Abstract

Family planning was once a sensitive issue in Indonesia, but today it is considered essential. This paper reports on a study in 1997–98 of the role of village family planning volunteers and the cadres who worked under them in West Java, Central Java and DI Yogyakarta, in implementing the national family planning programme in Indonesia. A total of 108 village family planning volunteers, 108 family planning cadres, 108 local leaders and 324 couples eligible for family planning from 36 villages in the three provinces were interviewed. The volunteers and cadres have made a significant contribution to the implementation of the family planning programme. They promote family planning, organise meetings, provide information, organise income-generation activities, give savings and credit assistance, collect and report data and deliver other family welfare services. Teachers, wives of government officials and others recognised by the community as better off in terms of education and living conditions were most often identified to become family planning volunteers. Because they are women and because they are the most distant arm of the programme, their work is taken for granted. As their activities are directed towards women, especially in women's traditional roles, the programme tends to entrench the existing gender gap in responsibility for family planning and family welfare.

Résumé

La planification familiale était jadis une question sensible en Indonésie, mais elle est aujourd'hui jugée essentielle. Une étude, menée en 1997-98 à Java occidental, Java central et DI Yogyakarta, a analysé le rôle des bénévoles villageois de planification familiale et des cadres qui ont travaillé sous leur direction dans l'application du programme national de planification familiale en Indonésie. Elle a interrogé 108 bénévoles villageois et 108 cadres de planification familiale ainsi que 108 décideurs locaux et 324 couples pouvant prétendre aux services de planification familiale de 36 villages dans les trois provinces. Les bénévoles et les cadres ont fait une contribution importante à la réalisation du programme. Ils encouragent la planification familiale, organisent des réunions, distribuent des informations, créent des activités rémunératrices, apportent une aide pour l'épargne et le crédit, recueillent et transmettent les données et assurent d'autres services de protection familiale. Le plus souvent, ce sont des enseignantes, des épouses de fonctionnaires et d'autres personnes jugées plus instruites ou plus aisées par la communauté qui ont été choisies pour devenir bénévoles. Parce que ce sont des femmes et qu'elles sont le bras le plus éloigné du programme, leur travail semble aller de soi. Comme les activités sont axées sur les femmes, particulièrement dans les rôles féminins traditionnels, le programme tend à conforter l'écart existant entre les sexes dans la responsabilité de la planification familiale et du bien-être de la famille.

Resumen

Antes un tema delicado en Indonesia, la planificación familiar (PF) es considerada esencial hoy en día. En este artículo se informa de un estudio realizado en 1997–98 de la función de los voluntarios de planificación familiar y los sub-voluntarios bajo su mando en Java Occidental, Java Central y DI Yogyakarta, en la implementación del programa nacional de PF en Indonesia. Se entrevistó a un total de 108 voluntarios comunitarios en PF, 108 sub-voluntarios en PF, 108 líderes locales y 324 parejas elegibles para la PF provenientes de 36 poblados en las tres provincias. Los voluntarios y sub-voluntarios han ayudado en gran medida a implementar el programa de PF. Ellos promueven la PF, organizan reuniones, proporcionan información, organizan actividades para generar ingresos, brindan ayuda con ahorros y crédito, recolectan e informan datos y proporcionan otros servicios para el bienestar de la familia. Los maestros, las esposas de los funcionarios gubernamentales y otros reconocidos por la comunidad por estar en mejor posición en cuanto a su formación y condiciones de vivienda, fueron señalados con más frecuencia como buenos candidatos para ser voluntarios en PF. Por ser mujeres y el brazo más distante del programa, su trabajo no es valorado. Dado que sus actividades están dirigidas hacia las mujeres, especialmente en sus papeles tradicionales, el programa tiende a afianzar la brecha actual entre sexos en la responsabilidad de PF y el bienestar de la familia.

