Abstract

All over the world HIV has been stigmatised, making it difficult for people living with HIV to access testing, treatment, care and counselling or even to act on a diagnosis or get advice and treatment, for fear of being judged. Prejudice in society has also often been reflected and reproduced by health care providers. A human rights approach, which positively incorporates sexual and reproductive rights, rather than a restricted medical view, is therefore essential for the achievement of true partnerships between health care providers and service users. This paper is about the experiences of HIV positive women and men in sexual and reproductive health services and HIV testing. It provides guidance not only on how things could and should be done but also on how they should not be done. It outlines the sexual and reproductive rights positive people consider crucial and gives examples of how these are being violated. It presents perceptions and implications of HIV testing and how health services can support people after a positive diagnosis. It analyses the importance of confidentiality, continuity of care, knowledge and information, and the role of support groups and home-based care. It calls on sexual and reproductive health services to address issues of stigma and discrimination when offering and carrying out HIV testing and counselling, and in providing treatment, care and support.

Résumé

Partout dans le monde, les personnes vivant avec le VIH souffrent de stigmatisation, ce qui entrave leur accès au dépistage, au traitement et aux soins, les empêche d'agir après le diagnostic et d'obtenir des conseils ou un traitement, par crainte d'être jugées. Le personnel sanitaire a souvent reproduit les préjugés de la société. Une approche des droits de l'homme, qui inclut positivement les droits génésiques, de préférence à une perspective médicale restreinte, est donc essentielle pour établir de véritables partenariats entre le personnel sanitaire et les patients. Cet article porte sur les expériences d'hommes et de femmes séropositifs dans les services de santé génésique et de dépistage du VIH. Il conseille non seulement sur la manière dont les choses peuvent et doivent être faites, mais aussi sur la manière dont il ne faut pas les faire. Il répertorie les droits génésiques jugés fondamentaux par les personnes séropositives et donne des exemples de violations. Il présente des conceptions et des conséquences du dépistage du VIH et montre comment les services de santé peuvent soutenir les patients après un diagnostic positif. Il analyse l'importance de la confidentialité, de la continuité des soins, de la connaissance et de l'information, et du rôle des groupes de soutien et des soins à domicile. Il demande aux services de santé génésique d'aborder les questions de stigmatisation et de discrimination quand ils proposent et assurent des programmes de conseil et dépistage du VIH, et dispensent un traitement, des soins et un soutien.

Resumen

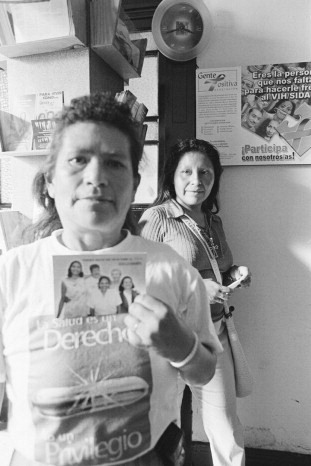

Por todo el mundo el VIH ha sido estigmatizado, lo cual dificulta que las personas que viven con VIH tengan acceso a pruebas, tratamiento, atención y consejería, o incluso que tomen medidas respecto al diagnóstico u obtengan consejos y tratamiento, por temor a ser juzgados. El prejuicio de la sociedad con frecuencia también ha sido reflejado y reproducido por los prestadores de servicios de salud. Por tanto, un enfoque de derechos humanos, que incorpore de manera positiva los derechos sexuales y reproductivos, en vez de una visión médica restringida, es esencial para lograr verdaderas alianzas entre los prestadores de servicios de salud y los usuarios. Este artículo trata sobre las experiencias de mujeres y hombres VIH-positivos con servicios de salud sexual y reproductiva y pruebas de VIH. Proporciona orientación no sólo respecto a cómo pueden y deben hacerse las cosas, sino también respecto a cómo no deben hacerse. Esboza los derechos sexuales y reproductivos que las personas seropositivas consideran cruciales y da ejemplos de cómo estos están siendo violados. Expone percepciones e implicaciones de las pruebas de VIH y cómo los servicios de salud pueden apoyar a las personas después de un diagnóstico positivo. Analiza la importancia de la confidencialidad, continuidad de la atención, conocimiento e información, y la función de los grupos de apoyo y la atención en el hogar. Hace un llamado a los servicios de salud sexual y reproductiva para que traten los problemas de estigma y discriminación al ofrecer y realizar pruebas y consejería de VIH, y al brindar tratamiento, atención y apoyo.

The International Community of Women Living with HIV/AIDS (ICW) is the only global network of HIV positive women. By 1992 when ICW was formed, HIV positive women had experienced enough indifference and lack of knowledge about the impact of HIV infection on women to galvanise them into founding their own support and advocacy network. The Global Network of People Living with HIV/AIDS (GNP+) is a global network for and by women and men with HIV/AIDS whose mission is to work to improve the quality of life of people living with HIV/AIDS. In all their work ICW and GNP+ have insisted that it is the HIV positive women, children and men who access (or not) and depend (or not) on health care services who can most convincingly evaluate whether a clinic and its health care providers are delivering the kind of HIV testing, care and treatment services they actually need. People living with HIV are also among the best judges of whether or not health services respect their sexual and reproductive health and rights and whether they are addressing issues of stigma and fear of discrimination effectively.

This paper presents the experiences of HIV positive women and men and draws partly on testimonies and research conducted by and with ICW members and staff, as well as from broader research and reports by and about people living with HIV and AIDS on sexual and reproductive health and rights and health services. The views, voices and experiences of HIV positive women and men presented here provide guidance not only on how things could and should be done but also how they should not be done. The aim of ICW and GNP+'s work and with this paper is to ensure that HIV positive women and men are able to access and benefit from quality services, including improving health care provider training, practice, policies and programmes.

All over the world HIV has been stigmatised and associated with shame, making it difficult for people to access HIV testing, treatment, care or counselling for fear of being judged. For marginalised groups such as sex workers, injection drug users, prisoners and men who have sex with men, this is especially difficult. Disapproving and poorly trained health care providers may treat some people with HIV as victims and others as dangerous people. A human rights approach, which positively incorporates sexual and reproductive rights for HIV positive women and men, rather than a restricted medical view, is therefore essential for the achievement of true partnerships between health care providers and service users.

Any discussion of sexual and reproductive rights for HIV positive women and men must also be analysed from the perspectives of gender and sexuality. A gender framework looks at the roles of women and men in society in relation to each other, and addresses the balance of power between them. A sexuality framework provides an understanding of sexual behaviour and relationships; in relation to men, for example, this relates to power, violence, homophobia and perceived gender roles. Moreover, HIV positive women and men may suffer stigma and discrimination not only because of their HIV status but also because of their status within societies; hence, the marginalisation experienced by many can have a multiplier effect in relation to stigma and discrimination. Injection drug users, for example, face discrimination not only within their communities but also from other HIV positive women and men.Citation1–3

A tension exists between the needs of people living with HIV and the economic and social realities in many developing countries, where health care services for the entire population are grossly under-resourced. Obviously, an investment in training of existing health care providers and an increase in their numbers in order to provide quality care for people living with HIV would also help to improve services for everyone needing health care, if it were done within an ethic of “care for all”. Idealistic or not, successfully addressing the sexual and reproductive health needs of women and men living with HIV necessitates deep changes in attitudes and behaviour. It also requires a recognition by governments, policymakers and health systems that health care workers are human too. They also need support to face these issues including HIV, in their own lives.

