Recent randomised clinical trials on the efficacy of male circumcision show that medically performed adult male circumcision can be safe and efficacious in reducing the sexual transmission of HIV from HIV-infected women to their HIV-uninfected male partners.Citation1–3 In addition, a stochastic simulation model of the impact of male circumcision on HIV incidence and cost per infection averted, using empirically derived parameters from a cohort in Rakai, Uganda, suggests that male circumcision could have substantial impact on the HIV epidemic and provide a cost-effective prevention strategy, if benefits are not countered by behavioural disinhibition.Citation4 A recent WHO/UNAIDS technical consultation recommended that male circumcision be recognised as an efficacious intervention for HIV prevention in men especially in countries with hyper-endemic and generalised epidemics with a low prevalence of male circumcision.Citation5

It is important to note that male circumcision does not provide complete protection against HIV acquisition. Circumcised men can still become infected with the virus and, if HIV infected, they can infect their sexual partners. It is therefore important that men opting for the procedure and their partners be provided with careful and balanced information and education materials that stress the partial protection offered by male circumcision and emphasising that male circumcision is not a “magic bullet” for HIV prevention but is complementary to other means of reducing the risk of HIV infection such as abstinence, fidelity, use of condoms and voluntary counselling and testing (VCT).Citation5

If circumcised men believe that they are protected from HIV, there is a possibility that they will compensate for their perceived risk reduction by engaging in higher risk behaviours, thereby mitigating any benefit of circumcision in preventing HIV infection.Citation1Citation2 Some observational studies have shown that circumcised men engage in higher risk behaviours than uncircumcised men,Citation6 and the Orange Farm trial in South Africa found circumcised men to have slightly higher levels of risk compared to uncircumcised men.Citation3 However, results from the other two randomised trials of male circumcision in Kisumu, Kenya and Rakai, Uganda, did not find any evidence of risk compensation in circumcised relative to uncircumcised men. This could have been due to intensive health education and access to risk-reduction HIV counselling and testing provided during the trials to minimise behaviour disinhibition.Citation1–3 These findings are consistent with a cohort study conducted in Siaya and Bondo districts in Kenya which found that circumcised men did not engage in more risky sexual behaviours than uncircumcised men.Citation7

In this article, we describe voluntary HIV counselling and testing (VCT), sexually transmitted infection (STI) management and safer sex promotion activities conducted as part of the male circumcision trial in rural Rakai district, south-western Uganda. Methods and results are described together following a short description of the overall study.

Study description

The Rakai trial of male circumcision for HIV prevention in men, funded by the US National Institutes of Health, has been described previously.Citation1 In brief, 4,996 HIV negative, uncircumcised men aged 15–49 years who agreed to receive their HIV test results through voluntary counselling and HIV testing provided by the study, and who consented to be randomly assigned to receive immediate circumcision (intervention group, n=2,474), or to have circumcision delayed for 24 months (control group, n=2,522) were enrolled into the study. Screening and enrolment were done in a central study facility and in mobile facilities in the rural communities. Before screening, participants were informed of study procedures and risks through verbal presentations, written materials and an information video. After providing written, informed consent for screening, a venous blood sample was obtained for HIV testing and participants were given a physical examination. Men who were HIV-positive or declined to receive their HIV results were enrolled in a complementary trial which will be reported separately. Eligible participants were asked to provide an additional written, informed consent for enrolment. The consent forms described the risks and benefits of participation, randomisation and other trial procedures, and provided information on HIV prevention (sexual abstinence, monogamous relationships with an uninfected partner and consistent condom use).

At enrolment, participants completed a detailed questionnaire administered by a trained interviewer on socio-demographic characteristics, sexual risk behaviours, genital hygiene and health. All participants in both groups were followed up at 4–6 weeks, and at 6, 12, and 24 months post-enrolment. At each follow-up visit, participants answered questions on sexual risk behaviours. These were about marital and non-marital partners, condom use, alcohol consumption with sexual intercourse, transactional sexual intercourse (in exchange for money or gifts) and symptoms of sexually transmitted infections (genital ulcer disease, urethral discharge or dysuria) since their previous visit. Samples of venous blood and urine were collected, repeat HIV counselling and testing and health education were provided. Free condoms were offered to all sexually active participants at all study visits, and were also available through community-based condom depots stocked by the Rakai programme. The male circumcision protocol was reviewed and approved by human subjects institutional review boards in Uganda and the United States.

