Abstract

Rural women with obstetric complications access many health providers in Koppal, the poorest district in the state of Karnataka, south India. Yet they die. Based on insights derived from case studies of women seeking emergency obstetric care and participant-observation of government health services, this article highlights service delivery constraints that underlie the persistence of high levels of maternal mortality in Koppal. Weak information systems, discontinuity in care, unsupported health workers, haphazard referral systems and distorted accountability mechanisms are identified as critical service delivery problems. For example, maternal deaths are under-reported and not reviewed, antenatal care and institutional delivery are not linked to post-partum or emergency obstetric care, and health workers use inappropriate injections but don’t treat anaemia or sepsis. Families waste valuable time and resources accessing many providers but fail to get effective care, and blame is laid on lower-level health workers and women for not accessing institutional delivery. Lastly, the role of administrators and politicians in ensuring functioning health services is obscured. While important supply and demand-side reforms are being implemented, these do not constructively engage with informal providers nor address systemic service delivery constraints. Critical managerial change is required, without which new budgetary allocations will be squandered with little impact on saving women’s lives.

Résumé

À Koppal, le district le plus pauvre de l’État de Karnataka en Inde méridionale, les femmes rurales présentant des complications obstétricales ont accès à de nombreux prestataires de soins. Pourtant, beaucoup d’entre elles succombent. Utilisant les données d’études sur des femmes ayant demandé des soins obstétricaux d’urgence et les observations des participants sur les services de santé gouvernementaux, cet article dégage les facteurs de la persistance de taux élevés de mortalité maternelle à Koppal; faiblesse des systèmes d’information, discontinuité des soins, soutien insuffisant aux agents de santé, manque de rigueur des systèmes d’orientation des patientes et mécanismes biaisés de responsabilité. Par exemple, les décès maternels sont sous-notifiés et ne sont pas étudiés, les soins prénatals et les accouchements en milieu institutionnel ne sont pas liés aux soins post-partum ou obstétricaux d’urgence, et les agents de santé utilisent des injections contre-indiquées, sans vraiment traiter l’anémie ou la septicémie. Les familles perdent des ressources et un temps précieux pour consulter de nombreux prestataires, mais n’obtiennent pas de soins efficaces; elles en rendent responsables les agents de santé du niveau inférieur et les femmes pour n’avoir pas accouché dans un établissement de soins. Enfin, le rôle des administrateurs et des politiciens pour garantir des services de santé efficaces est dissimulé. Des réformes importantes de l’offre et de la demande sont mises en oeuvre mais elles n’associent pas constructivement les prestataires informels, pas plus qu’elles ne s’attaquent aux obstacles systémiques. Un profond changement administratif est nécessaire, faute de quoi de nouvelles allocations budgétaires seront gaspillées, sans parvenir à sauver la vie des femmes.

Resumen

A pesar de tener acceso a numerosos prestadores de servicios de salud en Koppal, el distrito más pobre del estado de Karnataka, en la India meridional, muchas mujeres rurales con complicaciones obstétricas continúan muriendo. Basado en estudios de casos de mujeres que buscan cuidados obstétricos de emergencia y en la observación participante en servicios de salud gubernamentales, este artículo destaca las limitaciones de la prestación de servicios implícitas en la persistencia de los altos índices de mortalidad materna en Koppal, por ejemplo: sistemas de información débiles, discontinuidad de los cuidados, trabajadores de salud sin apoyo, sistemas de referencia al azar y mecanismos distorsionados de responsabilidad. Por ejemplo, las muertes maternas son subreportadas y no revisadas, la atención antenatal y el parto institucional no son vinculados con los cuidados obstétricos posparto o de emergencia, y los trabajadores de salud utilizan inyecciones indebidas pero no tratan la anemia o sepsis. Las familias desperdician tiempo y recursos valiosos cuando acceden a muchos prestadores de servicios sin obtener cuidados eficaces, y la culpa recae en los trabajadores de salud de nivel inferior y en las mujeres por no tener un parto institucional. Por último, no queda clara la función de los administradores y políticos en garantizar servicios de salud en buen estado de funcionamiento. A pesar de que se están implementando importantes reformas relacionadas con la oferta y demanda, éstas ni implican constructivamente a los prestadores de servicios extraoficiales ni tratan las limitaciones sistémicas de la prestación de servicios. Se necesita un cambio administrativo fundamental, sin el cual nuevas distribuciones presupuestales serían derrochadas con poco impacto en los esfuerzos por salvar la vida de las mujeres.

