Abstract

Six months after a Comprehensive Abortion Care project was implemented in Phụ-Sàn Hospital, the main maternity hospital in Hài Phòng, northern Viet Nam, a study of quality of abortion services was carried out. The study explored the interaction between providers and women seeking abortion and how cultural values influenced quality of care. A quantitative and qualitative approach was employed: a three-part structured survey with 748 women before and after they had an abortion, 20 in-depth interviews with women just after abortion, seven informal interviews with health care staff and 100 participant observations. Both the women and the staff equated quality of care mainly with improved technical performance of abortion. Insufficient knowledge and skills had a negative impact on provision of information and good quality counselling in relation to understanding and uptake of contraception, treating reproductive tract infection and preventing post-abortion infection. To further improve abortion care in hospitals such as Phụ-Sàn, training programmes are needed that integrate counselling and clinical skills and address the cultural factors that hinder health staff and women from interacting in an equitable manner. A supportive supervisory system that holds health staff accountable for conducting high quality information and counselling sessions should also be established.

Résumé

Une étude de qualité a porté sur un projet de soins globaux pour avortement six mois après son lancement à l'hôpital de Phu-San, principale maternité d'Hai Phong, au nord du Viet Nam. L'étude a analysé l'interaction entre les prestataires de soins et les femmes ayant demandé un avortement, et l'influence des valeurs culturelles sur la qualité des services. Elle a utilisé une approche quantitative et qualitative : une enquête structurée en trois parties auprès de 748 femmes avant et après l'avortement, 20 entretiens avec des femmes venant d'avorter, sept entretiens avec des personnels de santé et 100 observations de participants. Aussi bien pour les femmes que pour le personnel, la qualité des soins était synonyme d'amélioration de la pratique technique de l'avortement. Le manque de connaissances et de compétences contrariait la diffusion des informations et l'apport de conseils de qualité sur la compréhension de la contraception ainsi que l'adoption d'une méthode, le traitement des infections gynécologiques et la prévention des infections post-avortement. Pour améliorer les services d'avortement, des hôpitaux comme Phu-San nécessitent des programmes de formation qui intègrent les conseils et les compétences cliniques, et abordent les facteurs culturels empêchant une interaction équitable du personnel de santé et des femmes. Il faut aussi établir un système de supervision qui soutienne les personnels de santé tout en s'assurant qu'ils mènent des séances d'information et de conseil de qualité.

Resumen

Seis meses después de la implementación de un proyecto de Atención Integral del Aborto en el Hospital Phu-San, maternidad principal de Hai Phong en Viet Nam septentrional, se realizó un estudio de los servicios de aborto, que exploró la interacción entre los prestadores de servicios y las usuarias, y la influencia de los valores culturales en la calidad de la atención. Se emplearon modalidades cuantitativas y cualitativas: una encuesta estructurada de tres partes entre 748 mujeres antes y después del aborto, 20 entrevistas con mujeres justo después del aborto, siete entrevistas con personal de salud y 100 observaciones de participantes. Tanto las mujeres como el personal equipararon la calidad de la atención con un mejor desempeño técnico del procedimiento de aborto. La falta de conocimientos y habilidades tuvo un impacto negativo en el suministro de información y consejería de calidad respecto al entendimiento y la aceptación de la anticoncepción, el tratamiento de infecciones ginecológiacas y la prevención de infecciones postaborto. Para mejorar la atención del aborto en hospitales como el Phu-San, se necesitan programas de capacitación que integren la consejería y habilidades clínicas y aborden los factores culturales que obstruyen la interacción entre el personal de salud y las mujeres de manera equitativa. Debe establecerse un sistema de supervisión con apoyo que le impute al personal de salud la responsabilidad de llevar a cabo sesiones de consejería e información de alta calidad.

