Abstract

Without strengthened health systems, significant access to antiretroviral (ARV) therapy in many developing countries is unlikely to be achieved. This paper reflects on systemic challenges to scaling up ARV access in countries with both massive epidemics and weak health systems. It draws on the authors' experience in southern Africa and the World Health Organization's framework on health system performance. Whilst acknowledging the still significant gap in financing, the paper focuses on the challenges of reorienting service delivery towards chronic disease care and the human resource crisis in health systems. Inadequate supply, poor distribution, low remuneration and accelerated migration of skilled health workers are increasingly regarded as key systems constraints to scaling up of HIV treatment. Problems, however, go beyond the issue of numbers to include productivity and cultures of service delivery. As more countries receive funds for antiretroviral access programmes, strong national stewardship of these programmes becomes increasingly necessary. The paper proposes a set of short- and long-term stewardship tasks, which include resisting the verticalisation of HIV treatment, the evaluation of community health workers and their potential role in HIV treatment access, international action on the brain drain, and greater investment in national human resource functions of planning, production, remuneration and management.

Résumé

Seul un renforcement des systèmes de santé permettra à nombre de pays en développement de garantir un large accès à la thérapie antirétrovirale. Cet article réfléchit aux obstacles systémiques contrariant l'accès aux ARV dans des pays où l'épidémie est massive et les systèmes de santé faibles. Il est fondé sur l'expérience des auteurs en Afrique australe et sur le cadre de l'OMS pour l'évaluation de la performance des systèmes de santé. Tout en constatant la persistance des manques financiers, l'article se concentre sur la réorientation des services vers le traitement des maladies chroniques et la crise des ressources humaines dans les systèmes de santé. Des facteurs comme la pénurie de personnel, la distribution inégale, la faible rémunération et la migration accélérée des agents de santé qualifiés sont de plus en plus considérés comme des obstacles systémiques clés à l'élargissement du traitement du VIH. Néanmoins, les problèmes dépassent la question de l'offre pour inclure la productivité et les cultures de la prestation des services. À mesure que davantage de pays reçoivent des fonds pour les programmes d'accès aux antirétroviraux, un fort encadrement national de ces programmes devient de plus en plus nécessaire. L'article propose un ensemble de tâches de supervision à court et long terme, notamment s'opposer à la verticalisation du traitement du VIH, évaluer les agents de santé communautaires et leur rôle potentiel dans l'accès au traitement du VIH, mener une action internationale sur l'exode des cadres et investir davantage dans les fonctions nationales des ressources humaines en matière de planification, production, rémunération et gestion.

Resumen

En muchos países en desarrollo, es improbable que se logre mayor acceso a la terapia antirretroviral (ARV) sin antes fortalecer los sistemas de salud. En este artículo, basado en la experiencia de los autores en África meridional y en el marco de la Organización Mundial de la Salud sobre el desempeño de los sistemas sanitarios, se reflexiona sobre los retos sistémicos relacionados con la ampliación del acceso a los ARV en los países con grandes epidemias y sistemas de salud deficientes. Aunque se reconoce la brecha aún considerable en financiamiento, se destacan los retos en reorientar la prestación de servicios hacia el tratamiento de enfermedades crónicas y la crisis de recursos humanos en los sistemas de salud. El suministro inadecuado, la deficiente distribución, la baja remuneración y la acelerada migración de los trabajadores sanitarios calificados, son considerados cada vez más como limitaciones clave de los sistemas en la ampliación del tratamiento del VIH. Otos problemas son la productividad y las culturas de prestación de servicios. A medida que más países reciben fondos para los programas de acceso a los ARV, también aumenta la necesidad de contar con una sólida administración nacional de esos programas. En este artículo se propone una serie de tareas administrativas de corto y largo plazo: resistencia a la verticalización del tratamiento del VIH, evaluación de los trabajadores de la salud comunitarios y su posible función en ampliar el acceso al tratamiento del VIH, acción internacional respecto al éxodo de profesionales y una mayor inversión en las funciones de planificación, producción, remuneración y administración de los recursos humanos nacionales.

To deny access to life-saving antiretroviral (ARV) therapy, whether on the basis of price or inadequate infrastructure, has become globally untenable. Numerous pilot sites and projects, some internationally celebrated, have demonstrated that it is possible to use ARVs effectively in low-resource settings.Citation1Citation2

As more and more countries receive external resources to embark on HIV treatment programmes, they face a number of questions. Is it possible to make ARVs available to the large numbers of people who need them and what constraints need to be overcome? How will the equity principle be maintained in the inevitably incremental process of scale-up? Is it feasible to manage the investment in ARVs so that they do not divert scarce resources away from other essential activities and instead benefit the health system for delivery of all health programmes?