In 1998, the main causes of maternal death in rural India were: anaemia (24%), bleeding in pregnancy and puerperium (23%), abortion (12%), eclampsia and toxaemia (10%), puerperal sepsis (10%), malposition of child leading to death of the mother (7%) and unclassified symptoms (14%).Citation1 These statistics reveal how preventable these deaths are. The interventions required to address the leading causes of death exist and are not technically complex if accessed in time. This makes the unsuccessful efforts by pregnant women in backward regions of India to obtain basic obstetric care even more tragic.

Gender bias in terms of failure to acknowledge pregnant women’s needs and failure to ensure accountability for women’s reproductive rights and survival are crucial factors sustaining high levels of maternal mortality.Citation2 Following such an analysis, in this article I focus on the service delivery constraints that obstruct repeated attempts by women and their families to access emergency obstetric care in Koppal district, the poorest district in Karnataka, south India.

Methodology

This article is derived from research undertaken through the Gender and Health Equity Project led by Gita Sen at the Indian Institute of Management Bangalore (IIMB) in collaboration with the Karnataka Health and Family Welfare Department and a women’s empowerment programme called Mahila Samakhya Karnataka (MSK). MSK, as the lead implementing partner, supports community-based activities that promote women’s rights to health through women’s groups in 60 villages. These 60 villages include approximately 82,000 people accessing eight primary health centres in Koppal and Yelburga talukas (sub-districts) of Koppal district.

Within this project area and as a part of the IIMB research team, I undertook nine months of participant observation of primary care level government service delivery and management, alongside semi-structured interviews with 13 medical officers, ten programme officers, eight senior district level officials and ten state level health department officials in 2004.

While living in Koppal, we realised that women’s deaths from obstetric emergencies were more common than anticipated. This led us to engage in impromptu investigations of maternal deaths as they occurred. Our attention to the events happening around us led to further joint investigations with a government Taluka Health Officer. Time was spent supporting government review efforts by observing supervisory meetings and accompanying the Taluka Health Officer while he interviewed families and health providers about the circumstances of each woman’s ordeal. We also followed up with health providers, family members and project staff involved in cases independently of the Taluka Health Officer.

Over six months, we documented the experiences of 12 women, nine of whom died. I documented seven cases of women seeking emergency obstetric care and my colleague, Aditi Iyer, documented one. The last four cases were reported through government review meetings, but were not followed up due to my departure from Koppal. These women were from varied class and caste backgrounds. What they had in common was their residence in the villages of rural Koppal, their development of obstetric complications and their access to Koppal’s many health providers.

Our enquiries were neither part of a study on women’s access to obstetric services nor a study on maternal mortality. Despite these limitations, the findings provide compelling information that illustrates the challenges faced by women in need of emergency obstetric care in Koppal. Our action–research findings were corroborated by the Taluka Health Officer and a private gynaecologist in Bangalore, before analytical summaries and training inputs were circulated to government personnel and decision-makers. Subsequent research articlesCitation2Citation3 removed personal identifying information on women, families and health providers for confidentiality reasons.

Field context

With just over one million people, Koppal district in northern Karnataka, south India, is primarily made up of a young population, living in drought-prone, agrarian communities. For many in Koppal, survival is based on daily wage labour and seasonal migration. In addition, adverse gender and caste hierarchies correlate with very poor educational levels. These axes of deprivation exacerbate multiple hardships that severely debilitate maternal health outcomes. For instance, in Koppal, 84% of rural women cohabit before they are 18 years old, 80% of rural women are illiterate compared to 48% of their husbands, 42% of all married women use family planning (41% being sterilised and 1% using other methods), 80% of rural women get some antenatal care but only 21% receive full antenatal care and 85% of rural women deliver at home.Citation4 For these reasons, in terms of social development Koppal is ranked at the bottom of all districts in Karnataka.Citation5

In terms of the health system, the private sector in the rural villages of Koppal consists of a large number of informal providers, ranging from spiritual and traditional healers, shopkeepers selling tonics and tablets, traditional birth attendants and rural medical practitioners.Footnote* Rural medical practitioners are private providers without formally recognised medical training. They primarily learn doctoring through apprenticeship, and although they have no legal permission to practise, they enjoy widespread recognition from villagers.

