Abstract

This article presents findings from a pilot intervention in 2005–6 to promote gender equity among young men from low-income communities in Mumbai, India. The project involved formative work on gender, sexuality and masculinity, and educational activities with 126 young men, aged 18–29, over a six-month period. The programme of activities was called Yari-dosti, which is Hindi for friendship or bonding among men, and was adapted from a Brazilian intervention. Pre-and post-intervention surveys, including measures of attitudes towards gender norms using the Gender Equitable Men (GEM) Scale and other key outcomes, qualitative interviews with 31 participants, monitoring and observations were used as evaluation tools. Almost all the young men actively participated in the activities and appreciated the intervention. It was often the first time they had had the opportunity to discuss and reflect on these issues. The interviews showed that attitudes towards gender and sexuality, as reported behaviour in relationships, had often changed. A survey two months later also showed a significant decrease in support for inequitable gender norms and sexual harassment of girls and women. The results suggest that the pilot was successful in reaching and engaging young men to critically discuss gender dynamics and health risk, and in shifting key gender-related attitudes.

Résumé

Cet article présente les conclusions d’une intervention pilote menée en 2005-06 pour promouvoir l’égalité des sexes chez les jeunes hommes de communautés à faible revenu à Mumbai, Inde. Le projet comportait une formation sur la parité, la sexualité et la masculinité, et des activités éducatives avec 126 hommes, âgés de 18 à 29 ans, pendant six mois. Le programme, appelé Yari-dosti, mot hindi signifiant amitié ou liens masculins, s’inspirait d’un projet brésilien. L’évaluation a utilisé des enquêtes avant et après l’intervention avec l’échelle GEM (Gender Equitable Men) et d’autres résultats clés, des entretiens qualitatifs avec 31 participants, un suivi et des observations. Presque tous les hommes ont participé activement et ont apprécié l’intervention. C’était souvent la première fois qu’ils pouvaient parler de manière critique de ces questions. Les entretiens ont montré que les attitudes à l’égard de la parité et de la sexualité, comme le comportement dans les relations, avaient souvent changé. Une enquête deux mois plus tard a révélé une diminution sensible du soutien aux normes d’inégalité sexuelle et moins de harcèlement sexuel des jeunes filles et des femmes. Les résultats indiquent que l’intervention est parvenue à atteindre les jeunes hommes et à les convaincre de parler de la dynamique entre les sexes et du risque sanitaire, et à modifier des attitudes clés liées à la parité.

Resumen

En este artículo se presentan los hallazgos de una intervención piloto realizada en 2005-06 para promover la equidad de género entre hombres jóvenes de comunidades de bajos ingresos en Mumbai, India. El proyecto implicó formatión sobre el género, la sexualidad y la masculinidad y actividades educativas con 126 hombres jóvenes, de 18 a 29 años de edad, durante seis meses. El programa denominado Yari-dosti, término hindi que significa amistad o vinculación entre hombres fue adaptado de una intervención brasilera. Se utilizaron encuestas pre-y post-intervención, incluidas las medidas de actitudes hacia las normas de género utilizando una escala llamada Gender Equitable Men (GEM) y otros resultados clave, entrevistas cualitativas con 31 participantes, monitoreo y observaciones. Casi todos los jóvenes participaron al máximo en las actividades y agradecieron la intervención. Para muchos, ésta era su primera oportunidad de discutir estos asuntos. Las entrevistas mostraron que las actitudes hacia el género y la sexualidad, como comportamiento en las relaciones, con frecuencia habían cambiado. Una encuesta realizada dos meses después mostró una disminución significante en el apoyo de normas de género no equitativas y menos acoso sexual de las niñas y mujeres. Los resultados indican que el piloto motivó a los jóvenes a analizar las dinámicas de género y el riesgo a la salud y cambiar las actitudes relacionadas con el género.

