Abstract

A trained health service workforce is critical to ensuring good quality service delivery to people with HIV. There is only limited documented information on the challenges and constraints facing health care providers in meeting the sexual and reproductive health needs of HIV positive women and men. This paper reviews information on providers' attitudes, motivation and level of preparedness in addressing the sexual and reproductive health needs of people living with HIV in the context of the human resources crisis and emerging treatment and prevention strategies. There is a need for significant investment in improving the health infrastructure and providers' ability to take universal precautions against infection in health care settings. Additionally, there is need for comprehensive and appropriate training for health care providers to build their capacity to meet the requirements and expectations of different sub-populations of HIV positive people. This includes not only physicians but also nurses and midwives, who are the primary caregivers for most of the population in many resource-poor settings. Supportive and knowledgeable providers are crucial for helping HIV positive people seek and adhere to treatment, prevent sexually transmitted infections, unintended pregnancies and vertical transmission of HIV and support positive living free from stigma and discrimination. Providers, some of whom may themselves be HIV positive, can make an important difference, especially if they are supported in their working conditions, are knowledgeable about HIV and sexual and reproductive health and have the skills to provide good quality care.

Résumé

Un personnel sanitaire formé est essentiel pour garantir des prestations de qualité aux personnes vivant avec le VIH. On ne dispose que d'informations limitées sur les difficultés que rencontrent les agents de santé pour répondre aux besoins de santé génésique des femmes et des hommes séropositifs. Cet article passe en revue des informations sur les attitudes, la motivation et le niveau de préparation des prestataires pour répondre aux besoins de santé génésique des personnes séropositives dans le contexte de la crise des ressources humaines et des stratégies émergentes de traitement et de prévention. Il est nécessaire d'investir pour améliorer l'infrastructure sanitaire et la capacité des prestataires à prendre des précautions universelles contre la contamination sur les lieux de soins. De plus, il faut dispenser une formation globale et adaptée aux prestataires de soins de santé afin de renforcer leur capacité à répondre aux exigences et aux attentes de différentes sous-populations séropositives. Cela inclut non seulement les médecins, mais aussi les infirmières et les sages-femmes, qui assurent l'essentiel des soins dans beaucoup d'environnement pauvres en ressources. Des personnels bien informés et à l'écoute sont essentiels pour aider les personnes séropositives à demander et suivre le traitement, à prévenir les infections sexuellement transmissibles, les grossesses non désirées et la transmission verticale du VIH et pour soutenir une existence positive sans stigmatisation ni discrimination. Les prestataires de soins, dont certains sont séropositifs, peuvent faire la différence, particulièrement s'ils sont soutenus dans leur travail, connaissent le VIH et la santé génésique et ont les capacités requises pour assurer des soins de qualité.

Resumen

Un personal de salud capacitado es fundamental para garantizar servicios de buena calidad a las personas con VIH. Existe sólo limitada información documentada sobre los retos y las limitaciones que afrontan los prestadores de servicios de salud para cubrir las necesidades de salud sexual y reproductiva de las mujeres y los hombres VIH-positivos. En este artículo se resume la información sobre las actitudes, la motivación y el nivel de preparación de los prestadores de servicios para atender dichas necesidades, en el contexto de la crisis de recursos humanos y de las estrategias emergentes de tratamiento y prevención. Es imperativo invertir en gran medida en mejorar la infraestructura de salud y la capacidad de los prestadores de servicios para tomar precauciones universales contra la infección en los establecimientos de salud, así como capacitación integral y adecuada para que los profesionales de la salud desarrollen su capacidad para cubrir las necesidades de diferentes sectores de la población seropositiva. Entre ellos figuran no sólo médicos sino también enfermeras y parteras, quienes son las principales personas a cargo de cuidar a la mayor parte de la población en muchos lugares de bajos recursos. Los prestadores de servicios bien informados y que brindan apoyo son indispensables para ayudar a las personas VIH-positivas a buscar y seguir tratamiento, evitar las infecciones de transmisión sexual, el embarazo imprevisto y la transmisión vertical del VIH, y apoyar una vida positiva, libre de estigma y discriminación. Los profesionales de la salud, algunos de los cuales posiblemente sean VIH-positivos, pueden lograr cambios importantes, especialmente si reciben apoyo en sus condiciones de trabajo, si están bien informados respecto al VIH y la salud sexual y reproductiva, y si cuentan con las habilidades necesarias para prestar servicios de buena calidad.

Recent advances in HIV prevention and treatment modalities that offer better health and greater life expectancy to people living with HIV have influenced their sexual and reproductive expectations. Not only are the expectations of HIV positive people changing, there is also an urgency with which they expect the health system to respond to their needs. This has led to calls to expand the role of the health care system to provide sexual and reproductive health services for HIV positive people.Citation1 Yet, there are constraints within and outside the health sector that serve to undermine this expanded role for health care providers, and affect the pace and quality of services.Citation2 Health care providers are key to implementing policies and guidelines on HIV care, treatment and support. An adequately informed, skilled and motivated health workforce is critical to meeting the needs of HIV positive people, but unless they too are supported, they may become a major systems constraint in scaling-up of services.Citation3

Programmatic linkages and integration between sexual and reproductive health and HIV services are being recommended, but many missed opportunities have been documented, suggesting that providers may not be adequately addressing the sexual and reproductive health needs of HIV positive people. For example, providers at a prevention of mother-to-child transmission (PMTCT) and HIV counselling and testing site in Zambia were found to be missing many opportunities to counsel HIV positive women with family planning messages.Citation4

This paper discusses providers' practices and attitudes, motivation and level of preparedness for addressing the sexual and reproductive health needs of people living with HIV in the context of the human resources crisis and emerging treatment and prevention strategies, in both traditional health service settings and integrated reproductive health and HIV services. The paper is not intended as an exhaustive review but draws on the existing literature to call attention to pertinent issues and make recommendations for policy and programmes.

Who are the health care providers who give sexual and reproductive health services to people living with HIV

A range of health care providers – both professionally qualified and with minimal or no formal qualifications – are involved in both sexual and reproductive health care and HIV care and support. Qualified providers are chiefly physicians specialising in skin, sexually transmitted infections (STIs), obstetrics and gynaecology, general medicine and surgery; nurses and midwives; psychosocial counsellors and social workers; community outreach workers, health educators; and laboratory technicians and other paramedical staff. Others within the formal health care system include ward attendants and cleaning staff who handle hospital and human waste and disposables, including body organs, placenta and soiled linen. Chemists and pharmacists may also be involved in some countries. This paper discusses the role of providers mainly in the public sector.

