Abstract

Around the world, midwives are increasingly being called upon to provide skilled care for pregnant women and newborns. In Morocco, there is a persistent lack of professional recognition of midwifery, which is consistent with widespread gender inequality and women's low status. Midwifery training in Morocco has evolved since the 1960s into a three-year undergraduate programme. Despite this, there is currently a shortfall of midwives to attend the large number of births in Morocco. Midwives have only partially replaced traditional birth attendants, especially in rural areas. Maternal mortality remains high. However, several recent government policies reflect increased attention to women's needs, e.g. since February 2006, midwives may be eligible for reimbursement should a medical doctor be unavailable. Since 1990, the Moroccan Midwives Association has been actively encouraging midwifery curriculum review, improvements in training and the professional status of midwifery. Partnerships with international midwifery associations have revealed challenges encountered elsewhere and helped us to establish specific strategies for promoting the professional recognition, autonomy and visibility of midwifery in Morocco. In a cultural context such as Morocco's, a disciplinary link between midwives and the medical community seems crucial. However, only with recognition of midwives as competent, skilled and valued partners can midwifery practice in Morocco progressively evolve into women-centred maternity care.

Résumé

De par le monde, les sages-femmes sont de plus en plus souvent appelées à dispenser des soins qualifiés aux femmes enceintes et aux nouveau-nés. Au Maroc, la profession souffre d'un manque persistant de reconnaissance professionnelle, qui coïncide avec une inégalité sexuelle très répandue et un statut féminin médiocre. Depuis les années 60, la formation des sages-femmes est devenue un programme universitaire de trois ans. Pourtant, le Maroc connaît une pénurie de sages-femmes pour assister les nombreux accouchements. Les sages-femmes n'ont que partiellement remplacé les accoucheuses traditionnelles, particulièrement dans les régions rurales. La mortalité maternelle demeure élevée. Néanmoins, plusieurs politiques gouvernementales récentes montrent une attention accrue aux besoins des femmes. Ainsi, depuis février 2006, les honoraires des sages-femmes peuvent être remboursés en cas d'indisponibilité du médecin. Depuis 1990, l'Association marocaine des sages-femmes encourage la révision du programme d'études des sages-femmes, et demande des améliorations de leur formation et de leur statut professionnel. Les partenariats avec les associations internationales de sages-femmes ont permis à l'Association de connaître les obstacles rencontrés ailleurs et l'ont aidée à définir des stratégies spécifiques pour promouvoir la reconnaissance professionnelle, l'autonomie et la visibilité des sages-femmes au Maroc. Dans le contexte culturel du pays, un lien disciplinaire entre les sages-femmes et la communauté médicale semble essentiel. Néanmoins, seule une reconnaissance des sages-femmes comme partenaires compétentes, qualifiées et utiles permettra à la profession d'évoluer progressivement vers des soins obstétricaux centrés sur la femme.

Resumen

A nivel mundial, cada vez más se solicita a las obstetrices que proporcionen atención competente a las mujeres embarazadas y los recién nacidos. En Marruecos, existe una persistente falta de reconocimiento profesional de la obstetricia (partería), lo cual concuerda con la amplia desigualdad de género y el bajo estatus de las mujeres. La formación en obstetricia ha evolucionado desde la década de los 1960 hacia un programa de pre-grado de tres años. Pese a ello, actualmente existe una escasez de obstetrices para atender al gran número de partos en Marruecos. Éstas han sido sustituidas parcialmente por parteras tradicionales, especialmente en las zonas rurales. La tasa de mortalidad materna continúa elevada. No obstante, recientes políticas gubernamentales reflejan mayor atención a las necesidades de las mujeres: p. ej., desde febrero de 2006, las obstetrices tienen derecho a solicitar un reembolso si un médico no está disponible. Desde 1990, la Asociación de Obstetrices de Marruecos ha fomentado una revisión del currículo de obstetricia, mejorías en la capacitación y la validez profesional de la obstetricia. Las alianzas con asociaciones internacionales de obstetricia han demostrado los retos encontrados en otros lugares y nos han ayudado a establecer estrategias específicas para promover el reconocimiento profesional, la autonomía y la visibilidad de la obstetricia en Marruecos. En un contexto cultural como éste, parece fundamental establecer un vínculo disciplinario entre las obstetrices y la comunidad médica. Sin embargo, sólo al reconocerse la competencia, las habilidades y el valor de las obstetrices podrá evolucionar la práctica de obstetricia progresivamente hacia una atención a la maternidad centrada en las mujeres.

