Abstract

This article highlights the efforts of the Community Health and Development (CHAD) Programme of Christian Medical College to address the issues of gender discrimination and improve the status of women in the Kaniyambadi Block, Vellore, Tamil Nadu, India. The many schemes that are specifically for women and general projects for the community from which women can also benefit represent a multi-pronged approach whose aim is the improvement of women's health, education and employment in the context of community development. However, despite five decades of work with a clear bias in favour of women, the improvement in health and the empowerment of women has lagged behind that achieved by men. We believe this is because the community, with its strong male bias, utilises the health facilities and education and employment programmes more for the benefit of men and boys than women and girls. The article argues for a change of approach, in which gender and women's issues are openly discussed and debated with the community. It would appear that nothing short of social change will bring about an improvement in the health of women and a semblance of gender equality in the region.

Résumé

Cet article décrit les activités du Programme de développement et de santé communautaires (CHAD) du Collège médical chrétien pour traiter les questions de discrimination sexuelle et améliorer la condition des femmes dans la zone de Kaniyambadi Block, Vellore, Tamil Nadu, Inde. Les nombreux projets destinés aux femmes et les projets généraux pour la communauté dont les femmes peuvent aussi bénéficier représentent une approche plurielle dont l'objectif est d'améliorer la santé, l'éducation et l'emploi des femmes dans le contexte du développement communautaire. Néanmoins, malgré cinq décennies de travail axé prioritairement sur les femmes, les améliorations de la santé et de l'autonomisation des femmes sont très en retard par rapport aux hommes. C'est à notre avis parce que la communauté, avec ses forts préjugés en faveur des hommes, utilise les équipements de santé et les programmes d'éducation et d'emploi davantage au bénéfice des hommes et des garçons que des femmes et des filles. L'article préconise un changement d'approche et conseille d'aborder et de débattre ouvertement des questions d'égalité des femmes avec la communauté. Il semble que seul un changement social apportera une amélioration de la santé des femmes et un semblant d'égalité entre les sexes dans la région.

Resumen

En este artículo se destacan los esfuerzos del Programa de Salud y Desarrollo Comunitario (CHAD) del Christian Medical College por tratar los asuntos de discriminación basada en género y mejorar la condición de la mujer en Kaniyambadi Block, Vellore, Tamil Nadu, en la India. Los numerosos planes diseñados para las mujeres y los proyectos comunitarios, que también pueden beneficiar a las mujeres, representan un enfoque de múltiples niveles, cuyo objetivo es mejorar la salud, formación y empleo de las mujeres en el contexto del desarrollo comunitario. No obstante, pese a cinco décadas de trabajo centrado en las mujeres, las mejorías en la salud y su empoderamiento no se comparan con los logros de los hombres. Creemos que esto se debe a que la comunidad, muy parcial a los hombres, utiliza los establecimientos de salud y los programas de formación y empleo más para beneficio de hombres y niños que de mujeres y niñas. En el presente artículo se argumenta a favor de un cambio de estrategia, en la cual los aspectos de género y de las mujeres son discutidos y debatidos abiertamente con la comunidad. Al parecer, sólo un cambio social traerá mejorías para la salud de las mujeres y cierta apariencia de igualdad de los sexos en la región.

The health, education and employment status of women in India have shown significant improvement in many parts of India. However, numerous problems persist. These include the declining sex ratio at birth,Citation1 persisting gender inequalities related to health,Citation2Citation3Citation4 low levels of enrollment and attendance at school of girls, high school drop-out rates and lower educational status among women,Citation5 unequal wages for women for similar work as men's,Citation6 greater unemployment among women and labour laws that favour men,Citation7 problems with micro-credit schemes and their failure to empower women economically,Citation8 an association between female gender, low education, poverty and anxiety and depression,Citation9 and the physical and psychological abuse of women.Citation7Citation8Citation9Citation10Citation11Citation12Citation13Citation14Citation15

The social structure of Indian society and the secondary position women occupy significantly influence every aspect of health.Citation16 Very often the goals of many programmes for women are a rehash of internationally set goals, some of which are not achievable. The second-class status of women in Indian society continues despite efforts by the government and non-governmental organisations. Women's perspectives continue to be missing, marginalised or ignored.

Many community health programmes in the developing world seek to address the issues of gender bias and the unequal status of women,Citation17 with an emphasis on women's health, education and employment. In spite of such efforts, women face discrimination and continued adversity, especially in rural India. This paper reviews the situation of women and the changes over the past decade in Kaniyambadi Block in rural Tamil Nadu and work that has been done to improve the status of women by the Community Health and Development (CHAD) Programme, run by the Department of Community Health, Christian Medical College, Vellore.

