Abstract

Promotion of male condoms and voluntary counselling and testing for HIV (VCT) have been cornerstones of Kenya’s fight against the HIV epidemic. This paper argues that there is an urgent need to promote the female condom in Kenya through VCT centres, which are rapidly being scaled-up across the country and are reaching increasingly large numbers of people. Training of counsellors using a vaginal demonstration model is needed, as well an adequate supply of free female condoms. In a study in five VCT centres, however, counsellors reported that most people they counselled believed female condoms were “not as good” as male condoms. In fact, many clients had little or no knowledge or experience of female condoms. Counsellors’ knowledge too was largely based on hearsay; most felt constrained by lack of experience and had many doubts about female condoms, which need addressing. Additional areas that require attention in training include how to re-use female condoms and the value of female condoms for contraception. VCT counsellors in Kenya already promote male condoms as a routine part of risk reduction counselling alongside HIV testing. This cadre, trained in client-centred approaches, has the potential to champion female condoms as well, to better support the right to a healthy and safe sex life.

Résumé

La promotion des préservatifs masculins et les services de conseils et dépistage volontaire du VIH (CDV) sont des pierres angulaires de la lutte contre l’épidémie de VIH au Kenya. Cet article avance qu’il est urgent de promouvoir le préservatif féminin au Kenya dans les centres de CDV qui se multiplient rapidement et atteignent un nombre croissant de personnes. Il faut former des conseillers à l’utilisation d’un modèle de démonstration vaginale et disposer d’un approvisionnement suffisant de préservatifs féminins gratuits. Pourtant, dans une étude de cinq centres de CDV, les conseillers ont indiqué que la plupart de leurs clients pensaient que les préservatifs féminins n’étaient pas « aussi bons » que les préservatifs masculins. En fait, beaucoup de clients ne savaient rien ou presque des préservatifs féminins. Les connaissances des conseillers étaient aussi trop vagues, la plupart se sentaient limités par le manque d’expérience et avaient de nombreux doutes sur les préservatifs féminins, qu’il faudra aborder. La formation devra également porter sur la réutilisation des préservatifs féminins et leur intérêt pour la contraception. Les conseillers de CDV au Kenya prônent déjà les préservatifs masculins dans le cadre de la réduction des risques, parallèlement au dépistage du VIH. Ces personnels, formés à des approches axées sur les clients, ont le potentiel de promouvoir aussi les préservatifs féminins, afin de mieux soutenir le droit à une vie sexuelle saine et sûre.

Resumen

La promoción del condón masculino y la asesoría y pruebas voluntarias del VIH (APV) han sido unos pilares de la lucha de Kenia contra la epidemia del VIH. En este artículo se argumenta que existe la necesidad urgente de promover el condón femenino en Kenia mediante centros de APV, los cuales se están multiplicando rápidamente en todo el país y cada vez más alcanzan a un mayor número de personas. Para ello, se necesita capacitar a los consejeros utilizando un modelo de demostración vaginal, así como un suministro adecuado de condones femeninos gratis. No obstante, en un estudio realizado en cinco centros de APV, los consejeros informaron que la mayoría de sus clientes creían que el condón femenino “no es tan bueno” como el masculino. Es más, muchos tenían poco o ningún conocimiento de la experiencia del condón femenino. Los conocimientos de los consejeros también se basaban principalmente en habladurías; la mayoría se sentía limitada por la falta de experiencia y tenía muchas dudas en cuanto al condón femenino, las cuales deben ser aclaradas. Otras áreas que debe abarcar la capacitación son cómo reutilizar el condón femenino y su valor para la anticoncepción. Los consejeros de APV en Kenia ya promueven el condón masculino como parte rutinaria de la consejería brindada para disminuir los riesgos, junto con las pruebas de VIH. Esta categoría de personal, capacitada en estrategias centradas en los clientes, tiene el potencial de promover el condón femenino también, con el fin de apoyar mejor el derecho a una vida sexual saludable y segura.

