Abstract

In sub-Saharan Africa, health systems are fragile and staffing is grossly inadequate to meet rising health needs. Despite growing international attention, donors have been reluctant to undertake the significant investments required to address the human resources problem comprehensively, given social and political sensitivities, and concerns regarding sustainability of interventions and risks of rising donor dependency. In Malawi, one of the poorest nations in Africa, declining human resource levels have fuelled an accelerating collapse of public health services since the late 1990s. In an effort to improve health outcomes, in 2004 the government launched a new health initiative to deliver an Essential Health Package, including a major scale-up of HIV and AIDS related services. Improving staffing levels is the single biggest challenge to implementing this approach. Donors agreed to help the government develop an Emergency Human Resources Programme with five main facets: improving incentives for recruitment and retention of staff through salary top-ups, expanding domestic training capacity, using international volunteer doctors and nurse tutors as a stop-gap measure, providing international technical assistance to bolster planning and management capacity and skills, and establishing more robust monitoring and evaluation capacity. Industrial relations were a prominent consideration in determining the shape of the Programme. The combination of short- and long-term measures appears to be helpful in maintaining commitment to the programme.

Résumé

En Afrique subsaharienne, les systèmes de santé sont fragiles et les effectifs très insuffisants pour répondre aux besoins grandissants. Malgré une attention internationale croissante, les donateurs n'ont guère investi pour traiter globalement le problème des ressources humaines, en raison des sensibilités sociales et politiques, et des préoccupations concernant la viabilité des interventions et les risques d'augmenter la dépendance à l'égard des donateurs. Au Malawi, l'un des pays les plus pauvres d'Afrique, le déclin des niveaux des ressources humaines a accéléré l'effondrement des services de santé publique depuis la fin des années 90. En 2004, le Gouvernement a lancé une nouvelle initiative destinée à assurer un ensemble essentiel de santé, qui comprend un élargissement majeur des services liés au VIH/SIDA. La principale difficulté d'application de cette approche est l'amélioration des niveaux des effectifs. Les donateurs ont accepté d'aider le Gouvernement à préparer un programme d'urgence pour les ressources humaines avec cinq volets principaux : relever les incitations au recrutement et à la rétention du personnel par des primes salariales, renforcer la capacité nationale de formation, faire appel à des médecins et des tuteurs infirmiers bénévoles internationaux comme mesure temporaire, fournir une assistance technique internationale pour soutenir la capacité et les compétences en planification et gestion, et consolider la capacité de suivi et d'évaluation. Les relations professionnelles ont joué un rôle majeur dans la préparation du programme. La combinaison de mesures à court et long terme semble aider à maintenir l'engagement en faveur du programme.

Resumen

En África subsahariana, los sistemas de salud son frágiles y el número de empleados es muy inadecuado para cubrir las necesidades de salud. Pese a la creciente atención internacional, los donantes se han mostrado renuentes a emprender las considerables inversiones necesarias para tratar el problema de recursos humanos de manera integral, en vista de las sensibilidades sociales y políticas, y las inquietudes respecto a la sostenibilidad de las intervenciones y los riesgos de la creciente dependencia en los donantes. En Malaui, una de las naciones más pobres de África, la baja en recursos humanos ha exacerbado el acelerado fracaso de los servicios de salud pública desde finales de los 1990. En un esfuerzo por mejorar la salud, en 2004 el gobierno lanzó una nueva iniciativa en salud para hacer disponible un Paquete Esencial de Salud, que incluye la gran ampliación de los servicios relacionados con el VIH/SIDA. Para ejecutar esta estrategia, el mayor reto resulta incrementar el número de empleados. Los donantes acordaron ayudar al gobierno a crear un Programa de Recursos Humanos de Urgencia con cinco facetas principales: mejorar los incentivos para contratar y retener al personal mediante salarios adicionales, ampliar la capacidad de capacitación nacional, emplear médicos voluntarios y enfermeras tutoras internacionales como una medida provisional, brindar asistencia técnica internacional para reforzar la capacidad y las habilidades de planificación y administración, y mejorar la capacidad de monitoreo y evaluación. Las relaciones industriales fueron un factor prominente en determinar cómo anda el programa. La combinación de medidas de corto y largo plazo parece ser de utilidad para conservar la dedicación al programa.

Following work by the Commission for Macroeconomics and Health on the importance of improved health for economic growth and human development, international attention has focused on providing more equitable, cost-effective funding mechanisms to make health services available to poor people, as well as strengthening national health systems to deliver them.Citation1 Frequently described as the glue that holds together health systems, links between human resources and health outcomes have in turn been spotlighted. For example, the results of research commissioned by the Joint Learning Initiative on Human Resources “strongly confirm the importance of human resources for health in affecting health outcomes”.Citation2 At a practical level, the 2003 WHO Report on Global Tuberculosis (TB) Control cites lack of human resources as the main reason why reaching its global targets was put back from 2000 to 2005.Citation3Citation4

Evidence from Malawi, one of the poorest countries in southern Africa, where health indicators have historically been poor, suggests that declining human resource levels have fuelled an accelerating collapse of public health services since the mid-1990s. As a result, the health sector has struggled to keep pace with demand for services, particularly given population growth and high levels of HIV and AIDS. An April 2004 report from the Ministry of Health stated that the human resources situation in the health sector has been described as “critical, dangerously close to collapse, collapsed, meltdown” and that the health sector is “facing a major, persistent and deepening crisis with respect to human resources”.Citation5

During a joint visit to Malawi in 2004, Peter Piot, Head of UNAIDS, and Suma Chakrabarti, Permanent Secretary of the UK Department for International Development (DFID), instructed their agencies to support development of a Malawian-led initiative to address the human resources crisis. Their concern was that without a substantial increase in health workers, it would not be possible to roll out antiretroviral treatment without further undermining the already weak health system. The result was a shift from piecemeal donor support for a number of uncoordinated initiatives to a more comprehensive approach, through an “Emergency Human Resources Programme” which is now being implemented.

