Abstract

Despite rhetorical attention there is little programmatic guidance as to how best to ensure that women and men living with HIV have access to sexual and reproductive health services that help them realise their reproductive goals, while ensuring their human rights. A dynamic relationship exists between the manner in which health services and programmes are delivered, and the individuals who seek these services. A review of the literature shows clear gaps and highlights areas of concern not yet sufficiently addressed. The delivery and use of health services and programmes is shaped by the underlying determinants of people's access to and use of these services, the health systems in place at community and country level, and the legal and policy environment these systems operate in. Few governments can provide the full range of services that might be required by their populations. In most places, people access health services from a variety of formal and informal providers, and health-related behaviour is influenced from many directions. The synergistic roles of health systems, law and policy and underlying social determinants in helping or hindering the development and delivery of adequate programmes and services for HIV positive people must be addressed.

Résumé

Malgré une attention rhétorique, il existe peu de conseils sur la meilleure manière de garantir l'accès des hommes et des femmes vivant avec le VIH aux services de santé génésique qui les aideront à réaliser leurs objectifs de procréation, tout en respectant leurs droits humains. Une relation dynamique existe entre la manière dont les services de santé et les programmes sont assurés et les individus qui recherchent ces services. Une étude des publications montre clairement des lacunes et dégage des domaines insuffisamment abordés. Les prestations des services et programmes de santé et le recours à ceux-ci sont façonnés par les facteurs sous-jacents qui déterminent l'accès des personnes à ces services et l'utilisation qu'elles en font, les systèmes de santé en place aux niveaux communautaire et national, et l'environnement juridique et politique dans lequel ces systèmes fonctionnent. Peu de gouvernements peuvent offrir tous les services qui seraient nécessaire à la population. En général, les patients ont accès aux services de santé par le biais de différents prestataires formels et informels, et le comportement sanitaire est influencé par de nombreuses orientations. Il faut s'intéresser à la synergie des systèmes de santé, de la législation et des politiques, et des déterminants sociaux sous-jacents qui aide ou entrave le développement et la prestation de programmes et services appropriés pour les personnes séropositives.

Resumen

Pese a la atención retórica, no existe mucha orientación programática en cuanto a la mejor forma de garantizar que las mujeres y los hombres que viven con VIH tengan acceso a servicios de salud sexual y reproductiva que les ayuden a realizar sus objetivos reproductivos, a la vez que garantizan sus derechos humanos. Existe una relación dinámica entre la forma en que los servicios y programas de salud son proporcionados y los usuarios. Una revisión del material publicado muestra las brechas y resalta las áreas preocupantes que no han sido tratadas lo suficiente. La prestación y el uso de servicios y programas de salud es definida por los determinantes de la accesibilidad y uso de estos servicios, los sistemas de salud en el nivel comunitario y nacional, y el ambiente jurídico y normativo en el cual funcionan estos sistemas. Pocos gobiernos pueden proporcionar la gama completa de servicios que pueda necesitar la población. En la mayoría de los lugares, las personas acceden a los servicios de salud por medio de una variedad de prestadores de servicios oficiales y extraoficiales, y el comportamiento relacionado con la salud es influenciado desde muchas direcciones. Es imperativo tratar las funciones sinérgicas de los sistemas de salud, derecho y políticas y los determinantes sociales implícitos en ayudar o perjudicar la creación y prestación de programas y servicios adecuados para las personas seropositivas.

There is increasing recognition around the world that existing public health policies and programmes often fail to respond to the sexual and reproductive health-related rights, needs and aspirations of people living with HIV.Citation1 Urgent action is required to address these failures.

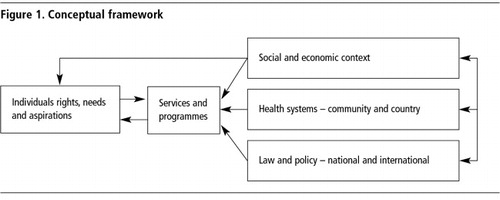

How can the rights, needs and aspirations of HIV positive women and men best be achieved, including support for appropriate self-care and demand for services? A dynamic relationship exists between the manner in which health services are delivered and the individuals who seek these services. Furthermore, the delivery and use of health services are shaped by the health systems that are in place, both at community and country level, the national and international legal and policy environment within which these systems operate, and the overall social and economic context of people's access to and use of these services.

Using the framework in , this paper provides an overview of policy and programmatic issues relevant to ensuring that women and men living with HIV have access to sexual and reproductive health services and programmes that help them to realise their reproductive goals, while ensuring the respect, protection and fulfilment of their human rights. It is only when all sections of the figure depicted above are concurrently taken into account that appropriate services and programmes can be conceptualised, delivered and accessed by the people who need them.

Although the sexual and reproductive health-related rights, needs and aspirations of HIV positive women and men are very similar to those of men and women not infected with HIV, some key biological and social differences require specific attention. For example, the increased biological susceptibility to certain medical conditions of populations with high prevalence of HIV may require prioritising services that address these conditions. In addition, societal attitudes that stigmatise HIV may necessitate increased attention to such issues as privacy and confidentiality. Understanding what people living with HIV seek from health services and programmes is necessary to ensure that these are appropriately tailored to meet their needs.

In the context of sexual and reproductive health and HIV, where taboos and stigma persist, it is imperative to assess how social and economic contexts impact on demand, access, use and quality of health services and programmes. Some of these broader dynamics have a negative impact on the lives of HIV positive people, including poverty, gender inequality and stigma. Others are positive, such as participation and accountability systems, social capital within particular communities and broader social commitment to solidarity or equality. This paper draws attention to key aspects of the socio-cultural and economic context that affect the experiences of HIV positive men and women.

Historically, systems for the delivery of HIV and sexual and reproductive health services developed in parallel whilst influencing each other; in many cases, they are now slowly being brought together or linked. As the primary focus of HIV programmes has shifted from information and education on the prevention of HIV infection to the provision of treatment for AIDS, there is an increased need for a functioning health system that can deliver both HIV and sexual and reproductive health services. Convergence, therefore, is increasingly recognised as an imperative. The time is right to harness the success of, and political commitment to, HIV programmes to strengthen sexual and reproductive health services for both HIV positive people and the population more generally.Citation2

The international human rights framework provides that national governments must put into place laws, policies and practices that enable HIV positive women and men to fulfil their sexual and reproductive health needs and aspirations. States have a legal obligation to promote and protect the human rights of people living with HIV, including their rights related to sexual and reproductive health. Attention to human rights in shaping the response to HIV and sexual and reproductive health, however, creates opportunities as well as obligations. A human rights approach to HIV emphasises principles such as the participation of affected communities and non-discrimination in shaping and delivering policies and programmes. These principles are now understood to contribute significantly to broader public health goals, not only for people living with HIV but for populations as a whole. The evidence base for how rights-based approaches contribute to work in both HIV and sexual and reproductive health has been strengthened over time. Likewise adherence to the legal obligations relating both to sexual and reproductive health and to the lives of people living with HIV are reflected in a growing number of international policy and programme guidelines.Citation1 Nevertheless, international public policy attention bringing together efforts in sexual and reproductive health and HIV, in particular the specific sexual and reproductive health rights and needs of people living with HIV, is unfortunately still a relatively new phenomenon.Citation3

Drawing from , this paper examines the synergistic roles of individuals' rights, needs and aspirations, the socio-economic context, health systems, and law and policy in helping or hindering the development and delivery of adequate programmes and services for HIV positive people. The conclusion highlights the importance of the linkages between these areas for effective design and delivery of services and programmes.

