Abstract

Public information campaigns are an integral component of reproductive health programmes, including on abortion. In India, where sex selective abortion is increasing, public information is being disseminated on the illegality of sex determination. This paper presents findings from a study undertaken in 2003 in one district in Rajasthan to analyse the content of information materials on abortion and sex determination and people's perceptions of them. Most of the informational material about abortion was produced by one abortion service provider, but none by the public or private sector. The public sector had produced materials on the illegality of sex determination, some of which failed to distinguish between sex selection and other reasons for abortion. In the absence of knowledge of the legal status of abortion, the negative messages and strong language of these materials may have contributed to the perception that abortion is illegal in India. Future materials should address abortion and sex determination, including the legal status of abortion, availability of providers and social norms that shape decision-making. Married and unmarried women should be addressed and the participation of family members acknowledged, while supporting independent decisions by women. Sex determination should also be addressed, and the conditions under which a woman can and cannot seek an abortion clarified, using media and materials accessible to low-literate audiences. Based on what we learned in this research, a pictorial booklet and educator's manual were produced, covering both abortion and sex determination, and are being distributed in India.

Résumé

Les campagnes d'information font partie intégrante des programmes de santé génésique, notamment sur l'avortement. En Inde, où les avortements sélectifs selon le sexe du foetus augmentent, des informations sont diffusées sur l'illégalité de la prédétermination du sexe. Cet article présente les conclusions d'une étude de 2003, réalisée dans un district du Rajasthan, qui a analysé le contenu des matériels d'information sur l'avortement et la détermination prénatale du sexe, ainsi que la manière dont la population les perçoit. La plupart des matériels d'information sur l'avortement ont été produits par un prestataire de services d'avortement, mais aucun par le secteur public ou privé. Le secteur public a produit des matériels sur l'illégalité de la prédétermination du sexe, dont certains ne distinguaient pas la sélection prénatale d'autres motifs d'avortement. En l'absence de connaissances sur le statut juridique de l'avortement, les messages négatifs et le langage énergique de ces matériels ont pu faire croire que l'avortement était illégal en Inde. Les futurs matériels doivent aborder l'avortement et la prédétermination du sexe, y compris le statut juridique de l'avortement, la disponibilité de prestataires et les normes sociales qui façonnent les décisions. Ils doivent s'adresser aux femmes mariées et célibataires, et tenir compte de la participation de la famille, tout en soutenant une décision indépendante des femmes. Il faut aussi parler de la détermination prénatale du sexe, et clarifier des conditions auxquelles une femme peut demander un avortement, avec des médias et des matériels accessibles aux publics peu alphabètes. Une brochure illustrée et un manuel des éducateurs, couvrant l'avortement et la détermination du sexe, ont été produits grâce aux conclusions de cette recherche et sont distribués en Inde.

Resumen

Las campañas de información pública son un elemento integral de los programas de salud reproductiva. En la India, donde el aborto por selección de sexo sigue en alza, se está difundiendo información sobre la ilegalidad de la determinación del sexo. En este artículo se exponen los resultados de un estudio de 2003 realizado en un distrito de Rajasthan para analizar el material informativo sobre el aborto y la determinación del sexo, así como las percepciones de la gente al respecto. Gran parte del material sobre el aborto fue producida por un prestador de servicios de aborto, pero ninguno por el sector privado o público. Este último había producido materiales sobre la ilegalidad de la determinación del sexo, algunos de los cuales no distinguen entre la selección del sexo y otros motivos para tener un aborto. A falta de conocimiento del estado legal del aborto, los mensajes negativos y el fuerte lenguaje de estos materiales posiblemente contribuyeron a la percepción de que el aborto es ilegal en la India. En futuros materiales se debe tratar el aborto y la determinación del sexo, incluido el estado legal del aborto, la disponibilidad de los prestadores de servicios y las normas sociales que influyen en la toma de decisiones. Se debe hablar sobre las mujeres casadas y solteras y apoyar sus decisiones independientes, pero también reconocer la participación de sus familiares. Usando los medios de comunicación y materiales accesibles a un público casi analfabeto, se deben aclarar las condiciones bajo las cuales una mujer puede o no buscar un aborto. A raíz de lo que se aprendió en esta investigación, se produjo un folleto ilustrado y un manual del educador, que abarcan el aborto y la determinación del sexo, y se están distribuyendo en la India.

In many countries, public information and media campaigns about the legality of abortion are an important strategy for improving access to safe abortion services. In India, where the dynamics of son preference and gender inequality have led to the practice of sex determination followed by sex selective abortion, public information is also used to communicate messages on the illegality of sex determination and the positive attributes of girl children. Governmental and non-governmental organisations (NGOs) have produced information materials in formats such as flipcharts, pamphlets, posters, and radio and television spots to address these issues. Yet very little is known about the development of such materials or their content, or people's perceptions of and access to them.