It is, however, important to note that in most under-resourced countries, including some highly affected by HIV, up to 90% of HIV-related care is home-based, unpaid and mainly undertaken by women and girls,Citation5 including children, and up to 80% of AIDS-related deaths occur at home.Citation6 At the community level, care is undertaken by both formal and informal volunteers, including friends, neighbours or church members, who are mostly untrained. Formal volunteers have generally received some training and may be supervised on the job; an example are the volunteers trained at TASO in Uganda who provide a range of services such as home-based care, management of opportunistic infections, community mobilisation and antiretroviral treatment, among others. Other significant sources of community-based care come from traditional healers,Citation7 faith healers or practitioners of indigenous medicine, such as ayurveda in India.Citation8 A significant amount of care is also provided by HIV positive peer networks, particularly psychosocial services.Citation9

With new demands being placed on health care providers to deliver quality sexual and reproductive services in addition to HIV-related care and treatment, it is important to assess the suitability and capacity of the current health infrastructure and workforce for meeting these demands.

Policy frameworks and service delivery

The lack of appropriate and suitable policy frameworks to support service delivery can compromise providers' roles. In Zambia, in 1998, for example, nurses were allowed to prescribe drugs only in the absence of a doctor,Citation10 while in Kenya during the same period nurses were allowed to legally prescribe drugs to treat STIs, but information about this policy was not disseminated widely.Citation11 In many developing countries, family planning services (and more recently condoms) are not offered to unmarried adolescents and youth.Citation12 In some, certain contraceptives have not been endorsed by the government, thus constraining providers from expanding the choice of contraceptives for all women, including HIV positive women. For example, Norplant is not yet approved in India, which sex workers might find very convenient to use along with condoms. In many countries, STI medications do not yet appear on the list of essential medicines that have traditionally been given by nurses for treatment at primary level,Citation13 and rigid hierarchies within the health system may take away the authority vested in lower-level, trained cadres such as nurses and midwives from prescribing drugs in the presence of higher level medical cadres.Citation11 In countries where homosexuality is criminalised there is no

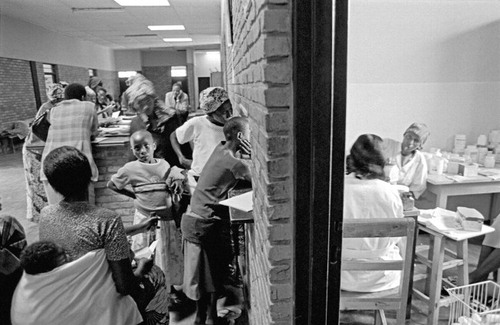

Men's HIV ward at a sanatorium near Chennai that treats the largest volume of HIV patients of any public medical facility in India, 2004

The number of nurses, midwives and other mid-level providers is much greater than physicians in most health systems, with the exception of eastern European countries and Asian countries such as Mongolia, where under the Soviet system, more physicians were trained than lower-level cadres. Hence, it might be more appropriate and cost-effective too to suggest that lower-level cadres be the ones trained for many of the tasks that an expanded programme of sexual and reproductive health care for people with HIV will need to do. These could include HIV testing, post-test and ongoing counselling and support for people with HIV and discordant couples, teaching condom use and other forms of safer sex, adherence counselling for antiretrovirals, psychosocial support, pregnancy counselling for PMTCT and delivery of PMTCT drugs antenatally and at delivery, breastfeeding and alternative feeding counselling and support – as well as the more traditional antenatal and delivery care, STI management and contraceptive provision.

Different user groups, different service orientation: providers' perceptions

Some findings suggest that providers support integration of HIV and sexual and reproductive health services, but lack the confidence and skills required to deliver services within the integrated framework. They may also have reservations about increased workload and lack of supplies, and the space and equipment needed to provide such services.Citation15Citation16 Despite the common behavioural base of both kinds of services, some providers perceive family planning to be preventive while HIV is perceived as curative; and while the former is more community-based, the latter is considered more clinic-based.Citation17

Providers trained for traditional service delivery also perceive important differences in their respective user groups. Family planning providers see their users as healthy individuals in need of contraceptives, i.e. preventive care, while STI/HIV service users are seen as symptomatic patients identified by screening or partner notification.Citation17 The sex distribution of the respective service users is also seen as problematic since the former are mainly women and the latter mostly men. In the context of Africa, it is argued that providers in the two service programmes serve two different populations and hence lack skills to provide an integrated service.Citation18 Loss of professional identity and autonomy is another concern voiced by professionals. Finally, extra demands on providers without concomitant improvements in infrastructure, working conditions and salary and career structureCitation13 have implications for overall quality of care, whether or not individual providers are supportive of an integrated programme.

Extent of providers' knowledge, clinical and counselling skills

Health care workers are sometimes found lacking in adequate knowledge about basic concepts and skills to help HIV positive people with their sexual and reproductive health needs. In a study conducted in rural Tanzania, counsellors doing breastfeeding counselling in antenatal clinics seemed to understand the importance of being sensitive and non-judgemental and perceived their role as not imposing their own values on women. But in operational terms they were lacking in clarity about the meaning of exclusive breastfeeding, the increasing risk of HIV transmission to the infant the longer a woman breastfeeds and the recommended method of weaning for infants born to HIV positive women, and they had difficulty conveying breastfeeding advice meant for HIV positive mothers. Some of the counsellors reported that they advised women to breastfeed exclusively, but also told them they could occasionally give boiled water to infants because “teaching about exclusive breastfeeding was just theory and had nothing to do with practice”. They also often did not provide non-directive counselling. They described a good counsellor as someone able to convince pregnant women to “do what the counsellor wants” and accept HIV counselling and testing, and a bad counsellor as someone who gets more refusals of testing from women.Citation19

“You give the woman a choice, but you tell her that the best she can do is to be tested. When I do pre-test counselling and she disagrees, I encourage her to be tested until she agrees.” Citation19

Understanding of dual protection and dual method use for HIV discordant couples who wish to prevent pregnancy and HIV transmission is also limited among providers. In Zambia, for example, only a few providers in the national family planning programme understood and were aware of Zambia's policy on promoting dual protection and thus only a few counselled people accordingly.Citation15

Counselling skills are critical for those serving people with HIV, but skills vary widely in depth and quality across settings. For example, the boundary between choice and coercion in provider-initiated HIV testing to women attending antenatal care may be blurred. As regards the way in which HIV testing should be offered, the proposed policy that pregnant women must routinely be offered an HIV test through either an “opt-in” or “opt-out” model is in fact still contested.Citation20–22 The opt-in model offers all women the option of choosing whether to be tested while the opt-out model informs women that they will be tested for HIV unless they specifically state that they wish to opt out. The provider's role is critical in explaining these options and in respecting people's decision, especially in the case of less educated, poor or young women and men. However, the problem of the opt-out model is that it can be used to impose testing without informing women that they have the right to refuse.Citation23Citation24 A Canadian study reported that despite policy to use the opt-out model with women in one centre, not all women seemed to know that they could opt out or even that they were being tested for HIV.Citation25

