Abstract

In many areas of the globe most HIV infection is transmitted sexually or in association with pregnancy, childbirth and breastfeeding, raising the need for sexual and reproductive health and HIV/AIDS initiatives to be mutually reinforcing. Many people with HIV, who are in good health, will want to have children, and highly active antiretroviral therapy provides women and men living with AIDS the possibility of envisaging new life projects such as parenthood, because of a return to health. However, there are still difficult choices to face concerning sexuality, parenthood desires and family life. Structural, social and cultural issues, as well as the lack of programmatic support, hinder the fulfilment of the right to quality sexual and reproductive health care and support for having a family. This paper addresses the continuum of care involved in parenthood for people living with HIV, from pregnancy to infant and child care, and provides evidence-based examples of policies and programmes that integrate sexual and reproductive health interventions with HIV/AIDS care in order to support parenthood. Focusing on parenthood for people living with and affected by HIV, that is, focusing on the couple rather than the woman as the unit of care, the individual or the set of adults who are responsible for raising children, would be an innovative programmatic advance. Going beyond maternal and child health care to providing care and support for parents and others who are responsible for raising children is especially relevant for those living with HIV infection.

Résumé

Dans de nombreuses régions du monde, l'infection à VIH est transmise par voie sexuelle ou en association avec la grossesse, l'accouchement et l'allaitement maternel, ce qui exige des initiatives de santé génésique et de lutte contre le VIH/SIDA se renforçant mutuellement. Bien de personnes en bonne santé vivant avec VIH voudront avoir des enfants. Ayant recouvré la santé grâce à l'efficacité du traitement antirétroviral, les femmes et les hommes avec SIDA envisagent de nouveaux projets, par exemple avoir des enfants. Néanmoins, ils doivent encore faire des choix difficiles concernant la sexualité, le désir d'enfant et la vie familiale. Des questions structurelles, sociales et culturelles, ainsi que le manque de soutien des programmes, entravent la réalisation du droit à des soins de santé génésique de qualité et un soutien pour fonder une famille. L'article décrit l'assistance nécessaire pour les parents vivant avec le VIH, de la grossesse aux soins à donner aux nourrissons et aux enfants, et donne des exemples de politiques et de programmes qui intègrent des interventions de santé génésique avec les soins en matière de VIH/SIDA afin de soutenir la paternité. Se centrer sur la fonction parentale pour les personnes vivant avec le VIH ou touchées par le virus, c'est-à-dire sur le couple plutôt que sur la femme comme unité de soins, l'individu ou l'ensemble d'adultes qui élèvent des enfants, serait une bonne innovation pour les programmes. Pour les personnes séropositives, il est particulièrement important de dépasser les soins de santé maternelle et infantile pour soutenir les parents et d'autres responsables de l'éducation des enfants.

Resumen

En muchas regiones del mundo, la mayoría de las infecciones por VIH son transmitidas sexualmente o en asociación con el embarazo, el parto o la lactancia, por lo cual es esencial que las iniciativas de salud sexual y reproductiva y VIH/SIDA se refuercen mutuamente. Muchas personas que viven con VIH y que gozan de buena salud van a querer hijos. Una terapia antirretroviral muy activa les brinda a las personas que viven con SIDA la posibilidad de concebir nuevos proyectos de vida, como la paternidad, una vez recobran su salud. Sin embargo, aún deben tomar decisiones difíciles respecto a la sexualidad, los deseos de paternidad y la vida en familia. Los aspectos estructurales, sociales y culturales, así como la falta de apoyo programático, obstruyen el goce del derecho a servicios de salud sexual y reproductiva de calidad y el apoyo para tener una familia. Este artículo trata sobre el continuo de atención implicada en la paternidad de las personas seropositivas, desde el embarazo hasta los cuidados de bebés y niños, y expone ejemplos basados en evidencia de políticas y programas que integran las intervenciones de salud sexual y reproductiva a la atención del VIH/SIDA a fin de apoyar la paternidad. El centrarse en la paternidad de las personas que viven con VIH y son afectadas por éste, es decir, centrarse en la pareja y no en la mujer como la unidad de cuidados, la persona o la pareja de adultos responsables de criar a los hijos, sería un avance programático innovador. El trascender la atención a la salud materno-infantil para proporcionar cuidados y apoyo a los padres y otros responsables de criar a los niños es especialmente pertinente para las personas que viven con infección por VIH.

In many areas of the globe most HIV infection is transmitted sexually or in association with pregnancy, childbirth and breastfeeding, raising the need for sexual and reproductive health and HIV/AIDS initiatives to be mutually reinforcing. Most women and men living with HIV are of childbearing age and face difficult choices concerning their sexuality, parenthood desires and family life.

HIV infection affects the way women and men experience parenthood. It has a negative impact on their ability to have children, related not only to psychosocial aspects such as stigma and discrimination and decreased sexual activity, but also to the clinical impact of HIV infection and sexually transmitted infections (STIs) on fertility.Citation1Citation2 Recently, the availability of highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART) and of interventions for prevention of mother-to-child transmission (PMTCT) in more countries has markedly changed the life prospects of people living with HIV, creating the possibility of new life projects, including parenthood.Citation3–6

Structural, social and cultural conditions, as well as the existence or absence of policies and programmatic support, may affect access to health care and family formation. Such barriers are not restricted to resource-constrained settings. In countries where antiretrovirals are available, women and men experience similar challenges, including lack of information regarding safe pregnancy and PMTCT, negative attitudes towards HIV positive people having children and problems accessing safe, legal abortions.Citation7Citation8 Worldwide, differences in provision of skilled care, service infrastructure and human resources, availability of voluntary counselling and testing (VCT), access to condoms and contraceptives, medication and HAART, sum up the issues affecting reproductive choices for women and men living with HIV.

HIV infection has been associated with sexual promiscuity, family disorganisation and drug use, dimensions of life seen as “incurable deviancy”.Citation7 Moreover, historical and cultural definitions of parenthood and reproduction as women's issues may also influence the organisation of prevention and care services. Men often prefer larger families than women in many parts of the developing world.Citation9 Consistent with demographic studies, the desire to have children among Brazilian people living with HIV is more frequent among men than among women, and has been quite prevalent as well in developed countries, whether the men are bisexual or heterosexual.Citation3,5,7 In addition, men have their own unmet reproductive and sexual health needs;Citation10Citation11 men's access to and involvement in provision of these services thus needs to be addressed and may help to decrease gender inequality and facilitate HIV prevention.Citation12Citation13 Improvements in understanding of pregnancy and lower perinatal mortality have been documented in India among women whose husbands received antenatal educationCitation14Citation15 while in Jamaica, Zimbabwe and Vietnam, long-lasting effects have been found among fathers as a result of involvement in the lives of their children, including higher self-esteem and higher educational achievement in their children.Citation16

It is thus important to analyse how far the reproductive needs of women and men living with HIV are currently being met by health services and what challenges and obstacles at the programmatic and service delivery levels might impair the fulfilment of their reproductive rights. This paper addresses the continuum of care involved for those who wish to be parents, from the point of starting a pregnancy through delivery and infant and child care. It provides evidence-based examples of policies and programmes that integrate sexual and reproductive health interventions with HIV/AIDS care. Stigma and discrimination, male involvement and provision of care by trained health care workers are dealt with as cross-cutting issues throughout.

Pregnancy care

The links between antenatal care and HIV prevention and care should start from women's own perspectives and the local context. Most pregnant women who seek antenatal care worldwide are not aware of their HIV serostatus. In addition, pregnant women from different socio-cultural contexts experience intense inequalities in access to health care services and to information regarding the benefit of antenatal care for themselves and their babies. Illiteracy or little schooling, young age, position in the family and economic dependence upon others, limited mobility due to poverty, religious or cultural restrictions or being a member of a marginalised population group represent major barriers to accessing antenatal care.Citation17Citation18

Antenatal care is the port of entry to the health care system for the majority of women of reproductive age. Antenatal care may be available variously through community and home-based care, primary care units, NGO services, faith-based facilities, private clinics, public maternity clinics or hospitals. Depending on the particular features of each service, as well as on health care professionals' attitudes towards HIV and AIDS, HIV prevention and treatment and care for HIV positive women may not be provided, and counselling and management opportunities, including the window of opportunity for involving male partners during pregnancy, may be missed.