Sexual and reproductive rights of people living with HIV

No binding international and regional declarations on HIV and sexual and reproductive health and rights are specific to HIV positive women and men. However, a few have been developed by activists in order to provide a framework for their demands. One, the HIV Positive Young Women's Sexual and Reproductive Rights Charter,Footnote* was drawn up in 2004 as part of a young positive women's dialogue, organized by ICW in Swaziland. The charter declares that HIV positive women have the same rights as other women but also need access to HIV-specific information and services. Sexual rights as outlined in the charter include the right to say “no” to sex, to practise safer or protected sex, to decide who to have sex with without being judged, to start a new relationship, to be in control of our own sexuality, to decide on the type of sex practised, to sex education and information on sexual rights, to sexual pleasure and to be able to take legal action against sexual abuse or harassment.

Reproductive rights called for in the charter include the right to decide whether and when to conceive without being judged, to decide on the number and spacing of children, to abortion or sterilisation on demand (without requiring the consent of another person), to keep the baby, to education on labour, delivery and breastfeeding, to quality antenatal care (with or without being accompanied by a partner), to equal access to reproductive health care, regardless of social, economic or political status, to family planning information and decision-making over the type and use of contraception, to access HIV and sexually transmitted infection (STI) preventative methods such as microbicides when they become available, to safe delivery how and where women want, to assisted conception or artificial insemination, to feed the baby the way women want and to have accurate information about feeding options to be able to make an informed decision and to prevent mother-to-child transmission of HIV (PMTCT).

Women and HIV: The Barcelona Bill of Rights Footnote* was initiated at the International AIDS Conference in 2002 by Women at Barcelona and Mujeres Adelante with lead involvement by the International Women's AIDS Caucus of the International AIDS Society and ICW. It was the first charter to include HIV positive women in its design and focus, and incorporates a range of economic, social and political rights and specific sexual and reproductive rights. This Bill makes the link between inequality and women's vulnerability to HIV and highlights elements of rights of particular relevance to HIV positive women, including the right to live with dignity and equality, to bodily integrity, to health and health care, including treatment, to safety, security and freedom from fear of physical and sexual violence, to be free from stigma, discrimination, blame and denial, to human rights regardless of sexual orientation, to sexual autonomy and sexual pleasure, to equity in our families, to education and information and to economic independence.

Another charter that takes account of issues for both men and women living with HIV and AIDS on a national level is the Namibia HIV/AIDS Charter of Rights, drafted in 2000 by the AIDS Law Unit Legal Assistance Centre with the support of the United States Embassy, Windhoek and the Ford Foundation.Footnote† It calls for public measures to be adopted to protect persons living with HIV/AIDS, including children and adolescents, from discrimination in employment, housing, education, childcare and custody and the provision of medical, social and welfare services. In relation to sexual and reproductive health and rights, it says people living with HIV/AIDS are entitled to autonomy in decisions regarding marriage and reproductive health, including in decision-making on matters of family planning, and the right to take appropriate precautionary measures to prevent transmission of HIV. It calls for appropriate counselling and information regarding transmission of HIV to be made available to persons living with HIV/AIDS who wish to exercise the right to marry and/or found a family. It calls for quality health care, information and education for all children and adolescents, including those living with HIV/AIDS, on HIV/STI prevention and care tailored to age level and capacity, to enable them to deal positively and responsibly with their sexuality and rights. Lastly, as regards, education, it says that culturally appropriate formal and non-formal sex education programmes and information on HIV/AIDS should be accessible to enable people to make informed decisions about their life and sexual practices. Appropriate information regarding parent-to-child transmission, breastfeeding, treatment, nutrition, change of lifestyle and safer sex should also be freely available.

Emphasising that formal and informal sex education programmes and information on HIV/AIDS should be culturally appropriate can be a useful reminder that cultures differ in their approach to sexual and reproductive health. However, gender issues, the rights of young people and sexual rights must also be factored in to support a rights-based approach and avoid restricting the public health value of sex education and HIV-related programmes.

The Yogyakarta Principles on the Application of International Human Rights Law in relation to Sexual Orientation and Gender Identity,Footnote** just published by the International Commission of Jurists and the International Service for Human Rights, outline how international human rights apply in relation to sexual orientation and gender identity. The 29 principles include the right to equality and non-discrimination, the right to the highest attainable standard of health and the right to found a family. The application of these human rights principles to sexual orientation are especially important for HIV positive women and men in highly marginalised groups such as transgendered people, men who have sex with men, gay men and women, and male sex workers. A similar expert consultative process that applies human rights to the sexual and reproductive rights of HIV positive women and men would also be valuable, to define the obligations that States have in ensuring a safe and nurturing environment for HIV positive people.Citation4

Why sexual and reproductive health and rights matter for people living with HIV

“What do you do about fulfilling your sexual needs and desires when you keep getting gynaecological infections, as I do? What makes things worse is that these infections… make you feel totally undesirable. With treatment you have fewer episodes and things eventually become normal. You can have healthy, pleasurable, non-violent sexual activity, which is what we all desire.” (Rolake, Nigeria)Citation5

“I'd been to a hospital, and was told to have an IUD [intra-uterine device] fitted. Then, when they checked my medical file and learned that I've got HIV they said ‘Oh! This one is infected! The HIV-infected should not use it.’” Citation6

“I want very much to have a baby, but I want to be confident he or she will be okay in every sense… I want to make sure I am with the baby and the baby's father. Then if I fall sick the father will be there to take care of the baby. I have many fears around having a child, and at the moment I don't have a partner to support me in this choice. It's difficult because most men don't want to be with a woman who might become sick.” (Violeta, Bolivia)Citation5

HIV positive women and men have the right to make informed choices about their sexual lives and their reproductive lives, but there is no inherent right for anyone, including HIV positive people, to have pleasurable and satisfying sexual lives. However, HIV positive people are often expected not to have sex or only to have sex with other positive people. Sometimes, HIV positive people are afraid to have sex because they do not fully understand how to prevent HIV transmission. The notion of pleasure rarely comes into it, especially for women, because there are cultural barriers to discussing sex within either relationships or communities.

In order for HIV positive people to engage in sexual relationships that are satisfying and pleasurable, a transformation in how men and women approach sex is needed. The power differential between men and women must be addressed within a cultural context in order to transform gender norms and sexuality. Women must be given more power to take decisions about practices, partners, pleasure and procreation.Citation7 At the same time, men must be engaged in discussions on transforming how they understand and express their sexuality so that the sharing of power does not result in their disempowerment. Programmes have been successful in addressing the vulnerability that men experience when attempting to change how they perceive masculinity and take responsibility for their actions.Citation8Citation9

HIV positive men and women are doubly affected by the sexuality power differential, due to the extra vulnerability they face due to their HIV status. This differential may express itself even more when the couple is discordant, especially if it is the woman rather than the man who is HIV positive.

HIV positive women and men have the right to form families but are sometimes discouraged or barred from doing so. The desire to have children does not disappear because of one's HIV status; however, women and men do not often have access to appropriate information on their reproductive choices and can be pressured by family, health workers and communities to give up on the idea of having children.Citation10 Reproductive choices for HIV positive women and men should include but not be limited to adoption, assisted conception technologies such as sperm washing and donor insemination, and counselling on limiting the risks of natural insemination by monitoring the fertile period each month as well as appropriate post-natal care for mother and child. Additional research is required to determine whether or not HIV positive men who are on antiretroviral treatment with low viral loads present a significant risk when starting a pregnancy and whether or not their partners would benefit from either pre- or post-exposure prophylaxis and what effect, if any, this would have on fertility or on the child.