Demographic and economic background

With an estimated GDP per head of US$149 in 2003, Malawi's population ranks among the poorest in Africa.Citation6Citation7 Dependent on rain-fed smallholder agriculture, over half of the 12 million population is food insecureCitation8 and 65.3% are unable to meet their daily consumption needs.Citation9 In addition to high levels of overall poverty, distribution of income and consumption is also highly unequal.Citation10

International aid contributes approximately US$45.4 per capita to Malawi and represented 31.2% of Gross National Income in 2003, a much higher proportion than that of other countries in sub-Saharan Africa.Citation6Citation11 Within the health sector, donor contributions provide approximately US$4 of the total health expenditure of US$12.4 per person. Government spending accounts for approximately US$3 per person and the rest is provided by private sources, which among the poor come mostly from out-of-pocket expenditure.Citation12

Health infrastructure in Malawi is reasonably well-developed, comprising four central (tertiary) hospitals, two psychiatric hospitals, 22 district hospitals, 23 mission hospitals (managed on a private, not-for-profit basis) and 397 health centres, plus smaller health posts and dispensaries. However, it is in overwhelmingly poor condition: among health centres a 2003 survey found 243 to have no operational water source, 204 with no operational electricity and 244 without an operational communications system (radio or telephone).Citation13 Government housing for health workers serving in many rural areas is similarly dilapidated and lacks basic services.

Malawi's health indicators reflect the depth and severity of its poverty. Life expectancy at birth has dropped from 46 years in 1996 to 37.5 years in 2003, mainly as a result of HIV and AIDS: infection rates are high, estimated at 14.2% among 15–49 year olds.Citation10 Almost half of children under the age of five are chronically under-nourished and despite improvements in infant and child mortality rates in the past five years, nearly one in seven children still dies before their fifth birthday.Citation14 Maternal mortality doubled in the 1990s from 620/100,000 live births to 1,120/100,000 live births in 2000, amongst the highest levels in the world.Footnote*

Despite poor health indicators overall, Malawi has seen some important successes in recent years. Neonatal tetanus and polio have been eliminated through immunisation programmes, coverage of insecticide treated bed nets to tackle malaria has rapidly increased to 42% of all households, and TB cure rates of over 70% have been maintained despite the high mortality rate fuelled by AIDS.Citation14Citation15 However, these gains have mainly been achieved through targeted, donor-funded, vertical interventions. Meanwhile the overall capacity of the public health system has steadily declined as the government strives to provide universal health care free of charge to a population growing at a rate of 23% every ten years.Citation16 This diminishing capacity in the health sector reflects a parallel decline in the effectiveness and efficiency of Malawi's public services overall.Citation17 Broadening and sustaining improvements in Malawi's health indicators to achieve the Millennium Development Goals is unlikely without substantial systems strengthening. Key to this will be addressing the critical shortages of human resources.

Human resources in Malawi's health sector

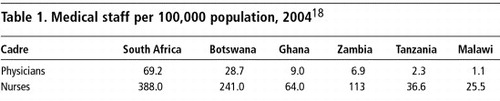

Current staffing in Malawi is the lowest in the region, as shown in Table 1, and is inadequate to maintain a minimum level of health care.

There are shortages across all professional cadres. Malawi has one doctor per 62,000 population and vacancies among obstetrician–gynaecologists, paediatricians, surgeons and other medical specialists range between 71–100%. There are only three fully qualified pharmacists in the public sector. Vacancies among nurses stand at 65%. Uneven distribution of staff is also a major challenge. Half of Malawi's doctors work at one of four central hospitals, while 16 districts have no Ministry of Health doctor and until recently four districts had no doctor at all (Personal communication, Ministry of Health official, February 2006). A 2003 survey found that 15 of Malawi's 26 districts had on average less than 1.5 nurses per facility, and five districts had less than one.Citation5Citation19

The imperative to increase staffing

The government launched a new health initiative in 2004 designed to deliver an Essential Health Package, a prioritised set of cost-effective interventions to address the 11 major causes of illness and mortality.Citation20Footnote* Provided free-of-charge to all Malawians, this package represents an explicit form of rationing, identifying certain services as high priority, but in turn recognising that “if services are to be provided for all, then not all services can be provided”.Citation21 It contrasts with previous disease-specific, vertical approaches in its focus on district level services, integrating primary care with effective referral. Among other goals, it aims to deliver reproductive health services, including improved access to and referrals between basic and comprehensive emergency obstetric care, which is essential to reduce Malawi's high level of maternal mortality.