These questions are not confined to ARV scale-up. A renewed global concern to address the overwhelming disease burdens of the South has repeatedly hit against “the precarious state of health systems in many developing countries”.Citation3 Health systems failures are seen as being at the root of the disappointing outcomes of tuberculosis (TB) control strategies (DOTS),Citation4 Integrated Management of Childhood Illness (IMCI)Citation5 and the integration of reproductive health services.Citation6 Several authorsCitation7Citation8Citation9 have warned of increasing fragmentation and health systems chaos in the wake of the global proliferation of public–private partnerships attempting to tackle HIV in one way or another. The tendency to bypass health systems by creating vertical structures that drain resources from a “crumbling core”Citation10 may address short-term needs but cannot form the basis for universal access. HIV treatment, as with reproductive health services or TB care, and in contrast to polio immunisation or social marketing of bed nets and condoms, cannot be provided in a separate vertical programme without re-creating a whole new parallel health system infrastructure. If ARVs are to reach the huge numbers who need them, and in an organised and regulated manner, the existing health care infrastructure will have to be called upon. The private-for-profit, non-governmental and workplace sectors may have a role to play, but cannot substitute for the core function of the public health sector, both as provider of services and as manager of roll-out.Citation11

This paper reflects on the task of scaling up HIV treatment in the face of generalised HIV epidemics (i.e. massive need) and fragile health systems. It is based on published accounts and the experiences of the authors in the southern African region, a mix of low and middle-income country health systems. Drawing on the World Health Organization (WHO) framework for health systems, the paper begins with a summary of challenges to achieving universal access. It then discusses, in more depth, the need for chronic disease care systems to be integrated into a continuum of HIV care, and the human resource base and cultures of care this presupposes. While in most places universal access will remain a distant goal, almost all health systems have elements of good performance that can form the basis for starting a scale-up process that simultaneously also strengthens the health system itself. Managing these opportunities presents immediate and significant “stewardship” challenges, especially when confronted with the multiplicity of initiatives and sheer pace of the scale-up in many countries. We conclude by summarising what we see as the stewardship tasks, outlined in a matrix of both short- and long-term and micro and macro health systems strengthening tasks.

Overview of health system challenges

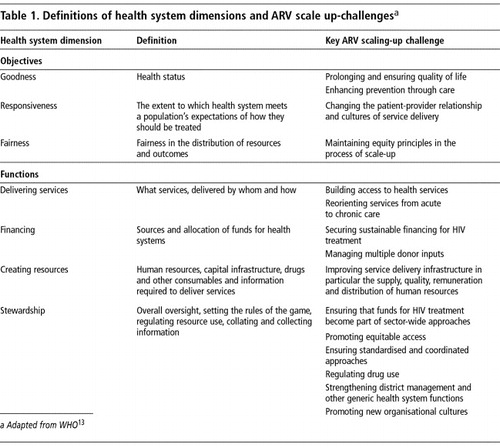

The state of public health systems, particularly in sub-Saharan Africa where ARVs are needed most, is a troubled one. Decades of economic crises, structural adjustments and declining public expenditure have severely undermined the capacity to provide the most basic of health safety nets in many places. Constraints to introducing new health interventions in such environments are numerous and have been comprehensively described by Hanson et al.Citation12 They include demand-side barriers (e.g. affordability, stigma) to accessing services, inadequate service delivery infrastructure, weak drug regulatory and supply systems and the difficulty of managing multiple donor inputs. Table 1 summarises the health system constraints specific to ARV scale-up, in line with the framework proposed by WHO in 2000.Citation13 This framework divides health systems into three objectives (goodness, fairness and responsiveness) and a set of functions (delivering services, creating resources, financing and stewardship) required to achieve these objectives. Although regarded by some as a narrow representation of a health system or of scaling-upCitation12, it does serve as a useful heuristic for considering a classic service delivery intervention such as HIV treatment.

Adequate financing is obviously a key ARV scale-up challenge. Although global funding for HIV/AIDS has increased significantly over the last years, the resources mobilised for treatment still fall far short of need,Citation14 let alone for rebuilding health systems.Citation8 Much of the new funds also bypass and are in danger of overshadowing established national mechanisms for managing external health sector assistance, such as the sector-wide approaches (SWAps).Citation15 However, even if adequate funds were made available through integrated systems, years of under-investment in the resource base of health systems – in particular people and infrastructure – have established difficulties that cannot be reversed in the short term. These macro dimensions of health systems have their counterparts in a set of micro-level service delivery challenges associated with establishing chronic disease care systems. The sections that follow elaborate on these challenges.