Anecdotal evidence suggested that materials about sex determination and sex selective abortion were much more widely disseminated than information about abortion itself. Several qualitative studies undertaken as part of the national Abortion Assessment Project-India found that awareness among women and service providers of legislation pertaining to sex determination was far greater than knowledge of the legal status of abortion in India.Citation1 There was also anecdotal evidence that publicity in recent years on the illegality of sex determination may have created a mistaken belief that abortion was illegal. We believed this merited further study and analysis.

Abortion was legalised in India through the Medical Termination of Pregnancy (MTP) Act in 1971 with the strong support of medical professionals.Citation2 Abortion is permitted up to 20 weeks for a range of social and medical reasons including if the pregnancy endangers the physical or mental health of the mother, may result in the birth of a child with physical or mental abnormalities, is a result of rape (excluding marital rape) or of contraceptive failure in a married woman.Citation3 Generally, the clause on contraceptive failure has been liberally interpreted. Two recent amendments to the MTP Act aimed to reduce bureaucratic delays and hurdles in provider and clinic certification and increase access to safe abortion services.Citation4Citation5

Although women in India have had a legal right to abortion for over 30 years, up to 90% of the estimated six million abortions occurring annually continue to be performed either at uncertified facilities and/or by uncertified providers, and are often unsafe.Citation6Citation7 Illegal providers include a vast array of practitioners from the formal and informal sectors.Citation7Citation8 In Rajasthan, a study by the Indian Council of Medical Research showed that informal providers performed more abortions than government doctors and private doctors combined.Citation9

Community-based studies suggest that the vast majority of men and women – up to 85% – may be unaware that abortion is legal in India.Citation10Citation11 Moreover, the lack of information and knowledge about the legal status and availability of safe abortion services present a significant obstacle to women seeking safe abortion in India. Thus, almost one tenth of all maternal deathsCitation12 and significant morbidity are due to complications of unsafe abortion.Citation8Citation13

Furthermore, the practice of sex determination and abortion of female fetuses has increased rapidly in the past decade, with the last census revealing the lowest-ever sex ratio in India of 927 girls to 1000 boys aged 0–6. Some of the north Indian states, including Rajasthan, are particularly affected.Citation14 The 2001 census revealed that there were only 888 girls to 1000 boys in the district in which this study was undertaken. Fertility decline and the demand for small families, driven by socio-economic and cultural factors, have created additional pressures to have only a desired number of sons.Citation15

A law to regulate fetal diagnostic technology misused for identifying fetal sex, the Prenatal Diagnostic Techniques (Regulation and Prevention of Misuse) (PNDT) Act (1994), states that determining and communicating the sex of a fetus to parents is illegal and that genetic tests to detect fetal defects may only be performed in registered facilities.Citation16 However, enforcement was poor, and activism by several NGOs starting in 2000 led to court orders demanding more accountability from national and state-level health secretaries in implementing the law.Citation17 In 2002, the PNDT Act was amended to limit the use of pre-conception and pre-implantation procedures for sex selection, to require the government registration of ultrasonography providers and to maintain test records by diagnostic centres and doctors. To date, these legislative efforts have been relatively unsuccessful in reducing the practice of sex selective abortion.Citation18 Media efforts have created awareness of the law and community-based studies reveal a high degree of awareness of the illegality of sex determination but tacit acceptance of the practice.Citation10Citation11

The use of information campaigns in public health and reproductive health programmes in India dates from the late 1960s, when community-based government workers used posters, leaflets and radio broadcasts to promote family planning and to inform people about new methods.Citation19 The importance of awareness campaigns that take account of the context and diverse idioms in India has been reinforced in the second Reproductive and Child Health Programme.Citation20

A number of frameworks and methodologies for the evaluation of information campaigns and materials exist,Citation21Citation22 but assessments of reproductive health materials have been limited in India. An unpublished study by the Population Council in 2001–02 found that the materials currently in use by government departments in Andhra Pradesh, Madhya Pradesh and Maharashtra did not facilitate the provision of information on the concept of informed choice of contraception.Citation23 Evaluations of abortion- and sex determination-related materials have been particularly rare. A search of the published literature yielded no studies on abortion-related materials in India and only one study on the content of patient materials for medical and surgical abortion methods in Britain.Citation24

The need for both pre-testing and evaluating information materials is acute given the possibility of misinformation. For example, vague health education messages related to national vaccination programmes have discouraged certain sectors of the population from accessing needed services.Citation25Citation26 The possibility of misinformation is particularly great when communicating messages about abortion and sex determination, topics associated with substantial stigma and a culture of silence.

In an effort to better understand the content, form and quality of existing materials about abortion and sex determination and identify promising practices, the Population Council undertook a small study in one district of Rajasthan. This paper presents our findings, makes recommendations on the content of future materials, and describes a pamphlet we developed on abortion and sex determination, based on our findings.