Antenatal care providers should encourage and support pregnant women to access HIV testing and counselling in a caring atmosphere.Footnote* Pregnant women must be seen as women in their own right, not only as mothers-to-be, and HIV testing should not only be a means to accomplish prevention of mother-to-child transmission. Testing is an opportunity for early diagnosis of HIV infection that enables access to HIV management, including antiretroviral treatment and prevention of opportunistic infections, to ensure better long-term prognosis and quality of life for women, their children and families. Antenatal care providers should inform women about the benefits of HIV testing and encourage them, ensuring support against stigma and discrimination throughout the diagnostic process.

Women will most likely accept testing if it is offered,Citation19 especially if HIV treatment is available. For example, acceptance of HIV testing in antenatal care has been shown to be associated with knowledge about availability of antiretroviral drugs for PMTCT in the USA.Citation20 Expanding antiretroviral treatment for pregnant women worldwide may thus contribute to higher acceptance of testing. Many women believe having an HIV test is unnecessary because they assume they have faithful spouses or do not belong to “risk groups”.Citation21 The universal offer of testing increases the likelihood that a pregnant woman will be screened. Different strategies have been used to scale-up the offer of HIV testing during pregnancy. In the “opt-in” approach, traditional voluntary counselling and testing strategies are employed, women receive pre-test counselling and informed consent is obtained before blood is drawn.Citation22 This approach assumes testing is an intrinsic part of antenatal care, and women are given the opportunity to refuse. However, it is important to point out that with the “opt-in” approach many women might not find out their HIV serostatus before delivery, resulting in missed opportunities for access to care for the whole family. Alternatively, the “opt-out” approach treats HIV screening as routine, along with screening for syphilis and hepatitis B. The woman is informed that testing will be performed, but consent is implied unless she specifically refuses. Though this approach is usually associated with wider coverage,Citation23 there is still concern that it may turn into imposition of HIV tests, since many patients are reluctant to challenge health care procedures.Citation21

It is also crucial to consider the psychosocial implications of testing during pregnancy. Disclosure of HIV diagnosis during pregnancy, in the absence of treatment and support, may bring about devastating psychosocial consequences of stigma and discrimination that in some countries exist even within the health care sector. Examples are remarkably similar across regions of denial of treatment, humiliating and stigmatising attitudes and breaches of confidentiality have been experienced, especially in non-specialist health care and obstetric and gynaecology clinics. These include refusal to bring women food or clean their rooms, or not letting them deliver at the hospital because the hospital was “not ready for such complicated cases”.Citation21

Antenatal care providers should be trained to provide counselling about HIV and other STIs. Although the presentation of and treatment response to some STIs may be altered in women with HIV, standard treatment protocols are usually effective unless there is severe immune suppression.Citation24Citation25 Training of providers should also address multiple deprivation and vulnerability. A community-based nursing organisation in Detroit, USA, for example, initiated a successful service delivery model based on getting highly vulnerable HIV positive women with a history of substance abuse and mental illness who had had little or no health care access into specialist clinics.Citation26

Additionally, fostering male involvement and focusing care approaches on the couple rather than exclusively on women may enhance the experience of pregnancy. Involving men in the reproductive health care of their partners was shown to be acceptable and feasible in KwaZulu–Natal. Women reported that their partners were more helpful and interested, and learned what to do and not do; men reported more trust and being together and having learned useful things; health care providers thought that involving men could bring families closer together, help fathers to become closer to their children and reduce gender-based violence. However, several challenges were recognised at the health service delivery level that would need to be addressed before maternity services become more male-friendly. These included traditional beliefs, obstacles for working fathers to attend, a significant number of couples who were not cohabiting and men with multiple partners who did not want to be seen.Citation27

Nor are partners always supportive. Some women worry that their partner will find out they are HIV positive and fear being abandoned or of experiencing violence.Citation19Citation28 Couple counselling if women wish to include their partner is an alternative approach and testing after obtaining joint consent has been implemented in some settings in an attempt to reduce women's vulnerability. This approach may also enhance male involvement.Citation29

Nevertheless, couple counselling might not be enough to guarantee success in avoiding violence. A recent Zambian study showed that even though women in antenatal care who were counselled with their partners were more likely to accept HIV testing compared to women counselled alone, there were no significant differences between the two groups in reported adverse social events, including physical violence, verbal abuse, divorce or separation after disclosure of serostatus.Citation30

Many women experience violence during pregnancy, with harmful consequences both for themselves and their babies, such as spontaneous abortion, pre-term labour and low birthweight. Health care workers must be aware of this and seek to ensure that women receive the counselling, care and referrals they may require to mitigate the risk of intimate partner violence.Citation31Citation32 Among HIV positive women in the USA, the overall prevalence of domestic or sexual violence may be as high as 68%, with increased risk after disclosure of HIV serostatus.Citation33–35

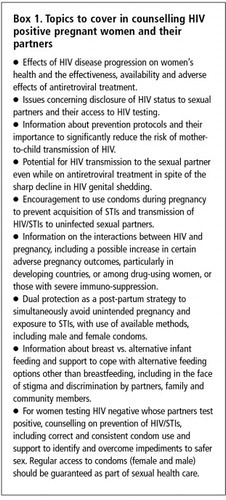

Integrating women's perspectives on when and how to learn their HIV status is thus crucial for antenatal HIV screening. Box 1 outlines a comprehensive approach for counselling pregnant women and their partners. Evidence from qualitative research has highlighted the importance of a woman's awareness of her HIV status, as well as the need to maintain the voluntary nature of testing.Citation36 Women's HIV status must be kept confidential and their medical records available only to health care workers with a direct role in their own or their infants' care.

Impact of pregnancy on HIV

Though pregnancy is believed to constitute an immensely complex physiological and immunological state, it does not appear to accelerate HIV disease progression. There is evidence that pregnancy is associated with a decline in mean CD4+ cell counts and altered CD8+ cell counts in HIV positive women, but the clinical implications of these changes are unclear. Nor does there appear to be an association between pregnancy and HIV plasma viral load.Citation22

Impact of maternal HIV infection on pregnancy and perinatal outcome

Even though most pregnancies in HIV positive women, especially if asymptomatic, are free of complications, a meta-analysis of cohort studies comparing seropositive pregnant women with their seronegative counterparts showed that maternal infection was associated with various adverse perinatal outcomes, including miscarriage, stillbirth, perinatal mortality, infant mortality, intrauterine growth retardation and low birthweight pre-term delivery. Association between maternal HIV infection and infant mortality was stronger in developing countries and in studies of higher methodological quality.Citation37 Furthermore, severe immuno-suppression was associated with low birthweight neonates, as well as with a trend toward increased risk of pre-term birth.Citation38

Prevention of mother-to-child transmission of HIV

Most vertical transmission of HIV is thought to occur during the weeks prior to delivery (one third of cases) or on the day of delivery (two-thirds of cases), not counting transmission via breastmilk.Citation39 Transmission at earlier stages of pregnancy is believed to occur only seldom. HIV transmission through breastfeeding can take place at any point during lactation, with an increasing cumulative probability the longer the baby is breastfed.Citation40

In the absence of prophylactic intervention, vertical transmission rates are about 20% for HIV-1 and 4% for HIV-2. Several factors, both maternal and fetal, as well as obstetric conditions, have been reported to increase the risk. Most significantly, maternal factors include low peripheral blood CD4+ cell counts and high plasma HIV viral load (though no lower threshold has been associated with absence of risk). In addition, obstetric conditions, such as concurrent genital infections, pre-term delivery and premature rupture of membranes,Citation22 as well as unprotected sex and history of combined injection of cocaine and heroin during pregnancy have also been associated with increased risk of transmission.Citation41Citation42 Birthweight <2500g and HLA class I maternal – neonatal concordance were reported as predictors of HIV perinatal transmission.Citation22

Without intervention, in Africa the rate of HIV transmission from infected mother to infant is very high. Intrauterine transmission rates are estimated at 5–10%, intrapartum transmission rates at 10–20% and through breastfeeding an additional 10–20%. These may vary according to maternal HIV viral load.