Service delivery challenge: antiretroviral therapy as chronic disease care

Antiretroviral therapy, as presently available, is highly effective but complex to manage. It necessitates life-long treatment with at least three antiretroviral drugs (triple therapy or highly active antiretroviral therapy, HAART). Breakthrough drug resistance, followed by rising viral loads and clinical failure is relatively common, even with high levels of adherence.Citation16 This entails ongoing clinical and laboratory monitoring and access to second-line regimens. Side-effects of drugs, especially in the early period of treatment, occur relatively frequently, some of which are sufficiently dangerous to require modifications to treatment. Significant mortality (up to 10%) was found in the early months of treatment in one South African setting.Citation17

Initial experiences in several developing countries have shown that these challenges are not insurmountable.Citation1Citation18 Botswana, a middle-income country of 1.7 million people with a devastating HIV epidemic has instituted a programme of universal access to ARVs. By April 2004, more than 17,000 people had been enrolled onto the programme and adherence rates measured by outcomes such as viral loads were high.Citation19 Médecins sans Frontières (MSF) has comprehensive, district-based HIV/AIDS projects, which include antiretroviral therapy, in 25 countries.Citation20 Many more treatment programmes are being initiated through governments with bilateral and multilateral donor funding.

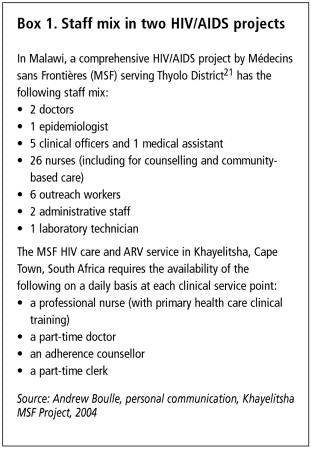

As a rule, these initial pilot projects have set and demonstrated high performance with regards to follow-up, adherence and survival. This performance, however, rests on a significant resource base, involving a relatively complex human resource and systems mix producing a wide range of activities. Treatment programmes include medical staff, mid-level health workers (nurses or clinical assistants), laboratory personnel, lay counsellors, community health workers or treatment supporters and programme managers (seeBox 1). While experience has shown that it is possible to systematise HIV care (including ARVs) into algorithms for application by mid-level workers, especially if combined with strong public health/district support systems,Citation1Citation2 provision still involves mobilising different combinations of skills and at different times. Moreover, it is more doctor-intensive than other primary health care activities such as immunisation and antenatal care.

In these pilot projects, ARVs are also integrated into a wider set of public health, clinical and outreach activities in a “continuum” of care, support and sometimes prevention, which is free at the point of use. Widening HIV testing and enrolling people into follow-up systems of care are central to the success of ARVs. Large-scale, voluntary HIV testing by well individuals, in turn, will only occur if providers are perceived as trustworthy and empathetic. In some programmes, much of the success of ARVs has been attributed to community-based activities involving patient advocacy groups, NGOs or lay counsellors. Such players act as important intermediaries, stimulating demand, reducing social barriers to entry into care and providing social support to people once they are diagnosed and embark on treatment. The precise nature and combination of such social support and the extent to which lay or community-based providers are volunteer or remunerated varies from place to place.

Although treatment for HIV can be managed principally within the primary health care system, doing it effectively is not simple. Ensuring life-long treatment, accessible and well-functioning health facilities, management of referral relationships, partnerships with non-state actors, monitoring and evaluation, and removing the many barriers to entry and remaining in care, all imply a high level of systems and managerial capacity. This makes ARVs more complex than many other health care interventions.

The closest analogy to ARVs in the health system is TB care. HIV care shares many of the well-known features of TB control with the added problem, in common with non-communicable chronic diseases (such as diabetes), of not being curable and requiring treatment over years rather than months. Experiences with TB control, notably the DOTS (“Directly Observed Therapy, Short Course”) Strategy, provide a significant base upon which to draw in programme design and implementation. However, HIV treatment programmes, as described earlier, have departed in important respects from the DOTS approach, specifically in their philosophies of and approaches to partnerships with patients. Strategies have focused on removing utilisation barriers (such as bringing drugs to patients), patient information and provision of social support.Citation1Citation2 In these contexts, adherence is often framed in patient-centred and rights-based discourses around patient empowerment and participation, removal of socio-economic barriers and of agency and dignity. This shift, probably the most complex aspect of replicating successful ARV programmes, implies a new kind of relationship or contract (the negotiated nature of rights, responsibilities and obligations) between providers and patients. This contract is based on very high levels of understanding (“treatment literacy”) on the part of users and the provision of treatment support systems in return for which patients assume new responsibilities – making decisions regarding care, adhering to treatment but also participating in community and prevention activities.

