Abstract

In 1997, the Supreme Court of India recognised sexual harassment in the workplace as a violation of human rights. However, little is known about the extent or persistence of sexual harassment. To obtain an understanding of women’s experiences of sexual harassment in the health sector, an exploratory study was undertaken in 2005–2006 among 135 women health workers, including doctors, nurses, health care attendants, administrative and other non-medical staff working in two government and two private hospitals in Kolkata, West Bengal, India. Four types of experiences were reported by the 77 women who had experienced 128 incidents of sexual harassment: verbal harassment (41), psychological harassment (45), sexual gestures and exposure (15), and unwanted touch (27). None of the women reported rape, attempted rape or forced sex but a number of them knew of other women health workers who had experienced these. The women who had experienced harassment were reluctant to complain, fearing for their jobs or being stigmatised, and most were not aware of formal channels for redress. Experiences of sexual harassment reflected the obstacles posed by power imbalances and gender norms in empowering women to make a formal complaint, on the one hand, and receive redress on the other.

Résumé

En 1997, la Cour suprême de l’Inde a reconnu le harcèlement sexuel au travail comme une violation des droits de l’homme. Néanmoins, l’étendue ou la persistance du harcèlement sexuel sont mal connues. Une étude exploratoire a été menée en 2005 auprès de 135 femmes (médecins, infirmières, agents de santé, personnel administratif ou non) travaillant dans deux hôpitaux publics et deux hôpitaux privés à Kolkata (Bengale occidental), pour comprendre l’expérience du harcèlement sexuel chez des femmes du secteur de la santé. Quatre types d’expériences ont été notifiés par les 77 femmes qui avaient connu 128 épisodes de harcèlement sexuel : harcèlement verbal (41), harcèlement moral (45), exhibitions et gestes sexuels (15) et attouchements indésirables (27). Aucune des femmes n’avait signalé de viol, de tentative de viol ou de rapports sous la contrainte, mais un certain nombre d’entre elles connaissaient d’autres femmes travaillant dans le secteur de la santé qui en avaient été victimes. Les femmes qui avaient connu des épisodes de harcèlement hésitaient à se plaindre, craignant de perdre leur emploi ou d’être stigmatisée, et la plupart ne connaissaient pas les filières officielles pour obtenir réparation. Les expériences de harcèlement sexuel révèlent les obstacles que constituent les déséquilibres de pouvoir et les normes différentes selon les sexes pour donner aux femmes les moyens de porter plainte, d’une part, et d’obtenir réparation, de l’autre.

Resumen

En 1997, la Suprema Corte de la India reconoció al acoso sexual en el trabajo como una violación de los derechos humanos. Sin embargo, se conoce poco sobre la incidencia o persistencia del acoso sexual. A fin de adquirir un entendimiento de las experiencias de mujeres con el acoso sexual en el sector salud, se realizó un estudio exploratorio en 2005 entre 135 mujeres trabajadoras de salud: médicas, enfermeras, profesionales de la salud, administradores y otro personal no médico que trabajaba en dos hospitales gubernamentales y dos privados en Kolkata, Bengal Occidental, en la India. Cuatro tipos de experiencias fueron reportadas por las 77 mujeres que habían experimentado 128 incidentes de acoso sexual: acoso verbal (41), acoso psicológico (45), exposición y gestos sexuales (15), y toque indeseado (27). Ninguna de las mujeres denunciaron violación, intento de violación o sexo forzado, pero varias conocían a otras mujeres trabajadoras de salud que habían sufrido estas experiencias. Las mujeres que experimentaron acoso estaban renuentes a quejarse por temor a perder su trabajo o ser estigmatizadas, y la mayoría no era consciente de los medios oficiales de reparación. Las experiencias de acoso sexual reflejaron los obstáculos producidos por desequilibrios de poder y normas de género para empoderar a las mujeres a entablar una denuncia oficial, por un lado, y recibir reparación por otro.

