Abstract

Using qualitative and survey data in a rural and an urban slum setting in Pune district, India, this paper describes patterns of pre-marital romantic partnerships among young people aged 15-24, in spite of norms that discourage opposite-sex interaction before marriage. 25–40% of young men and 14–17% of young women reported opposite-sex friends. Most young people devised strategies to interact with others, largely from the same neighbourhood. There were wide gender differences with regard to making or receiving romantic proposals, having a romantic partner and experiencing hand-holding, kissing and sexual relations. For those who engaged in sexual relations, the time from the onset of the partnership to having sexual relations was short. Sex most often took place without protection or communication, and for a disturbing minority of young women only after persuasion or without consent. Among those who were unmarried, a large percentage had expected to marry their romantic partner, but for a third of young women and half of young men the relationship had been discontinued. Partnership formation often leads to physical intimacy, but intimacy should be wanted, informed and safe. Findings call for programmes that inform youth in non-threatening, non-judgmental and confidential ways, respect their sexual rights and equip them to make safe choices and negotiate wanted outcomes.

Résumé

Fondé sur des données qualitatives et d’enquêtes dans des bidonvilles ruraux et urbains du district de Pune, Inde, cet article décrit les relations prémaritales chez des jeunes de 15–24 ans, même si les rapports avec le sexe opposé sont découragés avant le mariage. 25-40% des jeunes hommes et 14-17% des jeunes femmes ont indiqué avoir des amis du sexe opposé. La plupart des jeunes avaient conçu des stratégies pour avoir des relations, principalement avec des habitants du même quartier. Faire ou recevoir des propositions amoureuses, sortir avec un garçon ou une fille, lui tenir la main, l’embrasser ou avoir des relations sexuelles étaient des expériences très différentes selon les sexes. Pour ceux qui avaient des relations sexuelles, peu de temps s’écoulait entre le début de la relation et les premiers rapports sexuels. Ces rapports avaient le plus souvent lieu sans protection ni communication, et pour une minorité inquiétante de jeunes femmes, seulement moyennant persuasion ou sans consentement. Un fort pourcentage de célibataires avaient pensé épouser leur partenaire, mais la relation avait été rompue pour un tiers des jeunes femmes et la moitié des jeunes hommes. Une relation conduit souvent à l’intimité physique, qui doit être voulue et sans risque. Les jeunes nécessitent des programmes qui les informent de manière confidentielle, non menaçante et sans les juger, dans le respect de leurs droits sexuels et en leur permettant de faire des choix sûrs et de négocier des résultats escomptés.

Resumen

Utilizando datos cualitativos y de encuestas en zonas rurales y en un barrio bajo urbano del distrito de Pune, en la India, este artículo describe los patrones de las relaciones románticas prematrimoniales entre los jóvenes de 15–24 años de edad, pese a las normas que frenan la interacción entre sexos opuestos antes del matrimonio. Entre el 25% y el 40% de los jóvenes y el 14% y el 17% de las jóvenes informaron tener amigas/os del sexo opuesto. La mayoría de las personas jóvenes idearon estrategias para interactuar con otros, principalmente del mismo barrio. Se observaron amplias diferencias de género con respecto al plantear o recibir propuestas románticas, tener una pareja romántica y experimentar tomarse de la mano, besarse y tener relaciones sexuales. Para aquéllos que tuvieron relaciones sexuales, el tiempo desde el inicio de la relación a la primera relación sexual fue corto. Por lo general, las relaciones sexuales ocurrían sin protección o comunicación, y para una alarmante minoría de mujeres jóvenes, sólo después de ser persuadidas o sin su consentimiento. Entre aquellas personas solteras, un gran porcentaje esperaba casarse con su pareja romántica, pero para la tercera parte de las jóvenes y la mitad de los jóvenes la relación había terminado. La formación de parejas a menudo conduce a la intimidad física, pero ésta debe ser deseada, informada y segura. Los resultados indican que deben crearse programas para informar a la juventud sin amenazas, sin prejuicios y de manera confidencial, respetar sus derechos sexuales y equiparla para tomar decisiones seguras y negociar los resultados deseados.