The Indonesian National Family Planning Coordinating Board (BKKBN) was formed in 1970 during the government of President Soeharto, who did not initially consider family planning an important issue. He was more concerned to develop an internal migration programme, to encourage Indonesians to move to the outer Javanese islands and develop settlements in designated areas. Later, Soeharto was convinced by technocrats and donors that family planning should be introduced to the conservative Indonesian community. His first step in this regard was to sign the United Nations-sponsored World Leaders' Declaration on Population in December 1967, followed by a public statement the following year that family planning would receive the “aid, support and protection of the Government”.Citation1

President Soeharto's support, and that of medical practitioners and others, transformed how Indonesians saw family planning. Family planning was once considered a forbidden practice and a sensitive issue, but today it is considered essential. The BKKBN and Indonesian Planned Parenthood Association have played a major role in this regard over the past 30 years, and a major transition has occurred. Before the 1960s the average number of children was six; it is now only two or three. Children are not seen as status symbols or as a human resource for agrarian families. Nearly all Indonesians now believe that a small family is preferable. Today, more than two-thirds of all Indonesian couples have used some form of modern contraception, and more than half continue to do so.Citation2Citation3Citation4 In 2002–03, use of modern methods of birth control among women in Indonesia was still heavily based on female methods (55.2%) as compared to condom use (0.9%) or male sterilisation (0.4%),Citation4Citation5 and responsibility for family planning still rests heavily on women, alongside domestic duties, childbearing and childrearing.Citation6

Strategies for changing behaviour in traditional societies using, for example, extension workers or community-based volunteers have been quite successful in agriculture, environmental issues and other health and community development programmes.Citation7 Community-based family planning distribution programmes were started in Asia in the 1960s in Indonesia, Korea, Taiwan and Thailand and spread throughout Asia (and in Latin America) in the 1970s and 1980s.Citation8Citation9Citation10

Descriptive studies have found that family planning volunteers and cadres have played a significant part in the success story of family planning and fertility decline in Indonesia.Citation1Citation2Citation3Citation4 Since the late 1970s, they have been the grassroots unit in the community that promotes, records and provides family planning and family welfare related services.Citation11Citation12Citation13Citation14Citation15 In the first decade of the family planning programme, the main role of family planning field workers, who are employed by BKKBN, was to make the first contact with eligible couples of reproductive age and disseminate family planning information to them. In the 1980s their job description changed. They were made responsible for educating, training and supervising family planning volunteers and cadres, who then became the ones to make initial contact with eligible couples. They were to provide information and motivate ever-married women to use family planning and participate in various voluntary groups, e.g. for pregnant and lactating women, children under five, parents of teenagers and the elderly, as well as income-generating group activities. This role makes them quite prominent in the community. The 1997 Indonesian Demographic and Health Survey found that in rural areas, women's groups (50.8%), village leaders (50.2%), community leaders (43.8%) and religious leaders (38.5%) were regarded by ever-married women as appropriate sources of family planning information.Citation3 Most of these leaders and groups were and remain strongly linked to family planning volunteers and cadres.

In 1993, there were more than 66,000 villages in Indonesia, 90% of them rural. In each sub-village there were at least ten village volunteers working to promote family planning without receiving any payment.Citation16 Yet the role of these volunteers and the cadres who work under them has been under-researched. We therefore carried out a study, sponsored by the BKKBN, on how the state has fashioned and tailored the role of village family planning volunteers and cadres in implementing the national family planning agenda from three dimensions: responsibility and status within the national family planning programme goals, the volunteers' perspectives and a gender perspective.

Methodology

Survey data were collected in January 1997–December 1998 and field observation continued into 1999 in West Java, Central Java and DI Yogyakarta, where family planning volunteers mostly work independently. In each province, two districts were purposively selected with the criterion that the family planning volunteers in that district can mostly work independently, two sub-districts from each district were then randomly chosen and in each sub-district, nine villages were selected randomly. Thus in each province, 36 villages were selected. There were 648 respondents interviewed consisting of 108 village family planning volunteers, 108 family planning cadres who were responsible for organising various community-level group activities, 108 informal or religious leaders, and 324 couples eligible for use of family planning. All of the family planning volunteers and cadres in the three areas studied were women.

A structured questionnaire was designed for the village family planning volunteers and eligible couples, and a more open-ended interview schedule was designed for the cadres and informal leaders. The survey questionnaire covered demography characteristics of the respondents, training and roles of the family planning volunteers, legal status, job descriptions and conduct of meetings. The in-depth interviews aimed to collect information on the volunteers' perspectives and views regarding their roles.

Observation and informal interviews were also conducted in each of the villages where the study took place. The quantitative data were analysed using SPSS for Windows, and the interview data were analysed qualitatively to give a more holistic view on how the village volunteers and cadres committed themselves to the successful implementation of the family planning programme, especially in an era of economic crisis.