Making abortion safe plays a significant role in the health and well-being of women, yet good quality abortion services are still unavailable to a large proportion of the world's population, especially those in developing countries.Citation1–3 In Viet Nam, abortion has been legal and available on request since 1960.Citation4 The abortion rate started to increase in the beginning of the 1980s, at first slowly and then by the late 1980s rapidly,Citation5 with a concomitant decline in the total fertility rate from 4.0 in 1987 to 1.9 in 2002.Citation6 In the mid-1990s, Viet Nam had one of the highest abortion rates in the world, 83 per 1,000 women of reproductive age.Citation7 The increased abortion rate was associated with a limited choice of modern contraceptive methods, a high IUD failure rate, a strict population policyCitation8 and often neglect of post-abortion contraceptive counselling and provision, which might have avoided some repeat abortions.Citation4 Unlike other countries with similar situations, abortion data have been recorded meticulously and even overstated in Viet Nam in order to obtain increased allocation of antibiotics.Citation8 Thus, the abortion rate in Viet Nam in the 1980s and 90s may not have been much higher than that in other countries with a similar rapid fertility decline. The fertility decline has now levelled off; in 2002, the abortion rate had decreased to 60 per 1,000 women aged 15–44.Citation6

The Government of Viet Nam recognises that quality of care is an important aspect of abortion services. The need for quality of care was officially recognised in the Reproductive Health Programme in 1994, following the recommendations of the International Conference on Population and Development. The National Strategy on Reproductive Health Care in 2000 also had the objective of ensuring access for all women to high quality reproductive health services by 2010. The strategy includes reducing unwanted pregnancy by 25% and improving quality such that 90% of women seeking abortion services receive information and counselling on reproductive health and contraception.Citation9 The first National Standards and Guidelines for Reproductive Health Care Services were developed in 2002 and stress that women have the right to information and respectful treatment within the public health system.Citation10

In addition, the Ministry of Health is partnering with Ipas to implement high quality, women-centred abortion care through the Comprehensive Abortion Care project, in four provincial hospitals to date.Footnote* The project adheres to the National Standards and Guidelines for Safe Abortion, which stress the importance of safe abortion techniques, counselling and infection prevention. One of the project's main priorities was to replace dilatation and curettage (D&C) with vacuum aspiration for first-trimester procedures by making manual vacuum aspiration (MVA) available and guaranteeing a steady supply of MVA kits. This has resulted in a significant technical improvement in quality of abortion care in Phụ-Sàn Hospital in Hài Phòng, northern Viet Nam.Citation11 To further study the quality of abortion care in Phụ-Sàn Hospital, we focused on provider–patient relations and provision of information and counselling, two often forgotten aspects of quality of care.

Study setting

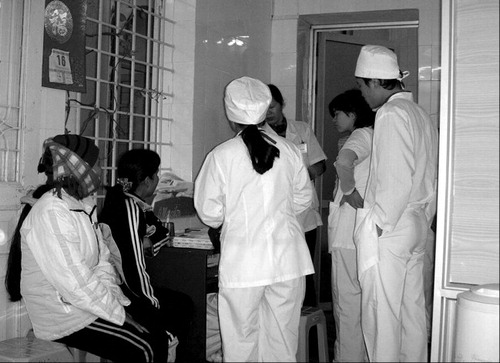

Phụ-Sàn Hospital provides maternity care, including abortion services, to nearly 500,000 women. It has two departments providing abortion and family planning services: the Department of Pay-for-Services (“Dịch vụ”) and the Department of Family Planning. This study was conducted in the Department of Family Planning, where the Comprehensive Abortion Care project was implemented in 2003. Staff working in the clinic include five medical doctors and nine midwives. Induced abortions are provided by the doctors; counselling is mostly done by a nurse who has received training from the project or rotates among both doctors and midwives.