“ I have spoken to many global HIV experts who have all told me that I should simply take the risk and have unprotected sex with my partner during a period of three days when she is fertile. They tell me that the risk of HIV transmission is low because I have an undetectable viral load. Would they ever admit this in a public forum? Probably not. But after three months since we learned that my partner is pregnant, she is still HIV negative.” (HIV positive man, Europe)

HIV transmission occurs mainly through sexual relations. People often learn they have HIV through testing in sexual and reproductive health services, e.g. in antenatal care or sexually transmitted infection (STI) clinics. Having HIV transforms both people's experience of using these services and their experience of the life events, such as pregnancy and raising children, that bring them to these services to begin with.Citation11 Even if transmission occurs through a different route than sex, sexual and reproductive health remains essential for all HIV positive people.

Culturally normative ideas of who should and should not have sex and/or children result in poor, inappropriate services and information for all HIV positive people, but especially those who are more marginalised in society.Citation12 Violations of women's and men's sexual and reproductive rights increase their vulnerability to HIV infection, and their HIV positive status increases their vulnerability to sexual and reproductive rights violations. Violations directly impact on women and men's access to and experiences of HIV-related services and their ability to use information and services for their own well-being.Citation11

“A few of us have been infected with STIs, but it has been hard to go for treatment. Our husbands have refused to let us go to hospital because the service providers will ask us to call our husbands in, as they might have the infection too. Our husbands sometimes go to treat themselves secretly but they refuse to provide us money to go for treatment.” (ICW member, Tanzania)

Perceptions and implications of HIV testing

“I am a nurse. I worked in the health sector for seven, nearly eight years… When they found out at work, they sacked me. There was tremendous discrimination. My friends – so called – turned their backs on me.” (ICW member, Mexico)

If HIV positive women and men are not prepared for an HIV test, knowing or disclosing their status to others can have negative consequences. Women are often economically and socially dependent on men, which makes violence, mistreatment and abandonment a real and frightening prospect. If permission is needed from male partners, relatives or in-laws to access services, confidentiality is jeopardised and women's safety may be put at risk.Citation13–18

In considerations and recommendations around sexual and reproductive health and rights, the overwhelming impact of stigma, discrimination, isolation and unequal power relations must be remembered – between men and women, older and younger generations, people of different ethnicity, class and race, and between men and sexual minorities. We acknowledge the importance of self-empowerment for disadvantaged women, men and children in their daily struggle to survive and deal with the consequences of their HIV positive status.

Knowing their status allows people to protect others and themselves from infection and re-infection, to access appropriate care, treatment and support, and plan for the future. Yet of the estimated number of people living with HIV worldwide in 2005, only an estimated one in ten had been tested and knew that s/he carried the virus.Citation19 In many countries, unfortunately, HIV testing has been associated with dying, as many people are not tested until they show symptoms associated with AIDS and are very ill.

Before the advent of effective HIV treatment the benefits of a person learning their HIV status were primarily of prevention of transmission of infection to partners and infants rather than for the infected person themself. HIV testing methods have improved and provision of treatment is rapidly increasing, but quality services and access to treatment are still limited for the great majority of people in resource-poor countries. Testing services need to be scaled up and closely linked with treatment, support, care and prevention services. No one should be coerced into being tested, however, and the distinction between offering a test and pressuring someone to have it must never become blurred. The UNAIDS Reference Group on HIV and Human Rights recently affirmed people's rights in relation to testing in response to the new WHO policy on provider-initiated HIV testing and counselling that is currently being finalised.Citation20

The stigma of HIV can cause profound changes in sexual relationships and in familiesCitation13 and remains a significant barrier to testing. Stigma and discrimination on the part of family members, the community and health care providers are still widespread and can be life-threatening for people living with HIV. HIV positive women and men have faced loss of livelihood, ridicule, insults, harassment, exclusion from social functions, being forced to change residence, homelessness, refusal of entry into public places, physical threats, assault and even murder. Poverty, disempowerment, gender and sexual inequality also contribute to making decisions about HIV testing complex for both women and men. Even the act of being tested can be perceived as a lack of trust in a partner or a statement of the person's own unfaithfulness, let alone trying to act on advice once one's status is known.

As antiretroviral and other treatments become more widely available, the benefits of HIV testing have started to outweigh the disadvantages for more and more people, but the quality of treatment, advice and follow-up and access to a regular, lifelong supply remain real concerns. Even when treatment is available there are huge barriers to ensuring that women and men can use it to improve their health. For example, there are patients who must travel long distances and take days off from their work and home obligations. Those who do reach the clinic may face long queues, stock-outs of vital medications, out-of-date medications, lack of laboratory equipment, second- and third-line treatments, lack of advice and help with side effects, breaches in confidentiality when, for example, treatment is only available from one room, people taking the medication of other family members because they do not want to go through the lengthy and bureaucratic process of obtaining their own, bribes levied by health care staff, and being at the mercy of many of the people who work in the health care system, such as receptionists, nurses, doctors and pharmacists.Citation21Citation22

A positive diagnosis can damage young people's self-esteem and their ability to learn how to negotiate life needs. Young people are just beginning to try and understand their sexuality; scare campaigns which claim that sex is dangerous and leads to severe illness and death can result in fatalistic behaviour. In real life, people often have to evaluate their needs in complex contexts, including pressures not just to abstain from sex but also to decide whether to take part in unsafe or unwanted sex, as well as dealing with the desire for love, sexual pleasure, support and understanding.Citation12Citation15 Approaches to prevention that over-emphasise the importance of abstinence and fail to address sexuality through the provision of adequate information and counselling do not support personal, social and psychological development.

Men are expected to be self-reliant and invincible. As a result, many men still do not feel vulnerable to HIV infection or see any value in finding out more about HIV or sexuality. They face pressures in defending their masculinity by adhering to a sexual behaviour code that includes multiple partners, sexual prowess and sometimes violence. Testing HIV positive could change how men approach their lives as sexual beings, which may require changes in sexual self-perception and behaviour, and how they relate to their sexual partners.Citation2

Efforts to stem the pandemic have created an opportunity to challenge the way men relate to women and to each other. In South Africa, this can be seen in new support groups for HIV positive men that offer advice on health matters, HIV testing and counselling, sexual dysfunction and other services in an all-male milieu, run by HIV South Africa, the psychosocial support arm of the Perinatal HIV Research Unit, at Chris Hani Baragwanath Hospital in Soweto.Citation23 Like women living with HIV, positive men have experienced lack of support, illness and death as the consequences of non-disclosure and denial, and indeed as the consequence of disclosure.