In contrast to the informal nature of the private sector at the village level, there are some formally qualified, higher-level services at the town level. One or two private specialists exist in each of the largest towns. They, along with their unspecialised doctor colleagues, run nursing homes or clinics that can treat general illnesses and undertake simple surgery. Government specialists and a few primary health centre doctors often form the allopathic backbone for these private clinics. There is no blood bank in the district in either public or private facilities, which precludes the possibility of surgical interventions for serious emergencies.

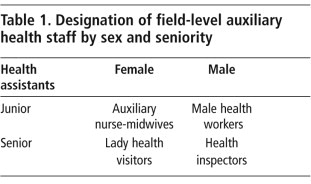

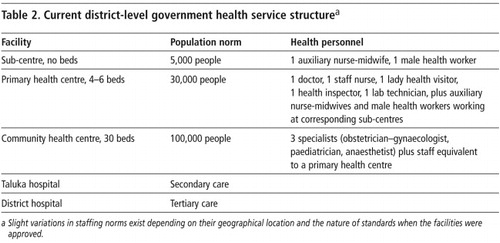

Alongside and interwoven with the private sector in Koppal is an extensive government network of health services. This public sector network is structured according to a hierarchy of services based in theory on population norms. Tables 1 and 2 show the structure of services, the health personnel they should have and the populations they serve.

In practice, neither the population norms nor the hierarchical structure of services are adhered to. Facilities have proliferated due to politicians sanctioning primary health centres and hospitals in their own constituencies and due to the availability of budget lines for infrastructural development. While there is political and administrative support for constructing facilities, less attention is paid to systemic operational problems that limit the functioning of services. For example, when I started my research in 2000, vacancies existed for roughly 33% of doctors, 29% of auxiliary nurse-midwives, 46% of male health workers and 52% of lady health visitors.Citation6 Although some of these vacancies have been addressed, not enough MBBSFootnote* doctors have responded to district-level contracting efforts. In addition, no community health centre in Koppal, either in 2000 or now, has any specialists.

In conclusion, Koppal’s health sector consists of a large number of informal providers in its villages, a small formally qualified private sector based in its larger towns and a significant government network based in villages and towns across the district. Regardless of the institutional environment (i.e. whether informal or formal, private or government), each segment of health service delivery suffers from quality of care problems that cripple its ability to respond to obstetric emergencies.