Young people in India today are at a crossroads, confronted by opposing forces. A larger proportion than ever before are in schools and colleges, healthier and better nourished, have access to wide-ranging media and the benefits of new technology, and are exposed to new ideas about their roles and rights. At the same time, they face traditional age-and sex-stratified norms that espouse gender double standards and discourage the formation of romantic partnerships or even friendships among the unmarried and the selection of their own spouse. Arranged marriages remain the norm and those who pursue pre-marital relationships not only run the risk of bringing dishonour to the family but also reduce their chances of a good marriage. The hint of a pre-marital relationship can, moreover, hasten marriage for young women to a man not of their choice.

Evidence on the nature of pre-marital relationships in India is sparse and comes from small and unrepresentative studies. These suggest that despite sanctions and strict controls over young women’s sexuality, partnerships are formed, while sexual relations are experienced among 15-30% of young men and about 10% of young women.Citation1 Citation2 Citation3 Citation4 Sons have more freedom than daughters, are encouraged to attend school, seek employment and socialise with peers outside the home, but close relationships with girls are discouraged. Opposite sex friendships, sex and reproduction are rarely discussed within families as many parents believe this would imply approval of sexual activity.Citation4 Citation5 Citation6 In these circumstances, it is not surprising that young people who do develop partnerships with the opposite sex do so clandestinely, and rarely tell their families.Citation4Citation7 For young women, these experiences may or may not be consensual; where consensual, the partner is predominantly a boyfriend.Citation8 In contrast, young men experience sex with a range of partners, including girlfriends, sex workers and older married women and men. Homosexually active men may have sexual relations with women as well.Citation9, Citation10

Policies and programmes in India, like parents and communities, do not provide sexual and reproductive health information, counselling or services to unmarried youth. Indeed, there is little recognition at the programme level of young people’s sexual rights, or their right to information and services. There are few public sector efforts to institutionalise sexuality education or promote gender equitable relationships among the young.

This study aimed to assess the extent to which young women and men aged 15–24 in a rural and an urban slum setting in India have engaged in pre-marital romantic partnerships, the extent of physical intimacy experienced in these partnerships and gender differences in these patterns, and for those whose partnerships involved sexual relations, the nature of those relationships.

Setting and methodology

The study was conducted in 2004–2005 in Pune district, Maharashtra, which is close to the state capital, Mumbai. Compared to other states in India, socio-economic indicators in Maharashtra are relatively high, and Pune is one of the most economically developed districts.Citation11 HIV prevalence is also high, including among youth.Citation12 Youth in Pune district are assumed to have greater access to education, employment opportunities, modern consumer goods, new ideas and modern lifestyles than those in most other districts of the state.Citation13 Within the district, study sites were purposively selected that had a strong NGO presence. The rural site covers a population of roughly 100,000 from 90 villages in one sub-district; the urban site is a slum in Pune city, housing one-fifth of slum residents.

The study comprised three phases: a pre-survey qualitative phase that provided insight into youth perspectives and experiences, a survey and in-depth interviews with selected respondents reporting romantic partnerships or sexual relations. An initial house-listing exercise identified all households containing youth aged 15–24 in each site. Unmarried and married women and men were randomly selected from these lists. In cases where both a woman and her husband were eligible, only one person was interviewed. Where a household contained more than one eligible respondent in any of the four categories, only one was selected randomly. No replacement was permitted. Refusal rates tended to be lower than 5% for all groups. Married men proved more difficult to recruit largely due to work-related mobility and long working hours followed by alcohol use, curtailing opportunities for interview.

The survey instrument drew on insights from the pre-survey qualitative phase and other instruments relating to youth behaviours.Citation14 Citation15 Citation16 Citation17 Citation18 Citation19 It explored in detail romantic partnerships in which young people engage. All respondents answered the same questions; those who were married were asked to recall their pre-marital partnerships. We asked not only about sexual experiences in romantic partnerships but also relations without consent, and with sex workers and older women and men. Significant efforts were made to ensure privacy for the interview. Reports of pre-marital sexual experience were also provided anonymously in a sealed envelope.Citation20

This paper focuses on young people’s romantic partnerships with an opposite-sex partner. Although we also tried to capture same-sex romantic partnerships, experiences were reported by fewer than 0.5% of respondents and are therefore not discussed here. Weighted means and percentages are presented that reflect the marital status distribution of youth aged 15–24 in rural and urban Pune district respectively, drawn from the 2001 census.Citation12 T-tests are presented of the significance of differences between reports of rural and urban men, and rural and urban women.