A needs assessment prior to the implementation of the Comprehensive Abortion Care project found that the facility was poorly equipped and lacked space and privacy. Health staff, furthermore, did not provide women with post-abortion contraception counselling or information on infection prevention.Citation12 After the needs assessment, the project focused on MVA training for providers, improving counselling and infection prevention, monitoring of services and training and other aspects of comprehensive care.Citation11

As part of abortion care, the Family Planning Department was supposed to provide IUDs and injectable contraceptives post-abortion. If a woman wanted another method, she was referred to a nearby MCH/FP clinic. Condoms and vaginal foam had to be purchased at a drug store. During the study period, oral contraceptives and condoms were also made available to enable women to leave the hospital with their preferred method. Despite efforts being made, however, IUDs were not available at the beginning of our study.

Methods

A combined quantitative and qualitative approach was utilised. The study population comprised women seeking abortion services from 1 December 2003 through 30 April 2004. During this period 811 women sought abortion services in the hospital, 748 of whom underwent surgical abortions and were invited to take part in a three-part survey, using structured questionnaires. The first part took place after the women had had counselling and before the procedure; the second was after the procedure when the woman had recovered, and the third was two to three weeks after discharge when the woman returned for follow-up. The first part covered the women's socio-economic situation and reproductive history; all 748 women responded. The second part focused on quality of care, provider attitudes and quality of counselling, as well as post-abortion contraceptive intentions. Twenty-five of the 748 women did not participate in the second part, as they felt too weak or were in too much pain to respond. Of the 723 women who participated in the second part, 701 also did the third part, which focused on post-abortion contraception, symptoms of reproductive tract infection and treatment.

The data were entered twice, by two different operators, using the software programme Epi Data 3.0 from the Danish Society of Public Health, Denmark. The two data sets were compared and questionable entries reconciled. Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS 13.0) was used for statistical analysis.

Twenty of the 748 women who participated in the initial survey were selected for in-depth interview based on diversity in their demographic characteristics. They were assured that the interview would be conducted after they had had the abortion and would take place outside the hospital in an informal setting. These interviews focused on the women's satisfaction with the service, their opinion about the quality of information and counselling offered and of the health staff's competence in providing it. To ensure confidentiality, the time and place of the interviews were decided by the respondents. About half of the interviews were conducted in the respondents' homes. The others were in coffee shops or in the home of the first author. All the interviews were conducted and recorded by the first author and thereafter fully transcribed in Vietnamese. The coding of data was determined by the guideline; transcript segments were classified by the topic being discussed. Additionally, the first author had informal discussions with five doctors and two nurses during lunch times and after working hours to get providers' perspectives on quality of care.

Participant observations were carried out by the first author, using an approach inspired by Donabedian's and Bruce's frameworks for evaluating quality of care.Citation13Citation14 Observations covered a wide range of behavioural activities such as staff technical competence and interaction with women having abortions. One hundred participant observations were carried out during each stage of abortion: pre-procedure counselling, while preparing instruments and supplies, during the termination and recovery. The observations were filled in on a structured form and a scoring system was applied as to whether the activity was not observed at all, or part of the time or always.

All the women were informed about the study objectives as well as the voluntary nature of their participation. Confidentiality and anonymity were guaranteed and informed consent was obtained. The study was approved by the ethics committee at the University of Copenhagen.

Results

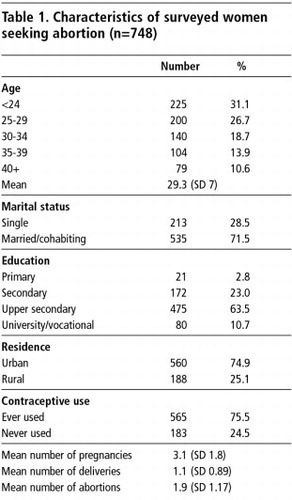

The mean age of the 748 women was 29 (range 17–51) (Table 1). Approximately one-third were single. The average number of children was 1.6. The mean number of pregnancies was 3.1 (range 1–11). The mean number of abortions was 1.9 (range 1–9) and of deliveries 1.1. Most abortions (93%) were performed in the first trimester of pregnancy.