Midwives are increasingly being called upon to meet the growing demand for care of mothers and newborns in birthing homes, maternity hospitals and land-locked rural centres in Morocco. Despite the urgent need for holistic woman-centred care, midwifery practice remains greatly influenced by a medical emphasis on the conditions associated with pregnancy and birth. There is also a persistent lack of recognition of midwifery as a professional and autonomous practice in Morocco. This is consistent with an inherent system of widespread gender inequality maintaining a large majority of women in a low status.Citation1Citation2Citation3 Hence, the services provided by midwives remain largely invisible, as do the needs of the women they are trained to attend.

Despite an acute lack of scientific evidence and systematically documented information regarding the practice of midwifery in Morocco, a discussion of midwifery practice in Morocco is timely. Recent statistics on births and maternal mortality, as well as changes in the regulations governing midwifery practice, are among the reasons why. This article describes the evolution of midwifery education and the practice of midwifery in Morocco since the mid-20th century, from the time the UN Convention on Maternity Protection was revised.Citation4 The history of midwifery practice in Morocco is illustrated from research reports, where available, as well as statistical data from the Moroccan Ministry of Health, the United Nations and the World Health Organization.

Midwifery training in Morocco: a complex pathway

Midwifery as it is practised in present-day Morocco is the outcome of a complex history of varied forms of educational training. Before 1950, obstetric care was provided only by untrained traditional birth attendants (kablas) at women's homes in rural and semi-urban regions. Today, kablas, with limited official midwifery training, continue to offer assistance at delivery and post-natal care mostly in remote areas. They are acknowledged and respected by rural communities for their maturity and their role as confidantes. While the very nature of their care – centred on women and provided by women – offers opportunities for rural women's reproductive empowerment, it also inadvertently reinforces prevailing gender constructs in Moroccan society.

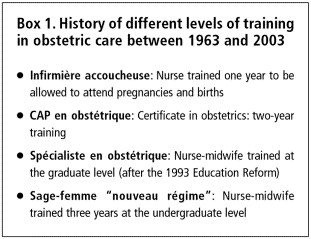

As early as the 1950s and until the 1960s, official programmes for women interested in attending births, known as moualidates, were designed (Box 1). Initially, a two-year programme was initiated in Rabat, the capital city under the French Protectorate.Citation5 Although only a primary school certificate was required to be eligible for this training, a limited number of women were trained, because it was socially unacceptable in those days for women to move to Rabat to study. In 1960, in order for moualidates to be able to attend births and provide perinatal care, a one-year course leading to a Professional Aptitude Certificate following the moualidate training was required. This was extended to two years in 1970.Citation5 It was expected that the women who gained this Certificate would work mostly in the rural areas, though untrained kablas continued to provide such care there as well.

In the meantime, in the 1950s, monitoring pregnancy and delivering babies in urban health institutions became one of the responsibilities of other female health workers, ranging from auxiliaries to nurses, but always acting under medical authority.Citation6 Historically, male doctors in Morocco seldom provided obstetric care, particularly since there were better-paying alternatives. However, partly in response to an increase in pregnancy rates, medical officers and nurses, whether trained or not in obstetrics and gynaecology, gradually took over the responsibilities of midwives, mostly in urban areas. In the rural areas, although kablas were the ones who attended expectant mothers, they were required to report to a medical officer so that the latter could determine how their care was to be carried out, as needed. This was in line with the dahir (law promulgated by the King) which dates back to 1960.Citation7 This law conferred ultimate recognition and authority on the medical officer (usually a man) over the midwife (usually a woman). This was and is widely accepted in Moroccan society and also inadvertently reinforces prevailing gender constructs.