Methodology

The study is a follow-up to a programme of research on unwanted pregnancy and abortion undertaken by the Population Council in 2001–02 in six districts in Rajasthan, where the need for additional information on materials related to abortion was noted. The pilot study investigated the availability and content of such materials in one of the study districts. The information obtained from the research guided the development of new materials about abortion for use in this region.

The authors selected the study district because of their access to networks of service providers and NGOs working there and available background data on community knowledge and attitudes about unwanted pregnancy and abortion. The district is characterised by low literacy levels, particularly among women, and agriculture is an important source of livelihood. The district is not representative of Rajasthan, hence the findings are merely indicative, with suggestions for future areas of enquiry.

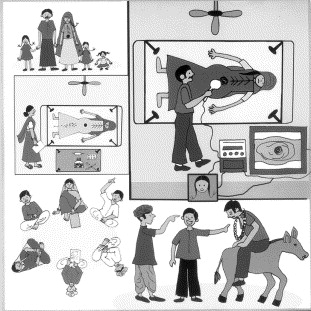

Three different methods were used. First, from May to August 2003, qualitative and quantitative content analysis of information materials about abortion and sex determination in the study district was undertaken, to assess visuals, language and content. Information materials produced, used or distributed in the five years preceding the study (1997–2002) by the state and central government information bureaus and non-profit, NGO and private abortion service providers working in the district were collected in Jaipur. These materials had been distributed locally in the study district either directly by the producers or by a network of NGOs. None of the local NGOs had produced any materials on either of the issues. All available materials related to sex determination, abortion legislation, abortion services, choice of methods and post-abortion complications were examined. Audio-visual materials (audio tapes, video tapes, public service spots and ongoing street plays or performances) and printed materials (pamphlets, wall-charts, picture books and posters/billboards) were included if they offered information or guidance on any of the issues mentioned above. Shop signs and advertisements were not included.

Although every effort was made to collect all available materials, previously-aired television and radio programmes were not easy to access as they were not archived and production managers changed frequently. In addition, insight into the producers' objectives in preparing the materials was limited because production files were not available and those responsible for the development of such materials were often no longer employed.

All materials meeting the inclusion criteria were reviewed using a content checklist and qualitative checklist. Items available in both Hindi and English were checked for consistency of language. Content was assessed using a four-point scale: 0=information not mentioned at all; 1=information implicit though not mentioned directly; 2=explicitly mentioned without repeated mentions or language; 3=explicitly mentioned with repeated mentions or language. For abortion-related material, the content assessed included the legal status of abortion, types of abortion methods available, gestational limits for different types of abortion procedures (medical or surgical), availability, cost and confidentiality of services, details of the abortion procedure (including length of hospital stay, anaesthesia, pre-procedure preparations and potential complications) and post-abortion care issues. The content of materials on sex determination was also assessed using a four-point scale, including the content of the PNDT Act and information promoting positive attitudes towards girl children.

A second checklist was used to assess whether the materials used fear or other motivators, language, text, illustrations and design. The instrument also included questions related to gender sensitivity, links to services and whether the material inspired action and promoted informed choice of methods and services. Each assessment was checked for inconsistencies and differences in interpretation. Results were analysed to identify common themes and significant differences in content, form and style.

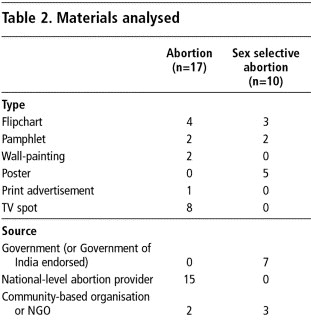

Second, in-depth interviews were conducted with producers and distributors of these materials and abortion providers in the public and private sectors, to understand production and distribution processes (Table 1). The interview sample included four state government officials at the block, district and state levels responsible for the development and dissemination of information material, three print and electronic media representatives working in the state capital Jaipur, and six members of NGO and community-based organisations responsible for production or distribution of materials.

In order to assess the reach and use of these materials, in-depth interviews were also conducted with one provider at the district-level government hospital, two medical officers at block level community health centres, two private providers and one provider at the district-level clinic of a national abortion service provider. All providers interviewed, except one community health centre medical officer offered abortion services.

Third, six focus group discussions were conducted with men and women of reproductive age in villages in two rural blocks and the district headquarters, a semi-urban site, to determine information needs. Each focus group included 8–10 men or women who were recruited with the assistance of a community-based organisation working on water and sanitation, reproductive health and gender issues. Respondents were also shown a purposively selected sample of materials to ascertain what messages they understood from them and if they had seen them before. Respondents were also asked about their media habits, formats in which they would ideally like to see the materials and the content most useful for their needs.