Qualitative assessment of male circumcision in the community

Qualitative studies of cultural practices, beliefs and attitudes about male circumcision were conducted prior to the trial and with men who were enrolled into both arms of the trial as well as with their partners, via focus group discussions and in-depth interviews of key informants. The objective was to gain an in-depth understanding of issues such as whether religious identity was affected by circumcision, cultural/traditional practices such as sexual cleansing (i.e. intercourse with a non-marital partner), enhancement of wound healing by early resumption of sex, rites of passage and other ceremonies, as well as the community's perception of the behaviours of circumcised men before and after male circumcision.

A preliminary analysis of 40 out of the 51 key informant interviews indicated that both men and women did not report any change in sexual behaviours following their (or their partner's) enrolment into the trial nor did they report engaging in any cultural and traditional practices or hold beliefs that might contribute to increased acquisition or transmission of HIV. One 29-year-old man in the intervention arm reported having heard of some men who had had their first sexual contact (following surgery) with women other than their steady partners because “they (the men) were saying that when you start… by having sex with [your] wife, you will have left a curse in her”. Qualitative data collection did not reveal such practices among men participating in the trial in Rakai. However, because such beliefs might translate into actual behaviour if not addressed, these findings were addressed within the Rakai Programme's ongoing risk-reduction counselling and health education sessions.

Voluntary HIV counselling and testing

Details about the Rakai Health Sciences Programme's VCT programme have been described elsewhere.Citation8 In brief, the Rakai Programme operates a network of 18 community-based counselling offices, each staffed with a community resident counsellor. All VCT counsellors have received training in HIV/AIDS counselling, and prior to the initiation of the male circumcision trial, they received intensive training in risk-reduction counselling, couple counselling promotion, good clinical practices and other study-related procedures.

At screening, all individuals were offered pre-test counselling and asked whether or not they wanted to receive their HIV test results. Men were free to accept or decline their HIV results, and this did not affect their access to all services provided to the community by the Rakai Programme.

A total of 5484 HIV-negative men were screened to participate into the NIH-funded male circumcision trial of whom 5,218 (95.1%) accepted VCT while 266 (4.9%) did not choose to learn their HIV results. Only those who accepted VCT and qualified on other inclusion criteria were eligible for enrolment into this study. HIV-negative individuals who declined their HIV test results as well as men who were HIV-positive at screening were enrolled into a parallel study funded by the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation.

Initially, a total of 5,000 eligible HIV-negative men were enrolled into the trial. However, during follow-up we discovered that four men (two in each study group) had re-enrolled under assumed names. For these individuals, the first enrolment record was retained in the dataset for the primary intent-to-treat analysis and the second enrolment was deleted, leaving 4,996 enrolled participants.Citation1

At subsequent visits, all participants received intensive HIV prevention counselling and were told that they could receive additional counselling and HIV test results from the Rakai Programme's community-based counselling offices. However, they were also informed that if their HIV status had changed (i.e. they had seroconverted), the Programme would contact them and provide VCT in their homes or in venues of their choosing. During follow up, 7.9% of persistently HIV-negative men in the intervention arm and 7.3% in the control arm requested repeat VCT. Thus, only a small proportion of HIV-negative participants who wanted to confirm their HIV-negative status were motivated to receive repeat VCT during follow-up, probably because we had assured them that they would be contacted if their HIV status had changed.

All individuals who seroconverted during follow-up were contacted and provided with post-test counselling and support, and were strongly encouraged to practise safer sex to avoid transmitting HIV to their sexual partners. All individuals who seroconverted during follow-up were referred to HIV treatment and care services provided by the Rakai Health Sciences Programme.