Rights, needs and aspirations in relation to sexual and reproductive health of people living with HIV

In most ways, the sexual and reproductive health-related rights, needs and aspirations of positive people are no different from those of people who are not infected with HIV. For example, all people have the right “to decide freely and responsibly the number, spacing and timing of their children and to have the means to do so…”.Citation4 All women need a skilled attendant at birth to reduce the risk of maternal and newborn morbidity and mortality. Most young people, whether or not they are living with HIV, aspire to understand the physical changes in their bodies and how to responsibly enjoy their emerging sexuality.

However, people living with HIV have important, specific sexual and reproductive health-related needs and aspirations as well. In biological terms, people living with HIV are more vulnerable to certain sexual and reproductive health problems than people who are not infected with HIV. A good example is pre-cancerous cervical cell abnormalities, which may be more prevalent and more persistent in women with HIV.Citation5 In addition, people with HIV have some unique sexual and reproductive health needs, for example, treatment and support to reduce the risk of HIV transmission to infants during childbirth and breastfeeding.

There are also social and structural factors of particular or unique relevance to HIV positive people. For example, women with HIV may be under different pressures and expectations than other women as to whether or not they should have children, and positive men and women often report pressure and expectations that they should not be sexually active, even when asymptomatic.Citation6 These pressures and expectations may be imposed by family, community or health services and even through legal and policy directives. For example, research in Brazil indicates that many women living with HIV do not voice their desire to have children to their health service provider for fear of a negative reaction.Citation7 Qualitative research demonstrates that one of the most pervasive and destructive experiences for people living with HIV is the stigma and discrimination they experience within the health care setting. This often takes the form of disparaging remarks and substandard service related both to their HIV status and to the association of HIV on the part of providers with marginalised or illegal behaviours.Citation8

In international legal terms, sexual and reproductive health is addressed primarily within a human rights framework. The focus of human rights is on state obligations, but sexuality and sexual health remain inadequately protected. Missing is recognition of the boundaries of State responsibility for sexual activity outside of reproduction, and for a satisfying sex life. Reproductive rights, as just one component of sexual and reproductive health and rights, do not offer sufficient protections for all that falls within this broad concept. The absence of accepted language within international legal discourse to capture State responsibility for ensuring an environment capable of enabling sexual health is detrimental to the sexual well-being of HIV positive people, as well as the entire population.

While human rights are universal and most sexual and reproductive health needs and aspirations are common to people whether or not they live with HIV, there are nevertheless some principles related to the rights, needs and aspirations of HIV positive women and men that require specific attention. Based on human rights norms and the effectiveness of these approaches, the most important of these principles are that:Citation9

| • | HIV positive people must be able to make non-coerced and autonomous decisions regarding sexuality and fertility. | ||||

| • | Through the health system, HIV positive adults and young people must have access to relevant information, counselling and services tailored to their sexual and reproductive health-related needs. | ||||

| • | HIV positive people must be entitled to confidentiality, and their fully informed consent must be sought in all service provision. | ||||

| • | Whenever possible, HIV positive men and women should be given the opportunity to involve their partners in decision-making and action regarding sexuality, reproductive health and childcare. | ||||

Only in recent years have the sexual and reproductive health concerns of HIV positive people been recognised in the health research and policy literature. Some of the issues that have emerged from these studies are the following:

The desire to have children among people living with HIV is primarily related to the number of children they already have

Many health professionals perceive the pregnancy-related needs of women living with HIV to be almost exclusively related to the prevention of mother-to-child transmission of HIV.Citation10 This has led to insufficient attention being paid to other needs in relation to childbearing. Studies on reproductive choice among HIV positive people have yielded conflicting results. One study showed positive women were less likely than their negative counterparts to want to have more children, but the overall study population already had an average of 2.8 children.Citation11 Studies carried out in Brazil among HIV positive men and women concluded that a significant proportion did want to have children in the future, including 43% of positive men (significantly higher among those with no children), and 14–20% of women (significantly associated with having only one or no children).Citation12 Some studies have highlighted that people living with HIV want children so as to “leave something of themselves behind” or because children represent “normality”.Citation13 Research in Brazil and Zimbabwe has also shown that positive people fear they would get a negative reaction from their health workers if they were to voice their intention to have more children and that outside the clinic health workers have openly expressed disapproval of HIV positive people's decision to have children.Citation6,12

HIV testing must be voluntary and include counselling

Efforts must be made to ensure that positive people feel supported in learning their HIV status. This requires that HIV testing be voluntary, include appropriate pre- and post-test counselling, and be ethical, i.e. be conducted with the primary aim of supporting positive people in staying connected to health services and helping negative people remain negative.

Draft guidelines on provider-initiated HIV testing and counselling (PITC) have recently been circulated by WHO/UNAIDS for comment. Shifting the responsibility for initiating HIV testing away from the service user to the service provider, the guidelines promote the routine offer of an HIV test to all users of health services in settings where the HIV epidemic is generalised, and in certain health care settings where the epidemic is concentrated or low-level. The stated purpose of scaling up PITC is “to facilitate earlier and more widespread knowledge of HIV status and greater access to HIV prevention, treatment, care and support”.Citation14 In order to achieve this, the new guidelines strive for “complementarity between clinical, public health and human rights objectives”.Citation15 On paper, much of the draft guidance appears to strike a reasonable balance of attention to each of these issues; great care will be needed to ensure that this balance is retained in the implementation of HIV counselling and testing programmes and services.

In settings where rapid diagnostics for HIV are unavailable, the number of people being tested is far larger than the number of people collecting their test results. Reasons for this may include being unable to return to the health clinic due to other responsibilities, such as childcare. However, some people have been unwilling to return for fear of a positive diagnosis or because they took the test following pressure from a health worker. Rapid testing methods mean that testing and receiving the result can be done in one visit, thus removing one of the barriers to learning test results. Services must ensure testing is voluntary, regardless of the type of test used, and provide appropriate support to people at the time of their diagnosis.

Many women find out that they are HIV-positive while being screened during antenatal care or even at the time of delivery

In places where HIV counselling and testing services are not widely available or used, antenatal care may be the only place where HIV testing is available. This is likely to become increasingly true as the new WHO/UNAIDS guidelines on PITC recommend that, in generalised HIV epidemics, antenatal, childbirth and post-partum health services are the most important health facilities for the implementation of PITC. In addition to the concerns raised by testing in this context, the manner in which the test result is delivered by the service provider and the extent of support offered to women with a positive diagnosis, services need to recognise that women also have to assimilate information about what this status means for them, their partner and their unborn child, consider disclosure to family and friends and decide whether or not to continue with their pregnancy. This decision may depend heavily upon how each woman weighs the conditions of her lifeCitation8 as well as the support systems she has in place.