These models of HIV care share more with chronic disease care than TB control. Contemporary approaches to chronic disease care are explicit in highlighting the need for ensuring adequate resources for the technologies of intervention (e.g. protocols and systems) as well as building “informed, motivated and adequately staffed teams”, operating in partnership with “informed and empowered patients”.Citation22 While both are necessary components of a whole, the focus in disease programmes globally has tended to be on technologies rather than on the relationships between people, on the “hardware” rather than “software” of service delivery.Citation23

There are limits to which the complexity of interpersonal and social dimensions of chronic disease care can be minimised by standardised design and protocols. Removing cultural and physical barriers to care and creating organisational cultures in which providers are responsive to patient needs are locally negotiated processes which hinge on a degree of local decision-making and ability to problem-solve. Paradoxically, therefore, building chronic care capacity for HIV/AIDS requires both the dissemination of standardised practices on the one hand, and developing local capacity for decision-making on the other, and about enabling innovation while ensuring conformity to guidelines. It requires the combination of hierarchical, top-down processes with mechanisms to facilitate a fluid and bottom-up process of learning shaped by local actors. Building local capacity in turn requires a renewed focus on the functioning of core health systems structures, namely primary health care and the district health system.

The Médecins sans Frontières project in Malawi providing comprehensive HIV care, described inBox 1, Citation21 invested in strengthening the district hospital by recruiting additional staff externally and by upgrading the local hospital laboratory. Through negotiations, the project introduced a performance-related incentive for all district staff to deal with local tensions around differential salaries between government and NGO staff. The project also recruited national staff from outside the district and made sure that all health care staff had access to ARVs. Drug supplies were procured and distributed largely through existing mechanisms. Local initiatives such as this provide important examples on strengthening health systems through HIV/AIDS, especially if supported by national processes which encourage sharing of lessons and which direct new resources to replicate such experiences elsewhere. However, they speak little to achieving these effects on a system-wide national level. The project employed 41 Malawi nationals, a situation which would not be feasible in every district without some concerted national action to increase the supply of human resources. In this country, recruitment by non-governmental HIV/AIDS projects appears to be a major reason for loss of staff from public sector institutions.

The challenge of creating resources

Although most health systems contain successful examples of service delivery for TB, chronic diseases and in recent times ARVs, expanding access beyond these islands of success faces significant obstacles. The inadequate supply (and in fact a growing crisis in the supply) of skilled and motivated health care workers is now regarded as the key systems constraint to scaling up of HIV treatment.Citation24Citation25Citation26Citation27

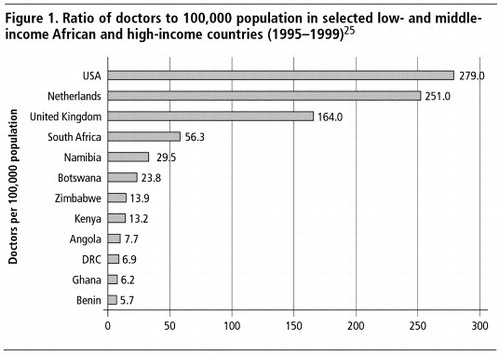

The problem of human resource development is multi-faceted – it includes supply, migration, distribution, skills mix, remuneration and productivity dimensions.Citation28 Despite the conventional view of African public health sectors as bloated,Citation29 the health worker-to-population ratios of developing country health systems remain vastly inferior to those of industrialised nations ().

Ratio of doctors to 100,000 population in selected low- and middle-income African and high-income countries (1995–1999)Citation25

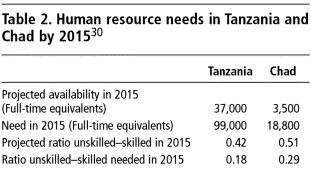

When measured against need, the shortfalls in developing countries are considerable. Kurowski et alCitation30 estimated the human resource requirements necessary to meet essential health care needs, including HIV treatment, in Tanzania and Chad. Their case studies indicated a 2.7 and 5.4-fold gap, respectively, in the necessary size of the health sector workforce (Table 2). There was also an imbalance between unskilled and skilled staff.

The South African government calculated that 13,805 new health professionals (doctors, nurses, pharmacists, dieticians and counsellors) would be needed by 2008 to meet the targets of the Operational Plan for Comprehensive HIV and AIDS Care, Management and Treatment.Citation31 Yet in 2003, there were 52,574 unfilled professional posts in the South African public health sector, representing a 31.1% vacancy rate.Citation32

Seen over time, the supply of health professionals in most African countries has not always been as limited as it is now. After an initial period of growth in supply, most countries have experienced a consistent decline in the availability of human resources. The current situation is the product of multiple pressures over several decades – reduced social sector expenditure, dramatic and sometimes overnight drops in real incomes of health professionals, a consequent decline in their “social value” and status,Citation33 less investment in training and production of new cadres, a failure to retain those that are trained, and HIV infection.