In industrialised countries, where HAART, elective caesarean section and replacement feeding are recommended and widely available, vertical transmission rates of less than 3% are common. In most resource-poor countries, HAART is seldom used because of the high cost; as a result of the unavailability of therapy, as well as missed opportunities for HIV testing, HIV MTCT now occurs almost exclusively in resource-poor countries.Citation28

A successful mother-to-child transmission prevention programme involves attendance at an antenatal clinic, HIV testing and counselling, availability of antiretroviral drugs, a return visit for disclosure of HIV test results, acceptance of antiretroviral treatment and correct administration to the woman and infant, and agreement and support to formula-feed the infant if formula is safe and available.Citation22 Women may drop out at each step, hampering overall programme effectiveness. A meta-analysis of Thai and African studies, for example, showed that the mean return rate for test results, regardless of HIV status, ranged widely from 33–100% with a median of 83%.Citation19

Recommended measures for PMTCT include suppression of HIV replication with consequent undetectable plasma viral load during pregnancy and suppression of HIV genital shedding during pregnancy.Citation39 Both of these aims are dealt with by maternal and intrapartum antiretroviral therapy. Moreover, PMTCT measures include elective caesarean section before labour starts and avoidance of breastfeeding with alternative feeding strategies where safe.Citation43Citation44 Evidence from the clinical trial ACTG 076 revolutionised the management of HIV positive women by demonstrating a decrease in vertical transmission among non-breastfeeding women from 25.5% (placebo arm) to 8.3% (antenatal/neonatal zidovudine arm). After this landmark study, other trials showed the effectiveness of abbreviated regimens in the weeks before delivery and/or at delivery and post-partum of various combinations of zidovudine, lamivudine and nevirapine. In addition, a systematic review showed that maternal monotherapy with zidovudine reduces not only the risk of HIV transmission to the infant, but also significantly decreases infant death and maternal death rates.Citation45

Recent WHO guidelines for antiretroviral use during pregnancy take into account whether there are maternal indications for antiretroviral therapy, or if PMTCT is the only reason that therapy is being considered.Citation46 In the former case, adding a single dose of nevirapine (NVP-Sd)

at the onset of labour to the intrapartum and post-partum zidovudine plus lamividine combination, as well as giving babies NVP-Sd within 72 hours of birth, is recommended. Although concern has been raised concerning NVP-Sd use by the infant due to an increased risk of viral resistance, this adverse effect may be avoided by combining nucleoside analogue reverse transcriptase inhibitors to the prescribed antiretroviral regimen,Citation47 or delaying introduction of maternal nevirapine-based antiretroviral therapy until six months after deliveryCitation48 It is important to point out, however, that nevirapine monotherapy for PMTCT is the most affordable or only option in low-resource settings. In these circumstances, in the absence of adequate infrastructure that enables providing combined antiretrovirals, this prophylactic approach may be used.Citation49Although no clinical trial has compared MTCT rates when a woman is on antiretroviral treatment for herself throughout pregnancy, with zidovudine alone or with two other antiretroviral drugs, there is evidence of remarkably low transmission in women on HAART.Citation22 This suggests that worldwide scaling-up of access to antiretroviral treatment to women and men living with HIV whose condition warrants it may by itself be effective in reducing perinatal transmission as well as providing a therapeutic approach for the mother herself and is indeed strongly recommended in spite of the many challenges for implementation.Citation50

An important drawback in the effectiveness of PMTCT relates to patients' lack of adherence to interventions in general and to prescription of antiretroviral therapy in particular, even though adherence to therapy among pregnant women has been shown to be higher than among non-pregnant women.Citation51 Qualitative research has pointed out several barriers to HIV positive women's use or intention to use antiretrovirals during pregnancy, such as fear of toxic effects on the baby or on themselves, fear of drug resistance, belief that prophylactic treatment is unnecessary among “healthy women” and previous birth of a healthy baby without treatment. In contrast, facilitating factors for adherence were women's belief that they owe it to the baby, a positive relationship with the physician, knowing others who have successfully using antiretroviral therapy during pregnancy and previous experience of using it themselves during pregnancy.Citation52

Further limitations in the scaling-up of antiretroviral therapy for PMTCT may include lack of availability of medication within the health care system and insufficient coverage regardless of availability of medication, due to the fact that many women deliver at home or no HIV test or intrapartum treatment is offered.Citation53

Another issue to be addressed is the establishment of health care priorities in an environment of poverty, low education, violence, overall lack of resources, inadequate infrastructure and high prevalence of life-threatening endemic diseases. In a Ugandan survey of people living with HIV, people from the general population, health planners, health workers and people with hypertension, nevirapine use for PMTCT ranked as number five in terms of health care priorities, as compared to treatment for eight other conditions, including treatment for childhood diseases (diarrhoea, pneumonia and malaria) and HAART for people living with HIV. Among these, HAART was ranked number one.Citation54

Delivery care

Women living with HIV should not be kept separate from other women delivering their babies.

A primary goal in public health recommendations for developing countries is to alleviate overall maternal and perinatal morbidity and mortality, including HIV testing, PMTCT and alternatives to breastfeeding where these are available.Citation55 However, for these interventions to be effective, there is an urgent need for improvements in primary health care, maternal and child health care services and skilled attendance at birth, including emergency obstetric care, with active involvement of governments and donor agencies.Citation56

Lack of antenatal care, unavailability or insufficient coverage of HIV testing during pregnancy, or women's refusal to be tested result in a significant number of pregnant women reaching delivery unaware of their HIV status. Delivery itself is another opportunity to diagnose HIV infection, especially with the advent of rapid HIV tests, and may thus provide the necessary access to PMTCT treatment, even though it is the least preferable time for the woman for obvious psychological reasons.

However, denying a woman rapid testing and access to treatment may be worse than her learning she is HIV positive just before delivery. Rapid HIV testing has recently received attention as it is easier to perform and non-laboratory health care staff can be trained to carry it out, making scaling-up of HIV testing more feasible in resource-limited settings.Citation22Citation57 Rapid test results can be ready in less than 30 minutes, enabling prophylactic intervention in pregnant women who test positive at delivery care. Test sensitivity and specificity are very high.Citation58 However these tests may yield false-positive results in screening, particularly in areas where the overall HIV seroprevalence among women is very low. Special attention should thus be given to providing adequate pre-test counselling, obtaining informed consent and ensuring confidentiality of results. Women must be advised that confirmatory serologic evidence of HIV infection is required and should be carried out as part of post-partum care.Citation59

Acceptance of rapid HIV testing antenatally or at delivery has been reported as quite good. In Nairobi, women attending public health clinics were offered either a rapid or a conventional HIV test. Uptake did not differ between the two groups but a higher proportion of women choosing a rapid test actually received their test results. In Thailand, likewise, 79% of women preferred the rapid test method. The further challenge for health care providers is to translate rapid testing uptake into higher treatment uptake.Citation60Citation61

Epidural analgesia is not contraindicated in delivery care of women living with HIV. In contrast, unnecessary rupture of membranes and use of fetal scalp electrodes should be avoided.Citation62

Caesarean sections are safe obstetric procedures and a feasible option in many areas of the world. Elective caesareans should be performed in HIV positive women who present unknown HIV plasma viral loads or viral loads €1,000 copies/mL, preferably during the 38th or 39th gestational week, before onset of labour and membrane rupture, in suitable hospital conditions, so as to minimise the risks of maternal morbidity and mortality.Citation59

In a meta-analysis of the role of elective caesarean delivery for women living with HIV this procedure was shown to significantly decrease the risk of mother-to-child transmission. The association was particularly strong for women who were not on antiretroviral therapy or for those who received zidovudine alone during pregnancy.Citation63 However, post-partum morbidity, including minor (febrile morbidity, urinary tract infection) and major morbidity (endometritis, thromboembolism) was higher after elective caesarean than with vaginal delivery. Risk factors for post-partum morbidity after caesarean delivery among HIV positive women include more advanced HIV disease and conditions such as diabetes.