Repeated failure to obtain emergency obstetric care

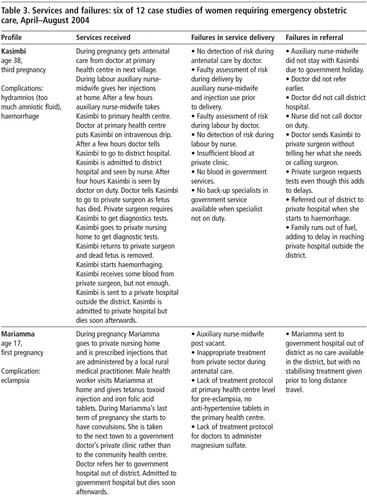

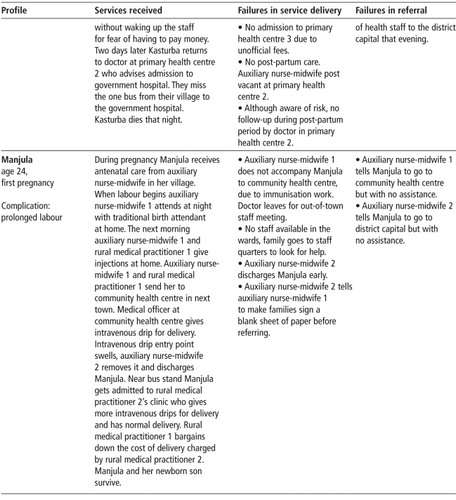

Within this plural health system, women repeatedly accessed informally and formally qualified health providers, located in government and private services, both in and outside the district at multiple points in time, but they still failed to get effective obstetric care. As a result, over a six-month period, nine of the 12 women whose case studies were documented died in spite of seeking care. Four women died of sepsis, two from haemorrhage, two from anaemia and one from eclampsia. The six case studies in Table 3 highlight the range of complications experienced, the range of health providers accessed, the services received and the systemic failures encountered.

Kasimbi saw eight different health care providers in the space of 24 hours and died of haemorrhage. Kusuma sought help from four different health care providers in the 48 hours leading up to the delivery of her stillborn child. None of them acknowledged her risk during delivery nor her need for post-partum care. She died of sepsis four days later. Even when health workers were aware of risk or co-morbidity, as in the cases of Mariamma and Kasturba, this did not lead to appropriate treatment or effective continuity of care.

Some of these deaths, like those of Kasimbi and Mariamma, can be explained by the lack of specialist services. However, these case studies also document systemic biases in the routine delivery of primary health care. Kasturba was recognised as suffering from severe anaemia but neither the medical officer nor the health assistant ensured that her condition improved either before or after delivery. Despite seeking an institutional delivery at a community health centre and returning for post-partum care, Durgamma still died from sepsis. Anaemia and sepsis can be dealt with at the primary health care level without the assistance of specialists, provided they are identified in time within a system that supports continuity of care.

Revealed failures in service delivery

Field observations revealed the following service delivery failings: weak information systems, discontinuity of care, unsupported health workers, haphazard referral systems and distorted accountability mechanisms.

Weak information systems

Although all deaths are supposed to be reported, this does not hold true for all maternal deaths. During the five months in which we reported ten maternal deaths from one taluka, the remaining three talukas of Koppal district did not report even one maternal death. In a rural study in Anantpur, in the neighbouring state of Andhra Pradesh, as many as 66% of maternal deaths had not been recorded by health providers.Citation7

Even when documented, the formats used by government services to report maternal deaths collect the barest biomedical and demographic details. This does not enable an analysis of where failures occurred and what could have been done to save the woman’s life. In Kusuma’s case, the details of her death were reviewed in less than five minutes at the end of a four-hour taluka meeting. The main outcome of the review was to ask the auxiliary nurse-midwife to correct some of the demographic information recorded. Some government officers report that there is a government order requiring a medical officer and higher-level officers to review each maternal death, but this is rarely done. Maternal mortality committees with dedicated staff and resources are conspicuously absent.

Discontinuity of care

The government’s approach to maternal health is based on two planks: antenatal care and institutional delivery. In theory, effective antenatal care should prevent the leading cause of maternal mortality in India: anaemia. In Koppal, 98% of pregnant women have some form of anaemia and 22% of pregnant women have severe anaemia.Citation4 However, even when health workers recognise severe anaemia in pregnant women, they don’t always ensure that the problem is addressed. In Kasturba’s case, severe anaemia was diagnosed during pregnancy by auxiliary staff and a doctor, but neither ensured that her anaemic condition improved during pregnancy. After delivery when she returned to the primary health centre, she was told to go to the district hospital. She died that same evening after having missed the one bus that links her village to the district capital. Government health workers made no attempt to ensure that Kasturba got care at the district hospital, despite their own access to other modes of transport.

The lack of follow-up provided to anaemic women is not due to a lack of work or supervision. Instead, existing monitoring routines are procedurally biased against supporting continuity of care. In all of the supervision meetings observed, supervisors asked health workers to report aggregate numbers of antenatal visits made, tetanus toxoid injections given, iron folic acid tablets dispensed and deliveries attended. Beneficiaries were defined by the number of health commodities given out and accountability was defined by whether health providers kept accurate stock records. The records document that work is being undertaken and patients receive visible products like injections and tablets. Whether women swallow the iron folic acid tablets given and whether their health is monitored to ensure a reduction in anaemia was never asked in any of the supervision meetings observed.

