Abstract

Western countries have reported an increased risk of maternal mortality among African immigrants. This study aimed to identify cases of maternal mortality among immigrants from the Horn of Africa living in Sweden using snowball sampling, and verify whether they had been classified as maternal deaths in the Cause of Death Registry. Three “locators” contacted immigrants from Somalia, Eritrea, and Ethiopia to identify possible cases of maternal mortality. Suspected deaths were scrutinised through verbal autopsy and medical records. Confirmed instances, linked by country of birth, were compared with Registry statistics. We identified seven possible maternal deaths of which four were confirmed in medical records, yet only one case had been classified as such in the Cause of Death Registry. At least two cases, a significant number, seemed to be misclassified. The challenges of both cultural and medical competence for European midwives and obstetricians caring for non-European immigrant mothers should be given more attention, and the chain of information regarding maternal deaths should be strengthened. We propose a practice similar to the British confidential enquiry into maternal deaths. In Sweden, snowball sampling was valuable for contacting immigrant communities for research on maternal mortality; by strengthening statistical validity, it can contribute to better maternal health policy in a multi-ethnic society.

Résumé

Les pays occidentaux ont déclaré une augmentation du risque de mortalité maternelle chez les immigrantes africaines. Cette étude souhaitait recenser les cas de mortalité maternelle chez les immigrantes de la Corne de l’Afrique vivant en Suède à partir d’un échantillon en « boule de neige », et vérifier s’ils avaient été classés comme tels dans le registre des causes de décès. Trois « enquêteurs » ont pris contact avec des immigrants éthiopiens, érythréens et somaliens pour identifier les cas possibles de mortalité maternelle. Les décès suspects ont été examinés par autopsie verbale et avec les dossiers médicaux. Les cas confirmés, ventilés par pays de naissance, ont été comparés avec les statistiques de l’état civil. Nous avons identifié sept décès maternels possibles dont quatre avaient été confirmés dans les dossiers médicaux. Pourtant, un seul figurait comme tel dans le registre des causes de décès. Au moins deux cas, soit un nombre non négligeable, semblaient avoir été mal classés. Il faut s’intéresser davantage aux compétences médicales et culturelles des sages-femmes et des obstétriciens européens qui soignent les mères immigrantes non européennes et renforcer la chaîne d’informations sur les décès maternels. Nous proposons une pratique similaire à l’enquête confidentielle britannique sur les décès maternels. En Suède, l’échantillonnage en boule de neige a permis de contacter des communautés immigrantes pour faire des recherches sur la mortalité maternelle ; en renforçant la qualité des statistiques, il peut améliorer la politique de santé maternelle dans une société pluriethnique.

Resumen

Los países occidentales han informado un mayor riesgo de mortalidad materna entre los inmigrantes africanas. El objetivo de este estudio fue identificar los casos de mortalidad materna entre inmigrantes del Cuerno de Ãfrica que vivían en Suecia, utilizando el muestreo de bola de nieve, y verificar si habían sido clasificadas como muertes maternas en el Registro de Causa de Defunción. Tres “localizadores” contactaron inmigrantes de Somalia, Eritrea y Etiopía para determinar los casos posibles de mortalidad materna. Las muertes sospechadas fueron examinadas mediante autopsia verbal e historiales médicos. Los casos confirmados, vinculados por país de nacimiento, fueron comparados con las estadísticas del Registro. Identificamos siete posibles muertes maternas, de las cuales cuatro fueron confirmadas en los historiales médicos, pero sólo un caso había sido clasificado como tal en el Registro de Causa de Defunción. Por lo menos dos casos, un número significante, parecieron ser mal clasificados. Se debe prestar más atención a los retos de competencia cultural y médica afrontados por parteras y obstetras europeos que atienden a madres inmigrantes no europeas, y se debe fortalecer la cadena de información sobre las muertes maternas. Proponemos una práctica similar a la investigación confidencial británica de muertes maternas. En Suecia, el muestreo de bola de nieve fue valioso para contactar comunidades inmigrantes para investigaciones sobre la mortalidad materna; el fortalecer la validez estadística puede contribuir a mejorar la política de salud materna en una sociedad multiétnica.