“As soon as I know that someone in my village has just married, I approach the newlywed wife, ask her to participate in our activities and promote family planning for her future use. If any of my neighbours or villagers has problems related to pregnancy, birth or contraceptive use, then I will be contacted. I will then visit them in their home, talk to them and assist them to get the appropriate health services. This can be by visiting the sub-district Community Health Centre… I enjoy being a family planning cadre. My group activities also include income-generating groups producing marketable, embroidered clothes for children, and cassava chips.”

Responsibilities and status of village family planning volunteers nationally

Volunteers were expected to fulfil six main roles:

| • | manage and work as a group with their fellow village cadres; | ||||

| • | attend and organise meetings on a regular basis, including meetings with other sectors in the village and meetings with sub-village cadres; | ||||

| • | provide information, education, awareness-raising and counselling; | ||||

| • | implement strategies to promote economic self-sufficiency, including income-generating groups, and savings and credit assistance. | ||||

| • | administer data collection and management; and | ||||

| • | deliver family welfare services, including family planning services for condom and pills, advice on medical assistance, services for families with elderly members, children under five and adolescents.Citation17Citation18Citation19Citation20 | ||||

Volunteers were usually also expected to perform other village-level roles, e.g. the running of the weekly and monthly community-run services in sub-village integrated health posts (Posyandu) for baby weighing, immunisation, family planning, the nutrition programme and diarrhoea control.

Income-generating groups, promoted since 1979, were mainly to be based on home-industry activities. Most income generating groups in the villages studied in West Java produced savoury chips from cassava and sticky rice. Other products included embroidery for children's clothes and customary Muslim clothes. The BKKBN would provide funds to be used by groups of women who accepted family planning. The group could decide how to use the funds, who was eligible to borrow money, interest rates and how the capital was managed. The idea was that all group members would learn a skill, then produce and sell a product. The cadre responsible for managing the group would undertake training provided by the Department of Industry and would then train other group members. Groups would also carry out other fund-raising activities such as saving a handful of rice each day to contribute to the members of the group who were in need.Citation16

Volunteers were treated as though they were employed by the BKKBN and were expected to operate effectively. This was measured by whether family planning services were provided satisfactorily, whether they were operating with their own funding and the extent to which group activities had been initiated. Activities that were monitored and evaluated included work plans and whether meeting notes were recorded. This increased the pressure and the burden upon them, though most were not highly educated. In 1993–94, a family planning field worker had to attend about 20 coordination meetings per year.Citation21 On the other hand, paid family planning field workers relied heavily on the work of family planning volunteers.

Of all the duties assigned to the village family planning volunteers, data collection and recording of family planning and family welfare matters were the most difficult, time consuming and costly. These data were later processed and analysed by the BKKBN and published as national data. Often due to limitations of supply, the recording forms provided by the BKKBN had to be copied at the expense of the volunteers. Volunteers were also required to meet the costs of their own transport to attend meetings at the village and district level and to contribute to family welfare activities, in the form of money, rice, preparation of food for children under five, school children and pregnant women, as well as time and effort.

The institutionalised message being conveyed was that the BKKBN was empowering women by providing them with responsibilities for promoting family planning, collecting data for national and economic development and helping to implement the national family welfare ideology. The women were supervised, monitored and provided with training so that they could perform their duties efficiently but also so that they would be rewarded with non-monetary social status.

Teachers, wives of government officials and others recognised by the community as better off in terms of education and living conditions were most often identified to become family planning volunteers. Wives of government officials were also often pressed to participate as family planning volunteers and made to feel ashamed if they did not.Citation19 In the first instance, the women were drawn very largely from a group known as KB Lestari, literally stars of family planning, women who were long-term contraceptive users who had not had a child for 5–16 years, and who were rewarded with a certificate and a medal. For those residing in the village, two coconut tree seedlings of a special hybrid that bears fruit rapidly and at a low height were also given. The trees were often planted at the front of their houses for display and social recognition, while the certificate was framed and hung in the living room and the medal worn by the winner at social gatherings and functions. A very prestigious reward was the appreciation given to KB Lestari couples on National Family Day or Independence Day at the Presidential Palace. KB Lestari winners were brought to the palace to receive the award in a special ceremony broadcast nationally, and the couple would wear a special traditional costume representing their province.