Prior to our enquiries into the maternal deaths, none of the routine supervision meetings observed mentioned post-partum care. The time period during which women face the most risk of an obstetric complication, during and after delivery, is also the phase during which they are most neglected in Koppal. Most women deliver at home, but few qualified health providers, whether from private or government, visit newly delivered women. Even if women go to government facilities for delivery, post-partum care is not assured. Kusuma and Durgamma sought institutional delivery and died due to sepsis several days later due to the lack of effective post-partum care.

These case studies also revealed that there is no back-up system for attending to women with potential emergency obstetric needs when other competing health or management tasks are at hand. The obstetric needs of the women we documented were neglected because doctors accorded higher priority to outpatient care, pulse polio campaigns, tubectomy camps and administrative meetings. Consultants hired by UNICEF and WHO regularly visit Koppal to monitor progress on general immunisation, polio, leprosy and tuberculosis, but there is no external monitoring for maternal health.

Although government officials emphasise the importance of institutional deliveries, concomitant efforts to ensure that this is followed up with post-partum care and backed up with emergency obstetric care fail to materialise on the ground. Programmatic norms acknowledge the importance of access to safe abortion, blood banks and specialist services, but none of these is readily available in Koppal. While a stress on antenatal care and institutional deliveries is not unimportant, if they are not integrated into a continuum of care that ensures access to emergency obstetric care, they are not sufficient to save women’s lives. All the maternal deaths we documented in Koppal included women who received antenatal care and lived within accessible distance of a sub-centre or primary health centre. Yet they died.

Unsupported health workers

In addition to failing to ensure continuity of care, the technical skills required to save women’s lives are not supported. Several of the case studies documented errors in technical judgement by both medical officers and health assistants. Medical officers did not assess Kusuma’s labour pains correctly or recognise Kasturba’s obstructed labour early enough. In another case study, severe anaemia was misdiagnosed as jaundice, and while reviewing the death of another woman due to sepsis, an auxiliary nurse-midwife explained that the woman died because she was too fat. Although Durgamma returned to the community health centre with symptoms of fever after delivery, she was treated symptomatically for malaria and died of sepsis several days later.

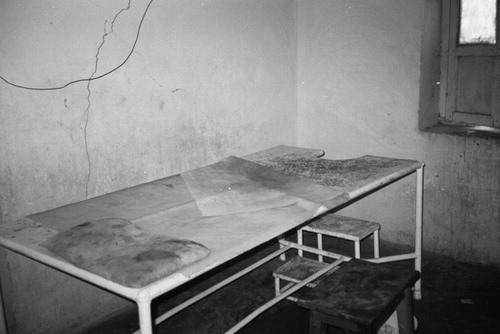

In Koppal, auxiliary nurse-midwives are not equipped to exercise effective diagnostic skills as basic equipment like blood pressure operators, stethoscopes and thermometers are not available at the sub-centre level. Nor are auxiliary nurse-midwives encouraged to take such initiative. A supervisor reported that auxiliary nurse-midwives are asked to keep an eye out for the Five Toos: Too late pregnancy (over the age of 35 years), Too early pregnancy (below the age of 15 years), Too short lady, Too many deliveries (over 5-8), Too anaemia (sic). Only the latter is a clinical diagnosis, and is not taken seriously by government officers.

What is perhaps most striking about the maternal deaths we documented in Koppal is not the lack of access to care, but the irrational or inappropriate care provided to women during delivery. Whether they are government doctors, auxiliary nurse-midwives or rural medical practitioners, health providers readily supplied injections or intravenous drips to women in labour. Rural medical practitioners reported using oxytocin, methargin, vitamin B and tetanus toxoid injections in varying sequences without necessarily knowing what stage of labour the mother was in. Even antenatal care is reduced to the distribution of commodities like iron and folic acid tablets and tetanus toxoid injections. In the absence of effective referral services to back government health workers up, and faced with competition from an unregulated market, health workers face a crisis of legitimacy. One avenue of self-defence is to provide visible markers of health care: tonics, tablets and injections, whether clinically required or not.