Providers of family planning services may also lack competence in practising a standardised prescriptive regimen based on risk assessment history, pelvic examination and laboratory results. This may result in the failure to counsel patients and their sex partners about transmission risk and safer sex options. At two family planning clinics in Indonesia, for example, providers failed to counsel sex partners of patients with vaginitis and cervicitis in the absence of a prescribed treatment regime and follow-up practice.Citation26

Other counselling skills that reproductive health providers need, but often lack, are in referring for HIV testing following rape, violent assault or incest. They are also often inadequately trained in teaching condom use or offering contraceptive options and sexuality education to HIV positive patients. Inadequate knowledge can frustrate both providers and service seekers, as was reported in Zambia. A study among providers and service users in family planning clinics in Zambia reported frustration among HIV positive women at the inability of providers to inform them of suitable contraceptives to avoid pregnancy.Citation15

“I feel they do not have information on safe methods of contraceptives. They know that I am HIV positive but they do not tell me the methods suitable for me.” Citation15

Information gaps also make for poor application of research findings and outdated and inadequate methods of treatment and care. Perceived lack of information, clinical and counselling skills on the part of providers are likely to confuse patients as to what practices to follow; this can discourage them from returning for care when they need it. At the same time, it can frustrate providers too, who have a perceived need for regular information updates in a field where things are changing rapidly. In Zambia, for example, providers of family planning reported feeling constrained by their own outdated knowledge and limited counselling skills in the advice they gave to HIV positive women.Citation15

“I last went for a course in family planning in 1995. A lot has changed”. (Interviewed in 2003)Citation15

Different approaches to provider training

Different training approaches have been developed to improve capacity of providers for meeting expectations of positive people. Recognising the gap in health providers' training in meeting sexual and reproductive health needs of HIV positive women and adolescent girls, EngenderHealth and the International Community of Women Living with HIV/AIDS have developed a training manual to prepare health workers to address this gap. The training curriculum is unique in two ways: in introducing the concept of integrated sexual and reproductive health counselling and in adapting counselling frameworks from sexual and reproductive health and HIV fields to assist providers in offering comprehensive services. The manual is intended for use with all staff who provide clinical care, counselling or other support services on-site or through outreach services to positive people. The manual, based on an overall philosophy of empowering women and male involvement, can be adapted for use in various cultural settings.Citation27

To address health workers' attitudes towards their work in caring for people living with HIV in India, Sharan, a leading NGO, collaborated with Horizons to draft a sensitisation manual for health care workers. This manual uses existing training modules and inputs from local AIDS service organisations and networks of people living with HIV. The training team is comprised of representatives of Sharan and representatives of HIV positive people who used interactive, participatory methods to train all levels of health workers, including doctors, nurses, cleaning and ward staff in selected hospitals. Through this training, health workers were sensitised not only to the rights of HIV positive patients but also their own right to a safe working environment and skills in providing confidential, non-discriminatory care.Citation28

Literature on the nursing experience with HIV is minimal. In the Kingston Paediatric and Perinatal HIV/AIDS Programme, selected nurses and midwives were trained in the management of PMTCT, HIV counselling and testing and the identification and nursing management of paediatric and perinatal HIV and AIDS. The programme initiated in three large maternity centres and four paediatric centres, with several feeder clinics for pregnant women. A nurse coordinator supervised the interventions at each site. A multi-disciplinary team followed protocol-driven management for the care of pregnant HIV-positive women and children. There was strong collaboration with the Jamaican government and other agencies. Among the most important aims were to “encourage other health care workers in the care of people living with HIV and AIDS; sensitise the community about HIV; improve the comfort level of positive women and families in accessing care; enable prospective data collection for programme assessment and research purposes and enhance multi-disciplinary collaboration to widen the scope of patient care and prevent duplication of health care services”.Citation29 It is evident that there are several areas in which health workers who provide sexual and reproductive health care need training. This poses specific challenges for health policymakers with regard to capacity building of the health workforce. Should everyone be trained in everything? Or does a balance need to be found between a shared foundation of basic medical skills and respect of human rights, with a certain degree of specialisation and task assignment to different cadres?

National and international guidelines and protocols for clinical practice and service delivery

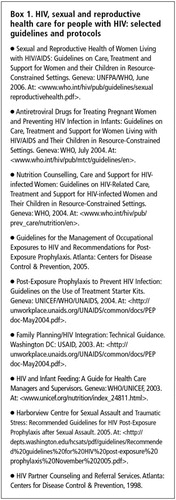

A growing number of national and international guidelines, evidence-based protocols and policies are now available to guide practice and service delivery, developed by UNAIDS, WHO and other UN agencies, the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and others (Box 1). However, providers are often unaware of theseCitation15 and quite often work out their own interpretations and practices. It is important that providers are made aware of these guidelines through both pre-service education and in-service training, and also any subsequent revisions, which can only be ensured through proper networking and dissemination systems.

A problem that providers often face is that guidelines from different sources may contain conflicting messages. With regard to partner notification for chlamydia, for example, every country in Europe has a different policy and guidelineCitation30 and this also holds true for other STIs and HIV, as well as other countries and regions. Service delivery for stigmatised conditions such as HIV also implies that guidelines must be reviewed for cultural sensitivities and norms, including gender norms. For example, studies from different countries report instances of violence, abandonment, rejection and discrimination following HIV disclosure by women.Citation31 Guidelines on partner notification for HIV, therefore, must be taken up with care. Providers must also be able to contextualise available guidelines in line with local realities and check for consonance with nationally approved policies, especially with regard to those affecting HIV positive people, including marginalised groups such as men who have sex with men. Where policies are not supportive of the right of positive people, providers need to work out ways of ensuring that services do support those rights, and it may be valuable to seek guidance from HIV positive people's advocacy and support groups to do so.

Provider attitudes, biases and discriminatory treatment

Negative attitudes and biases of providers towards people living with HIV are reported from across the world, and providers too admit that there is reluctance among some of them to provide adequate care.Citation32Citation33 A study in India reported that only 15% doctors agreed to admit HIV positive women for delivery at their clinics.Citation34 In a four-state survey in Nigeria, about 9% of the total sample of 1,103 health care professionals (doctors, nurses, midwives) working directly with HIV positive patients, reported refusing to care for positive patients and a similar proportion reported refusing them hospital admission. Nearly a third reported observing other professional colleagues refusing to care for patients with HIV and 43% observed others refusing people with HIV hospital admission.Citation35 As regards sexual and reproductive health care providers, refusal of care has been expressed through denial of assistance during labour to HIV positive pregnant women, and refusal to test the sexual partners of HIV positive people or people suspected of risky sexual behaviours. HIV positive sex workers, injection drug users and men who have sex with men in need of sexual and reproductive health care are further discriminated against and judged negatively by many health providers pushing them out of the mainstream health delivery system.Citation32