After receiving a positive diagnosis, some people withdraw from sexual activity

The reasons for this may include a partner dying or leaving, illness, loss of sexual desire, fear of spreading disease and fear of re-infection. About half of the women in a study in Thailand had sexual relations after discovering their positive status, but only 31% said they were still sexually active at the time of the study, which was on average 32 months after receiving an HIV positive diagnosis.Citation8 Services concerned with the sexual health of positive people need to help them to voice such concerns and come to terms with how this affects their sexuality.

The differences in the life experience and sexuality of all HIV positive people must be considered in all service delivery related to sexual and reproductive health

Services must recognise that people with HIV seeking counselling and services related to sexual and reproductive health may be engaged in sexual activity that goes beyond the experience and knowledge of the care provider. They must therefore be sensitised to the needs of individuals and couples whose sexual lives they may not understand, recognise or accept.

HIV-positive women may be more affected by certain reproductive health-related complications than seronegative women

These include miscarriage, post-partum haemorrhage, puerperal sepsis and complications of caesarean section.Citation16 Services need to be aware of these potential risks and provide appropriate training and interventions.

HIV positive men and women have a greater risk of contracting human papillomavirus (HPV) and other sexually transmitted infections

In men, HPV symptoms are often minimal and treatment may not be sought, but the risk of transmission to partners remains. Men may, however, suffer consequences from HPV infection ranging from genital warts to ano-genital cancers, with the latter a particular concern for men who have sex with men.Citation17 In women, certain strains of HPV are associated with cancers of the lower genital tract and cervical cancer (an AIDS-defining illness).Citation18 Vaccination against HPV, and screening and treatment for cervical and other reproductive cancers are crucial for all women irrespective of their HIV status, but HIV positive women are at higher risk of cervical cancer at younger ages than other women. Visual inspection, cryotherapy and loop electrosurgical excision are low-cost treatment alternatives for resource-constrained settings and must be provided where possible.

HIV positive women and men require access to family planning services in addition to condoms

Dual protection refers to strategies that provide protection from both unwanted pregnancy and STIs, including HIV. Dual protection can take various forms, including the use of condoms alone or the use of condoms with another form of contraception and the back-up of emergency contraception, for added protection against unwanted pregnancy. Unless a couple know they are free of HIV and other STIs and are not at risk through sexual activity with others, condoms are the key component of dual protection. Thus, better interventions are needed which support women as well as men to use condoms during sexual intercourse, both for those living with HIV and those who may be in a discordant couple or when one or both partners are engaged in sexual activity with others who may be at risk.

Most methods of contraception can be used irrespective of HIV status.Citation19Citation20 However, the limited data available suggest that some complications may exist with regard to IUD use in the presence of STIs or AIDS and with regard to hormonal contraceptive use alongside certain drugs.Citation19

Reasons reported by HIV positive women for not using condoms include their partners not wanting to, not knowing their HIV status or not fearing infection, as well as the unavailability of condoms, and lack of knowledge as to how to use condoms.Citation8 The baseline assessment of a study in Zambia showed that 30% of HIV positive women reported condom use in fewer than half of sexual encounters, suggesting that further sensitisation is required as to the importance of consistent condom use.Citation21

HIV positive women may experience unwanted pregnancy

HIV positive women may experience unwanted pregnancy, whether as a result of contraceptive failure, lack of contraceptive use or sexual assault. Sexual and reproductive health services must be able to address unwanted pregnancy for positive women as well as to provide them services for sexual assault. Integrated services for sexual assault include support for contact with police, STI testing and treatment, emergency contraception or abortion if required.Citation22 Access to safe abortion that is not against the law should be made available, just as it should for HIV negative women.Citation23Citation24 Where abortion services are illegal and unsafe, post-abortion care should be widely available to deal with complications. Although abortion is illegal in Thailand, out of 49 positive women interviewed who became pregnant, 28 chose to have an abortion.Citation8 Two of the main reasons cited by women in a study in South Africa for not wanting children were fear of having an infected child and fear of being unable to financially support a child.Citation13

HIV positive women should have a choice of mode of delivery in childbirth

Before the widespread use of antiretrovirals, elective caesarean sections were relatively common among positive women in the industrialised world. However, for women who are on antiretroviral therapy, for whom the probability of mother-to-child transmission is much reduced, the risks of an elective caesarean section (such as obstetric complications or premature birth of the infant) may well outweigh the benefits.Citation25 Services in all parts of the world must provide information to HIV positive women when they are pregnant so that they can make an informed choice of mode of delivery.

HIV positive women need specific counselling related to breastfeeding

During pregnancy, HIV positive women need information on the relative risks of breast vs. replacement feeding relevant to their living conditions, the preparation of replacement feeding by the mother/caregivers, costs of replacement feeding, possible obstacles to being able to continue her chosen feeding method if she needs to move (e.g. refugees or seasonal labourers), and when and how to carry out abrupt weaning for mothers who have been exclusively breastfeeding. Guidance documents developed by international organisations can serve as models for local materials but explicit attention to breastfeeding is needed from relevant services.Citation9,26

Drug interactions have important implications for positive people

In addition to potential drug interactions between certain antiretrovirals and oral contraceptives, HIV positive women receiving drug treatment should be informed that some medications used to treat opportunistic infections, such as rifampin, may reduce the effectiveness of some oral contraceptives.Citation19

The need for both prevention and treatment from health services

Due to the absence of effective treatment in the past, HIV programmes initially focused primarily on prevention efforts. Sometimes these were attached to existing sexual and reproductive health services while at other times they were set up in parallel, as there was little recognition of the need for prevention messages to be delivered within sexual and reproductive health service settings. As antiretroviral and other treatments are becoming increasingly available, international attention has shifted away from prevention, yet it is critical that a balance be maintained between prevention and treatment and that organisations providing each of these services work closely together. Many organisations promoting the prevention of HIV also promote the prevention of other STIs, both of which are critical components of sexual and reproductive health care for HIV positive people. Due to the fact that many HIV prevention programmes were initially set up to be independent of health services, such collaboration might require working with organisations outside the health sector.