There is justified concern about recommending caesarean delivery in HIV positive women worldwide, due to associated morbidity, including at subsequent deliveries, whatever the subsequent mode of delivery.Citation22Citation62 Moreover, in terms of PMTCT, caesarean deliveries may be unnecessary for women on HAART who experience suppression of viral replication (<1,000 plasma HIV-RNA copies/mL) or in some cases undetectable viral loads.Citation59 There is recent evidence that in this population caesarean delivery might be associated with increased maternal morbidity.Citation22

In women who deliver vaginally, even though major complications are rare, HIV infection has been associated with an increased risk of puerperal fever, particularly when mediolateral episiotomy is performed.Citation64 The benefit of routine episiotomy for women in general is highly controversial. Evidence from a recent systematic review did not find maternal benefits traditionally ascribed to routine episiotomy, such as prevention of faecal and urinary incontinence or pelvic floor relaxation. In fact, outcomes with episiotomy could be worse, as a proportion of women would have had lesser injury without a surgical incision.Citation65 Among Kenyan women living with HIV, episiotomy or perineal tears and HIV viral loads were found to be independently associated with increased perinatal HIV transmission.Citation66

There is so far no conclusive evidence whether women living with HIV are at increased risk of obstetric complications, as compared to their seronegative counterparts. Though in the developed world HIV infection was initially reported not to be a risk factor for delivery or post-partum complications, including puerperal sepsis, haemorrhagic disorders or anaesthetic side effects,Citation67 in a larger European study a five-fold increased risk of complications was found.Citation64 In resource-constrained settings there is evidence that HIV/AIDS-related maternal deaths are increasing considerably and AIDS has overtaken direct obstetric causes as the leading cause of maternal mortality in some areas of high HIV prevalence.Citation68

An important point to be taken into account is how far HIV positive women are actively participating in decisions concerning delivery. A Brazilian study found that whether giving birth vaginally or by caesarean delivery, the woman's preference took second place to clinical policy. Women reported being advised that caesarean delivery was the only option with HIV; many described their experience of delivery and the post-partum period as more difficult than in previous deliveries and worse than expected.Citation69

For women living with HIV emotional support during pregnancy is certainly important. Whenever possible, women should be allowed to have a companion of their choice present during delivery care. A partner's participation in childbirth may provide psychosocial support for pregnant women during labour and delivery and early father–child bonding, fostering their involvement in raising the child.Citation70Citation71 However, participation is hampered by structural and cultural barriers that include how delivery and fatherhood are perceived, and whether health care providers value male involvement in delivery and infant care.Citation71

Routine incorporation of universal precautions in service delivery is crucial to mitigate occupational risk and reduce fear of infection on the part of health care workers. In a recent Nigerian study with surgeons, obstetricians and gynaecologists, 40% reported needlestick injuries and 26% blood splashs during surgery. All respondents wore protective aprons, but the use of double gloves and protective goggles were reported by 65% and 30% only. Of concern is the fact that 83% of surgeons had reservations about treating patients infected with HIV, while 13% viewed them with fear, although 80% believed HIV positive patients should not be discriminated against, provided necessary protective materials were available.Citation72

Post-partum care

Over half of all maternal deaths occur within the first 24 hours after childbirth and a further 15% during the first week post-partum. All women, including those who deliver outside health care facilities, require care during the post-partum period. Health care providers, however, often tend to advise a first check-up visit six weeks after childbirth, particularly in resource-limited settings. In Kenya, where most women deliver outside a health facility, 81% did not receive post-partum care.Citation73 Lack of knowledge, poverty, cultural beliefs and practices that disregard the need for post-partum care seem to perpetuate the problem. In contrast, if a woman from the same region delivers with the assistance of a skilled birth attendant, she is more likely to seek early post-partum care.Citation74 HIV-related immune suppression may exacerbate these risks.

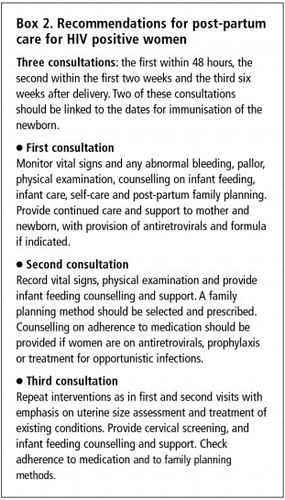

This early period is also critical to enhance infant survival, as most life-threatening newborn illnesses occur in the first week of life. Recommendations for minimal services that a mother and a baby should receive from a skilled attendant after birth are summarised in Box 2.Citation73

Women living with HIV require special care to reduce mammary engorgement, mitigate pain and avoid mastitis. If replacement feeding is chosen by the mother, mechanical breast compression with a bandage is recommended immediately after delivery and should be sustained for ten days. If breast manipulation and stimulation is avoided, this measure may be enough for lactation suppression.Citation75 Supplementary pharmacological intervention when available is indicated if compression cannot be maintained for longer periods. Women who choose to breastfeed should be counselled to avoid it in case of mastitis, since inflammation is associated with increased risk of HIV transmission. Post-partum care of women living with HIV should include prevention of mastitis and rapid treatment of intervening mammary infections.

Clinical and gynaecological follow-up of the mother is needed. Counselling on family planning should be provided and the importance of dual protection emphasised, involving male partners where appropriate. Partners may create significant barriers to adoption of dual protection. Using a breastfeeding alternative may also require support to get family members and community to accept it.

Given that sterilisation is intended to be permanent, special care must be taken to ensure that every woman (and man) makes a voluntary informed choice for it and that the decision is not made in a moment of crisis or depression. Women living with HIV have reported being forced or pressured to accept sterilisation, particularly where sterilisation is prevalent.Citation76 Everyone considering sterilisation, regardless of their HIV status, must understand it is permanent and be informed of alternative contraceptive methods. It is also important to point out that sterilisation provides no protection against STI or HIV acquisition and transmission. Thus, condom use is still recommended even if the need for contraception has been taken care of.Citation77–79 National laws and norms for sterilisation must be considered in the decision. An AIDS-related illness may require the procedure to be delayed.

Post-partum care must integrate obstetric care and HIV specialists, to ensure continuity of antiretroviral treatment for the woman, where indicated. Special attention should be given to counselling on the stresses and demands of caring for a new baby, checking for signs of depression and promoting adherence to therapy.Citation80

Infant feeding

Despite recent advances in reducing pregnancy-related HIV transmission to infants with the use of antiretrovirals, there is still a critical need to make infant feeding safer. Appropriate social support for cup feeding and other feeding options that reduce the risk of transmitting HIV while ensuring adequate nutrition should be considered a priority by infant care providers and at community level. Current recommendations stress avoidance of breastfeeding if replacement feeding meets the requirements of being affordable, feasible, acceptable, sustainable and safe. Otherwise, exclusive breastfeeding followed by early weaning is recommended.Citation81

In resource-poor settings, particularly in Africa, where requirements may be lacking, many HIV positive women are either choosing to breastfedCitation82Citation83 or feel they have little actual choice due to lack of clean water, affordable milk powder or both. In these regions lack of access to quality primary health care is also an issue that hinders the appropriate management of frequent and often severe replacement feeding-related morbidity. Therefore local epidemiological data on health risks for both mother and child are important in decision-making.Citation84 Tailoring policy recommendations with established algorithms that identify the healthiest feeding choices for the local environment is a good approach. Mathematical modelling, including infant mortality rates, has been used to estimate the impact of different infant feeding options on HIV-free survival. Results suggest that in settings where infant mortality is below 25 per 1000 live births, replacement feeding from birth results in the greatest HIV-free survival to 24 months, depending on the amount of support, whereas exclusive breastfeeding up to six months of age followed by early weaning produces the best outcome where infant mortality exceeds 25 per 1000 live births. Replacement feeding results in lower HIV-free survival, as compared to non-exclusive breastfeeding in areas with the highest infant deaths (>101 per 1000 live births).Citation85

Type of breastfeeding probably plays an important role in post-natal HIV transmission. A few studies in the past suggested that exclusive breastfeeding, i.e. breastmilk only with no other food or fluid, might be associated with HIV transmission rates which were lower than in mixed-fed infants (those who received breastmilk and other fluids).Citation86Citation87 Mixed feeding is believed to increase gut permeability and induce mucosal inflammation, facilitating HIV acquisition. More recently, however, conflicting results have questioned even the relative safety of exclusive breastfeeding. In Zimbabwe, early mixed feeding was associated with a four-fold higher risk of HIV when compared to exclusive breastfeeding.Citation88 In contrast, in Uganda exclusive breastfeeding and mixed feeding resulted in similar risks of HIV transmission, and both yielded higher rates of transmission compared to formula feeding.Citation89

