Abstract

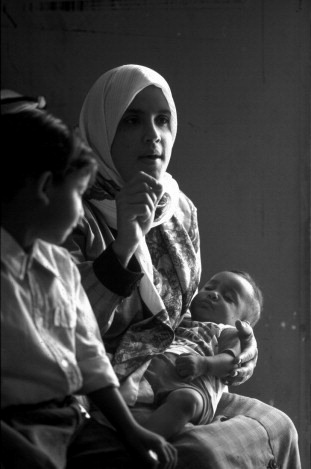

The purpose of this study was to assess the quality of maternity care in a large, public, Palestinian referral hospital, as a first step in developing interventions to improve safety and quality of maternity care. Provider interviews, observation and interviews with women were used to understand the barriers to improved care and prepare providers to be receptive to change. Some of the inappropriate practices identified were forbidding female labour companions, routine use of oxytocin to accelerate labour, restriction of mobility during labour and frequent vaginal examinations. Magnesium sulfate was not used for pre-eclampsia or eclampsia, and post-partum haemorrhage was a frequent occurrence. Severe understaffing of midwives, insufficient supervision and lack of skills led to inadequate care. Use of evidence-based practices which promote normal labour is critical in settings where resources are scarce and women have large families. The report of this assessment and dissemination meetings with providers, hospital managers, policymakers and donors were a reality check for all involved, and an intervention plan to improve quality of care was approved. In spite of the ongoing climate of crisis and whatever else may be going on, women continue to give birth and to want kindness and good care for themselves and their newborns. This is perhaps where the opportunity for change should begin.

Résumé

Cette étude souhaitait évaluer la qualité des soins obstétricaux dans un grand hôpital public palestinien, pour préparer des interventions destinées à améliorer la sécurité et la qualité des soins obstétricaux. Des entretiens avec le personnel de santé, l’observation et des entretiens avec des femmes ont permis de cerner les obstacles à l’amélioration des soins et de préparer les prestataires à être réceptifs au changement. L’interdiction des accompagnantes pendant l’accouchement, l’utilisation généralisée d’ocytocine pour accélérer le travail, la restriction de la mobilité de la parturiente et la fréquence des examens vaginaux figuraient au nombre des pratiques impropres. Le sulfate de magnésium n’était pas utilisé pour la pré-éclampsie ni pour l’éclampsie, et les hémorragies du post-partum étaient fréquentes. Une grave pénurie de sages-femmes, la supervision insuffisante et le manque de compétences conduisaient à des soins inadaptés. L’utilisation de pratiques à base factuelle qui encouragent le travail normal est essentielle dans les milieux pauvres en ressources et où les femmes ont de nombreux enfants. Le rapport de cette évaluation et les réunions avec les prestataires de soins, les administrateurs hospitaliers, les décideurs et les donateurs ont montré la réalité à toutes les parties prenantes, et un plan d’intervention pour améliorer la qualité des soins a été approuvé. En dépit du climat actuel de crise, et quels que soient les événements qui les entourent, les femmes continuent d’accoucher et de vouloir des soins de qualité, à l’écoute des mères et des nouveau-nés. C’est peut-être là que doit commencer le changement.

Resumen

El propósito de este estudio fue evaluar la calidad de la atención de maternidad en un importante hospital público de referencia palestino, como el primer paso para formular intervenciones a fin de mejorar la seguridad y calidad de la atención de maternidad. Se realizaron entrevistas con los prestadores de servicios, observaciones y entrevistas con las mujeres para entender las barreras a una mejor atención y preparar a los prestadores de servicios para estar abiertos al cambio. Algunas de las prácticas indebidas encontradas fueron la prohibición de acompañantes durante el parto, el uso rutinario de oxitocina para acelerar el parto, la restricción de movilidad durante el parto y exámenes vaginales frecuentes. No se utilizó el sulfato de magnesio para preeclampsia o eclampsia, y la hemorragia posparto fue una complicación frecuente. La gran escasez de parteras, supervisión insuficiente y falta de habilidades propiciaron una prestación de atención inadecuada. El uso de prácticas basadas en evidencia que promuevan el parto normal es fundamental en lugares donde escasean los recursos y las mujeres tienen familias grandes. El informe de esta evaluación y las reuniones de difusión con prestadores de servicios, administradores de hospitales, formuladores de políticas y donantes fueron una revisión de la realidad para todas las partes implicadas, y se aprobó el plan de intervención para mejorar la calidad de la atención. Pese al clima continuo de crisis y los demás factores implícitos, las mujeres continúan dando a luz y desean recibir una atención amable y de calidad para ellas y sus recién nacidos. He aquí donde debe comenzar la oportunidad para realizar cambios.