Confidentiality remains a critical issue for many positive people

Pervasive stigma continues to surround HIV. Fear of gender-based violence, for example, is a major disincentive for women to finding out their HIV status, which must be recognised and addressed in health facilities.Citation27 Services must ensure confidentiality of test results and provide support to positive people who wish to disclose their status to their partner or other family member, and must be able to decide themselves how and when to do this. Health service providers should, of course, not disclose the HIV status of any patient without their informed consent. In many cases, as a result of providers' disclosure of a person's HIV status to other staff or community members, people have been afraid to return to them for services.Citation8 The fear of stigma and discrimination that can lead to non-disclosure impacts not only on the life of the person with HIV but on their partner, children and other family members.Citation28

Services for HIV positive men and discordant couples are almost ignored

Despite increasing attention to the sexual and reproductive health concerns of positive people and the services needed to support them, there are clearly areas that are not yet being sufficiently addressed. Importantly, men are almost entirely ignored. Although much has been published on how to increase men's involvement in sexual and reproductive health in general, there is a dearth of research on how to ensure that appropriate services are made available to positive men or men in discordant couples. For example, HIV positive men who have experienced sexual assault, e.g. in prison, need STI testing and treatment. Much of the work to date on integrating HIV services into sexual and reproductive health services has focused on bringing HIV prevention into maternal and child health services which, with the exception of the MTCT-Plus initiative in a small number of sites,Citation29 has benefited positive men very little if at all.

The minimal literature that does consider the needs and aspirations of positive men shows that many wish to remain sexually active and have children.Citation30 Furthermore, social pressure on men to prove their virility is a neglected area. It is critical that models be developed which can support positive men and discordant couples to remain sexually active and have children in a safe manner. In general, increased efforts are needed to ensure a better understanding of how health services can meet the needs of positive men.

Male circumcision has emerged as an HIV risk reduction method for HIV negative men engaged in vaginal sex

WHO and UNAIDS recently recommended that male circumcision be promoted as part of a comprehensive HIV prevention packageCitation31 and in recent months there has been a lot of discussion about the potential of this intervention to reduce heterosexual transmission of HIV. Trials have shown that male circumcision can reduce the risk of HIV acquisition by men through vaginal sex by approximately 50-60%, but without similar benefits for women.Citation32 However, a number of issues remain to be considered to move beyond the rhetoric, if policy and programmatic guidance is to help ensure this intervention can deliver on its intended benefits and reduce new infections.

Access to services and the range of services available remain inadequate

Our review of the literature found almost no discussion on how the services that are deemed necessary for HIV positive people should be made available to ensure that they can be accessed adequately. There is also little documentation of successful models for strengthening sexual and reproductive health services to meet the needs of people living with HIV or for linking them with HIV services. Further, while the rights of positive people exist at a rhetorical level and permeate much of the literature, the concrete integration of rights into how services are delivered is still largely absent.

Finally, there are few research or policy efforts that focus on aspects of a satisfying sex life for HIV positive people and their partners that are not related to reproduction. The sexual well-being of positive people, like all people, involves considerably more than having children, but the literature does not address these broader issues.

Social and economic context

It has long been recognised that any given social and economic context has a very significant impact on health outcomes. The influence of context on health can be quite direct, as reflected in the impact of hunger or inadequate transportation infrastructure on health outcomes, including reproductive health. The indirect role of socio-economic context is also important; these realities enable or undermine health systems and services, and reinforce or minimise the impact of legal and policy actions. For example, where petty corruption in public services is tolerated, access to health services may be undermined by service providers' demands for bribes from service users. Similarly, legal regulations supporting gender equality are often undermined by social norms of male dominance.

Some social dynamics – both positive and negative – are of particular relevance to the lives of people living with HIV:

Poverty and inequality

The correlation between poverty, inequality and vulnerability to HIV and to poor access to sexual and reproductive health services is striking.Citation33 Poverty is also strongly associated with poor reproductive health outcomes. For example, malnutrition is a major contributor to both maternal and newborn deaths, and in poor communities women's access to services relating to maternal and neonatal complications is particularly limited.Citation34

The association of poverty with HIV infection is more complex. Evidence points to income and gender inequality in society and associated patterns of multi-partner, quasi-commercial sex being as important as poverty per se in terms of vulnerability to HIV infection. For example, a study in Rwanda showed that women whose main partners had higher education and income were more likely to be infected with HIV than others. These findings are echoed in other research, especially in southern and eastern Africa. Among women served by family planning clinics in Tanzania in one study, women with highly educated partners were five times more likely to be infected with HIV than those women whose partners had no schooling.Citation35 This highlights the perverse interactions between different forms of inequality and their ultimate impact on HIV infection.

Once someone has HIV, however, faster disease progression and poorer access to care are clearly associated with poverty. In addition, there is strong evidence that poverty affects service and information availability and access, and quality of service provision in relation to both HIV and sexual and reproductive health. In most parts of the world, there are fewer public and private sector service delivery points in areas where poor people are more likely to live, whether rural or urban. Formal and informal payments are also barriers to accessing services for the poor, as is the cost of transport to services, even if services themselves are free.

There are strong arguments that both short- and long-term approaches to poverty reduction should be adopted in order to ensure access to essential services. These include waiver systems whereby patients who cannot afford to pay for medication or health services receive them free of charge, and transport subsidies for those who cannot attend health appointments without this support. In the longer-term, all poverty reduction programmes must take into account the vulnerability of HIV positive men and women, as well as their need for routine access to health and social services.

Gender inequity and inequality

It is generally understood that the biological vulnerability of women to HIV infection is exacerbated by social, cultural, economic and political realities at international, national, community and inter-personal levels. So too is the disproportionate role of women in care-giving.Citation36 The scale of this problem varies across countries and cultures but these vulnerabilities have been recognised in numerous international documents,Citation37Citation38 even as they remain insufficiently addressed in policies and programmes.

Similarly, cultural expectations regarding male behaviour in most parts of the world have been seen to encourage sexual risk-taking and discourage protective behaviour. Once men are very ill with AIDS they are more likely than women to access care and treatment in many settings. However, men are often less likely to seek assistance or support when symptoms of ill-health first appear, decreasing the likelihood of early diagnosis of a variety of conditions, including STIs and HIV.Citation39

There is a very strong evidence base demonstrating “that improved education for women, including adult literacy and empowerment, have been associated with improved child health and reduced fertility”.Citation40 Moreover, reproductive health and HIV interventions “that have been most integrated with the economic, education, and/or political sectors have resulted in greater psychological empowerment, autonomy and authority, and have substantially affected a range of health outcomes”.Citation40

HIV-related stigma and discrimination

Stigma has been defined as holding and expressing derogatory social attitudes and beliefs or hostile behaviour towards members of a specific group. Discrimination concerns the legal, institutional and procedural ways people are denied access to their rights because of their real or perceived HIV status.Citation41 HIV-related stigma and discrimination have restricted the success of HIV prevention, care and treatment programmes and reduced the willingness of people with HIV to disclose their status or to seek out sexual and reproductive health services.Citation42 UNAIDS calls the stigma and discrimination associated with HIV “the greatest barriers to preventing further infections, providing adequate care, support and treatment and alleviating impact. HIV/AIDS-related stigma and discrimination are universal, occurring in every country and region of the world”.Citation43

There were hopes that with the advent of antiretroviral treatment, stigma and discrimination surrounding HIV would dissipate; despite ongoing research, there is not yet conclusive evidence to support this hope. Addressing stigma and discrimination effectively requires long-term commitment and interventions at many levels.