While the African continent has for decades experienced a brain drain of skilled human resources, the evidence points to a greatly accelerated recent process of international migration, generated by a human resource crisis (albeit relative) in the health systems of the industrialised North.Citation33 Despite the paucity of data and lack of standardised measures documenting migration trends, indications are of a staggering flow of health personnel out of developing countries. For example, nearly 500 doctors and more than 1,000 nurses from South Africa register annually with the United Kingdom General Medical Council.Citation34 Kenya has lost 4,000 nurses to the UK and US; in Zimbabwe, only 360 of 1,200 doctors trained during the 1990s were still practising in their country in 2000,Citation25 and so on. While the traditional flow out of countries has been of doctors, the recruitment of nurses has now overtaken that of doctors.Citation34 Vacancy rates in some countries, despite inadequate staff establishments, are extremely high, of the order of 30–40% of public sector posts for professional staff.Citation25Citation29 Even Botswana, a middle-income country able to attract professionals from other countries, is only able to fill 78% of doctor posts and 81% of nursing posts.Citation3

Aggregate ratios of health personnel at national level hide large disparities within countries; the brain drain is as much an internal problem as an international one. The liberalisation of the private for-profit sector in many countries and the proliferation of non-governmental organisations have made possible a flight out of the public sector and rural areas within countries.Citation35 The consequences of such flows are not only shortages but also a high turnover of staff and loss of institutional memory.

Initiatives over time to protect the human resource base of health systems are poorly documented – there is very little literature to be found on now several decades of experience with mid-level cadres (e.g. auxiliaries and assistants) in many countries.Citation36 HIV/AIDS responses have themselves given rise to a large infrastructure of community and home-based carers, often based in non-governmental organisations. Relying mostly on a volunteer or semi-remunerated base, this constitutes a significant de facto workforce presence in the health sector. For example, there were an estimated 30,000 community-based carers in South Africa in 2002 which government plans to formalise into an infrastructure of community health workers who are managed by NGOs but supported and regulated by the state.Citation37 The extent to which the existing and emerging skills base of health systems can be mobilised for HIV care is inadequately understood.

High levels of HIV infection amongst health personnel may be one contributor to attrition of personnel in some countries.Citation38 By the late 1990s, deaths constituted more than 40% of all nurses lost to the public sector in Malawi and Zambia,Citation29 while in South Africa in 2002, 16.3% of health workers were infected with HIV.Citation39

Health workers in many countries, particularly lower level cadres, are paid salaries well below subsistence levels. Non-payment of salaries is not uncommon.Citation40 Moreover, with currency devaluations and salary freezes imposed through structural adjustment programmes, many health workers have experienced dramatic reversals in their incomes over time.Citation25 A poorly remunerated workforce is unlikely to be a productive one. McPake et alCitation40 observed in Uganda that “utilisation levels are less than expected… and the workload is managed by a handful of the expected staff complement who are available for a fraction of the working week”. Following an assessment of the availability and time use of staff in their two country case studies, Kurowski et alCitation30 concluded that major gains in human resource supply could be made by focusing in the first instance on improving the productivity of staff. They estimated that improved productivity would increase the supply of personnel by 26% in Tanzania and 35% in Chad.

Cultures of service delivery

A less tangible but no less significant dimension of the human resource crisis is the demoralisation and demotivation of those remaining within the system.Citation28 Demotivated health workers are less inclined to orient their actions towards the achievement of organisational goals and may be less willing to balance self-interested behaviour with altruism and solidarity towards users of services.Citation41 In many health systems, underpaid health workers have increasingly looked to health systems as a means to ensure their own survival rather than as an avenue for expression of professional and societal norms of caring and altruism.Citation40Citation42Citation43

Mackintosh and Tibandebage describe how in one hospital they investigated in Tanzania: “nurses were caught between many of the worst pressures on the system: low and declining wages, poor chances of advancement, poor and often dangerous working conditions, and an experience of abandonment by the doctors formally responsible for patient care. This sense of being abused has in the worst cases turned full circle into a culture of abuse of patients” (p.8).Citation42 Predatory behaviour towards the state/public health system on the one hand and towards patients on the other hand is sufficiently rampant as to constitute a set of norms or values that powerfully shape the everyday practice of health care providers in many health systems.Citation43 The manifestations include the near universal practice of informal, illegal fees in poor countries, use of public facilities for private gain, absenteeism, re-selling of state-provided drugs and denying emergency care unless payments are made.