Profile of respondents

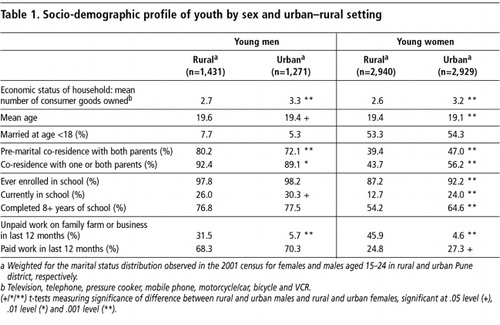

Table 1 shows the socio-demographic characteristics of respondents. While all respondents were aged around 19 years, other socio-demographic characteristics varied widely by sex and sometimes residence. Of note are wide gender differences in marriage age and significant differences in schooling profiles and current economic activity. Young men were considerably more likely than young women to be wage-earners. Likewise, rural youth were significantly more likely than urban youth to be involved in unpaid work, usually in a family farm or business.

Meeting and making and receiving proposals

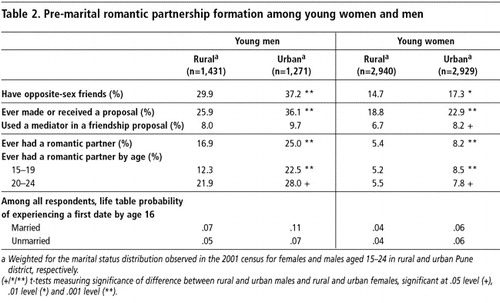

Despite perceptions to the contrary, interactions between young women and men in both rural and urban settings were not rare. 25–40% of young men reported opposite-sex friends and 14–17% of young women (Table 2).

During the pre-survey qualitative phase, it became clear that young people employed a distinct set of terms to define romantic partnerships; for example, “to propose” meant an offer of romantic partnership, and “loveship” described romantic partnerships, including or excluding sexual relations, with or without marriage in mind. “Romantic partnerships” were what might be called a dating or girlfriend–boyfriend relationship in other contexts. Narratives highlighted young people’s familiarity with these behaviours as well as their experiences of initiating or receiving these proposals.

“There are mixed groups in 12th standard… Boys in the group have proposed to girls in the group for loveship.” (Focus group discussion, unmarried urban females)

“She starts giving ‘line’ [signs of liking the boy]… Then they smile, talk. Then he goes up directly and proposes loveship.” (Focus group discussion, unmarried urban males)

Significantly more urban than rural young men reported either receiving or making a proposal of partnership (Table 2). In contrast, few young women reported receiving or making such a proposal. The difference between the reports of young women and young men receiving proposals may be attributed to the reluctance of young women to disclose such information, on the one hand, and the tendency of young men to exaggerate their attractiveness to girls, on the other. It may also reflect a genuine difference in terms of opportunities for forming partnerships in that young men may have contacts in a larger geographic area than young women.

In-depth interviews suggest that proposals are made in several ways. While many young men declare their affection directly, several unmarried young women reported that the boy had handed her a letter declaring his love and delivering a “proposal”. For example:

“The next day I told her directly that I liked her, at that time she was alone. She did not say anything. In this way, over one month I proposed to her forty-five times…I would tell her whenever she was alone…After a month, when I met her alone and proposed, she said yes.” (In-depth interview, unmarried urban male, age 17)

“He gave me a letter… I took the letter but I didn’t know how to react… He wrote, ‘I like you a lot. I love you very much and I am waiting for a positive answer. If you say no I will feel very bad.’ I did not reply. After a month on my birthday he sent me a greeting [card]. Then I said yes. I also wrote a letter to him.” (In-depth interview, unmarried rural female, age 18)

Given the clandestine nature of partnership formation, proposals were often made through intermediaries. A focus group discussion with unmarried urban girls reported that other girls may help a boy convey his interest to a girl, perhaps by phoning or sending her chits or letters on his behalf, or trying to convince her to be interested in him. Survey findings corroborated this pattern. About a quarter to a third of young men and women who reported making or receiving a proposal also reported an intermediary (Table 2). Post-survey, in-depth interviews highlighted that intermediaries were typically friends, younger siblings or other children in the community.