Materials on abortion

We found 17 different materials on abortion (Table 2), of which 15 were produced by one national-level abortion service provider with a clinic in the study district. These 15 materials consisted of flipcharts, pamphlets, wall-paintings, print advertisements and television spots, all produced in 2002. There were also two flipcharts produced by two community-based NGOs, which were being distributed by other NGOs doing community health education in the area. One was produced in 1998 and the other was not dated. Most of the materials were in Hindi and were mostly literacy-dependent. No materials were produced in a local dialect. We found no abortion-related materials at all produced either by the government or by private abortion providers.

The pamphlets and flipcharts of the national service provider were designed for distribution at the clinic or in the organisation's community-based educational activities. Most of the materials used similar design principles and relied on a common pink colour scheme and message format. These were primarily meant as advertising materials about the quality and scope of available services. Most mentioned the location of the service provider's facilities and the legal status of abortion.

One of the flipcharts produced by the national-level provider depicted a clinic in an urban area. The accompanying text advised women: “Always have an abortion done at a registered place by an approved doctor.” Although the flipchart implied that the providers' clinics were approved, the meaning of “registered” was not explained nor how someone could distinguish between an approved and a non-approved provider.

The television spots, print advertisements and wall paintings were meant to provide general information to the public on abortion. Of the eight television spots, three were explicitly on abortion and the rest combined messages on abortion with issues such as contraceptive choice and male involvement. The spots were meant for TV broadcast as well as for narrowcast through mobile video vans. Popular Bollywood film scenes were used to drive home messages on the legality of abortion and access to it. These materials also mentioned the name and location of the provider's clinics. However, like the other materials by this provider, they did not explicitly mention the abortion methods available, time limits or cost.

In contrast, the two flipcharts produced by the community-based NGOs were intended for use in interactive community activities and to communicate more general information about abortion. Both flip charts included colourful line drawings integrating Rajasthani idioms. Each picture in the flip chart was matched with a short narrative paragraph designed to be read by a group facilitator. Both flipcharts were narratives focused on reducing stigma related to abortion and explained the conditions under which a woman could want or need an abortion. They did not make explicit reference to the location of services nor include detailed information on the legal status of abortion, abortion methods or the time limits. Instead, the stories described the abortion-seeking process from a married woman's perspective.

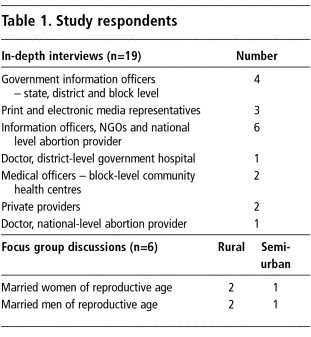

These two flipcharts also used visuals to imply where abortion services were available and the relative safety of different methods. The imagery was either suggestive, where the woman was shown entering a clinic or a dai's (traditional birth attendant) house, or graphic with the woman lying down on a bed and an abortion being performed, either by a trained (with stethoscope) or untrained provider (usually referred to as a dai or depicted as an elderly woman). Both flipcharts pictured a rural setting and were not explicitly linked to a specific service provider. Rather than communicating who could legally seek an abortion, one flipchart implied that a woman should seek an abortion if she was poor or already had three children. None of the 17 materials depicted an adolescent or unmarried woman seeking an abortion or indicated that such a woman could legally obtain an abortion.

All of the materials used the term garbhpaat (abortion) or more colloquial terms such as bachcha girana (to make a child fall), safai (cleaning), unchahe bachche se chutkara (release from an unwanted child). When referring to an unwanted pregnancy, pamphlets used more sanskritised terms such as unnichchit (undesired or harmful) or awanchaniya (unwanted). Less frequently, the colloquial terms bojh (burden), samasya (problem) or galti (mistake) were used in the media spots. While the use of colloquial terms such as bojh or samasya may have made the materials accessible to a broader audience, such words also hold pejorative connotations – used for unwanted girl children, for example – and therefore could be interpreted to condone the practice of sex determination.

Several spots produced by the national-level abortion provider to inform the public of available services suggested that if a woman needed a jaanch (test) of a certain kind, the national-level provider could link her to an appropriate facility. Although the word jaanch is also used to refer to fetal diagnostic tests, the material did not specify the purpose or nature of the test offered.

Materials about sex determination and sex selective abortion

We collected ten different materials about the PNDT Act, sex determination, sex preference or the practice of sex selective abortion (Table 2). The Government of Rajasthan produced five posters and two pamphlets during 2001–2002. Community-based and non-governmental organisations produced three flipcharts, one of these in 1999. Only one flipchart, produced by a community-based organisation, addressed both sex determination and abortion.

We found no radio or television spots related to this topic produced during 1997–2003. However, media coverage of the topic on talk shows and news programmes is quite prevalent, as revealed in the in-depth interviews conducted with producers of the state television network. Nevertheless, many institutions do not regularly or systematically record or archive these programmes so we were unable to include them in our sample.