Although childbirth in some developing countries has shifted from the home to the hospital, the institutionalisation of birth has not always been accompanied by improved practices or outcomes.Citation1 The components of effective childbirth care based on scientific evidence have been well documented and disseminated,Citation2Citation3 yet there seems to be a lag in the adoption of best practice both in developed and developing countries. Situating birth in its local environment contributes to understanding the complexity and diversity of childbirth care provision and what has shaped it.Citation4 A local needs assessment helps to understand what factors shape maternity care in a particular setting and what strategies might be most effective in adopting evidence-based best practices.

The purpose of this study was to assess the quality of maternity care in a large Palestinian referral hospital, as a first step in developing interventions to improve childbirth care for mothers and newborns. However, in order to understand the barriers to quality care, it is necessary to situate the birthing environment within the larger social, economic, and political context. The ongoing Israeli occupation of Palestine has contributed to a situation of fragmented, under-resourced and unregulated health services. The separation wall and over 500 checkpointsCitation5 in the Occupied Palestinian Territory limit access to maternity care and impede the effective organisation of and access to health care. Rising poverty, encompassing over 60% of the population,Citation6 is an additional barrier to accessing services in the private and non-governmental sector.

Most births (97%) take place in hospitals or clinics.Citation7 Since the Palestinian Ministry of Health took over responsibility from the Israeli Ministry of Defense for the health sector in 1994, it has encouraged all women to give birth in hospitals, phasing out community midwives and dayas (traditional birth attendants).Citation8 The 17 public hospitals in the West Bank and Gaza have become the place of birth for 56% of the 103,870 annual births,Citation9 primarily for the poor. However, the increasingly overcrowded and under-staffed maternity wards of public hospitals have compounded the risks for birthing women of unpredictable lack of access to maternity facilities and sub-optimal perinatal care. Whereas previously high-risk cases and complications from the West Bank were referred to the major Palestinian referral hospital in Jerusalem, with the restricted access to Jerusalem since 2000, most are now treated in the local public hospitals.

Due to a high total fertility rate of 4.6,Citation7 maternal and child health services comprise a large and critical portion of health service utilisation. Although antenatal care coverage is high (97%),Citation7 the overall quality is poor.Citation10 Intrapartum care in West Bank maternity facilities is frequently not based on scientific evidence,Citation11 in spite of the dissemination of national standards and guidelines. Few health care providers and ward managers were trained in how to instruct their staff in the use of these guidelines where many systemic and institutional obstacles impede implementation. The population-based caesarean delivery rate has doubled in the past decade from 6% in 1996 to 12.8% in 2004,Citation7 and the public hospitals’ caesarean rate reached 15.7% in 2004.Citation9 Women leave the hospital within 24 hours after a vaginal birth and three days after a caesarean section, and only one-third consult a maternal health provider during the six-week period thereafter.Citation7 Almost all Palestinian women breastfeed their babies (96%), although exclusive breastfeeding is not always practised, but a large majority (66%) continue to breastfeed at 9–12 months.Citation7

Our study setting was a general referral public hospital located in the middle governorate of the West Bank with 155 beds (including 36 maternity beds), treating about 20,000 in-patient and 70,000 emergency cases each year. It was one of the hospitals that had recently been made a major referral hospital to replace the one in Jerusalem. We chose this hospital because of its high delivery rate, serving primarily poor women in the area, unlike most maternity hospitals in the non-governmental and private sector. Approximately 4,000 births took place there annually, which was free of charge for those holding the public insurance instituted by the Ministry of Health for the poor during the second uprising in September 2000. Its proximity enabled the researcher to spend an extensive period of observation in the wards to better understand the childbirth environment. Since affecting change at the policy level is difficult in a weak and unregulated system, this assessment aimed to improve childbirth care through mid-level modifications targeting hospital-based midwives, the primary caregivers during normal birth, as the key agents of change.