Community participation and ownership

The greater involvement of people living with HIV in responses to HIV has been promoted for over a decade as a cornerstone of good practice and support for beneficial programme outcomes. For example, a four-country operations research study sponsored by the International HIV/AIDS Alliance and Population Council/Horizons concluded that the involvement of positive people in community HIV responses can lead to overall improvement in their health conditions, psychological as well as physical. However, participation per se did not assure positive results for the individuals or the programmes; it was the nature and process of participation that substantially influenced outcomes.Citation44

Similarly, there is relatively little literature on the association between empowerment efforts and health outcomes for the disadvantaged more broadly, but those studies that do exist underline the positive contributions of empowerment. A WHO review of the few published studies that explicitly tested the hypothesis that community participation in decision-making would show additional benefits in health or health care found that all the studies demonstrated measurable contributions from empowerment efforts.Citation40

Social capital

There is some evidence from Asia, Latin America and a number of wealthy countries that individuals with stronger family and community ties are less likely to be infected with HIV, and if infected more likely to be accessing needed care and treatment than others with similar income and education levels but with weaker ties. Greater sense of community, belonging to a network, trust, perceived neighbourhood control and participation are all independent predictors of better self-reported health and fewer depressive symptoms.Citation40 These and other findings have significant implications for the effective delivery of sexual and reproductive health services.Citation45–47

The role of health systems

How do health system issues shape the service and programme packages available to positive people, as well as their access to them? And how can an ideal package be achieved?

Key institutions involved in funding public health in developing countries such as WHO, DFID and USAID typically define health systems as the people, institutions and organisations that work together to prevent and treat diseases, as supported by health policies, finance systems, the health work-force, supply systems, service management and health information and monitoring systems.Citation48Citation49 While this framework is often interpreted to emphasise the public sector delivery of health care services, health promotion and demand creation are equally important outcomes of a strong health system, and around the world the private sector (for profit and non-profit) is often as important or more important to service delivery as the public sector. When considering the sexual and reproductive health and rights of positive people, it is essential to ensure that in strengthening health systems particular attention is paid to self-care and demand creation, as well as to health care service provision by private for-profit, traditional and non-profit institutions and organisations.Citation50

Parallel histories

HIV and sexual and reproductive health services have developed in parallel, whilst influencing each other, and this history is affecting how they are now slowly being brought together. The earliest responses to HIV around the world were organised by people with HIV themselves, their families and loved ones and, soon afterwards, by fledgling HIV-focused community organisations. While the very first organised services and programmes focused on the immediate care needs of people with advanced illness, it was not long before the HIV movement was also inventing and then promoting “safer sex” as the foundation of prevention. From the earliest days of the response to HIV, there have been policy, programmatic and conceptual links between sexual and reproductive health care on the one hand, and HIV prevention, treatment and care on the other.

In the 1980s, these intersections were most visible in the way the HIV movement borrowed and adapted concepts and tools from both sexual and reproductive health and the broader women's health movement. “Safer sex” was simply the adoption and promotion of the condom and

non-penetrative sex for HIV prevention, drawing on well-established roots in contraception and STI prevention. The central strategy of promoting the involvement of people living with HIV in policy development and programme delivery was in many ways also borrowed from the women's health movement, as was the recognition that public health required attention to politics in addition to service delivery. Early strategies linking promotion and protection of human rights to HIV prevention and care drew heavily on gender analysis and the women's health movement as well.In parallel to the emergence of the response to HIV, movements away from “population control” and towards “family planning” and women's health and rights were coming together and changing each other. Activists, non-governmental organisations, service providers, programme managers and policymakers were all crucial to this evolution. A defining moment occurred at the 1994 Cairo International Conference on Population and Development (ICPD), where governments set out an internationally accepted definition of reproductive health and rights, and sexual health, and an agenda for related programme and service development. As summarised elsewhere: “Cairo formally endorsed the notion that family planning should be embedded within a broader package of sexual and reproductive health and rights services, including (but by no means limited to) prevention of STIs such as HIV; the linkage of human rights and service provision approaches; the idea of comprehensive, client-focused programming; and the primacy of national leadership in defining essential packages of reproductive health services”.Citation51 The ICPD Programme of Action was a historical step forward in providing a comprehensive set of recommendations to States for the provision of sexual and reproductive health services. At the same time many people involved in HIV work were highly critical of it for not paying enough attention to HIV, and in particular for ignoring the rights and needs of HIV positive people.Citation52

While ICPD could be seen as a watershed in its recognition of the importance of human rights, health systems, laws and policy, as well as the social and economic context for the availability and use of sexual and reproductive health services, it did not provide a coherent approach for bringing these factors together or for addressing them. Therefore even when there was good will on the part of governments, there was little clarity as to what systematic consideration of these issues could or should mean for how services should actually be delivered and used. Ten years after ICPD some impressive results have been achieved. Developing countries have by and large made good progress at putting in place some required policy changes, even though most donor countries have not been so successful at providing promised resources.Citation52 Often faced with shrinking resources, lack of clarity as to how to bring these diverse concepts together and expanded responsibilities, despite good intentions at the policy level, front-line health workers have had difficulty delivering on ICPD's promises.

In the last years, actors in the sexual and reproductive health field have begun to acknowledge the intricacies of the links between sexual and reproductive health and HIV and have been inspired by some of the innovations and successes in HIV, such as the emphasis on vulnerability reduction in prevention strategies, the use of syndromic diagnosis of STIs in men, the attention given to marginalised and under-served populations, and the innovations which have taken place in social marketing. While the practical agendas of the sexual and reproductive health and HIV communities overlap heavily, with such shared concerns as gender dynamics, sexuality, STIs, pregnancy, childbirth and breastfeeding, translation of these concepts into effective programming with an appropriate balance of HIV and sexual and reproductive health has been slow at best.

There has been relatively little progress in linking the issues operationally and even less in responding to the specific sexual and reproductive health needs of positive people. There are a number of explanations for this slow progress, of different importance in different contexts.

Resistance from the front-line to greater integration or linkage between the two agendas has created formidable obstacles to integration. Sexual and reproductive health care providers have often expressed concern that their services would be stigmatised and undermined by association with HIV-related services.Citation53 Many HIV programme managers have criticised sexual and reproductive health care providers as inadequately skilled to deal with issues of sexuality, HIV care and marginalised populations. Researchers have pointed to a variety of operational risks of service integration, often citing the mixed results of attempts to integrate STI services more effectively into family planning or maternal health care.Citation54

Donor financing has also played a key role, both as an obstacle and a driver, especially in countries dependent on overseas development aid. Development assistance for health has been inadequate overall, but dramatic shifts in donor priorities have had enormous impacts on the services delivered and approaches to their delivery. As only one example, consider the dramatic under-funding of HIV work through most of the 1990s, which then shifted to extreme interest in certain activities after 1999 while a parallel decrease in funding to other sexual and reproductive health issues was taking place. In addition, the norm amongst many donors has been to finance separate, parallel programmes. Finally, the mainstream of international policy and technical guidance has probably both influenced and reflected these trends, effectively keeping HIV and sexual and reproductive health separate from each other over the past years.