Other abuses include violations of privacy and confidentiality with regard to the sexual behaviour of people living with HIV, disclosure of HIV status and blaming for infection, pressure on HIV positive women to undergo sterilisation or abortion or not to bear (more) children, and directive counselling regarding contraceptive use and infant feeding.Citation20,21,36,37

Providers often give incomplete information due to power differentials, perceived inability of HIV patients to comprehend, negative attitudes towards the sexuality of HIV positive men and women, the judgement that HIV positive people are undeserving of services, and on the basis of their religious beliefs. Providers often encourage condom use but fail to educate people living with HIV about other safer sex methods.Citation38 In Kenya, an evaluation of counselling and testing centres found that only 58% of the counsellors informed people about the dual function of condoms and only 10% of people attending for testing were referred to family planning services.Citation39 Some providers hold strong attitudes towards unmarried youth seeking family planning services, effectively forcing them to opt for less qualified providers. In an evaluation of UN-supported pilot PMTCT projects in 11 countries, counsellors' religious background was found to be an important factor in what information was provided about family planning. In Rwanda, for instance, two of the three programmes supported by faith-based organisations offered family planning counselling involving only abstinence and delay of sexual activity, without informing people about modern contraceptive methods.Citation40

Inhibitions in dealing with sex and sexuality

Providers from both developed and developing countries, particularly those in reproductive health, admit having problems dealing with HIV positive people who report same-sex partners, doing sex work or injecting drugs. Most family planning providers in KwaZulu Natal, for example, were reported to be giving general counselling on contraceptive methods, while neglecting to talk about more “sensitive issues” related to HIV and condom use negotiation.Citation38 An assessment of health care providers' delivery of safer sex messages to HIV positive men who have sex with men showed that one in four participants was never given any safer sex counselling by their current health care provider because either the providers were unaware of or were choosing to ignore risk factors.Citation41 Other studies have shown that lack of safer sex counselling for HIV positive people is associated with limited time, insufficient reimbursement for counselling, and embarrassment and discomfort in addressing sexual issues.Citation42 Providers' difficulty accepting same-sex relationships are likely to bias service delivery or neglect certain risk patterns and related health needs, such as oral and anal STIs among men who have sex with men or male and female sex workers.Citation32

Health services infrastructure: human resources, safety measures and working conditions

Lack of sufficient supplies of basic items – e.g. needles, syringes, gloves, alcohol swabs, clinical/surgical instruments – and the fear of HIV infection forces some providers to skip procedures for people requiring sexual and reproductive health servicesCitation15 or refer patients elsewhere. Inadequacy in observing universal precautions, such as the use of gloves, makes providers reluctant to undertake procedures such as vaginal examination and IUD insertionCitation32 and undertake delivery of HIV positive pregnant women. Follow-up support to HIV positive women requiring reproductive health services can be constrained by lack of supplies such as condoms, both male and female, and their affordability and poor distribution system.Citation18 Providers' ability to reach out through home visits is usually constrained due to lack of hospital transport. Thus, visits such as post-partum visits are carried out only on a volunteer basis by committed providers outside duty hours and at their own expense.Citation19 Effectively, positive people in many health settings receive care selectively; they are accepted for procedures with perceived low risk for HIV transmission but neglected or shunted out for those perceived to be carrying a high risk of HIV transmissibility such as vaginal checks, caesarean section, sterilisation, abortion and other invasive procedures.

Other structural issues such as poor, delayed or no salaries, inadequate drug supplies, poor working environment, poor quality equipment, and no electricity or water can severely undermine providers' capacity to serve positive people and can become grounds for denial of services. Health care workers in several African countries have reported frustration due to lack of equipment and drugs and often these are a greater issue for them than poor salaries, suggesting that provider satisfaction is closely linked to the essentials required for proper service delivery.Citation43

Human resources

Many developing countries are facing a serious shortage of qualified health care workers. In Ghana, Kenya and Zambia, retaining nurses trained in STI diagnosis and management is proving difficult and there is high staff turnover.Citation11 In Mozambique, shortage of health care personnel has resulted in hiring retired personnel and lay persons as counsellors.Citation44 The exodus of trained health care workers to more developed countries and to better paying international NGOs and agencies, and luring of skilled health care workers from national health services to work in donor-controlled projectsCitation45 are contributory factors. High levels of absenteeism and staff deaths due to AIDS have compounded the problem. One assessment revealed 39% HIV prevalence among midwives and 44% among nurses in Lusaka.Citation46 In South Africa, an estimated 15.7% of health care workers were HIV positive in 2002.Citation47

Another staffing issue relates to the fact that senior physicians and specialists in many countries are mainly male, while health care staff and counsellors engaged in community work are predominantly female. There is a dearth of male workers to do community outreach for sexual and reproductive health,Citation48 which makes couple counselling more difficult. Recruitment of male counsellors would help to build a more conducive environment for partner involvement, since gender norms and values make it difficult for women to communicate with their partners about safer sex and reproductive health issues. Male counsellors could also promote gender-sensitive community education.

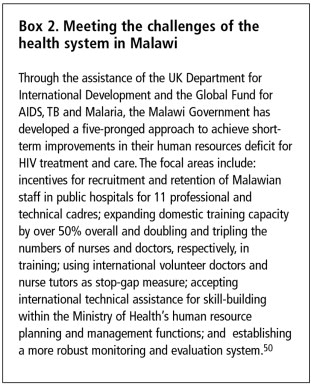

Staffing problems in HIV and reproductive care, however, need to be understood within the context of a general dearth of qualified providers worldwide. According to estimations, globally, over the next decade, an extra 334,000 professionals with midwifery skills need to be educated and 140,000 upgraded. Additionally, 27,000 doctors and technicians need to learn skills to back up maternal and newborn care. WHO estimates that US$91 billion is needed to scale up maternal and newborn services; it further estimates that a doubling or even trebling of salaries would be the minimum necessary to recruit and retain staff.Citation49 This shortfall in the health workforce is the biggest challenge to implementing national programmes that plan to add PMTCT to antenatal and delivery services. However, some governments have developed strategies to address the problems created by their dwindling health workforce and rising HIV-related health care needs (Box 2).

In this context WHO's concept of “task shifting”, to facilitate the roll-out of antiretrovirals in resource poor settings, is worth supporting. This represents a shift in global policy to allow less skilled staff or less than fully qualified staff to take on additional responsibilities.Footnote* It is a reasonable policy response in the short and medium term to the human resources crisis, but it has substantial consequences for national policy on health workers' responsibilities and training and decisions on how to strike a balance between basic, specialist and comprehensive skills.