Methodology

The objectives of this study were to assess the quality of maternity care in a large referral hospital, to identify the gaps and barriers to better practice, to provide baseline data for upgrading service provision, and to prepare a receptive context for change for the interventions to follow. International and local research was reviewed. Practices were assessed according to the latest scientific research on evidence-based obstetrics.Citation2Citation3 Two frameworks for the evaluation of quality of care guided the development of the instruments, which were adapted to local conditions: the WHO Safe Motherhood Needs Assessment ToolsCitation12 and the framework for quality of maternity services developed by Hulton et al.Citation13 The overall approach was influenced by the literature on the adoption of innovations in health care as a complex and adaptive process, which needs to take into account local structures, processes and patterns and which requires flexibility, creativity and interaction for translating research into practice.Citation14

In the hospital, quantitative and qualitative methods were used to assess technical and supportive care during delivery and the immediate post-partum period. Field observations, record reviews, case notes, exit interviews with women and in-depth interviews with providers and ward managers were collected between April 2005 and March 2006. The principal investigator (first author) is a Palestinian midwife with experience in running a busy maternity ward. She carried out most of the fieldwork, which aimed to eliminate one aspect of observer bias, as the staff became accustomed to her presence in the ward and were not intimidated (as might be the case if the observer were of a different nationality or profession), which was also conducive to the small budget allocated for this study. Before beginning the study, written and oral permission were obtained from the General Director of Hospitals at the Ministry of Health, the hospital director and the head obstetrician and midwife.

Observations were undertaken for 14 days (120 hours) during different days of the week and times of day (in the three shifts) in order to document actual practices and better understand childbirth management issues and interpersonal relations. Observations were the best way to understand the complexity of the birthing environment and create relationships of trust with the providers. In addition to direct observation in the wards, with prepared checklists as a guide, informal group discussions and one-to-one discussions with key informants (providers, managers and hospital administrators, women, clerks and cleaners) added to the richness and diversity of the information collected.

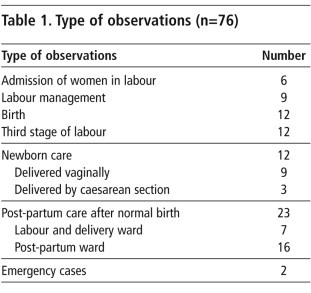

A total of 64 women and 12 newborns were observed using checklists, except for post-partum care and emergency events, where detailed notes were taken. Thirty-nine women were observed between the beginning of labour and the immediate post-partum period, 23 women during the post-partum period, two emergency cases, and 12 newborns (Table 1).

Ward registers and medical records were reviewed to collect data on ward statistics, actual practices and accuracy of record-keeping. Eleven medical records (nine normal births and two emergency events) were audited in detail using structured checklists.

Semi-structured interviews were conducted with all women who gave birth in the hospital (both normal and caesarean birth) during a two-week period by the researcher and one fieldworker (a midwifery teacher from outside the hospital trained for this purpose). After being informed of the purpose of the interview (the need to understand women’s views and how they were treated) and the identity of the interviewer (not a member of the hospital staff) and being assured of confidentiality, all of the women chose to participate. Due to the lack of a private place in the hospital to carry out interviews, 159 women were interviewed (either the day following birth or three days later for caesarean operations) individually by their beds, ensuring privacy as much as possible by closing the door, making sure that no providers were in the room at the time, and sitting close to the woman. The 15–30 minute interviews were in Arabic and focused on the choice of place of birth, the current birth experience, woman–provider interactions, and post-partum care. The cases were cross-checked with the birth register to make sure that no women had been overlooked.

Thirty-one in-depth interviews were carried out by the first author with all but one of the maternity care providers working in the hospital (9 midwives, 14 nurses and 8 physicians) using a semi-structured questionnaire with primarily open-ended questions. Each interview lasted 45–60 minutes, focusing on a description of their work and responsibilities, including childbirth practices and care, perceived barriers to quality care, training needs and suggested strategies for improvement.

SPSS Version 12 was used to analyse the quantitative data (closed-ended questions) from the interviews with women and providers. Observation checklists and record reviews were manually analysed by counting frequencies of various components of care.

Themes were initially identified through the women and providers interview guidelines. The researcher transcribed the content of the open-ended questions and categorised it according to the identified themes. Other concerns that emerged during the interviews were also included as themes. The content was analysed within the context of the overall birthing environment and the main findings of the study. Field observation notes were handwritten in the field and then typed and analysed the following day. In addition, the researcher had many informal discussions with the women, health providers, ward secretary and cleaners to clarify observations. Triangulation was utilised to verify the validity of qualitative findings from different sources. For example, case observations were compared with relevant records and with the informal discussions with women and providers. The data were further validated through discussions with providers during preliminary dissemination meetings.