Bridging the divide

There have been many changes in approaches to HIV in the last decade, including the discovery and dramatic cost reduction of antiretroviral drugs. With the advent of more affordable therapy, approaches have shifted from a primary focus on preventive education to more sustained inclusion of care and treatment. As a result, there is also increased dependence on a functioning health system through which to deliver these services. The positioning of HIV efforts within national health structures has become critical so as to provide the necessary services, as well as to meet the wide range of health needs of the population, both HIV positive and negative. For the sexual and reproductive health field, once attention and resources shifted to HIV, it became clear that joining with HIV efforts not only made good sense in terms of providing appropriate services but also for accessing resources and harnessing political commitment. Integration, or at least some degree of linkage, therefore, has begun to be recognised as both programmatically and financially attractive.Citation1

Many of those working in the HIV field have been slow to accept the necessity of working closely with those in the sexual and reproductive health field, but despite this, the divide between them is decreasing. In recognition of this, many international donors have expanded their guidelines on HIV-related funding to encompass investment in health systems development with a view to sustainable service delivery, including for sexual and reproductive health services. Concurrently, international policy guidance is also beginning to shift. Four international documents dating from 2004 highlight the linkages between sexual and reproductive health and HIV, and underscore the need for better understanding of and improved response to the sexual and reproductive health needs of HIV positive people.Citation55–58 They also strongly affirm a commitment to the framework of human rights for carrying out this work. The sexual and reproductive health of HIV positive people is a logical point of interface and attention between the two areas of work; at a health systems level this is only just beginning to be recognised.

Convergence of services

Much of the current debate on the relationship between sexual and reproductive health and HIV now focuses on advantages, disadvantages and costs of co-located services vis-à-vis strengthening of linkages between specialised services.

Health service integration aims to increase access to and quality of health services.Citation59 One recent definition involves having various services on offer at the same facility (or through a functional referral system) with health service providers actively encouraging the use of other services during a visit.Citation60 In this context, differentiation exists between physical integration of services in the same location, and linking of services where functional referral ensures that people are directed to the location where the services they require are available. Research has shown that a high proportion of patients referred from one health service to another never follow through with the referral.Citation61 Hence, physical integration may in some cases be preferable to minimise this problem. At other times, it might be considered better to keep services separate, for example because specialised HIV services can be perceived by marginalised populations as offering higher-quality services from more accepting and understanding health workers, in comparison to primary health care or reproductive health services.Citation50 Local public health, economic and socio-cultural contexts are extremely important in determining when each of these variations is preferable, and must be re-evaluated if circumstances change.

As large-scale roll-out of HIV-related programmes begins in resource-constrained settings, some countries are considering situating HIV-related services and programmes within existing sexual and reproductive health and maternal and child health services.Citation62 This has important implications for who will have access to services. With the exception of STI services, sexual and reproductive health and maternal and child health services are almost exclusively the domain of women. Thus, while locating HIV services within them might facilitate access for HIV positive women, positive men are likely to feel inhibited in this predominately female environment. Moreover, women who are not engaged in sexual activity in order to bear children may also feel ill at ease in using these services. At the same time, sexual health services relevant for men are rare, though male circumcision services may contribute to altering this in the coming years. It is therefore necessary to move beyond traditional concepts of sexual and reproductive health service delivery in order to ensure that both HIV positive men and women have sufficient access to the services and care they require.

Physical integration, where services are offered in the same location, is often preferred by service users, at least when the providers are trusted and the location is accessible and welcoming. These caveats are important, because governments and other providers that choose to physically integrate services must also choose whether to structure integrated services to cater to the population as a whole in a geographic area, or to provide a mix of “one-stop shops” for the general population as well as services for specific population groups, such as youth-friendly clinics or integrated services designed specifically for sex workers.

In places where services are integrated, the directionality of integration (i.e. whether HIV services are integrated into existing sexual and reproductive health services or sexual and reproductive health services are integrated into existing HIV services, or both) has important implications, not least in relation to whether health workers have the requisite training needed and in how the services are perceived by the community. Anecdotal evidence suggests that in most instances, HIV services are being integrated into existing sexual and reproductive health services rather than the other way around because sexual and reproductive health services have been developed within government health structures. Many HIV services, on the other hand, have been set up as parallel structures, which are often considered unsustainable. In settings where HIV services are particularly well-developed, this may go the other way. The value of multiple health system entry points for different populations has long been recognised and is reflected in clinics that emphasise one set of services or another.

A number of models may be particularly promising because they allow for incremental improvements within primary health care systems without radical system change. For example, the United Kingdom now encourages a basic package of HIV services and information in all family planning settings, a basic package of family planning information in all specialised HIV and STI settings, and basic training in sexual and reproductive health and HIV issues for general practitioners (family physicians).Citation63 More broadly, the convergence of sexual and reproductive health and HIV care with primary health care is needed, with special attention to integrated management of acute adult illness; integrated management of childhood illness; strengthened roles of general practitioners, auxiliary nurse–midwives and primary health care centres; and links to tuberculosis services.

There are many cases where physical integration is not affordable or practical, and in such circumstances it is important to have functional referral systems that ensure that service users are clearly directed to the location where the services they require are on offer, and supported to ensure follow-up. The nature and extent of service integration will depend on the degree to which existing sexual and reproductive health services are themselves integrated or whether, for example, maternal and child health, family planning, STI and abortion services are offered by separate providers. It is also crucial to recognise that some of the most strategic entry points for these services may be located in other primary and hospital-based clinics – tuberculosis detection and treatment programmes are particularly important in this regard.

Advantages of decentralisation

The extent to which a country has decentralised its health system has an impact on the range of services available to patients as well as the mechanisms through which these are made available. Increasing decentralisation requires better qualified staff in peripheral areas as they have increased responsibility for decision-making. The advantage in this is that they can ensure that service delivery is appropriate to the local culture and context. Moreover, in a decentralised system, sexual and reproductive health services for positive people can be prioritised in areas of high HIV prevalence more than in areas of low prevalence.

In addition to considering the overall impact of decentralisation on the services offered to HIV positive people, each of the components of the health system can be seen as a mechanism through which a broad range of sexual and reproductive health services can be strengthened, and each individual service offered can also be considered in the context of the broader health system. Thus, to strengthen prevention of mother-to-child transmission (PMTCT) services, for example, a range of activities could be developed including training of health service providers, and co-location of HIV counselling and testing, PMTCT and antenatal and delivery services, with common funding mechanisms. By targeting different components of the health system with both sets of needs in mind, service delivery may be markedly improved for affected populations.