Improving staffing levels is the single biggest challenge to full implementation of the new approach. An independent review of a recent donor-funded safe motherhood project, which “quickly halved the proportion of deaths among hospital deliveries” concluded that “despite extensive staff training and support, the severe staff shortages arising from problems with retention and continued attrition in numbers of midwives, is proving to be an important obstacle to increasing coverage of births by skilled attendants and puts at risk the gains in quality of care”.Citation22 At 57%, the proportion of recent births assisted by a doctor or nurse at delivery has been virtually unchanged since 1992.Citation14 The recent publication of the Road Map for Accelerating the Reduction of Maternal and Neonatal Mortality and Morbidity in Malawi underscores staff shortages and weak human resource management as the first of multiple factors affecting levels of skilled attendance.Citation23 Only 13% of health facilities have 24-hour coverage by midwives.Citation13

As part of the Essential Health Package, Malawi's government has developed ambitious plans for prevention and treatment of sexually transmitted infections, HIV/AIDS and related complications, including antiretrovirals (ARV) and voluntary counselling and testing (VCT).Citation20 Nearly one million 15-49 year olds are infected with HIV and an estimated 170,000 people are currently in need of ARV therapy.Citation24 Since mid-2004, despite severe constraints, Malawi's government has demonstrated success in mounting a successful treatment programme using a simple but effective approach through the public health system. In mid-2003 ARV provision was limited to four sites, benefiting less than 1% of those in need.Citation25 By December 2005, following major investment by the Global Fund for AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria and other donors, nearly 38,000 patients had started treatment, free of charge, at 60 public health facilities, and 23 private facilities had started treating almost 1,000 more.Citation26 The rate at which medical staff can be sourced and trained is the major constraint on the pace of scaling up HIV and AIDS related services.Citation5 Over 1,100 public sector clinicians and nurses as well as approximately 230 private sector staff have received specialist training to deliver ARV and VCT services, working on a rotational basis. In addition, staff are required for complementary activities, including treatment of opportunistic infections and prevention of mother-to-child-transmission (PMTCT), which are also expanding.Citation26Citation27Footnote*

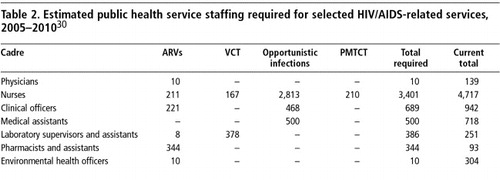

As provision of these services began in 2004, the government's specific aim was to achieve 35,000–45,000 patients receiving ARVs by July 2005, but an “aspirational goal” was also set to scale up ARV provision to 80,000 patients by late 2005, in line with the WHO 3x5 Initiative.Citation8Citation28 Given the major staffing implications, a rapid estimation of projected requirements was carried out (Table 2). The projection starkly highlighted the scale of the challenge of ensuring sufficient staff to support these activities without compromising other essential services, including complementary sexual and reproductive health services, which are critical for addressing HIV over the longer term. Work was also initiated to consider more innovative approaches to staffing, such as using lower and non-clinical cadres for patient follow-up and monitoring, and training nurses to distribute drugs directly to patients to alleviate demand for pharmacy services. (Personal communication, Ministry of Health HIV and AIDS Unit official).Citation29

Causes of the human resources crisis

There are three main reasons for Malawi's chronic shortage of medical personnel. The root cause is poverty. Malawi has historically been unable to sustain the costs of training and employing enough health sector staff to meet basic health care needs. It has for decades relied upon expatriate doctors, and even following the establishment of its medical school in 1991 produced only 20 doctors per year until 2005, of whom over half have gone into research, teaching, further training or private practice in Malawi or overseas. Malawi has produced 40–60 registered nurses annually in recent years, alongside approximately 300–350 enrolled nurses.Citation31 This compares to an establishment for public sector nurses (including mission hospitals) of 8,963, of which an estimated 4,934 posts are vacant.Citation5 Even assuming that all nurses trained were joining the public sector, with increasing outflows of staff, the rate of training has not kept pace with need.

In the last ten years, HIV/AIDS-related attrition among health sector staff has compounded the shortages.Citation32 Malawi's Five Year Human Resources Development Plan 1999–2004 assumed total annual losses of 2.8% based on personnel data.Citation33 This is widely considered to underestimate true outflows from the sector. For example, a 2002 study of rural and semi-urban areas in Malawi showed that among hospital health care workers annual death rates alone were at 2%.Citation34 The impact of HIV and AIDS on staffing is much broader than attrition. There are reports of nurses leaving their profession due to fear of exposure to HIV, particularly as shortages of gloves and other supplies hamper adherence to universal precautions.Citation25Footnote* Staff time is lost through funeral attendance, and staff may be absent for prolonged periods due to illness. There is no policy, nor sufficient spare capacity for replacing staff who are chronically sick. While workloads have increased, reflecting population growth and rising morbidity associated with AIDS, there are fewer staff to share the burden. In addition, nurses in particular are often called to act as primary carers for sick members of their family or community.Citation35

Thirdly, much of the investment made in training health personnel is being lost as increasing numbers of professional and technical staff choose to move out of the public sector. Whereas 20 years ago, health worker salaries in many African countries were considered attractive, real wages for civil servants in Malawi and elsewhere have failed to keep pace with rising consumer prices in recent years.Citation36 Large numbers of staff have moved into Malawi's small but expanding private health sector where wages are typically three or four-fold those of government, including a rapidly growing number of NGOs and research initiatives, mostly associated with the HIV and AIDS pandemic.Citation5Citation37

Low pay is only part of the reason why staff leave the public service. Difficult working conditions with infrequent supervision and support, lack of essential drugs, supplies and equipment, limited career opportunities caused in part by rigid professional barriers, high and uneven workloads, lack of a clear deployment policy, inequitable access to training and inadequate housing all contribute to low morale and frustration. Malawi's Nurses and Midwives Council estimates that up to 1,200 qualified nurses living in Malawi have chosen to stop working in the health sector altogether, switching to better-paid or less stressful vocations.Citation5

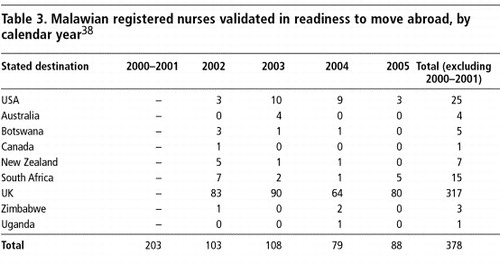

International migration of Malawi's nursing staff has increased considerably in recent years. Since 2000, approximately 80–100 nurses each year have sought validation of their certificates in order to work abroad (Table 3), primarily in the UK.Citation38 In an era of globalisation, medical professionals with internationally recognised qualifications have become “tradable commodities”, moving with relative ease across borders. Malawi's nurses, while desperately needed at home, are no exception.