In India the number of people living with HIV is estimated to be 5.1 million.Citation1 Almost half of new HIV infections are believed to occur among young men below age 30.Citation2 An important factor influencing young men’s HIV risk in India is early socialisation in notions of masculinity that promote inequitable gender-related attitudes and behaviours. Young men in India, by and large, mature and develop in a male-dominated context, with little contact with young women and virtually no sex education.Citation3Citation4 While this pattern may be changing for a small minority of urban young men of upper socio-economic class, it has not changed for the vast majority. Most boys develop a sense of masculinity characterised by male dominance in the sexual arena and other areas. It is argued that challenging prevailing views of masculinity (and femininity) is essential to promoting sexual health and reducing vulnerability for both young men and women.Citation5

Throughout the world, as in India, expectations that women must defer to male authority support practices such as early marriage and coercive sexual relations.Citation6Citation7 Pressure from peers and adults often encourages men to engage in risky sexual behaviour, e.g. having multiple sexual partners is often seen as a sign of male virility, and those who do not fulfil these expectations are ridiculed.Citation8 Citation9 Citation10 Citation11 While it is true that women also experience pressure from their peers and men, evidence in India suggests that women by and large do not have multiple sexual partners as much as men do.Citation12

It has also been shown that gender role differentials widen during adolescenceCitation13Citation14, as boys enjoy privileges reserved for men such as autonomy, mobility and opportunity while girls find their mobility and education restricted.Citation15 Differing social advantages have direct and indirect effects on reproductive behaviour and future health and well-being.Citation16Citation17 Gender-based violence, sexual abuse of women and homophobia in expressions of masculinity are some of the negative consequences.Citation17

Although there is increased awareness of the role of inequitable gender norms, few intervention studies have attempted to influence these norms or measure any changes that occur. Yet efforts to promote male involvement in family planning show that men need information and awareness to be able to take appropriate decisions.Citation18 Citation19 Citation20 Horizons, implemented by the Population Council, along with CORO for Literacy, an Indian NGO, and Instituto PROMUNDO, a Brazilian NGO, developed, adapted and implemented an intervention for young men to promote gender equity as part of an HIV prevention programme. This paper highlights the formative research findings on how masculinity and gender norms are expressed by young men, the intervention and the changes in attitude as a result of it.

Methodology

Formative research was conducted in low-income communities in Mumbai, India, on the links between gender and masculinity, sexuality and health risks. First, a mapping of the communities was conducted to identify possible intervention strategies and key issues to be addressed. It was done with the help of key informants and informal discussions with parents and other community members. Key informants also included young men who shared their opinions and information about the situation and lifestyles of youth and slightly older men who wielded significant influence over the younger ones. Nine peer leaders from the communities who were working with CORO for Literacy and who participated in the formative research, were willing to take a leading role in the intervention. These young men reflected voices of resistance in terms of their opposition to the patriarchal system and were clearly “positively deviant” within their own community. They underwent a two-week training programme to strengthen their gender and HIV-related knowledge and facilitation skills and were trained in qualitative methods of data collection. Under the guidance of the researchers, they conducted a total of 51 key informant and in-depth interviews with young men aged 16–24. In addition, peer leaders conducted focus group discussions with NGO leaders (one), political and religious leaders (one), and young women (two) from the same communities.

Intervention activities for young men were then developed and piloted. The same peer leaders who conducted the qualitative research were trained to facilitate group education sessions. They recruited 126 young men to participate in four groups of 30–35 each over a six-month period. Volunteers were sought from existing youth groups in the community, vocational training centres, political, cultural and religious youth groups, youth on the street, and through word of mouth and the peer leaders’ friends.

The intervention team monitored attendance at sessions and kept track of the themes discussed during activities. An independent study team pre-and post-intervention surveys with most of the young men (n=107 and n=92, respectively). The post-intervention survey was two months after the last group session. Qualitative interviews were conducted with a subset of 16 young men after selected sessions and with those who had dropped out of the intervention (n=11), as well as with the four peer leaders who facilitated the sessions. Observations of selected activities by the research team also took place.

Attitudes toward gender norms were quantitatively measured in the surveys using the 24-item Gender Equitable Men (GEM) Scale, developed in Brazil,Citation21 which consists of a list of statements about men’s and women’s roles related to domestic life and childcare, sexuality and sexual relationships, reproductive health and disease prevention, intimate partner violence as well as attitudes towards homosexuality and close relationships with other men. Respondents were asked to read each statement carefully and indicate, using a three-point scale, whether they strongly agreed, partially agreed or disagreed with the statements. GEM Scale items were pre-tested and discussed with a sample of young men from low-income communities in Mumbai (n=65) to ensure that the statements were relevant and clear in the Indian context. At baseline, the GEM Scale was highly internally consistent (alpha=.86). Other key outcomes addressed in the surveys included HIV knowledge, sexual harassment, physical and sexual violence, condom use and number of sexual partners.