Haphazard referral systems

The case studies also demonstrate that referral in Koppal is a haphazard and risky endeavour, dependent on individual luck and bargaining power, rather than a mechanism that coordinates universal access to appropriate care. Even if the primary health centre doctor writes a letter, as in Kasimbi’s case, no one called the district hospital despite functioning phones to inform them of her need for a caesarean due to obstructed labour. Upon arrival, Kasimbi was told to wait by a nurse for four hours before a doctor arrived, who then sent them to a private surgeon, as the specialist had already left for the day. The private surgeon then referred Kasimbi to another private facility for diagnostic tests, adding to delays and costs. It is unclear whether this was clinically necessary. Rural medical practitioners reported kickbacks from private providers in the district capital to facilitate referral by rural medical practitioners and government doctors.

Even if government health providers are not adequately trained or supervised to respond to obstetric emergencies, they are more literate, socially entitled and administratively familiar with government facilities than the poor women and families who seek care during an obstetric emergency. Yet, women and families are routinely left to fall back on the unqualified advice of rural medical practitioners or traditional birth attendants, rather than any government personnel to ensure access to appropriate care. Consequently, women like Kasimbi, Mariamma, Kusuma, Kasturba and Durgamma and their families move with increasing desperation from health provider to health provider, even travelling out of the district at great expense, with tragic results.

Referral is more than a matter of logistics facilitating telecommunications, transport and roads. It is also a matter of accountability for assuring continuity of care for women and continuity of supplies and expertise for health providers. This means holding the first point of referral accountable for accompanying women in emergencies to the next health facility and also holding health administrators accountable for providing the required inputs to enable a functioning referral system to back up health providers.

Distorted accountability mechanisms

Yet this is not how accountability was observed to function. In Kusuma’s case, when I expressed concern about her death in a primary health centre review meeting, the auxiliary nurse-midwife got blamed for not filling in her antenatal register properly, even though this was not why Kusuma died. As observed through multiple review meetings and other kinds of supervision activities, accountability efforts routinely sought scapegoats to allocate blame, rather than attempt to resolve local problems constructively. As a result, health workers resorted to defensive practices, including advising colleagues to ensure that families signed blank papers before providing care, as in Manjula’s case.

To prevent further abuses of power, it is critical not to pin accountability solely on traditional birth attendants and auxiliary nurse-midwives. These under-skilled women, usually working in isolation, cannot address maternal mortality on their own. Mothers who experience complications in labour and post-partum need to be quickly transferred to specialists at higher levels of care. The reality of Koppal is that emergency obstetric services only exist on paper.

Ten years after the district was created, over a million people in Koppal are still waiting for reliable emergency obstetric services. While infrastructure, specialists and blood storage units have been approved, no administrator is held accountable for ensuring that these approvals translate into functioning services. Nor is any politician answerable for the sale in transfers that ensures little continuity of specialists or administrators in Koppal. Until these systemic issues that block the functioning of critical services are addressed, an exhortation to women to go for institutional delivery serves as a dangerous distraction, wasting valuable resources with little impact on outcomes.

Current scenario: some changes, many challenges

Since 2004, some changes have taken place in Koppal. Most notably, Kusuma’s story was converted into a street theatre campaign spearheaded by IIMB project team members mobilising change, village by village. In conjunction, IIMB project staff in Koppal continue to document emergency obstetric cases as they occur. Although not all maternal deaths are avoided, several emergency obstetric cases have become near-miss cases. Each near-miss has buoyed further awareness and spurred action by women, families, local volunteers, community leaders, health workers and project staff to support referral through faster decision-making, provision of finances and assurance of transport.

Although gender biases that downplay the importance of women’s health within households remain important, the main challenges to realising safe motherhood in Koppal remain with health service delivery. As mentioned, while blood storage units and further infrastructure have been approved, this does not mean that blood and specialist services are available in Koppal. Lucrative market rewards for specialist skills make it particularly difficult to recruit or contract specialists in backward districts like Koppal. Nonetheless, efforts to address anaemia or ensure post-partum visits, which do not require specialist care, are also not being supported.