Over the past two decades, sexual harassment has become an issue of increasing concern globally. Sexual harassment encompasses overt physical behaviour, such as rape and unsolicited physical contact, as well as verbal conduct such as jokes of a derogatory nature, use of threatening or obscene language, proposals of a sexual nature, or the offer of offensive materials such as pornographic pictures, which may reasonably be perceived to create a negative psychological and emotional work environment.Citation1 Sexual harassment is unwanted by or offensive to the person to whom it is directed. In many cases, including in the workplace, the person being harassed may not be able to withdraw from the situation easily or have recourse to help to stop or censure the offender.Citation2

The sparse evidence from India on sexual harassment in the workplace is instructive. In one survey of women working in different sectors in Kolkata, 95% of respondents agreed that sexual harassment was a workplace reality, including pressure from a superior for sexual favours, stalking and physical comments.Citation3 Likewise, a study conducted by Lal Bahadur Shastri Institute in 2000 found that 21.4% of women civil servants felt sexual harassment was on the increase in premier government jobs.Citation4 Other evidence suggests that sexual harassment is experienced by large numbers of women in the workplace and is typically perpetrated by a person in a position of authority. The majority of women do not take action or lodge an official complaint for fear of being dismissed, losing their reputation or facing hostility or social stigma in the workplace.Citation5–8

In 1997, the Supreme Court of India recognised sexual harassment in the workplace as a violation of human rights. The landmark Vishaka judgement outlined a set of guidelines on how to handle sexual harassment in the workplace.Citation9 These guidelines placed the responsibility on employers to provide a safe work environment to their women employees, including both preventive and remedial measures. Little is known, however, about the extent to which women continue to experience sexual harassment in the workplace or whether these guidelines have had an effect.

The objective of the study reported here was to explore women’s experiences and perceptions of sexual harassment in hospital settings in Kolkata, West Bengal, India, as well as experiences of others about which women were aware, the nature of any action taken to seek redress, and the extent to which the women were aware of the complaint mechanism outlined in the Vishaka judgement.

The health sector is an appropriate setting for a study of sexual harassment. Although the level of violence against health care workers is largely undocumented in India, evidence from developed countries highlights the prevalence of sexual harassment in the health sector, the power imbalances and vulnerable working conditions of women workers that perpetuate harassment. Nurses, medical students and young residents have all been observed to be vulnerable to sexual harassment.Citation10 Nurses, for example, have reported victimisation by both physicians and patients.Citation11 These reports highlight the hierarchical nature of the health sector as a workplace and the high stakes if vulnerable women workers choose to challenge a supervisor’s behaviour.

In India, too, the health sector is hierarchical and power imbalances between women and men in West Bengal, and in India generally, are wide. There were, for example, a total of 28,079 nurses registered with the West Bengal Nursing Council in 2005, of whom only 71 were men. In comparison, of the 48,637 medical practitioners (allopathic) registered with the West Bengal Medical Council in 2005, the vast majority (84%) were men.Citation12 Such disparities raise the possibility of sexual harassment in the health sector.

Study design and participants

Sexual harassment is a sensitive issue with few research precedents; the methodology adopted in this study was entirely qualitative. The study was conducted in four hospitals, two government and two private, in Kolkata in 2005-2006. The government hospitals are large tertiary hospitals with around 1,600–1,700 beds; the private hospitals have around 350 beds each.

The Department of Health, Government of West Bengal, was approached for permission in two of the large hospitals where the study was conducted. This was followed by permission from authorities in the individual hospitals. These two hospitals were selected as they offer a range of services and are amongst the largest in the city. In the private sector almost all the large hospitals (24 in total) were approached and of these, two gave permission for the research. Department heads in the hospitals were then approached and requested to provide access to staff through their respective supervisors. All those on duty on the days on which research was conducted were informed of the study and requested to participate. It took about two months’ time to complete all the interviews. 135 of 141 health workers approached gave consent (though most were hesitant to give written consent); the rate of refusal was the same in all the hospitals. The number of respondents interviewed in each hospital was not necessarily proportional to the number of women employees.