Most of the materials about sex determination were targeted at families or women. One poster was targeted at doctors offering fetal diagnostic services. The posters and pamphlets produced by the Government of Rajasthan included a detailed description of the content of the PNDT Act and the punishments associated with the Act. The materials were part of a comprehensive campaign initiated in response to the Supreme Court litigation. Two pamphlets and a poster used a similar font, colour scheme and text. Two posters were aimed at doctors. All materials were literacy dependent and in Hindi.

Government materials for both doctors and the public used pejorative terms such as kanya bhrunhatya (murder of the female fetus in the womb) and garbhasthya shishu ka hatya (murder of the infant in the womb) to refer to sex selective abortion. As well as bhrun ki ling jaanch (determining the sex of the fetus), the use of shishu (infant) also appeared, e.g. shishu ki ling jannch (determining the sex of the infant) or ajanme shishu ki ling jaanch (determining the sex of the unborn child). While meant to condemn sex selective abortion, the use of words such as infant or unborn child implicitly equates all abortions with murder and creates confusion about the legal status of abortion.

Posters and pamphlets produced by the government to inform the public about the PNDT Act attempted to discourage sex determination by emphasising that the practice went against established legal and moral codes. Government-produced materials stated that sex determination was gairkanuni (illegal), paap (a sin) and a naitik apradh (moral crime). Posters also included detailed descriptions of the punishments awaiting those who transgressed the law. To reinforce this message, posters and pamphlets used images such as prison cell doors or handcuffs. However, the reference to what was illegal (or who should be placed in handcuffs or in a cell) was vague.

The government posters about sex determination for the general public used visual images to communicate the potential or lost potential of the girl child. One poster showed a picture of a knife cutting a rosebud. Another was more literal and depicted aspirational pictures of women and girls as teachers, doctors, athletes, computer programmers and a farmer driving a tractor. In the corner of this poster was a fetus being squeezed in a fist with the slogan Garbh mein mujh bachchi ko mat maro (Don't kill me, the female child, in the womb).

In general, the posters on sex determination did not distinguish between abortions performed for sex selective reasons and those performed for other reasons (including risk to the health or life of the mother). While the posters implored the audience to make the “right” choice when considering sex determination and sex selective abortion, they did not include information about when a woman may legally have an abortion.

The three flipcharts by the community-based organisations were designed to reinforce the value of the girl child both to an individual family and society. The PNDT legislation was not explicitly mentioned. As with the flipcharts on safe abortion, these flipcharts addressed the issue of sex preference from the perspective of an individual woman. One story concludes with a brief discussion of chromosomes and describes how the sex of a child is determined and says a woman should not be held accountable for the sex of the child she bears.

The production and distribution of materials

Insight into the production and distribution of these materials was obtained from in-depth interviews with government officials, abortion providers and officers in NGOs responsible for materials development and distribution. In general, community-based NGOs had better pre-testing systems and feedback mechanisms in place. Government materials were often produced at the state or central level and distributed to local bodies for dissemination. The central bureaus that produced materials did not have staff or financing to assess and refine existing materials and local bureaus had no support for materials development. At the central and state levels, financing for the development of materials came from vertical disease or topic-related programmes so the government bureaus developed materials covering several issues simultaneously (e.g. polio, leprosy and family planning).

Both governmental and non-governmental groups out-sourced the design process; however, NGOs appeared to have exercised greater editorial control. NGOs also had longer-term communication objectives and, at least in theory, conceived of abortion-related materials within a broader reproductive health programme.

As regards dissemination, in the public sector, district-level information bureaus located in the Chief Medical Health Officers' department were responsible for dissemination of materials at the block level, where materials were meant to be displayed at the village panchayat's (leader's) office and community health centres. In one district, the officer said that materials were often not disseminated at the community level because of budgetary and logistical problems. Lack of jeeps to reach rural areas meant that materials often lay unused in government stock houses, or were only distributed in easily accessible areas. Community-based NGOs produced materials on a much smaller scale than the public sector. However the community-based NGOs also reported limited financial resources for dissemination. Similarly, they reported difficulties in circulating materials and obtaining feedback.

In our view, abortion providers' commercial interests and desire to maintain confidential services limited the distribution and development of materials. Interviews with abortion providers working in the private, NGO and public sectors revealed ambivalent attitudes towards public information campaigns and advertising. One provider in private practice said in most cases women came through word of mouth and she felt no need to advertise. The doctor at the district level clinic of the national-level service provider saw the need for materials to motivate people to “make the right choice” with regard to issues such as family planning, while providers working in both the public sector and private practice felt information campaigns had a limited effect on women's reproductive choices.

The opinions of government officials may also influence the community's access to and interpretation of messages about abortion and sex selective abortion. Government officials interviewed were clearly confused about the legal status of abortion and the content of the PNDT Act. One block health supervisor (responsible for dissemination of government materials at the local level) said: We tell people abortions are wrong. The block health supervisor in another district elaborated further: Abortions are illegal. There is a law against them and they should not take place… Abortions take place only after sex determination, not otherwise.