Findings

Provider characteristics and responsibilities

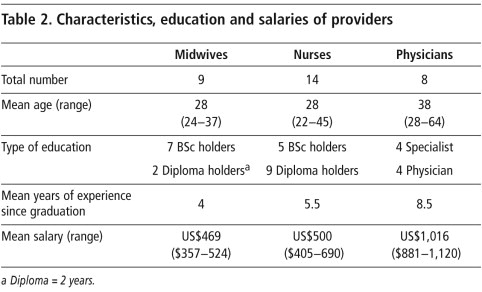

Of the 31 providers interviewed, midwives and nurses tended to be younger than physicians. The level of education of midwives was higher than of nurses (Table 2). Yet midwives had lower salaries than nurses, in spite of more years of study and experience, and greater responsibilities. Both physicians and midwives reported very high levels of stress. For midwives, this was due to difficult working conditions, low salaries, understaffing and lack of supportive supervision. For physicians and obstetricians, the stress was due to lack of experience with complicated cases. They reported that night shifts constituted a nightmare for them due to emergency “surprises”, for which they felt ill-prepared. As shown in Table 2, there was a rapid turnover of midwives, as most sought jobs elsewhere with less demanding and stressful working conditions. The insufficient staffing levels and long hours made it difficult for midwives to combine their work with their family roles and obligations.

Post-partum women interviewed

The 159 women interviewed had a mean age of 27 years. Half (51%) had nine years of schooling or less, 34% had 10–12 years and 15% had completed a degree. Twenty per cent were primiparae, and the other 80% had an average of 2.6 children (range 1–11). 25% had had a caesarean delivery and the rest normal vaginal births. 78% of women were living in rural areas; the rest were divided equally between urban areas and refugee camps. 62% had delivered previously in this hospital.

Delivery care

The hospital is a main clinical training site for midwifery, nursing and medical education programmes. During the study period, a range of 5–20 births with a mean of ten vaginal births (assisted by six midwives rotating in three shifts) and two caesarean sections were conducted over a 24-hour period. One physician staffed the labour ward on each shift and one obstetrician was on call; all of them were men. Midwives provided all the care for 91% of the vaginal births. Physicians were expected to prescribe medication, suture episiotomies and assist high-risk and caesarean deliveries. Epidurals for pain relief were not available and meperidine was used infrequently. Nurses provided post-partum care for women and newborns after normal and caesarean birth. Rooming-in and early initiation of breastfeeding had been adopted as hospital policy and routine supplemental liquids or formula were not used. The increasing caesarean section rate was due to the absence of an effective, early referral system for high risk cases to the hospital, unnecessary routine interventions during labour, the inadequate competence of physicians in making clinical judgements due to outdated knowledge, obstetricians who were stressed because of working in more than one institution and the declining health of pregnant Palestinian women.

Intra-partum care

There was severe understaffing of midwives, given their responsibilities and workload. Observation and women’s reports revealed that the mother frequently went through labour alone, with little caregiver support. At birth only one midwife was present. This resulted in unsafe birthing practices, involving either insufficient monitoring of the newborn or inappropriate care of the mother during the critical third stage of labour.

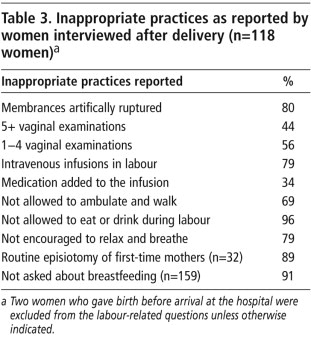

Infection control was insufficient and supplies frequently not available; women often gave birth without sheets on the beds, only plastic covers. Furthermore, observations and providers’ and women’s reports revealed the use of inappropriate practices (Table 3) such as restricting mobility and not allowing eating and drinking during labour, routine intravenous infusions with oxytocin during labour, no use of partograms, no family support person permitted, infrequent use of non-pharmacological methods of pain relief, no use of active management of the third stage of labour and routine episiotomy for first-time mothers. Women were observed asking for their newborns soon after birth to initiate breastfeeding, but the midwife had no time to assist them.

This pattern of care was consistent with providers’ reports. Frequent vaginal examinations were carried out, but not always documented in the records. Providers reported using oxytocin routinely to accelerate labour and midwives admitted administering it in the intravenous bags without using dropper machines to regulate dosage, due to lack of equipment, and frequently neglecting to put on a label.