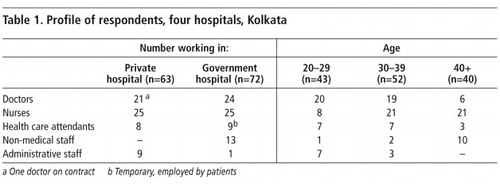

A total of 135 women were interviewed in-depth over a period of 11 months, of whom 38 and 34 respondents were from the two government hospitals and 29 and 34 from the two private hospitals. A description of their professional status and ages are provided in Table 1 . They had worked from one to more than seven years in the institution in which they were interviewed, and all but one doctor and nine health care attendants (the latter employed by patients) were permanent employees.

Interviews were conducted by the principal investigator and/or her research associates. All interviewers had undergone extensive training in conducting in-depth interviews and transcribing textual data. Interviews were conducted in the workplace. In the case of nurses, the nursing supervisor would vacate their room for the interview. For non-medical staff in government hospitals the ward master would provide their room. Many of the doctors had their own cubicles where the interviews could take place. One private hospital provided a designated place for the interviews. Complete privacy was ensured for all interviews, and interviews were terminated if this was not guaranteed. Interviews were in most cases conducted in one session, but in rare cases ran over two sessions. Detailed notes were taken. Data were analysed using Atlas-Ti, using a coding structure developed to identify, among other issues, types of harassment experienced, redress sought and obstacles perceived in lodging complaints.

Experiences of sexual harassment in the workplace reported

By and large, the topic of sexual harassment was initially met with discomfort, denial and fear of reprisals, as well as some judgmental attitudes about women provoking such incidents. Further probing suggested that most of the women perceived sexual harassment as normal behaviour, an occupational hazard and even harmless. Those who were employed on daily wages or on contract were particularly reluctant to engage with this issue and expressed initial hesitation to talk about harassment for fear of repercussions.

Although many women did not initially acknowledge the incidence of sexual harassment in their workplace or perceive it to be a key concern, on further probing, a range of experiences were reported. Drawing from women’s own descriptions, the experiences fall into three broad categories:

| • | Verbal harassment – comments that have sexual overtones, or personal remarks that are humiliating and of a sexual nature. | ||||

| • | Psychological harassment – (a) intimidation and anxiety-provoking behaviours, such as, insistence on accompanying the respondent, phone calls at odd hours, stalking or following the respondent, staring at her breasts and sending obscene text messages; and (b) sexual gestures and exposure, including incidents in which the perpetrator intentionally falls onto a woman, exposes his penis to her, stands up naked or masturbates, and in the case of patients, insists that the health worker massages or sponges his body or wipes his private parts even when he is able to do so himself. | ||||

| • | Physical harassment – (a) unwanted pinching, grabbing, hugging, embraces, patting, brushing against a woman, touching her breast or other parts of the body; and (b) rape, attempted rape or forced sex.Citation1Citation9 | ||||

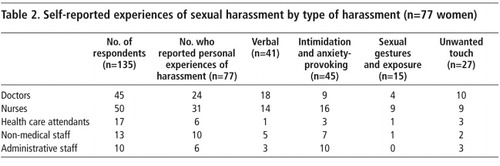

Of the 135 women interviewed, 77 reported that they had experienced some form of sexual harassment in their current or previous workplace. Twenty-eight women reported more than one experience of sexual harassment, including nine doctors, ten nurses, one health care attendant, four non-medical staff and four administrative staff. Most often reported were experiences of intimidation and anxiety-provoking harassment, followed by verbal harassment, unwanted touch and sexual gestures and exhibitionism (Table 2). None of the respondents reported having been raped. However, five women reported cases of others who had been raped or experienced attempted rape in a health facility.