“I looked after 2 or 3 small boys… gave them chocolates… I would send chits through them.” (In-depth interview, married urban male, age 21)

“Yes, he proposed to me for love. He told my friend to tell me that he liked me a lot, and to ask me if I would love him.” (In-depth interview, unmarried rural female, age 15)

Forming a romantic partnership

About 17% of rural young men and significantly more urban young men (25%) reported having a romantic partner, while about 5–8% of young women reported such an experience, again more from urban than rural areas (Table 2).

In order to examine ages at partnership formation, we explored through life table analysis, the probability of having a first date by age 16 among all respondents. Kaplan-Meier estimates, presented in Table 2, suggest wide gender differences: 5–11% of young men had an opposite-sex romantic partner by age 16, compared to 4–6% of young women. Of note also is the finding that those who were unmarried were about as likely as those married to report a pre-marital partnership. Thus, our concern that unmarried youth might be less willing to disclose partnerships to avoid jeopardising their marriage prospects was unfounded.

Characteristics of pre-marital partnerships

Respondents who reported one or more opposite-sex romantic partners were asked a series of questions about the characteristics of partners, age at first relationship and parental and peer awareness. In-depth interviews with survey respondents reporting pre-marital partnerships probed further into the nature and progress of these partnerships.

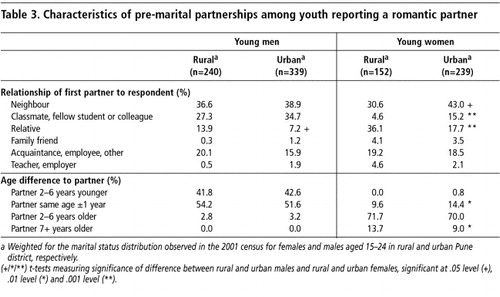

A range of types of partners was reported (Table 3). They were largely from the same neighbourhood. Young men were significantly more likely than young women to report a fellow student or colleague as their first partner. 16–20% of all respondents reported that their first partner was an acquaintance, usually someone they met at a bus stop, on the way to college or work or at a wedding or other function, or a colleague. Rural young women were significantly more likely than urban young women to report a relative as their first partner, and conversely significantly less likely to report a classmate or fellow student. This finding reflects the extent to which rural young women’s lack of mobility and opportunity limited their access to young men outside the family or neighbourhood, both in comparison to their urban counterparts and young men. Young women were typically younger than their male partners, with over 80% reporting that the partner was at least two years older than them.

Gender differences were evident as regards number of partners; while hardly any young women (under 5%) who had had a romantic partner reported more than one partner, about 25% of young men, irrespective of residence, reported that they had had more than one romantic partner (data not shown).

Parental and peer awareness of the partnership

Textual and survey data repeatedly highlighted young people’s reluctance to confide in parents about a partnership, but a greater willingness to confide in their peers.Citation6, Citation20 In several focus group discussions and in-depth interviews, young people reported that they feared their parents’ disapproval:

“If we start a friendship with a boy, if he meets us somewhere and if our parents see us talking then something might come to their minds. So we are scared and we wonder whether we should have friendships with boys… Some parents are really very strict. They don’t like us talking with boys, they also don’t like friendships with boys… If we have friendships behind our parents’ backs they don’t like it.” (Focus group discussion, unmarried urban females)

“Who would take on the tension [of telling parents of the friendship]? My parents would have beaten me. No one knew in my house or in her house.” (In-depth interview, unmarried urban male, age 19)

However, while efforts were made to pursue partnerships without parents’ knowledge, in many instances parents did become aware of their children’s partnerships (not shown in tabular form). Patterns varied across groups: young men were more successful in hiding a relationship from their parents than young women, perhaps because their greater mobility enables them to avoid arousing parental suspicion. Likewise, rural youth appeared to be significantly more successful than urban youth in concealing a partnership from their parents.

Young people were clearly freer about their partnerships with their peers than with their parents. Some 80% or more of all respondents who experienced partnerships reported that their peers were aware of them, with little variation in peer awareness by sex or rural–urban residence, unlike in the case of parental awareness. In-depth interviews similarly reflect this openness.