Under-reporting of maternal mortality in low-income countries is a problem attributable mainly to non-existent registers and misclassification.Citation1Citation2 However, even in high-income countries with low maternal mortality ratios, under-reporting and misclassification can occur, and regular reviews of maternal mortality are considered important.Citation3Citation4

Maternal mortality is the death of a woman during pregnancy or the puerperium within 42 days of delivery from any cause related to or aggravated by pregnancy. In the early 1990s the definition in the International Classification of Diseases 9 (ICD-9) was expanded by the World Health Organization to include deaths occurring up to one year from the end of pregnancy (late maternal deaths) and deaths from any cause during the puerperium (pregnancy-related maternal death).Citation5 Late maternal death was added in order to include women who lived beyond 42 days, e.g. due to modern life-sustaining techniques. Pregnancy-related mortality was added to encompass women who died outside medical facilities and for whom the exact cause of death could not be established. Deaths from unrelated causes which happen to occur in pregnancy or the puerperium were classified as “incidental” instead of “fortuitous”.Citation6 The current ICD-10 definitions were introduced in Sweden in 1997.

Sweden has one of the lowest maternal death ratios in the world, from 2–6 deaths per 100,000 live births, according to the Cause of Death Registry, which includes all certified deaths in Sweden. The cause of death is associated with a unique personal identification number assigned to every legal resident of Sweden by the Medical Birth Registry, which contains pregnancy-related data as well as maternal country of birth. The Cause of Death Registry focuses on ICD-9 and ICD-10 codes related only to pregnancy from direct or indirect causes within 42 days of the end of pregnancy.

Western countries have reported an increased risk of maternal and perinatal mortality among African immigrants, compared to native-born residents.Citation7–11 A recent confidential enquiry into maternal deaths in the UK studied deaths among disadvantaged women, including black African women, and found they were more likely to die during pregnancy, childbirth or the puerperium than their white counterparts.Citation12 To our knowledge, there is a lack of similar studies of maternal mortality and ethnicity in Sweden.

The aim of this study was to identify cases of maternal mortality among immigrants from the Horn of Africa living in Sweden, using snowball sampling, and verify whether any such case identified had been classified as a maternal death in the Cause of Death Registry.

Methodology

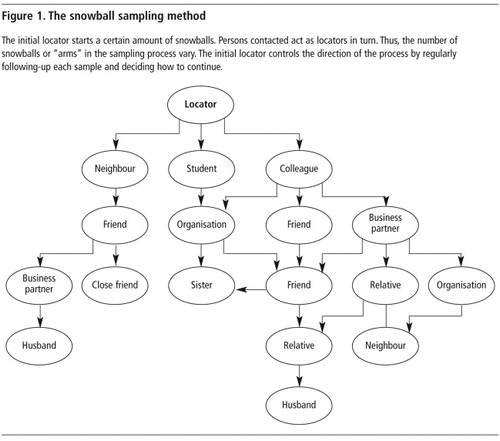

Snowball sampling was used to identify probable maternal deaths during 2003 to 2006. This method, also referred to as networking, yields a study sample through referrals made by people who either know of a case themselves or know of others who do. The challenge is to find respondents and start referral chains, verify the eligibility of potential respondents, employ people who are familiar with the study population to serve as “locators” (who serve as initial contacts with informants), control the types of chains and number of cases in any chain, and pace and monitor referral chains and data quality ().Citation13

In this study, three locators (one of Somali origin, one Eritrean, and one Ethiopian (author KM)) and two Swedish researchers (authors KE and BE) monitored the snowball process. The locator for the Somali immigrant group used her contacts within the Somali community and immigrant organisations to initiate various snowball samples. The study was publicised on Somali radio and TV programmes in Sweden. The Somali locator ultimately contacted people in at least eight Swedish cities. Similarly, the locators for Ethiopian and Eritrean groups started snowball samples through organisations, acquaintances and friends, as well as in open meetings in East African communities in Stockholm, Gothenburg and Malmö, the three largest cities in Sweden. The locators were experienced in interviewing women about sensitive topics, such as female genital cutting. The Eritrean locator contacted approximately 100 people in person, mostly from Eritrea, but some from Ethiopia; the Ethiopian locator contacted 35 families of Ethiopian origin in three different cities.