HIV testing in sexual and reproductive health services that supports HIV positive people

“When I was pregnant and went for antenatal care, I was told to have a blood test. They did not tell me what the test was for. Every woman who came to the clinic had to have their blood tested. They did not explain at all what kind of test they were doing. I realised it was the AIDS test when I received the results.” Citation6

“Sangram [Maharastra, India] works with rural women because when people in rural areas are ill, chances are if they are men they will come and access the government health services, but if they are women they won't. The problem is that most women do not access services. The men get information; they also go to see the doctor much faster when they are ill compared with women who are ill. So the people who get referred to have an HIV test are basically the men in the family. The women, if they are getting tested first, it is only through the antenatal clinics who are compulsorily testing everyone who comes in the first trimester. So women actually getting tested is very little. And the women who are going for testing are only going because their men are positive and the doctor has suggested that the sexual partner should also be tested. We have seen very few women whose male partners are not infected actually going in for the test.” Citation12

The quality and form of HIV testing, treatment and care services can make sexual and reproductive rights violations of HIV positive women and men worse, for example, pressuring a woman to test with her partner, or disclose to her partner, even if that might exacerbate domestic violence. Moreover, inequalities in society and health care delivery interact with the stigma and discrimination surrounding HIV and AIDS, particularly for marginalised groups.Citation11 For example, prisoners may be forced to undergo HIV testing and because HIV is so highly stigmatised, prisoners with HIV are subject to discrimination and possibly violence and are therefore sometimes isolated from other inmates. HIV programmes in prisons must address stigma and discrimination, as well as provide strategies for prevention, including condoms and counselling.Citation24

According to the report AIDS Discrimination in Asia, the extent of coerced testing and the number of people tested without pre- or post-test counselling in the four countries studied is disturbing. Most diagnoses are given by a doctor, but busy doctors may not be the most able persons to provide appropriate counselling and support to somebody who has just received the news that they have a highly stigmatised, life-threatening condition. Positive people can be trained and employed widely to provide post-test counselling. Most people coerced into testing go on to experience discrimination within the very sector that tested them.Citation15

This is particularly worrying considering the fact that UNAIDS/WHO's policy on HIV testing since 2004 recommends not only patient-initiated testing and diagnostic testing where there are signs and symptoms of HIV-related illness, but also the routine offer of testing to all STI patients, all pregnant women in order to offer PMTCT treatment, and all health service settings where HIV is prevalent and antiretroviral treatment is available, e.g. injecting drug use treatment services, hospital emergency services and internal medicine hospital wards.Citation25

Where a person is supported to make an informed choice to be tested (opt-in), it gives them more power over their situation.Citation26 Although the UNAIDS/WHO policy is strong on the need for informed consent and the right to refuse, some providers are interpreting the policy as an “opt-out” policy, that is, if a person does not expressly say “no”, they can be tested for HIV. Networks of people living with HIV are concerned that unless people realise they can say no to an HIV test and have the confidence or power to make that choice, this strategy will take away their control over deciding and preparing themselves for HIV tests and the results.

“When I got pregnant at 16 I knew nothing. I didn't know I had a choice not to be tested. You can't just ‘opt-out’.” (ICW member, South Africa)

Services for testing are often located in sexual and reproductive health services. In antenatal clinics this allows a focus on the prevention of mother-to-child transmission and in STI clinics an ability to tackle the strong link between STIs and HIV. Antenatal clinics constitute an important place for reaching women and supporting their sexual and reproductive health when they may have limited access to other treatment and support services. However, if antenatal clinics force or pressure pregnant women to be tested, they jeopardise the likelihood that women will return for results or access services such as PMTCT, or indeed have their children tested.

Two examples of clinics that might serve as models for antenatal care, HIV testing and PMTCT are the Ndola Demonstration Project in Copperbelt Province, Zambia, and the Perinatal HIV Clinic at Chris Hani Baragwanath Hospital in Soweto, South Africa, which provide care and counselling services for HIV positive pregnant women. A third example are clinics for young people run by the Kara Counselling and Training Trust in Zambia.Citation18

The objectives of the PMTCT component of the Soweto-based project are to provide improved access to HIV counselling and testing services and establish the feasibility and acceptability of rapid on-site testing; implement the regimen for PMTCT of a single oral dose of nevirapine, self-administered by the mother at the onset of labour and a single dose administered to the baby within 72 hours of delivery; modify midwifery practices to minimise the risk of transmission, e.g. avoidance of rupture of membranes, episiotomies and oral suction of the newborn; and ensure safer infant feeding practices for HIV positive women. The Ndola project focuses on maternal nutrition as well as infant feeding, has introduced HIV counselling and testing into maternal and child health care as an ongoing service for pregnant women and their partners in antenatal, postnatal, family planning and curative services, and through referral from community members; and addresses the issue of stigma connected with not breastfeeding.Citation18

Kara Counselling and Training Trust centres, two freestanding and two attached to clinics, provide services for young people living with HIV, HIV testing and counselling, including pre-marital testing for young couples; training programmes in counselling skills and community home-based care and support; a vocational skills training programme and therapeutic support for people living with HIV/AIDS; HIV/AIDS outreach education programmes involving people living with HIV/AIDS; a residential training programme for orphaned and vulnerable girls who are socio-economically severely disadvantaged; and a hospice facility for chronically and terminally ill, socio-economically disadvantaged people.Citation18

Focusing only on women in antenatal clinics leaves women who are not pregnant and men out of the picture. In many countries, government health services now offer HIV counselling and testing within their clinics, hospitals and health centres. These services may be found in general hospitals, tuberculosis clinics, STI clinics, family planning services and abortion services.Citation18Citation27

Testing services for men who have sex with men, sex workers, injecting drugs users and other vulnerable groups are often and perhaps best located in services designed for those groups. In India, the Freedom Foundation gives comprehensive support to injection drug users in a national environment where follow-up services by government hospitals are almost non-existent and those provided by non-governmental organisations (NGOs) are inadequate as they stop after testing.Citation28 AIDS Concern in Hong Kong provides testing and counselling services in saunas to men who have sex with men and have used light-hearted messages to good effect. Amongst men who have sex with men in Hong Kong, the testing rate was relatively low at 15% in 2003. Reasons included lack of knowledge about HIV, fear and anxiety and inconvenience of testing facilities. Men who did decide to go for a test often anticipated discriminatory or negative reactions as well as having to conceal their real sexual identities.

The point is not just to come up with inventive ways of getting more people tested, possibly leaving people open to discrimination and abuse, but to ensure that they can then go on to improve and protect their health. Testing services for couples can provide opportunities to address the way in which they relate to each other sexually and deal with their diagnosis, whether positive or negative.Citation29 For people who are HIV negative testing should be seen as part of an ongoing prevention strategy. Support is especially important for those in HIV discordant relationships in order that they can employ prevention strategies for safer sex that match the changing needs of their relationships, including consistent condom use and safe pregnancy planning.Citation30

Counselling and support after a positive diagnosis

“I decided to have a check-up at one of the government hospitals. After the blood test, a nurse asked me to go into a room, and she said that I'll certainly die. She asked me if I know how much the virus spreads yearly, and she said that around 60% already died with AIDS. I was so scared… 60% is over half, so I will probably die in the next few years… my feeling was so bad.” Citation6

HIV positive people who participated in the Asia-Pacific Network of People Living with HIV/AIDS (APN+) study on discrimination in Asia referred to earlier, who described themselves as well-prepared to take an HIV test, were less likely to experience subsequent discrimination from health workers, families, employers, neighbours and landlords than those who felt coerced to be tested.Citation15

Those who provide HIV counselling, whether HIV positive or negative, should receive specific training, even if they are experienced health care workers. Counsellors may be professional health care workers, nurses, social workers or lay persons, or NGO and community-based organisation staff and volunteers, or simply community members, including people living with and affected by HIV/AIDS. Training in gender and sexuality, and an understanding of the specific gender and sexuality norms in their community, is also important.Citation31 In many countries, people infected with and affected by HIV and AIDS are providing HIV counselling; they may or may not disclose their own status during a counselling session but they may use their personal experience in the support they provide. In settings where the level of stigma is high, including among health professionals, people may prefer HIV positive peer counsellors because they are less likely to have judgemental attitudes and more likely to understand the consequences of violating confidentiality. People living with HIV can also play an important role in encouraging others to access HIV counselling, testing and follow-up services and educating them on healthy and positive living with HIV.Citation27