In contrast, although insufficient numbers of doctors are produced, Malawi has a reasonable record of retaining those who enter government service (Personal communication, Principal, Malawi College of Medicine). Since 1988 doctors and dentists have been permitted to practice privately in addition to their public service obligations. This has worked well in terms of retention, although weak regulatory capacity in Malawi raises questions about the balance of hours spent on public sector work vs. private practice.

Malawi has adjusted training structures repeatedly since the late 1990s in response to growing staff shortages. For example, training of medical assistants (a Malawi-specific, male-dominated cadre, which shares common skills with nurses and primarily serves in rural postings) was re-introduced in 2001, following a hiatus of five years. Without an internationally recognised qualification, almost no medical assistants have migrated out of Malawi, in sharp contrast to their nurse colleagues.

Examining the evidence

Faced with a worsening human resources situation and committed to launching the Essential Health Package, including an ambitious range of HIV/AIDS-related services, in early 2004 the Ministry of Health declared a human resources crisis in the health sector.Citation5 Donors responded, providing technical expertise to assist the Ministry in quantifying staffing targets and calculating the financial implications of implementing a six-year Emergency Human Resources Programme. Its design was based on research, policy reports and data available on establishments and vacancy rates.

While there were no international models of similarly large-scale, comprehensive programmes on human resources for health, programme design drew upon lessons from initiatives tried elsewhere in the region.Citation39 Government also built on a number of existing, separate initiatives in Malawi, including a 1999 Human Resources Development Plan, a 2001 Emergency Training Programme, long-standing use of expatriate doctors for key posts, and previous, more piecemeal measures to improve remunerative incentives, including a targeted incentive package for nurse tutors.Citation40Citation41Citation42

Given the paucity of detailed data on staffing levels and factors affecting retention and motivation, programme design drew heavily upon formal and informal consultations to tap the knowledge and experience of stakeholders across government, non-governmental service providers, training schools, regulatory agencies, professional associations and donors. Those consulted unanimously agreed on the immediate need to tackle pay issues, but underscored the equal importance of tackling longer-term, more complex issues including, inter alia, human resources management capacity, career structures, staff deployment and working conditions. This consultation process highlighted the need to strengthen the new Health Services Commission (established in 2002) and ensure better coordination between this body and the Ministry of Health. The process also reinvigorated Malawi's Human Resources Advisory Committee (for health) formed in 2000 to bring together all key players in this area, but which had fallen dormant. This group has since guided and overseen programme implementation.

Industrial relations were a prominent consideration in the decision-making on the shape of the programme. For example, it was agreed that there were limited possibilities for using volunteer expatriates to fill gaps in the nursing cadres, even though this was seen as the single most significant constraint on health service provision. While recruitment of nurse tutors from overseas was deemed acceptable, as they were specialists in very limited supply in Malawi, the option of recruiting expatriate nurses was rejected because of the perceived high risk (based on past experience) of industrial action by Malawian nurses. On the other hand, while nurses were recognised as the cadre most in need of additional incentives, raising remuneration for nurses without doing the same for other professional and technical cadres would have led to problems within the health workforce.

Developing a strategy for action

Costed at US$272 million, the resulting six-year Emergency Human Resources Programme commenced in earnest in April 2005. With major funding from the Government of Malawi, DFID and the Global Fund for AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria, it aims to raise Malawi's staffing to Tanzanian levels which, while still far short of WHO-recommended minimums, represent an ambitious, but attainable goal. The programme is based upon a detailed, costed model, linking progressive staffing targets across 11 professional and technical cadres with recruitment and training requirements.Footnote*

The programme takes a five-pronged approach, aiming to achieve short-term improvements while pursuing longer-term goals. Focal areas include:

| • | improving incentives for recruitment and retention of Malawian staff in government and mission hospitals through a 52% taxed salary top-up for 11 professional and technical cadres, coupled with a major initiative for recruitment and re-engagement of qualified Malawian staff; | ||||

| • | expanding domestic training capacity by over 50% overall, including doubling the number of nurses and tripling the number of doctors in training; | ||||

| • | using international volunteer doctors and nurse tutors as a stop-gap measure to fill critical posts while more Malawians are being trained; | ||||

| • | providing international technical assistance to bolster capacity and build skills within the Ministry of Health's human resources planning, management and development functions; and | ||||

| • | establishing more robust monitoring and evaluation capacity for human resources in the health sector, nested within existing health management information systems, which are being strengthened to support implementation of the Essential Health Package.Citation43 | ||||

In addition to immediate implementation of these activities, the programme explicitly recognises the importance of longer-term work on a range of additional factors affecting retention, including policies on postings and promotions, training, skills upgrading and career development opportunities. Work on developing a policy and incentives for deploying staff to underserved areas was initiated to improve the distribution of staffing across the country. This includes a major effort to improve staff housing and draws on experience from elsewhere in the region in piloting a package of location-specific incentives.