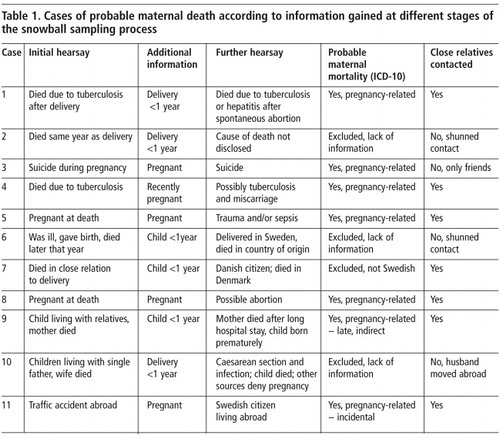

Each locator began by asking if someone had heard of a woman of childbearing age (15–49 years) who had died in Sweden (Table 1, initial hearsay). When the answer was “yes” the next step was to find out if the woman had been pregnant within one year of her death (Table 1, additional information). If so, the cause of death was sought and near relatives were tracked (Table 1, further hearsay). Locators, friends and families played a crucial role in contacting relatives of the deceased, informing them of the project and introducing them to the research team ().

Verbal autopsies (in-depth interviews with semi-structured questions regarding the circumstances surrounding the death) were carried out with relatives in 2004–2005 in order to verify that these were actually maternal deaths.Citation14 Informants were chosen on the basis of close kinship with the deceased and their attendance during her confinement. The Somali informants interviewed consisted in one case of a sister and in three others of husbands. All were born in Somalia; one spoke no Swedish necessitating the use of a professional interpreter. All interviews were conducted by a Swedish and a Somali researcher working in tandem and lasted one to two hours. Two of the interviews were tape-recorded and transcribed verbatim. Since two other informants did not wish to be tape-recorded, case notes were taken instead. Three Swedish members of the research team analysed the texts of the interviews independently, scrutinising the circumstances surrounding the women’s deaths. After obtaining consent from the family, medical records of the diseased were examined and compared with the information gathered from relatives. In order to find out if cases were classified as maternal deaths in the Cause of Death Registry, we contacted Statistics Sweden. The number of all deceased women from the Horn of Africa and year of death were obtained, including all maternal deaths.

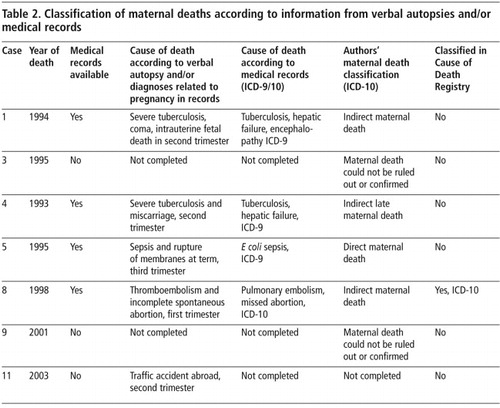

In the first step of snowball sampling, all ICD-10 definitions (all pregnancy-related, late and incidental deaths) were used when classifying cases of probable maternal deaths (Table 1). Our classifications were based on information from verbal autopsies and patients’ medical records (Table 2). Finally, we wanted to know if our cases were classified as maternal death in the register (presented in Table 2 as yes/no). Through linking country of birth data, snowball sample cases could be compared with classified cases of maternal death in the Cause of Death Registry (direct and indirect pregnancy-related deaths within 42 days).

Information concerning the study’s purpose, confidentiality and the de-identification of cases were given in Swedish and, as needed, in the informant’s native language. All interviews were conducted only after receiving informed consent. We present general classificatory information regarding maternal mortality for each case. Details concerning background factors have been omitted to ensure confidentiality. The study was approved by the Ethics Research Committee of Lund University, Sweden (LU954-03).

Findings

Probable cases of maternal deaths

In total, 18 cases of women of reproductive age who had died were identified initially. All cases were found among the Somali immigrants in our study. One woman in the Ethiopian group died of cancer unrelated to pregnancy or childbirth. Seven Somali cases were eliminated from further consideration because we could not confirm by means of interviews whether the women had been pregnant during the year preceding their deaths. The remaining 11 cases of possible maternal deaths were pursued further, as illustrated in Table 1. According to the information given by various sources during the process of snowball sampling, it appeared that seven of the 11 cases were instances of maternal death. Based on snowball sampling data and according to ICD-10, we classified them as six pregnancy-related deaths, irrespective of the cause of death (cases 1, 3, 4, 5, 8, 11), and one late maternal death (case 9). The other four cases were excluded (Table 1). Of the latter, three could neither be ruled out nor confirmed as maternal deaths due to lack of information (cases 2, 6, 10). Case 7 was a probable maternal death, but was excluded because she was Danish.