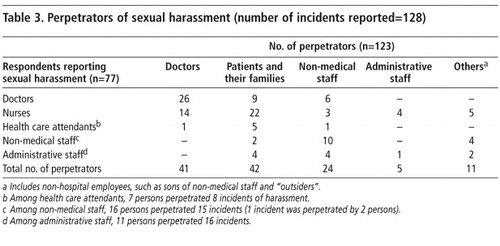

Perpetrators included doctors, non-medical and administrative staff and people from outside the hospital (Table 3). Patients and members of their families were often among the perpetrators of sexual harassment of staff in these hospitals, and junior doctors and nurses in particular reported experiences of and fears of sexual harassment at the hands of this group.

Verbal harassment

A number of studies conducted outside India suggest that verbal harassment tends to be the most common form of sexual harassment,Citation1Citation2 include calling women offensive names, making comments about clothing and looks, and jokes of a sexual nature, intended to embarrass the woman. This study supports this finding. Forty-one of 77 respondents reported verbal harassment by the whole range of perpetrators. Comments about dress were very common. The majority of those reporting verbal harassment were young doctors and nurses, notably those in the age group 25–35. Comments were described as humiliating and in some cases resulted in women discontinuing their course of further study.

“Once I wore a kurta [shirt]. One of my colleagues said, ‘This print is like a pillow cover.’ Then another joined in saying, ‘Only if I use it as a pillow, will I know how soft it is.’” (Doctor, age 32, government hospital)

In a few instances, young doctors also reported sexual harassment from patients’ families, often in connection with perceived negligence over treatment of patients. Experiences ranged from taunts to intimidation and threats:

“One person came to me with a stab injury. He and all those who were accompanying him were drunk and very unruly. I had an argument with them. Then they said, ‘Remember you are a girl and should behave like a girl, the night is still young, and we will come back with medicine and then see to you.’” (Doctor, age 29, government hospital)

Nurses reported verbal harassment from every category of respondent, notably those perceived to be in a position of authority. Nurses noted that verbal harassment from doctors tended to be indirect and subtle:

“I was posted in an area where girls marry very early. Many of them come with post-coital injury after marriage. It became a common joke amongst the doctors to say, ‘Call us at night only if there is a post-coital injury.’” (Nurse, age 30, government hospital)

Nurses frequently reported harassment, moreover, from patients and their families, non-medical staff and outsiders. In contrast, non-medical and administrative staff rarely reported that they were harassed by doctors. Much of the harassment they experienced was perpetrated by other non-medical staff with whom they had more contact:

“One ward boy told an attendant, ‘You have got such ripe guavas.’” (Non-medical staff/senior attendant, age 36, government hospital)

Psychological harassment

Psychological harassment can involve relentless proposals of physical intimacy, beginning with subtle hints and leading to overt requests for dates or sexual favours. Psychological harassment such as exhibitionism can endanger the individual’s performance or undermine her sense of personal dignity.Citation1Citation7

Experiences of intimidation and anxiety-provoking harassment were reported by all categories of respondents. Perpetrators were frequently those who held positions senior to those of the victims, but in a large number of cases they were male colleagues who held positions of equal authority but exerted power by virtue of their sex. For example, doctors reported psychological harassment by a senior consultant or a male colleague:

“I was working as an intern with a senior dentist. My senior was in his 70s. One day he called me and asked whether I would like to look at some good books. I asked him what books? He then showed me pornographic books. I was so embarrassed…I simply stopped going to that place.“ (Doctor, age 25, private hospital)

Nurses reported that a doctor would call them into their room alone at night, make the nurse sit with him without any work or continuously stared at her. Nurses spoke about doctors creating situations that they found difficult to handle:

“One doctor comes every day to the ward at late hours for his rounds; I am supposed to accompany him. When we go to a critical ward, he invariably asks me to remove the pants of a patient. Then he asks me to check the tension of the thigh muscles and the reflexes; these things can be done in the morning but he makes me do it at night. More importantly he does not watch the patient but looks at my face to see if he can arouse me.” (Nurse, age 33, private hospital)