A cornerstone of Kenya’s HIV prevention policy has been the promotion and use of male condoms,Citation1 under which the Government aims to ensure an adequate national supply of condoms and access to them. It also aims to support education and advocacy to increase condom use. Following the examples of Brazil, Ghana, Zimbabwe and South Africa, the government agreed to support the distribution of female condoms as well, as a means of empowering women to practise safer sex.Citation2 In 2004, a stakeholders meeting for introducing the female condom in Kenya was held.Citation3 Condom quality in Kenya is assured through the National Quality Control Laboratory. Sales and private distribution of both female and male condoms are regulated, so that only products meeting WHO standards are allowed for sale and use.

Through use of the media, the Government of Kenya has promoted public confidence in the quality of condoms, using lessons learned from social marketing. As a result, confidence in branded condoms such as Trust has grown. Condoms have been further popularised through a combination of communications strategies, subsidised prices and efficient distribution networks.Citation4 By comparison, popularisation of female condoms has lagged behind,Citation5 and they remain largely unknown and unavailable. Although the Government has taken some steps to subsidise the cost of female condoms, and they are provided free in a number of STI clinics and sex worker outreach programmes, the current retail price is still about ten times that of male condoms. This is a significant problem in countries with high HIV prevalence and high levels of poverty, especially among women.Citation6

Another key strategy in Kenya’s fight against HIV has been the rapid scale-up of voluntary counselling and testing services (VCT).Citation7 To this end, over 650 VCT sites have been registered nationally. A standard 126-hour training package for VCT counsellors, followed by a period of observed practice, has also been developed.Citation8 Integral to the VCT protocol, condoms are discussed as a routine part of pre-test counselling process, with the focus largely on male condoms.Citation9 The aim is to provide people with an opportunity to assess their HIV risk and explore the options available to them to reduce risk. Putting on and taking off a male condom is demonstrated using a penile model, and male condoms are provided free (except by the 17 faith-based VCT centres).

Analysis of data from 35 VCT sites in Kenya in 2003 showed that not only were women less likely than men to attend for VCT, they were also less likely to take condoms home or to have used them. Counselling in the context of VCT was nevertheless shown to play a role in male condom uptakeCitation10 and we believe it has the potential to influence the uptake of female condoms too.

Studies from AfricaCitation11Citation12 have focused on the perspectives of women and men who have used female condoms or who are potential users. There is also evidence that the option of using female condoms empowers sex workers to have safer sex with some clients who refuse male condoms.Citation13 Citation14 Citation15

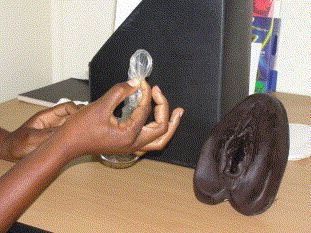

Much less has been published on the perspectives and role of health care workers and counsellors in female condom promotion,Citation16 especially in VCT services. This is a missed opportunity. Health care workers in general and VCT counsellors in particular have the potential to promote female condoms alongside male condoms to large numbers of people. Following training of counsellors with vaginal models and practical support, as well an adequate supply of free female condoms in one VCT site in a high density peri-urban area in Nairobi in 2004, counsellors noted a steady increase in uptake of female condoms (Miriam Taegtmeyer, et al. Unpublished data, February 2005).

This experience provided the impetus for a small study in January–February 2005 in five stand-alone VCT centres in Nyanza, Coast and Nairobi provinces, where all the counsellors had had counselling training by a Kenyan non-governmental organisation called Liverpool VCT, Care and Treatment. In-depth interviews were conducted with 11 VCT counsellors (five women, six men) from the five centres to explore whether their own knowledge, values and attitudes influenced discussion, demonstration and uptake of female condoms. Discussions were also held with the members of the five post-test clubs based at the VCT centres, to generate a greater understanding of the factors influencing the uptake of female condoms during VCT.

VCT counsellors’ and clients’ perceptions of female condoms

All five centres normally dispensed free male condoms and all had penile models for male condom demonstration. Female condoms were not supplied regularly except at the onset of the study.