While improvements in the supply and remuneration of health care workers is a necessary precondition for the reversal of these norms, they will not be sufficient on their own: “The problems of demoralization and negative attitudes are more complex than money and call for a multi-dimensional rehabilitation program involving measures of both the carrot and stick.”Citation44 Abuse of patients should thus not be seen purely as a phenomenon of rent-seeking in the face of poverty. Such behaviours are well-described in health systems where health workers earn living wages. In South Africa, for example, public sector health workers are frequently described as harsh, unsympathetic and readily breaching patient confidentiality.Citation45 In the context of HIV treatment, these entrenched norms of service delivery limit the ability to create individualised, patient-centred therapeutic partnerships premised on rights and equality between providers and patients. In addition, poorly planned and overly hasty introduction of new drugs into such environments may promote perverse incentives and informal economies of drug use that undermine access and accelerate the development of drug resistance.

The challenge of stewardship

In the face of overwhelming difficulty, conventional portrayals of public services in developing countries, by both policymakers and the public, are typically negative and often expressed in fatalistic terms. However, Mackintosh and Tibandebage caution against an excessively pessimistic view of health systems and suggest that organisational cultures are, in reality, highly variable and open to influence. Thus, in the same Tanzanian context described above: “a number of facilities, seemingly against the odds, were providing accessible care in decent conditions, stretching resources effectively for the benefit of users, treating patients with respect” (p.10).Citation42 Summary statements on the problems confronting health systems fail to acknowledge what may be important elements of resilience and functionality within systems. These provide clues as to the possibilities for building on existing strengths. Factors such as the quality of facility and district leadership may be key to such variation and are deserving of further attention. Fairness in allocation of career and training opportunities, for example, are often powerful signals of local management cultures and significantly influence motivation.Citation24 Through their discourse and practice, leaders and managers set the frames for what is acceptable and unacceptable in health system practice. Leadership that recognises, champions and rewards facilities, districts or health system foci that express appropriate norms and values may form the starting point for influencing norms and values more generally.Citation42

Shaping values forms an essential part of the oversight of health systems referred to by WHO as “stewardship”, the process of setting the rules of the game, determining not only the content of health policy but also the mechanisms by which policy is implemented.Citation46 Although a national function, effective stewardship is as much a global concern insofar as international responses to the health crisis in sub-Saharan Africa have often served to fragment, rather than strengthen, the sovereign capacity of country health systems.Citation9Citation10

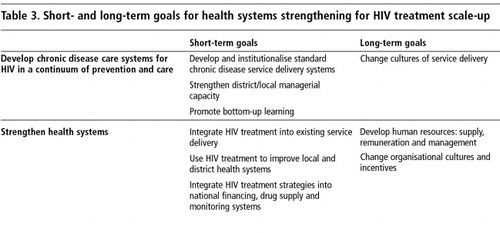

In a context of multiple pressures – international and national expectations, proliferation of donor assistance, the danger of drug resistance and need for capacity development and innovation at all levels of the health system – appropriate national stewardship of HIV treatment programmes is not only an essential but also a highly strategic task. It involves a willingness to view the resources mobilised for HIV as an opportunity to re-build national health systems, whilst simultaneously creating the capacity to respond to the immediate need for access to treatment. The challenge can be summarised as a set of short-term and long-term goals focused on the development of systems (embodied in the notion of chronic disease care) for HIV treatment specifically and health systems more generically (Table 3).

Systems for chronic disease care would include setting national standards (e.g. on drug regimens), enabling sharing of local experiences and lessons learned, opening up debates on the patient–provider relationship, and as the scale-up process proceeds, monitoring equity of access. Effective stewardship also requires resisting the tendency towards verticalisation (often in order to meet targets) of programme initiatives and ensuring that treatment access occurs as much as possible in an integrated fashion through the existing public health system. This requires identifying opportunities for building on existing strengths (such as sector-wide approaches) and finding ways to draw in the multiplicity of actors on the margins of the formal health system. Integration can be viewed at a number of levels: at the point of service delivery, in the management of programmes at district or local level, and in the financing, procurement of resources and monitoring of programmes at national level.

There is growing consensus that a long-term perspective on ARV scale-up has to address the critical shortage of human resources.Citation28 This would include at a minimum:

| • | promoting international action on the brain drain; | ||||

| • | at country level (re)investment in traditional human resource functions such as planning, production, remuneration and management of health care providers; | ||||

| • | addressing macro-economic constraints on employment and remuneration of health care providers; | ||||

| • | evaluation of the performance of existing nationally developed cadres such as mid-level and community health workers and their potential role in HIV treatment scale-up. | ||||

Conclusions

Without strengthened or even transformed national health systems it is hard to see how access to ARVs can be sustainably achieved in countries with weak health systems. To be effective, ARVs also require integration into a continuum of HIV care, best modelled on understandings developed in the field of chronic disease care. The scale of this challenge in countries with generalised HIV epidemics cannot be under-estimated. However, insofar as the ARV scale-up process cannot avoid drawing attention to health system weaknesses, it provides an opportunity, firstly, to reassert a coherent approach to national health systems and secondly, to ensure that funds mobilised for treatment access are oriented towards long-term goals, rather than just short-term access targets.