Socio-demographic characteristics of participants

The 107 young men who completed the pre-intervention questionnaire represented both Muslim and Hindu communities. They were largely migrants from north India, Maharashtra and South India. Their mean age was 21 (range 18–29); 72% were single, 19% had girlfriends and 9% were married; 56% had completed 11 years or more of formal education. Most of them earned less than Rs. 2000 (US$45) per month. All the young men lived with their parental families, who had low to medium, often irregular, income.

Findings

Normative concepts of masculinity

When asked about masculinity, young men described physical and social attributes of a real man (asli mard in Hindi). How masculinity is understood and expressed by young men is presented in detail elsewhere.Citation22 Overall, a real man is someone who is handsome, strong, muscular and virile. These attributes are considered important because they help attract women and enhance men’s sexual prowess so that they can sexually satisfy women. Sexual potency is seen as an important way to establish superiority and control over women. A real man should not have baila (feminine mannerisms), which is considered characteristic of homosexual men. Some informants used demeaning terms to describe men who have sex with men.

Socially, a real man is someone who takes care of his children, wife, parents and siblings. Throughout the interviews, responsibility to family was the most frequently cited attribute of a real man and seen as a positive aspect of masculinity.

“He should earn well and look after his family.”

“He should be sincere and loyal to his wife.”

Being dominant was another quality associated with real men. Physical and verbal aggression against other men, either individually or in a group, were often highlighted as proof of masculinity. “Real men lead and win fights and quarrels.” But aggression to prove manhood was also directed at women – wives, girlfriends and acquaintances. Informants often referred to women as chhav, an object or item to be possessed by men. Sexually coercive behaviour was commonly used by men to demonstrate sexual power, including derogatory comments, whistling, jostling, touching and harassment in public places. Sexually coercive activities also included forced kissing and forced intercourse. Very often coercion was directed at women or girls who seemed to challenge masculinity.

“[The youth] follow women, tease them, stare at them. When they see a good-looking woman or a girl they call to her ‘What an item!”

“My friends challenged me. They said if you are a Real Man then engage that girl [to get her to have sex] within eight days.”

An ideal woman was defined as one who does not respond to men’s sexual advances and is therefore marriageable. In particular, women raising the idea of condom use or carrying condoms were seen negatively. “A woman who carries a condom and asks for a condom is corrupt.” Such girls are considered promiscuous and deserving of sexual harassment and coercion.

“If a boy teases a girl and the girl passes by without saying a word, then it shows that she is a good girl. If she retorts back then it means she is proving herself smart.”

Other behaviours encouraged by peers included drinking alcohol, smoking or using drugs.

“…during one of the festivals, all the boys were sitting together and had their bottle with them. They tried to force me to drink but I refused. So all the boys began teasing me: “You are a ‘gud’ (feminine boy). This put me off. I drank four glasses of raw liquor. It was so strong that I was unconscious for days.”

Prevailing attitudes towards condom use

Condom use did not figure prominently in the lifestyles of these young men. Sex with girls happened in a variety of situations, often in a hurry or characterised by coercion or force, with little thought given to using a condom.

“When somebody is sexually excited why would he spend time taking out a condom and putting it on his penis?”

Girlfriends and wives were not seen as at risk of spreading disease, and therefore condoms were never used with them, even though the young men themselves may have had multiple partners.

“….why should I use condoms during sexual relations with my own wife or girlfriend. It is not needed.”

Sex with other men, including with hijras (transgender people) was not considered to be risky either.

“During sex with hijras one does not need condom.”

An exception to condom use was with sex workers. There was an enormous amount of fear of AIDS among informants, therefore condom use was common with sex workers. In fact, there were reports of young men taking what they thought were extra precautions with sex workers.

“I used two condoms at a time (while having sex with a sex worker). By chance if one leaks then there can be another protection.”Footnote*

Yari-dosti: activities promoting gender equitable norms and behaviours

Based on these results and drawing on experiences addressing gender equity in other cultural contexts, a behaviour change intervention targeted at young men was developed and piloted. The intervention attempted to spur critical thinking about gender norms that promote risky behaviour and to create support for gender norms that promote caring and communication, tapping into alternative voices and images of young men. We defined a gender-equitable man as one who (1) supports relationships based on respect, equality and intimacy rather than sexual conquest, (2) is or seeks to be involved as a domestic partner and father, both in terms of childcare and household activities, (3) assumes or shares with his partner(s) the responsibility for reproductive health and disease prevention, (4) does not practice violence and opposes intimate partner violence, and (5) opposes homophobia.