When people are involved in a supportive relationship, it is often better for them to receive the test results together, to get the full story at the same time, help each other to cope with the test results, whether they are the same or different, and support each other during counselling. They can be encouraged to plan together for the future of their relationship, e.g. in sexual decision-making, increasing condom use and practising safer sex, reducing the risk of transmission if they are sero-discordant, making plans for any children and share feelings of upset, anger or blame with the counsellor's support.Citation27 However, individuals should have access to HIV testing and counselling in their own right, whether or not they are in a relationship, and partner disclosure must remain voluntary with appropriate support and counselling.Citation7,32 The AIDS Information Centres in Uganda give counselling on a one-to-one basis, but with the person's consent they also involve the partner and/or family members.Citation33

People have many different needs after a positive HIV test. Money and medicines are important, but not everything. Ongoing counselling and post-test support and services are not just for people who are seriously ill. People with HIV may be physically well but depression is experienced by a great many, up to 44% according to WHO. Post-test support and services can be provided by many different types of groups, including NGOs, faith-based groups, groups of people living with HIV and AIDS, health services and employers. However, it is important that there are effective referral systems to ensure continuity of care and support.Citation27

HIV success stories in Brazil and Thailand have been based partly on open acknowledgement and discussion of high risk sexual behaviour and practices, openness about sexual orientation and policies for making sex safer, e.g. in sex work, often initiated by or with the active involvement of people living with HIV, and with commitment at the highest political levels enabling this. Positive people continue to be sexual beings even after a diagnosis of HIV and their feelings and needs related to sexual relationships can change over time. Sexual dysfunction in people living with HIV may be quite common due, for example, to side effects from antiretroviral therapy and depression. This needs to be highlighted more in sexual and reproductive health and treatment adherence services.Citation34

“At the time of my diagnosis, I was in a good relationship with someone else and although we had always had protected sex I could no longer have sex with him. I felt dirty, disgusting, used and as far from sexy as humanly possible. The relationship ended and I spent the next four years celibate.” (ICW member, Zimbabwe)

Health workers should encourage, but not pressure, women and men to talk about sex, sexual health, pregnancy and parenthood and should themselves feel comfortable discussing these issues. They need to recognise that women and men may want counselling that is about enjoying sex as a positive person, developing the skills and confidence to say no to sexual involvement or change the kind of sex they have.

In parts of sub-Saharan Africa, post-test clubs for both positive and negative people have been an effective way to share issues and concerns with peers, as demonstrated by the AIDS Support Organisation (TASO) in Uganda. A whole range of diverse support can be offered – for example, groups supported by CARE Cambodia provide para-legal assistance. AIDS Access in Thailand trains groups of people living with HIV and AIDS in hospitals to help ensure access and adherence to antiretroviral treatment, through peer-to-peer counselling, and also to promote the concept of “positive prevention”.Citation28 The Liverpool Voluntary Counselling and Testing Project in Kenya addresses HIV in their gender-based violence services. Counsellor training looks at gender inequalities in relationships and how to discuss women's experience of power in sexual relations so as to provide those who come for testing with strategies for negotiation of safer sex as well as sexual health and HIV clinical care.Citation35

People with HIV have always had an essential role to play in preventing new infections. However, prevention strategies often fail to address the distinct prevention needs of people with HIV, and to acknowledge their significant efforts to avoid infecting others. Strategies for positive prevention should aim to support people with HIV to protect their sexual health, get treatment for existing STIs, avoid repeat infection and maintain health and nutrition – as well as avoid passing HIV to others.Citation36 From an epidemiological and public health perspective, an important group to address with HIV/STI prevention strategies are people already living with HIV. This is particularly the case in low prevalence settings, where the epidemic is contained in certain key populations. Positive prevention is also important because people living with HIV have the right to live well with HIV, which includes having a healthy sex life. It is also important to encourage people who are HIV negative or untested to understand that they are equally responsible for protecting themselves and others from HIV and STIs.

Many people need social and psychological support to cope with their diagnosis and deal with the life changes arising from it. From a human rights perspective, people with HIV have a right to know their HIV status but also the right not to be tested. Practising safer sex with all partners and always using clean needles are key prevention strategies. Many people with HIV, however, are not able to obtain condoms or clean needles. The target in positive prevention should be 100% access to and use of male and female condoms and lubricants and no needle-sharing at all for people living with HIV and AIDS.Citation37 A key issue for HIV positive women and men is how to successfully and safely negotiate condom use with a partner. There is also a role for discussions around pleasure and alternative forms of sexual expression aside from penetration, including mutual masturbation, frottage, oral sex, erotic massage and exchanging sexual thoughts and desires.

Prevention for key populations, e.g. men who have sex with men, transsexuals, sex workers or injection drug users, should use messages that

build on people's strengths rather than blaming or condemning sexual behaviour, sex work or drug use. In Ecuador, the International HIV/AIDS Alliance supported capacity-building for services for people with HIV in three cities, including for sexual and reproductive health clinics, sex worker organisations, government STI clinics, community-based organisations of people living with HIV/AIDS, gay, lesbian and transvestite organisations, counselling and testing centres and local government. These organisations then supported community mobilisation, distribution of condoms and lubricants, improving the quality of services, information and education, and influencing policy in order to strengthen people's ability to have safer sex.Citation37The need for ongoing counselling, support and public health campaigns can be illustrated by trends in HIV positive gay men in Europe and North America. After the successful reduction in the incidence of HIV transmission in the 1980–90s in gay communities, through interventions led by gay men, many of whom were HIV positive, the introduction of antiretroviral treatment in 1996 was a watershed for HIV prevention. The incidence of HIV and STIs is again rising among gay men, especially in large urban centres. Reasons for this include “prevention fatigue” and a misunderstanding that taking antiretrovirals is less of a hassle than using condoms. New and innovative approaches for reaching both younger and older gay men with prevention messages are again needed.Citation38Citation39

Services that support positive sexual and reproductive health

“If you start using milk powder everyone will know you must be HIV positive. If you demand condom use to stop repeated exposure, he will either hit you or just go off and have sex somewhere else anyway and likely bring back other infections. So you just go on having unprotected sex and breastfeeding, even though you know you are doing exactly what they tell you you mustn't do…” (ICW member, South Africa)

“In Swaziland there are no dedicated sexual and reproductive health services to address the specific needs of HIV positive women. The only available service is for prevention of mother-to-child transmission. Cervical cancer is very common among HIV positive women, and yet in Swaziland there is no effort made to encourage us to go for pap smears. The incredibly high prevalence rate of HIV in my country means this service would be highly appreciated. It would facilitate early diagnosis and immediate intervention, potentially saving many women's lives.” (Gcebile, Swaziland)Citation5

“Regarding the reproductive health of HIV positive women in the Ukraine, I have three wishes: availability of medications to prevent mother-to-child transmission; universal availability of viral load tests for HIV positive pregnant women; and universal availability of caesareans for HIV positive women who choose them. I would also like to see family planning organizations running training programmes for midwives and obstetricians as well as developing and distributing information materials, and lobbying for new standards of treatment.” (Tanya, Ukraine)Citation5

“Family planning clinics in Nigeria should subsidize the female condom, as it gives women the power to take more control over their sexual lives. They should begin to talk about sexuality and family planning for positive women.” (Rolake, Nigeria)Citation5

If counselling and testing are provided alongside services for TB, family planning, nutrition support, post-exposure prophylaxis, emergency contraception, STIs, and maternal and child health, it can increase the number of people who seek testing, by decreasing stigma.Citation40 Links and referral between free-standing testing sites and other services can provide a more comprehensive package of care, while providing education on positive living and early identification and management of HIV-related and other health problems.