The programme was framed to complement implementation of the Essential Health Package, which will impact on workplace satisfaction. These include better maintenance and upgrading of facilities and equipment, and adequate and timely provision of essential drugs and medical supplies: ensuring that health workers have the tools they need to do their jobs. Supervisory and support structures are also being strengthened through the establishment of four zonal support offices.

An important challenge was ensuring that the programme – and particularly proposals for salary top-ups – was sensitive to the country's tight macro-economic situation. It was therefore devised to be fully funded by donors, except that government would contribute some of the resources gained by taxing donor-funded top-ups. Six salary top-up scenarios were initially presented and discussed in great detail over a period of months. Over twelve further permutations were also considered. Increasing staff compensation had implications for the Government's pension fund and agreements with the International Monetary Fund (IMF), with whom a special agreement was reached.

The decision to finance salary top-ups in the health sector reflected an explicit decision by donors “to consider measures that might otherwise be dismissed as unsustainable” because of the scale of the crisis and its implications.Citation44 The major funders took the view that Malawi was likely to receive high levels of aid for the foreseeable future. In addition, the form of aid was also changing in the sector, away from projects to budget support. The relevant questions in terms of financing were both what would happen to the top-ups at the end of the programme, and more importantly, whether the volume of expenditure for health (to support an expanded health workforce) represented an affordable proportion of Government's budget beyond the current six-year time frame.

DFID concluded that taking account of Government of Malawi resources and assuming continued aid flows, there were likely to be sufficient resources to finance the higher levels of health staff aimed at by the programme. In addition, donors reached an explicit agreement with the government that the proportion of the national budget spent on health would be maintained or increased over the course of the six years (Personal communication, Head of DFID-Malawi). The main risk was that aid flows might be disrupted for other reasons, for example, a breach of an IMF programme or human rights problems that might cause donors to reduce aid flows through government. In order to persuade the government to undertake the risk of higher levels of expenditure supported by aid, DFID committed to give two financial years' notice of the withdrawal of the salary component of its aid.Citation43 In addition, the top-ups were deliberately framed within the government's pay policy. Over time, they will be dwarfed by wider pay rises, given Malawi's high inflation, unless a subsequent decision is taken to increase them.

Progress to date

Implementation of the programme started in earnest in April 2005 with the start of salary top-ups. By that time international volunteer organisations, including the UK's VSO and United Nations Volunteers, had made good progress on recruitment of stop-gap international support with 19 expatriates already in Malawi. By April 2006, 51 expatriate doctors and 15 nurse tutors are scheduled to be in post.Citation45 Three human resources experts were in post by August 2005, to bolster Ministry of Health capacity and support implementation of the programme. By January 2006, the first phase of construction began, in line with prioritised and costed infrastructure development plans to expand training capacity.

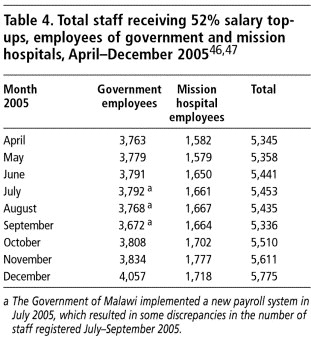

Results so far indicate that salary top-ups are having a positive impact on staffing levels, as shown in Table 4. Total numbers of employees receiving top-ups increased by 430 after nine months, compared with a programme target of 700 in the first year. Informal interviews with hospital managers across the country indicate that top-ups have significantly stemmed the flow of staff, particularly nurses, out of the public sector. Detailed data on outflows are still being collected.

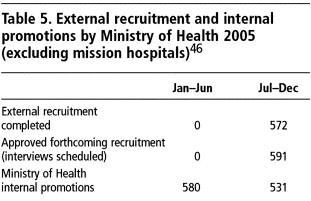

Implementation of the planned recruitment and re-engagement drive was slow to start while Ministry of Health sought permission from other parts of government to engage new staff and negotiated improved arrangements for re-contracting those who have already reached the compulsory retirement age of 55 years (or 20 years of service). However, by the last quarter of 2005, good progress had been made with 591 staff recruited externally (Table 5). Some of those recruited have yet to take up their posts and hence are not yet reflected in the payroll figures in Table 4. In addition, over 1,100 have been promoted internally. Many of these were nurses whose promotions were blocked by civil service rules following a previous change in the nursing curriculum. This had been a source of frustration for the nursing profession, affecting retention.

In addition, a survey of qualified Malawian health professionals who had retired or resigned from Government was recently completed. Of over 1,000 respondents, nearly 700 indicated their willingness to return to government employment given the offer of salary top-ups and more flexibility over deployment decisions, coupled with opportunities for further training (Personal communication, Chair, Health Services Commission, Malawi).

In sum, the top-ups appear to be effective in attracting and improving retention of staff in the sector, particularly middle- and lower-ranking cadres. The one exception is international nurse migration, which did not appear to slow down in 2005 (see Table 3). It is likely that these nurses began preparations to migrate prior to the start of the programme, so it is too early to tell whether the programme (coupled with new measures by the UK Department of Health) has reduced migration (Personal communication, Director, Nurses and Midwives Council, Malawi). Furthermore, Ministry of Health data, while questionable, suggest that the number of Registered Nurses resigning or absconding in 2005 fell dramatically from previous years, so those nurses going overseas may already have retired or been working in the private sector. Regardless of where they came from, though, these most senior and experienced nurses are lost to Malawi at least temporarily, and from the pool of those who might be re-engaged under the programme.

Government has introduced a period of compulsory public health service for enrolled nurses trained at public expense. International experience suggests that such bonding is ineffective in tackling international migration, but this initiative is targeted at those leaving the public service shortly after qualification for better paid jobs within Malawi. The impact will not be visible until these nurses qualify.