All spouses of the men who were enrolled in the trial were contacted and asked to participate in a parallel study funded by the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, which assessed whether male circumcision was acceptable to women and whether it may reduce the transmission of HIV and other sexually transmitted infections from men to their partners. All enrolled spouses were free to come with their partners for VCT or other services, including treatment of sexually transmitted infections.

Couple counselling was strongly encouraged among those with steady partners, and where couple counselling was declined or not possible, men were encouraged to share their HIV test results with their partners. No involuntary disclosure of HIV serostatus took place in line with Uganda's national policy on HIV counselling and testing.Citation9

STI management

At enrolment and at each follow-up visit, individuals were asked to provide blood and urine samples for testing for HIV and other STIs. Individuals who were HIV infected were referred to the Rakai Health Sciences Programme's antiretroviral treatment programme currently funded by the Presidential Emergency Fund for AIDS Relief.Citation1 Individuals with STI symptoms were treated syndromically because STI testing could not be done in real time, with the exception of syphilis serology. All syphilis-seropositive participants were treated with intra-muscular benzathine penicillin injection or with azithromycin if they refused the injection or were allergic to penicillin. All men who were treated for syphilis were given a contact sheet to notify their partners to come for treatment as well. Partners were free to receive treatment at the community-based circumcision study mobile facilities or at the penicillin bases established at existing government health units within their community. Penicillin was also provided to pregnant women with positive serology.

The number of participants who tested positive for syphilis at baseline and at each follow-up visit were similar in both study arms. Over the 24 months, there were 218 men with positive syphilis serology in the intervention arm and 207 in the control arm. Overall, 93% of syphilis cases which needed treatment in the intervention arm (175/218) and 95% of those in the control arm (168/207) received treatment. Over 90% of those treated for syphilis received intra-muscular benzathine penicillin injection at first or subsequent contacts.

The proportions of female partners with serologic syphilis who were treated over the 24 months was 79.7% of female contacts of syphilis-positive men enrolled in the intervention arm and 75.2% of female contacts of syphilis positive men enrolled in the control arm. The main reason for female contacts not receiving treatment was failure of those contacts to come for treatment or active refusal of treatment.

Men were examined for genital ulcer disease (GUD) at screening and at each follow-up visit. Men who had GUD at screening received treatment before they were enrolled. GUD identified through penile examination at subsequent follow-ups was treated syndromically and clinically monitored to ensure complete resolution. All men with GUD or syphilis were strongly encouraged to abstain from sex or use condoms until complete healing was achieved.

As noted in the trial, male circumcision reduced the rates of symptomatic GUD.Citation1 Over 24 months, there were 34 cases of clinically diagnosed GUD in the intervention arm, all of whom were treated and 27 (79.4%) certified as cured. In the control arm, there were 79 cases of GUD diagnosed, all of whom were treated and 63 (79.7%) certified as cured. The cases without certification of cure (eight in the intervention arm and 16 in the control arm) were men who failed to return for post-treatment follow up. Since symptomatic GUD is associated with higher rates of HIV acquisition,Citation1 achievement of high GUD treatment and cure rates could reduce the risk of HIV acquisition in circumcised and uncircumcised men in Rakai.

Safe sex promotion and practice

At enrolment and at each subsequent follow-up visit, men were provided with intensive health education and encouraged to adopt safe sex behaviours. Participants in both arms received identical information on sexual abstinence, monogamy with HIV-uninfected partners, correct and consistent condom use, genital hygiene, avoidance of behavioural disinhibition following circumcision, and STI/HIV prevention. This was in line with Uganda's ABC strategy for HIV/STI prevention. Additional safer sex counselling was provided during pre-test counselling at each visit and whenever the participant came in contact with a Programme clinician. Women in the complementary Gates-funded study also received these HIV prevention messages and services.