Provider–patient interactions

In the survey, 92% of the women said that they were treated respectfully by health staff (Table 2). In the in-depth interviews, in contrast, we were told that interaction with providers was poor; the women often felt they were treated impolitely. They did not express their dissatisfaction, however, but silently accepted staff attitudes as they feared that complaints might affect the quality of care. One woman's reaction when her doctor left the room to have a chat with her colleagues was:

“I am fretting from having to wait too long but I just didn't dare to ask her at that moment because I was afraid that she would blame me for disturbing her. I thought it was better to wait until she came back.” (In-depth 12)

Health care culture in Viet Nam places the patient in a subordinate position to the provider. Thus, providers allowed their work to be interrupted by private matters that they thought were more important than women's needs, even when preparing for a pelvic examination or during counselling.

“… I sometimes disappear for a quarter or half an hour. Indeed, I have nothing to do, but that is the way we [health staff] let them know who is superior here. Moreover, our friendships are more important than the patients.” (Dr T, informal conversation)

However, the women themselves did not expect better than this. Their expressions of respect for the staff seemed mainly to reflect their satisfaction with providers' technical skills. For them, technical skills and the absence of complications were more important. They tended to ignore what has been termed cultural competence, i.e. the combination of knowledge, clinical skills and behaviour that lead to positive outcomes in patient care.Citation15 Their main priority was to get a safe, quick pregnancy termination and they paid less attention to other aspects of care. Health staff likewise tended to regard quality of care mainly as a matter of technical competence. Even when prompted, only one doctor acknowledged interpersonal relations as an element of quality of care.

The participant observations support these findings. The majority of women were greeted in an indifferent manner. There were no signs on the walls directing women to where they needed to go. The women were often pushed around in the corridors and scolded by staff, who would accuse them of causing the chaos and disorder in the department.

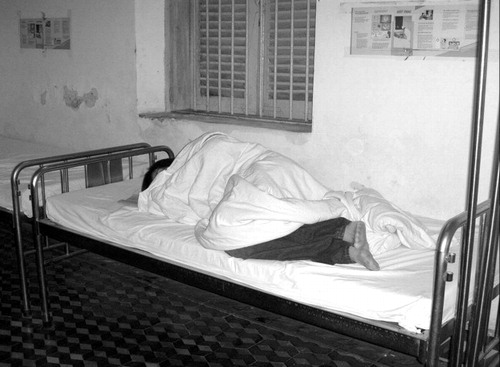

Box 1 shows the quality of care indicators measured and how frequently they were observed. One-third of the women did not receive any information or support during the abortion procedure, while the rest only received partial information (data not shown). Only 5% of the women received any assistance from staff in getting to the recovery room; most had to depend on the help of relatives. Nor did the staff often express empathy towards the women. Furthermore, none of the staff were present in the recovery room during any of the observations, and none of the women had their condition checked before they were discharged.

Privacy and dignity

Poor interpersonal relations may partly be explained by space constraints in the clinic. There was hardly any space to allow for privacy during pelvic examinations or counselling. In addition, women were ambivalent about having to be naked in front of others. They acknowledged that this was “normal” because “this is an abortion clinic, not a general health clinic, therefore everyone has to do the same”. But at the same time, many found it embarrassing:

“Isn't it shameful! You see, we are human beings and women, not things that they can throw on the ground like paddy to be dried in the sun (phoi lúa). But what should I do? You cannot express your shame publicly; otherwise you will be teased by the health staff or other women for trying to save your face (giu si dien). After all, everyone has to do the same. The only thing I could do was pretend everything was OK.” (In-depth 5)