Infant feeding decisions are not only difficult to make but also to sustain at community level.Citation90 25% of Ugandan women who had chosen exclusive breastfeeding actually gave other food to their infants and 11% of those who had chosen replacement feeding reported having breastfed their babies at least once, probably because of social pressure.Citation89

In addition, qualitative research in Malawi showed that HIV positive mothers' perception of their own bodies and health influenced their infant feeding practices. Women perceived larger body sizes as healthier, were worried that their nutritional status (body size) was declining because of their illness and feared breastfeeding might increase the progression of HIV disease. These results point to the need for more comprehensive information for women, focusing on the woman's health and well-being as well as the infant's.Citation91

Women's and men's beliefs and attitudes towards infant feeding options may strongly influence their choices in the context of PMTCT. In Côte d'Ivoire, the vast majority of mothers and mothers-to-be regarded breastfeeding as the appropriate method, but exclusive breastfeeding was not well accepted. Water, especially, was felt a necessary supplement for infants, and wet nursing was accepted by only a few mothers.Citation92

Informed choice of infant feeding method by HIV positive women, as recommended by UNAIDS/WHO/UNICEF guidelines, may also be compromised by limited counsellor training. In-depth interviews with Tanzanian HIV/AIDS counsellors indicate lack of knowledge or confusion about the actual risks and benefits of the different infant feeding options, counsellors falling back on directive counselling and lack of follow-up support to mothers as important barriers to good quality advice.Citation93

With formula-feeding, in the absence of perinatal antiretroviral treatment, evidence from a randomised trial in Kenya indicated 20.5% of HIV infection in the formula-fed infants as compared to 36.7% in the breastfed group.Citation94 Though the women had access to a clean water supply and could make the formula safely, mortality at 24 months of age was very high and did not differ between breastfed and non-breastfed infants. Formula-feeding in this population was shown to prevent babies from acquiring HIV but not from dying of other causes.Citation95

There is concern among breastfeeding advocates that in resource-poor communities, increased use of formula-feeding by HIV positive mothers might spill over to uninfected mothers, undermining years of public health messages about the benefits of breastfeeding as a complete source of nutrition for infants, bonding, stimulating infant cognitive development and prolonging post-partum amenorrhoea to support child spacing. However, the complexity of the choice whether to breastfeed for HIV positive women remains one with compelling benefits and risks on both sides.

Safer breastfeeding has been proposed for HIV positive women who choose to breastfeed.Citation95 This involves expressing and pasteurising breastmilk. The sustainability of this practice is uncertain, since it is not only less convenient, more time-consuming and more expensive in terms of fuel, but also may be as strongly associated with stigma and discrimination as avoiding breastfeeding altogether.

Breastfeeding by women on HAART may decrease stigma, increase quality of life of HIV positive parents, contribute to parenting efforts, decrease child mortality and perhaps help to motivate people in the community to present for HIV testing and counselling, creating increased awareness about HIV.Citation26 The goal is to provide HAART to people living with HIV in need, whereas giving antiretrovirals in the peri-partum period only to prevent MTCT is a short-term measure.

Infant care

The impact of the HIV epidemic on child health globally is a major emerging issue. Before large-scale national PMTCT programmes began to be implemented, 600,000 new paediatric infections were estimated to occur annually, particularly in Africa.Citation96 Whereas children account for only 4% of people living with HIV, 20% of AIDS deaths have been in children.Citation97

Immaturity of the immune system is believed to affect an infant's ability to combat HIV infection. Consequently, perinatally infected children generally progress to AIDS more rapidly than HIV positive adults.Citation97 In the pre-HAART era, approximately 25% of these children progressed to AIDS within the first year of life and the median time to AIDS development for the remaining 75% was seven years. Prognosis is still dramatic for children living in poor countries; over 50% die within two years and 89% by the age of three in sub-Saharan Africa.Citation96Citation98

However, coordinated perinatal and paediatric HIV care initiatives have been shown to be effective. In a successful collaborative programme, Jamaican nurses and midwives were trained in PMTCT, voluntary counselling and testing, and recognition and management of paediatric AIDS, following guidelines for HIV care with consequent impact on sensitising and encouraging other health care workers in the care of persons living with HIV/AIDS, on enhancing multidisciplinary collaboration, on sensitising people in the community about the disease and on improving the comfort level of women and families with accessing health care.Citation99

Early diagnosis of HIV infection is crucial for HIV positive children. However, difficulties still exist in many areas of the globe, particularly where access to antenatal and delivery care is deficient, which postpone recognition of vertically transmitted infection. Suspicion of HIV infection should target not only infants born to HIV positive mothers, but also those who exhibit clinical signs of immune suppression. The aim is to recognise HIV infection as early as possible, to prevent opportunistic infections and HIV disease progression and address psychosocial issues that might impair the child's development.Citation100 This includes HIV serologic monitoring until 18 months of age to rule out infection; this may also be done with two negative HIV virological tests at ages one and four months.Citation22 Recently, HIV-RNA detection on dried blood spots on filter paper was assessed in South Africa, yielding high diagnostic sensitivity and specificity.Citation101 This approach may allow early diagnosis of HIV infection in areas where molecular biology laboratories are not widespread. Cotrimoxazole prophylaxis (for Pneumocystis pneumonia but also other bacteriological diseases) after the age of six weeks for at least four months, regardless of negative viral results, is also recommended. Clinical and laboratory monitoring of the child's growth and development should include screening for other perinatal infections and immunisation, as well as checking for evidence of zidovudine-associated anaemia.

Developing effective infant care strategies continues to be a significant challenge. So far, most initiatives relating to children have been to reduce perinatal transmission, without providing any other intervention to mothers, their partners or children.Citation28 As a consequence, infected and non-infected children born to HIV positive parents have often faced being placed in an orphanage – hardly an effective, long-term solution. Implementation of a more comprehensive approach to the care of affected families and keeping parents alive and healthy is urgently needed if these children are to have a future.

The family situation has been reported as an important barrier to proper care of infants living with HIV in Thailand.Citation102 Two years after birth, three times more women were shown to be living alone, as compared to the time of delivery; 30% of families had a reduced income and 10% of male partners had died. Most children (78%) were living with their mothers, but only 57% of mothers were their children's primary caretakers. Furthermore, high levels of depression were identified among women living with HIV, particularly with regard to their children's health and family's future.

Children and adolescents living with HIV and adoption

For care providers and HIV positive parents, the long-term care of their children, including those living with HIV who are growing into adolescence under HAART, is important. Support is needed by HIV-affected families and should thus be more deeply considered in the comprehensive care provided to women and men living with HIV.Citation21,72,103

Recent studies conducted among adolescents who were born with HIV or who acquired HIV after sexual exposure have highlighted important challenges to be faced when linking HIV and AIDS care and sexual and reproductive health.Citation103–105 Children infected through their mothers tended to grow up over-protected, often without being told they have HIV, and many lack basic information about sexuality and reproduction until late adolescence. In contrast, at the same ages, those who were sexually infected suffer from stigma and discrimination at health care centres. Developmental issues with many of these adolescents have been disregarded and their HIV positive status disclosed without their consent, even when it was unnecessary as regards their care needs. The future role of pregnant girls as mothers is also often overlooked during antenatal visits. In addition, adolescents living with HIV are very concerned about their bodies and body image as related to their health status; the emotional suffering of keeping their HIV status secret is a terrible burden. They need psychosocial support to be able to disclose their diagnosis to friends and loved ones and to make plans for the future, including having a sexual relationship, building a family and having children.Citation105

Some HIV positive adolescents see adoption of children as an alternative to having their own children.Citation103 Many orphans who are living with HIV have themselves been legally or unofficially adopted by foster families worldwide. Nevertheless, when they reach adolescence, they may not be permitted to do the same, as governmental regulations in many countries prohibit adoption by people living with HIV.Citation106

Particularly in Africa, orphanhood is a neglected issue. For orphan care, the community-based approach is usually preferred since it maintains the affected child within a family environment in their own village or tribe.Citation107 Fostering of orphaned infants by the extended family often means by elderly relatives; often they cannot afford to support the children or refuse to do so due to stigma and discrimination.

In some developing countries, when a parent dies, older children may be the only surviving family members to care for younger siblings. Foster care for children or the future of those who have lost one or both parents may differ in different cultural contexts.Citation108 Being HIV positive and either losing their mother or both parents to AIDS increases a child's chance of being institutionalised in Brazil.Citation109 Consequently, young children without either parent should be given the highest priority.