In the 1960s, the Ministry of Health established a two-year midwifery training programme at the graduate level, at the École de Cadres in Rabat, to address the shortage of skilled birth attendants. Nurses could access this programme after completing a three-year undergraduate degree in nursing and allied health subjects. Because of the same sorts of gender issues that limited the success of moualidates training, this graduate programme was also unable to train large enough numbers of midwives to fill Moroccan needs, especially in the rural areas. Indeed, an average of only seven midwives per year earned a graduate diploma from this school, with a total of only 239 graduates in the 30 years from 1964 to 1995. Furthermore, its graduates usually ended up practising in urban centres, defeating the primary purpose of locating midwives in regions all over the country.Citation5

By 1986, the Ministry of Health had changed gears and its Training Division began to promote midwifery training to nurses in nursing schools across Morocco, provided as part of a two-year programme at the undergraduate level, which included a specialism in obstetrics. In 1988, women who had completed their third year in secondary school were eligible to enrol for this specialist training. A total of 820 nurse-midwives graduated from this programme between 1986–1991.Citation8

In 1993, an in-depth reform of training programmes for the range of allied health professionals, including those for nurse-midwives, was carried out.Citation9 After 1993, midwifery training was unfortunately no longer offered at the graduate level. Instead, a three-year undergraduate programme was set up for these health professionals, including for nurses, by the Instituts de Formation aux Carrières de Santé (IFCS, Training Institutes for Allied Health Professionals).Citation10 Today, this training is offered at eight Regional Training Institutes in Agadir, Casablanca, Fes, Marraketch, Meknes, Oujda, Rabat and Tetouan. Since 1997, an average of 200 nurse-midwives per year have been graduating from the programme across the country, with 212, 293 and 332 graduates in 2002, 2003 and 2004, respectively. The statistics are encouraging, in that between 1963 and 2003 a total of 2,495 midwives were trained in the eight Regional Institutes.Citation11 In addition, the quality of professional practice of these new graduates was evaluated favourably. The evaluation took place in selected rural (Azilal, El Haouz, Chicaoua, Sidi Youssef Ben Ali) as well as urban areas (Menara, Medina and Syba). However, while the midwives' technical competency was demonstrated, a holistic approach based on women's needs was still lacking.Citation12 Moreover, staff turnover and an early retirement package have meant that across the country, approximately 200 midwives a year have been leaving their posts. Thus, the number of midwives may have remained stagnant for some time, at less than a total of 2,000.Citation13

In October 2004, there were 1,621 midwives working in the public sector and 665,396 births.Citation14 This gives an estimated ratio of one midwife to 289 births. The World Health Organization (WHO) standard, by comparison, is one midwife to 200 births. This ratio may seem too high for Morocco to aspire to, especially given the risks and the co-morbidities that occur in the rural areas. However, Morocco is on the right path with regard to the total number of midwives. Despite the current shortage of nurse-midwives, in the next five years the WHO standard could still be reached. Based on a report by the Commission on Human Resources, some 2,528 midwives will be required in Morocco to attend all births. There is thus a current shortage of approximately 950 midwives. While reaching this number is uncertain, the Training Division is working hard to attract women into the programme, in order to meet the WHO standard by 2010.Citation14 Nevertheless, an appropriate balance in the geographic distribution of midwives between urban and rural areas is as important as their overall numbers. In fact, the WHO recommendation is for there to be skilled attendants (i.e. obstetricians and midwives) at 90% of births by 2015 in regions where they were not previously available. It must be remembered that in 1997, 40% of births in rural Morocco were not attended by a skilled attendant.Citation5 Moreover, despite newly graduating midwives being given an initial assignment by the Training Division to work in a rural area, most have got married by the time they complete their training and leaving their households to be posted to a rural area is impossible.Citation15