Because injecting drug users have socially engendered needs related to their legal, health and employment status, services require a tailored approach. This includes counselling on harm reduction strategies (for example, advice on substitution therapy), messages on sexual and reproductive health, including positive prevention, STI management and the risk of hepatitis B and C and other blood-borne viruses.Citation3,41

When the prevalence of HIV in communities is high (above 10%) it is more difficult to provide separate services for people with HIV. Instead, all health care facilities need to be geared to the needs of positive people, e.g. extra surveillance for ano-genital cancers and STIs, including HPV vaccination where possible, and specific advice and support for conception, pregnancy and parenthood and contraception.Citation12 Specialist and academic centres may be in a position to develop the expertise needed, which can then be incorporated into training programmes for front-line staff, so that HIV positive people have access to care where they live or work rather than having to travel to specialist centres. But specialised HIV care services that combine outreach and are linked to general and other sexual and reproductive health services (and vice versa) can ensure better access, higher quality and improved follow-up, and some services need to be tailored for particularly vulnerable, stigmatised or hard-to-reach groups.

Confidentiality

“It happened that personnel at the health care centre, a nurse, said somewhere around my neighbourhood that… ‘Yes, yes, this girl (meaning myself) really has HIV’.” 6

“In my case, the thing that is stigmatised is going to fetch the milk each and every week. It is collected from a particular room and if you go to that room they know you are HIV positive.” (ICW member, South Africa)

HIV positive women and men want to control to whom and when their HIV status is disclosed, though this is not always possible. For example, in many countries where HIV is prevalent, women who are not breastfeeding are assumed to have HIV.Citation42 Someone may notice that a person has medication in the fridge or is taking it at certain times every day, that they have to make trips to the hospital regularly or belong to a support group. Weight loss because of AIDS or redistribution of weight as a side effect of certain antiretroviral drugs are also telltale signs. Having to ask relatives for permission, time or money to access services may force an admission of the reason why. And far too often health care workers and auxiliary staff may gossip or say or do something that informs others, on purpose or inadvertently.

Non-disclosure of HIV status may be against the law or contrary to policy in certain circumstances; and disclosure or an HIV test may be a requirement for many jobs, research trials, visa and insurance applications. In many antiretroviral programmes, disclosure to a family member is a prerequisite for accessing treatment. There are cases where women and men pay strangers to collect drugs for them, in order to avoid disclosing their status to family membersCitation32 or where they are pressured to hand over or share their treatment with other family members who may want to avoid community members and health workers finding out their status when they access services.

A model of how to protect confidentiality can be found in Free State, South Africa, where a mining company health service provides preventative therapy, early identification and treatment of HIV-related diseases, and counselling and support for HIV positive patients. They have a clinic name that was not explicitly linked to HIV, hold the clinic in the same outpatient department as other specialised clinics, keep clinic records secure and separate from other hospital files and store information in a secure, password-protected database.Citation43

Involving HIV positive women and men and young people in service design and delivery can help to resolve many of the difficulties surrounding confidentiality. Health centres can develop and enforce a code of conduct that includes the right of patient confidentiality, and peer and other counsellors can help positive people to find ways of preventing breaches of confidentiality and handle disclosure well when it takes place. It should also be possible to lodge a complaint if confidentiality is broken by health care providers.

Continuity of care

Lack of continuity of care can lead to missed opportunities to provide sexual and reproductive health care, including management of STIs and other reproductive tract infections and advice on the impact of antiretrovirals on sexual and reproductive life. Opportunities may also be missed to check and provide support and care for opportunistic infections, TB, infertility or sexual dysfunction, or to carry out screening such as an HPV test and Pap smears. In India and Kenya, HIV positive patients said they were often not referred but had to proactively seek out different types of care and providers themselves.Citation12

Integration of education and counselling on sexuality and STI/HIV into family planning and mother and child health services is increasingly common and successful in Africa and Latin America. However, antiretrovirals are generally only provided in high prevalence areas through antenatal and delivery care for PMTCTCitation44 and more recently with antiretroviral roll-out through specialist HIV centres. Diagnosis and treatment of STIs and opportunistic infection, condom promotion, support for survivors of gender-based violence and psychological and nutritional support are still extremely weak in reproductive health care settings in southern Africa.Citation45

Ineffective systems outside the health service can also lead to critical delays in providing services. In South Africa, for example, the government aims to provide a comprehensive package of care for sexual assault survivors, including counselling and testing for HIV, pregnancy and STIs, and antiretroviral post-exposure prophylaxis. However, delays in accessing post-exposure prophylaxis caused by the public justice system and lack of training for service providers have created significant obstacles.Citation46

Lack of continuity of care for HIV positive mothers can reverse the positive impact of PMTCT programmes, in that many babies born HIV negative thanks to treatment are then being infected later, particularly if a mother switches between bottle feeding and breast-feeding during a baby's first few months. Of three PMTCT sites studied in South Africa, the site in the poorest area had almost double the vertical transmission rate of the best resourced site after nine months.Citation47 Poorer women are also more likely to be caught between the stigma of not breastfeeding, stock-outs of formula milk powder in health centres and inappropriate and inaccurate advice from health workers, as was found in a study in rural Tanzania.Citation48

HIV positive women who are injection drug users (heroin and other opiates) are often advised to stop using drugs altogether while pregnant without any type of support. Instead, what they need is access to substitution therapy with methadone during pregnancy and PMTCT. Heroin is short-acting, so its use is associated with recurrent degrees of withdrawal. This can cause muscle spasm in different parts of the body, resulting in a number of symptoms, including diarrhoea and muscle cramps. During pregnancy its use can cause miscarriage and premature delivery and can restrict fetal growth. Methadone does not cause these effects so during pregnancy it is important that women using heroin are prescribed methadone as a substitute. Although substitution therapy is on the WHO List of Essential Medicines, many countries are reluctant to implement this advice. Advocacy is needed to ensure that PMTCT programmes in countries where injection drug use is an important source of HIV infection in women provide substitution drugs for those who are drug-dependent.Citation49

Another aspect of continuity of care has to do with treating a whole family affected by HIV rather than just an individual woman or man. A growing number of programmes are attempting to address this problem by providing not only PMTCT but also ongoing treatment for mothers and if needed to their partner, to encourage joint family support.Citation50 This helps to create a conducive environment in which to focus on women and men's sexual and reproductive health concerns, including the concerns of sero-discordant couples.

