | Poorer infection control Evidence on the prevalence and causes of post-partum infections in women in sub-Saharan Africa is lacking. However, newborns are highly vulnerable to infection and their deaths from infection are commonly reported. In a 2005 infection outbreak at a South African hospital, resulting in 21 neonatal deaths, contributory factors cited were high bed occupancy rates, poor infection prevention, staff shortages and heavy staff workloads.Citation47 | ||||

The fatal results of such mechanisms are demonstrated in Malawi. One hospital in ten is closed due to lack of staff; in some, shortages of midwives result in hospital cleaning staff carrying out deliveries. In rural areas, one midwife may have to run the whole health centre 24 hours a day, 7 days a week.Citation3 The declining quality of care and use of health facilities for delivery, and the increase in maternal deaths from HIV/AIDS, have resulted in a dramatic deterioration in maternal health over the past decade.Citation3

Other indirect effects can also reduce the quality of maternal health care. The loss of “institutional memory” from large staff turnover results in a duplication of work and wastage of resources. This is especially relevant for rapidly evolving programmes in reproductive health, HIV/AIDS and tuberculosis, where strategies must be reinvented and re-taught, due to the loss of key personnel and the resulting loss of continuity. Emigration of academics and experienced supervisory personnel can also lead to deficiencies in the professional attachment and supervision of new graduates, or within training institutes. For example, at Ndola Central Hospital, Zambia, 2003, only 32% of sanctioned staff in the School of Nursing and Midwifery were in place.Citation48

The loss of professional leadership more generally is a particular worry. The International Council of Nurses considers leadership development as a critical underpinning for improving both clinical and managerial aspects of utilising the skills of nurses, and provides support to national nurses' associations in many countries to develop capacity to deal with human resources issues.Citation6 Nursing, midwifery and obstetrics councils and organisations have key advocacy and policy development roles which can be undermined by the loss of even a few professional leaders. Experienced academics and managers can train and mentor the next generation of professionals, conduct research to guide health and staff policies, and contribute to the overall development of the health sector. However, such leaders are never numerous in and may be the most “exportable” of health professionals.

Policy implications

“Adequate human resource availability is … central for any large-scale attempt to increase the reach of health systems. Further, human resource availability is likely to determine the capacity to absorb additional financial resources and thus the pace of scaling up.”(p.5)Citation10

Globally, over the next decade, an extra 334,000 professionals with midwifery skills need to be produced and 140,000 upgraded.Citation3 Additionally, 27,000 doctors and technicians need to learn skills to back-up maternal and newborn care. WHO estimates that US$91 billion is needed to scale up maternal and newborn services; it further estimates that a doubling or even trebling of salaries would be the minimum necessary to recruit and retain staff.Citation3 These are breathtaking numbers. The possibility of finding such resources is uncertain. Increasing public sector health workers' salaries, to the exclusion of other sectors and professions, would be politically and economically difficult.Citation49 Even if developing countries did increase their workforces, health care expenditures would still have to fit within economic growth projections and requirements for fiscal sustainability.Citation50

Shortages and maldistribution of health professionals in sub-Saharan Africa are not new phenomena, and in some locations, health workers, managers and communities may perceive them as “normal”.Citation51 The past five years, however, have seen some health systems losing many more maternal health professionals, particularly due to emigration and HIV-related ill-health. Poor and rural women are disproportionately affected, as they are left to receive services from overstretched, under-qualified staff, from traditional, unqualified health practitioners, or from private, often expensive facilities.

Globally, maternal mortality has declined significantly since the 1980s. This is strongly associated with the use of skilled attendants at delivery, which has increased from around 42% to 52% in the developing world.Citation1 Caesarean delivery (an indicator of access to life-saving care for obstetric complications in areas of very low access to health care) increased from 2% to 14% in Asia and North Africa. However, in sub-Saharan Africa, little change occurred in the use of skilled attendants (from 40% to 43%), caesarean delivery increased only from 3% to 4% over the decade, and maternal mortality remained at the highest level in the world, 920 deaths per 100,000 live births.Citation1