Although our sample size is small, these comments suggest that the opinions of those responsible for disseminating and displaying information about abortion and sex determination may shape the availability and the interpretation of materials on abortion.

What did local people want to know about abortion and sex determination?

Focus group respondents said they needed information about the location of safe abortion services and the number of weeks of pregnancy at which women could obtain services. Women wanted to know where and from whom a safe abortion could be obtained. After viewing two flipcharts on abortion, one woman noted: Now we know that we should go to a trained doctor only.

However, respondents also pointed out that a trained provider was not available in their area and thus such information served a limited purpose. After viewing the flipchart created by the national-level abortion provider, some men and women were confused about who qualified as a registered provider or what constituted an approved facility. One man understood the term “registered” to mean that services were available free or at low cost.

Women, men, providers and communications officers from both private and public identified a need for information in simple, comprehensible language. After viewing several posters about abortion and sex selective abortion, one woman commented that the material was difficult to understand because: This is not the language of the village.

Several women said that materials should not imply that male involvement is required to obtain abortion services. These women noted that while images of men accompanying women for abortion services were accurate in some instances, both married and unmarried women might seek an abortion without the knowledge of their partner. Indeed in some cases, male involvement may not constitute support but coercion. In one focus group, when discussing sex selective abortion, women underscored that a “husband should not compel a woman to abort” and posters should communicate this message to men.

Respondents also identified the need for materials directed at adolescents and unmarried women.

“It is okay … telling us not to do sonography and abort a female. But what about boys and girls in college who develop love for each other and the girl gets pregnant? It tells us nothing about what she can do.”

Men reiterated the need for messages to target older family members, given their important role in shaping social norms around abortion and sex preference. One man explained how a couple may wish to conceal an abortion from senior family members and thus seek services from a clandestine provider. He felt that informing senior members about the legal status of abortion may help to reduce the stigma associated with it. Women felt that materials related to sex preference should specifically target senior family members as well.

The focus group discussions provided insight into some of the challenges in producing materials about abortion and sex determination. The respondents were often confused about the legal status of abortion after viewing the materials on sex determination and abortion. In some cases, the vague messages in some of the PNDT materials, coupled with ambivalence about the acceptability of abortion, also appeared to compound confusion about the legal status of abortion. For example, after seeing a government poster on punishments under the PNDT Act, one man believed the poster was useful: …as it communicated that one should not have an abortion as it is “killing a fetus”. Another man, having seen the government material on sex selective abortion said: Abortions are illegal. Both after sex determination and without sex determination. If a young bud is knifed through, then we have crushed her future. He believed that all abortions were performed for sex selective reasons. Thus he felt that: If there is no sex determination, there will be no abortions. Abortions only take place after sex determination.

One woman hinted at some of the unintended consequences of the campaign against sex determination: The law was not always there. First there used to be safai (abortion)… But it was not so hidden. Now that there is a control on it, people do it covertly. Now sex determination is done and abortions take place secretly.

That said, in focus groups both men and women expressed their skepticism about the ability of communication materials to change gender norms or behaviour, particularly in the absence of other measures, such as more stringent implementation of the law, and particularly related to sex preference. The men thought the posters posed little deterrence to the practice of sex determination, particularly given the absence of formal records of the procedure:

“Even those who do ultrasound, they too have posters up saying that this is illegal. But they do it and they don't give a receipt.”

“These handcuffs [in the PNDT poster] have not been put on anyone, they have been put only in posters.”

Mixed messages: legal abortion and illegal sex determination

This was a small study in one district in Rajasthan. The results are largely exploratory, but suggest the urgent need for changes in the messages about the PNDT Act and the development of new materials. Our sample of materials may not have been comprehensive; there were likely to be radio and television spots we did not see. Nor did we study whether the availability, content and tone of messages had changed over time. Given regional differences in the practice of sex selective abortion and the implementation of the PNDT Act, the influence of the PNDT campaign is likely to vary as well.

Nonetheless, the study did find an absence of informational material about safe abortion in both the public and private sectors in the study district. Only a single national-level abortion provider produced materials about abortion. Although a significant contributor to maternal mortality, abortion was also not included in conventional safe motherhood materials created by the public or non-governmental sectors. Clearly, the public sector should make a concerted effort to include abortion in safe motherhood education campaigns as well as develop campaigns to inform the public about the legal status of abortion in India.

Almost all the materials about sex determination were available from the public sector and media and did not include any information about legal abortion. The majority were probably produced in order to comply with the PNDT Act, after a Supreme Court order to state governments to do so. Many of the materials about sex determination produced by the Ministry of Health and Family  Welfare used vague or complicated language and employed negative or fear-inducing imagery. There were several instances where messages about the legality of abortion services and the illegality of sex determination were confused. Some failed to distinguish between abortion for reasons of sex selection and other reasons, thus implying that all abortions were illegal or immoral.