The PMTCT-Plus Initiative serves as an excellent model in this regard. This initiative, formed in 2001, involves the integration of reproductive health services into HIV care and treatment programmes for HIV positive women and their positive children and partners, emphasising the long-term follow-up of families and the provision of comprehensive care across the spectrum of HIV-related illness. While HIV care and treatment programmes in resource-limited settings may not be able to integrate all reproductive health services into a single service delivery model, there is a clear need to include basic reproductive health services, such as contraception, condoms and abortion. The Initiative was shaped by the growing recognition that early PMTCT programmes often provided minimal or no care to HIV positive mothers, missing an obvious opportunity to promote women's health and prolong their lives, repeating similar shortcomings found in maternal and child health programmes in the past. As of November 2004, PMTCT-Plus programmes had been set up in 13 sites in eight African countries and in Thailand.Citation51

The interface between health services and peer support is another form of continuity of care, which over-stretched clinics appreciate. Mothers2Mothers (M2M) is an innovative, community-based education and mentoring programme for HIV positive pregnant women and new mothers in South Africa. M2M trains and employs new mothers who have themselves benefited from services to become “mentor mothers”, who comprise a team of facility-based, grassroots caregivers and educators. Mentor mothers have become an increasingly integral element of clinical PMTCT care; they focus medical attention on a mother's physiological, psychological, emotional, social and spiritual needs. M2M services include regular support groups, formal and informal individual counselling, help with issues of disclosure and stigma, comprehensive education sessions about HIV/AIDS, PMTCT and personal and new-baby health, and daily gatherings for nutritious lunches and nutritional education. They currently operate 65 sites in five provinces in South Africa, with plans to expand to three times more sites, and have forged strategic partnerships with organisations in Ethiopia and Botswana to implement a national model in those countries. They also have plans to launch services in as many as seven other countries in southern Africa.Citation52

Knowledge, skills and information

“With doctors it is hard to say: ‘It is my body. I know what I am feeling and what is right for me’.” (ICW member, South Africa)

“In hospitals, if you don't know anything, you are lost, because they are so short-staffed. I make sure I know what I have and what I need, for example, this tablet for this STI.” (ICW member, South Africa)

Knowledge about their health problems and rights can put HIV positive women and men in a much stronger position for accessing needed health care. Yet many women and men, both positive and negative, often lack knowledge of HIV, AIDS and sexual and reproductive health, and the relationship between them. In Kenya and Zambia, women who were pregnant reported refusing to take or returning drugs they had been given for treatment in the mistaken belief that the drugs would harm the fetus.Citation53

Support groups and civil society organisations can play a vital role in providing relevant, accessible, non-biased, comprehensive information in local languages and for those who cannot read. After WHO announced its “3x5” initiative, an International HIV Treatment Preparedness Summit took place in Cape Town in 2003 with participants from 67 countries, and the International Treatment Preparedness Coalition, a global consortium of people living with HIV and treatment activists, was set up. The report of the summit says:

“Treatment literacy must stem from good science… Advocates must learn and understand the science of HIV in order to be effective and develop sound policy. Treatment literacy for both health care providers and people with HIV is essential if we expect treatment to be effective. Information is as important as medicine. Without good treatment education, we cannot effectively manage side effects or expect good adherence to therapy. Treatment literacy for the government and the public is also essential. Knowledge that effective treatments exist will help alleviate the fear and stigma associated with AIDS and encourage people to learn the facts about HIV and to utilize counseling, testing and care. Treatment education programs must be targeted and adapted to meet the cultural and educational needs of the community.” Citation54

Many positive people's groups and organisations are now teaching treatment literacy, and sexual and reproductive health and rights, skills building, assertiveness training, communication and self-care could also be included in such work.

Stigma and discrimination

“Most of the HIV positive women in Nepal are widowed and/or abandoned by their family. This means they have a lot to worry about apart from their sexual and reproductive health. Staying alive and keeping safe are their main concerns. In my case, two years after my diagnosis I married an HIV positive man. I am lucky that my husband supports and cooperates with me and that we are able to discuss sexual and reproductive health issues. But sadly we don't have many choices available to us.” (Asha, Nepal)Citation5

“I went to the hospital for treatment of another disease, but as they knew I had HIV from the history file, the doctor refused to treat me.” Citation15

“When Mike was hospitalized, doctors wanted to draw blood from him so they could do an HIV test. He already knew that he was HIV positive, so he refused, but the hospital staff managed to get a sample of his blood after telling him they were just going to take his blood pressure. Mike and his wife Anna endured humiliation when the entire hospital found out about his HIV status.” Citation15

“The doctor said: ‘Why do you want to keep this [uterus]? Cut it out and throw it away!” Citation6

Judgemental attitudes and fear of the virus abound in health services and in communities. In the qualitative study referred to earlier by APN+ of discrimination against positive people in four Asian countries, 764 HIV positive men and women were interviewed. 80% reported experiencing some form of discrimination, including 54% within the health sector, often commencing at the point of testing, 31% in the community, 18% within the family and 18% in the workplace, including the sexual and reproductive rights violations listed in Table 1. In Indonesia, women were twice as likely to experience discrimination as men. In the health system, 15% of respondents were refused treatment or care and 17% experienced delay in service provision. Some respondents (9%) were persuaded or advised not to access health care services, often by health care workers, while 9% said they were forced to pay additional charges because of their HIV status. 19% of men and 7% of women had been denied medical treatment for a range of other health problems during the previous 12 months. Those who were coerced into having an HIV test experienced greater discrimination.Citation15

Similarly, in 2005 HIV positive women in Namibia reported being told they could not access antiretrovirals unless they accepted injectable contraceptionCitation22 and in a workshop in Lesotho, HIV positive women reported being told they had to use long-term contraception in order to participate in a three-year “trial” of antiretroviral treatment.Citation55

Mistreatment and discrimination make anyone feel uncomfortable but those who are already marginalised or excluded from mainstream society, who are often the most vulnerable, get the least attention, e.g. street children and young male sex workers. Discrimination on the part of health care providers is particularly difficult to cope with.Citation56 Sex workers may fear that accessing services will reveal their status to other sex workers or clients. Even within HIV support groups and NGOs discrimination may be expressed if a woman is found to be a sex worker.Citation6

The sexual and reproductive health and rights of HIV positive men who have sex with men are often ignored in discussions of sexual and reproductive rights, particularly when it is erroneously claimed on the one hand that “homosexuality does not exist in our country” while at the same time it is criminalised. In addition, the fact that many HIV positive men who have sex with men may also be fathers, may suffer from infertility, STIs, sexual dysfunction or genital cancers is all but invisible in terms of public health responses.

Men at special risk of HIV infection include men who have sex with men, injection drug users (80% of whom are men), migrants and refugees, prisoners, male sex workers, the uniformed forces and street children. Men are generally socialised to be self-reliant, sexually dominant, have multiple partners and be omniscient about sex.Citation1 Men and boys who do not fit these norms are highly stigmatised in many societies, and discriminatory treatment ranging from sexual dominance to violence may result.

In Senegal, the lives of many men who have sex with men are characterised by violence and rejection.Citation57 In Africa, there are over 10 million street children, most of them boys. Many are vulnerable to prostitution and sexual exploitation. Many young men turn to sex work to pay for drugs–studies in Argentina, Brazil, and Canada have shown that at least a third of drug users of both sexes had exchanged sex for drugs at least once; some also turn to crime to pay for a drug habit. If they end up in jail they face the danger of contracting HIV there. Drug injection and sex between men, including rape, are common in prisons, placing inmates of all ages at risk of HIV. Alcohol also has a great impact on the epidemic. Its consumption in large quantities, common among young men and increasingly among women across most parts of the world, leads to many high-risk activities.

Soldiers are isolated from women for long periods, which can result in relationships with other men, paying for sex and having many sexual partners. Soldiers, within their hyper-masculinised and violent environments, may participate in acts of rape in war, use drugs and tend to have higher rates of HIV/STIs than men in the general population.