In six of the seven cases of probable maternal death (cases 1, 4, 5, 8, 9, 11) (Table 1), we were able to determine the names of relatives and contacted five of them. It was considered inappropriate to contact relatives in one case because of the family situation we were apprised of. Relatives of the deceased agreed to be interviewed in cases 1, 4, 5, 8 (Table 2). Two relatives chose not to be interviewed because they said the stress of talking about their loss would be too great.

By conducting interviews using verbal autopsy techniques with surviving relatives, four out of seven cases of potential maternal deaths were confirmed to a very high degree of probability as cases of maternal mortality (Table 2). Information obtained from medical records supported the preliminary classifications made on the basis of interviews. The causes of death stated by the informants and in the medical records, as interpreted by our researchers, yielded the following ICD-10 classifications: three indirect maternal deaths (one of them late), and one direct maternal death.

The second aim of the study was to verify whether the cases were classified in the Cause of Death Registry as maternal deaths. Using country of birth gave the possibility to link snowball data to Registry data. Between 1968 and 2003 there were, in all, 178 women from the Horn of Africa recorded in the Swedish Cause of Death Registry. Of these, only one Ethiopian woman (in 1991, not located in our study) and one Somali woman in 1998, (Case 3, Table 2) were classified as maternal deaths according to ICD-10 (Personal correspondence, F Lundgren, Swedish Board of Health and Welfare, 2005).

Case 3 had no medical record linked to the Medical Birth Registry, due to death in early pregnancy; however, a pregnancy-related ICD code in the death certificate was identified. Among the other cases, diagnoses related to pregnancy were identified in patient medical records, but were not classified as such in the Cause of Death Registry. Cases 1 and 5 seemed to have been misclassified, but the late death case 4 was not supposed to be classified as a maternal death in the Swedish context.

History of maternal deaths

Background information concerning the four deceased women is based on interviews with relatives and confirmed by clinical records ( 1 ). The deaths cited above occurred between 1993 and 2001 in various hospitals in Sweden. All four women were born in Somalia but had held Swedish citizenship for several years. Their total childbirth experience ranged from one to nine deliveries. Two women had given birth in both Somalia and Sweden; two had given birth only in Sweden. All four women had previously experienced at least one uncomplicated delivery in Sweden. With the exception of one woman who had had a severe bout of tuberculosis, indications were that the women were previously healthy.

Discussion

Seven cases with a great likelihood of being maternal deaths among Somali women in Sweden were identified by snowball sampling and confirmed by verbal autopsies. Four cases were classified as maternal deaths (one direct, two indirect and one indirect late) based on data from medical records and reconfirmed by using the information from snowball sampling. According to Swedish statistics, only two cases of maternal deaths had occurred in all among 178 deceased women from the Horn of Africa during the study period. One instance was a case we also identified, but there were at least two more cases defined according to ICD codes related to pregnancy that seemed to be misclassified.

Snowball sampling has its limitations. Analysis of the Cause of Death Registry as to whether cases were registered at all, and if so, the underlying ICD causes of death, were not achievable using the method. However, we found that three Somali women with diagnoses related to pregnancy in their medical records were not classified as maternal deaths. Two of these three cases (Cases 1 and 5) were identified as direct and indirect maternal deaths, respectively, according to the Swedish classification.

The study design did not include a proper audit procedure of each case but identified information worth considering when studying maternal morbidity in a multi-ethnic society. Tuberculosis and hepatic failure (Cases 1 and 4) are potential causes of deaths that European doctors are not trained to recognise, raising the issues of suboptimal care and miscommunication.Citation11 In Sweden, deaths in pregnancy related to tuberculosis have not occurred for the last 50 years. The embolism-related death (Case 8) was mentioned in a recent study of maternal death and pulmonary embolism: “Two women were immigrants from sub-Saharan Africa; there was a delay in seeking health care in one case, and verbal miscommunication might have contributed in both cases.”Citation15 The challenges of both cultural and medical competence for European midwives and obstetricians caring for non-European immigrant mothers should be given more attention. We suggest the introduction of routine maternal and perinatal death auditsCitation12 in Sweden, as a way to explore maternal mortality from a migrant perspective.