What is needed to improve maternal health outcomes? A simplistic response is: to make sure that all women use skilled care during pregnancy, delivery and the post-natal period. But how can the health system provide services to ensure high levels of utilisation? Clearly, adequate numbers and distribution of health professionals are necessary, but not sufficient. Staff must provide quality care: both responsive care that makes services more attractive to mothers and communities, and care that meets professional standards. Although this paper has focused on the availability of staff and facilities for pregnancy, delivery and post-partum care, other services are also critical in reducing maternal mortality. For example, midwives and nurses who provide family planning, safe abortion and post-abortion care, especially at primary care levels, are key to reducing the estimated 13% of maternal deaths worldwide from complications of unsafe abortion.Citation3

More evidence is emerging on the inter-relatedness of job satisfaction, staff retention, staffing levels, skill mix, good human resources management practices, good quality health care and positive health outcomes. Organisational cultures which incorporate flexible employment practices to enable staff to combine work and non-work commitments are particularly helpful to maternal health care providers, many of whom are women. Participatory decision-making, team-working, opportunities for professional development, and adequate pay and recognition are welcomed by all staff, but are especially important for midwives and nurses in physician-dominated health systems. All these factors are associated with lower turnover, increased job satisfaction and better health outcomes. To reduce the “push” factors in migration, these practices must be designed for local contexts and labour markets; a “one-size-fits-all” approach will not work, even within one country.

At local district and facility levels, strategies to reduce attrition and re-attract departed health professionals are the most feasible and quickly implemented actions. In Ghana and the Gambia, for example, managers can provide financial incentives (soft loans for housing, bonuses for overtime work), allow part-time work and flexible work schedules for nurses and midwives, contract retired staff, and pay student nurses and midwives to work during their holidays.Citation29Citation33 The ability of managers to respond quickly and appropriately is determined by the policy environment; for example, autonomous hospitals and decentralised health systems have more flexibility to respond to human resources issues. It is critical that they also have the management capacity to do so. Since attrition of health professionals is likely to continue (if not increase) in the short-term in some countries, both human resources and maternal service managers must cooperate to determine how to improve staff management and obtain good performance in this complex environment.

At the national level, responses by governments to health professional shortages generally involve such actions as negotiating reduced recruitment by higher-income countries; improved workforce planning; revised legislation to enable mid-level providers to perform procedures currently restricted to medical practitioners; increasing inflow through training, and bonding graduates to work in the public sector (and sometimes rural locations) for a fixed term. Increasing training inflow is of fundamental importance, but is costly, takes time, and is dependent on increasing the number of teachers. Some health systems are being more flexible in recruiting trainees, e.g. accepting older adults, selecting trainees from difficult areas and training them locally in the hope they will be more likely to work there, or recognising auxiliary qualifications as part of professional training.

Overall, the health and equity implications of shortages and maldistribution of maternal health professionals in sub-Saharan Africa have not been well documented. Little reliable information exists on the numbers of health professionals who are leaving, and even less on the implications for access to, and quality of, maternal health care. The economic costs of staff attrition are largely unknown, and the cost-effectiveness of different models of nursing and midwifery training and deployment of different skill mixes has not been assessed. One prominent gap in the evidence-base is evaluations of human resources interventions to address shortages and maldistribution, and interventions to maintain accessibility and quality of maternal health care in this context. Without such evidence, civil society, professional organisations, national governments and development partners face difficulties in advocating effectively for the required responses.

If governments and development partners are serious about reaching the Millennium Development Goal on maternal health and protecting the reproductive rights of women, more attention is needed to address shortages of maternal health professionals, and of overall human resources policy in sub-Saharan Africa. The World Health Organization is positioned to take international leadership, and the focus of the 2006 World Health Report on the health workforce reflects their increasing concern. Development assistance programmes of wealthy countries are only beginning to develop responses, for example, by funding recurrent salary expenditures, the expansion of training programmes, supporting health professionals to work in developing countries, or by allowing migrants to temporarily share their skills in their home countries without jeopardising their immigration status.

More fundamentally, a rethink of health sector reforms and overall macro-economic development policies is needed, to focus on equity, participation by the poor and strengthening the role of the state. The problems of low-income countries are often related to problems in wealthier countries, and in this case, the failure of wealthier countries to produce sufficient health professionals for their own populations is seriously affecting low-income countries. Finally and most challengingly, it must be recognised that the fundamental issue underlying the migration of health professionals from poor to better-off regions and countries, of inequitable access to health care, and of inequitable health outcomes, is the vast and unjustifiable difference in wealth between the few rich and the many poor countries.