Patients and their families were described, in contrast, as harassing nurses by calling them unnecessarily and repeatedly, and asking them to accompany them over drinks or to watch pornographic films:

“Some patients ask us to pour them a drink or sit with them and keep them company. They watch pornographic films on television at night; they call us to their room and ask us to sit and watch with them.” (Nurse, age 33, private hospital)

Sexual gestures and exposure

In a number of narratives, women reported that men exposed themselves in front of them or deliberately made gestures of a sexual nature. Respondents thought that this kind of harassment was particularly associated with the health sector, where physical contact or touch are necessary components of the job. This kind of harassment was mainly attributed to patients, and nurses were largely the ones who experienced it, and in a few instances, health attendants:

“They [patients] ask us to keep wiping their bottom even when it is clean.” (Nurse, age 33, private hospital)

Physical harassment

Experiences of unwanted touch were reported largely by younger doctors, nurses, hospital attendants and non-medical staff. A large number of doctors and nurses reported that the perpetrator was a senior doctor or consultant:

“In the operating theatre there is a particular doctor who will always ask for accessories from the women doctors. He will stretch out his hand in such a way that it will brush against the woman’s breast. At times we have to bend over to attend to the patient. Then he will put his hand on our bottom.” (Doctor, age 35, government hospital)

“After an open heart surgery a patient is kept in the observation room adjacent to the operating theatre. The sister has to stay there with the patient for some time. The doctor is not supposed to visit the patient unless he is called for. One day when I was in the observation room adjusting some equipment attached to a patient, a senior doctor came in and embraced me from the back. I could not move my hand as then the patient’s life would have been at stake. So I continued doing what I had to till he released me.” (Nurse, age 36, government hospital)

Nurses and a few doctors reported experiencing unwanted touch by patients and their families. Incidents included brushing against the body, pinching the buttocks, poking the breasts and trying to hold their hand.

Rape and attempted rape

Forced sex is likely to be particularly under-reported. Indeed, none of the respondents in our study reported having been raped or experiencing attempted rape in their current or previous workplace. However, five women reported that they were aware of incidents of rape occurring in their institutions, which included three nurses who were said to have been raped by members of the non-medical staff. After two of these three incidents, the perpetrator was apparently not dismissed; there was no information re dismissal as regards the third case. In the other two incidents, two non-medical staff were said to have been raped, one by a doctor and one by a senior administrative staff.

Power imbalances between perpetrators and women experiencing harassment

An analysis of the profile of perpetrators indicates that harassment is carried out by those who have seniority at work, e.g. senior doctors, but also those who have power because of their being male. This explains the harassment of female doctors and nurses by male non-medical and administrative staff. The male perpetrators tended to be in more powerful socioeconomic positions than the women – either in the same profession (senior vs. junior doctors) or in different professions (doctors vs. nurses) or by virtue of their status within the health facility (patient vs. staff member). Underlying all of these were huge gender inequities that sometimes appeared to supersede other power relationships, e.g. in the case of male patients or administrative staff harassing nurses, young male doctors harassing their female colleagues or non-medical staff such as stewards, sweepers, peons and ward boys harassing their female peers.

The most vulnerable of all women employees in the hospital setting, as a result, were the nurses, and some of them recognised this. Administrative staff took advantage of their position to harass nurses when they came to them regarding updating of their files, leave records, maternity benefits, etc. Even non-medical staff – most junior in the hierarchy – did not hesitated to harass the nurses.

Seeking help and redress: obstacles

Although a large number of incidents of sexual harassment were experienced, only 27 of the 77 women took any formal action to seek redress. Indeed, when probed, women tended to report that instead of complaining, they developed other coping mechanisms, ranging from sharing experiences of harassment informally with their colleagues to changing their dress habits.