New approaches to service delivery

Often, it is only the delivery mechanism that will differ according to the HIV status of the patient rather than the range of services themselves. For example, although dual protection can be promoted to everyone seeking family planning, this information may additionally be provided to HIV positive people during post-test counselling. The attitudes of health care providers when promoting family planning and providing other sexual and reproductive health services to people with HIV must also be considered as they will have a significant impact on how positive people determine their choices in relation to sexual and reproductive health.Citation64

In addition, both men and women need access to private space within facilities in which to discuss, with their partners if they wish, HIV and sexual and reproductive health issues with health service providers. Research from Brazil shows this space is lacking for both men and women who have HIV,Citation10 yet it could make a tremendous difference to them.

Health care workers' attitudes, fears and concerns

Health care workers in many parts of the world have expressed fear of working with positive patients due to the possibility of acquiring HIV in the workplace. As a priority measure, education of health care workers must be provided as to what are adequate means of protection and the importance of using universal precautions.Citation65 In addition, recognising that there is a risk, albeit a very small one, some countries have prioritised access to free antiretrovirals for health care workers who may have been exposed, e.g. through needlestick injuries.

People with HIV often face discrimination and even the refusal of treatment by health care professionals. Providers may don three or four sets of latex gloves and other protective gear unnecessarily. Pregnant women have received directive counselling urging them to terminate their pregnancy regardless of their own wishes. Such behaviour is both unprofessional and incompatible with general human rights concerns and anti-discrimination policies.Citation66 Policies and programmes are needed to raise awareness and encourage sensitivity amongst health care providers, to combat stigma and discrimination and to ensure that positive people receive the health care they need.

Human resources development

A critical issue for health systems in many parts of the developing world is that of insufficient human resource capacity. Adapting medical and nursing school curricula to include modules on the sexual and reproductive health needs of people with HIV will, in the long term, produce significant benefits. To have an impact in the shorter term, continuing education programme curricula should cover these matters. Malawi is currently implementing a national programme to deliver an essential health package, which includes a major scale-up of HIV-related services and also takes into account the country's high maternal mortality and morbidity rates. Despite these and other positive efforts, around the world adequate staffing remains the single largest challenge.Citation67

Ethical guidance for health professionals

Even with education, training and information, health care workers in many parts of the world are required to seek institutional guidance before offering reproductive options and services to positive people. In addition when positive people request access to reproductive health technology in places where these are available, few ethical guidelines exist for the delivery of these services. A framework for decision-making and guidance is needed to support ethical review boards and other institutional decision-makers to provide needed services, such as sperm-washing or infertility treatment, to HIV positive people. Thailand has useful models which may be replicable in other parts of the world.Citation68 The Medical Foundation for AIDS and Sexual Health in the UK has a number of publications with recommendations on standards for sexual and reproductive health and HIV services that may also be adapted.Citation69

Financing flows: national and international

Many countries that receive donor assistance are choosing to channel health-related monies through sector-wide approaches,Citation70 whereby money goes to the Ministry of Health of the recipient government, which then allocates the funds according to its own priorities. This has caused a worrisome loss of funding for sexual and reproductive health services due to the low importance often accorded to these services by national governments, and efforts are currently being made by some European donors to redress this negative trend.Citation71

As money for HIV is generally channelled through separate mechanisms, HIV-related activities may be carried out separately from other health activities. Although general health funding is under-resourced, some countries are being flooded with HIV monies which they are struggling to absorb and spend. International donor funding mechanisms should be evaluated, with particular attention to their impact on the delivery of sexual and reproductive health services, including to HIV positive people, to ensure that a broad range of health concerns can be addressed, both inside and outside the health system, including HIV.

In some places HIV funds are managed by the Office of the President or Prime Minister while all other health funding is channelled through the Ministry of Health or Finance, with different regulatory, accounting and reporting requirements. While intended to ensure attention to the larger development impacts of HIV and strengthen a multi-sectoral response, this nonetheless results in a continued distinction between HIV and other health-related activities. If all HIV funding continues to be channelled through parallel mechanisms, financial intermediaries are needed to coordinate the requirements of those bodies responsible for the financial management of health funding generally with those responsible for HIV.

Innovative examples are needed, but documentation of successful efforts is scarce. Mozambique's recent national HIV plan is nested within its national health strategy and, although funded through a pooled funding mechanism separate from the rest of the health system, it covers the integration of some HIV-related activities into existing sexual and reproductive health infrastructure.Citation72 Efforts should be made to evaluate the impact of this approach, as well as to collect relevant experiences from other countries.

The role of law and policy

The legal and policy environment shapes the availability of health services and programmes as well as the degree to which they are responsive to the individual needs and aspirations of positive people. Law and public policy are also key tools with which to influence social and economic context: reinforcing positive social determinants and beginning the process of addressing those social norms or conditions that exacerbate health inequity.

Human rights provide a legal framework within which national laws, policies and services can be formulated and assessed, as well as an approach to the design of policies and programmes. The lack of clear international political commitment to the reproductive and sexual rights of HIV positive people presents a continual challenge.Citation73 Most international human rights documents pre-date the HIV epidemic and contain no specific reference to it, even as the majority of mechanisms responsible for monitoring governmental compliance with international legal and political obligations include HIV in their efforts. Some legally binding documents do address sexual and reproductive health, but governmental obligations to provide sexual and reproductive health services that meet the needs and aspirations of positive people are defined only in terms of governmental responsibility to provide sexual and reproductive health services to the population as a whole. It is incumbent upon governments worldwide to translate their international-level commitments to reproductive rights into national laws and policies that promote sexual and reproductive health, including for HIV positive people.

Most national constitutions have general non-discrimination provisions; some States have also enacted specific legislation to ensure that those living with HIV cannot be denied employment, health insurance, housing or other social benefits because of their HIV status. In addition, there are international policies that strengthen this non-discrimination norm with respect to HIV. For example, the Code of Practice issued by the International Labour Organization in no uncertain terms protects employees from job-related discrimination on the basis of their HIV status.Citation74 While there are of course many positive examples of how law and policy have been used to strengthen the access and use of sexual and reproductive health services, examples abound of laws and policies which, even if constructed for other reasons, have severely constricted the sexual and reproductive health and rights of positive people. Some of these harmful laws and policies are highlighted below.

Most egregious is when States have forcibly restricted the reproductive rights of positive people. For example, until recently, positive people in certain parts of India had no right to marry.Citation75 This is not only bad for public health but runs contrary to the obligations of governments to ensure that individuals have the right to marry.Citation76 In Poland, HIV infection is one of the few legally acceptable grounds for terminating a pregnancy and HIV positive people wanting to bear children are generally strongly counselled to have an abortion.Citation77 Forcible restrictions such as these can have serious negative consequences for HIV positive people, even if other services are made available for their benefit.

National law is the primary instrument by which a State acts and makes its public policy intentions and purposes known. In the area of health, a State's constitution may, for example, guarantee a right to health, or the special protection of maternity and childhood. National laws may establish a national health system and/or national health insurance. Some States enact reproductive health laws that mandate the provision of comprehensive health services for all; other States have laws restricting access to reproductive health technology. In the context of HIV and sexual and reproductive health, there are a number of areas of law and policy that have a direct bearing, including protection against discrimination and criminalisation of certain behaviours.