Improving infrastructure and workplace environment

Providers need to be supported in performing their tasks well and improving their knowledge and skills. Expectations from providers as change agents must be accompanied by the acknowledgement of their own needs and rights, the need for supervision and periodic updates in training, adequate supplies and infrastructure, relevant information and guidelines, and adequate remuneration and other incentives for their work. Providers at lower cadres particularly are poorly paid and delays in payment or non-payment are quite common in many developing countries resulting in a de-motivated and demoralised staff. Equally vital is that care-giving is not treated as merely an individualised, technical job and a managerial matter, but as team work and an essential aspect of a participatory process of care and support. For example, a study in Indian hospitals demonstrated that it is important to involve providers in drawing up implementation plans for delivery of services.Citation51 When providers participate in designing care programmes, they develop a sense of ownership and commitment to deliver them well.

The exodus of trained health care providers from low-resource settings has become an important cause for concern. Decent pay structures, safe work environment, good job growth prospects and access to HIV treatment, both post-exposure prophylaxis and also antiretroviral treatment and treatment for opportunistic infections for those who are themselves HIV positive, are all essential if a qualified workforce is to be developed and retained for providing HIV and sexual and reproductive health service delivery.

Safety in the health workplace

Risk of exposure to HIV is of great concern to health care workers, especially in obstetrics, gynaecology and emergency care.Citation52 Most providers perceive invasive procedures like IUD insertion, vaginal examination, delivery, surgical procedures such as abortion, caesarean section and sterilisation, and examination of ulcerative STIs to be very risky, even with gloves on.Citation32Citation51 Fear of exposure is resulting in nurses leaving their profession, as reported from Malawi, particularly because shortages of equipment as basic as gloves are hampering adherence to universal precautions.Citation50

HIV positive people want services to be based on the human rights approach and ethical principles, and rightly so. This rights-based agenda needs to be extended to providers as well – that is, the right to a safe and non-hazardous work environment and information and the means of protection, including access to prophylaxis. Governments must invest in good quality training programmes for providers of HIV and sexual and reproductive health care, in improving working conditions in health settings and protecting health workers' rights to occupational safety. There is an urgent need to make available the means for universal precautions against infection and of post-exposure prophylaxis for occupational exposure and for all staff to be made aware of these tools and their use (Box 3).

Post-exposure prophylaxis recommendations following occupational exposure to HIV were developed by the European Occupational Post-Exposure Prophylaxis (PEP) Study Group in 2004 because prophylaxis after occupational exposure was not being used across Europe in a consistent manner. These say that if the characteristics of the exposure indicate the initiation of PEP, it should be started as soon as possible. Initiation is discouraged after 72 hours. PEP should be initiated routinely with any triple combination of antiretrovirals approved for the treatment of HIV-infected patients; a two-class regimen is preferred. The source patient's treatment history should be sought. Counselling, psychological support, HIV testing and clinical evaluation should be performed at baseline, at 6–8 weeks, and at least six months post-exposure. Additional clinical and laboratory monitoring at one and two weeks should be considered, as adherence with and tolerance of the regimen can highlight adverse reactions and potential toxicity. Routine HIV resistance tests in the source patient, and direct virus assays in the exposed health care workers are not recommended.Citation53

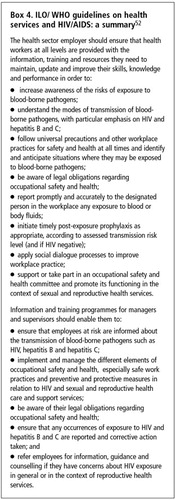

Recognising HIV transmissibility concerns among health workers and the increased load on the health system and health care providers, the International Labour Organization (ILO) and WHO have developed a set of guidelines for health services in relation to HIV and AIDS that cover legislation, policy development, occupational safety and health and other technical subjects. (Box 4).

Stress and demands of HIV care

HIV care can be extremely stressful and emotionally draining. PMTCT counsellors in rural Tanzania reported job-related stress from a heavy and demanding workload including work during off-duty hours, an unpredictable patient flow and long hours of work.Citation19 Besides work-related stress, providers are known to experience “secondary” or “courtesy” stigma, which is experienced by virtue of being associated with HIV/AIDS work.Citation29 Some providers of HIV care face disapproval from family and others over the nature of their work and loss of social status,Citation7 in addition to isolation by fellow health professionals.

Many polyclinics downright rejected and never allowed me to do HIV practice in their premises… I was not allowed inside their nursing homes even when I went with non-HIV patients. Yes, indeed they labelled me as an HIV doctor. (Physician, Mumbai, India)Citation54

Providers in resource-poor countries, particularly those highly affected by HIV, may have additional demands on their time because of high patient–provider ratio and high frustration levels due to inability to support patients' basic needs for food, shelter and clothing while counselling them on nutrition and adherence to treatment.

“The messages of TASO about living positively, eating well, looking after your health, can seem cruel when people are struggling to bring any food home.” (Ugandan provider)Citation7

The inability to practice professional detachment can be a source of high stress in high HIV prevalence settings where some providers are never able to shut the door on HIV because their own family members are HIV positive, leaving them with little respite. Over-involved providers may experience a sense of personal failure and guilt when, for example, a positive woman becomes pregnant despite coming for counselling for family planning.Citation7 In high HIV prevalence settings, where achieving targets and measuring programme success often take priority over arranging retreats and rest for providers, burnout is a major issue.

“It's a fact that outside donors are not really concerned with staff welfare matters – they are more interested in how many clients can be reached for the amount of money they give.” (Health care provider, member of TASO, Uganda)Citation7

Caring for the carers

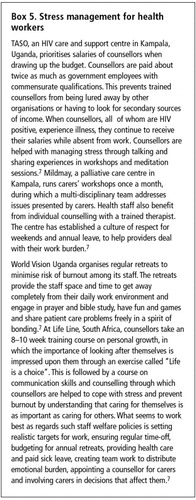

Stress management must also be recognised as essential to improving provider productivity and sensitive response to people living with HIV, as with all patients. A few NGOs in Uganda, South Africa and other parts of Africa have services that address providers' needs which may be used and adapted as models elsewhere (Box 5).

Improving the knowledge base and training in counselling, clinical and rights-based skills

In order to meet the sexual and reproductive health needs of HIV positive people, providers must not only have clinical skills, knowledge of bio-medical aspects and skills for care and counselling, but also a good level of knowledge of national programmes and programmatic linkages and an understanding of, and sensitivity to, rights and gender issues in the context of HIV/AIDS.

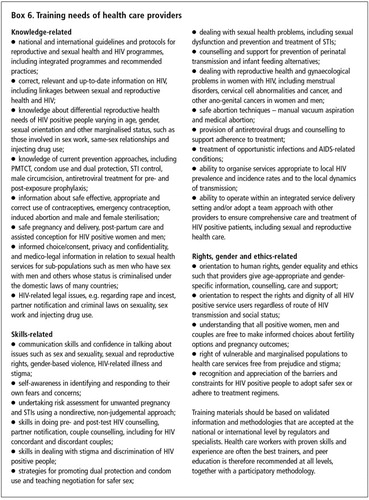

Training programmes must be designed to promote self-reflection among providers on their attitudes, values, biases, knowledge levels and practice in HIV care and to develop sensitivity to people's right to care and treatment regardless of their HIV status or mode of HIV acquisition. A proper orientation must be done to acquaint providers with situations and contexts of vulnerability to HIV with specific reference to HIV positive people who are marginalised due to the nature of their work, sex, age, sexual practices and sexual identity. There is an urgent need to build capacity to care for the sexual and reproductive health needs of different sub-populations of HIV positive people, which may differ widely (Box 6). Thus, training programmes designed for providers of HIV care to heterosexual couples may have different components from those for providers who serve migrant workers, prisoners, street children, injecting drug users, men who have sex with men and male and female sex workers.