In 2005, Human Rights Watch documented the extent to which children suffer discrimination in access to education from the moment HIV afflicts their families.Citation110 Children may have to leave school to perform household labour or to mourn a parent's death. Many cannot afford school fees if parents are too sick to earn a living, and schools may even refuse admission to HIV-affected children. In many cases, their mothers were left with no resources after their husbands died of AIDS. In others, volunteers from community-based organisations resorted to pooling meagre resources to provide orphans only with basic necessities. Many orphans live in the street or in households headed by other children. Qualitative research with HIV positive Nigerians, community leaders and AIDS orphans showed that the burden of childcare often fell on maternal family members. Poor education, due to lack of finances, ranked highest among the problems these children faced. A need was highlighted for the government to support and network with NGOs to provide HIV care and family support for orphans.Citation111 International agencies also have an important role in this regard, providing technical advice and funding.Citation112

Policy implications

Men and women living with HIV face difficult choices concerning sexuality, parenthood desires and family life. Structural, social and cultural issues, as well as the lack of programmatic support, hinder the fulfilment of their rights to quality sexual and reproductive health care and to have a family. In a study that investigated issues of sexuality and reproduction, 250 men living with HIV in São Paulo, Brazil, were asked whether they wished to have children and whether health professionals in the HIV/AIDS care clinics that they attended were supportive of their wishes. Most participants said that professionals were not supportive enough or even impartial about HIV positive people having children, and paid little attention to men's fathering role. 80% of the men had sexual relationships, and 43% of them wanted children, especially those who had no children, in spite of expectations of disapproval. Few of the men received information about treatment options that would protect infants, however. In previous studies with HIV positive women attending the same clinics, by comparison, greater knowledge about prevention of perinatal HIV transmission was reported, but women had fewer sexual relationships, fewer desired to have children, and they expected even more disapproval of having children from health professionals.Citation5 Similar expectations concerning having a child and anticipating disapproval from health care providers, as well as lack of updated information on PMTCT have been reported by heterosexual men living with HIV in London.Citation113 These studies suggest that the rights of people with HIV to found a family depend as much on curing the ills of prejudice and discrimination, including among health professionals, as on medical interventions.

Policies aiming at protecting and fulfilling the rights of men and women living with HIV to

parenthood should thus be comprehensive enough to address the continuum of care from pregnancy to infant and child care, to provide means of integrating sexual and reproductive health interventions with HIV/AIDS care and to mitigate AIDS-related stigma and discrimination.Skilled care, defined as the continuum of care from community and primary level to tertiary levelCitation114 for HIV positive women and men in relation to parenthood must go beyond provision of the best treatment available and foster multi-sectoral links with the education system, community-based organisations and social movements that cope with a broad range of AIDS-related burdens, especially in high prevalence areas. Focusing on the couple, the individual or the set of adults who are responsible for raising children, rather than seeing only the woman or the infant as the unit of care, would certainly be an innovative programmatic advance towards meeting the parenthood rights and needs of people living with or affected by HIV.

Notes

* Access to HIV testing is lacking in parts of Eastern Europe, Latin America and Africa. In some countries, voluntary testing and counselling centres are available in most large urban centres but not rural ones.

References

- B Zaba, S Gregson. Measuring the impact of HIV on fertility in Africa. AIDS; 12(Suppl.1), 1998:341-350.

- JR Glynn, A Buve, M Carael. Decreased fertility among HIV-1 infected women attending antenatal clinics in three African cities. Journal of the Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome; 25(4), 2000:345-352.

- JL Chen, KA Philips, DE Kanouse. Fertility desires and intentions of HIV positive men and women. Family Planning Perspectives; 33(4), 2001:144-152.

- A Castro, P Farmer. Understanding and addressing AIDS-related stigma: from anthropological theory to clinical practice in Haiti. American Journal of Public Health; 95(1), 2005:53-59.

- V Paiva, N Santos, I FrançaJr. Desire to have children, gender and reproductive rights of men and women living with HIV: a challenge to health care in Brazil. AIDS Patient Care and STDs; 21(4), 2007:268-277.

- LM Kopelman, AA van Niekerk. AIDS and Africa - Introduction. Journal of Medical Philosophy; 27(2), 2002:139-142.

- V Paiva, E Ventura-Felipe, N Santos. The right to love: the desire for parenthood among men living with HIV. Reproductive Health Matters; 11(22), 2003:91-100.

- M. de Bruyn. Living with HIV: challenges in reproductive health care in South Africa. African Journal of Reproductive Health; 8(1), 2004:92-98.

- INFO Project. Pesquisas com Homens: Novos Resultados. Population Reports; 32(2), 2004 Série M, No.18. At: <www.bibliomed.com.br. >.

- E Clift. Redefining macho: men as partners in reproductive health. Perspectives in Health; 2(2), 1997:20-25.

- P Sternberg, J Hubley. Evaluating men's involvement as a strategy in sexual and reproductive health promotion. Health Promotion International; 19(3), 2004:389-396.

- UNAIDS/ 01.64E, Working with men for HIV prevention and careOctober 2001, UNAIDS. Geneva.

- UNAIDS/ 02.31E, Keeping the promise. Summary of the Declaration of Commitment on HIV/AIDS. United Nations General Assembly Special Session on HIV/AIDS (UNGASS), 25–27 June 2001June 2002, UNAIDS. Geneva.

- VR Bhalerao, M Galwankar, SS Kowli. Contribution of the education of the prospective fathers to the success of maternal health care programme. Journal of Postgraduate Medicine; 30(1), 1984:10-12.

- CL Varkey, A Mishra, A Das Involving Men in Maternity Care in India. FRONTIERS Final Report. 2004, Population Council. Washington, DC. At: <www.popcouncil.org/pdfs/frontiers/FR FinalReports/Indi MIMpdf. >.

- M Brase, R Dinglasan, M Ho UNICEF/Yale School of Public Health Research Project: The Role of Men in Families. 1997, Yale University School of Medicine, International Health Department. New Haven.

- MZ Goldani, ERJ Giugliani, T Scanlon. Voluntary HIV counseling and testing during prenatal care in Brazil. Revista de Saúde Pública; 37(5), 2003:552-558.

- SD Almeida, MB Barros. Equity and access to health care for pregnant women in Campinas (SP), Brazil. Revista Panamericana de Salud Pública; 17(1), 2005:15-25.

- M Cartoux, N Meda, P Van de Perre. Acceptability of voluntary HIV testing by pregnant women in developing countries: na international survey. Ghent International Working Group on Mother-to-Child transmission of HIV. AIDS; 12(18), 1998:2489-2493.

- JD Ruiz, F Molitor. Knowledge of treatment to reduce perinatal human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) transmission and likelihood of testing for HIV: results from 2 surveys of women of childbearing age. Maternal and Child Health Journal; 2(2), 1998:1117-1122.

- IPAS, Reproductive rights for women affected by HIV/AIDS. 2005 At: <www.ipas.org/english/publication/international_health_policies.asp. >.

- D Cohan. Perinatal HIV: special considerations. Topics in HIV Medicine; 11(6), 2003:200-213.

- KE O'Connor, SE MacDonald. Aiming for zero: preventing mother-to-child transmission of HIV. Canadian Medical Association Journal; 166(7), 2002:909-910.

- KA Workowski, SM Berman. Sexually-transmitted diseases treatment guidelines: 2006. Recommendation Report. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report; 55(RR11), 2006:1-94.

- MG Kiddugavu, N Kiwanuka, MJ Wawer. Effectiveness of syphilis treatment using azythromycin and/or benzathine penicillin in Rukai, Uganda. Sexually Transmitted Diseases; 32(1), 2005:1-6.

- MD Andersen, GA Smereck, EM Hockman. Nurses decrease barriers to health care by “hyperlinking” multiple-diagnosed women living with HIV/AIDS into care. Journal of the Association of Nurses in AIDS Care; 10(2), 1999:55-65.

- Mullick S, Kunene B, Wanjiru M. Involving men in maternity care: health service delivery issues. Agenda: Special Focus on Gender, Culture and Rights (Special issue):124–35. At: <www.popcouncil.org/frontiers>..