Thus, before beginning their role as volunteers, the women had received social recognition in relation to family planning. Moreover, the village head recognised their role as a valuable one, and they were invited to village meetings, another source of social status. Other women in the community aspired to the status and prestige of those who received such awards. The aim was to create a situation in which every woman of reproductive age and older wanted to be part of this group.

Village family planning volunteers in West Java, Central Java and DI Yogyakarta

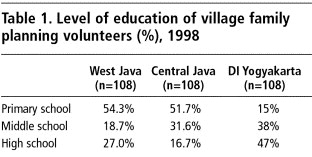

Volunteers in DI Yogyakarta had the highest level of education compared to the other provinces (Table 1). The majority of volunteers in West Java (86%) were not involved in paid work as they were mostly the wives of village heads. In Central Java, on the other hand, village family planning volunteers were mostly village officers who managed a piece of land provided by the village (tanah bengkok). Income from the land could be used by the family planning and family welfare groups as a source of funding, which could be economically rewarding for a family planning volunteer. Only 33% were not in paid work, while in DI Yogyakarta 30% were not in paid work.

There were two types of organisational structures for family planning volunteers: collective with a chief, secretary and treasurer, or individual, i.e. only one family planning volunteer. The volunteers in Central Java and DI Yogyakarta mostly worked as individuals and were representatives of the community. Seventy-five per cent of the volunteer selection process was accomplished through an open selection discussion during village meetings. Where there was collective organisation, the officers' positions in Central Java and DI Yogyakarta were difficult to fill as cadres who would take on the responsibility were hard to find. The situation was different in West Java because the volunteers occupied a more formal place in the village organisation. As the wives of village headmen, they would organise a group of women to be responsible for different kind of duties, including family planning and family welfare.

In total, 80% of the volunteers had received some form of training. In the three months before the study, 75% of the volunteers in DI Yogyakarta had received training while only 47% in Central Java and 43% in West Java had received training. Most of the training was about information, education and communication in family planning and family welfare and the operation of sub-village integrated health posts.

The great majority of participants in the study agreed that the village family planning volunteers and cadres significantly contributed to the implementation of the family planning programme. The eligible couples and formal and informal leaders all agreed that the volunteers were capable of helping the village administrator and villagers to obtain information and assistance relating to family planning, access to family planning methods as well as conducting family welfare group activities. The significant role of the village volunteers was socially recognised and they were always invited to the monthly village coordinating meeting and asked to give advice when the village had problems relating to family planning and health.

Village officials as compared with village informal leaders were more involved with village family planning volunteers as they often coordinated village activities together. Those involved in group activities were mostly women with children under five. This is strongly related to the fact that the volunteers first became connected with the women through the provision of contraceptive methods and health services referrals. Savings and credit groups were mostly not under the management and supervision of the village family planning volunteers but directly under the supervision of family planning field workers. Thus, cadres responsible for these groups reported directly to the family planning field workers, while communication and coordination with the village family planning volunteers was less likely.

The village family planning volunteer was defined by the BKKBN as the chief who managed several cadres who were in turn responsible for family welfare activities. Consequently, the work of the chief family planning volunteer and the cadres was expected to be collaborative, with each inspiring the other. When asked whether they were coordinating and monitoring village family planning cadres responsible for family welfare group activities, 72% of volunteers in DI Yogyakarta and 64% in Central Java said they were performing this task, and 53% in West Java.

Where the work relationship was not collaborative, qualitative data revealed that the dual leadership role and competitiveness between the family planning field workers, who were BKKBN employees, and the village family planning volunteers was problematic at times. In fact, in some cases the family planning field workers, who were supposed to be the managers of family planning programmes at the village level, seemed to be interfering with the village family planning volunteers' responsibilities. In this situation, savings and credit groups were most likely to be developed under the supervision of family planning field workers. Moreover, if an income-generating group began producing good economic returns, it seems that the management responsibilities were removed from the village family planning volunteers. Other cadres who were less likely to coordinate with the village family planning volunteers were those working on services for families with children under five.