Providers in HIV care must be trained to anticipate additional counselling and support needs for positive women and men to help them make choices regarding sexuality, pregnancy, and childbearing. For example, women accessing services from the PMTCT programme in Thailand spoke positively about the health care provider who informed them about the reduced risk of transmitting HIV to their unborn child if they enrolled in the PMTCT programme. Based on this advice, some of the women who were uncertain decided to continue with their pregnancies.Citation55

Equally important is the need to train family planning providers in assessing risk for STIs. At a family planning centre in Mexico when women were informed of risk factors for and prevention of STIs, they were able to ask questions during contraceptive counselling, and consequently fewer inappropriately chose an IUD for contraception. However, providers not trained to assess STI-related risks more often recommended an IUD inappropriately.Citation56

Providers must also be oriented to the socio-economic barriers to health care, namely access to transport, job loss and competing health care and other needs of patients such as childcare arrangements so that they do not blame them for delayed treatment-seeking or poor treatment adherence.

Most HIV-related in-service training for health care providers in developing countries currently is a one-time, short-term programme – from eight hours to one full week for physicians and nurses. There are hardly any programmes designed for other support staff, e.g. ward attendants and waste cleaners. Even where national policies on HIV are in place, adequate staff training on HIV is not provided. Yet, various studies in India, Latin America and parts of Africa (Zambia, Senegal, Uganda) suggest that participatory, rights-based training programmes help in increasing provider knowledge, sensitising them to gender and rights-based approaches to health care, reducing AIDS-related stigma and discrimination, and improving their skills in assessing risks and vulnerabilities of those seeking health care.Citation51,57,58

Training health care workers in remote and difficult-to-reach locations with poor road/rail connectivity is another critical issue. They are hard to reach for trainers and likely to experience language barriers and other issues of supervision and information flow.

Expanding the provider base: traditional and HIV positive peer support and informal systems

Given the weaknesses in the health systems of many developing countries, broadening the range of health care providers to include informal and less trained providers is being seen as a way to tackle problems.Citation59 In many developing countries a significant proportion of patients with STIs and those needing services for abortion and other stigmatising conditions often seek services outside the structured and formal health system. It is therefore important that these providers be trained in at least some aspects of sexual and reproductive health care for people living with HIV.

Worldwide more than one million women living with HIV are estimated to deliver their babies without the help of skilled attendants.Citation60 The role of traditional birth attendants (TBAs) becomes critical in such contexts. In Kenya, for example, TBAs are being trained to promote PMTCT and recognise high-risk complications in HIV positive women. They are also being paid for record-keeping and for accompanying women with complications to clinics for treatment.Citation61 However, caution has been expressedCitation62Citation63 about the limits of depending on TBAs for giving services to positive women instead of training skilled midwives for these tasks. However, in some resource-poor countries, resources are not being directed towards making this change.

In many parts of Africa, traditional healers (herbalists, spiritualists or those practising both) play an important role in people's health including in the lives of those affected by HIV and AIDS. In 1994, WHO recommended upgrading their skills and collaborating with them at a formal level. Accordingly, a few collaborative initiatives were attempted between traditional and biomedical practitioners for HIV prevention, education and counselling, and were evaluated for effectiveness, efficiency, sustainability, relevance and ethical soundness. One such attempt was made with the Inanda healers from the Valley of a Thousand Hills, KwaZulu Natal, South Africa, in 2000. A group of 16–20 healers attended one-day, monthly workshops to learn about HIV transmission, prevention, treatment and care. Participants also discussed traditional and cultural sexual practices and safer sex beyond condoms to prevent HIV transmission. The workshop resulted in the establishment of a referral network between the traditional healers and the formal health sector. The region has seen an increase in requests for HIV testing, counselling and support through the healers. Traditional healers' involvement in meeting sexual and reproductive health needs of positive people is a viable option especially in high HIV prevalence settings. The UNAIDS guidelines are available for empowering governmental and non-governmental agencies in fostering productive collaborations between the traditional and modern health systems.Citation59

Involving HIV positive people as peer support and care providers is a widely supported strategy.Citation21 However, HIV positive people are still greatly under-utilised in care and support services, where they could more often be effective counsellors for recently diagnosed individuals in exemplifying living positively after an HIV diagnosis, in confronting sexual health issues and in reducing AIDS-related shame and stigma from counselling. HIV positive people are more likely to be perceived by newly diagnosed men and women as sympathetic towards those testing positive and more trustworthy and empathetic because of their own lived experience.Citation64 Their understanding of the realities of those affected with HIV could generate a greater demand for testing, treatment and care, provide the emotional base for support many people need and help to prevent the further transmission of HIV.

Involvement of private health care providers

Stigma and discrimination and lack of services and quality of care in the public sector have forced many HIV positive people to seek care from private practitioners, including qualified, trained allopathic providers. There are, however, some concerns about the role of the private sector in HIV care because of the lack of sexual and reproductive health-specific and HIV-linked training, and their sometimes poor uptake of evidence-based practice following national and international guidelines on HIV-related issues. In India, 66% of trained private providers, mainly physicians, admitted testing and diagnosing HIV infection and 14% prescribed antiretroviral drugs but were found not to have adequate knowledge of the national guidelines for antiretroviral use.Citation65 An added concern in many countries is that the private sector is largely unregulated and widely dispersed. Private providers may also lack links with NGOs and the public sector, which may result in gaps in continuity of care of HIV patients. However, there is no denying that this professionally trained workforce can be and sometimes is a vital human resource for providing health services to positive people. Strategies are urgently needed for their training in HIV-related sexual and reproductive health care similar to that for public sector providers, and for linking these two sets of services through national reporting requirements and adherence to accepted standards and national guidelines. One such successful attempt was made in New Delhi, India, where a large private sector hospital willingly engaged with NGOs and public sector hospitals in designing and implementing an AIDS-stigma reduction intervention endorsed by the National AIDS Programme.Citation51

Health service policy and programmatic issues for governments

Governments need to draw up a workplace policy for the health sector, promoting and protecting the rights of both health care providers to safer work conditions, and of HIV positive service users and patients to non-discriminatory health services. But framing policies is not sufficient unless they are implemented and enforced. In many countries workplace policies have had little impact as they remain un-resourced, un-enforced and un-regulated.