In 2000, a Commission, jointly appointed by the Ministry of Health (responsible for the training of nurse-midwives at the institute level) and the Ministry of Education (responsible for the training at university level) revised the curricula and pedagogical approaches to midwifery training. Gynaecologists, obstetricians and nurse-midwives were part of this Commission. While the content has been updated, a technical focus, especially with regard to the biomedical treatment of disease, still predominates, rather than a preventive and health promotion approach within the overall experience of pregnancy. This has been sustained by the fact that the social dimensions of health are still perceived to be of secondary concern, and that the mastery of practical and technical skills confers greater prestige upon caregivers. This translates into a focus on the technical aspects of delivery itself, rather than encompassing the emotional needs of the future mother. Furthermore, medical officers, whether trained or not in gynaecology and obstetrics, still need to be present to “oversee” the care given by the nurse-midwife – independently of the experience and training she may have. The usual scenario is that the nurse-midwife proceeds in the “technical” assessment of the woman in labour and refers to the medical officer, still usually a man, in order for him to prescribe the next steps (usually those recommended by the nurse-midwife). Increasingly, in the rural areas, nurse-midwives have sharpened their skills to address complications. Yet, the medical officer is the one who is officially recognised as the ultimate decision-maker, especially in potentially litigious situations.

Midwifery, gender relations and women's status in Morocco

With this as backdrop, a policy of promoting home-based antenatal care and deliveries, attended by skilled midwives, is seen by some as a more conducive strategy to allow midwives to shape women's care, according to women's needs, resources and social constraints, because the domestic realm is women-dominated. However, this may also compound and inadvertently reinforce prevailing gender constructs as well as entrench the marginalisation of women from access to integrated maternity care and visibility within the broader context of Moroccan society.Citation1Citation2Citation16 In the literature, the political nature of gendered power relations, and representation and visibility of women within the context of women's sexual and reproductive health care, has been widely discussed.Citation17Citation18Citation19 Under current Ministry of Health policy in Morocco, nurse-midwives' decisions regarding obstetric care are recognised as paramount if and only if they are made in the absence of a general practitioner or gynaecologist.

The recent National Health Survey (2003—2004)Citation20 noted that the hierarchical relationship between midwives and obstetricians increasingly and subtly extends into interactions among midwives themselves, as well as in relation to other cadres of health professionals. Lack of regard for peers, poor collaboration and contemptuous attitudes on the part of midwives have been reported, as well as feelings of fear and distress.Citation3 As a result, midwives unwittingly contribute to the lack of recognition of their specific professional contribution to health care.

A multi-dimensional concept of women's sexual and reproductive health care is deeply embedded in the philosophy of midwifery practice, however. The primary goal of midwifery is the provision of women-sensitive, women-centred care, in which it is critical to include the male partner (usually the husband) in the experience of pregnancy, birth and parenting.Citation18Citation21Citation22 In this context, midwifery is a response to inequalities in women's access to the resources, opportunities and social conditions necessary for health. Midwifery care aims to reduce death and morbidity due to inadequate care for women's sexual and reproductive health needs, which can only be achieved through the elevation of women's needs and interests in all sectors of society.Citation17Citation23

Concern for the importance of social roles in promoting reproductive and maternal health should not be shouldered exclusively by women health care providers. However, the social construction of gender relations in Morocco, particularly concerning the role of women in the private and public spheres, often prohibits male health care providers from recognising the diverse contributions of women, which, in turn, may affect women's clinical experiences and health outcomes. For instance, delivery in the recumbent or supine position, placing women's feet in stirrups, routine episiotomies, frequent caesarean sections and the overwhelming use of technical terms around women who cannot understand them are still current practices. They underlie the reasons why home delivery often represents a form of re-assuring refuge, especially for the most vulnerable women.

Another recurrent issue of concern among women and providers of sexual and reproductive health care is the role of men in relation to family planning. Men in Morocco continue, whether overtly or more subtly, to control women's fertility. A number of family planning methods are still met with strong reluctance, such as the intra-uterine device and even condoms.Citation8Citation16Citation17Citation24 Realities such as these, which arise from prevailing social norms, create complexities for women wishing to control their own bodies. They also make it more difficult for health care professionals to implement family planning activities. In spite of apparent male control over women's fertility, however, pregnancy and delivery are viewed as natural life experiences that women must deal with discreetly and with as much privacy as possible.