Acknowledgements

This paper has its origins in a longer monograph prepared for the Global Health Policy Research Network (PRN), funded by the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation and housed in the Center for Global Development, Washington, DC. The monograph is available at <http://www.wits.ac.za/chp>.

References

- P Farmer, F Leandre, J Mukherjee. Community-based treatment of advanced HIV disease: introducing DOT–HAART (directly observed therapy with highly active antiretroviral therapy). Bulletin of World Health Organization. 79(12): 2001; 1145–1151.

- T Kasper, D Coetzee, F Louis. Demystifying antiretroviral therapy in resource-poor settings. Essential Drugs Monitor. 32: 2003; 20–21.

- Joint Learning Initiative. Human Resources for Health and Development: A Joint Learning Initiative. 2003; Rockefeller Foundation: New York.

- P Nunn, A Harries, P Godfrey-Fausset. The research agenda for improving health policy, systems performance and service delivery for tuberculosis control: a WHO perspective. Bulletin of World Health Organization. 80: 2002; 471–476.

- J Bryce, S el Arifeen, G Pariyo. Multi-country evaluation of IMCI Study Group. Reducing child mortality: can public health deliver?. Lancet. 362: 2003; 159–164.

- L Lush, J Cleland, G Walt. Integrating reproductive health: myth and ideology. Bulletin of World Health Organization. 77: 1999; 771–777.

- Wemos Foundation. Good intentions with side-effects: Information on Global Public-Private Initiatives in Health. 2004; Wemos Foundation: Amsterdam.

- D McCoy, M Chopra, R Loewenson. Expanding access to antiretroviral therapy in sub-Saharan Africa: avoiding the pitfalls and dangers; capitalizing on opportunities. American Journal of Public Health. 95(1): 2005; 18–22.

- DM Saunders, M Chopra. Confronting Africa's health crisis: more of the same will not be enough [Education and Debate]. BMJ. 331: 2005; 755–758.

- R Loewenson, D McCoy. Access to antiretroviral treatment in Africa [Editorial]. BMJ. 328: 2004; 241–242.

- World Health Organization. Health and the Millennium Development Goals. 2005; WHO: Geneva.

- K Hanson, KM Ranson, V Oliveira-Cruz. Expanding access to priority health interventions: a framework for understanding constraints to scaling up. Journal of International Development. 15: 2003; 1–14.

- World Health Organization. The World Health Report 2000. Health Systems: Improving Performance. 2000; WHO: Geneva.

- S Rosen, I Sanne, A Collier. Rationing antiretroviral therapy for HIV/AIDS in Africa: choices and consequences (Policy Forum). Public Library of Science Medicine. 2(11): 2005; e303. At: <http://medicine.plosjournals.org. >.

- A Cassels. A Guide to Sector-Wide Approaches for Health Development: Concepts, Issues and Working Arrangements. 1997; World Health Organization: Geneva.

- N Singh, SM Berman, S Swindells. Adherence of human immunodeficiency virus-infected patients to antiretroviral therapy. Clinical Infectious Diseases. 29(4): 1999; 824–830.

- D Coetzee, K Hildebrand, A Boulle. Outcomes after two years of providing antiretroviral treatment in Khayelitsha, South Africa. AIDS. 18: 2004; 887–895.

- D Coetzee, A Boulle, K Hildebrand. Promoting adherence to antiretroviral therapy: the experience from a primary care setting in Khayelitsha, South Africa. AIDS. 18(Suppl.3): 2004; S27–S31.

- MASA Antiretroviral Therapy. Access for All: The Masa Programme – providing all Batswana with access to care and treatment. Vol.9, June/July 2004.

- Médecins sans Frontières. Antiretroviral Therapy in Primary Health Care: Experience of the Chiradzulu Programme in Malawi Case Study. Briefing Document. 2004; MSF: Malawi.

- J Kemp, JM Aitken, S Le Grand. Equity in health sector responses to HIV/AIDS in Malawi. Discussion Paper 5. 2003; Equinet: Harare.

- T Bodenheimer, EH Wagner, K Grumbach. Improving primary care for patients with chronic illness: the chronic care model, part 2. Journal of the American Medical Association. 288: 2002; 1909–1914.