In all three provinces, information, education and communication seemed to be the strongest role perceived by the family planning volunteers besides their role in data recording and reporting. Only four family planning volunteers in DI Yogyakarta did not perform these roles. Volunteers most often used group forums to promote family planning. Indeed, most of the volunteers reported that they only saw information and education provision, data collecting and reporting, and being able to generate sufficient funding as roles that were important to achieve. Three-quarters of the volunteers provided contraceptive services, savings and credit assistance and referral advice for health care. Qualitative data revealed that the volunteers in West and Central Java, as compared to DI Yogyakarta, did not seem to invest as much effort on these family welfare activities. The other roles outlined earlier, expected by the BKKBN, were not always well understood by the volunteers nor did they always perform all of these roles. In many cases the volunteers not only did family planning promotion but also as a health cadre.

The family planning volunteers commonly did not organise their activities based on written work plans or guidelines. Initiatives were inspired by meetings or at the instruction of the wife of the village head. Routine activities were said to be conducted year after year in the same way. The meetings were conducted every 40 days (selapanan) in the village community centre, except in DI Yogyakarta where they were usually conducted at the hamlet level. In these meetings, other cadres also participated, including those from the Prosperous Family Empowerment Movement and integrated health posts. The meeting agenda included matters related to the neighbourhood lottery (arisan), talks given by the wife of the village head or other cadres related to health, family planning, healthy environment and herbal gardens. Problems encountered by volunteers and services provided by cadres were usually not discussed.

Surprisingly, the economic crisis did not have a large impact. Although the funding from the community to conduct activities for eligible couples, children under five, adolescents and the elderly became more restricted, couples still purchased contraceptive methods, as family planning had become a way of life. To overcome any limits on funding to conduct group activities, the volunteers approached people in the village for contributions.

The monthly data collected by volunteers were passed on to the paid family planning field workers who, in turn convey the information to BKKBN in Jakarta. These data are used officially by BKKBN and other sectors to describe family planning use in Indonesia. Other sectors rely on these data as they are the only national data available. However, even though nearly every family planning volunteer collects and records family planning and family welfare data, the quality of the data must be questioned. The forms that the sub-village family planning volunteers and village family planning volunteers had to complete on a monthly basis were not at all easy, given the relatively low levels of education among many of them. These volunteers also had to complete the forms for other activities such as with young families, families with children under five, adolescent children and elderly relatives. Thus, the data collection process was complicated. In cases where shortages of forms were experienced, the cadres had to copy the forms from their own sources of funding.

That family planning volunteers and cadres enjoyed their work was seen in their dedication to their roles. In all three provinces, the large majority of volunteers said they were satisfied and happy to be involved with the task, in Central Java 88.9%, West Java 80.6% and DI Yogyakarta 86.1%. Regardless of whether they were appointed or had volunteered, the majority were happy and proud of their work. In DI Yogyakarta, the volunteers, regardless of their multiple roles, were very proud of their family planning promotion role while in West and Central Java, they were more proud to be volunteers for the Integrated Health Post or the Prosperous Family Empowerment Movement. It was evident from field observation that family planning volunteers and cadres were well integrated into other social activities in the community.

Perspectives of couples eligible for family planning

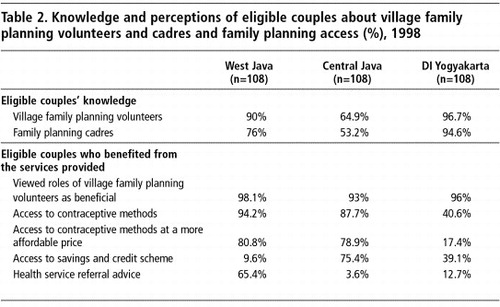

Table 2 shows the perspectives of those eligible for family planning. More eligible couples in DI Yogyakarta and West Java knew about the village family planning volunteers and cadres and the group activities in their area, as compared with those in Central Java. There were more eligible couples in DI Yogyakarta (90%) involved in group activities as compared to Central Java (75%) and West Java (58%). The proportion of women in eligible couples who were themselves village family planning volunteers was lowest in West Java, where the volunteer conventionally was the wife of the village head. In Central Java (48%) and DI Yogyakarta (38%) the proportion was high.