When there was more than one birth at the same time, newborns were placed together under the only warmer in the delivery room, and sometimes no identification bracelets were put on the babies. One full-term newborn, left unattended, fell out of the warmer and had to be taken to intensive care. Another, born at 39 weeks, Apgar 8/9, and weighing 2kg had breathing difficulties. He was kept in the busy labour and delivery room for observation for more than five hours, and died unattended. Cases 1 and 2 that follow are representative of many of the cases we observed.

Case 1

At 9:30am, a 27-year-old woman, para 3, full term, was admitted to the hospital complaining of labour pains. A fetal heart monitor was placed for about ten minutes. Her case was straightforward without any significant history of complications in previous pregnancies. As part of the admission procedure, the physician conducted a vaginal exam and documented 6 cm dilation. The midwife repeated the vaginal exam, and the labouring woman was guided to the delivery room where she was placed in the lithotomy position on a delivery bed. An intravenous cannula was inserted and an infusion fluid was initiated. Two units of oxytocin were added to the infusion bag. However, no label was placed on the bag to show the additional medication. The bladder was emptied using a catheter. The woman was ready to deliver within 15 minutes. Although the main door of the room was partially closed, the woman without any sheet was exposed continually to the many staff and patients. The woman was assisted by the midwife in giving birth at 9:45am. Immediately after birth, the midwife placed a towel from the mother’s belongings on her abdomen for the baby and asked her to hold the baby while she cut the umbilical cord. The baby was then taken to the resuscitator in the next room, which was cold and not prepared for use. The baby was cleaned, suctioned and kept on a table near the warmer, not under it, as another premature baby was occupying the resuscitator. After checking the woman’s uterus, the midwife returned to the newborn, placed the cord clamp, weighed and dressed him. Then, without washing her hands, she continued to care for the other, premature baby. She returned to the mother for the delivery of the placenta, cleaned her and administered syntrometrine intra-muscular injection while the intravenous drip was still running. Blood pressure and fundal height were measured only once. The records were filled in by the other midwife on duty.

Case 2

A pre-term newborn, weighing 1800 gm was brought in to the labour and delivery ward by a physician from the operating theatre, after a caesarean section. Both midwives were busy and unavailable when the physician called for them, and no one answered him. He put the baby under the warmer and went to leave by the external, main door. I (first author) was observing in the main corridor and just could not remain silent. I asked him: “How come you left this newborn on the table without even checking if the warmer was on, or whether there was a midwife to provide care?” Without asking who I was, the physician went back and checked the warmer, which was cold. He turned it on, dried the newborn and gave her oxygen until one of the midwives took over about 20 minutes later. This reminded me of the comment of one of the physicians who used to work at this hospital:

“Those newborns certainly must have a guardian angel as it’s only God who takes care of them.”

Post-partum care

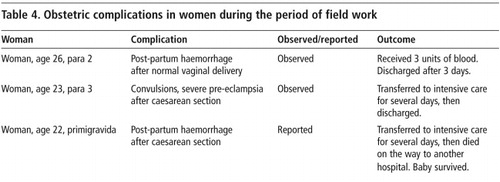

Many women did not receive adequate post-partum care. According to women’s reports, only 10% were asked about bleeding after vaginal birth, and only 13% had their lochia (discharge from the uterus during the puerperium) checked. These findings were consistent with nurses’ reports. More than half of post-partum women did not have their blood pressure taken, regardless of mode of delivery. Although half the nurses reported checking episiotomies, it was noted through observations that this was not done. Post-partum haemorrhage remained a frequent emergency, according to women and providers and the review of emergency cases. Magnesium sulfate, the drug of choice, was not used when pre-eclampsia or eclampsia occurred. Table 4 details the obstetric complications in women that were observed by the first author or what was “voluntarily reported” by midwives during the period of field work. We heard staff talking among themselves about other cases, but the records were incomplete and did not allow us to track them, and we decided not ask for details, as doing so might have been perceived as threatening.

The nurses’ knowledge of maternity care was very limited. None of the nurses reported providing any care or monitoring of newborns. Observation and women’s interviews indicated that women breastfed their babies in the post-partum period, but without any assistance from nurses or any health education.

Provider–patient relations

Although most women (87% with normal delivery and 90% with caesarean section) reported that their birth attendants were “nice” to them, only about half of them felt that the health care providers were friendly or polite. While 36% of women who considered their birth attendant to be “nice” reported that she was kind, patient, respectful and acceptable, 20% said she was nice only because she did not shout at them. Sometimes women were shouted at, sometimes considered ignorant and difficult to deal with, sometimes neglected and frequently not assisted, informed or consulted.