- R Colebunders, P Kolsteren, R Ryder. Giving anitiretrovirals in the peripartum period to prevent mother-to-child HIV transmission in low-income countries: only a short-term stopgap measure. Tropical Medicine and International Health; 8(5), 2003:375-377.

- J Manchester. Perinatal HIV transmission and children affected by HIV/AIDS: concepts and issues. AIDS/STD Health Promotion Exchange4), 1997:1-4.

- K Semrau, L Kuhn, C Vwalika. Women in couple antenatal HIV counseling and testing are not more likely to report adverse social events. AIDS; 19(6), 2005:603-609.

- S Maman, J Campebell, MD Sweat. The intersections of HIV and violence: directions for future research and interventions. Social Science and Medicine; 50(4), 2000:459-478.

- WHO, Violence against women and HIV. 2004 At: <www.who.int/gender/violence/en/vawinformationbrief.pdf. >.

- S Zierler, B Witbeck, K Mayer. Sexual violence against women living with or at risk for HIV infection. American Journal of Preventive Medicine; 12(5), 1996:304-310.

- C Retzlaff. Women, violence and health care. AIDS Care; 5(3), 1999:40-45.

- RL Sowell, KD Phillips, B Seals. Incidence and correlates of physical violence among HIV-positive women at risk for pregnancy in southeastern United States. Journal of the Association of Nurses in AIDS Care; 13(2), 2002:46-58.

- B Mawn. Integrating women's perspectives on prenatal human immunodeficiency virus screening: towards a socially just policy. Research in Nursing & Health; 21(6), 1998:499-509.

- P Brocklehurst, R French. The association between maternal HIV infection and perinatal outcome: a systematic review of the literature and meta-analysis. British Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology; 105(8), 1998:836-848.

- ET Abrams, DA MilnerJr, J Kwiek. Risk factors and mechanisms of preterm delivery in Malawi. American Journal of Reproductive Immunology; 52(2), 2004:174-183.

- C Rouzioux, M-L Chaix, M Burgard. HIV and pregnancy. Pathologie biologie; 502002:576-579.

- G John-Stewart, D Mbori-Ngacha, R Ekpini. Breast-feeding and transmission of HIV-1. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome; 35(2), 2004:196-202.

- PB Matheson, PA Thomas, EJ Abrams. Heterosexual behavior during pregnancy and perinatal transmission of HIV-1. New York City Perinatal HIV Transmission Collaborative Study Group. AIDS; 10(11), 1996:1249-1256.

- M Bulterys, S Landesman, DN Burns. Sexual behavior and injection drug use during pregnancy and vertical transmission of HIV-1. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes and Human Retrovirology; 15(1), 1997:76-82.

- European Mode of Delivery Collaboration. Elective caesarean section versus vaginal delivery in prevention of vertical HIV-1 transmission: a randomized clinical trial. Lancet; 353(9158), 1999:1035-1039.

- L Mandelbrot, J Le Chenadec, A Berrebi. Perinatal HIV-1 transmission: interaction between zidovudine and mode of delivery in the French Perinatal Cohort. Journal of American Medical Association; 280(1), 1998:55-60.

- P Brocklehurst, J Volmink. Antiretrovirals for reducing the risk of mother-to-child transmission of HIV infection. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews2), 2002:CD003510.

- WHO. Antiretroviral drugs for treating pregnant women and preventing HIV infection in infants: towards universal access: recommendations for a public health approach–2006 version. At: <www.who.int/hiv/pub/guidelines/pmtct/en/index.html. >.

- J McIntyre. Controversies in the use of nevirapine for the prevention of mother-to-child transmission of HIV. Expert Opinion on Pharmacotherapy; 7(6), 2006:677-685.

- S Lockman, RL Shapiro, LM Smeaton. Response to antiretroviral therapy after a single peripartum dose of nevirapine. New England Journal of Medicine; 356(2), 2007:135-147.

- TE Taha, NI Kumwenda, DR Hoover. Nevirapine and zidovudine at birth to reduce perinatal transmission of HIV in an African setting: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA; 292(2), 2004:202-209.

- F Dabis, L Bequet, DK Ekouevi. Field efficacy of zidovudine, lamivudine and single-dose nevirapine to prevent peripartum HIV transmission. AIDS; 19(3), 2005:309-318.

- CD Zorrilla, LE Santiago, D Knubson. Greater adherence to highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART) between pregnant versus non-pregnant women living with HIV. Cellular and Molecular Biology (Noisy-le-grand); 49(8), 2003:1187-1192.

- K Siegel, HM Lekas, EW Scrimshaw. Factors associated with HIV-infected women's use or intention to use AZT during pregnancy. AIDS Education and Prevention; 13(3), 2001:189-206.

- M Temmerman, A Quaghebeur, F Mwanyumba. Mother-to-child HIV transmission in resource poor settings: how to improve coverage?. AIDS; 17(8), 2003:1239-1242.

- L Kapiriri, B Robbestad, OF Norheim. The relationship between prevention of mother to child transmission of HIV and stakeholder decision making in Uganda: implications for health policy. Health Policy; 66(2), 2003:199-211.

- F Dabis, ML Newell, L Fransen. Prevention of mother-to-child transmission of HIV in developing countries: recommendations for practice. The Ghent International Working Group on Mother-to-Child Transmission of HIV. Health Policy and Planning; 15(1), 2000:34-42.

- J Liljestrand. Strategies to reduce maternal mortality worldwide. Current Opinion in Obstetrics and Gynecology; 12(6), 2000:513-517.

- K Kanal, TL Chou, L Sovann. Evaluation of the proficiency of trained non-laboratory health staff and laboratory technicians using a rapid and simple HIV antibody test. AIDS Research and Therapy; 2(1), 2005:5.

- AV Bhore, J Sastry, D Patke. Sensitivity and specificity of rapid HIV testing of pregnant women in India. International Journal of STD and AIDS; 14(1), 2003:37-41.

- Ministry of Health, Brazil. Programa Brasileiro de DST/AIDS. [Brazilian Guidelines for delivery care] Brasília: 2004. At: <www.aids.gov.br/final/biblioteca/gestante_2004/ConsensoGestante2004.doc. >.

- A Liu, PH Kilmarx, S Supawitkul. Rapid whole-blood finger-stick test for HIV antibody: performance and acceptability among women in northern Thailand. Journal of the Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome; 33(2), 2003:194-198.

- IM Malonza, BA Richardson, JK Kreiss. The effect of rapid HIV-1 testing on uptake of perinatal HIV-1 interventions: a randomized clinical trial. AIDS; 17(1), 2003:113-118.

- DR Burdge, DM Money, JC Forbes. Canadian consensus guidelines for the management of pregnancy, labour and delivery and for postpartum care in HIV-positive pregnant women and their offspring. Canadian Medical Association Journal; 168(13), 2003:1671-1674.

- JS Read, ML Newell. Efficacy and safety of caesarean delivery for prevention of mother-to-child transmission of HIV-1. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews4), 2005:CD005479.

- S Fiore, ML Newell, C Thorne. Higher rates of post-partum complications in HIV-positive than in uninfected women irrespective of mode of delivery: European HIV in Obstetrics Group. AIDS; 18(6), 2004:933-938.

- K Hartmann, M Viswanathan, R Palieri. Outcomes of routine episiotomy: a systematic review. JAMA; 293(17), 2005:2141-2148.

- JG Ayisi, AM van Eijk, RD Newman. Maternal malaria and perinatal HIV transmission, Western Kenya. Emerging Infectious Diseases [serial online] April 2004. At: <www.cdc.gov/ncidod/EID/vol10no4/03-0303.htm. >.

- H Minkoff. HIV and pregnancy. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology; 1731995:585-589.

- J McIntyre. Maternal health and HIV. Reproductive Health Matters; 13(25), 2005:129-135.

- DR Knauth, RM Barbosa, K Hopkins. Between personal wishes and medical prescription: mode of delivery and post-partum sterilisation among women with HIV in Brazil. Reproductive Health Matters; 11(22), 2003:113-121.

- AM Bien, GJ Iwanowicz-Palus, G Stadnicka. Involvement of men in parenthood. Wiadomosci Lekarskie (Warsow, Poland: 1960); 55(Suppl.1), 2002:26-33.

- ML De Carvalho. Fathers' participation in childbirth at a public hospital: institutional difficulties and motivations of couples. Cadernos de Saúde Pública; 19(Suppl.2), 2003:S389-S398.