Governments need to invest more in medical education and in-service training programmes to improve and strengthen informed and up-to-date sexual and reproductive health care for HIV positive people. Nurses and midwives are the primary health care providers for most of the population in sub-Saharan Africa and other resource-poor health systems, and the backbone of the new PMTCT programmes. They will also be the most likely primary level providers available to diagnose and treat opportunistic infections and dispense antiretroviral therapy.Citation66 Medical, nursing and midwifery curricula must be revised to respond to emerging prevention and treatment modalities and scientific advances in HIV prevention, treatment and care. Capacity building must be participatory and inclusive of all levels of health cadres. The approach of training programmes should be towards transforming provider–patient relationships from service delivery only of a clinical nature to one that is mutually respectful and patient-centred. Quality assurance and follow-up of capacity building initiatives must be built in along with mechanisms for monitoring and evaluation of training, with periodic reinforcement of newly acquired skills. Staff replacement is costly, and human resource planning is required to build a sufficient pool of trained health care professionals. At the same time, ethical recruitment policies must be in place which are sensitive to the rights of health care providers to professional mobility, the needs of the country of origin to retain experienced staff and the needs of host countries to recruit more staff.

Policy changes are also required for expanding the list of who can do HIV testing and provide counselling, and who can diagnose certain conditions, prescribe and hand out medication and perform procedures, to increase availability of treatment and care for HIV positive as well as other service users and patients. Advocacy is also needed to support legislative changes in providing HIV positive adolescents with appropriate HIV and sexual and reproductive health services. Where qualified providers are few and HIV prevalence levels are high, consideration should be given to creating new cadres of mid-level providers, including HIV positive people, who receive basic training for home-based care and support, support for antiretroviral and other drug adherence and many other straightforward procedures.

Conclusion

Health care providers are crucial for helping HIV positive people prevent sexually transmitted infections, unintended pregnancy and vertical transmission of HIV, and also to support positive living, including the enjoyment of a healthy sex life and relationships free from stigma and discrimination. Providers, some of whom are also HIV positive, can make an important difference, especially if they are supported in their working conditions, are knowledgeable about HIV and sexual and reproductive health and rights and have the skills to provide good quality care.

Notes

* The World Health Report 2006 is a comprehensive account of human resources for health. At: <www.who.int/whr/2006/en/>.

References

- M Stratchan, A Kwateng-Addo, K Hardee An analysis of family planning content in HIV/AIDS, VCT, and PMTCT policies in 16 countries. POLICY Working Paper Series, No. 9. 2004, Policy Project. Washington DC.

- World Health Organization, Scaling up HIV/AIDS care: service delivery and human resources perspectives. 2004, WHO. Geneva. At: <www.who.int/entity/hrh/documents/HRH_ART_paper.pdf>.

- K Kober, W van Damme. Scaling up access to antiretroviral treatment in southern Africa: who will do the job?. Lancet; 364(9428), 2004:103-107.

- N Rutenberg Family planning and PMTCT services: examining interrelationships, strengthening linkages. Horizons Research Summary. 2003, Population Council. Washington DC.

- J Ogden, S Esim, C Grown Expanding the care continuum for HIV/AIDS: bringing carers into focus. 2004, International Center for Research on Women. Washington DC.

- L Uys. Longer-term aid to combat AIDS [Guest Editorial]. Journal of Advance Nursing; 44(1), 2000:1-2.

- UNAIDS, Caring for Carers: Managing Stress in Those Who Care for People with HIV and AIDS. 2000, UNAIDS. Geneva.

- S Bharat Facing the challenge: household and community responses to HIV/AIDS in Mumbai, India. 1996, WHO, UNAIDS. Geneva.

- Horizons, International HIV/AIDS Alliance, Greater involvement of PLHA in NGO service delivery: findings from a four-country study. 2002, Population Council. Washington DC.

- CF Mutungwa, KC Nkwemu Barriers and opportunities for integration of STD/HIV and MCH/FP service in Zambia. 1998, Planned Parenthood Association of Zambia. Lusaka.

- E Njeru, J Njoka Barriers and opportunities for integration of STD/HIV and MCH/FP service in Kenya. 1998, Sociology Department, University of Nairobi. Nairobi.

- K Wood, P Aggleton Promoting young people's sexual and reproductive health: stigma, discrimination and human rights. Safe Passages to Adulthood. 2004, Thomas Coram Research Unit, Institute of Education, University of London. London.

- L Lush. Service integration: an overview of policy developments. International Family Planning Perspectives; 28(2), 2002:71-76.

- S Khan, A Bandhyopadhyay, P Causey Risks and responsibilities: male sexual health and HIV in Asia and the Pacific. 2006, International consultation. India.

- HN Banda, S Bradley, K Hardee Provision and use of family planning in the context of HIV/AIDS in Zambia: perspectives of providers, family planning and antenatal care clients, and HIV-positive women. 2004, Policy Project. Washington DC. At: <www.policyproject.com/pubs/countryreports/Zam_FGD.pdf>.

- P Maharaj. Integrated reproductive health services: the perspectives of providers. Curationis; 27(1), 2004:23-30.

- R Kane, K Wellings. Integrated sexual health services: the views of medical professionals. Culture, Health and Sexuality; 1(2), 1999:131-146.

- JE Mantell, S Hoffman, TM Exner. Family planning providers' perspectives on dual protection. Perspectives in Sexual and Reproductive Health; 35(2), 2003:71-78.

- MM de Paoli, R Manongi, KI Klepp. Counsellors' perspectives on antenatal HIV testing and infant feeding dilemmas facing women with HIV in Northern Tanzania. Reproductive Health Matters; 10(20), 2002:144-156.

- Asia-Pacific Network of People Living with HIV/AIDS. AIDS Discrimination in Asia, 2004. At: <www/gnpplus.net/regions/human_rights_initiative.doc. >.

- International Community of Women Living with HIV/AIDS, HIV positive women and human rights. ICW Vision Paper 4. 2004, ICW. London.

- Medrek M, Eckman AK, Yaremenko O, et al. Problems HIV-positive women face accessing reproductive health care in Ukraine. Abstract TuPeE5404, Bangkok: XV International Conference on AIDS, 2004..

- E Lindsey HIV-infected women and their families: psychosocial support and related issues. A literature review. 2003, WHO. Geneva.

- Health and Development Network. Why we should oppose a return by stealth to the days of mandatory HIV testing. Newsletter. Bangkok: XV International Conference on AIDS, 2004..

- Margolese SL. HIV testing and pregnancy: protecting access to informed consent through community action in Canada. Poster abstract ThPeE7981. Bangkok: XV International Conference on AIDS, 2004..

- MP Budiharsana. Integrating reproductive tract infections services into family planning settings in Indonesia. International Family Planning Perspectives; 28(2), 2001:111-112.