International human rights law does not allow for discrimination on the basis of HIV status. It strives to ensure that positive people enjoy the same rights as those who are not infected with HIV, and that all people are similarly enabled to fulfil their sexual and reproductive needs and aspirations. International legal and policy agreements clearly direct governments to provide appropriate and quality sexual and reproductive health information and services, to individuals (and couples) including adolescents, without discrimination. States must ensure that no laws, policies or practices discriminate in access to reproductive and sexual health information and services on the grounds of race, colour, sex, national or social origin, or other status. Other status includes HIV.Citation78

Yet, discrimination against people living with HIV (or people perceived to be living with HIV) remains pervasive. The negative effects of discrimination occur, for example, where health insurance tied to employment is withheld. The refusal to hire or the dismissal of a person because s/he is HIV positive violates their rights and compromises their ability not only to support themselves but also to access health care. Fear of loss of health insurance, without legal protection, may also create a negative incentive to find out or disclose HIV status. Laws to protect people against unlawful discrimination of all kinds based on HIV status are critical in human rights terms and for their beneficial effects on public health.

No example better demonstrates the negative effects on the health of positive people of government actions that exist outside the health sector than the criminalisation of certain behaviours. The impacts can be felt by a number of populations. For example:

Injection drug users

In many jurisdictions, not only is injecting drugs criminalised but services may require that the person's name and other personal information are made available to the police or another government agency, or the existence of needle exchange and other services designed for people who inject drugs are illegal. It is well known that HIV is spread when a contaminated needle is shared. Sterile syringe access programmes are proven interventions for the prevention of HIV and other blood-borne infections, and are considered “best practice” in HIV prevention. A number of states and municipalities have adopted ordinances which allow safe needle exchanges which are anonymous.Citation79 Legal and policy measures which ensure that people can access clean needles safely would go a long way towards ensuring that individuals feel comfortable seeking other health services without fear of arrest. Links between safe needle exchange, sexual and reproductive health and HIV services should be made.

Men who have sex with men

Laws which criminalise same-sex sexual activity are not only discriminatory but are known to impede HIV prevention and treatment programmes. In addition, the lack of information and education made available to people who engage in same-sex sexual activity in countries where these acts are illegal is bad for public health. Further, policies, whether official or not, whereby police and other authorities are permitted to harass and assault men who have sex with men with impunity may also drive them away from health services.Citation80 Policy should ensure that people who engage in same-sex sexual activity can access the sexual and reproductive health and HIV-related services they need safely.

Sex workers

Sex work is criminalised or illegal in most of the world and yet exists everywhere. This means that even if sexual and reproductive health and HIV-related services are made available to sex workers, they will not easily be used for fear that their name, HIV status and other personal information will be made available to the police or another agency and/or will result in their detention. Sex workers routinely face violence from their clients as well as the police, and in some places possession of a condom may be used by police as “proof” that a person is a sex worker. Decriminalisation of sex work and policies that prosecute violence perpetrated by police or clients, or promote proven public health standards regarding condom use and promotion of safer sex, would not only ameliorate the conditions which make sex workers particularly vulnerable to HIV infection but would facilitate their use of needed services.

Migrants

In a number of countries, e.g. China and Russia, an individual is entitled to obtain health care, including sexual and reproductive health services, only in his or her place of birth or official place of residence. Should an individual migrate even within the country, they would not be able to obtain these services. Undocumented migrants from Burma in Thailand are known to have high rates of HIV infection and to be unable to access needed health services.Citation81Citation82 Elimination of residency requirements and documentation to obtain health services would reduce health problems for this growing population group, whose labour supports many national economies.

Adolescents and young people

There are many constraints on access to and use of sexual and reproductive health services by adolescents and young people. These exist not only in law and policy but also in societal and cultural attitudes. Examples include requiring the consent of a parent or other adult for use of a service, restricting services only to those who are married, and the routine disclosure of test results or sexual and reproductive health concerns to parents or guardians. Factors related to gender and sexuality may compound these difficulties. UNAIDS and WHO urge that concrete attention be given to the needs of young people through the provision of confidential youth-friendly health services without legal and policy constraints.Citation83Citation84 Legal guarantees protecting the rights of adolescents to access health services without parental consent and to ensure that all personal information remains private, and disclosed only with their consent, will foster trust in the health care system and strengthen the use of sexual and reproductive health prevention and treatment services by young people.

Other issues to consider

Family law and the harmful cultural norms which accompany many of its provisions, e.g. in relation to marriage, divorce, child custody and inheritance, play a significant role in hindering access to and use of sexual and reproductive health services, particularly for people who are HIV positive. For example, widow inheritance, which treats widows as property to be inherited by a male relative of the husband who has died, bars them from inheriting property, and may mean they will be evicted from their land and home by in-laws and stripped of their possessions. Often it is their dead husband's brothers who make these claims, leaving the woman and her family destitute.Citation85 Such laws and practices are not only discriminatory but contribute to the risk of HIV infection.

Young people compare positive and negative HIV test results during an HIV awareness session with an HIV positive educator, Democratic Republic of Congo, 2006

Where the sexual and reproductive health of HIV positive women and men is concerned, the actions of a Ministry of Health are crucial, but so are those taken by other Ministries, including Education, Justice and Finance. Improved communication between relevant ministries and cross-sectoral familiarity with the laws and policies that affect sexual and reproductive health for people with HIV are necessary to achieve effective reforms. However, law reform takes time. While it may be relatively simple to identify the public health harm that, for example, the criminalisation of sex work creates, it can be difficult to propose reforms that law makers and other stakeholders can accept. Law reform and implementation is essentially a political process, often involving compromise; building a broad consensus among the police, health care workers, the community and policymakers is indispensable. The kinds of social change this implies can be a long, slow process requiring shifts in attitudes of affected populations and their communities.

Moreover, law and policy reform is but the first step: the finest laws and policies in the world will be of little value if they are not implemented. Governments must take active steps to put in place institutions, budgets and procedures that will enable effective implementation.

International human rights law recognises that States may not be able to implement in full all of the rights it has agreed it is obligated to ensure. Review and amendment of national laws and policies to ensure consistency with international human rights treaties is generally understood to be an obligation of immediate effect, even if resources to implement these commitments may need to happen progressively over time,Citation86 through continuous, deliberate and concrete steps towards the full realisation of rights. These steps should be commensurate with available resources and must demonstrate willingness to improve the situation over time. This has implications also for wealthier governments in terms of the technical and development assistance they offer.

Despite its shortcomings, the existing corpus of international human rights law affirms the necessity to promote and protect the sexual and reproductive health and rights of positive men and women. It remains for this to be better utilised in national and local level efforts to change harmful laws, policies and programmes and their impacts.Citation76

Conclusion