The work of the Community Health and Development Program, Vellore

The Department of Community Health, Christian Medical College, Vellore, India, has been working in Kaniyambadi Block for the past 50 years.Citation18Citation19 This region is a geographically defined area of 127.4 sq km with a population of 108, 873 (in 1999). The community health programme operates in all 85 villages in the area. The majority of the population follow the Hindu religion. The language is Tamil. A significant proportion of the population are from the lower socio-economic strata. Agriculture and animal husbandry are the major occupations.

The Community Health and Development (CHAD) Programme is run by the Department. The programme has four major components: health care, animal husbandry and agriculture, adult and non-formal education, and community development. The front line workers of CHAD's health care programme are the community health workers, who are traditional midwives who live in the village and who have been trained by the programme. The community health worker is supported by the community health team (including a doctor, nurse, community extension worker and health aide), who visit every village every two weeks. Cases requiring greater medical input are referred to the base hospital.

The surveillance system has been described in detail elsewhere.Citation20 It consists of a four-tier monitoring system. The Block has been divided into regions with specific personnel in charge of the health care of each region. The system involves the community health worker, the health aide, the community nurse and the doctor. Every week the community health worker reports to the health aide about pregnancies, deliveries, births, deaths, morbidity, marriages, immunisation and couples eligible for contraception in the village. This information is verified by the nurse and subsequently by the doctor. Data on migration into and out of the Block are also collected. Data obtained through this surveillance system are computerised, and the programme managers feed the information back to the health team every month.

Programmes intended to benefit women

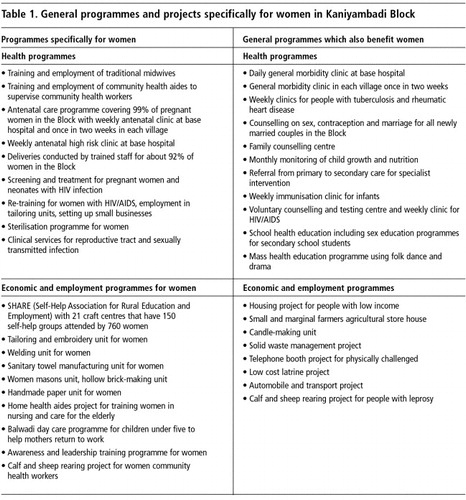

The CHAD programme has sought to make a significant contribution to the advancement of women's health in the region, with an emphasis on care during pregnancy and delivery, contraception, education of girls, women's employment and empowerment. Table 1 lists the CHAD projects that are specifically for women and the general schemes from which women also benefit. Together, these projects represent a multi-pronged approach to the empowerment of women and the improvement of health, educational and employment status in the context of community development. In recognition of the work done by the programme, the World Health Organization conferred the WHO 50th Anniversary Primary Health Care Award on the Department in 1999.

Health indicators for women and girls

In the 1970s and 1980s many community health programmes like ours changed their emphasis from pure health interventions to include development. The argument was that development results in greater health improvements than direct medical interventions alone. This argument was also applied to women's issues, and education and employment for women became core features of community health and development activities. However, despite two decades of focused effort on women's health, education and employment, the health indices for women leave much to be desired.

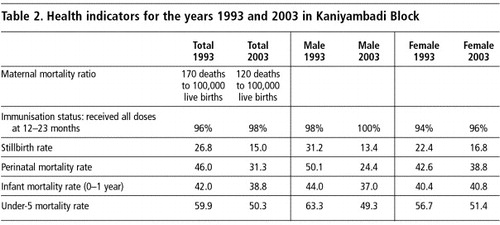

Despite all of CHAD's work and the clear bias in favour of women in CHAD's programmes, the reality on the ground has not changed substantially. Table 2 lists some health indicators for Kaniyambadi Block for the years 1993 and 2003. The figures show some reduction in maternal deaths and an improvement in most indices related to infant health. However, the data on infants show far greater improvement over the decade for male than for female infants. The difference in the change over the decade in the stillbirth rate (×2= 6.0; df=1; p<0.02), the perinatal mortality rate (×2= 15.9; df=1; p<0.001), the infant mortality rate (×2= 7.0; df=1; p<0.01) and the under-5 mortality rate (×2= 4.2; df=1; p<0.04) between boys and girls was statistically significant, with much smaller improvement in these rates for girls.