Finally, progress to establish robust monitoring and evaluation capacity has been slow. There has been little regular data collection on human resources in recent years and improving the timeliness and quality of reporting requires stronger management capacity, which is still being built. Data analysis and evaluation capacity also need strengthening. Programme monitoring has so far focused on operational issues, using a variety of sources. Measures to strengthen the capacity of health management information systems are linked with implementation of the Essential Health Package, and are moving forward.

Lessons learned and future issues

Why has this approach been possible in Malawi? In the past, donors were reluctant to contribute to incentives packages or salaries given concerns about donor dependency and the sustainability of their interventions.Citation48 However, it became apparent through donor evaluation that the lack of human resources was a binding constraint on the success of donor-funded projects, particularly those focused on sexual and reproductive health and safe motherhood. Project-related donor support for human resources was piecemeal; the scale and type of donor support was simply not commensurate with the scale of the problem.

What has changed is that some donors and Government are now driven by an outcome-based approach. This is linked to a shift away from projects, in favour of programme-based aid instruments, including budget support. In this case, both donors and the Malawi government were committed to scaling up provision of antiretroviral drugs, while also progressing towards other health targets, most importantly that of maternal mortality. Their analysis showed that the binding constraint was staffing. Even so, it took the intervention of the heads of two international agencies more comfortable with taking risks – UNAIDS and DFID – to authorise their local offices to back the initiative. Other more risk-averse agencies, such as the Global Fund, followed their example. It was only when, in Malawi, one donor publicly signalled that it was prepared to consider “exceptional measures that might otherwise be deemed unsustainable” that Ministry of Health clearly articulated a full set of proposals.

This is a key lesson for other countries. In Malawi, a donor lead was necessary because donors have for so long signalled that they could not help to address pay. Many other countries in Africa would probably benefit from similarly wide-ranging support. The top management of some donor agencies are encouraging a comprehensive response.

Secondly, major investment in human resources in Malawi only makes sense within the context of a broader programme addressing health service provision. Working conditions and management practices are as important an incentive as pay; providing drugs, gloves, equipment, decent infrastructure and adequate supervision are central to improving morale and retention.

Thirdly, while it is too early to judge whether these measures will impact on health outcomes in Malawi, the combination of short- and long-term measures appears to be helpful in maintaining commitment to the programme, by giving an impression of change in the short term. For example, salary top-ups had immediate impact and will gradually help ease workloads. The appearance of expatriate support in districts previously without doctors is another visible sign of change. The programme is explicitly buying time until the impact of longer-term measures, such as expanding training capacity, improving career structures and changing management practices can be felt.

Fourth, weak institutional capacity is at the heart of Malawi's human resources situation. Vacancy levels are high across the civil service, particularly amongst middle management, and the capacity and discipline of the civil service has declined markedly since the early 1990s.Citation17 A chronic lack of capacity in the Ministry of Health's human resources function, and the fragmentation of human resources responsibilities within the Ministry and across government, affected Malawi's ability to recognise and respond to the growing difficulties until long after they reached crisis proportions. Because the Ministry entrusted programme design and early implementation to a small core of competent and dedicated staff, answering directly to senior officials, speedy progress was made. But this also led to patchy ownership of the initiative within the Ministry, which has hampered integration of human resources interventions into broader government planning processes and monitoring. Donors exacerbate these problems to the extent that they apply particular conditions to their aid. This can be avoided where donors pool their funding.

Weak capacity is evident in the difficulties of establishing programme monitoring and evaluation capacity to demonstrate progress in terms of outputs and outcomes. Strong pressure exists to “projectise” monitoring and evaluation by creating a more effective parallel system, but this would forego the opportunity to strengthen systems more broadly. The best approach is not yet clear.

Fifth, Malawi's experience highlights how important and time-consuming the management of industrial relations is, both within the health sector and in relation to other sectors. Having a good map of sensitivities, which are country-specific, proved crucial to successful implementation at the start of the programme. Surprisingly, the only group that reacted to the implementation of top-ups were some of the beneficiaries: nurses at one of the Central Hospitals staged a one-day strike on the first day they received their increased pay packets. Disgruntled at the decision to tax the top-ups, these nurses cried foul, suspecting that government was holding back donor funds that were rightfully theirs. The issue was resolved within a matter of hours, but highlighted the importance of government communications with staff. Speculative announcements by members of the Government prior to agreement on the scale of the top-ups, coupled with insufficient subsequent communication, allowed staff expectations to rise unrealistically in the months prior to implementation. Malawi would have benefited from more professional input here. While pay negotiations are not an appropriate area for direct donor involvement, it would be possible to provide government with expert advice.

Contrary to expectations, other public servants did not protest at the improved pay for health workers. The Government presented the case for higher pay for health workers as a reward for their longer training and higher professional skills. This built upon a precedent set by previous special remunerative allowances for health workers (although the Ministry of Finance was taking steps to end such allowances across Government as part of efforts to rationalise the payroll). Footnote*

Sixth, it is too early to tell whether the Emergency Human Resources Programme will help reduce nurse migration. Even when measures are taken to put a stop to active recruitment (as has occurred with the tightening of the UK Department of Health's Code of Practice for the international recruitment of health care professionals), the momentum of passive migration, once established, appears harder to stem.Citation49 Ongoing international migration of Malawi's nurses is a cause for concern. It attracts the most senior and experienced staff, most of whom have already served ten years or more in country. Bonding would be inappropriate after that length of service, and is not known to have halted international migration elsewhere. The demand for skilled health workers in rich countries will continue to rise. It is therefore likely that African countries, including Malawi, will continue to lose some of their most skilled workers. Thus, Malawi will need to produce staff over and above those required domestically. It will need to track migration trends, as well as leakage of nurses from the public sector to other jobs within Malawi, which the programme does seem to be reducing.