“My friends knew about it. My close friend… knew about it as I would tell him everything; he too would tell me everything about his girlfriend.” (In-depth interview, unmarried urban male, age 19)

Meeting sites

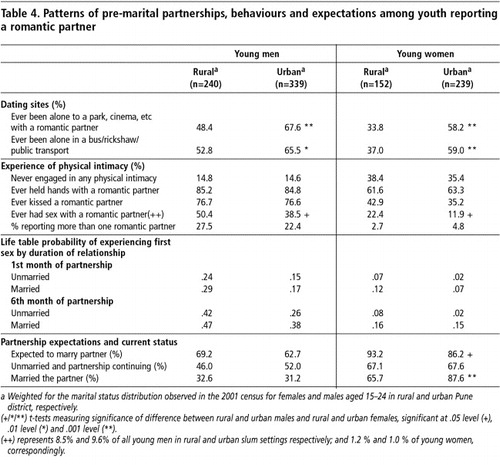

The study explored young people’s opportunities to meet in private, intimate behaviours experienced from handholding to sexual relations, expectations of the partnership and current status. Although social norms dictate that unmarried young women and men must not mix or meet in public or private, and prohibit physical intimacy before marriage, young couples do find opportunities to meet privately and to engage in physical intimacy (Table 4).

Meeting in a park, temple, bazaar, cinema, tourist spot and on public transport (bus, rickshaw) were reported in the pre-survey qualitative phase as typical of places where romantic partners met privately. But not all of those reporting a romantic partnership in the survey met alone in any of these locations (Table 4). Significantly more young men reporting a partnership had met their partners in one of these sites compared to young women. Urban youth likewise were significantly more likely than rural youth to have met in any of these locations. The qualitative findings suggest that meetings tended to be sporadic and opportunistic and frequently took place at the home of the girl or boy when other household members were absent.

Experience of physical intimacy

Respondents were asked whether they had engaged in a range of intimate behaviours, from handholding to kissing on the lips to sexual relations with the romantic partner. As shown elsewhere,Citation21 wide gender differences in reporting were evident. Some 15% of young men and 35% of urban and 38% of rural young women who reported a partnership reported no physical intimacy at all (Table 4).

Young women were not only far less likely than young men to report any of these experiences, but there is also a steady decline in the proportion reporting these experiences with increasing forms of intimacy, with some 62–63% of young women reporting hand-holding, 35–43% reporting kissing and 12–22% reporting sexual relations. The decline among young men is not as steep: hand-holding was reported by 85%, kissing by 76–77% and sexual relations by 39% of young urban men and 50% of young rural men.

Narratives suggest a progression from establishing the romantic partnership to engaging in physical intimacy, including sexual intercourse for some:

“[We started a romantic partnership] after 20 days. No [I was not alone]. My friends were also there. After two months I met him alone. We chatted for some time… We used to talk about my friends… [smiles]. Yes, he held my hand and kissed me also… After one or one and a half months [we had sex].” (In-depth interview, unmarried urban female, age 20)

Although fewer rural than urban respondents reported a romantic partnership, young rural men and women were more likely to report sexual relations with a romantic partner than urban residents, which we speculate may be associated with greater opportunities for privacy.

As a percentage of the total respondents (including those who did not report a romantic partnership), youth who had engaged in sexual relations with a romantic partner represented 9–10% of the young men and about 1% of the young women; there were virtually no differences by residence status. While these figures fall on the lower side of reported rates of pre-marital sexual experiences in a recent review of the literature,Citation3 our findings exclude relations that may have been forced, casual or that took place with a same-sex partner, sex worker or older woman; moreover, ours was a community-based study while most studies focus on school-or college-going youth, somewhat older youth or purposively selected groups of youth.

Time from partnership formation to first sex

Among youth reporting a romantic partner, we explored through life table analysis, the probability of reporting first sex by duration of the relationship, using Kaplan-Meier estimates of probabilities of engaging in first sex within one and six months of starting a partnership (Table 4). Probabilities suggest wide gender differences: among young men, 25% or more of those in rural settings and about one seventh of those in urban settings reported engaging in sexual relations within the first month of the partnership; this increased to between 25% (unmarried urban young men) and almost 50% (married rural young men) within six months of initiating a partnership. Among young women, 2–12% engaged in sexual relations with a romantic partner within a month of initiating the partnership and 2–16% within six months.