Notes

1 Figures for nurses and midwives separately are not available, and are therefore combined. Health professionals are usually required to register with a professional body in the receiving country when seeking employment, giving one source of data on emigration. However, not all receiving countries collate or publish registration data by country of application (or nationality of applicant), and not everyone who registers in a receiving country actually migrates and takes up employment there.

References

- C AbouZahr. Assessing Trends in Maternal Mortality. 2003; Global Forum for Health Research: Geneva. At: <http://Www.Globalforumhealth.Org/Forum7/CDRomForum7/Tuesday/InvestingAbouFull.Doc. > Accessed 6 January 2006.

- World Health Organization UNICEF UNFPA. Maternal mortality in 2000: Estimates developed by WHO, UNICEF, UNFPA. 2004; WHO: Geneva.

- World Health Organization. The World Health Report 2005: Make Every Mother and Child Count. 2005; WHO: Geneva.

- K Wyss. An approach to classifying human resources constraints to attaining health-related Millennium Development Goals. Human Resources for Health. 2(1): 2004

- Joint Learning Initiative. Human Resources for Health: Overcoming the Crisis. 2004; The President and Fellows of Harvard College: Cambridge MA.

- J Buchan, L Calman. The Global Shortage of Registered Nurses: An Overview of Issues and Actions. 2004; International Council of Nurses: Geneva.

- OK Munjanja, S Kibuka, D Dovlo. The Nursing Workforce in Sub-Saharan Africa. 2005; International Council of Nurses: Geneva.

- K Diallo. Data on the migration of health-care workers: sources, uses, and challenges. Bulletin of World Health Organization. 82(8): 2004; 601–607.

- C Kurowski. Scope, Characteristics and Policy Implications of the Health Worker Shortage in Low-Income Countries of Sub-Saharan Africa. 2004; World Bank: Washington DC.

- C Kurowski, K Wyss, S Abdulla. Human Resources for Health: Requirements and Availability in the Context of Scaling Up Priority Interventions in Low-Income Countries. Case Studies From Tanzania and Chad, HEFP Working Paper 01/04. 2004; London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine: London.

- Dovlo D. The Brain Drain and Retention of Health Professionals in Africa. A Case Study. Paper Presented at: Regional Training Conference on Improving Tertiary Education in Sub-Saharan Africa: the Things That Work! Accra, 23–25 September. 2003.

- D Dovlo. Report on Issues Affecting the Mobility and Retention of Health Workers/Professional in Commonwealth African States. 1999; Commonwealth Secretariat: London.

- LS Mackintosh. A study identifying factors affecting retention of midwives in Malawi Dissertation. 2003; Liverpool School of Tropical Medicine: Liverpool.

- Brain drain haunts health sector. The Herald (Zimbabwe). 29 April 2005.

- Nursing and Midwifery Council. Statistical Analysis of the Register, 1 April 2003 to 31 March 2004. 2004; Nursing and Midwifery Council: London.

- Africa Working Group of the JLI on Human Resources. The Health Workforce in Africa: Challenges and Prospects. 2004; Global Health Trust: Cambridge MA.

- Malawi Institute of Management. The Migration of Health Workers in the African Region: the Malawi Scenario. 2003; University of Malawi: Lilongwe.

- EO Olsen, SS Ndeki, OF Norheim. Human resources for emergency obstetric care in northern Tanzania: distribution of quantity or quality?. Human Resources for Health. 3(5): 2005

- UN Millennium Project. Who's Got the Power? Transforming Health Systems for Women and Children. 2005; Earthscan: London.

- M Awases, A Gbary, J Nyoni. Migration of Health Professionals in Six Countries: a Synthesis Report. 2004; WHO Regional Office for Africa: Brazzaville.

- M Vujicic, P Zurn, K Diallo. The role of wages in the migration of health care professionals from developing countries. Human Resources for Health. 2(1): 2004; 3.

- A Chikanda. Medical Leave: The Exodus of Health Professionals from Zimbabwe. 2005; Southern African Migration Project: Cape Town.

- W Van Lerberghe, O Adams, P Ferrinho. Human resources impact assessment. Bulletin of World Health Organization. 80(7): 2002; 525.

- EJ Hall. The challenges HIV/AIDS poses to nurses in their work environment. Centre for Health Policy. HIV/AIDS in the Workplace: Symposium Proceedings Johannesburg: University of the Witwatersrand. 2004; 109–122.

- V Narasimhan, H Brown, A Pablos-Mendez. Responding to the global human resources crisis. Lancet. 363(9419): 2004; 1469–1472.