Finally, the imperative of responding to HIV and AIDS presents an ongoing human resources challenge in Malawi. Impressive early achievements spurred government in late 2005 to map out an ambitious expansion plan for HIV and AIDS-related services, including delivery of ARV therapy to 245,000 people by 2010.Citation24 This acceleration has obvious implications for human resources, and risks depleting staff from provision of other essential services, including sexual and reproductive services, which are central to longer-term management of HIV.Citation50 A full workload analysis for HIV and AIDS services is planned and careful consideration of the staffing balance across services will be necessary.

Acknowledgements

Grateful thanks to Dr Mike O'Carroll, Dr Julia Kemp and in particular Roger Wilson for their comments on an earlier draft of this article. I am also indebted to many officials in the Ministry of Health, Health Services Commission, Nurses and Midwives Council, Malawi Medical Council, Christian Health Association of Malawi and Malawi's health training institutions for their insights and generosity in sharing data.

Notes

* Preliminary indications from Malawi’s 2004 Demographic and Health Survey suggest maternal mortality has declined slightly since 2000.

* The Essential Health Package covers vaccine-preventable diseases, malaria, reproductive health, tuberculosis, schistosomiasis, acute respiratory infections, acute diarrhoeal diseases, sexually transmitted infections, HIV/AIDS, malnutrition and nutritional deficiencies, eye, ear and skin infections, and common injuries.

* The numbers of women receiving PMTCT are presently low. In 2004, out of 540,000 deliveries only 7.9% women were tested for HIV. A meagre 2.7% of pregnant women in need of ARV prophylaxis received the intervention. Malawi aims to increase the number of women tested from 100,000 in 2006 to 400,000 by 2010 and provide ARV prophylaxis to 65,000 women/child pairs by 2010. Demand for VCT is also rising: in 2004, nearly 285,000 persons were tested for HIV in 146 public sector sites, up from 150,000 in 2002. Ministry of Health data also indicate a rising incidence of tuberculosis, Karposi’s sarcoma, cryptococcal meningitis and oesophageal candidiasis.

* A 2003 survey revealed that 49% of health care workers giving vaccinations and 57% of those giving curative injections reported a needle-stick injury in the previous 12 months. While health workers have access to antiretroviral treatment, and post-exposure prophylaxis also recently became available, informal reports suggest some hesitate to come forward for testing due to stigma and fear that patients will refuse care from them.

* The eleven cadres are doctors, nurses, clinical officers, medical assistants, pharmacists, laboratory technicians, radiographers, physiotherapists, dentists, environmental health officers and medical engineers.

* The configuration of trade unions in Malawi also helped avert tension. While midwives, nurses and doctors have their own professional associations, other professional health workers do not, and instead rely on Malawi’s Civil Service Union for representation. With members who would benefit from top-ups, as well as members who would not, the Civil Service Union took no action to oppose implementation of the remunerative increases.

References

- WHO Commission on Macroeconomics and Health. Macroeconomics and Health: Investing in Health for Economic Development. 2001; WHO: Geneva.

- S Anand, T Baernighausen. Human Resources and Health Outcomes. Joint Learning Initiative - Human Resources for Health and Development. Working Paper 7/2, 2003. At: <http://www.globalhealthtrust.org/Publication.htm. >.

- AD Harries, R Zachariah, K Bergstrom. Human Resources for Control of Tuberculosis and HIV-Associated Tuberculosis. International Journal of Tuberculosis and Lung Disease. 9(2): 2005; 128–137.

- World Health Organization. Global Tuberculosis Control: Surveillance, Planning, Financing. 2003; WHO: Geneva.

- Ministry of Health, Malawi. Human Resources in the Health Sector: Towards a Solution. 2004; Government of Malawi: Lilongwe.

- Malawi Country Data Profile. World Bank Group. At: <http://devdata.worldbank.org/external/CPProfile.asp?CCODE=MWI&PTYPE=CP. >.

- Economist Intelligence Unit. Malawi Country Background. At: <http://www.viewswire.com. >. Accessed 7 February 2006.

- Malawi Global Fund Coordinating Committee. An Integrated Response to HIV/AIDS and Malaria: Application to the Global Fund. National AIDS Commission. 2002; Government of Malawi: Lilongwe.

- National Statistics Office, Malawi. 1998 Integrated Household Survey: Summary Report. 2000; National Statistics Office: Zomba.

- United Nations Development Programme. Human Development Report 2005. 2005; UNDP: New York.

- Data from Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development. At: <http://www.oecd.org/dataoecd/23/20/1882063.gif>.

- Ministry of Health and Population. Malawi National Health Accounts: a broader perspective of the Malawian Health Sector. 2001; Ministry of Health: Lilongwe.

- Ministry of Health and Population. Malawi Health Facility Survey. 2003; Government of Malawi: Lilongwe.

- National Statistics Office. Malawi Demographic and Health Survey. Preliminary Report. 2004; National Statistics Office: Zomba.

- Ministry of Health. National Tuberculosis Programme Annual Report 2004. 2004; Government of Malawi: Lilongwe.

- UNFPA. State of the World's Population 2005. 2005; UNFPA: New York.

- D Durevall. Reform of the Malawian public sector: incentives, governance and accountability. S Kayizzi-Mugerwa. Reforming Africa's Institutions: Ownership, Incentives, and Capabilities. 2003; UNU Press: Tokyo.