Men and boys are central to the course of the HIV epidemic, yet often they remain peripheral in the response to HIV.Citation58 Programmes have demonstrated that involving men can lead to sustainable positive change in sexual behaviour and reduction of violence against women.Citation59 Similar principles should be applied to changing stigmatising and discriminating behaviours toward HIV positive men and women.

Discrimination can take place between HIV positive people as well. HIV support groups, like other community groups and organisations, may fail to adequately address age, gender and other types of discrimination in their own ranks.Citation6 This is true of single sex and mixed sex groups. For example, sex workers, injecting drug users or men who have sex with men can find it particularly difficult to access support due to judgemental attitudes towards them on the part of other HIV positive people. The Collaborative Fund for HIV Treatment Preparedness has been noted for the extent of open and candid discussion of common concerns, contrasting experiences and potential conflicts in their regional meetings. Yet the report of their March 2003 Commonwealth of Independent States/Baltic States regional meeting noted that existing tensions between current and former drug users and gay men, and perceptions of discrimination against active drug users within organisations of people living with AIDS in the region were being addressed only for the first time.Citation41

Should HIV transmission be criminalised?

“I was sexually abused by my ex-partner and eventually he infected me with this terrible virus on purpose.” (Josephine, Kenya/Netherlands)Citation5

In a number of countries, people with HIV and AIDS can be legally charged for knowingly transmitting or exposing a sexual partner to HIV. In Europe, for example, 14 countries have enacted or amended legislation to deal specifically with transmission of HIV and/or other sexually transmitted infections. In 16 countries, under these and other existing laws, only actual transmission was considered punishable, while in an additional 16 countries exposing another person to the risk of transmission was also considered punishable.Citation60 In 21 countries, at least one person has been prosecuted and across Europe, there have been at least 130 convictions. Austria, Sweden and Switzerland are responsible for more than 60% of all convictions, and have each prosecuted more than 30 people.Citation61

The bulk of convictions reported were apparently applied to alleged transmission during consensual sex. However, there have also been cases where HIV positive people have been found guilty of transmitting the virus even though they did not know their status at the time. The Supreme Court of California in the USA has determined that a history of “risky sexual behaviour” is enough to indicate culpability, thereby further complicating criminalisation issues.Citation62

Criminalisation of HIV transmission raises many questions. Do such laws actually deter behaviour that results in or threatens HIV transmission, that is, do they achieve valid prevention goals? Might more intensive public health education and measures achieve prevention goals more effectively than criminal law, and is HIV-specific legislation in this area ever warranted?Citation60 If an HIV positive woman who is unable to negotiate safer sex then infects a partner, should she be blamed and criminalised?

There are ethical questions too: if infection is acquired during voluntary, consensual sexual intercourse, is it a case of an HIV positive person doing harm to another or of an HIV negative person doing harm to him/herself? The answer may be different for partners in a long-term relationship as opposed to people who do not know each other well, but whether or not HIV status is known or disclosed,Citation63 the ethical question is whether or not the responsibility for safer sex is a shared one. In spite of the different answers possible to this question, laws and policies have been made by a number of countries to criminalise those who infect others with HIV, to ban marriage to an HIV positive person and to forbid the promotion of condoms to those who are not married.Citation64

The role of support groups

“At first, we went into our advocacy work with our faces covered because it was too dangerous to let anyone see us… In the end, though, we started to disclose and to give our names out.”Citation65

“The MSM [men who have sex with men] programme started… in response to MSM clients requesting the formation of a support group around issues of sexual orientation and sexual health. As such, a support group was formed that ran for six months in 2004, as a precursor to the MSM programme. A total of 14 MSM (mostly male commercial sex workers) met twice per month with an experienced (and openly gay) facilitator. Topics covered by the support group included identity, labelling, HIV and sexual health, condom negotiation, access to services, vulnerability and disclosure.” Citation66

Support groups have been around since the beginning of the epidemic, starting in the United States. The need for self-determination that began with the Denver Principles led to the formation of international networks of women and men living with HIV and eventually the policy of greater involvement of people living with HIV (GIPA).Citation38 When HIV positive people join a support group they become part of a larger reality, one which offers the possibility of

peer support, but also of building collective strength and lessening isolation. Support groups are more than useful adjuncts to more formal health care at any level and play an important role for HIV positive people. They can play an advocacy role and influence government policy on HIV and AIDS.

Support groups and organisations help women and men come to terms with being HIV positive, deal with decisions about disclosure, think about their sexual behaviour, explore care and treatment issues, articulate their experiences, realise that they are not alone, share survival strategies – as well as providing vital emotional support.Citation67 There is often less stigma associated with HIV in communities that have good counselling services and active self-help support groups.Citation68 Testing and treatment facilities should link up with support groups or encourage new ones to form so that those who test positive can join a group and get support from the start.

Support groups have changed as the epidemic has changed. In North America and Europe, for example, support groups were a lifeline for hundreds of gay men who were dying, stigmatised and alone at the beginning of the epidemic. Adequate services did not exist, so support groups became AIDS service providers and advocacy organisations. With the advent of treatment, support groups have adapted to new needs. Today, in Europe, organisations that began as support groups are now full service organisations for diverse groups such as gay men, women, immigrants and people who use drugs. In the Netherlands, recent lack of attention to their needs has led to the creation of a splinter group of gay men, “Poz and Proud”, that strives to ensure that the burden of prevention is shared equally between positive and negative men and offers a safe space for HIV positive gay men to talk about sexuality, discordant relationships and prevention options.Citation69 HIV positive women too have set up women-only groups to discuss shared concerns that are often not covered in mixed-sex groups.

For people living in poverty in particular, support groups may be a lifeline. Poverty prevents millions of HIV positive people knowing about or being able to access or use treatment and care services. At a workshop on “Women, Children and Families: Treatment Preparedness and Advocacy” in Uganda in November 2005, activists from across sub-Saharan Africa raised concerns that women were sharing their medication with other family members, sometimes through coercion, sometimes due to guilt, and putting themselves at risk. This problem is heightened when men use their women partners as a proxy to avoid having to be tested themselves. Many HIV positive women have been driven to sell their antiretrovirals in order to feed their families:

“A 44-year-old woman in rural Tanzania who was on antiretroviral treatment had to sell them in order to get some money to take care of the grandchildren living with her in her small home. All of her 13 children had died from AIDS-related illnesses. Of her grandchildren, some are street children, especially the boys, and some of the girls practice prostitution, so they sometimes disappear for months and then come back. Of her 14 grandchildren, she takes care of three under the age of five. She thinks eight of the children may be HIV positive as they are not that well. She was only able to provide one meal a day in the afternoon, which consisted of porridge with salt, as that is what she could afford. After she had been on treatment for two months, she started selling her antiretrovirals to HIV positive people who did not want to get medications at the clinic due to stigma. When she joined a group for people living with HIV approximately a year later, they counselled her to stop selling her antiretrovirals and instead to go back on treatment. The group sometimes provides her with food and other important needs.” Citation70

This important role cannot be underestimated. There are numerous examples of women's self-help support groups and networks which have been set up at local, national and international levels; the Mama's Club, which meets at TASO in Uganda and offers peer support for young HIV positive mothers is one example.Citation71 There are far fewer examples of such networks run by or for men. This places a greater burden of care and support onto women, both within the family and in society.Citation12

Home- and community-based care and support