Table 2 Knowledge and perceptions of eligible couples about village family planning volunteers and carders and family planning access (%), 1998

In general, almost all of the eligible couples surveyed thought that services provided by village family planning volunteers were beneficial (more than 90% in all study villages) but among those in DI Yogyakarta, when asked about specific services, fewer said yes. For example, as regards access to contraceptive methods only 41% were satisfied, and even fewer as regards access to more affordable contraceptive methods (17%), access to savings and credits schemes (39%) or receiving health service referral advice (13%). Eligible couples in Central Java benefited most from the savings and credit schemes (75%) but were the least likely to get health services referral advice (4%). Eligible couples in West Java were least likely to have access to a savings and credit scheme (10%) but more likely than those in Central Java to get health services referral advice (10%).

A gender perspective on the volunteers' roles

Whether or not formal and informal leaders understood the roles of village family planning volunteers depended strongly on their work relationship with the volunteers. If they were engaged in community activities, then both the formal and informal leaders' understanding of the village family planning volunteers' responsibilities and roles was more apparent. In general, the formal and informal leaders interviewed had very positive views of the village family planning volunteers' role as mediators between the community and village leaders. The village family planning volunteers were also perceived as having a beneficial impact upon the community.

However, formal and informal leaders, mostly men, also had a fixed idea that family planning and health care responsibilities were women's domain. This is problematic, as formal and informal leaders are prominent in shaping the perceptions of community members as to what is expected from women and men regarding reproductive health and family and community care. For this reason, the volunteers programme has had the effect of institutionalising reproductive and family and community care roles and responsibilities within the sphere of women.

The socialising process strongly emphasises that women's roles are in the domestic sphere, childbearing and childrearing.Citation22 Indonesian women are taught to submit, to be the caregivers and devote their lives to the well-being of their families. Even though more and more Indonesian women are educated or have developed professional careers, marriage and raising a family is still a universal norm. Indonesian women continue to be involved in voluntary community work as an extension of their domestic work. If they find paid work, they will settle for lower wages and other unequal conditions and opportunities.Citation6 In West Java, for example, only a small stipend was provided by BKKBN in 1998 in the amount of Rp. 4000 per month (= US$0.33). Also, gifts such as a tin of biscuits or an umbrella were given annually to every family planning volunteer.

In both rural and urban areas, the educational attainment of women in Indonesia remains lower than that of men. A higher proportion of women than men are non-literate, women are much less likely to be employed full-time and 40% of women aged 15 years and above report housekeeping as their main activity compared to less than 1% for men. Women who work, generally work as unpaid family workers (37%) compared to 9% of men. Decision-making power, policy and programme design and political authority remain a male domain. In the first and second echelons of all government employees and legislative bodies and courts, only about 10% are women.Citation23

A fundamental element of women's empowerment must be participation in decision-making processes, especially decisions concerning their own lives and prioritiesCitation24Citation25Citation26Citation27 and their reproductive health, including timing of pregnancy, birth spacing and childbearing. In Indonesia, a Male Participation Directorate was established in the BKKBN in the year 2000 as well as a Training and Research Centre for Women's Empowerment.Citation28 These policies and programmes were only established when BKKBN was headed by a woman who was also the Minister of Women's Empowerment. However, the philosophical ideas of the domestication of women and the male as the head of the household as well as the family breadwinner still strongly persist in Indonesia and pervade government programmes, including the village family planning volunteers programme. The projects made available to rural women are mostly related to women's traditional roles in the village. The saving and credit schemes and the income-generating groups mostly involve the production of garments, handicrafts, food and beverages. Family welfare and family planning services activities promote family well-being through the maintenance of traditional family roles. Programmes that, in reality, entrench the domestication of women's work are portrayed through special slogans as “increasing women's economic independence”. The burden of caregiver is thus extended beyond the women's own family and children to the community level.Citation29

Discussion

The BKKBN has claimed that among the many laudable features of the Indonesian family planning and family welfare programme has been the level of community participation represented by the volunteers and that the work is empowering for the women.Citation21 However, this work is additional to their own family responsibilities. Does this work empower the women, if they are not being compensated financially? The BKKBN depends heavily on their work and yet, as FolbreCitation30 has argued, caring for others especially children, the elderly and the infirm, work that is heavily loaded towards women, often becomes invisible. Furthermore, Shiffman has recently questioned whether the volunteers' contribution to the Indonesian family planning programme can be seen as genuine community participation because it is a heavily “state-orchestrated initiative” and has “unfolded predominantly according to government plan”.Citation31 We observed this to be the case in this study.