“Thank God, they did not shout at me” (Primigravida, 17 years old, 7 years education)

“The midwife frowned at me, was hot-tempered and shouted at me.” (Para 5, 25 years old, 8 years of education)

When women were asked if they were encouraged to ask questions, only 12% with a normal delivery and 18% with caesareans replied positively. Only 54% of the women said the midwife or nurse came quickly when they called for assistance. Nurses reported finding it difficult to deal with some of the women and their families who had a low level of education. Some women perceived that they were not all treated equally and that certain individuals with connections got special care. The women’s reports were consistent with the researcher’s observations and informal discussions with providers.

“The hospital is not clean at all. I am sleeping on a dirty sheet that has a bad smell. There are no curtains for privacy so that my husband can stay here without invading other women’s privacy. As you can see, I have no pillow and I am sleeping on my hand bag instead.” (Para 2, 24 years old, 8 years education)

“There are no sheets as you can see. I felt cold and asked the nurse to bring me a blanket; she did not and replied: ‘So what if you feel cold?’ I covered myself with my jelbab (long dress). I did not see any food here!” (Primigravida, 22 years old, third year university student)

Reasons for suboptimal care

Suboptimal care occurred because of a shortage of staff, as shown in the two cases above in which one midwife had to assist both in the birth and care of the newborn. Secondly, there was a lack of basic supplies and equipment due to an insufficient budget and/or dependence on international funds for items such as identification bands, linens, gauze and newborn warmers. Thirdly, there was poor management and organisation of care as shown in Case 2. Despite the presence of a specialised neonatal unit, newborns after caesarean sections were transferred to the busy understaffed labour and delivery ward to be observed and cared for. Fourthly, there was insufficient supervision, as the senior midwife divided the workload with the other midwife on duty, which left no time for supervision. Fifthly, as shown in the findings, there was outdated knowledge, particularly regarding management of the third stage of labour. Finally, staff felt powerless to effect change. For example, midwives reported that supervision was unsupportive and they felt powerless being at the bottom of the health system hierarchy, coping with unresponsive authorities.

Forbidding women to have female companions during labour and birth was a decision taken at the Ministerial policy level, but midwives and physicians agreed with this regulation as they considered family members an obstacle to efficient care. The issue of provider control of the labour process and environment was frequently reported by providers as the main reason for such inappropriate practices as limiting mobility during labour, restricting women to the lithotomy position to give birth, and the routine use of oxytocin to speed up labour and to free up beds for the next women coming in. Changing providers’ attitudes from controlling to assisting birthing women would therefore appear to be crucial.

Discussion

In this hospital the quality of basic childbirth care was inadequate and not consistent with best practice. While the results cannot be generalised to other maternity hospitals, communication with health providers and experience in the field indicate that many of the obstacles in other large institutions in the Occupied Palestinian Territory are similar. The results support findings from previous studies documenting the gap between evidence-based practices and routine care in PalestineCitation11, the Arab worldCitation15 and other regions of the world as well.Citation16Citation17 However, this study was able to validate providers’ reported practices through observation and exit interviews with women, to understand further the process of care. The research process stimulated health care providers to think, interact and initiate small changes in their own practice during the fieldwork. Moreover, it explored women’s views in a context where women were rarely consulted or included in medical decision-making.

The fact that the first author was a local midwife enabled her to build confidence among the midwives. While having one researcher doing all of the fieldwork might be considered a limitation, due to individual bias, it facilitated establishing contact and gaining insight into problem-solving in this neglected area of hospital services. Building trust, motivation and self-esteem in the maternity team helped to empower them to initiate change. The process of assessment was a way of preparing the ground to be receptive to change and to motivate the midwives to problem-solve. Field observation often poses the moral dilemma of observing harmful practices without intervening; instead, there is frequently a time lag between research findings and their translation into practice. We considered it ethically and strategically unjustifiable to observe evident malpractice without giving staff immediate feedback, as occurred in Case 2 above. Sometimes asking the right question was enough to initiate a process of change. Simple changes that evolved during the fieldwork were the utilisation of identification bands for the newborns and the acquisition of a second warmer for newborns in the delivery ward. More complex innovations, such as the use of the partogram, will require more staff and further on-the-job training and supervision.