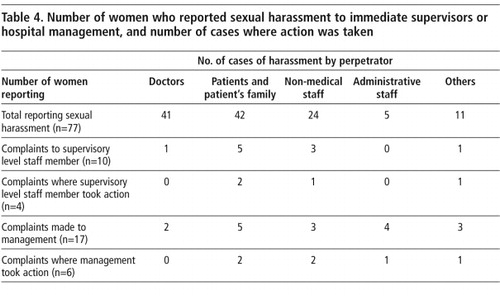

Only 10 respondents complained to their supervisors and 17 others to management (Table 4). Although a large number of perpetrators were doctors, victims were clearly reluctant to register complaints against this powerful group. Only three complaints were made against doctors (one to a supervisor and two to management) and no action was taken in any of these cases. Complaints that were registered were largely against patients and their families and non-medical staff. Action was also more likely to be taken by a manager if the perpetrator was in a relatively junior (non-medical staff) or economically deprived (patients) position. Of the 17 respondents who reported an incident to management, action was taken in only six instances, in all of which the perpetrator was a non-medical staff member. Where formal action was taken, it was likely to be direct. For example, of the three complaints made by nurses against non-medical staff, the management took action in two cases, either scolding or dismissing them.

In all other cases where action was taken, the supervisor took only informal action. Particularly if the perpetrator was a doctor, the supervisor tended to take a non-confrontational stance, typically making efforts to ensure that the victim was not exposed to the perpetrator or placed in a similar situation again. For example, nurses (the majority of those who complained) reported that when they had complained to a nurse supervisor about harassment from a doctor, the nurse would help her to keep a distance from the harasser.

“I know of patients who expose themselves and then call the nurse; they do this at night. When we receive such complaints, we ask the nurse to attend to the patient in a group.” (Nurse, age 36, private hospital)

Such actions were generally short-term efforts intended to tide over a particular situation rather than address sexual harassment more generally. As one woman reported, when action was taken, the harasser stopped harassing her but continued to engage in sexual harassment of others.

Thus, it appears that it was not necessarily the gravity of the offence but the profile of the perpetrator that decided whether action was taken and to what extent. Hence, doctors, whatever the nature of their offences, were not rebuked. Finally, neither supervisors nor, more importantly, those in authority set up committees as mandated by the Vishaka guidelines to inquire into the complaints.

Factors underlying non-action

Three major factors inhibited 50 of the 77 women from reporting the harassment: social norms that blame the victim, lack of awareness of their rights and, above all, recognition of power dynamics and the implications in terms of job security and risk of dismissal.

Sexual norms continue to blame women for provoking harassment, on the one hand, and perceive certain forms of behaviour to be normal among men, on the other. Many young women reported that they did not complain because they feared being blamed for provoking the incident or feared the loss of their reputation if they complained:

“They keep quiet as they fear that their families will get to know about it. Others might blame them saying that they had provoked the incident. If the girl is unmarried then it will be difficult to get her married.” (Nurse, age 35, government hospital)

Compounding these social norms are unequal power dynamics. Respondents were well aware that if the perpetrator was a person in authority, action was unlikely to be taken against him. Many reported fear of dismissal, loss of income, blocking of promotion and victimisation in work assignments (for example, inconvenient duty hours). Those on temporary contracts and those in the private sector especially expressed these fears. Several respondents reported that withdrawing from an unacceptable situation was preferable to lodging a complaint.

“As I told you I believe that the medical fraternity is very strong. We doctors know it too well and nobody wants to jeopardise careers at the beginning by being rebellious. Such things have to be accepted as part of life.” (Doctor, age 31, private hospital)

Moreover, in view of the importance of income from patients, action is unlikely to be taken against them either, and as they are not employees, their harassment does not fall within the ambit of the Vishaka guidelines.

Few respondents (20 of 135) were aware of the Vishaka guidelines on sexual harassment, and none knew of a hospital complaints committee for redress of complaints. Most respondents were sceptical about the potential effectiveness of institutionalised forms of redress, the functioning of such a complaints committee, or how it might be constituted.