Expectations of marriage and current status

All respondents who reported a romantic partner were asked whether, in the course of the partnership, they had expected to marry their partner. While the majority in each group reported that they had expected to marry the person, young women were systematically more likely than young men to expect this (Table 4).

In in-depth interviews, while the majority of young men also reported a desire to marry their romantic partner, several had had no such intention.

“She wanted to get married to me but I did not want to marry her… My family would have shouted at me and our financial situation was not good.” (In-depth interview, unmarried rural male, age 17)

“No, not at all [did I want to marry her]. For time-pass I got friendly with her.” (In-depth interview, unmarried urban male, age 19)

“I had sex with her, but I did not like her like that [lasting relationship]. No. At that time I could not control myself that’s why I did it… I did not like her much. It was not possible for me to accept her as my wife.” (In-depth interview, unmarried urban male, age 20)

Expectations were not always fulfilled. Among those who were currently unmarried, despite the large percentage who had expected to marry their romantic partner, the partnership had been discontinued for about 33% of young women and 50% of young men. Likewise, among currently married youth, only 33% of young men had married a romantic partner, while considerably more young women (and significantly more urban than rural ones) reported marrying a romantic partner.

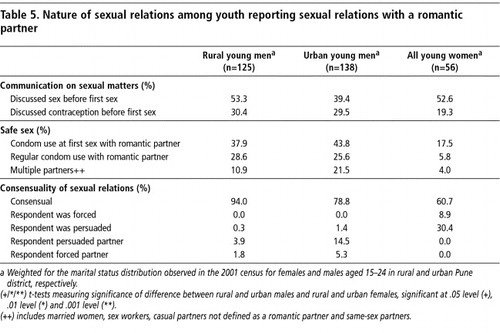

Communication about sexual relations

Table 5 presents evidence on the extent to which young people who engaged in sex in a romantic partnership communicated about sexual and contraceptive matters prior to engaging in sex, their use of contraception at first sex and thereafter, multiple partner relations, and the extent to which first sex was consensual. Numbers are particularly small among young women and we have therefore combined data for groups of young women. These findings reflect the extent to which sexual relationships among young people may involve considerable risk.

Limited communication on sexual matters was found. Instead, sex appeared to be undertaken spontaneously, without prior communication, or whether and what type of protection to use (Table 5). At best, only about half of those sexually active reported discussing sex. Far fewer discussed contraception with their partners prior to first sex. In-depth interviews suggest that in many cases there was no discussion, and where discussion had taken place, it did not appear to be well-informed. Often, communication consisted of the young man convincing the young woman to have sex, without her participating actively in the discussion.

Condom use and multiple partners

Condom use was far from universal (Table 5). Among young men, condoms were used by 38% of rural and 44% of urban young men at first sex; just over 25%, irrespective of residence, reported regular condom use with a romantic partner(s). Fewer young women reported condom use (pre-marital use of any contraceptive method was rare too; only six young married women reported using oral contraceptives and two married men reported withdrawal). In-depth interviews showed that while sexually experienced young men were familiar with condoms and had indeed used condoms, they were only rarely used at first sex, mainly due to lack of awareness and the unexpected or unplanned nature of first sex.

Aside from sex with a romantic partner, all survey respondents were also asked if they had ever experienced sexual relations with same-sex partners, married women, sex workers (for young men) and casual partners who they did not define as romantic partners, or if they had been the victims or perpetrators of forced sex, or whether they had exchanged sex for a favour. Among youth who had experienced sexual relations with a romantic partner, 11% and 22% of young men from rural and urban settings, respectively, had also engaged in sexual relations with one or more of the above categories of partners. Among young women who had experienced sexual relations with a romantic partner, in contrast, only 4% reported such experiences.

Consensuality of sexual experiences with a romantic partner

When asked whether first sex with any partner was forced, persuaded or consensual, the majority said it was consensual, again with marked gender differences. Young women were far less likely than young men to report that sex was consensual (Table 5). While numbers are small, 9% of young women reported that they had been forced and 30% that they had been persuaded, i.e. refused at first but then agreed, to have sex the first time with at least one partner. In contrast, 2% of young men from rural and 5% from urban settings admitted that they had forced their romantic partner to engage in sex the first time and 4% and 15%, respectively, that they had persuaded her. Some women acquiesced fearing that refusing would hurt their chances of marrying their partner. Most young women did not perceive these incidents as force or pressure.