We were unable to find any cases of probable maternal death among Ethiopian and Eritrean women, whereas we located seven cases among Somali women. This could either be a true difference or a sampling bias. In 2003, 14,808 persons born in Somalia, 11,281 born in Ethiopia, and 4,353 born in Eritrea resided in Sweden, according to government statistics. However, Eritrean and Ethiopian immigrants arrived in Sweden a few decades earlier than Somali immigrants, and are thus more integrated into Swedish society.Citation16 In a small immigrant population of 15,000 people, the interviewers located 11 cases interpreted as relating to pregnancy. Qualitative data from this study should not be used for quantitative calculations. However, the notion increases the perceived risk in relation to childbirth in this community. Ten deaths perceived as maternal deaths per 3,000–5,000 live births are more likely to happen in a high mortality setting where childbirth can be a deadly threat. This also holds true with the final figure of four cases. Our findings are supported by epidemiological studies in Europe and the USA showing a pattern of poor obstetric outcomes among Somali refugees in the West.Citation10,17–19

We estimate that our Somali locator initiated more “snowballs” than the other locators, and actively performed the snowball sampling for a longer period of time than the others. The over-representation of Somali cases might also have been a result of differences in the Somali network size. Further, unlike Ethiopian and Eritrean communities, Somali communities in Sweden are linked by strong networks, which may have resulted in more recruitment paths.Citation20Citation21

The snowball method involves strategic sampling, as opposed to the randomised approach commonly used in epidemiological studies.Citation22 In studying uncommon, controversial or sensitive phenomena otherwise inaccessible to research, such as the non-reported cases of maternal deaths in this study, the snowball approach shows great promise.Citation23 Certainly, there may be other missing cases of maternal deaths not possible to identify by the method used in this study. These might be found through quantitative studies in registers of fetal death, abortion and hospital discharge registers.

Snowball sampling is often employed in the social sciences. Although its use in medical studies is less common, it has nevertheless been applied in a variety of settings.Citation24–26 The tragic death of a woman and mother can be expected to remain a socially significant event in the consciousness of a close-knit community. This was an important prerequisite for the choice of method in our study. However, an obvious disadvantage is the difficulty of controlling the pace and direction of the sampling process, i.e. the number of locators to use and when to speed up or slow down the process in order to amass reliable data. In this study, our aim was to achieve the broadest possible coverage of probable maternal deaths, though using multiple locators for each immigrant group might have resulted in more cases. However, even in our limited study, snowball sampling facilitated contacting immigrants with knowledge of potential maternal deaths in Sweden.

Respondent-driven sampling is a method of enhancing statistical validity. shows how 11 “snowballs” initiated a process that ultimately resulted in the identification of seven probable ICD10-defined, pregnancy-related deaths. By using locators who acted as cultural brokers, sources were contacted who otherwise might have remained unidentified.

Accurately determining a cause of death and classifying maternal mortality is generally regarded as difficult in community-based verbal autopsies.Citation23 In order to decrease the risk of false positive classification and increase validity, triangulation of the information was used: data concerning each case were collected from several persons independently of one another. In addition, information was verified through clinical records wherever possible. If there was any doubt whether cases were maternal deaths, those cases were excluded (Table 1). Moreover, the seven cases of probable maternal deaths identified without the benefit of verbal autopsies or review of medical records are presented only as possible pregnancy-related maternal deaths.

In some cases spontaneous abortion was part of the subject’s history. Some under-reporting of maternal deaths in early pregnancy in Sweden might stem from unawareness on the part of clinicians and officials that early termination of pregnancy, whether spontaneous or induced, may have been noted in the Cause of Death Registry, while cases of second trimester pregnancy may not have been registered in the Medical Birth Registry, e.g. in Case 1. A study from the Netherlands confirms that early pregnancy deaths and indirect deaths stand a high risk of being under-reported, as the fact that the deceased had been pregnant, though noted on the death certificate, was commonly overlooked.Citation10 In our study, the correctly classified Case 8 was related to first trimester abortion.

The Cause of Death Registry includes information obtained from certificates collected by local parish registries. As a national register, it includes the deaths of all persons whose identity is registered in Sweden at the time of their death, including those whose deaths occurred outside Sweden. The register is updated yearly and lists the individual’s personal identification number, city of birth, underlying cause of death, nature of injury, multiple causes of death, date of death, basis for determining cause of death, sex and age. In 1994, the rates of all non-reported deaths was 0.45%.Citation27 To our knowledge, a similar rate of non-reported or misclassified maternal deaths in the Cause of Death Registry has not previously been reported in Sweden.