“No one in a hospital is more powerful than the doctors… If doctors spread a bad word about a hospital, the hospital will find it difficult to get doctors to work there.” (Doctor, age 33, private hospital)

Conclusions

This study confirmed the persistence of sexual harassment among women working in the health sector. Power dynamics in the hospital setting make working women – notably nurses, junior doctors and non-medical staff – particularly vulnerable to victimisation if not outright dismissal, and fear of these consequences inhibits women from making formal complaints. Finally, women tended to lack awareness of formal complaints mechanisms or had little confidence in their impartiality. Indeed, their narratives suggest that hospital authorities may not know of or take the Vishaka guidelines seriously; that impartial committees to take complaints have not been established; that commercial interests override other matters in determining action against influential perpetrators; and that women who experience harassment are often doubly harassed if they opt to lodge a formal complaint.

These findings call for appropriate implementation mechanisms that recognise the obstacles posed by power imbalances and gender norms, and the need to empower women to make a formal complaint and be confident of receiving appropriate redress. A significant challenge lies in translating the Vishaka guidelines into operative tools for women employed in the health sector, to raise awareness among them of their rights, enable them to seek sensitive counselling to overcome feelings of helplessness and job insecurity, and lodge complaints appropriately. At the same time, programmes need to raise awareness among potential perpetrators of harassment – notably doctors and senior management – about the consequences of sexual harassment. Finally, at institutional level, programmes must ensure that complaints will be taken seriously and treated impartially, be they directed against doctors and other employees or patients and their families.

Acknowledgments

This is an edited and abridged version of the report of a project undertaken as part of the Health and Population Innovation Fellowship, awarded to the author in 2004, administered by the Population Council, New Delhi and is a continuation of the MacArthur Foundation’s Fund for Leadership Development. This paper has been possible with the guidance of Shireen Jejeebhoy, Senior Programme Associate, and others at Population Council. I thank Soma Sen Gupta, Director of Sanhita and Shalini Gupta for their support.

References

- I Jaising. Laws Relating to Sexual Harassment at the Workplace. 2004; Universal Law Publishing Co Pvt Ltd: New Delhi.

- R Collier. Combating Sexual Harassment in the Workplace, UK. 1995; Open University Press: Buckingham.

- Sanhita. Politics of Silence. 2001; Sanhita: Kolkata.

- MP Kumar. No End to Harassment. Women’s Feature Service. Ref. IND C 505. At: <www.wfsnews.org>. Accessed 31 July 2007

- A Kapoor. Women Workers’ Rights: A Reference Guide. 1999; International Labour Organisation: New Delhi.

- National Commission for Women. Study to Access the Harassment of Women at Work in Organized and Unorganized Sector. Report. New Delhi: Santek Consultants Pvt Ltd. (Undated)

- Saheli. Another Occupational Hazard: Sexual Harassment and the Working Women. 1998; Saheli Women’s Resource Centre: New Delhi.

- M Ramanathan, P Sankara Sarma, R Sukanya. Sexual harassment in the workplace: lessons from a web-based survey. Indian Journal of Medical Ethics. 2(April—June): 2005 At: <www.issuesinmedicalethics.org/132oa047.html>. Accessed 31 July 2007

- Supreme Court of India. Guidelines on Sexual Harassment at Workplace. Writ Petition Nos. 666 070 of 1992 decided on August 13, 1997. p.9.

- V de Martino. Relationship between Work Stress and Workplace Violence in the Health Sector. (ILO/ICN/WHO/PSI). 2003; International Labour Organization: GenevaAt: <www.ilo.org/public/english/dialogue/sector/papers/health/stress-violence.pdf>. Accessed 31 July 2003

- MP Bender. Sexual harassment in nursing. Journal of Advanced Nursing. 25(1): 1997

- Government of West Bengal. Health on the March 2005–2006. 2006; Government of West Bengal: Kolkata, 236.