- EngenderHealth, International Community of Women Living with HIV/AIDS, Sexual and Reproductive Health for HIV-positive Women and Adolescent Girls: Manual for Trainers and Program Managers. 2006, EngenderHealth, ICW. New York.

- Sharan, Horizons, Sensitization Training for Health Care Workers Providing HIV Care: Facilitator's Manual (Working draft). 2004, Sharan. New Delhi.

- PM Palmer, MM Anderson-Allen, CC Billings. Nursing interventions in the Kingston Paediatric and Perinatal HIV/AIDS Programme in Jamaica. West Indian Medical Journal; 53(5), 2004:327-331.

- N Low, A McCarthy, TE Roberts. Partner notification of chlamydia infection in primary care: randomised controlled trial and analysis of resource use. BMJ; 3322006:14-18.

- S Maman, A Medley Gender dimensions of HIV status disclosure to sexual partners: rates, barriers and outcomes. A review paper. 2004, WHO. Geneva. At: <www.who.int/gender/documents/en/genderdimensions.pdf>.

- S Bharat, P Aggleton India: HIV and AIDS related discrimination, stigmatisation and denial. UNAIDS Best Practice Collection, Key Material. 2001, UNAIDS. Geneva.

- KT Hong, NT Van Anh Understanding HIV and AIDS-related stigma and discrimination in Vietnam. 2004, International Council for Research on Women. Washington DC.

- VT Mhase, PSN Reddy. Risk perception and reaction to HIV/AIDS as an occupational health hazard among medical practitioners in a suburb of Mumbai. Indian Journal of Occupational Health; April–June2000:81-84.

- G Letamo. The discriminatory attitudes of health workers against people living with HIV. PLoS Medicine; 2(8), 2001:e261.

- V Paiva, FE Ventura, N Santos. The right to love: the desire for parenthood among men living with HIV. Reproductive Health Matters; 11(22), 2003:91-100.

- Mahendra V, Sarna A, Rutenberg N, et al. Does the PMTCT program facilitate access to HIV care and SRH services for HIV-positive women? Experiences from India. XVI International AIDS Conference, Toronto, Canada 13–17 August 2006..

- L Ndhlovu, C Searle, R Miller Reproductive health services in KwaZulu Natal, South Africa: a situation analysis study focusing on HIV/AIDS services. 2003, Population Council. Washington DC.

- HW Reynolds, J Liku, MB Ndugga Assessment of voluntary counselling and testing centers in Kenya. Potential demand, acceptability, readiness, and feasibility of integrating family planning services into VCT. 2003, Family Health International. Arlington VA.

- N Rutenberg, C Baek, S Kalibala Evaluation of United Nations-supported pilot projects for the prevention of mother-to-child transmission of HIV. 2003, UNICEF. New York.

- AD Margolis, RJ Wolitski, JT Parsons. Are healthcare providers talking to HIV-sero-positive patients about safer sex?. AIDS; 15(17), 2001:2335-2337.

- J Bluespruce, WT Dodge, L Grothaus. HIV prevention in primary care: impact of a clinical intervention. AIDS Patient Care and STDs; 152001:1-11.

- S Fonn, AS Mtonga, HC Nkoloma. Health providers' opinions on provider–client relations: results of a multi-country study to test health workers for change. Health Policy and Planning; 16(Suppl. 1), 2001:19-23.

- H Van Rooyen, V Solomon South African Development Community VCT final workshop report. 2002, SADC.

- M Berer. Health sector reforms: implications for sexual and reproductive health services. Reproductive Health Matters; 10(20), 2002:6-15.

- HIV positive women have different needs Network; 20(4), 2001.

- O Shisana, EJ Hall, R Maluleke. HIV/AIDS prevalence among South African health workers. South African Medical Journal; 94(10), 2004:846-850.

- S Bharat Social assessment of the reproductive and child health programme – the Mumbai experience. 2003, Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, Department for International Development. New Delhi.

- N Gerein, A Green, S Pearson. The implications of shortage of health professionals for maternal health in sub-Saharan Africa. Reproductive Health Matters; 14(27), 2006:40-50.

- D Palmer. Tackling Malawi's human resource crisis. Reproductive Health Matters; 14(27), 2006:27-39.

- VS Mahendra, L Gilborn, B George Reducing AIDS-related stigma and discrimination in Indian hospitals. 2006, Population Council. New Delhi.

- International Labour Organization World Health Organization, Draft joint ILO/WHO Guidelines on health services and HIV/AIDS. 2005, ILO/WHO. Geneva. (European Surveillance [abstract] 2004;9(6);40–43).

- V Puro, S Sicalini, G De Carli. Towards a standard HIV post exposure prophylaxis for healthcare workers in Europe. [Abstract]European Surveillance; 9(6), 2004:40-43.

- S Bharat Challenging AIDS stigma and discrimination in south Asia. Report of an Electronic Discussion Forum. 2004, UNAIDS, Tata Institute of Social Sciences. Mumbai.

- International Community of Women Living with HIV/AIDS, HIV Positive Women in Thailand – Their Voices and Choices. 2001, ICW. London.

- EC Lazcano Ponce, NL Sloan, B Winikoff. The power of information and contraceptive choice in a family planning setting in Mexico. Sexually Transmitted Infections; 76(4), 2000:277-281.

- JF Helzner. Transforming family planning services in the Latin American and Caribbean region. Studies in Family Planning; 33(1), 2002:49-60.

- S Fonn, M Xaba. Health workers for change: developing the initiative. Health Policy and Planning; 16(Suppl. 1), 2001:13-18.

- UNAIDS, Collaboration with traditional healers in HIV/AIDS prevention and care in sub-Saharan Africa: a literature review. 2000, UNAIDS. Geneva.

- M Bulterys, MG Fowler, N Shaffer. Role of traditional birth attendants in preventing perinatal transmission of HIV. BMJ; 3242002:222-224.

- Kaai S, Baek C, Geibel S, et al. Experiences of postpartum women with PMTCT: the need for community-based approaches. 11th Reproductive Health Research Priorities Conference, Sun City, South Africa, 2004..

- G Walraven. Commentary: involving traditional birth attendants in prevention of HIV transmission needs careful consideration. BMJ; 3242002:224-225.

- M Berer. Traditional birth attendants in developing countries cannot be expected to carry out HIV/AIDS prevention and treatment activities. Reproductive Health Matters; 11(22), 2004:36-39.

- M de Bruyn, S Paxton. HIV testing of pregnant women: what is needed to protect positive women's needs and rights?. Sexual Health; 2(3), 2005:143-151.

- K Sheikh, S Rangan, D Deshmukh. Urban private practitioners: potential partners in the care of patients with HIV/AIDS. National Medical Journal of India; 18(1), 2005:32-36.

- J Raisler, J Cohn. Mothers, midwives, and HIV/AIDS in Sub-Saharan Africa. Journal of Midwifery and Women's Health; 50(4), 2005:275-282.