Improving women's access to midwifery care

Over and above the many issues related to women's lack of control over their own fertility, midwives raise the additional concern that demands for discretion and privacy do not allow women to seek an appropriate and timely response in cases of obstetric complications. In this respect, Dialmy calls attention to:

“…the current inverse care law, whereby those who are in most need of health care services, mainly in rural areas, receive the least; this reduced level of use is not necessarily a sign of resistance or a deliberate choice.”Citation24 [free translation]

The maternal mortality ratio speaks volumes. The most recent statistics, for 2003—04, estimate 267 deaths per 100,000 live births in rural areas versus 187 in urban areas.Citation20 Many factors are undoubtedly associated with such inequalities, including the presence of co-morbidities, poverty, lack of financial resources, financial dependency, and geographic determinants of access to appropriate maternal and child services.Citation2Citation16Citation24 But increasing the number of adequately trained nurse-midwives, as well as working on their recognition, should benefit those who most need these services to prevent complications and death. Then, it is plausible that the gap between mortality rates in rural and urban areas might progressively be reduced.

From a policy perspective, increasing gender sensitivity with regard to professional health care for women would improve access to and quality of care. From a service design perspective, this would mean addressing persistent inadequacies such as the limited opening hours for ambulatory care that do not respect the dynamic of the family and the prohibitive cost of prescription drugs. With regard to maternity care, the cost of unnecessary, repeated ultrasounds may reduce what is spent on other aspects of care, particularly when the woman's health is not a priority in the household budget. Such a context is reinforced by Moroccan women's financial dependence.Citation2Citation17Citation24Footnote1

Midwives: a source of power to be appropriated by, for and with women

The conceptualisation of women's sexual and reproductive health within midwifery extends far beyond sex and reproduction, and the objectives of midwifery encompass more than the absence of disease. Rather, as endorsed and advocated by many international agencies, research and development bodies, sexual and reproductive health must be addressed through a multi-sectoral, lifetime commitment to women's health in the context of socio-cultural conditions. This commitment includes taking into account the milieu in which women live, gender norms and perceptions, women's representation and leadership in political and economic forums and an overall related commitment to gender-equitable access to resources and opportunities. In Morocco, improving women's sexual and reproductive health includes incorporating more opportunities for supporting women's personal values and choices.Citation26

The Moroccan experience highlights the importance of understanding how the globally dominant medical model shapes midwifery practices and, ultimately, the extent to which midwifery contributes to gender-sensitive health care for Moroccan women. One of the current challenges for midwives in Morocco is the creative reconciliation, with women, of the best elements of the medical model and local knowledge and practices, in order to engender new patterns of reproductive and maternal health care.Citation26 This vision coincides with culturally relevant health practices and attention to women's values, expressions and behaviours regarding pregnancy, birth and the post-partum period.Citation27Citation28

This vision of women-centred health care, as advocated by midwifery and other health care professionals, is in line with the Moroccan National Strategic Plan,Citation29 which grants a special place to the promotion of women's needs and interests in social planning. Several new government policies reflect increased attention to women's needs and interests, including the 2004 Family Code (Code de la Famille), which recognises women's rights in terms of personal status, and the creation of a Ministry of the Family, Solidarity and Social Action, to boost overall civil society activities. Also, following the 2003 parliamentary elections, a quota system made it possible for more women to enter Parliament, with the number of seats held by women increasing from 2 to 33.Citation30 Even more recently, since February 2006, midwives may be eligible for reimbursement should a medical doctor be unavailable.

It is crucial that the government also commit itself to investing in the public health infrastructure, as encouraged by the Millennium Development Goals. In fact, midwives are recognised by the World Health Organization as a “key group in reducing unacceptably high rates of death and injury in women as a result of childbearing”.Citation18Citation31

Professional organisations and networks: natural allies

The establishment of collaborative networks, joint projects and meetings within the health care profession in Morocco is also important, as is the creation of networks and partnerships across the international midwifery profession.