The volunteers were committed to their duties and had little sense that they were being exploited by the BKKBN programme, which appeared to derive from the system of social rewards for good citizenship on which their work was based. Thus, the BKKBN had found creative, successful strategies to promote family planning throughout the nation. However, the burden of work imposed on family planning volunteers and cadres at the village and sub-village levels was quite extraordinary. Without payment and with sometimes little training, these workers carried large, ongoing responsibilities. One small way of rewarding them might be the financial return of the 500–1000 Rp. they have to spend each time they re-supply pills and condoms to eligible couples.Citation32

Based on the study and our own observations, the family planning volunteers and cadres served well in providing family planning information and services, especially to eligible couples and families with children under five, and in delivering a range of other services.

However, the future role of village family planning volunteers in the family planning programme is now in question. After decentralisation of the family planning programme in 2004, many family planning field workers chose to move to other government positions with better status and payment. This has had a strong impact on village family planning volunteers, for whom supervision and training may no longer be available. Thus, whether or not village family planning volunteers remain successful in carrying out their duties depends on the availability of mentoring, supervision and training from other sources.Citation33Citation34Citation35

Acknowledgments

Valuable discussion and comments from Peter McDonald are highly acknowledged. The study was funded by the BKKBN (National Family Planning Coordinating Board), Indonesia.

References

- TH Hull. From family planning to reproductive health care: a brief history. TH Hull. People, Population and Policy in Indonesia. 2005; Equinox Publishing (Asia) and Institute of Southeast Asian Studies: Jakarta, 1–70.

- Indonesian Demographic and Health Survey 1994. Central Bureau of Statistics, State Ministry of Population/National Family Planning Coordinating Board, Ministry of Health, Macro International Inc. Calverton MD, 1995.

- Indonesian Demographic and Health Survey 1996. Central Bureau of Statistics, State Ministry of Population/National Family Planning Coordinating Board, Ministry of Health, Macro International Inc. Calverton MD, 1997.

- Indonesian Demographic and Health Survey 2002-2003. Central Bureau of Statistics, State Ministry of Population/National Family Planning Coordinating Board, Ministry of Health, Macro International Inc. Calverton MD, 2003.

- Hull TH. Caught in transit: questions about the future of Indonesian fertility. Paper presented at Expert Group Meeting on Completing the Fertility Transition. Population Division, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, New York, 11-14 March 2002.

- ID Utomo. Women's lives: fifty years of change and continuity. TH Hull. People, Population and Policy in Indonesia. 2005; Equinox Publishing (Asia) and Institute of Southeast Asian Studies: Jakarta, 71–124.

- Philips JF, Greene WL, Jackson E. Lessons from community-based distribution of family planning in Africa. Policy Research Division Working Paper No.121. New York: Population Council.

- SL Isaacs. Non-physician distribution of contraception in Latin America and the Caribbean. Family Planning Perspectives. 7(4): 1975; 158–164.

- H Suyono, TH Reese. Integrating Village Family Planning and Primary Health Services: The Indonesia Perspective. Technical Report Series No.18. 1978; BKKBN: Jakarta.

- C Lerman, WM John, M Soetedjo. The correlation between family planning program inputs and contraceptive use in Indonesia. Studies in Family Planning. 20(1): 1989; 26–37.

- H Suyono, SH Pandi, IB Astawa. Village Family Planning, the Indonesian Model: Institutionalizing Contraceptive Practice. Technical Report Series, Monograph No.13. 1976; BKKBN: Jakarta.

- J Parson. What makes the Indonesian Family Planning Programme tick. Populi. 11: 1984; 4–19.

- DP Warwick. Bitter Pills: Population Policies and their Implementation in Eight Developing Countries. 1982; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge.

- SM Adioetomo. The construction of a small-family norm in Java. PhD. Canberra: Unpublished dissertation. 1994; Australian National University.

- BKKBN (National Family Planning Coordinating Board). Manual on Contraceptive Service Provision for Village Family Planning Groups (Pedoman Pelayanan Kontrasepsi untuk PPKBD). 1980; BKKBN: Jakarta.

- Hamijoyo SS, Chauls D. Why community participation succeeds in the Indonesian family planning program. Jakarta: BKKBN, (no date).