Girl children continue to be perceived as a liability. Health workers, nurses and physicians working in the programme are very aware of the fact that girl children are often brought to hospital later in the course of illness than boys. Evidence from the region also suggests high rates of reproductive tract infection among young married women, and low rates of treatment-seeking, and postulates that the failure to seek treatment is related to the women's low social status.Citation21

The birth of a girl and failure to conceive a boy child are significant risk factors for post-partum depression in the region.Citation22 Case reports of attempted suicide following the birth of girls are not uncommon. There is a very high suicide rate of 148 per 100,000 young women aged 10–19 yearsCitation23 compared with 55 per 100,000 for young men from the same age group and an average of 95 per 100,000 for the general population in the region.Citation24Citation25

Case reports of physical and sexual assaults on girls and women from the region have been documented in base hospital records of the programme and in local studies.Citation26 A study done among all the women in two randomly selected sectors of the village in the Block revealed that 42.4% (81/191) women suffered some form of physical, mental, socio-economic or sexual violence from their male partners, whereas violence against women where women were the perpetrators was a mere 5.4%. The survey also revealed that physical assault (93.8%) and abusive language (92.5%) were the commonest forms of violence, although a significant number of women (41.9%) admitted being sexually abused. The violence was significantly associated with low education and marriage before the age of 18 in women, women who did not work outside the home and those in joint families, and those with alcohol abuse in their spouses. In-depth interviews with these women revealed that they often blamed themselves for the violence. The data from the base hospital also suggests that while the community utilises the hospital for treatment of women following physical abuse, it refuses to examine or tackle the issue of violence against women itself.

Indicators of social status of women

Women's work is also socially devalued. Women bear the burden of doing household chores, collecting firewood, carrying water from village wells and looking after children. However, such work is taken for granted. Unequal pay for similar work between men and women is also an example of gender discrimination. Qualitative studies by CHAD on sexual behaviour and practice in the area have found that employers often demand sex from women who are widows or separated from their husbands.Citation27 While quantitative data are not available to record changes over time, there is no reason to suspect a reduction in the level of sexual abuse in the region. Issues related to dowry and the inheritance rights of women are glossed over and discrimination against women in the area of property and wealth persists.

Women who are not able to conceive within the first two years of marriage visit the base hospital for treatment. They report that infertility and childlessness are commonly blamed on them and that their husbands are often hesitant to undergo medical tests necessary to establish the cause of infertility in the couple.

Autonomy in decision-making rarely exists for women, such that even decisions related to reproductive and contraceptive choices are not under their own control. Decisions whether or not to use contraception are often forced on women, especially in situations where there is no male child. A survey of spacing of children in the area revealed that the majority of women had a two-year interval between children. However, less than 2% of married couples use temporary methods of contraception. Rather, many women (28%) had induced abortions to achieve spacing.Citation28 These abortions were often done by untrained personnel with a high risk of infection and in some instances death.

Attempts by the government to create space for a political voice for women, by reserving a third of panchayat (village council) posts for women in the region, have also been thwarted. The male relatives of the women thus elected control the day-to-day functioning of the local bodies in the Block through them.

These examples clearly suggest that the local community has used the facilities and programmes offered by CHAD to push its male-dominated agenda. It has utilised the health care, education and employment provided more for its men and boys than for its women and girls.

Use of health technology against women country-wide

A recent study analysed data obtained for the Special Fertility and Mortality Survey undertaken in 1998.Citation29 Ever-married women living in 1.1 million households in 6,671 nationally-representative units were asked questions about their fertility history and children born in 1997. For the 133,738 births studied for 1997, the adjusted sex ratio for the second birth when the preceding child was a girl was 759 per 1000 males (99% CI 731–787). The adjusted sex ratio for the third child was 719 (675–762) if the previous two children were girls. By contrast, adjusted sex ratios for second or third births if one or both of the previous children were boys were 1102 and 1176, respectively. Mothers with grade 10 or higher education had a significantly lower adjusted sex ratio (683, 610–756) than did non-literate mothers (869, 820–917). The study concluded that prenatal sex determination followed by abortion of female fetuses is the most plausible explanation for the low sex ratio at birth in India. Women most likely to practise sex selective abortion were those who already had one or two girl children. Other studies have reported an inverse relationship between the number of ultrasound machines in an area and the decline in male–female sex ratios.Citation1 Education of women in this instance appears not to have worked for women, but rather contributed to the use of medical technology to do actual harm to the status of women in Indian society.