Many participants recognised the need for female condoms and their usefulness in protecting against infection. Male clients all reported a willingness to try female condoms and felt they had a certain novelty value. Counsellors and women clients agreed that female condoms were important in empowering women to negotiate for safer sex. Some counsellors stressed that in certain situations female condoms might be particularly appropriate, for example when a husband or partner was drunk and demanding sex.

On the other hand, the VCT counsellors reported that most of the people they counselled believed that female condoms were “not as good” as male condoms. The female counsellors also seemed not to be comfortable with female condoms themselves as women. For example, one thought the ring might cause “some kind of irritation” during insertion, though she did not say she knew anyone who had had that experience. Although they said they were advocating for female condom use, then, the counsellors often had big doubts themselves, for example:

“I have issues with female condoms, I don’t like them that much because they are big and I think while using them, one can get infection. Anyway, let’s say you want to put it on, if you are not used to doing this (inaweza kukupatia shida) it can give you problems And the fact that it’s big like a paper bag. It’s too big compared to the male condom”. (Female counsellor, Malindi)

In fact, many clients had little or no knowledge of female condoms or experience of handling them. The counsellors’ knowledge too was largely based on hearsay, and most felt constrained by their own lack of experience and knowledge. During the interviews, they often directed questions back to the interviewers, indicating that they were not sure about issues such as re-use of female condoms, lubricants or use for anal sex.

Female condom discussions and demonstrations that we observed varied from one counsellor to another and also with different women. Some counsellors said they would always discuss and demonstrate the female condom, but a few said they would only do so if women expressed an interest. In general, the counsellors felt there was no need to talk about female condoms because normally they were not in a position to offer them to anyone who requested them. During the study all five centres had a good supply of female condoms but this was not the norm at other sites.

Discussion and recommendations

This small study identified a clear need for further training to improve knowledge of and ability to demonstrate female condoms. Already central to the training approach is the opportunity for counsellors to examine and understand their own values and attitudes and how these might affect their interactions with different clients. The current VCT training in Kenya uses reflective, adult learning methodologies. It also relies on regular supervision and refresher courses. Training has recently been updated, following insights from operations research,Citation10 to incorporate sessions in which counsellors can reflect on their own values regarding male and female condoms, teach them to actively promote condoms, train clients to use them and involve their partners as well.

A concrete example of the link between training and counselling was what came out of the distribution of female condoms to counsellor trainees (both male and female) to try out at home over a weekend during a training course. This triggered a lot of discussion on the following Monday, in which some female counsellors said they had been completely unable to bring up the subject, while others had positive responses and made light-hearted jokes, allowing a route into discussion on how this experience might affect their counselling with clients. Additional areas that require attention in training include teaching women how to re-use female condomsCitation17 and the value of female condoms for contraception, as both were seen by counsellors as areas of ambiguity and debate.

Female condoms in Kenya are procured separately from male condoms. Following advocacy from the Kenyan Department of Reproductive Health and implementing partners in HIV/AIDS and family planning, the United National Family Planning Association purchased two million female condoms for Kenya in early 2006 and has made a commitment to do this for the next two years too. Efforts are required for sustained government procurement policies that are responsive to new developments, such as making the second generation female condom available.Citation18 Another layer of advocacy is needed to ensure that female condoms are disbursed to VCT sites in Kenya, accompanied by demonstration models (). Procurement strategies also need to be situated within broader approaches to improving the access of poor and socially-excluded people to sexual and reproductive health services and technologies.Citation19

The rapid expansion of Kenya’s prevention of mother-to-child transmission programmes has seen more and more women in Kenya testing for HIV.Citation20 However, the aim of these programmes is to ensure an HIV-negative infant. There is little opportunity at antenatal screening and treatment for discussion and demonstration of condoms or any significant prevention counselling. As a result, efforts are being made to encourage women to come for VCT independently of pregnancy. Policy changes include a new approach to media campaigns for VCT, improved access through longer opening hours, not charging user fees and increasing access to mobile VCT services in rural areas.