- D Blaauw, L Gilson, L Penn-Kekana. Organisational relationships and the “software” of health sector reform. Background paper. Disease Control Priorities Project. 2003. At: <www.fic.nih.gov/dcpp/. >.

- C Hongoro, B McPake. Human resources in health: putting the right agenda back to front [Editorial]. Tropical Medicine and International Health. 8: 2003; 965–966.

- B Liese, N Blanchet, G Dussault. The Human Resource Crisis in Health Services in Sub-Saharan Africa. Background paper. 2003; World Bank: Washington DC.

- K Kober, W van Damme. Scaling up access to antiretroviral treatment in southern Africa: who will do the job?. Lancet. 364(9428): 2004; 103–107.

- L Chen. Hanvoravongchai. HIV/AIDS and human resources [Editorial]. Bulletin of World Health Organization. 83(4): 2005; 243–244.

- L Chen, T Evans, S Anand. Human resources for health: overcoming the crisis. Lancet. 364: 2004; 1984–1990.

- USAID. The Health Sector Human Resource Crisis in Africa: An Issues Paper. 2003; USAID, AED, SARA: Washington DC.

- C Kurowski, K Wyss, S Abdulla. Human resources for health: requirements and availability in the context of scaling-up priority interventions in low-income countries. Case studies from Tanzania and Chad. Report to the Department for International Development. 2004; LSHTM, IDRC, STI: London.

- South African Department of Health. Operational Plan for Comprehensive HIV and AIDS Care, Management and Treatment for South Africa. November. 2003; Department of Health: Pretoria.

- A Padarath, A Ntuli, L Burthiaume. Human resources. PI Ijumab, C Day, A Ntuli. South African Health Review 2003-04. 2004; Health Systems Trust: Durban.

- B Marchal, G Kegels. Health workforce imbalance in terms of globalization: brain drain or professional mobility. International Journal of Health Planning and Management. 18(Suppl.1): 2003; S89–S101.

- B Stilwell, K Diallo, P Zurn. Developing evidence-based ethical policies on the migration of health workers: conceptual and practical challenges. Human Resources for Health. 1(1): 2003; 8. At: <http://www.human-resources-health.com/. >.

- Padarath A, Chamberlain C, McCoy D, et al. Health personnel in southern Africa: confronting maldistribution and brain drain. Equinet Discussion Paper No.3. Zimbabwe: Equinet, Health Systems Trust, MEDACT, (undated).

- D Dovlo. Using mid-level cadres as substitutes for internationally mobile health professionals in Africa. A desk review. Human Resources for Health. 2: 2004; 7. At: <http://www.human-resources-health.com/. >.

- I Friedman. CHWs and Community Care-givers: Towards a Unified Model of Practice. P Ijumba, P Barron. South African Health Review 2005. 2005; Health Systems Trust: Durban.

- L Tawfik, S Kinoti. The Impact of HIV/AIDS on the Health Sector in Sub-Saharan Africa: the Issue of Human Resources. 2002; SARA, AED, USAID: Washington DC.

- O Shisana, E Hall, KR Maluleke. The Impact of HIV/AIDS on the Health Sector: National Survey of Health Personnel, Ambulatory and Hospitalised Patients and Health Facilities, 2002. 2002; Human Sciences Research Council, Medical University of South Africa, Medical Research Council: Pretoria.

- B McPake, D Asiimwe, F Mwesigye. Informal economic activities of public health workers in Uganda: implications for quality and accessibility. Social Science and Medicine. 49: 1999; 849–865.

- LM Franco, S Bennett, R Kanfer. Health sector reform and public sector health worker motivation: a conceptual framework. Social Science and Medicine. 54: 2002; 1255–1266.

- M Mackintosh, P Tibandebage. Sustainable redistribution with health care markets? Rethinking regulatory intervention in the Tanzanian context. Discussion Papers in Economics No.23. 2000; Open University: Milton Keynes.

- W Van Lerberghe, C Conceiçao, W Van Damme, P Ferrinho. When staff is underpaid: dealing with the individual coping strategies of health personnel. Bulletin of World Health Organization. 80(7): 2002; 581–584.

- M Segall. District health systems in a neoliberal world: a review of five key policy areas. International Journal of Health Planning and Management. 18(Suppl.1): 2003; S5–S26.

- L Gilson, N Palmer, H Schneider. Trust and health worker performance: exploring a conceptual framework using South African evidence. Social Science and Medicine. 61: 2005; 1418–1429.

- P Travis, D Egger, P Davies. Towards Better Stewardship: Concepts and Critical Issues. CJL Murray, DB Evans. Health Systems Performance Assessment Debates, Methods and Empiricism. 2003; WHO: Geneva.