- SN Obi, P Waboso, BC Ozumba. HIV/AIDS: occupational risk, attitude and behaviour of surgeons in southeast Nigeria. International Journal of STD and AIDS; 16(5), 2005:370-373.

- Population Council, Repositioning Post Partum Care in Kenya. 2005 At: <www.popcouncil.org/pdfs/Safe_Mom_Postpatum_Care.pdf. >.

- Population Council, SMDP Western Province. Approaches to providing quality maternity care in Kenya. University of Nairobi. 2004.

- NK Kochenour. Lactation suppression. Clinics in Obstetrics and Gynaecology; 23(4), 1980:1045-1059.

- N Santos, E Ventura-Felipe, V Paiva. HIV positive women, reproduction and sexuality in São Paulo, Brazil. Reproductive Health Matters; 6(12), 1998:31-40.

- Centers for Disease Control. Surgical sterilization among women and use of condoms: Baltimore, 1989–1990. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report 1992;41(31):568–69;575..

- RM Barbosa, T do Lago, S Kalckman. Sexuality and reproductive health care in São Paulo, Brazil. Health Care for Women International; 17(5), 1996:413-421.

- RM Barbosa, WV Villela. Sterilisation and sexual behaviour among women in São Paulo, Brazil. Reproductive Health Matters; 3(5), 1995:37-46.

- CDC. Recommendations for use of antiretroviral drugs in pregnant HIV-1-infected women for maternal health and interventions to reduce perinatal HIV-1 transmission in the United States. Health Services/Technology Assessment Text (HSTAT) Series. At: <www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/bv.fcgi?rid=hstat. >.

- WHO/UNICEF/UNAIDS/UNFPA. HIV and infant feeding. Guidelines for decision-makers. Geneva: 2003. At: <www.who.int/child-adolescent-health/new-publication/NUTRITION/HIV_IF_DM.pdf. >.

- AA Omari, C Luo, C Kankasa. Infant-feeding practices of mothers of known HIV status in Lusaka, Zambia. Health Policy and Planning; 18(2), 2003:156-162.

- JN Kiarie, BA Richardson, D Mbori-Ngacha. Infant-feeding practices of women in a perinatal HIV-1 prevention study in Nairobi, Kenya. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome; 35(1), 2004:75-81.

- AV Shankar, J Sastry, A Erande. Making the choice: the translation of global HIV and infant feeding policy to local practice among mothers in Pune, India. Journal of Nutrition; 135(4), 2005:960-965.

- EG Piwoz, JS Ross. Use of population-specific mortality rates to inform policy decisions regarding HIV and infant feeding. Journal of Nutrition; 135(5), 2005:1113-1119.

- A Coutsoudis, K Pillay, E Spooner. Influence of infant-feeding patterns on early mother-to-child transmission of HIV-1 in Durban, South Africa: a prospective cohort study. Lancet; 354(9177), 1999:471-476.

- A Coutsoudis, K Pillay, L Kuhn. Method of feeding and transmission of HIV-1 from mothers to children by 15 months of age: prospective cohort study from Durban, South Africa. AIDS; 15(3), 2001:379-387.

- PJ Iliff, EG Piwoz, NV Tavengwa. Early exclusive breastfeeding reduces the risk of postnatal HIV-1 transmission and increases HIV-1 free survival. AIDS; 19(7), 2005:699-708.

- M Magoni, L Bassani, P Okong. Mode of infant feeding and HIV infection in children in a program for prevention of mother-to-child transmission in Uganda. AIDS; 19(4), 2005:433-437.

- RL Shapiro, S Lockman, I Thior. Low adherence to recommended infant feeding strategies among HIV-positive women: results from a pilot phase of a randomized trial to prevent mother-to-child transmission in Botswana. AIDS Education and Prevention; 15(3), 2003:221-230.

- ME Bentley, AL Corneli, E Piwoz. Perceptions of the role of maternal nutrition in HIV-positive breast-feeding women in Malawi. Journal of Nutrition; 135(4), 2005:945-949.

- EA Yeo, L Béquet, DK Ekouévi. Attitudes towards exclusive breastfeeding and other infant feeding options – a study from Abidjan, Côte d'Ivoire. Journal of Tropical Pediatrics; 51(4), 2005:223-226.

- MM de Paoli, R Manongi, KI Klepp. Counsellors' perspectives on antenatal HIV testing and infant feeding dilemmas facing women with HIV in northern Tanzania. Reproductive Health Matters; 10(20), 2002:144-156.

- R Nduati. Breastfeeding and HIV-1 infection. A review of current literature. Advances in Experimental Medicine and Biology; 4782000:201-210.

- S Filteau. Infant-feeding strategies to prevent post-natal HIV transmission. Transactions of the Royal Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene; 97(1), 2003:25-29.

- P Vaz, N Elenga, P Fassinou. HIV infection in children in African countries. Medicine Tropicale; 63(4–5), 2003:465-472.

- PJR Goulder, P Jeena, G Tudor-Williams. Paediatric HIV infection: correlates of protective immunity and global perspectives in prevention and management. British Medical Bulletin; 582001:89-108.

- TE Taha, SM Graham, NI Kumwenda. Morbidity among human immunodeficiency virus-1-infected and uninfected African children. Pediatrics; 106(6), 2000:1-8.

- PM Palmer, MM Anderson-Allen, CC Billings. Nursing interventions in the Kingston Paediatric and Perinatal HIV/AIDS Programme in Jamaica. West Indian Medical Journal; 53(5), 2004:327-331.

- AH Krist, A Crawford-Faucher. Management of newborns exposed to maternal HIV infection. American Family Physician; 65(10), 2002:2061-2062.

- GG Sherman, G Stevens, SA Jones. Dried blood spots improve access to HIV diagnosis and care for infants in low-resource settings. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome; 38(5), 2005:615-617.

- C Manopaiboon, N Shaffer, L Clark. Impact of HIV on families of HIV-positive women who have recently given birth, Bangkok, Thailand. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes and Human Retrovirology; 18(1), 1998:54-63.

- JR Ayres, V Paiva, I FrançaJr. Vulnerability, human rights and comprehensive care of young people living with HIV/AIDS. American Journal of Public Health; 96(6), 2006:1001-1006.

- JR Ayres, A Segurado, E Galano Adolescentes e jovens vivendo com HIV/AIDS: cuidado e promoção da saúde no cotidiano da equipe multi- profissional. Aids Novos HorizontesMaio 2004, Office Editora e Publicidade. São Paulo35.

- H Aka Dago-Akribi, M-C Cacou Adjoua. Psychosocial development among HIV-positive adolescents in Abidjan, Côte d'Ivoire. Reproductive Health Matters; 12(23), 2004:19-28.

- M de Bruyn. Women, reproductive rights and HIV/AIDS: Issues on which research and intervention are still needed. Journal of Health, Population and Nutrition; 24(4), 2006 At: <www.icddrb.org/images/Forthcoming_Women-reproductive.pdf. >.

- BJ Beard. Orphan care in Malawi: current practices. Journal of Community Health Nursing; 22(2), 2005:105-115.

- L Taylor. Patterns of child fosterage in rural northern Thailand. Journal of Biosocial Science; 37(3), 2005:333-350.

- M Doring, I França-Junior, I Stella. Factors associated with institutionalization of children orphaned by AIDS in a population-based survey in Porto Alegre, Brazil. AIDS; 19(Suppl.4), 2005:S59-S63.

- Human Rights Watch, Letting Them Fail. Government Neglect and the Right to Education for Children Affected by AIDS. 2005 At: <hrw.org/reports/2005/africa1005. >.

- MO Folayan, I Fakande, EO Ogunbodede. Caring for the people with HIV/AIDS and AIDS orphans in Osun State: a rapid survey report. Nigerian Journal of Medicine; 10(4), 2001:177-181.

- A Bhargava, B Bigombe. Public policies and the orphans of AIDS in Africa. BMJ; 326(7403), 2003:1387-1389.

- L Sherr, N Barry. Fatherhood and HIV-positive heterosexual men. HIV Medicine; 5(4), 2004:258-263.

- WHO/ICM/FIGO, Making pregnancy safer: the critical role of the skilled attendant: a joint statement by WHO, ICM and FIGO. 2004.