- J McIntyre. Maternal health and HIV. Reproductive Health Matters. 13(25): 2005; 129–135.

- S Anand, T Barnighausen. Human resources and health outcomes: cross-country econometric study. Lancet. 364(9445): 2004; 1603–1609.

- W Graham, JS Bell, CHW Bullough. Can skilled attendance at delivery reduce maternal mortality in developing countries?. W Van Lerberghe, V De Brouwere. Safe Motherhood Strategies: A Review of the Evidence. 2001; ITGPress: Antwerp.

- MM Jagne. Human resource issues affecting nurses in Royal Victoria Teaching Hospital, Gambia: what can be done?. Dissertation. 2004; University of Leeds.

- A Baumann, LL O'Brien-Pallas. Commitment and Care: The Benefits of a Healthy Workplace for Nurses, Their Patients and the System. 2001; Canadian Health Service Research Foundation: Ottawa.

- EJ Hall. Nursing attrition and the work environment in South African health facilities. Curationis. 27(4): 2004; 28–36.

- J Xaba, G Phillips. Understanding Nurse Emigration: Final Report. 2001; Trade Union Research Project: Pretoria.

- MM Al-Hassan. The causes and effects of international migration of health professionals: the case of nurses at the Korle-Bu Teaching Hospital in Ghana Dissertation. 2004; University of Leeds.

- L Pearson, R Shoo. Availability and use of emergency obstetric services: Kenya, Rwanda, Southern Sudan, and Uganda. International Journal of Gynecology and Obstetrics. 88(2): 2005; 208–215.

- JM Aitken, J Kemp. HIV/AIDS, Equity and Health Sector Personnel in Southern Africa. Equinet Discussion Paper No.12. 2003; Equinet: Harare.

- D Dovlo. Using mid-level cadres as substitutes for internationally mobile health professionals in Africa. A desk review. Human Resources for Health. 2(1): 2004

- F Vaz, S Bergstrom, ML Vaz. Training medical assistants for surgery. Bulletin of World Health Organization. 77(8): 1999; 688–691.

- C Pereira, A Bugalho, S Bergstrom. A comparative study of caesarean deliveries by assistant medical officers and obstetricians in Mozambique. British Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology. 103(6): 1996; 508–512.

- R Jewkes, N Abrahams, Z Mvo. Why do nurses abuse patients? Reflections from South African obstetric services. Social Science and Medicine. 47(11): 1998; 1781–1795.

- K Van Eyck. Women and International Migration in the Health Sector. 2004; Public Services International: Ferney-Voltaire, 18.

- C Kovner. The impact of staffing and the organization of work on patient outcomes and health care workers in health care organizations. Joint Commission Journal on Quality and Patient Safety. 27(9): 2001; 458–468.

- ED Hodnett, S Gates, GJ Hofmeyr. Continuous support for women during childbirth. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 3: 2003; CD003766.

- B Ashcroft, M Elstein, N Boreham. Prospective semi-structured observational study to identify risk attributable to staff deployment, training, and updating opportunities for midwives. BMJ. 327(7415): 2003; 584–586.

- UNFPA. Making Safe Motherhood a Reality in West Africa. Using Indicators to Programme for Results. 2003; UNFPA: New York.

- Dugger CW. An exodus of African nurses puts infants and the ill in peril. New York Times 12 July 2004 p. A6–A7.

- LH Aiken, HL Smith, ET Lake. Lower Medicare mortality among a set of hospitals known for good nursing care. Medical Care. 32(8): 1994; 771–787.

- AW Sturm. Analysis of Klebsiella Outbreak in Neonatal Nursery at Mahatma Ghandi Hospital. 2005; Kwazulu-Natal Department of Health: Pietermaritzburg.

- S Ammassari. Migration and Development: New Strategic Outlooks and Practical Ways Forward. The Cases of Angola and Zambia. 2005; International Organization for Migration: Geneva.

- A Green, N Gerein. Exclusion, inequity and health system development: the critical emphases for maternal, neonatal and child health. Bulletin of World Health Organization. 83(6): 2005; 402.

- High Level Forum on Health MDGs. Addressing Africa's Health Workforce Crisis: an Avenue for Action. 2004; WHO: Abuja.

- Department of Health. Saving Mothers: Report on the Confidential Enquiries into Maternal Deaths in South Africa 1998. 1999; Department of Health: Pretoria.