Welfare used vague or complicated language and employed negative or fear-inducing imagery. There were several instances where messages about the legality of abortion services and the illegality of sex determination were confused. Some failed to distinguish between abortion for reasons of sex selection and other reasons, thus implying that all abortions were illegal or immoral.

We recommend that future informational materials should address the issues of abortion and sex determination simultaneously, including the legal status of abortion, the availability of abortion services and providers, and the social norms that shape decision-making on abortion. Materials should include adolescent and unmarried women and help women and their families identify legal and safe abortion providers. Materials should acknowledge that the decision to seek abortion services involves the participation of family members while empowering women to make independent decisions. Finally, campaigns should be sensitive to the issue of sex determination and sex selective abortion, and clarify the conditions under which a woman can and cannot seek an abortion.

Future efforts should communicate these complex messages while avoiding legalistic or technical language. Greater involvement of local-level actors and local women's groups may help to make new materials more responsive to local conditions and idioms. Most of the materials identified were entirely literacy dependent and thus inaccessible to the non-literate. Innovative methods and media for communicating information should be used, rather than rely solely on the written word. Generally, men and women felt information about abortion should be communicated through inter-personal communication materials, while messages about sex selective abortion could be better addressed through the mass media. These preferences should be given careful consideration. Limiting abortion-related communication to inter-personal methods could further stigmatise the issue. Similarly, relegating sex selection-related communication to the wider media would make it easier for people to deny the very existence of the phenomenon in their families and community. Addressing both topics through different media may reduce the shame and stigma associated with abortion and raise awareness about gender discrimination.

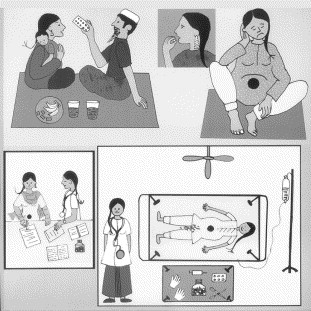

From research to action: production of information materials for low-literate women

The findings of this study informed the production of information materials specifically designed for low-literate women in the study district, but also for use in northern India where Hindi is understood. The materials include a manual for local health educators and trainers and a booklet for women, both entitled Safai Ki Jankari (Information on Abortion), illustrated with a visual grammar understood by low-literate audiences. The manual is a four-fold book that opens out like the petals of a flower. One side has four stories represented pictorially – each featuring a different woman – depicting their motivation for and experiences of seeking an induced abortion. The centre panel illustrates the stages of pregnancy and the legal limits of abortion in India. The other side of the manual has text, telling each woman's story. The centre panel on that side has information on the legality of abortion and describes how to use the booklet. The text is meant to be read out by the educator in health promotion sessions. The booklet for women is palm-sized and can be handed out to participants at the end of the session. The booklet contains the same information as the training manual. In addition there is an empty space where the health educator can provide information on local, safe, registered abortion services. The language used is simple and free of jargon.

The research described in this paper helped us to develop an ideal list of key messages for future materials on abortion and sex determination. These included the importance of correct information about the abortion law, choosing registered and safe providers, seeking abortion as early as possible, messages for adolescents, information on post-abortion care and the illegality of sex determination. Given the confusion in people's minds about the legality of abortion and the illegality of sex determination, we felt it was important to address the two issues together in one booklet.

The new materials were designed by a graphic artist, Ms Lakshmi Murthy (<www.vikalpdesign.com>), who has experience in developing media materials for low-literate women in a visual idiom that they understand (see illustrations). As part of the MacArthur Foundation's Leadership Development Programme in India she had created a lexicon of images on reproductive health drawn by low-literate women in rural Rajasthan and tested these in several other rural areas in India. Examples of visual imagery used and understood by low-literate women include a black dot to represent pregnancy, an inverted ‘u’ to represent the uterus and visualising inner spaces, such as houses, from a flat perspective rather than a three-dimensional perspective as is common in more urban visual sensibilities.

We tested these images in our study district to assess whether they were understood and could be used in the context of abortion. Focus group discussions also gave us the opportunity to add to the lexicon – specifically images on abortion and stages of pregnancy as drawn by women. These discussions also gave us an opportunity to gather women's narratives about abortion.

In the process of designing these materials we encountered some difficulties, which we feel should be taken into account while communicating messages on safe abortion. For example, women did not understand the concept of a registered and legal provider and expressed more interest in getting information on a safe abortion provider. In their words a provider had to be sahi (true). This posed a challenge for us as we could not advocate for “safe/true” providers rather than “legal/registered” ones – the language more  accepted in the legal framework. As a compromise we use the phrase “safe providers, recognised as such by the government of India”.

accepted in the legal framework. As a compromise we use the phrase “safe providers, recognised as such by the government of India”.