Created in 1990, the Association des Sages-Femmes Marocaines (AMSF, Moroccan Midwives Association) has focused primarily on continuing education for midwives (in partnership with the American College of Midwives and USAID). The AMSF has been active in training and career development issues, including curriculum review and increasing the quantity and quality of midwifery training, and has worked with a number of non-governmental agencies to provide education and care to vulnerable and underprivileged groups.

Actions taken by the AMSF in favour of a systematic recognition of midwifery as a professional practice have been met with fierce opposition from the Moroccan College of Gynaecologists and Obstetricians, particularly in the private sector. This is partly due to the highly gendered hierarchy within the Moroccan medical system, but also because of the underlying influence of the regulations of the dahir in 1960, which sanctioned medical dominance over all other allied health care professions, including nursing and midwifery. Joint efforts are required between midwifery, nursing and allied health care professionals, in partnership with the medical profession, to challenge this norm.

Over the past few years, partnerships with international professional associations such as the Secretariat International des Infirmières et Infirmiers de l'Espace Francophone (SIDIIEF, International Secretariat of Nurses in the French-speaking World), the American College of Midwives, the International Confederation of Midwives and the Sages-Femmes du Monde (Midwives of the World) have led to positive outcomes. Not least they have enabled the AMSF to understand the challenges encountered by the midwifery profession elsewhere in the world. They have also enabled the establishment of a stronger relationship with the Association Marocaine des Sciences Infirmières et Techniques Sanitaires (AMSITS, Moroccan Association of Nursing and Allied Health) to establish specific strategies and a framework for promoting the professional recognition, autonomy and visibility of midwifery in Morocco. Such partnerships within the country are not customary, but midwives must make alliances with those who can provide an additional voice – until such time as the voices of medical professional associations in Morocco join with our own.

In conclusion

Contemporary midwifery practice in Morocco is located at several contentious crossroads in a society in which actions and relationships between women and men are strongly regulated by a gender hierarchy. This hierarchy is strongly felt by midwifery, a profession desperately seeking more autonomy and recognition. The present discussion leads us to call for a re-appropriation strategy for midwifery practice in partnership with women in the community, the primary recipients of midwifery care. The challenges in the implementation of standardised midwifery practice include ensuring an adequate disciplinary link with the medical community and recognition and treatment of midwives as competent, skilled and valuable partners within a broader team of health care providers, male as well as female, including nurses, gynaecologists and obstetricians. It is on this basis that the process of developing a humanised midwifery practice can progressively evolve.

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to the editors of International Midwifery for their kind permission to present a longer version of the original paper published in that journal: Temmar F, Vissandjée B, Kérouac S. Strengthening midwifery practices in Morocco: a gender perspective. International Midwifery 2005;18(1):8–9. The first author of this paper is a nurse-midwife and one of the founders of the Moroccan Association of Midwives in 1990, with long experience in the field. She has also been active in designing the training of nurse-midwives at the baccalaureate level in Morocco. Special thanks to Suzanne Kérouac, without whose constant help and support this paper could not have been completed. We all, the first author in particular, would like to acknowledge the invaluable contribution of a large number of midwives, women and mothers – yesterday, today and tomorrow.

Notes

1 In 2005, the Ministry of Health issued a decree allowing each pregnant woman to have an ultrasound scan which would be eligible for reimbursement by her health insurance.Citation25

References

- P Bourdieu. La domination masculine. 1998; Édition du Seuil: Paris.

- H Filali, F Temmar. Étude qualitative sur les conditions d'exercice des sages-femmes. Régions de Marrakech, Tensift, Alhaouz et province d'Azilal. Projet FNUAP MOR/PO1/02. 2003; Ministère de la Santé, Division de la Formation: Maroc.