Karnataka in 2006 launched the National Rural Health Mission, a national programme already being implemented in other parts of the country, increasing allocations to health care. It includes the Reproductive and Child Health II programme and promises important investments in the provision of emergency obstetric care: training doctors in emergency skills, upgrading skills of auxiliary nurse-midwives to ensure skilled birth attendance, four blood storage points in every district, contracting of specialists and upgrading community health centres to meet national standards. It also supports demand-side financing to spur utilisation of services. Women and village-level volunteers are provided financial incentives for assisted home deliveries, institutional deliveries and caesareans.

Despite the potential for change two main concerns remain in Karnataka. First there is no official recognition of the positive role that rural medical practitioners play in referral, nor any effort to constructively address their negative role in the irrational use of injections during labour. Yet their use of injections entails serious health risks, unnecessary expense and has knock-on effects on what government health providers are expected to do in order to gain community respect. Standard policing efforts that outlaw rural medical practitioner practice are ineffective. Efforts must focus on constructively ensuring their positive role in terms of referral and health education, while changing their role in terms of clinically irrational but financially and socially desirable injections. While Karnataka proudly pursues contracting measures with private providers who are formally qualified but hardly available in backward districts, attention must also be paid to these informal providers who are widespread in backward districts.

Secondly, despite the importance placed on decentralised, needs-based, district-level planning, significant state and central government control remains through the budgeting process. Although more budget support for staffing was provided for northern districts, which have greater need, community health centres are upgraded and doctors trained in emergency obstetric skills on an arithmetical basis (two for every district). Most importantly, managerial changes required to improve service delivery concerns (information systems, continuity of care, health worker support, functioning referral systems and accountability that promotes trust) lag behind, while activities that are easier to budget and disburse (infrastructure and financial incentives) move ahead. Yet if administrators and politicians cannot address these service delivery constraints that go beyond budgeting, increased allocations for health care and valuable gains made for realising safe motherhood in terms of community mobilisation and health worker trust will be squandered.

Acknowledgements

The support of Gita Sen and Aditi Iyer, as colleagues at the Indian Institute of Management Bangalore, has been invaluable. The assistance of the Gender and Health Equity Project staff and that of the District Health Office in Koppal is also gratefully acknowledged. Funding for this work was provided by the Swedish International Development Agency and the John D and Catherine T MacArthur, Rockefeller and Ford Foundations.

Notes

* These providers are also known as registered medical practitioners (RMPs); however they stopped being registered many years ago.

* MBBS stands for Bachelors in Medicine and Bachelors in Surgery. It is the five-year course offered at the graduate level for allopathic medicine in Commonwealth countries. India also has doctors trained in Ayurveda, Homeopathy, Unnani, Siddha and Yoga, who can practise in primary health centres.

References

- Table No. 11.05: Number and percentage distribution of deaths by causes under “child birth and pregnancy” (maternal deaths) by specific causes, their percentage to total deaths, total female deaths and female deaths under the reproductive age group 1997 and 1998. At: <www.cbhidghs.nic.in/hii2003/11.05.htm>. Accessed 1 August 2007

- A George, A Iyer, G Sen. Gendered health systems biased against maternal survival: preliminary findings from Koppal, Karnataka, India. Institute of Development Studies Working Paper 253. 2005; IDS: Brighton.

- A George. The outrageous as ordinary: maternal mortality and health workers’ perspectives on accountability in primary health care in Koppal district, Karnataka state, India. DPhil dissertation. 2007; Institute of Development Studies, University of Sussex: Brighton.

- International Institute for Population Sciences. Reproductive and Child Health District Level Household Survey (DLHS-2) India 2002-04. Round 2 Phase 1: Koppal. 2006; International Institute for Population Sciences: Mumbai.

- Government of Karnataka. Human Development in Karnataka. 2006; Planning Department, GOK: Bangalore.

- Personal communication, Koppal District Health Officer, 2000.

- JC Bhatia. A Study of Maternal Mortality in Anantpur District, Andhra Pradesh, India. 1989; Indian Institute of Management Bangalore: Bangalore.