- WHO. Global Health Atlas – An Interactive World Map. http://atlas.globalhealth.org/

- Planning Department, Ministry of Health. Annual Report of the Work of the Malawi Health Sector for the Year July 2004–June 2005. 2005; Government of Malawi: Lilongwe.

- Planning Department, Ministry of Health. Joint Programme of Work for a Health Sector Wide Approach (SWAp) 2004–2010. Annex 6. 2004; Government of Malawi: Lilongwe.

- Essential Health Package Working Group, Ministry of Health and Population/UNICEF. Malawi Essential Health Package, Revised Content and Costings. Lilongwe: Government of Malawi, December 2001/ May 2002. p.6.

- C Lenton, S Gibson, G Maclean. 2003 Output to Purpose Review of the Safe Motherhood Project Malawi. London. 2003; UK Department for International Development.

- Ministry of Health. Road Map for Accelerating the Reduction of Maternal and Neonatal Mortality and Morbidity in Malawi. 2005; Lilongwe: Ministry of Health.

- Ministry of Health. Treatment of AIDS: Five-Year Plan for the Provision of Antiretroviral Therapy and Good Management of HIV-Related Diseases to HIV-Infected Patients in Malawi 2006–2010. December. 2005; Government of Malawi: Lilongwe.

- J Kemp, J-M Aitken, S LeGrand. Equity in Health Sector Responses to HIV/AIDS in Malawi. Equinet Discussion Paper No.5. August. 2003; EQUINET/ Oxfam GB: Lilongwe.

- HIV and AIDS Unit, Ministry of Health. 12-Monthly Report from the Clinical HIV Unit, MOH: January–December 2005. 2005; Ministry of Health: Lilongwe.

- Ministry of Health. Prevention of Mother to Child Transmission of HIV: A Five Year Plan for the Provision of PMTCT Services in Malawi 2006 – 2010, Draft (V2). 2005; Government of Malawi: Lilongwe.

- J-W Lee. Global health improvement and WHO: shaping the future. Lancet. 362: 2003; 2083–2088.

- Malawi Global Fund Coordinating Committee. Health Systems Strengthening and Orphan Care and Support: Application to the Global Fund Fifth Call for Proposals. 2005; National AIDS Commission, Government of Malawi: Lilongwe.

- AL Martin-Staple. Proposed 6-Year Human Resource Relief Programme for the Malawi Health Sector. June. 2004; Department For International Development: London.

- University of Malawi College of Medicine, University of Malawi Kamuzu College of Nursing and Malawi College of Health Sciences. Unpublished data on student enrolments.

- United Nations Development Programme. The Impact of HIV/AIDS on Human Resources in the Malawi Public Sector. 2002; UNDP: Lilongwe.

- Ministry of Health and Population. Five-Year Human Resources Development Plan 1999–2004. Vol. III, 1998; Lilongwe: Government of Malawi.

- AD Harries, NJ Hargreaves, JH Kwanjana. High death rates in health care workers and teachers in Malawi. Transactions of Royal Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene. 96: 2002; 34–37.

- J-M Aitken, J Kemp. HIV/AIDS, Equity and Health Sector Personnel in Southern Africa. Equinet Discussion Paper No.12. EQUINET/Oxfam, September 2003. At: <http://www.equinetafrica.org. >.

- TR Valentine. Towards a Medium Term Pay Policy for the Malawi Civil Service: Final Report. Presented to Department of Human Resource Management and Development and Ministry of Finance and Economic Planning, Malawi. 2003; Government of Malawi: Lilongwe.

- EN Banda, G Walt. The private health sector in Malawi: opening Pandora's Box. Journal of International Development. 7(3): 1995; 403–421.

- Nurses and Midwives Council of Malawi. Data, 19 January 2006.

- Joint Learning Initiative. Human Resources for Health: Overcoming the Crisis. 2004; President and Fellows of Harvard College: Cambridge MA.

- Public Sector Change Management Agency, Government of Malawi. Ministry of Health and Population Unit Review: Implementation Report and Action Plan. 1998; Government of Malawi: Lilongwe.

- Ministry of Health and Population. Government of Malawi Project Financing Proposal for Human Resources Development in the Health Sector. 2000; Government of Malawi: Lilongwe.

- Planning Department, Ministry of Health and Population. A 6-Year Emergency Pre-Service Training Plan. November. 2001/ July 2002Government of Malawi: Lilongwe.

- Department For International Development. Improving Health in Malawi: £100 million UK Aid (2005/6– 2010/11). A Sector Wide Approach including Essential Health Package and Emergency Human Resources Programme. Programme Memorandum, November 2004. 2004; DFID: London.

- P Piot, S Chakrabarti. Malawi Visit by the Director of UNAIDS and the Permanent Secretary of DFID 8 –11 February 2004. Joint Report. February. 2004; UNAIDS and London: Department For International Development: Geneva.

- Ministry of Health Human Resources Management and Development Section, Data, 2006.

- Ministry of Health. Human Resources Management and Development Section, Data, February 2006.

- Christian Health Association of Malawi Secretariat. Data, February 2006.

- T Martineau, J Martinez. Human Resources in the Health Sector: an International Perspective. 2002; DFID Health Systems Resource Centre: London, 8.

- Department of Health, UK. Code of Practice for the International Recruitment of Healthcare Professionals. 2004; Department of Health: London.

- AD Harries, D Nyangulu, N Hargreaves. Preventing antiretroviral anarchy in sub-Saharan Africa. Lancet. 358(9279): 2002; 410–414.