“I shouted when he began to remove my clothes. He put his hand over my mouth and told me not to shout. He said that my voice should not be heard outside the door. I kept quiet as I was scared. Then he slowly removed my clothes and started kissing me. He lay down near me and started caressing me on my back and face. Then he put it inside twice.” (In-depth interview, unmarried urban female, age 19)

“Once he called me to the hills and told me to come to meet him… I went to meet him… and told him that I did not like all this and not to be after me. He made me sit down and caught hold of me tightly and told me that he would not let go of me… He kissed me on the lips, made me lie on the ground and then had sex with me. I could not do anything because he had caught hold of me tightly. My hands started to pain… It was against my wish. Then I had a lot of problems. I got a swelling there, I was bleeding and for three days I had a lot of pain. It was against my will. (In-depth interview, unmarried rural female, age 15)

“Initially I said no. But later I agreed… When I said no, he felt bad. Then he said that as we love each other, it is ok if we do it.” (In-depth interview, unmarried rural female, age 15)

“He told me that he wanted our child. Then I realised what he wanted. First I said no. He made a face, and I felt bad. Then I agreed. I did not want to hurt him.” (In-depth interview, unmarried urban female, age 18)

“I told her that if she really loved me then she should have [sex] with me at least once.” (In-depth interview, unmarried rural male, age 20)

“He told me that we should have sexual relations. I told him that I was not willing to before marriage. I was not ready. I thought that after I said ‘no’ he must have felt hurt… I did not want to hurt him…He wanted to marry me, he wouldn’t have got married then [if I refused sex]. I loved him a lot.” (In-depth interview, rural unmarried female, age 16)

Summary and conclusions

These findings confirm that even in this seemingly traditional setting, opportunities exist for the formation of pre-marital partnerships, and despite supervision by parents, young people do devise strategies to meet and communicate with members of the opposite sex and form partnerships.

Patterns of pre-marital relations suggest a clear progression in the courting experience, from making or receiving a proposal, to having an opposite-sex partner, to physical intimacy and sexual experience with that partner. There is a steady drop in the percentages of young people reporting more intimate behaviours. But among those who do initiate sexual relations, first sex occurs within a month of partnership formation for a significant minority.

Gender differences were considerable. While a similar percentage of young women and men had made or received a proposal of friendship, far more men than women had ever engaged in a romantic partnership, physical intimacy or sex with a romantic partner or someone else. Moreover, notable disparities in expectations of a longer-term commitment emerged that show young women to be at a distinct disadvantage in partnerships. Partner communication and negotiation about sex were rare, and because sex occurred spontaneously it was unprotected for many. For a disturbing minority of young women who had engaged in sexual relations with a romantic partner, sex was not consensual.

Finally, we acknowledge the limitations of our study. In this traditional setting governed by pervasive norms inhibiting any friendship with the opposite sex among young people – whether platonic, romantic or sexual – youth were unwilling to disclose romantic partnerships, notwithstanding the rapport between the study team and respondents. Under-reporting therefore cannot be ruled out.

It is fair to assume that opportunities will increasingly present themselves for social interaction and partnership formation between young women and men. Declining age at puberty combined with an increase in age at marriage create a growing window of opportunity in which to engage in sexual relations. Likewise, given trends in schooling levels, economic activity and media exposure, we can infer that young people will remain longer in school, become increasingly engaged in paid work and have greater access to new ideas, social mixing and partnership formation.

Our findings highlight that partnership formation usually leads to some form of physical intimacy. Hence, it is critical that policies and programmes for youth work towards ensuring that young women and men are fully informed and equipped to make safe choices and negotiate wanted outcomes. Sexuality education must become universal and address relationships, consent and safety from an early age both in schools and other settings in which young people congregate, and address gender double standards and power imbalances that are so evident among the young.