Recent programmes and future plans

Based on the analysis of the situation over the past many years, the CHAD programme has been slowly but surely making changes in its approach to gender equity. The evidence argues for the need to change approaches. We are no longer convinced that we can succeed in improving women's health or status unless CHAD's programmes attempt to confront gender bias openly. For too long, our community programmes have been refusing to discuss women's issues openly with the community. We now believe that it is time to do so. It would appear that nothing short of social change will bring about an improvement in the health of women in the region. While such a social revolution may be a big task for community health programmes, the failure to acknowledge this situation until now needs discussion and debate.

CHAD has recently introduced a number of programmes which attempt to challenge gender stereotypes in the community. Issues related to gender equity are now taught as part of sexuality education in high schools. Gender issues are also discussed among groups for children who drop out of school. These issues are also debated in women's self-help and women's groups. Gender issues are discussed with all newly married couples in the Block with the aim of promoting equal responsibility and gender equality. Many women who attend the family counselling centre have gender-related problems. Difficult problems involving legal issues are managed by the combined efforts of the family counselling centre and the women's police stations.

Programmes for boys and young men that aim to change attitudes towards girls and women and traditional gender roles are also a crucial part of achieving social change. Family life education, gender awareness, men's shared responsibility in parenthood and sexual behaviour and shared contribution to family income, health and nutrition, prevention of violence against women and counselling and services for sexual and reproductive health will prove useful at community level and in schools and colleges. Such strategies should be part of a dialogue with the community, with men and with older women who seem to maintain the present status quo

Untouchable women who have taken control of the granite quarry in which they used to labour for less than $1 a day, Tamil Nadu, India

The CHAD programme will continue to analyse data disaggregated by gender.Citation30 Our staff will also have to be re-sensitised to the gender issue. All future programmes will have to be viewed through a gender lens in order that they are able to result in equality of health and social outcomes for males and females, and not just seek to provide increased opportunity for women.

Government initiatives

The Government of Tamil Nadu has also recently introduced many initiatives to combat gender inequality, including increased financial assistance and credit for tribal and lower-caste women to buy land and a micro-credit scheme for women's self-help groups.Citation31 The government also provides bicycles for girls from low-caste and tribal backgrounds who want to pursue schooling in the 11th and 12th grade. It has established an all-women's police force, and police stations and courts to handle issues faced by women.Citation31 While it is too early to evaluate the long-term impact of these schemes, their influence is already evident in the education sector with an increase in enrollment of girls in high schools.

There is also a need to review laws related to family, marriage, property and succession rights,Citation32Citation33 and policies to enforce equal wages and conditions for similar work. There is also a need to increase the representation and involvement of women in policy-making and politics. Involving local industries and local government in these efforts is crucial.

Many in India seem to consider violence against women within the household as an accepted social norm. Stopping domestic violence requires a coordinated community response in which health care providers, the criminal justice system and social services join forces.

While many of these reforms are necessary they may not be sufficient to bring about the massive social change required. There is a definite need to engage communities and the population as a whole in a debate to challenge traditional stereotypes and accepted social norms.

Conclusion

Efforts at achieving gender equality with increased opportunities to improve women's health, education and employment have resulted in continued poorer outcomes for women in terms of health and social indices. While much has improved, the improvement is not significant when compared with that achieved for boys and men. The main reason why this is the case, we believe, is that the community utilises the available programmes more for the benefit of men and boys than for women and girls. There is a need for aggressive gender justice in order for women in India to achieve equal health and social status in the foreseeable future. Programmes to achieve gender equality should not only focus on the provision of equal or greater opportunities for women. They should also concentrate on achieving equality in gender outcomes within a reasonable time frame. To accomplish this, all plans and projects within community programmes need to be examined through a gender lens.

References

- A Bardia, E Paul, SK Kapoor. Declining sex ratio: role of society, technology and government regulation in Faridabad district, Haryana. National Medical Journal of India. 17: 2004; 207–211.

- RP Pande, AS Yazbeck. What's in a country average? Wealth, gender, and regional inequalities in immunization in India. Social Science & Medicine. 57: 2003; 2075–2088.

- A Pandey, PG Sengupta, SK Mondal, DN Gupta, B Manna, S Ghosh, D Sur, SK Bhattacharya. Gender differences in healthcare-seeking during common illnesses in a rural community of West Bengal, India. Journal of Health Population and Nutrition. 20: 2002; 306–311.

- B Cowan. Let her die. Indian Journal of Maternal and Child Health. 1: 1990; 127–128.

- S Ananthakrishnan, P Nalini. Social status of the rural girl child in Tamil Nadu. Indian Journal of Pediatrics. 69: 2002; 579–583.

- G Rajamma. Empowerment through income-generating projects. Focus on Gender. 3: 1993; 53–55.