Information and counselling on post-abortion contraception

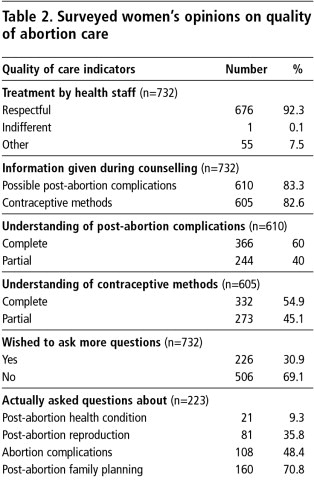

The quantitative data show that most of the women, as part of the pre-procedure counselling, received information about abortion complications and contraceptive methods. However, although the majority said they received information about the range of methods, only half said they had understood the information completely and one-third had wanted to know more about abortion-related issues (Table 2).

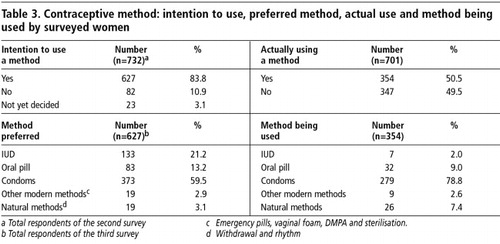

After the initial interview, 84% said they intended to use contraception but only half of them were actually using a method at the follow-up visit. Furthermore, there was a discrepancy between the method they said they intended to use and the method they were actually using (Table 3). For instance, many more women wanted an IUD than had actually been fitted with one, whereas more were actually using condoms than had said they wanted to.

Although the women thought information on post-abortion contraception was important, many said they were not offered an opportunity to ask questions or express concerns and thereby make an informed choice. Thus, they were of the opinion that it did not matter whether they were counselled or not, and so they did not pay much attention during the session. While craving for more information about gynaecological problems, they also felt reluctant to ask questions:

“…I would like it if the doctor or counsellor had told me more about “my disease” but they did not. I once asked a question but the way she answered made me lose my enthusiasm. I would rather visit a private doctor where I can ask.” (In-depth 16)

Most of the women wanted contraceptive information that addressed their specific life situation and previous contraceptive experience. Instead, identical information was given to everyone. Thus, counselling was perceived as tedious.

“Nothing is new. I can also name these family planning methods because I have heard about them from the family planning motivator in my commune. I don't know how they work and what side effects they have, and the counsellor here did not tell me.” (In-depth 4)

“It was a boring presentation. You see, the nurse was just doing her duty… what she said was about family planning but very vague. I don't remember what I was told.” (In-depth 2)

Health staff also complained about the contraceptive counselling sessions. They felt they had insufficient counselling skills, inadequate materials, time constraints and lack of supervisory support. They also felt there was a lack of interest on the women's part. They did not consider counselling as part of abortion care but as an extra activity which they did not want to perform, even though they acknowledged the importance of contraceptive use. Many did not like the counselling being rotated among them, and many of the nurses said they would prefer not to do contraceptive counselling.

“…the only available information on abortion and family planning I can use for counselling are these reading materials from a training course that I attended a few months ago… I am not sure if I could answer all the women's questions… And I am fed up with those who just sit there and listen to me without paying any attention, and they are many… I just try to get through it as quickly as possible.” (P, a counsellor)

The observations painted a similar picture. Though the women were routinely offered the opportunity to express their concerns, very few used the opportunity and many were observed to accept a method quickly. This may explain the difference between their intended and actual method choice. Moreover, many who had asked for an IUD left the clinic without having had one inserted, because neither the counsellor nor the woman had mentioned it to the doctor who did IUD insertions.