- BKKBN. Guide on Identification and Cataloguing of Village Family Planning Groups and Acceptor Groups (Petunjuk Inventarisasi PPKBD, sub PPKBD dan Kelompok Peserta KB). 1990; BKKBN: Jakarta.

- BKKBN. Manual on the Development of Village Social Institutions for Family Planning Field Worker Supervisors and Family Planning Fieldworkers (Pedoman Pengembangan Institusi Masyarakat Pedesaan bagi PPLKB, PKB/PLKB). 1995; BKKBN: Jakarta.

- BKKBN. Manual on Rural Community Institution's Roles and Classification (Pedoman Peran dan Klasifikasi Institusi Masyarakat Perdesaan). 1997; BKKBN: Jakarta.

- BKKBN. Development of Rural Community Institution in the National Family Planning Movement (Peningkatan Institusi Masyarakat Dalam Gerakan KB Nasional). 1998; BKKBN: Jakarta.

- BKKBN. Program Profile: the Indonesian National Family Planning and Family Development Movement. 1996; BKKBN: Jakarta.

- Gender Differentiated Impact of Globalization and Macro Economic Changes on Employment in the Rural Sector. 1999; Demographic Institute Faculty of Economics, University of Indonesia: Depok.

- Central Bureau of Statistics. Women and Men in Indonesia 1997. 1998; Statistics Indonesia: Jakarta.

- Asian Development Bank. Gender and Development: Weaving a Balanced Tapestry. Manila: ADB Publication Stock No. 030899. (no date)

- R Dixon-Mueller. Female empowerment and demographic processes: moving beyond Cairo. Contributions to Gender Research. 2001; International Union for the Scientific Study of Population (IUSSP): Paris, 89–122.

- R Dixon-Mueller. Gender inequalities and reproductive health: changing priorities in an era of social transformation and globalisation. Contributions to Gender Research. 2001; IUSSP: Paris, 123–144.

- World Bank. Integrating Gender into the World Bank's Work: A Strategy for Action. 2002; World Bank: Washington DC.

- BKKBN. Minister of Women's Empowerment and Head of BKKBN Decree Number: 060/HK-010/C4/2000 on the Organisation and Work Relation in BKKBN (Keputusan Menteri Negara Pemberdayaan Perempuan dan Kepala Badan Koordinasi Keluarga Berencana Nasional Nomor: 060/HK-010/C4/2000 Tentang Organisasi dan Tata Kerja Badan Koordinasi Keluarga Berencanan Nasional). 2000; BKKBN: Jakarta.

- Parawangsa K. Institutional building: an effort to improve Indonesian women's role and status. Paper presented at Indonesian Update: Gender, Equity and Development in Indonesia's Reform Period. Australian National University, Canberra, 21–22 September 2001.

- N Folbre. The Invisible Heart, Economic and Family Values. 2001; New York Press: New York.

- J Shiffman. The construction of community participation: village family planning groups and the Indonesian state. Social Science and Medicine. 54: 2002; 1199–1214.

- SS Arsyad Rahmadewi. Study on The Development of Village Community Institution Self Reliance in East Java and West Sumatera (Study Pengembangan Kemandirian Institusi Masyarakat Pedesaan di Propinsi Jawa Timur dan Sumatera Barat). Center for Population and Family Planning Studies, BKKBN. 1995

- SS Arsyad. The influence of autonomy of governance on Family Planning Program, 2002. (Pengaruh Otonomi Daerah Terhadap Program KB Nasional). Centre for Research and Development of Family Welfare and Women's Quality Improvement. 2004; BKKBN: Jakarta.

- SS Arsyad. The Study of Family Planning Implementation before the Decentralization Era of Family Planning Program, 2003. (Studi Pelaksanaaan Program Keluarga Berencana Dalam Era Desentralisasi). Centre for Research and Development of Family Welfare and Women's Quality Improvement, BKKBN. 2004; BKKBN: Jakarta.

- SS Arsyad. The Study of Family Planning Implementation during the Decentralization Era of Family Planning Program, 2004. (Studi Pelaksanaaan Program Keluarga Berencana Dalam Era Desentralisasi). 2004; Centre for Research and Development of Family Welfare and Women's Quality Improvement, BKKBN: Jakarta.