Equally important is the need for India’s reproductive health programmes to be inclusive of unmarried young people and recognise their right to information and services. Counselling and contraceptive services must be made available to unmarried young people in non-threatening, non-judgmental and confidential ways. Finally, efforts must be made to ensure a supportive environment; programmes need to address parental inhibitions about discussing sexual matters with their children and encourage greater openness and interaction between parents and children.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by a grant to the Population Council from the MacArthur Foundation, whose support is gratefully acknowledged. We thank John Cleland, KG Santhya, Rajib Acharya, Lea Hegg and Deepika Ganju for valuable comments and support; Mahesh Naik for software development; Aparna Godke, Komal Saxena, Varsha Tol and Dipak Zade for support and assistance; CASP coordinators for field support and our young interviewers for skills in eliciting information on these sensitive topics.

References

- L Abraham, KA Kumar. Sexual experiences and their correlates among college students in Mumbai city, India. International Family Planning Perspectives. 25(3): 1999; 139–146.

- S Awasthi, M Nichter, VK Pande. Developing an interactive STD prevention programme for youth: lessons from a north Indian slum. Studies in Family Planning. 31(2): 2000; 138–150.

- SJ Jejeebhoy, M Sebastian. Young people’s sexual and reproductive health. SJ Jejeebhoy. Looking Back, Looking Forward: A Profile of Sexual and Reproductive Health in India. 2004; Population Council and Jaipur: Rawat Publications: New Delhi, 138–168.

- L Abraham. Redrawing the lakshman rekha: gender differences and cultural constructions in youth sexuality in urban India. South Asia. 24: 2001; 133–156.

- R Masilamani. Building a supportive environment for adolescent reproductive health programmes: essential programme components. S Bott. Towards Adulthood: Exploring the Sexual and Reproductive Health of Adolescents in South Asia. 2003; World Health Organization: Geneva, 156–158.

- Mehra S, Savithri R, Coutinho L. Gender double standards and power imbalances: adolescent partnership in Delhi, India. Paper presented at Asia-Pacific Social Science and Medicine Conference, Kunming. October 2002.

- B Ganatra, S Hirve. Induced abortions among adolescent women in rural Maharashtra. Reproductive Health Matters. 10(19): 2002; 76–85.

- G Sodhi, M Verma, S Schensul. Traditional protection for adolescent girls and sexual risk: results of research and intervention from an urban community in New Delhi. RK Verma. Sexuality in the Time of AIDS. 2004; Sage Publications: New Delhi, 68–89.

- RK Verma, PJ Pelto, SL Schensul. Variations in sexual behaviour in the time of AIDS. RK Verma. Sexuality in the Time of AIDS. 2004; Sage Publications: New Delhi, 327–354.

- RK Verma, M Collumbien. Homosexual activity among rural Indian men: implications for HIV interventions [Letter]. AIDS. 18: 2004; 1845–1856.

- Registrar General of India. Census of India, 2001. At: <http://www.censusindia.net>. Accessed 8 August 2006.

- National AIDS Control Organisation. National AIDS Prevention and Control Policy. New Delhi: NACO, 2002.

- Government of Maharashtra State. Economic Survey of Maharashtra 2005–06: Selected socioeconomic indicators of states in India. Government of Maharashtra. At: <www.maharashtra.gov.in>. Accessed 3 September 2006.

- J Cleland. Illustrative questionnaire for interview–surveys with young people. J Cleland. Asking Young People about Sexual and Reproductive Behaviours. Illustrative Core Instruments. 2001; World Health Organization: Geneva.

- Ganatra B. Abortion in rural Maharashtra. Unpublished survey instrument, 1995.

- Patel V. Adolescents in Goa. Unpublished survey questionnaire, 2002.

- International Institute for Population Sciences; Population Council. First time parents project: Unpublished baseline survey questionnaire, 2002.

- Sebastian M, Grant M, Mensch B, et al. Integrating adolescent livelihood activities within a reproductive health programme for urban slum dwellers in India. Unpublished survey questionnaire. New Delhi: Population Council, 2004.

- G Sodhi, M Verma. Sexual coercion amongst married adolescents of an urban slum in India. S Bott. Towards Adulthood: Exploring the Sexual and Reproductive Health of Adolescents in South Asia. 2003; World Health Organization: Geneva, 91–94.

- Alexander M, Garda L, Kanade S, et al. Formation of partnerships among young people in Pune district, Maharashtra. Unpublished paper, 2006.

- KT Silva, SL Schensul, JJ Schensul. Youth and sexual risk in Sri Lanka. Women and AIDS Programme, Phase II: Research Report Series No.3. 1997; International Centre for Research on Women: Washington DC.