Post-abortion infection prevention

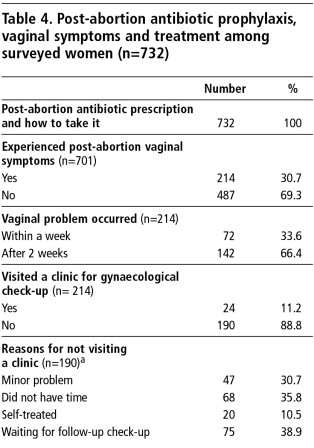

The quantitative study revealed that all respondents had been prescribed prophylactic antibiotics and advised how to take the medicine (Table 4). At the follow-up interview, one-third said they had experienced post-abortion symptoms such as vaginal irritation or discharge, but only 11% had sought professional care. Among those with symptoms, about one-third considered them minor and not needing attention, while 10% had self-treated using over-the-counter medicine. Problems finding the money to buy the prescribed antibiotics sometimes made women very creative:

“I bought the antibiotics as prescribed. The first day I took the medicine as instructed while listening to (xem xét) my body's reaction. If the (vaginal) discharge seemed normal, I stopped and saved the rest for my children in case they get ill.” (In-depth 16)

Health staff realised that lack of management of reproductive tract infections (RTIs), which they considered very common among Vietnamese women, was a major weakness in the clinic. Yet they did not use the counselling session to inform women about RTIs or post-abortion infection. Furthermore, many of the staff found it inappropriate to test the women for RTIs, as they believed that nearly all the women had RTIs and that the broad-spectrum antibiotics all women were prescribed would prevent any infection.

“It's ridiculous to ask these women to have RTI tests because almost 99%, if not all 100%, of those who seek abortion already have an RTI.” (Doctor, informal conversation)

“…Abortion patients are prescribed antibiotics for secondary infection prevention that are anti-bacterial and imidazole derivatives. Both pre- and post-abortion infections are cured properly with these.” (Microbiologist, informal conversation)

Participant observations supported these comments. Counselling about these issues was minimal. Information about RTI symptoms identified during pelvic examination was recorded in the woman's file but rarely shared or discussed with the woman, nor prevention information given. Wall-charts and leaflets did provide some information about RTIs, but the material was not always made available and in some cases was outdated. For example, one leaflet described vaginal douching as an acceptable preventative strategy. The risk of abortion-related infection was mentioned on the printed informed consent form which women must read and sign, but the form was written in professional language, not for the woman. No information was given about what to do if symptoms occurred.

Discussion

Six months after successful improvements by the Comprehensive Abortion Care project in many aspects of abortion care in the hospital, poor quality of care was still found with regard to provider–patient relations, information provision and contraceptive counselling. We believe these problems are rooted mainly in medical culture and social beliefs, values and habits and in women's feelings of resignation as patients to their subservient role in health care culture and their lack of awareness of their rights as patients, even the right to ask questions.

The women's answers on sensitive issues on the structured questionnaire may have been affected by “courtesy bias”,Citation16 i.e. they said what they thought

was socially acceptable. Or, culturally, the women may have had such low expectations that whatever level of care they received, it would have met or even exceeded their expectations.Citation17–20 Thus, they expressed general satisfaction with the services offered in spite of dissatisfaction with lack of privacy, feeling unable to ask questions or get the information or contraceptive method they wanted.In many reproductive health care settings, the socio-cultural atmosphere often receives less consideration than clinical skills.Citation18 Furthermore, Vietnamese culture is still influenced by the principles of Confucianism in which harmony, duty, honour, respect, education and allegiance to the family and society are considered core values. The influence of Confucianism combined with the values of socialism has resulted in a devaluation of autonomous decision-making, which has partly contributed to what is called “cultural resignation” (cam chiu) in relation to everyday life.Citation21 Together with the current provider-centred practice in the public health system in Viet Nam,Citation22 this greatly affects women's experiences of health care,Citation23 as they find themselves being treated as subordinates who cannot question anything. Thus, their silence is perceived as a sign of virtuous behaviour and fulfilment of their social duty.