The Swedish Medical Birth Registry, which links pregnancy-related data to the Cause of Death Registry, is known as a valuable source of information for reproductive epidemiology. Records for only a very small percentage of all those registered in Sweden (0.5–3.9%) are missing completely.Citation28 Surprisingly, one case occurred at term of pregnancy and should have been in the Medical Birth Registry but was not correctly classified (Case 5, Table 2). If a maternal death occurs while a woman is in an intensive care unit, for example, the pregnancy may not be noted in the report of death certificate to the Cause of Death Registry, in which each death is classified by an ICD code.Citation29

The quality of the statistics varies, depending on the nature of the examination made to determine the underlying cause of death. The most exhaustive way to establish a cause of death is by clinical or forensic autopsy, performed on the initiative of a doctor or ordered by the police, respectively. A general decrease in the number autopsies performed might lead to inaccurate statistics. Reasons for such a decrease might include changing financial compensation rates for clinical autopsies and changes in police directives for ordering forensic autopsies. The maternal deaths identified in our study may also not have found their way into official maternal mortality statistics because of the right of relatives to decline autopsies for cultural or religious reasons.

Sweden has one of the lowest maternal mortality rates in the world. Swedish statistics on causes of death are among the oldest instances of such record-keeping in modern times: an almost universal vital registration system tracks births and deaths for the country’s entire population. The misclassified cases of maternal deaths we identified by snowball sampling should be viewed in the light of an ongoing discussion of certain inaccuracies in the Swedish measurement of maternal mortality. ICD-10 has widened the concept of maternal mortality in order to gather global statistics that more closely correspond to reality. Using ICD-10 in full might be helpful in contemporary Europe with its growing population from low-income countries with high levels of maternal mortality. It is uncertain to what extend physicians in Sweden and elsewhere are familiar with the scope of the ICD – regardless which version is used.

Increasing awareness of the risk of misclassification and improvements in the quality of maternal mortality registration are important if international maternal mortality statistics are to be made reliable and comparable, and if care is to be improved. We propose for Sweden a practice similar to the confidential enquiries into maternal and perinatal deaths in the British system.Citation12 Confidential enquiries include demographic surveillance as well as case reviews. A multidisciplinary panel of practising clinicians with a wide variety of experience would participate. By including anthropological expertise, this procedure would increase our understanding of patterns of maternal death among different ethnic groups in Sweden and might be a good way of identifying cases in early pregnancy, indirect and late cases as well as others.

The number of misclassified maternal deaths we uncovered was significant. The new challenges of both cultural and medical competence for European midwives and obstetricians caring for non-European immigrant mothers should be given more attention, and the whole chain of information regarding maternal mortality should be strengthened. In Sweden, non-randomised snowball sampling has proven its value in contacting immigrants in communities from the Horn of Africa for medical research on maternal mortality. By strengthening statistical validity, it can contribute to better maternal health policy in a multi-ethnic society.

Acknowledgements

We would like to express our appreciation to the locators in this study for their hard work in obtaining data, and to all the participants from the Horn of Africa in communities throughout Sweden for their cooperation and generosity. We also thank Dr Jerker Liljestrand, Lund University, for his assistance with study design. Our research was supported by the Faculty of Medicine, Lund University, Sweden.

References

- L Hoj, J Stensballe, P Aaby. Maternal mortality in Guinea-Bissau: the use of verbal autopsy in a multi-ethnic population. International Journal of Epidemiology. 28(1): 1999; 70–76.

- A Mungra, RW van Kanten, HH Kanhai. Nationwide maternal mortality in Surinam. British Journal of Obstetrics & Gynaecology. 106(1): 1999; 55–59.

- C Deneux-Tharaux, C Berg, MH Bouvier-Colle. Underreporting of pregnancy-related mortality in the United States and Europe. Obstetrics & Gynecology. 106(4): 2005; 684–692.

- U Högberg, E Innala, A Sandström. Maternal mortality in Sweden, 1980–1988. Obstetrics & Gynecology. 84(2): 1994; 240–244.

- JA Fortney. Implications of the ICD-10 definitions related to death in pregnancy, childbirth or the puerperium. World Health Statistics Quarterly. 43(4): 1990; 246–248.

- World Health Organization. Maternal mortality in 2000: estimates developed by WHO, UNICEF and UNFPA. 2004; WHO: Geneva.