Improving the safety of childbirth, motivating providers, reducing rapid staff turnover and meeting women’s needs involve systemic changes, including sufficient staff and ensuring enough midwives so that two are present at every birth – one for the mother and the other for the newborn.Citation18 The shortage of midwives is mainly due to systemic problems in human resource management, including in determining the required numbers of midwives for facilities and utilising the most appropriate types of providers. The lack of sufficient staff and supplies for the maternity services has been exacerbated by the recent international financial boycott of the elected Palestinian government; providers (particularly midwives) have had to ensure childbirth services for poor women under difficult circumstances and without receiving their salaries for more than ten months. Investing in midwives as providers of perinatal care during pregnancy, childbirth and the post-partum period has been shown to be effective and sustainable and to result in a lower caesarean section rate.Citation19 This would permit physicians, who expressed the need for more support and supervision, to focus on improving their skills.

Poverty and difficult access to maternity care facilities have increased the stress and severity of cases that providers have to deal with. For example, sometimes due to difficult access for women, physicians will induce or accelerate labour upon their admission to the labour ward. Having recently been made a referral hospital, this hospital needs to train and retain its existing physicians and attract new physicians who are highly skilled to cope with the heavy burden of high-risk cases, severe complications and surgical deliveries. This requires political commitment and awareness among decision-makers, and the translation of commitment into budgetary allocations and reform of the health system.Citation20 In the Palestinian case, effective internal reform must also be accompanied by the end of occupation as a prerequisite to respect for the basic human right of access to health care.

Caregiver and female relative support to promote normal labour and birth is essential, particularly in a culture that values family support.Citation21 Alternative methods of pain reliefCitation22Citation23 have been shown to be appreciated by women and to reduce interventions, and are particularly important in a context where epidurals are not available. Oxytocin was used routinely to speed up labour, in spite of the risks involved with its use in a situation where labour was not closely monitored.Citation24 The benefit of accelerating labour is in itself questionable, particularly where the normal duration of labour in a study in another Palestinian hospital was shown to be relatively short.Citation25 A rising trend in the caesarean section rate (particularly the primary rate) is a real concern for Palestinian women’s health, given the tendency to have large families.

Post-partum care for mothers and newborns was extremely inadequate. Globally, more than one half of all newborn deaths occur in the first 24 hours after birth and integrated maternal and newborn care is lifesaving.Citation26 Although exclusive breastfeeding for 4–6 months remains a challenge, the high initiation of breastfeeding in the hospital was most likely due to the culture of breastfeeding rather than specific hospital practices, as women received little support.

Like women all over the world, the Palestinian women interviewed wanted to be treated with respect, sensitivity and equality.Citation27 They were very enthusiastic about being interviewed and having the opportunity to express their opinions. As one woman said, she hoped that when she came back for her next birth, conditions would be better as she had no other place to give birth. Women were not always treated with empathy and respect, as the midwives themselves admitted. While such behaviour can be understood in relation to shortage of staff, low status, poor salaries and the inherent stress of obstetrics, the difficult relationship between women and hospital midwives and nurses is a multifaceted and universal problem. Poor working conditions are one cause, but lack of communication, a judgmental attitude and disregard for patients’ knowledge and concerns are all too frequent components of the provider–patient relationship, leading to dissatisfaction and lack of uptake of services.Citation28 Such attitudes need to be continually addressed with regard to the organisation of services, the accountability of providers and institutions, midwifery role models, and an emphasis not only on technical competence in maternity care, but also on interpersonal relations.

The publication of a detailed report of this assessment, along with several dissemination meetings with providers, ward and hospital managers, decision-makers at higher levels and donors succeeded in attracting attention to the poor conditions of normal childbirth and emergency obstetric care in the public sector. The assessment helped to raise awareness among managers and decision-makers of the need to allocate more financial support to this neglected area of women’s health care. Moreover, the intervention plan to improve the quality of care during childbirth in this hospital as a pilot project was approved and will hopefully be extended to other public hospitals in the future. Carrying out this assessment in an ongoing climate of crisis was a reality check for all involved, demonstrating that in spite of whatever may be going on in the wider world, women continue to give birth and to want kindness and good care for themselves and their newborns. And this is perhaps where the opportunity for change needs to begin.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the Theodor-Springmann Foundation for funding this study, Dr Rita Giacaman and Dr Rana Khatib for their continuous support and Sheila Narrainen for her assistance in editing earlier drafts of this paper. We are grateful to all the women, midwives and other providers who shared their experiences with us.

References

- S Miller, M Cordero, A Coleman. Quality of care in institutionalized deliveries: the paradox of the Dominican Republic. International Journal of Gynecology and Obstetrics. 82: 2003; 89–103.

- Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews Library. At <www3.interscience.wiley.com/cgi-bin/mrwhome/106568753/HOME>. Accessed 17 March 2007

- World Health Organization. WHO Reproductive Health Library. 2006; WHO: Geneva.

- S Wrede, C Benoit, I Bourgeault. Decentred comparative research: context sensitive analysis of maternal health care. Social Science and Medicine. 63: 2006; 2986–2997.

- UN News Service. Israeli obstacles to free movement in Palestinian territories mount. At: <www.un.org/apps/news/printnewsAr.asp?nid=20234>. Accessed 19 March 2007

- Palestinian Central Bureau of Statistics. Impact of the Israeli Measures on the Economic Conditions of Palestinian Households. 2006; PCBS: Ramallah.

- Palestinian Central Bureau of Statistics. Demographic and Health Survey 2004. Final Report. 2006; PCBS: Ramallah.

- R Giacaman, L Wick, H Abdul-Rahim. The politics of childbirth in the context of conflict: policies or de facto practices?. Health Policy. 72: 2005; 129–139.

- Ministry of Health. Health Status in Palestine: Annual Report 2004. 2005; MOH: Gaza.

- Maram Project. Baseline Assessment: Survey of Women and Child Health and Health Services in the West Bank and the Gaza Strip 2003. 2004; Maram Project: Ramallah.

- L Wick, N Mikki, R Giacaman. Childbirth in Palestine. International Journal of Gynecology and Obstetrics. 89: 2005; 174–178.

- World Health Organization. Safe Motherhood Needs Assessment Tools. 1996; WHO: GenevaAt: <www.who.int/reproductive-health/MNBH/smna_index.en.html>. Accessed 17 March 2007

- L Hulton, Z Matthews, R Stones. A Framework for Evaluation of Quality of Care in Maternity Services. 2000; University of Southampton: Southampton.

- P Plsek. Complexity and the Adoption of Innovation in Health Care. 2003; National Institute for Health Care Management Foundation: Washington DC.

- Choices and Challenges in Changing Childbirth Research Network. Routines in facility-based maternity care: evidence from the Arab world. BJOG: International Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology. 112: 2005; 1270–1276.

- JM Turan, A Bulut, H Nalbant. Challenges for the adoption of evidence-based maternity care in Turkey. Social Science and Medicine. 62(9): 2006; 2196–2204.

- P Garner, M Meremikwu, J Volmink. Putting evidence into practice: how middle and low income countries “get it together”. BMJ. 329(7473): 2004; 1036–1039.

- WHO/UNFPA/UNICEF/World Bank. Pregnancy, Childbirth, Postpartum and Newborn Care: A Guide for Essential Practice. 2003; WHO: Geneva.

- R Rosenblatt, SA Dobie, R Schneeweisser. Interspecialty differences in the obstetric care of low-risk women. American Journal of Public Health. 87: 1997; 344–351.

- World Health Organization. Quality of Care. A Process for Making Strategic Choices in Health Systems. 2006; WHO: Geneva.

- M Mosallem, D Rizq, L Thomas. Women’s attitudes towards psychosocial support in labour in United Arab Emirates. Archives of Gynaecology and Obstetrics. 269: 2004; 181–187.

- E Declercq, C Sakala, M Corry. Listening to Mothers: Report of the First National US Survey of Women’s Childbearing Experiences. 2002; Harris Interactive for the Maternity Center Association: NY.

- L Abushaikha. Methods of coping with labor pain used by Jordanian women. Journal of Transcultural Nursing. 18: 2007; 35–40.

- B Dujardin, M Boutsen, I De Schampheleire. Oxytocics in developing countries. International Journal of Gynecology and Obstetrics. 50: 1995; 243–251.

- N Mikki, L Wick, N Abu-Asab. Trial of amniotomy in a Palestinian hospital. Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 27(4): 2007; 368–373.

- E Sines, U Syed, S Wall. Postnatal Care: A Critical Opportunity to Save Mothers and Newborns. 2007; Population Reference Bureau: Washington.

- J Yelland, R Small, J Lumley. Support, sensitivity, satisfaction: Filipino, Turkish and Vietnamese women’s experiences of postnatal hospital stay. Midwifery. 14(3): 1998; 144–154.

- R Jewkes, N Abrahams, Z Mvo. Why do nurses abuse patients? Reflections from South African obstetric services. Social Science and Medicine. 47(11): 1998; 1781–1795.