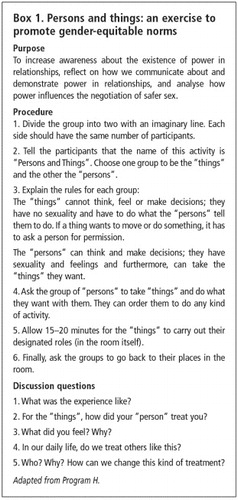

The intervention was named Yari-dosti, which means friendship or bonding among men in Hindi. It was adapted from Program H, an intervention designed for young men by Instituto PROMUNDO and partners in Brazil.Footnote† During a week-long workshop, followed by two months of community consultations, the team adapted 20 group exercises from Program H, including changing characters, story lines and examples, and in a few cases the format and content of the exercises. The intervention started with an intensive week of group education activities, facilitated by both peer leaders and gender specialists, followed by 2–3 hour sessions every week, led by the peer leaders, over the six months. Among the main themes covered in the exercises were STI/HIV risk and prevention, including condom use negotiation; partner, family and community violence; gender and sexuality; and reproductive health. The group educational activities were based on participatory methods of learning with extensive use of role plays, games and exercises that engaged young men in discussion, debate and critical thinking. See Box 1 for an exercise that aims to promote gender sensitivity.

Responses to the educational sessions

Almost all the young men recruited consistently participated in the activities, and were greatly interested in the topics. It was often their first opportunity to discuss these issues openly, and they particularly liked talking about them with other men.

“The interactions with boys in the groups stunned me initially. I was all the while thinking that only I thought like this about women and other men. There are many who think like me… but we never get a chance to talk and share.”

Initially, they were most interested in factual biological information, e.g. about the body, sex and HIV, and these themes were what drew them to the sessions. Over time, they found the workshops on gender-related attitudes, partner violence and power dynamics between men and women engaging and eye-opening.

“The larger environment around us provides justification for violence and coercion. We see men beating their partners and wives, and there is a tendency to emulate them.”

When asked about the effects of participation, some of the young men said the sessions had changed their understanding of love, sexuality and masculinity. Others described changes in their personal behaviour and relationships.

“I was thinking earlier that condom use reduces sexual pleasure. Now I feel that those who think so have not understood what sexuality is. It’s not only penetrative sex but every part of our body that can give us sexual pleasure. Understanding between partners is the main thing.”

“After the session on erotic body, my views about sex have changed… I don’t think many of us in this community ever thought like this.”

“Boys ‘tease’ girls because they think it’s natural and rightful. I know. I used to be one of them.”

“I was about to divorce my wife due to misunderstandings. These sessions stopped me from doing that.”

Not all of the responses were positive, however. Some found it difficult to maintain new behaviours or experienced problems when they attempted to incorporate new perspectives into their daily lives, e.g. one young man who dropped out of the programme:

“I have lost intimacy with friends (because of the change in my attitudes)… Losing friends makes me unhappy.”

“In my relationship with my girlfriend the question, ‘Am I dominating?’, is always at the top of my mind now. This is very irritating sometimes. Admittedly, however, the quality of our relationship has improved.”

“What is the point in discussing these issues here in the class room… most boys and young men outside in the community don’t believe in all this…we need to bring them into the programme.”

Perspectives of the peer leaders

The peer leaders observed that a substantial majority of the young men went through a process of change over time, which began with denial that gender-related norms existed or could be linked to risk for both men and their partners. This transitioned to gradual acceptance that these norms existed and that change would be worthwhile, and then to exploring ways in which they and others could challenge these norms and behaviours. The peer leaders were also changed by the experience:

“The intervention sessions have helped me become a listening person, a responsible person and a thinking person. All these helped me to better my performance in relating with people and attending to their issues.”

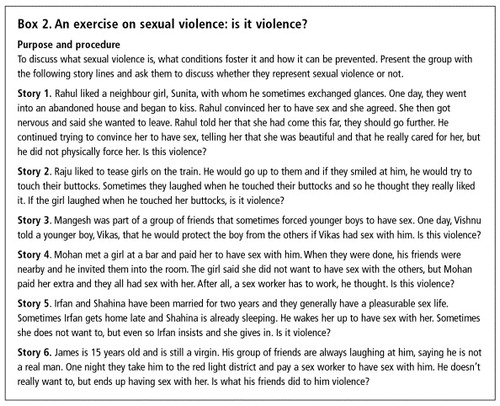

Some sessions resulted in heated discussions and debate. This was particularly evident in exercises that had participants role-playing stigmatised groups, including sex workers and people living with HIV, and exercises that discussed intimate partner violence, where conflict-management skills were needed. For an example of a controversial session, see Box 2.