- W Bakhach, R Benmchich, A Elghaouti. Insertion des sages femmes formées depuis 1997 dans le milieu de travail, région Tanger – Tétouan, mémoire non publié. 2003; Institut de Formation aux Carrières de Santé: Rabat, Maroc.

- United Nations General Conference. The Maternity Protection Convention Revised and Recommendation. 1952; UN: Geneva.

- F Temmar. La formation de la sage-femme au Maroc: entre les besoins en santé reproductive et les défis de la profession. 2003; Communication au 1er congrès des sages-femmes de Tétouan: Tétouan.

- F Temmar, X Kamri. Nouvelles stratégies de développement de la profession de sage-femme au Maroc. 1996; 6eCongrès Médical: Rabat.

- His Majesty the King Mohammed V. The dahir – a royal decree – Code of Personal Status. Rabat, Morocco, 1957–58.

- Commission Responsible for Developing Midwifery Training Programmes, 1999.

- Ministry of Education. Decree No. 2-93-602, 29 October 1993.

- Ministry of Education. Bill 001– Higher Education Reform, 2000. Rabat, 2000.

- Système d'information, Division de la formation, Ministère de la santé, 2004.

- Division de la formation, Ministère de la santé. Rapport d'activités du projet MSP/FNUAP MOR/92/POI visant l'amélioration de la qualité de la formation des sages-femmes, Rabat, 1995.

- Système d'information, Ministère de la santé. Santé en chiffres, 2001.

- Système d'information, Ministère de la santé. Santé en chiffres, 2004.

- BF Anderson. Public health professor teaches classes in Mexico, Morocco, Tibet, Tunisia and Turkey. Today. 2001. At: <http://www.llu.edu/news/today/nov2801/sph.html. >. Accessed September 2005.

- R Boumia. Les connaissances, les attitudes et les pratiques des prestataires des services de santé reproductive par rapport à l'approche genre; étude qualitative réalisée dans le cadre du projet: genre et développement. 2001; Association marocaine de planification familiale: Rabat.

- M Berer. Access to reproductive health: a question of distributive justice. Reproductive Health Matters. 7(14): 1999; 8–13.

- L Barclay. Midwifery in Australia and surrounding regions: dilemmas, debates and developments. Reproductive Health Matters. 6(11): 1998; 149–156.

- M Lock, P Kaufert. Pragmatic Women and Body Politics. 1998; University of California Press: Berkeley.

- Ministry of Health. National Health Survey 2003–2004. Rabat, 2004.

- P Farmer. Pathologies of Power: Health, Human Rights and the New War on the Poor. 2003; University of California Press: Berkeley.

- JY Kim, JV Millen, A Irwin. Dying for Growth: Global Inequality and the Health of the Poor. 2000; Common Courage Press: Bangor.

- World Health Organization. Make Every Mother and Child Count. Report. 2005; WHO: Geneva. At: <http://www.who.int/whr/2005/en/. >. Accessed August 2005.

- A Dialmy. La gestion socioculturelle de la complication obstétricale dans les régions de Fes-Boulemane et Taza. Alhoceïma – Taounate. 2000; Division de la population, Ministère de la santé: Rabat.

- Ministère de la santé. Loi 65.00. Couverture médicale de base, 2005.

- C Makhlouf Obermeyer. Pluralism and pragmatism: knowledge and practice of birth in Morocco. Medical Anthropology Quarterly. 14(2): 2000; 180–201.

- M Leininger. Culture care theory: a major contribution to advance transcultural nursing knowledge and practices. Journal of Transcultural Nursing. 13(3): 2002; 189–192.

- MA Seisser. Madeleine Leininger on transcultural nursing and culturally competent care [Interview]. Journal for Healthcare Quality. 24(2): 2000; 18–21.

- Statement on the National Strategic Plan. 2003; Government of Morocco: Rabat.

- Population and Family Health Survey 2003–2004. 2004; Ministry of Health: Rabat.

- The 10/90 Report on Health Research 2003–2004. Global Health Forum for Research: Helping Correct the 10/90 Gap. At: <www.globalforumhealth.org>. Accessed April 2005.