In the years 1954–86, before the economic reforms (Ði moi), health care providers were the Government's representatives in the public health system with responsibility for taking good care of the people. The public health system has greatly improved as a result, and Viet Nam has made impressive health gains in recent decades.Citation24 However, subsidisation of public health care and the restriction of private services for more than 30 years have given public health staff great authority and privileges, which have tended to persist. A Vietnamese saying is that “to cross the river you have to depend on the boatman” (qua sông thi phài luy ò). In the figurative sense, those who seek care from public health services have to gain the favour of health staff and are dependent on their good will. This does not encourage a culture of patients' rights but one of “asking and giving permission” (co chê xin–cho) that has gradually become part of Vietnamese everyday culture. It is widely applied in every government service sector – education, culture, economy and health. To further improve abortion care in this context, the question that arises is how the boatman can become caring and supportive.

Improvements in the quality of contraceptive services in abortion clinics in other settings have been shown to increase post-abortion contraceptive uptake greatly.Citation25–27 In spite of low contraceptive uptake and lack of information about contraception, RTIs and post-abortion infection, information and counselling were not considered a priority by women or providers in this hospital. Lack of training and resources to provide good quality counselling were in contrast to providers' technical skills in doing abortions, where a high level of competence was found.Citation11

Because prophylactic antibiotics were given to all the women undergoing abortion, irrespective of presence of infection, health staff were not concerned about whether the women had RTI symptoms or post-abortion infection. Nor did they stress the importance of taking the full antibiotic dosage or check whether women had done so, when in fact, they sometimes had not.

To further improve abortion care in public health facilities such as Phụ-Sàn Hospital in Hài Phòng, provision of information at community level on reproductive health and rights would help to empower women to ask questions and overcome “cultural resignation”. Training programmes for abortion service providers and medical students are needed that integrate communication, counselling and clinical skills and address the cultural factors that hinder health staff and women from interacting in an equitable manner. In addition, information and resources and the availability of the full range of contraceptive methods are needed so that providers can deliver post-abortion contraception that meets women's needs. Last but not least, a supportive supervisory system, which ensures that trained health staff conduct high quality information and counselling sessions, should be established.

Acknowledgments

We would like to express our gratitude to Dr Ðoàn Bích Ngoc, Director, and Dr Ð Thi Thu Thuy, Vice Director, of Hài Phòng Phụ-Sàn Hospital for their assistance in facilitating this work. We also thank Dr Nguyên Thi Lan, Dr °ào Thi Liên and staff of the departments of Family Planning and Microbiology, where this study took place. We thank Dr Tran Thu Thuy, Hài Phòng Committee for Population, Family and Children for her important contributions. Thanks also to the women who were willing to share their experiences and time with us.

Notes

* This project in Hanoi, Ho Chi Minh City, Ðông Nai and Hài Phòng provinces, documents the strategies and challenges of scaling up abortion care activities and the impact on quality, cost and effectiveness. Physicians and other providers were trained in the use of MVA; help was given to establish guidelines on record-keeping and standard practices such as infection prevention; and medical abortion and safer second-trimester abortion methods were introduced at tertiary, provincial, district and commune levels of the health system. In 2001, the project was implemented in the two biggest institutions, Institute for the Protection of Mother and Newborn and Tù-DłOb-Gyn Hospital, and in 2003 in Hài Phòng and Ðng Nai Ob-Gyn hospitals.Citation11

References

- D Huntington. Meeting women's health care needs after abortion. Program Briefs 1. 2000; Population Council/Frontiers: Washington DC.

- J Benson, R Gringle, J Winkler. Preventing unwanted pregnancy: management strategies to improve post-abortion care. Advances in Abortion Care. 5(1): 1996; 1–8.

- T Mclnerney, TL Baird, AG Hyman. A guide to providing abortion care. Technical Resources for Abortion Care. 2001; Ipas: Chapel Hill NC.

- World Health Organization. Abortion in Viet Nam: an assessment of policy, programme and research issues. Expanding options in reproductive health. WHO/RHR/HRP/ITT/99.2. 1999; WHO: Geneva.