- United Nations Development Program. Moving from policy to practice: A gender mainstreaming strategy for UNDP India. http://www.undp.org/gender/resources/India.

- L Mayoux. Women's empowerment and micro-finance programmes: strategies for increasing impact. Development in Practice. 8: 1998; 235–241.

- V Patel, R Araya, M de Lima, A Ludermir, C Todd. Women, poverty and common mental disorders in four restructuring societies. Social Science & Medicine. 49: 1999; 1461–1471.

- SJ Jejeebhoy. Associations between wife-beating and fetal and infant death: impressions from a survey in rural India. Studies in Family Planning. 29: 1998; 300–308.

- A Peedicayil, LS Sadowski, L Jeyaseelan, V Shankar, D Jain, S Suresh, SI Bangdiwala, IndiaSAFE Group. Spousal physical violence against women during pregnancy. British Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology. 111: 2004; 682–687.

- L Ramiro, F Hassan, A Peedicayil. Risk markers of severe psychological violence against women: a WorldSAFE multi-country study. Injury Control and Safety Promotion. 11: 2004; 131–137.

- VF Go, CJ Sethulakshmi, ME Bentley, S Sivaram, AK Srikrishnan, S Solomon, DD Celentano. When HIV-prevention messages and gender norms clash: the impact of domestic violence on women's HIV risk in slums of Chennai, India. AIDS and Behavior. 7: 2003; 263–272.

- Abha, Geetanjali, Radha, Ratna. Nyay karo ya jail bharo – Sathins of Rajasthan demand justice. Manushi 1992;72:18–20.

- P Roy. Sanctioned violence: development and the persecution of women as witches in south Bihar. Development in Practice. 8: 1998; 136–147.

- M Desai. Empowering the family for girl child development. Social Change. 25: 1995; 38–43.

- M Sharma, G Bhatia. The voluntary community health movement in India: a strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, and threats (SWOT) analysis. Journal of Community Health. 21: 1996; 453–464.

- J Patterson. There rest thy feet: The CHAD Experience. 1990; Community Health Department, Christian Medical College: Vellore.

- J Patterson. Signs of the times. 2005; Community Health Department, Christian Medical College: Vellore.

- A Joseph, KS Joseph, K Kamaraj. Use of computers in primary health care. International Journal of Health Sciences. 2: 1991; 93–101.

- JH Prasad, S Abraham, KM Kurz. Reproductive tract infections among young married women in Tamil Nadu, India. International Family Planning Perspectives. 31: 2005; 73–82.

- M Chandran, P Tharyan, J Muliyil. Post-partum depression in a cohort of women from a rural area of Tamil Nadu, India. Incidence and risk factors. British Journal of Psychiatry. 181: 2002; 499–504.

- R Aaron, A Joseph, S Abraham. Suicides in young people in rural southern India. Lancet. 363: 2004; 1117–1118.

- A Joseph, S Abraham, JP Muliyil. Suicide rates in rural India using verbal autopsies, 1994–9. BMJ. 326: 2003; 1121–1122.

- J Prasad, VJ Abraham, S Minz. Rates and factors associated with suicide in Kaniyambadi Block, Tamil Nadu, South India, 2000–02. International Journal of Social Psychiatry. 52: 2006; 65–71.

- Ghosh P, Jehangir S, Abraham VJ, et al. Violence against women in Kaniyambadi Block, Tamil Nadu: quantitative and qualitative studies. (Unpublished data)

- John R, Prasad J, Abraham S, et al. Sexual behaviour and symptoms of reproductive tract infection among adolescents: qualitative and quantitative studies in rural South India. Indian Journal of Public Health 2006 (in press).

- P Varkey, PP Balakrishna, JH Prasad. The reality of unsafe abortion in a rural community in South India. Reproductive Health Matters. 8: 2000; 83–91.

- P Jha, R Kumar, P Vasa. Low male-to-female sex ratio of children born in India: national survey of 1.1 million households. Lancet. 367: 2006; 211–218.

- Sandler J. UNIFEM's Experiences in Mainstreaming for Gender Equality. At: <http://www.unifem.org/index.php?f_page_pid=188>.

- Government of Tamil Nadu. Social Welfare and Nutritious Meal Programme Department, Policy Note - 2005–2006, Development of Women. At: <http://www.tn.gov.in/policynotes/social_welfare_4.htm>.

- Parashar A. Family law as a means of ensuring gender justice for Indian women. Indian Journal of Gender Studies 1997;4:199–29.

- V Reddy. A blow to gender equality. Supreme Court judgement on Manushi's case on women's land rights. Manushi. 1999; 24–25.