Men who were enrolled into the intervention arm and who received circumcision were strongly cautioned against early resumption of sex before complete and certified wound healing was attained, 4–6 weeks post-surgery. There were concerns that some circumcised men who resumed sexual activity before wound healing might be at increased risk of HIV infection and surgical complications.Citation5 These and other potential harmful beliefs or perceptions identified through qualitative research were addressed in one-to-one sessions with the Programme counsellors and clinical officers at each follow-up visit for both trial arms and at community-wide mobilisation and health education meetings.

At community level, health educators emphasised the importance of refraining from sex until complete wound healing after circumcision and stressed the risk of HIV acquisition that could be associated with resumption of sex before healing. Uncircumcised men were strongly encouraged to abstain from sex, remain faithful to their sexual partners and use condoms consistently in other circumstances. At an individual level, Programme clinicians provided post-operative instructions to all circumcised men and provided written and verbal instructions to their partners, emphasising care of the wound and strongly encouraged them to abstain from sex until wound healing was certified as complete. Similar information on safer sex, emphasising sexual abstinence, consistent condom use or faithfulness to the sexual partner was provided to men enrolled in the control arm during follow-up.

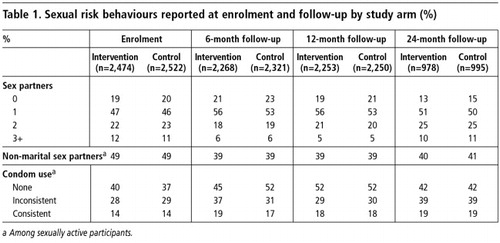

Table 1 shows sexual risk behaviours at enrolment and during follow-up by study arm. The proportion of participants reporting no sexual partners was similar in both arms, and declined over time in both arms partly due to age-associated initiation of sex among younger participants. However, persons reporting three or more partners decreased during the first year follow-up in both arms, and returned to baseline levels in the second year. The proportion of men reporting non-marital relationships declined after enrolment and remained similar in both study arms. Consistent condom use increased during follow-up in both arms and remained higher than enrolment throughout the study. The proportion reporting inconsistent condom use fluctuated, but was similar in both arms, except during the first follow-up interval when inconsistent use by the circumcised men exceeded that of the controls. Thus, it would appear that safer sex education had a similar effect in both study arms, and showed a reduction in 3+ partners and non-marital sex and greater consistent condom use.

With respect to sexual abstinence following surgery, 82.9% of circumcised men reported that they did not initiate sexual relations until wound healing was certified.

Discussion

The trial showed a 51–60% efficacy for prevention of incident HIV in circumcised men compared to uncircumcised men.Citation1 While there is now compelling evidence regarding the efficacy of male circumcision in reducing the risk of HIV acquisition in circumcised men, programme implementers should not consider male circumcision as a stand-alone intervention but as part of a comprehensive HIV prevention package including HIV counselling and testing, diagnosis and treatment of STIs, sexual abstinence, monogamy with an uninfected partner, condom promotion, behavioural change counselling and other methods as they are proven effective.Citation2

All participants received identical risk reduction health education on safer sex, genital hygiene, circumcision disinhibition and STI/HIV prevention at enrolment and at each follow-up visit. The increase in consistent condom use from 14% at enrolment to 19% at 24 months of follow-up and the declines in the proportion of men reporting non-marital partners in both arms suggest that risk-reduction counselling coupled with intensive health education could offset potential risk compensation following male circumcision.Citation1Citation2 Also, the finding that up to 83% of men reported that they did not resume sex before certified wound healing is encouraging and suggests that many men adhered to post-operative instructions. However, the fact that up to 17% of circumcised men resumed sex before certified wound healing is disturbing, given that this might elevate the risk of HIV infection in men and their partners, as well as increase the risk of post-operative wound complications.