We also found it very difficult to create materials that were purely visual. As a solution we created the manual to be used by educators and trainers in NGOs and the booklet that women could take away from sessions on reproductive health. While this limited our audience, we felt it was a necessary compromise if we wanted to communicate correct information on both issues together. It is hoped that women will be able to share what they learn in these sessions with others in their households and neighbourhoods, and will be encouraged to do so.

This set of materials on abortion has been widely distributed in India through a network of NGOs working in Hindi-speaking areas of the country. (Copies from <[email protected]>)

Acknowledgements

We are indebted to Neera Kashyap, who was part of the study team, and who contributed significantly to the analysis. We would like to thank Bela Ganatra, Shireen Jejeebhoy and Batya Elul for their comments on various drafts of this paper. An earlier version of the paper: “Mixed messages? An analysis of communication materials on abortion and sex determination in Rajasthan” appeared in Economic and Political Weekly 2005;90(35):3856–62. We thank the editor, C Rammanohar Reddy, for permission to publish this revised version. The John D and Catherine T MacArthur Foundation provided financial support for this project.

References

- L Visaria, V Ramachandran, B Ganatra. Abortion in India: Emerging Issues from the Qualitative Studies. 2004; Center for Health and Allied Traditions: Pune.

- R Chhabra, SC Nuna. Abortion in India: An Overview. 1994; Veerendra Printers: New Delhi.

- Government of India. The Medical Termination of Pregnancy Act. Act No. 34, 1971.

- Government of India. The Medical Termination of Pregnancy Act (amendment) bill. Bill No. XXXV, 2002.

- Government of India. The Medical Termination of Pregnancy Rules (amendment), 2003.

- ME Khan, S Barge, N Kumar. Abortion in India: current situation and future challenges. S Pachauri. Implementing a Reproductive Health Agenda in India: The Beginning. 1999; Population Council: New Delhi, India.

- HB Johnston. Abortion Practice in India: A Review of the Literature. 2002; Centre for Enquiry into Health and Allied Themes and Research Centre for Ansundhan Trust: Mumbai.

- BR Ganatra. Induced abortions: programmatic and policy implications of data emerging from an ongoing study in rural Maharashtra, India. C Puri, P Van Look. Sexual and Reproductive Health: Recent Advances, Future Directions. 2000; New Age International: New Delhi, India.

- Indian Council of Medical Research. Illegal Abortion in Rural Areas: A Task Force Study. 1991; ICMR: New Delhi.

- B Elul, S Barge, S Verma. Unwanted Pregnancy and Induced Abortion: Data from Men and Women in Rajasthan. 2004; Population Council: New York.

- A Malhotra, L Nyblade, S Parsuraman. Abortion and Contraception in India. 2003; ICRW: Washington D.C.

- Registrar General of India. Sample Registration System, Statistical Report. 2004; Office of the Registrar General: New Delhi.

- M Sood, Y Juneja, U Goyal. Maternal mortality and morbidity associated with clandestine abortions. Journal of the Indian Medical Association. 93(2): 1995; 77–79.

- Registrar General of India. Census of India, Provisional Population Totals, I. Series, Paper I. 2001. 2001; Office of the Registrar General: New Delhi.

- M Das Gupta. Explaning Asia's “missing women”: a new look at the data. Population and Development Review. 31(3): 2005; 529–536.

- I Jaising. Pre-Conception & Prenatal Diagnostic Techniques Act: A Users Guide to the Law. 2004; Universal Law and Publishing: New Delhi.

- R Mallik. A less valued life: population policy and sex selection in India. 2002; Centre for Health and Gender Equity: Takoma Park, MD.

- S George. Sex selection/determination in India: contemporary developments. Reproductive Health Matters. 10(19): 2002; 190–192.

- P Piotrow, DL Kinkaid, J Rimon. Health Communication: Lessons from Family Planning and Reproductive Health. 1997; Praeger: Westport, CN.

- Ministry of Health and Family Welfare. Reproductive and Child Health II and Family Planning Programme Implementation Plan. New Delhi: Department of Family Welfare, MOHFW, 2003. (Draft)

- T Kane, M Gueye, I Speizer. The impact of a family planning multimedia campaign in Bamako, Mali. Studies in Family Planning. 29(3): 1998; 309–323.

- DL Kincaid, A Merrit, L Nickerson. Impact of a mass media vasectomy campaign in Brazil. International Family Planning Perspectives. 22: 1996; 169–175.

- Population Council. Analysis of IEC on expanded and informed contraceptive choice, 2002. (Draft report)

- S Wong, H Bekker, J Thornton. Choices about abortion method: assessing the quality of patient information leaflets in England and Wales. British Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology. 110: 2003; 263–266.

- M Nichter. Vaccinations in the Third World: a consideration of community demand. Social Science and Medicine. 41(5): 1995; 617–632.

- MS Singh. Bharadwaj 1995. Communicating immunisation: the mass media strategies. Economic and Political Weekly. 2(19–26): 2000; 667–675.