Significant shifts in gender-related attitudes

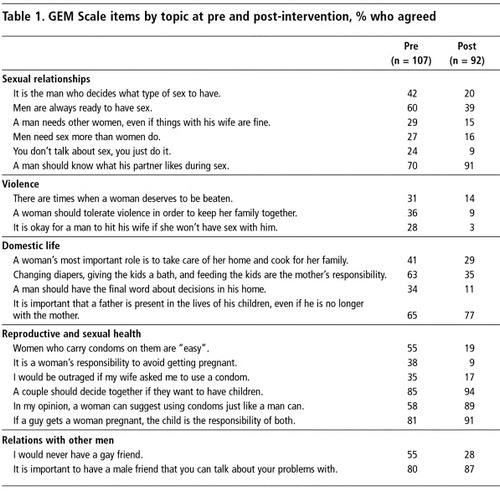

The survey findings reinforced many of the findings from the qualitative interviews and observations. At baseline, a substantial proportion supported many inequitable gender norms, but these attidues positively changed in the post-intervention survey, most reaching significance at p<.05 (Table 1). When the sample is restricted to the 92 young men who answered both the pre-and post-intervention survey, the results are similar.

At the same time, there was great support for some equitable gender norms both pre-and post-intervention. For example, that a couple should decide together if they want to have children. Thus, many young men held both equitable and inequitable gender beliefs simultaneously.

Discussion

The predominant view of masculinity and men’s roles in sexual and romantic relationships initially espoused by the young men before the intervention was one of entitlement and dominance. The gender-focused workshops attempted to promote positive norms such as responsibility and caring for one’s sexual partners, as well as respect for one’s partners and women in general. Qualitative and quantitative findings indicate that positive changes in attitudes towards gender, sexuality and intimate relationships are possible via participation in a gender-focused intervention, and that the pilot intervention was successful in engaging young men to critically discuss gender dynamics and norms.

Based on these findings, a larger evaluation of the intervention is currently in progress with over 1,000 young men in both Mumbai and rural settings in Uttar Pradesh. The intervention has also been broadened so that group education activities in some sites are combined with a community-based and gender-focused “lifestyle” social marketing campaign, to reinforce gender equity and HIV prevention messages. Preliminary findings are similar to those found in the pilot intervention, including an expressed need to reach out with gender-equitable messages to the community more widely. Young men are actively participating in the development and implementation of this campaign. With the slogan Soch sahi mard vahi (“Real” men have the “right” attitude), the campaign consists of street plays, posters, pamphlets, banners and a service and information booth.

Equally promising findings emerged in an evaluation of Program H in Brazil,Citation23 which included 780 young men aged 14–25 years. Participation in Program H led to significantly fewer gender-inequitable attitudes and behaviours among young men, including significantly increased condom use, fewer reported STI symptoms and development of close relationships with young women based on other interactions besides or in addition to sexual ones. Some female partners reported increased communication in their relationships and increased interest in their opinions on the part of their male partners.

Well-developed facilitation skills during both the Brazilian and Indian workshops were of key importance. Therefore, sufficient training on gender-related issues, on encouraging young men to speak about sensitive and often taboo subjects and on handling disagreements among participants is crucial.

Scaling up this type of intervention has its challenges, such as the need for a cadre of qualified and well-trained facilitators. It would require the training of trainers to work with a variety of groups, such as teachers and youth workers as well as peer leaders to work with young men. Yet, this type of intervention, with its critical discussions and reflections, can be adapted and implemented almost anywhere and is relatively inexpensive. Furthermore, the promising findings from this pilot indicate that addressing these issues in the Indian context is both relevant and important for gender relations and all the benefits arising from that for both young women and men. The authors would argue that openly discussing these topics should form part of universal sexuality education in India and elsewhere.

Acknowledgements

The research was funded by USAID under a Cooperative Agreement with the Horizons Program/Population Council, and the John D and Catherine T MacArthur Foundation. The authors would like to acknowledge the contributions of Mahendra Rokade, Vilas Sarmalkar and the CORO team in the adaptation and implementation of the pilot intervention. Many thanks to Ellen Weiss for critical review and editing of the manuscript, and to Jennifer Redner for assistance proofreading and preparing the manuscript.