- JM Ibison, AJ Swerdlow, JA Head. Maternal mortality in England and Wales 1970–1985: an analysis by country of birth. British Journal of Obstetrics & Gynaecology. 103(10): 1996; 973–980.

- HK Atrash, LM Koonin, HW Lawson. Maternal mortality in the United States, 1979–1986. Obstetrics & Gynecology. 76(6): 1990; 1055–1060.

- CJ Berg, J Chang, WM Callaghan. Pregnancy-related mortality in the United States, 1991–1997. Obstetrics & Gynecology. 101(2): 2003; 289–296.

- N Schuitemaker, J van Roosmalen, G Dekker. Confidential enquiry into maternal deaths in the Netherlands 1983–1992. European Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology and Reproductive Biology. 79(1): 1998; 57–62.

- B Essén, B Bodker, NO Sjoberg. Are some perinatal deaths in immigrant groups linked to suboptimal perinatal care services?. British Journal of Obstetrics & Gynaecology. 109(6): 2002; 677–682.

- CEMACH. Why Mothers Die 2000–2002. 2004; Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists: London.

- P Biernacki, D Waldorf. Snowball sampling - problems and techniques of chain referral sampling. Sociological Methods & Research. 10: 1981; 141–163.

- NL Sloan, A Langer, B Hernandez. The aetiology of maternal mortality in developing countries: what do verbal autopsies tell us?. Bulletin of World Health Organization. 79(9): 2001; 805–810.

- E Samuelsson, M Hellgren, U Högberg. Pregnancy-related deaths due to pulmonary embolism in Sweden. Acta Obstetricia et Gynecologica Scandinavica. 86(4): 2007; 435–443.

- S Johnsdotter, R Aregai, A Carlbom. [“Never my daughters” – a qualitative study regarding attitude change towards female genital cutting among Ethiopean and Eritrean families in Sweden, 2003–2004]. 2005; Radda Barnen Sweden: Stockholm[In Swedish]

- B Essén, BS Hanson, PO Ostergren. Increased perinatal mortality among sub-Saharan immigrants in a city-population in Sweden. Acta Obstetetricia et Gynecologica Scandinavica. 79(9): 2000; 737–743.

- S Vangen, C Stoltenberg, RE Johansen. Perinatal complications among ethnic Somalis in Norway. Acta Obstetricia et Gynecologica Scandinavica. 81(4): 2002; 317–322.

- EB Johnson, SD Reed, J Hitti. Increased risk of adverse pregnancy outcome among Somali immigrants in Washington state. American Journal of Obstetrics & Gynecology. 193(2): 2005; 475–482.

- S Johnsdotter. Created by God: how Somalis in Swedish exile reassess the practice of female circumcision. 2002; PhD, Lund University: Toronto.

- K Bailey. Methods of social research. 1994; Free Press, Maxwell Macmillan Canada: Toronto.

- R Magnani, K Sabin, T Saidel. Review of sampling hard-to-reach and hidden populations for HIV surveillance. AIDS. 19(Suppl 2): 2005; S67–S72.

- C Ronsmans, AM Vanneste, J Chakraborty. A comparison of three verbal autopsy methods to ascertain levels and causes of maternal deaths in Matlab, Bangladesh. International Journal of Epidemiology. 27(4): 1998; 660–666.

- JT Boerma, JK Mati. Identifying maternal mortality through networking: results from coastal Kenya. Studies in Family Planning. 20(5): 1989; 245–253.

- S Clark, J Blum, K Blanchard. Misoprostol use in obstetrics and gynecology in Brazil, Jamaica, and the United States. International Journal of Gynecology and Obstetrics. 76(1): 2002; 65–74.

- S Jirojwong, R MacLennan. Health beliefs, perceived self-efficacy, and breast self-examination among Thai migrants in Brisbane. Journal of Advanced Nursing. 41(3): 2003; 241–249.

- National Board of Health and Welfare Centre of Epidemiology. The Swedish Medical Birth Registry – A Summary of Content and Quality. At: <www.sos.se/fulltext/112/2003-112-3/2003-112-3.pdf>. Accessed March 2007

- S Cnattingius, A Ericson, J Gunnarskog. A quality study of medical birth registry. Scandinavian Journal of Social Medicine. 18(2): 1990; 143–148.

- U Högberg. Maternal deaths in Sweden, 1971–1980. Acta Obstetricia et Gynecologica Scandinavica. 65(2): 1986; 161–167.