- Johansson A. Dreams and dilemmas: women and family planning in rural Viet Nam. PhD thesis, Karolinska Institutet. Stockholm, Sweden, 1998.

- Viet Nam National Committee for Population Family and Children. Viet Nam Demographic and Health Survey 2002. 2003; VCPFC: Hanoi.

- SK Henshaw, S Singh, T Haas. Recent trends in abortion rates worldwide. International Family Planning Perspectives. 25(1): 1999; 44–48.

- Nghia DT, KhêND. Viet Nam abortion situation. Country report. International conference on Expanding Access: Mid-level Providers in Menstrual Regulation and Elective Abortion Care. Kwa Maritane Lodge, 3–6 December 2001.

- Viet Nam Ministry of Health. National Strategy on Reproductive Health Care for the Period 2001–2010. 2003; VMOH: Hanoi.

- Viet Nam Ministry of Health. National Standards and Guidelines for Reproductive Health Care Services. 2003; VMOH: Hanoi.

- Ipas. Ipas in Viet Nam: a country report. 2005. At: <www.ipas.org/english/research/current_research.asp#Asia. >. Accessed 9 September 2006.

- Ipas. Needs assessment of abortion care. 2003; Ipas Viet Nam: Hanoi.

- A Donabedian. Selecting Approaches to Assessing Performance. 2003; Oxford University Press: Oxford.

- J Bruce. Fundamental elements of the quality of care: a simple framework. Studies in Family Planning. 21(2): 1990; 61–91.

- GG Hall. Culturally competent patient care. A guide for providers and their staff. 2001. At: <www.myapipa.com/provcc.htm. >. Accessed 9 September 2006.

- RE Ruth, JT Bertrand. Monitoring quality of care in family planning programs: a comparison of observations and client exit interviews. International Family Planning Perspectives. 27(2): 2001; 63–70. At: <www.guttmacher.org/pubs/journals/2706301.html>. Accessed 1 August 2006.

- T Williams, J Schutt-Ainé, Y Cucca. Measuring family planning service quality through client satisfaction exit interviews. International Family Planning Perspectives. 26(2): 2000; 63–71.

- B Wilde, M Larsson, G Larsson. Patients' views on quality of care: a comparison of men and women. Journal of Nursing Management. 7(3): 1999; 133–139.

- NM Thang, R Johnson, E Landry. Quality of contraceptive and abortion services at three sites in Viet Nam. 1998; Statistical Publishing House: Hanoi.

- VQ Nhân, LTP Mai, NT Hau. A situation analysis of public sector reproductive health services in seven provinces of Viet Nam. 2000; Population Council Viet Nam: Hanoi, 90.

- JC Schafer. Cultural background: religion, language, myths, legends. JC Schafer. Vietnamese Perspectives on the War in Viet Nam. 1997; Yale University Council on Southeast Asia Studies: New Haven. At: <www.yale.edu/seas/bibliography/chapters/chap6.html>. Accessed 26 August 2006.

- DV Ða t, CW Binns, AH Lee. Measuring client-perceived quality of maternity services in rural Viet Nam. International Journal for Quality in Health Care. 16(6): 2004; 447–452.

- M Whittaker. Rights and realities: Vietnamese women speak. 1997; Medical Women's International Association: Sydney.

- M Segall, G Tipping, H Lucas. Economic transition should come with a health warning: the case of Viet Nam. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health. 56(7): 2002; 497–505.

- J Tabbutt-Henry, K Graff. Client provider communication in post-abortion care. International Family Planning Perspectives. 29(3): 2003; 126–129.

- J Solo, DL Billings, C Aloo-Obunga. Creating linkages between incomplete abortion treatment and family planning services in Kenya. Studies in Family Planning. 30(1): 1999; 17–27.

- V Rasch, S Massawe, Y McHomvu. A longitudinal study on different models of post-abortion care in Tanzania. Acta Obstetetricia et Gynecologica Scandinavica. 83(6): 2004; 570–575.