VCT counsellors already promote male condoms as a routine part of risk reduction counselling before and after HIV testing. This cadre, trained in client-centred approaches and gender relations, has the potential to champion female condoms as well. The integration of female condoms into VCT risk reduction counselling comes at a time of rapid scale-up of HIV services across the world. The integration of female condom provision into VCT programmes has the potential to support the right to a healthy and safe sex life.

References

- Government of Kenya. National Condom Policy and Strategy 2001–2005. 2001; National AIDS Control Council, Ministry of Health: Nairobi.

- Warren M, Philpott A, 2001. Expanding safer sex options: introducing the female condom into national programmes. Reproductive Health Matters 11(21):130–39

- WHO, UNAIDS. The Female Condom: A Guide for Planning and Programming. At: <http://data.unaids.org/Publications/IRC-pub01/JC301-FemCondGuide_en.pdf. >. Accessed August 2006.

- UNAIDS. Social Marketing: An Effective Tool in the Global Response to HIV/AIDS. Best Practice Collection. 1998; UNAIDS: Geneva. At: <http://data.unaids.org/Publications/IRC-pub01/JC167-SocMarketing_en.pdf>. Accessed August 2006.

- SS Bull, J Cohen, C Ortiz. The POWER campaign for promotion of female and male condoms: audience research and campaign development. Health Communication. 14(4): 2002; 475–491.

- D Kerrigan, JM Ellen, L Moreno. Environmental–structural factors significantly associated with consistent condom use among female sex workers in the Dominican Republic. AIDS. 17(3): 2003; 415–423.

- National AIDS and STDs Control Programme. Kenya National Strategy for VCT Scale-up 2003-2007. 2003; Ministry of Health: Nairobi.

- A Eden, M Taegtmeyer. Kenya National Manual for Training Counsellors in Voluntary Counselling and Testing for HIV. Part 1. 2003; National AIDS and STD Control Programme: Nairobi.

- Government of Kenya. National Guidelines for Voluntary Counselling and Testing. 2001; National AIDS and STD Control Programme, Ministry of Health: Nairobi.

- M Taegtmeyer, N Kilonzo, L Mung’ala. Using gender analysis to build voluntary counselling and testing responses in Kenya. Transcripts of Royal Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene. 100(4): 2006; 305–311.

- E Musaba, CS Morrison, MR Sunkutu. Long-term use of the female condom among couples at high risk of human immunodeficiency virus infection in Zambia. Sexually Transmitted Diseases. 25(5): 1998; 260–264.

- S Ray, M Bassett, C Maposhere. Acceptability of the female condom in Zimbabwe: positive but male-centred responses. Reproductive Health Matters. 3(5): 1995; 68–78.

- D Kerrigan, L Moreno, S Rosario. Environmental–structural interventions to reduce HIV/STI risk among female sex workers in the Dominican Republic. American Journal of Public Health. 96(1): 2006; 120–125.

- C Yimin, L Zhaohui, W Xainmi. Use of the female condom among sex workers in China. International Journal of Gynecology and Obstetrics. 81(2): 2003; 233–239.

- S Ray, J van der Wijgert, P Mason. Constraints faced by sex workers in use of female and male condoms for safer sex in urban Zimbabwe. Journal of Urban Health. 78(4): 2001; 581–592.

- JE Mantell, E Scheepers, QA Karim. Introducing the female condom through the public health sector: experiences from South Africa. AIDS Care. 12(5): 2000; 589–601.

- World Health Organization. Considerations regarding re-use of the female condom. Information update, 10 July 2002. Reproductive Health Matters. 10(20): 2002; 182–186.

- T Nakari. Second generation female condom available [Letter]. Reproductive Health Matters. 14(28): 2006; 180.

- Realising Rights: A Research Programme Consortium. Improving sexual and reproductive health in poor and vulnerable populations. At: <www.realising-rights.org/research.htm. >. Accessed August 2006.

- National AIDS and STD Control Programme. AIDS in Kenya: Trends, Interventions and Impact. 7th ed, 2005; Ministry of Health: Nairobi.