Notes

* There is no evidence that wearing two condoms is more protective.

† For more information about both the Yari-dosti intervention and Program H: Young Men and HIV Prevention, see Horizons Report, December 2004. At: <www.popcouncil.org/horizons/newsletter/horizons(9).html>.

References

- National AIDS Control Organization. HIV/AIDS Epidemiological Surveillance and Estimation Report for the year 2005. New Delhi, April 2006.

- National AIDS Control Organisation 2005. At: <http://nacoonline.org/vasco/indianscene/overv.htm. > and <http://www.nacoonline.org/facts_reportjan.htm. >. Accessed 13 March 2006.

- PJ Pelto, A Joshi, R Verma. Development of sexuality and sexual behaviour among Indian males: implications for the reproductive health program. Paper prepared for “Enhancing the roles and responsibilities of men in sexual and reproductive health”. 1999; Population Council: New Delhi.

- RK Verma, VS Mahendra. Construction of masculinity in India: a gender and sexual health perspective. Indian Journal of Family Welfare. 50(Special issue): 2004; 71–78.

- E Weiss, D Whelan, G Rao Gupta. Gender, sexuality and HIV: making a difference in the lives of young women in developing countries. Sexual Relationship Therapy. 15(3): 2000; 233–245.

- P Mane, P Aggleton. Gender and HIV/AIDS: what do men have to do with it?. Current Sociology. 49(4): 2001; 23–37.

- G Barker. What about Boys? A Review and Analysis of International Literature on the Health and Developmental Needs of Adolescent Boys. 2000; World Health Organization: Geneva.

- RK Verma, H Lhungdim. Sexuality and sexual behaviors in rural India: a five-state study. R Verma, P Pelto, A Joshi. Sexuality in the Time of AIDS: Contemporary Perspectives from Communities in India. 2003; Sage: New Delhi, 432.

- P Aggleton, K Rivers. Behavioral interventions for adolescents. L Gibney, R DiClemente, S Vermund. Preventing HIV Infection in Developing Countries. 1998; Plenum Publications: New York.

- E Zelaya, FM Marin, J Garcia. Gender and social differences in adolescent sexuality and reproduction in Nicaragua. Journal of Adolescent Health. 21(1): 1997; 39–46.

- S Berglund, J Liljestrand, FDM Marin. The background of adolescent pregnancies in Nicaragua: a qualitative approach. Social Science and Medicine. 44(1): 1997; 1–12.

- S Jejeebhoy, MP Sebastian. Young people’s sexual and reproductive health. S Jejeebhoy. Looking Back, Looking Forward: A Profile of Sexual and Reproductive Health in India. 2004; Population Council: New Delhi, 139–168.

- L Devasia, VV Devasia. Girl Child in India. 1991; Ashish Publishing House: New Delhi.

- J Bruce, C Lloyd, A Leonard. Families in Focus: New Perspectives on Mothers, Fathers, and Children. 1995; Population Council: New York.

- M Greene. Watering the neighbours’ garden: investing in adolescent girls in India. South and East Asia Regional Working Paper No.7. 1997; Population Council: New Delhi.

- B Mensch, J Bruce, M Greene. The Uncharted Passage: Girls’ Adolescence in the Developing World. 1998; Population Council: New York.

- M Berer. Men [Editorial]. Reproductive Health Matters. 4(7): 1996; 7–10.

- J Seex. Making space for young men in family planning clinics. Reproductive Health Matters. 4(7): 1996; 111–114.

- K Ringheim. Whither methods for men? Emerging gender issues in contraception. Reproductive Health Matters. 4(7): 1996; 79–89.

- L Hulton, J Falkingham. Male contraceptive knowledge and practice: what do we know?. Reproductive Health Matters. 4(7): 1996; 90–100.

- Pulerwitz J, Barker G. Measuring attitudes towards gender norms among young men in Brazil: development and psychometric evaluation of the GEM Scale. Men & Masculinities (Forthcoming).

- RK Verma, J Pulerwitz, VS Mahendra. From research to action – addressing masculinity as a strategy to reduce risk behaviour among young men in India. Indian Journal of Social Work. 24(Dec): 2004; 434–454.

- J Pulerwitz, J Barker, M Segundo. Promoting more gender-equitable norms and behaviors among young men as an HIV/AIDS prevention strategy. Horizons Final Report. 2006; Population Council: Washington, DC.