Future circumcision programmes will need to stress that male circumcision does not protect men or their partners 100% of the time, and that early resumption of sexual relations before complete wound healing may increase the risk of acquisition of HIV infection among recently circumcised HIV negative men as well as the risk of HIV transmission to female partners of recently circumcised HIV positive men, and may also increase the risk of post-operative complications in both HIV-positive and HIV-negative men.Citation5

If circumcision of HIV-negative men is promoted on a wide scale, especially in high HIV prevalence settings, as in sub-Saharan Africa, where the main mode of HIV transmission is largely heterosexual, male circumcision could potentially reduce the burden of HIV in uninfected women.Citation10 A Tanzanian study suggests that men are approximately four times more likely than women to bring HIV into a stable partnership.Citation11 With fewer men becoming infected with HIV, secondary transmissions to female partners is likely to be substantially reduced. Thus, interventions such as male circumcision (and the practice of safer sex) that reduce the proportion of male partners acquiring HIV will potentially result in reduced numbers of women acquiring HIV from infected partners.

In conclusion, our findings suggest high and similar uptake of VCT, STI management and safer sex behaviour, which could potentially explain why we did not observe any consistent or substantial evidence of behavioural disinhibition after circumcision in the study population. Because male circumcision does not offer full protection against HIV acquisition or transmission, future male circumcision programmes will be most effective if they are implemented in conjunction with intensive risk reduction promotion and messages that address the risk associated with resumption of sex before wound healing in circumcised men.

Acknowledgements

The Rakai male circumcision trial was supported by a grant (UO1 AI11171-01-02) from the National Institutes of Allergy and Infectious Disease (NIAID), Division of AIDS, National Institutes of Health (NIH), and in part by the Division of Intramural Research, NIAID, NIH. We thank the members of the NIH data safety monitoring board who monitored this trial, as well as the institutional review boards that provided oversight (the scientific and ethics committee of the Uganda Virus Research Institute, the committee for human research at Johns Hopkins, and Western Institutional Review Board). We are also grateful for the advice provided by the Rakai community advisory board. Finally, we wish to express our gratitude to study participants whose commitment and cooperation made the study possible.

References

- RH Gray, G Kigozi, D Serwadda. Male circumcision for HIV prevention in men in Rakai, Uganda: a randomised trial. Lancet. 369: 2007; 657–666.

- RC Bailey, S Moses, CB Parker. Male circumcision for HIV prevention in young men in Kisumu, Kenya: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 369: 2007; 643–656.

- B Auvert, D Taljaard, E Lagarde. Randomized, controlled intervention trial of male circumcision for reduction of HIV infection risk: The ANRS 1265 trial. PLoS Medicine. 2(11): 2005; e298.

- RH Gray, X Li, G Kigozi, D Serwadda. The impact of male circumcision on HIV incidence and cost per infection prevented. A stochastic simulation model from Rakai, Uganda. AIDS. 21: 2007; 845–850.

- WHO/UNAIDS. Male circumcision and HIV prevention: research implications for policy and programming. WHO/UNAIDS Technical Consultation: Montreux, 2007. At: <www.who.int/hiv/mediacentre/news68/en/index.html. >. Accessed 5 April 2007.

- RC Bailey, S Neema, R Othieno. Sexual behaviors and other HIV risk factors in circumcised and uncircumcised men in Uganda. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes. 22(3): 1999; 294301.

- KE Agot, JN Kiarie, HQ Nguyen. Male circumcision in Siaya and Bondo districts, Kenya: prospective cohort study to assess behavioral disinhibition following circumcision. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes. 44: 2007; 66–70.

- JK Matovu, G Kigozi, F Nalugoda. The Rakai Project counselling programme experience. Tropical Medicine & International Health. 7(12): 2002; 1064–1067.

- Uganda Ministry of Health. Uganda National Policy on HIV Counselling and Testing. Kampala: Ministry of Health, 2005. At: <www.aidsuganda.org/sero/HCT%20policy.pdf. >. Accessed 5 April 2007.

- BG Williams, JO Lloyd-Smith, E Gouws. The potential impact of male circumcision on HIV in sub-Saharan Africa. PLos Medicine. 3(7): 2006; e262.

- S Hugonnet, F Mosha, J Todd. Incidence of HIV infection in stable partnerships: a retrospective cohort study of 1802 couples in Mwanza region, Tanzania. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes. 30: 2002; 73–80.